Published online Feb 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.98447

Revised: November 6, 2024

Accepted: December 26, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2025

Processing time: 111 Days and 1.6 Hours

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) frequently expe

To construct and validate a GAD risk prediction model to aid healthcare professionals in preventing the onset of GAD.

This retrospective analysis encompassed patients with COPD treated at our institution from July 2021 to February 2024. The patients were categorized into a modeling (MO) group and a validation (VA) group in a 7:3 ratio on the basis of the occurrence of GAD. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were utilized to construct the risk prediction model, which was visualized using forest plots. The model’s performance was evaluated using Hosmer-Lemeshow (H-L) goodness-of-fit test and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

A total of 271 subjects were included, with 190 in the MO group and 81 in the VA group. GAD was identified in 67 patients with COPD, resulting in a prevalence rate of 24.72% (67/271), with 49 cases (18.08%) in the MO group and 18 cases (22.22%) in the VA group. Significant differences were observed between patients with and without GAD in terms of educational level, average household income, smoking history, smoking index, number of exacerbations in the past year, cardiovascular comorbidities, disease knowledge, and personality traits (P < 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that lower education levels, household income < 3000 China yuan, smoking history, smoking index ≥ 400 cigarettes/year, ≥ two exacerbations in the past year, cardiovascular comorbidities, complete lack of disease information, and introverted personality were significant risk factors for GAD in the MO group (P < 0.05). ROC analysis indicated that the area under the curve for predicting GAD in the MO and VA groups was 0.978 and 0.960. The H-L test yielded χ2 values of 6.511 and 5.179, with P = 0.275 and 0.274. Calibration curves demonstrated good agreement between predicted and actual GAD occurrence risks.

The developed predictive model includes eight independent risk factors: Educational level, household income, smoking history, smoking index, number of exacerbations in the past year, presence of cardiovascular comor

Core Tip: This study constructs and validates a predictive model for generalized anxiety disorder in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Utilizing a retrospective design, we identified eight independent risk factors, including educational level, household income, smoking history, smoking index, number of exacerbations, cardiovascular com

- Citation: Zhao YP, Liu WH, Zhang QC. Determinants of generalized anxiety and construction of a predictive model in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(2): 98447

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i2/98447.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.98447

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressively developing chronic lung condition characterized by respiratory symptoms and irreversible airflow limitation[1]. Epidemiological studies indicate[2] that the prevalence of COPD in China stands at 8.6%, increasing to 13.7% among individuals over the age of 40 years and affecting nearly 100 million people’s health. The incidence and mortality rates of COPD have been increasing annually, and it is projected to become one of the leading causes of death globally by 2030, thus representing a remarkable public health challenge in China. Research has demonstrated[3,4] that patients with COPD frequently present with various extrapulmonary diseases, such as cardiovascular alterations, metabolic syndrome, lung cancer, and anxiety, all of which exacerbate the severity of the disease, diminish quality of life, and serve as independent risk factors for hospitalization and mortality.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a prevalent psychiatric condition marked by non-specific or unfixed anxiety objects, accompanied by restlessness. Its core features include uncontrollable chronic worry and a cognitive bias towards perceiving threats and risks, effecting interpersonal relations, work capacity, and overall physical and mental health[5]. Due to recurrent exacerbations requiring multiple hospitalizations and a prolonged disease course, patients with COPD experience progressively worsening clinical symptoms, which affect their daily functioning and social activities, leading to economic and familial burdens and increased psychological distress, thus making them prone to developing anxiety. Anxiety, in turn, exacerbates health issues, such as breathing difficulties, mobility impairments, and social isolation, thereby creating a vicious cycle[6]. Previous studies have noted[7] that patients with COPD with concurrent GAD exhibit more acute symptoms and reduced exercise tolerance. Hence, early screening and intervention for GAD can significantly improve their quality of life.

Past research predominantly utilized the GAD 7-item scale (GAD-7) for screening although GAD-7 primarily relies on self-reported data from patients, which may be subjective and influenced by personal perceptions[8]. Logistic regression analysis is a statistical method that integrates the study of independent disease risk factors to establish predictive models, quantifying the contributions of covariates and realizing the synergistic effects of multiple variables[9]. The current literature on predictive models for GAD risk among patients with COPD is limited. The present study primarily analyzed COPD patient data retrospectively, identified risk factors for GAD, constructed a GAD risk prediction model, and validated its utility to assist healthcare professionals in preventing the onset of GAD and enhancing the emotional well-being and quality of life of patients with COPD.

This retrospective study included patients with COPD treated at our institution from July 2021 to February 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Confirmed diagnosis of COPD, age > 18 years, complete GAD-7 clinical data available, and coherent and able to communicate verbally or in writing. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Concurrent malignancies, tuberculosis, or other diseases; liver or kidney dysfunction; and alcohol or psychotropic drug dependency. The sample size was calculated using the following formula: N = Z² [π (1 - π)]/δ², where Z = 1.96 at an alpha level of 0.05, δ is the allowable error, and π = 0.17, based on the documented incidence of GAD in patients with COPD being 17.0%[10], with an allowable error of 5%. This calculation indicated a need for 190 samples in the modeling (MO) group and 81 samples in the validation (VA) group based on a 7:3 ratio, totaling at least 271 subjects. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital (No. 2022-42), and the Ethics Committee agreed to waive informed consent.

GAD assessment methods: According to the “Chinese Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition[11]” guidelines, the assessment of GAD is based on the following criteria: (1) Persistent excessive anxiety and worry about everyday life for at least 6 months, with a GAD-7 score ≥ 5; (2) Difficulty managing this worry; (3) Presence of at least one of the following symptoms: Restlessness or feeling tense, easy fatigability, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbances; (4) Clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other critical areas of functioning; and (5) Persistent fear of non-specific objects and content. GAD was assessed by a physician unaware of the study specifics.

Data collection: Patients with COPD diagnosed at our hospital were identified via the electronic medical record system. Patient follow-ups were conducted through phone calls and outpatient reviews to ascertain occurrences of GAD. Clinical data, including age, gender, body mass index, educational level, marital status, average household monthly income, living arrangements, smoking history, smoking index, alcohol consumption history, duration of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage, number of exacerbations in the past year, last pulmonary function test results before enrollment (forced expiratory volume in the first second), cardiovascular comorbidities, home oxygen therapy status, understanding of the disease, and personality traits, were collected from electronic health records.

Data collected were analyzed using SPSS (version 27.0). Normally distributed quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups were conducted using independent samples t-tests. Non-normally distributed quantitative data were presented as median (P25, P75) and analyzed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were reported as number or percentage, and comparisons were made using χ2 tests. Multifactorial logistic regression analysis was employed to identify risk factors for GAD occurrence in patients with COPD, with model visualization using forest plots. The predictive model’s fit and efficacy were assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow (H-L) goodness-of-fit test and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The significance level was set at α = 0.05.

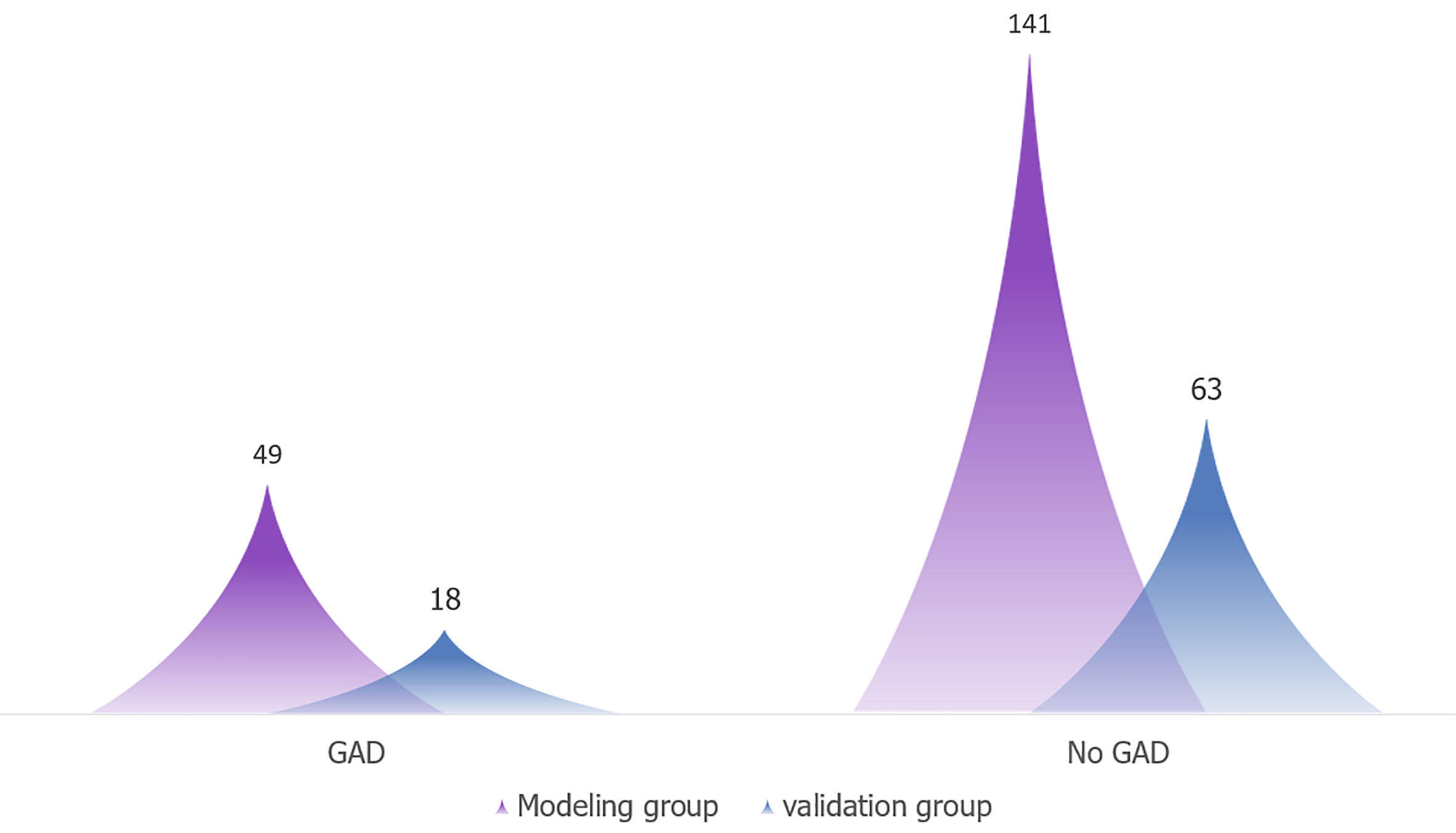

This study ultimately included 271 subjects, comprising 190 in the MO group and 81 in the VA group. A total of 67 patients with COPD developed GAD, representing an incidence rate of 24.72% (67/271). Specifically, 49 cases (18.08%) occurred in the MO group and 18 cases (22.22%) in the VA group, as depicted in Figure 1.

No statistically significant differences were observed in age, gender, and other clinical data between the MO and VA groups (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 1.

| Category | MO groups (n = 190) | VA groups (n = 81) | χ2/t | P value |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18-60 | 28 | 13 | 0.247 | 0.619 |

| > 60 | 122 | 68 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 118 | 52 | 0.106 | 0.744 |

| Female | 72 | 29 | ||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 22.35 ± 1.81 | 22.09 ± 1.94 | 1.059 | 0.290 |

| Educational level | ||||

| Junior high school and below | 57 | 24 | 0.912 | 0.634 |

| Technical/vocational or high school | 112 | 51 | ||

| College and above | 21 | 6 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 151 | 64 | 0.007 | 0.932 |

| Unmarried, divorced, or widowed | 39 | 17 | ||

| Average household income, CNY | ||||

| < 3000 | 98 | 42 | 0.627 | 0.731 |

| 3000-5000 | 62 | 29 | ||

| > 5000 | 30 | 10 | ||

| Living arrangement | ||||

| Living alone | 19 | 9 | 0.799 | 0.671 |

| Living with spouse | 126 | 56 | ||

| Living with children or others | 45 | 26 | ||

| Smoking history | ||||

| Yes | 55 | 22 | 0.089 | 0.765 |

| No | 135 | 59 | ||

| Smoking index, cigarettes/year | ||||

| ≥ 400 | 92 | 38 | 0.052 | 0.820 |

| < 400 | 98 | 43 | ||

| Alcohol history | ||||

| Yes | 36 | 14 | 0.104 | 0.747 |

| No | 154 | 67 | ||

| COPD duration (years) | ||||

| < 5 | 44 | 19 | 0.724 | 0.696 |

| 5-10 | 59 | 29 | ||

| > 10 | 87 | 33 | ||

| GOLD Stage | ||||

| Stage 1 | 13 | 6 | 1.233 | 0.745 |

| Stage 2 | 84 | 39 | ||

| Stage 3 | 54 | 24 | ||

| Stage 4 | 39 | 12 | ||

| Acute exacerbations in the past year | ||||

| 0 or 1 time | 104 | 41 | 0.387 | 0.534 |

| ≥ 2 times | 86 | 40 | ||

| FEV1 (L) | 1.29 ± 0.45 | 1.17 ± 0.58 | 1.837 | 0.067 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | ||||

| Yes | 76 | 31 | 0.020 | 0.889 |

| No | 118 | 50 | ||

| Home oxygen therapy | ||||

| Yes | 29 | 13 | 0.470 | 0.493 |

| No | 118 | 68 | ||

| Understanding of the disease | ||||

| Completely unaware | 27 | 12 | 1.770 | 0.413 |

| Moderately aware | 127 | 59 | ||

| Very aware | 36 | 10 | ||

| Personality | ||||

| Introverted | 116 | 47 | 0.217 | 0.641 |

| Extroverted | 74 | 34 | ||

| GAD | ||||

| Yes | 49 | 18 | 0.041 | 0.840 |

| No | 141 | 63 |

In the MO group, the non-GAD group had higher educational level (χ2 = 12.452, P = 0.002), higher average household income (χ2 = 7.039, P = 0.030), lower smoking history (χ2 = 6.211, P = 0.013), lower smoking index (χ2 = 7.538, P = 0.006), lower number of acute exacerbations in the past year (χ2 = 10.711, P = 0.001), fewer presence of cardiovascular comorbidities (χ2 = 9.966, P = 0.002), better understanding of the disease (χ2 = 49.452, P < 0.001), and more extroverted personalities (χ2 = 10.561, P = 0.001) compared to GAD group, as shown in Table 2.

| Category | GAD group (n = 49) | Non-GAD group (n = 141) | χ2/t | P value |

| Age (yeas) | ||||

| 18-60 | 8 | 20 | 0.133 | 0.716 |

| > 60 | 41 | 121 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 31 | 87 | 0.038 | 0.846 |

| Female | 18 | 54 | ||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 21.97 ± 1.95 | 22.34 ± 1.87 | 1.180 | 0.239 |

| Educational level | ||||

| Junior high school and below | 24 | 33 | 12.452 | 0.002 |

| Technical/vocational or high school | 23 | 89 | ||

| College and above | 2 | 19 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 37 | 114 | 0.636 | 0.425 |

| Unmarried, divorced, or widowed | 12 | 27 | ||

| Average household income, CNY | ||||

| < 3000 | 24 | 74 | 7.039 | 0.030 |

| 3000-5000 | 22 | 40 | ||

| > 5000 | 3 | 27 | ||

| Living arrangement | ||||

| Living alone | 5 | 14 | 0.106 | 0.949 |

| Living with spouse | 32 | 94 | ||

| Living with children or others | 12 | 31 | ||

| Smoking history | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 34 | 6.211 | 0.013 |

| No | 28 | 107 | ||

| Smoking index, cigarettes/year | ||||

| ≥ 400 | 32 | 60 | 7.538 | 0.006 |

| < 400 | 17 | 81 | ||

| Alcohol history | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 27 | 0.014 | 0.904 |

| No | 40 | 114 | ||

| COPD duration (years) | ||||

| < 5 | 11 | 33 | 0.080 | 0.961 |

| 5-10 | 16 | 43 | ||

| > 10 | 22 | 65 | ||

| GOLD Stage | ||||

| Stage 1 | 3 | 10 | 0.259 | 0.968 |

| Stage 2 | 22 | 62 | ||

| Stage 3 | 13 | 41 | ||

| Stage 4 | 11 | 28 | ||

| Acute exacerbations in the past year | ||||

| 0 or 1 time | 17 | 87 | 10.711 | 0.001 |

| ≥ 2 times | 32 | 54 | ||

| FEV1 (L) | 1.19 ± 0.36 | 1.28 ± 0.41 | 1.364 | 0.174 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | ||||

| Yes | 30 | 46 | 9.966 | 0.002 |

| No | 19 | 85 | ||

| Home oxygen therapy | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 21 | 0.058 | 0.810 |

| No | 41 | 120 | ||

| Understanding of the disease | ||||

| Completely unaware | 21 | 6 | 49.452 | < 0.001 |

| Moderately aware | 27 | 100 | ||

| Very aware | 1 | 35 | ||

| Personality | ||||

| Introverted | 39 | 75 | 10.561 | 0.001 |

| Extroverted | 10 | 66 |

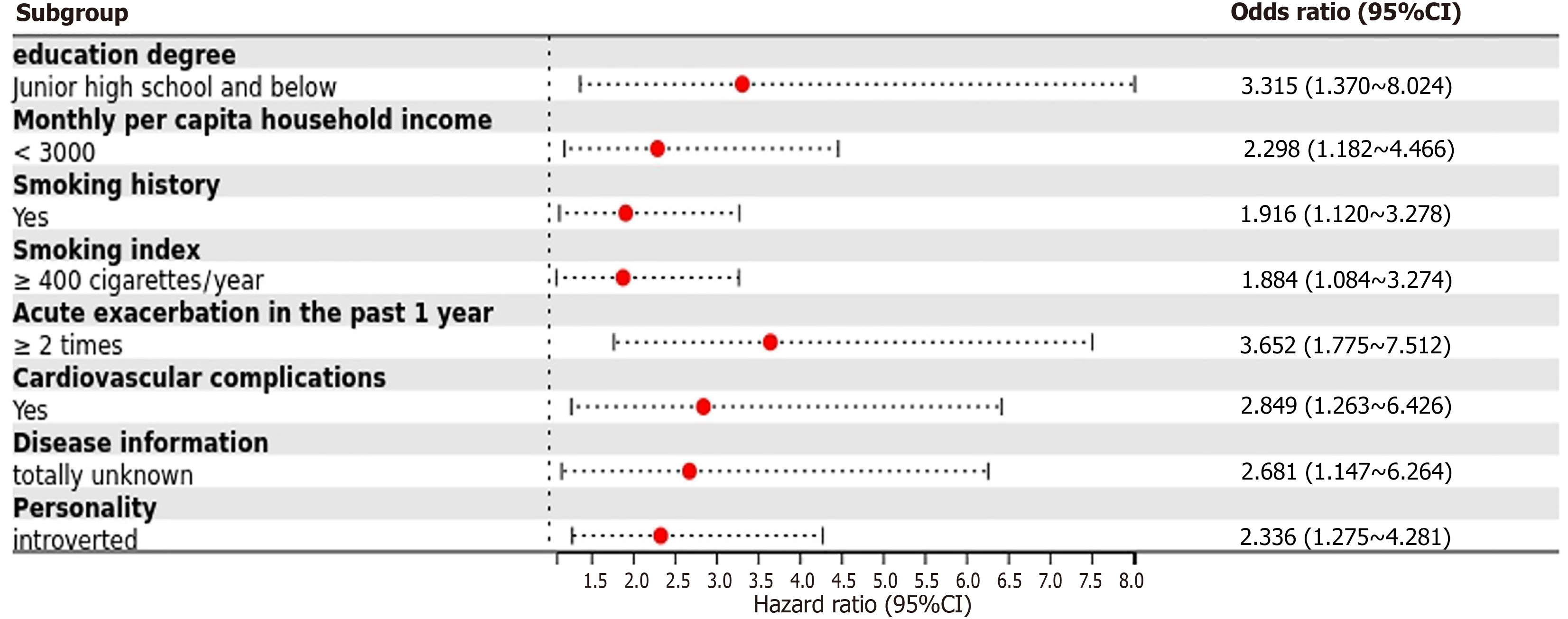

Variables that showed significant differences in the univariate analysis were selected as independent variables in a multifactorial logistic regression analysis, with the occurrence of GAD as the dependent variable (assigned values: Non-GAD = 0, GAD = 1). The results indicated that educational level of middle school or below, household income < 3000 China yuan (CNY), smoking history, smoking index ≥ 400 cigarettes/year, ≥ two acute exacerbations in the past year, presence of cardiovascular comorbidities, complete lack of disease information, and introverted personality type were significant risk factors for the development of GAD in the MO group (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 3.

| Factors | β | SE | Ward χ2 | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Educational level (junior high school and below) | 1.198 | 0.451 | 7.061 | 0.009 | 3.315 | 1.370-8.024 |

| Average household monthly income (< 3000 CNY) | 0.832 | 0.339 | 6.024 | 0.014 | 2.298 | 1.182-4.466 |

| Smoking history | 0.650 | 0.274 | 5.632 | 0.019 | 1.916 | 1.120-3.278 |

| Smoking index (≥ 400 cigarettes/year) | 0.633 | 0.282 | 5.045 | 0.024 | 1.884 | 1.084-3.274 |

| Acute exacerbations in the past year (≥ 2 times) | 1.295 | 0.368 | 12.389 | < 0.001 | 3.652 | 1.775-7.512 |

| Presence of cardiovascular comorbidities | 1.047 | 0.415 | 6.365 | 0.010 | 2.849 | 1.263-6.426 |

| Understanding of the disease (completely unaware) | 0.986 | 0.433 | 5.187 | 0.021 | 2.681 | 1.147-6.264 |

| Personality (introverted type) | 0.848 | 0.309 | 7.539 | 0.005 | 2.336 | 1.275-4.281 |

The results of multifactorial logistic regression analysis indicated that variables including educational level, household income, smoking history, smoking index, number of acute exacerbations in the past year, cardiovascular comorbidities, understanding of the disease, and personality were incorporated into the prediction model. The forest plot model was established, as depicted in Figure 2.

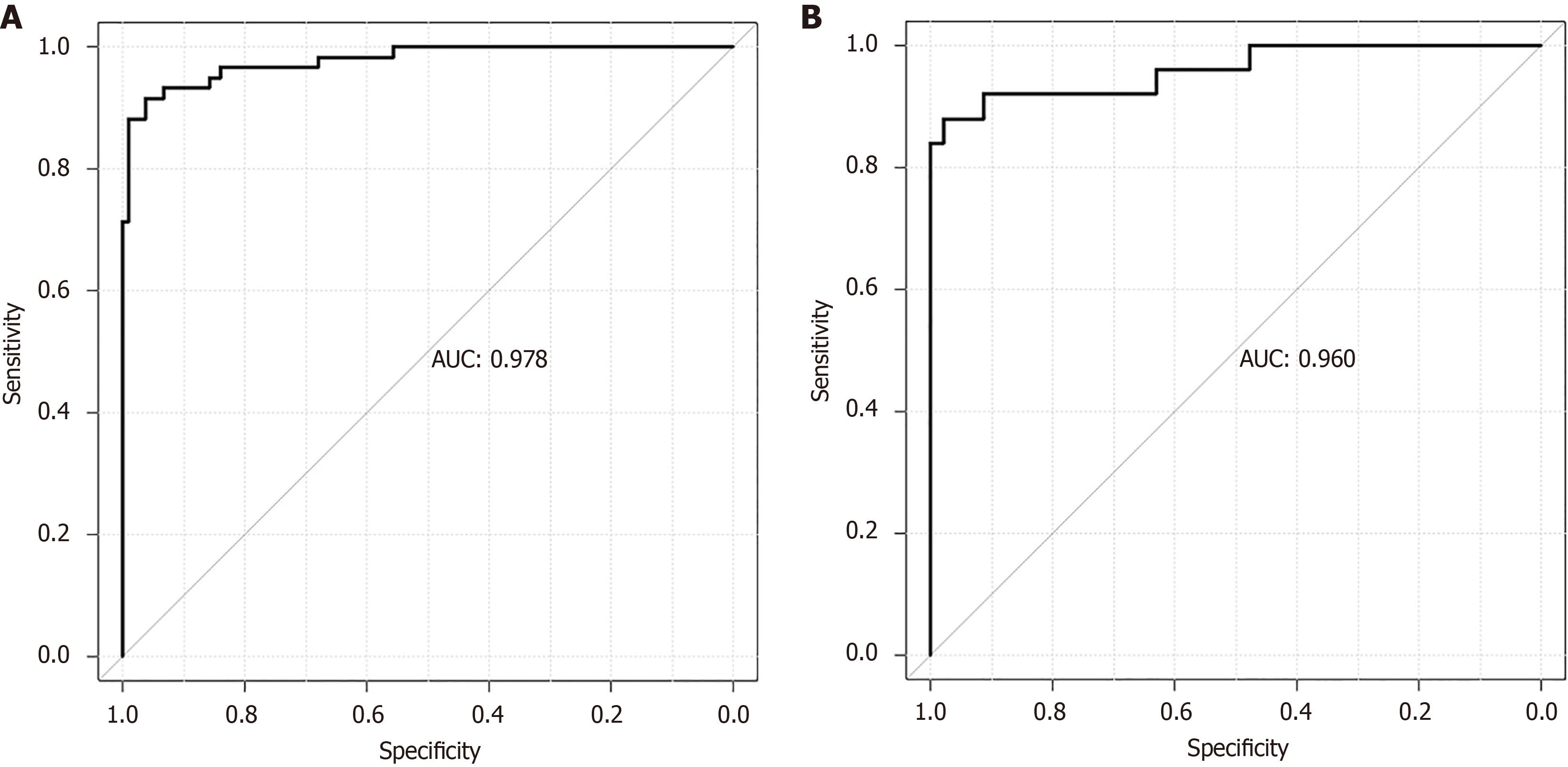

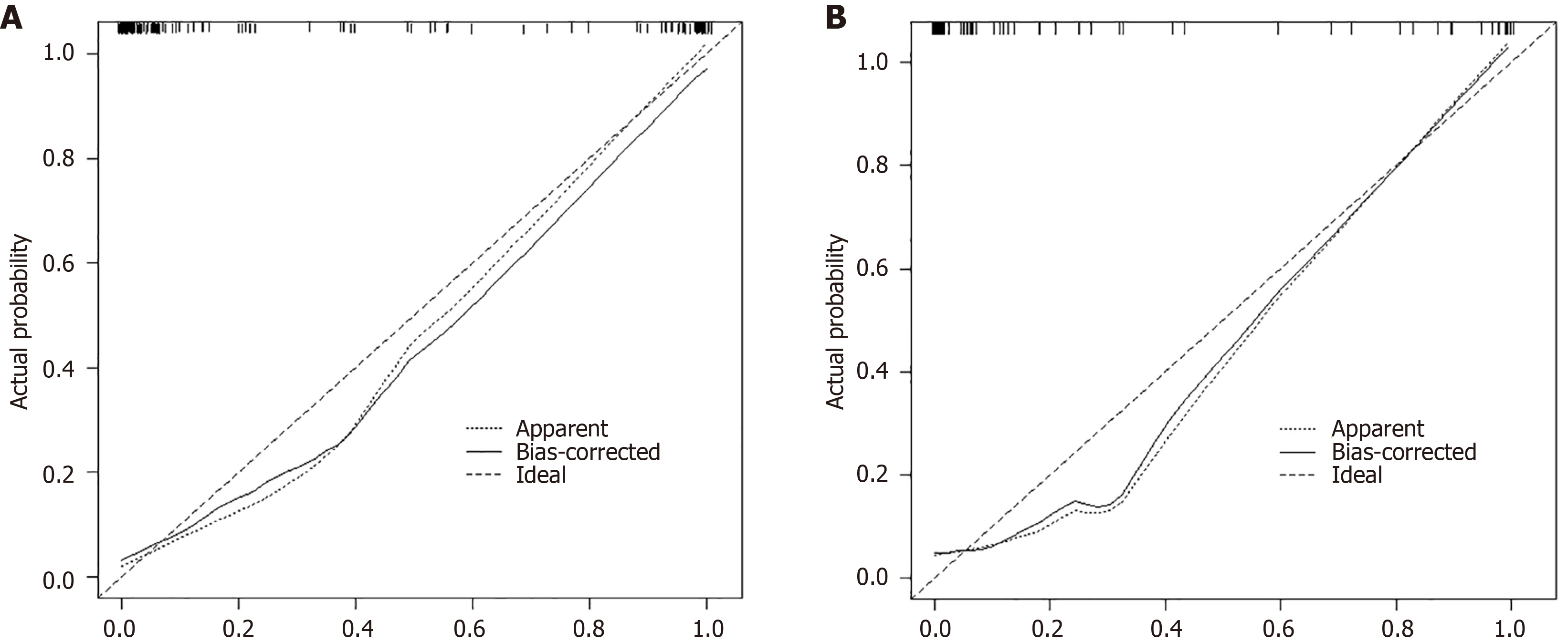

The ROC analysis showed that the area under the curve (AUC) values for predicting GAD occurrence in the MO and VA groups were 0.978 and 0.960, respectively, indicating good internal and external validity and predictive ability of the model, as shown in Figure 3. The predictive model underwent H-L testing, yielding χ2 values of 6.511 and 5.179, with P values of 0.275 and 0.274 (P > 0.05), indicating good fit of the model in both groups, with no significant deviation from actual conditions. The calibration curves further demonstrated the model’s accuracy in predicting the risk of GAD occurrence compared with actual events, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Patients with COPD frequently face challenges related to anxiety disorders, which are linked to disease exacerbation. Epidemiological data suggest a high incidence of anxiety comorbidity in patients with COPD, with rates of associated depression ranging from 10% to 42% during stable phases and from 10% to 86% during exacerbations. Anxiety rates range from 13% to 46% during stable periods and from 10% to 55% during exacerbations[12]. In the present study, out of 271 patients, 67 developed GAD, an incidence of 24.72% (67/271). This rate is comparable to findings reported in the literature[13]. Studies indicate[14] that patients with COPD with anxiety not only lack confidence and have reduced disease coping and self-management capabilities but also exhibit decreased compliance, physical capacity, quality of life, and work capacity. Moreover, these patients face increased risks of acute exacerbations and mortality. Hence, the selection of reliable assessment tools is critical. While tools, such as the GAD-7 scale, are commonly used for screening, their reliance on self-reported patient data introduces a degree of subjectivity[15]. Logistic regression analysis, a statistical method that evaluates independent disease risk factors and quantifies the contributions of covariates through a predictive model, has been widely employed to predict complications in patients with chronic diseases[16,17].

Following univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, this study identified factors influencing the onset of GAD in the MO group. Significant risk factors included an educational level of middle school or below, household income < 3000 CNY, smoking history, a smoking index of ≥ 400 cigarettes/year, ≥ two acute exacerbations in the past year, cardiovascular comorbidities, a complete lack of disease knowledge, and an introverted personality. These findings are consistent with those of Husain et al[18]. Educational level reflects the degree of understanding of the disease and the mastery of disease-specific knowledge. Due to COPD’s unique clinical manifestations, the chronic and worsening nature of the condition, and the experience of breathlessness, patients often perceive their condition as severe, leading to complex and unclear emotional responses. Additionally, patients with lower educational levels tend to have poor emotional self-regulation capabilities, which can lead to anxiety[19]. In the present study, patients with lower educational levels or a complete lack of disease knowledge had a significantly higher incidence of GAD, likely because these patients have limited understanding of the disease’s pathogenesis and progression, and they are unable to effectively manage their condition, thus experiencing increased anxiety and fear. Research also shows a close association between smoking and anxiety[20]. In a study by Uchmanowicz et al[21], among 102 patients with COPD, 50% had been smoking for over 15 years, with 39.3% smoking 10-20 cigarettes per day and 31.4% smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day. Spearman analysis identified smoking as an independent predictor of anxiety comorbidity in COPD. Lou et al’s study[22] indicated that the interaction between smoking and anxiety increased mortality risk in patients with COPD, with risk escalating with the number of years or packs smoked. Cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension and arrhythmias, may disrupt physiological functions and affect neural transmission and chemical release in the brain, thus increasing the risk of anxiety disorders[23]. A survey on the social characteristics of patients with COPD noted[24] that introverted patients tend to internalize emotions, are less adept at expressing and managing negative emotions, and are more likely to accumulate anxiety and stress than extroverted individuals, thus increasing their risk of developing GAD.

This study utilized multifactorial logistic regression analysis results as predictors to develop a forest plot predictive model, evaluated its performance by using ROC curves, H-L goodness-of-fit tests, and calibration curves. The ROC analysis revealed that the AUC values for the prediction of GAD occurrence in the MO and VA groups were 0.978 and 0.960, respectively, indicating good efficacy in internal and external VAs and robust predictive capability. Clinically, the H-L test is employed to assess the performance of a model. P > 0.05 suggests that the model predictions closely match actual occurrences, indicating high calibration and an ideal model fit. Conversely, P ≤ 0.05 indicates a discrepancy between model predictions and actual occurrences, signifying low calibration. In this study, the H-L test produced χ2 values of 6.511 and 5.179, with P = 0.275 and 0.274, respectively, suggesting that the model fits well in the MO and VA groups, with no significant differences from actual conditions. Furthermore, the calibration curves demonstrated good consistency between the predicted risks of GAD occurrence and actual events.

Despite successfully identifying important predictors of GAD and constructing a prediction model with high accuracy, this study has several limitations. First, the retrospective design of the study may be subject to recall bias. Second, due to limitations in data collection, we were unable to perform detailed subgroup analyses based on patient characteristics such as age, sex, and disease severity, which may have overlooked risk factors in specific subpopulations. Future studies should consider using a prospective design and conducting more detailed subgroup analyses to further explore how these variables influence the risk of GAD in COPD patients.

Establishing a predictive model for GAD risk in patients with COPD is essential, and it can provide a scientific basis for clinical practice to reduce the risk of anxiety disorders. The risk prediction model developed in this study includes eight independent risk factors: Educational level, household income, smoking history, smoking index, number of acute exacerbations in the past year, presence of cardiovascular comorbidities, understanding of the disease, and personality traits. The model performs well, effectively predicting the occurrence of GAD in patients with COPD, and it can aid in the early screening of high-risk individuals, thus providing a basis for early preventive interventions by nursing staff. Future research could integrate new indicators and technologies to further refine and optimize the predictive model, enhancing its accuracy and practicality.

| 1. | Ritchie AI, Wedzicha JA. Definition, Causes, Pathogenesis, and Consequences of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41:421-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 41.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen S, Kuhn M, Prettner K, Yu F, Yang T, Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE, Wang C. The global economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for 204 countries and territories in 2020-50: a health-augmented macroeconomic modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11:e1183-e1193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 93.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Duffy SP, Criner GJ. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Evaluation and Management. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:453-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Riley CM, Sciurba FC. Diagnosis and Outpatient Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2019;321:786-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | DeMartini J, Patel G, Fancher TL. Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:ITC49-ITC64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li Z, Liu S, Wang L, Smith L. Mind-Body Exercise for Anxiety and Depression in COPD Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu M, Wang D, Fang J, Chang Y, Hu Y, Huang K. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 in patients with COPD: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Homętowska H, Klekowski J, Świątoniowska-Lonc N, Jankowska-Polańska B, Chabowski M. Fatigue, Depression, and Anxiety in Patients with COPD, Asthma and Asthma-COPD Overlap. J Clin Med. 2022;11:7466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Christodoulou E, Ma J, Collins GS, Steyerberg EW, Verbakel JY, Van Calster B. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;110:12-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 935] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 164.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu M, Li Y, Yin D, Wang Y, Fu T, Zhu Z, Zheng C, Huang K. COPD Assessment Test as a Screening Tool for Anxiety and Depression in Stable COPD Patients: A Feasibility Study. COPD. 2023;20:144-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen YF. Chinese classification of mental disorders (CCMD-3): towards integration in international classification. Psychopathology. 2002;35:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yohannes AM, Murri MB, Hanania NA, Regan EA, Iyer A, Bhatt SP, Kim V, Kinney GL, Wise RA, Eakin MN, Hoth KF; COPDGene Investigators. Depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with COPD: A network analysis. Respir Med. 2022;198:106865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zanaboni P, Dinesen B, Hoaas H, Wootton R, Burge AT, Philp R, Oliveira CC, Bondarenko J, Tranborg Jensen T, Miller BR, Holland AE. Long-term Telerehabilitation or Unsupervised Training at Home for Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207:865-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Poot CC, Meijer E, Kruis AL, Smidt N, Chavannes NH, Honkoop PJ. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;9:CD009437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu D, Zhao X, Huang D, Dai Z, Chen M, Li D, Wu B. Outcomes associated with comorbid anxiety and depression among patients with stable COPD: A patient registry study in China. J Affect Disord. 2022;313:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tian YE, Cropley V, Maier AB, Lautenschlager NT, Breakspear M, Zalesky A. Heterogeneous aging across multiple organ systems and prediction of chronic disease and mortality. Nat Med. 2023;29:1221-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 107.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xu C, Zheng L, Jiang Y, Jin L. A prediction model for predicting the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome in sepsis patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Husain MO, Chaudhry IB, Blakemore A, Shakoor S, Husain MA, Lane S, Kiran T, Jafri F, Memon R, Panagioti M, Husain N. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their association with psychosocial outcomes: A cross-sectional study from Pakistan. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211032813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Samudio-Cruz MA, Toussaint-González P, Estrada-Cortés B, Martínez-Cortéz JA, Rodríguez-Barragán MA, Hernández-Arenas C, Quinzaños-Fresnedo J, Carrillo-Mora P. Education Level Modulates the Presence of Poststroke Depression and Anxiety, But It Depends on Age. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2023;211:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, Munafò MR. The Association of Cigarette Smoking With Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:3-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 675] [Cited by in RCA: 847] [Article Influence: 94.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Uchmanowicz I, Jankowska-Polanska B, Motowidlo U, Uchmanowicz B, Chabowski M. Assessment of illness acceptance by patients with COPD and the prevalence of depression and anxiety in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:963-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lou P, Chen P, Zhang P, Yu J, Wang Y, Chen N, Zhang L, Wu H, Zhao J. Effects of smoking, depression, and anxiety on mortality in COPD patients: a prospective study. Respir Care. 2014;59:54-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen X, Xu L, Li Z. Autonomic Neural Circuit and Intervention for Comorbidity Anxiety and Cardiovascular Disease. Front Physiol. 2022;13:852891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Suerdem M, Gunen H, Akyildiz L, Cilli A, Ozlu T, Uzaslan E, Abadoglu O, Bayram H, Cimrin AH, Gemicioglu B, Misirligil Z. Demographic, Clinical and Management Characteristics of Newly Diagnosed COPD Patients in Turkey: A Real-Life Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:261-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/