CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 36-year-old woman with PMS presented with developmental delays, mood instability, manic episodes, and impulsive behavior.

History of present illness

The patient was a 36-year-old woman. According to her family’s statement, she could only point and make sounds by age 2 years, said her first word ("mama") at age 3 years, and began walking at the same age. In early childhood, she was often silent, seldom speaking, and had minimal social interaction. Upon starting elementary school, she demonstrated poor academic performance, being unable to perform simple arithmetic (e.g, addition and subtraction within 100) or navigate outside independently. Her daily living activities required family assistance. She was not taken for medical evaluation and dropped out of school after the sixth grade. She continued to live under family care, capable of basic self-care, including dressing, eating, and following simple instructions. At age 18 years, she first exhibited noticeable emotional instability, including excessive talking, grandiosity, hyperactivity, frequent shouting, and reduced sleep (2-3 hours per night) without fatigue. These episodes, which lasted approximately one month, alternated with periods of withdrawal and sparse speech. She was hospitalized during this period and diagnosed with: (1) Intellectual disability with significant behavioral issues requiring attention or treatment; and (2) Bipolar disorder, manic episode without psychotic features. Her IQ, assessed via the Wechsler Intelligence Scale, was 54. Treatment included Clozapine and Oxcarbazepine, although her family could not provide specific dosages. She discontinued medication within 6 months. During remission periods, she displayed stable behavior, used simple speech, and managed limited independence with family support. At 23 years old, she married and gave birth to a daughter at 24 years old. After childbirth, she relapsed, presenting with hyperactivity, excessive talking, disorganized speech, impulsive spending, and insistence on purchasing unnecessary items (e.g., large quantities of toilet paper). She was hospitalized and received treatment for 2 months, after which her symptoms improved. Maintenance therapy with Clozapine (25-75 mg/day) continued until June 2021. In mid-2021, her condition worsened, with symptoms of irritability, excessive talking, shouting, wandering, and insomnia. She was hospitalized in August 2021 and treated with Lurasidone (40-80 mg/day), Clozapine (25-100 mg/day), Oxcarbazepine (1.2 g/day), and Lorazepam (2 mg/day). Despite treatment, her symptoms persisted, characterized by emotional instability and loud outbursts. On December 2021, she developed marked psychomotor slowing and a stiff gait. Medications were adjusted, discontinuing Clozapine and Lurasidone and introducing Olanzapine (5-20 mg/day) over two weeks. However, her condition further deteriorated, with worsening insomnia, continuous screaming, limb rigidity, abnormal hand posturing, and dysphagia. The patient was first admitted to our hospital.

On January 17, 2022, she was unconscious, disoriented, and displayed generalized rigidity. She was unable to speak, had a tense facial expression, could not eat independently, experienced difficulty swallowing, and persistently vocalized with repetitive "ah, ah" sounds. During her initial hospitalization, the patient was diagnosed with the following: (1) NMS; and (2) Intellectual disability with significant behavioral impairments requiring medical attention. At this stage, diagnosis of bipolar disorder was not made because the patient was unconscious and did not exhibit symptoms of mania. Following treatment, she exhibited a slight improvement in emotional stability. While her emotional stability improved slightly, significant impairments persisted, including the inability to perform daily self-care, feed herself, or void independently, alongside sustained rigid flexion spasms and increased muscle tone. Subsequently, her family transferred her to a general hospital, where she underwent additional rehabilitation for 5 months.

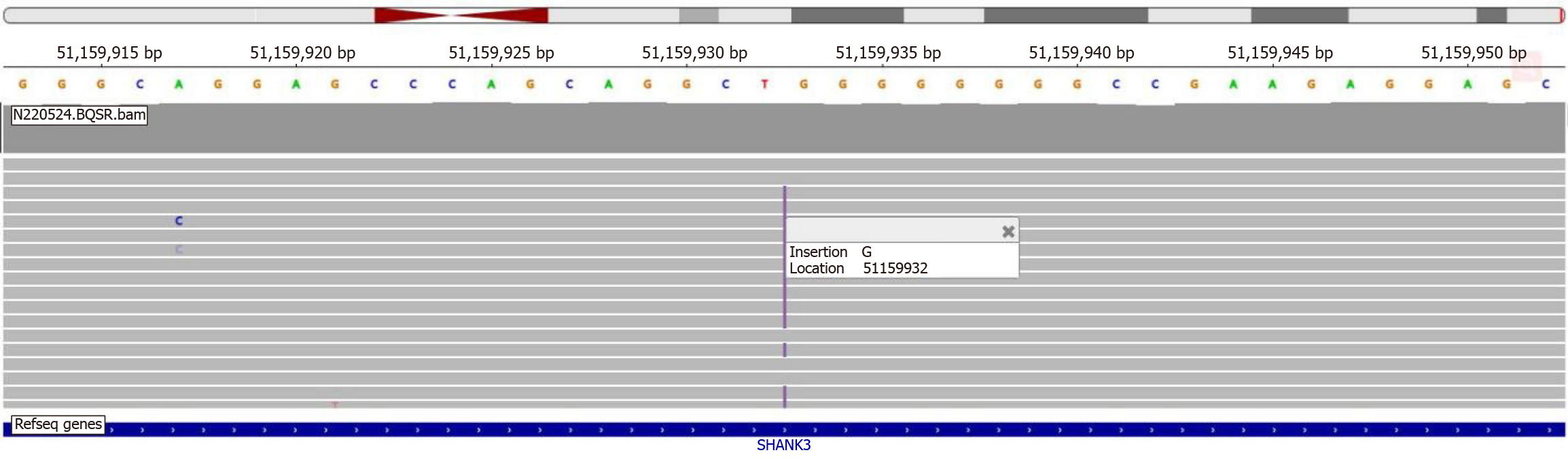

During her hospitalization at the rehabilitation hospital, on the basis of the patient's developmental delay, recurrent manic episodes, decline in daily living skills, and persistent high muscle tone in her limbs, whole-exome sequencing was performed in April 2022. This revealed a mutation in the SHANK3 gene (c.3865dup), aligning with her clinical presentation, as illustrated in Figure 1. The diagnosis of PMS was confirmed. She was treated with Lithium carbonate sustained-release tablets (0.3-0.6 g/day) along with ongoing rehabilitation therapy and was discharged for continued care in July 2022. At the time of discharge, her mood was more stable than prior to hospitalization, and she had regained the ability to urinate and defecate independently, allowing for the removal of the urinary catheter. However, her swallowing remained slow, requiring a nasogastric tube for feeding, and she could not speak in complete sentences. She occasionally said simple words, such as "daughter" or "mom" and intermittently screamed "ah ah". She spent most of her time in bed, and community healthcare workers continued to visit regularly to care for her nasogastric tube. In November 2022, significant improvements were noted in her condition. Her mood had further been stabilized, and she was able to speak simple words to her family. She also regained the ability to eat independently, which led to the removal of the nasogastric tube. However, she still exhibited elevated muscle tone, walked unsteadily, and was at risk of falling. Her nutritional status improved, with a 20-pound weight gain over 11 months following her discharge. It took approximately 13 months for her walking instability to significantly improve. Throughout this period, she received Lithium carbonate (0.6 g/day) and was able to manage her personal hygiene with assistance from her family. Her overall condition remained stable.

Figure 1 Integrative genomics viewer diagram showing sequencing results for the SHANK3 gene variant c.3865dup in the subject.

In January 2024, the patient experienced a relapse. Over the course of a week, she exhibited enhanced excitement, spoke loudly and incessantly, yelled, cursed at family members, and engaged in destructive behaviors, such as smashing objects. She frequently made sexually suggestive remarks, slept only 2-3 hours per night, and remained highly energetic during the day, running around the house continuously. In February 2024, she was admitted to the hospital for the second time. she displayed symptoms consistent with manic syndrome.

History of past illness

The patient had a history of intellectual disability, while without history of cardiac, endocrine, or other systemic diseases.

Personal and family history

Findings from the initial admission evaluation were unremarkable.

Physical examination

During the initial examination, the patient’s condition significantly worsened. On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 38.8 °C; blood pressure, 170/110 mmHg; heart rate, 100-130 beats per min; body weight, 45 kg; and height, 158 cm. She experienced urinary and fecal incontinence. Her right hand assumed a claw-like posture, muscle tone was markedly enhanced, and she exhibited rigid flexion spasms. In February 2024, the patient was admitted to the hospital for the second time. On physical examination, no significant abnormalities were detected.

Laboratory examinations

On January 17, 2022, routine blood tests revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 4.37 × 109/L, a red blood cell (RBC) count of 3.91 × 1012/L, a hemoglobin level of 106 g/L, and an elevated platelet count of 267 × 109/L. Blood biochemistry on the same day indicated significantly elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 62.5 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST; 136.3 U/L), creatine kinase (CK; 11154 U/L), and CK-MB isoenzyme (CK-MB; 218.21 U/L). On January 18, 2022, blood gas analysis, female tumor markers, and thyroid function tests were all within normal ranges. Electroencephalogram, performed on January 19, 2022, indicated increased fast waves. Routine cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, CSF biochemistry, and autoimmune encephalitis antibody tests, conducted on February 1, 2022, all returned normal results. Subsequent blood tests indicated progressive improvement. On February 12, 2022, routine blood examination revealed a WBC count of 5.08 × 109/L, an RBC count of 3.95 × 10¹²/L, a hemoglobin level of 134 g/L, and a platelet count of 192 × 109/L. Blood biochemistry results included an ALT level of 16.3 U/L, an AST level of 19.3 U/L, a CK level of 413 U/L (mildly elevated), and a CK-MB level of 15.9 U/L. On February 21, 2022, routine blood tests revealed a WBC count of 5.92 × 109/L, an RBC count of 3.95 × 10¹²/L, a hemoglobin level of 124 g/L, and a platelet count of 212 × 109/L. Blood biochemistry results were summarized as follows: An ALT level of 17.1 U/L, an AST level of 22.1 U/L, a CK level of 263 U/L (mildly elevated), and a CK-MB level of 17.74 U/L. These findings indicate a consistent trend toward the normalization of laboratory parameters over time. Laboratory tests, including routine bloodwork and metabolic panels, were normal. In February 2024, the patient was hospitalized for the second time. Her Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale (BRMS) score was 26, indicative of a moderate-to-severe manic episode.

Imaging examinations

Magnetic resonance imaging of the head revealed slight white matter hyperintensity of vascular origin in both lateral ventricles, classified as Fazekas grade 1.

DISCUSSION

This 36-year-old woman had a history of delayed mental development since childhood and multiple manic episodes beginning in early adulthood. In 2022, she experienced a regression in life skills over a period of more than a year, followed by another manic episode. To better understand her diagnosis and treatment, three essential questions need to be addressed: What is her diagnosis? What treatment is appropriate for her? How can similar patients be identified for early intervention?

Intellectual disability is a prevalent feature in patients with generalized developmental disorders, such as PMS, mainly manifesting as severe or profound[7,8]. Additionally, several patients experience episodes of decompensation, including mood instability, irritability, and erratic behaviors. The patient’s symptoms are consistent with the psychiatric manifestations commonly associated with PMS[9]. Research indicated that approximately 54% of PMS patients with psychiatric symptoms may meet the diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder. Notably, bipolar disorder could be more prevalent in individuals with large deletions of the SHANK3 gene (3%), compared with those with small deletions or SHANK3 sequence variants (16%)[10]. In these patients, behaviors, such as frequent screaming, sudden bursts of activity, and an inability to remain still are often identified, typically due to intellectual disabilities[11,12]. Although case reports have been the primary source of information on PMS with comorbid psychiatric disorders, a study of 38 adolescents and adults with PMS found common psychiatric manifestations, such as emotional instability, catatonia, and significant skill loss, primarily triggered by infections, hormonal changes, or stress[4]. A recent review found that bipolar disorder is common in patients with PMS, typically emerging during adolescence or early adulthood[3]. While there is a possible link between PMS and bipolar disorder, further research is needed to understand their overlapping symptoms[13,14]. Intellectual disability can obscure the presentation of bipolar symptoms, complicating both diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment that includes detailed clinical observation and the use of multiple diagnostic tools is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

PMS can lead to neurological and psychiatric deterioration, affecting cognition, speech, motor skills, and daily living abilities, with speech regression often occurring first[15,16]. A previous study on PMS patients indicated that 43% experienced regression[15], which is a recognized characteristic of the PMS. These regressions can be triggered by biological factors, such as fever, infections, hormonal changes, and NMS, as well as environmental factors[17]. In early 2022, this patient experienced a decline in speech and daily living skills following antipsychotic treatment and lung infection, while improved over the year. In contrast to other cases of PMS, this patient experienced NMS, which might be triggered during the transition among lurasidone, clozapine, and olanzapine. Moreover, the patient presented with impaired consciousness, high fever, muscle rigidity, autonomic dysfunction, and pulmonary infection[18]. Following this episode, she exhibited regression in both language abilities and daily living skills. Although there have been no prior studies linking PMS to NMS, this severe adverse reaction highlights the importance of exercising caution when adjusting medications in PMS patients. In early 2023, the patient's speech and behavioral abilities returned to normal, enabling her to communicate, eat, use the restroom, and walk outside. PMS-related regression can occur at any age, mainly commencing in middle childhood and impacting cognition, speech, motor skills, and daily living activities[15,19]. Persistent deficits may be attributed to SHANK3 gene haploinsufficiency, affecting recovery from psychiatric and physical events[16]. Although approximately half of affected cases partially regain social functions within three years, psychiatric issues typically persist[4,20].

The diagnosis of PMS is primarily confirmed through molecular genetic testing, such as chromosomal microarray analysis and next-generation sequencing for genome copy number variation. Additionally, for detected deletions, further testing may be needed to assess the extent of the deletions[21]. In this case, the patient underwent whole-exome sequencing in April 2022, which identified a SHANK3 gene mutation (c.3865dup), a loss-of-function frameshift mutation, ultimately leading to a definitive diagnosis of PMS.

PMS management guidelines recommend the utilization of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics for mood disorders. Mood stabilizers, either alone or in combination with antipsychotics, can stabilize mood and behavior in bipolar disorder, while antipsychotic monotherapy is less effective and poorly tolerated[6]. There is a case report that lithium salt reversed the degenerative symptoms and stabilized the patient's behavior. Two patients were administered lithium at doses of 1.5 and 1.0 g/day, and after two years, one patient even recovered to the level of functioning before the occurrence of degeneration[22]. Other PMS patients with emotional instability, hyperactivity, and sleep disturbances have exhibited improvement with lithium doses of 0.4 and 0.7 g/day, with reports indicating that lithium can reverse regression symptoms[23,24]. In 2022, the patient experienced NMS following changes in her antipsychotic medication. Treatment involved discontinuing Olanzapine, initiating hydration, and administering modified electroconvulsive therapy, which helped stabilize her mood and restore her consciousness. Lithium sustained-release tablets were later introduced as part of her rehabilitation. During her 2024 hospitalization, the patient received olanzapine (1.25-5 mg/day) plus lithium sustained-release tablets (0.3-0.9 g/day) using a cautious incremental dosing strategy to minimize extrapyramidal side effects. Second-generation antipsychotic medications can aid in acute stabilization in such cases; however, they should be administered at very low doses due to the risk of triggering catatonia and the generally high incidence of side effects[25]. This patient had mental retardation since childhood, accompanied by poor cognitive function. Magnetic resonance imaging of the skull revealed mild white matter hyperintensities near both lateral ventricles, likely of vascular origin. Structural brain abnormalities are frequently found in patients with PMS, including cortical atrophy, white matter changes, ventricular enlargement, reduced volume of the striatum and left pallidum, and mild cerebellar ectopia. Jesse et al[26] demonstrated that the brain white matter changes were particularly significant in PMS patients, mainly concentrated in the long-range fiber bundles, especially the uncinate fasciculus and fronto-suboccipital fasciculus. Insulin is an important neuropeptide in the central nervous system, influencing the balance of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and regulating the secretion of neurotrophic factors and neurotransmitters[27]. Scholars found that insulin can regulate the synaptic plasticity by upregulating the expression levels of receptors related to synaptic plasticity and post-translational modification[28]. According to this evidence, peripheral intravenous insulin was administered to this patient to enhance cognitive function, recognizing as a strategy referenced in PMS management. Preventing infections is crucial for PMS patients, as infections can trigger regression. Behavioral interventions are vital for managing aggression, repetitive actions, and self-injurious behaviors, mainly guided by the Applied Behavior Analysis principles and reinforced behavioral plans[29,30]. Regression in PMS frequently leads to significant deterioration in life skills, necessitating long-term rehabilitation. In some cases, nasogastric tube care provided by community healthcare centers. Comprehensive management, including behavioral therapies, infection prevention, and ongoing medical and rehabilitative support, is vital to maintain the quality of life and address the complex needs of PMS patients.