Published online Feb 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.100859

Revised: November 27, 2024

Accepted: December 20, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2025

Processing time: 138 Days and 16.1 Hours

Work-family conflicts and daytime sleepiness are related to the risk of suicide. At present, no study has investigated the relationship between nurses’ work-family behavioral role conflict and suicide risk. Moreover, it has not been confirmed whether, considering the effect of daytime sleepiness on suicide risk, daytime sleepiness mediates the effect of work-family behavioral role conflict and suicide risk.

To explore the pathway relationships among nurses' work-family behavioral role conflict, daytime sleepiness, and suicide risk.

Convenience and purposive sampling methods were used to select 750 nurses from six provinces, including Jiangxi, Sichuan, and Shanxi. The work-family behavioral role conflict scale, the Chinese adult daytime sleepiness scale, and the suicide behavior questionnaire were used for the survey. The data were statistically analyzed via SPSS 25.0 software, Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore the correlations between the variables, the PROCESS 4.0 program was used for the mediation effect analysis, and the mediation effect model was tested via the bootstrap method.

Nurses' work-family behavioral role conflict and daytime sleepiness were posi

The results of the Pearson correlation analysis and mediation effect analysis revealed that nurses' work-family behavioral role conflict has a direct effect on suicide risk and indirectly affects suicide risk through daytime drowsiness symptoms.

Core Tip: We found that nurses' work-family behavioral role conflict and daytime sleepiness were strongly associated with suicide risk and that daytime sleepiness mediated the relationship between nurses' work-family behavioral role conflict and suicide risk. This study provides a reference basis for improving nurses' mental health by exploring the pathways that influence nurses' suicide risk.

- Citation: Gan QW, Yuan YL, Li YP, Du YW, Zheng LL. Work-family behavioral role conflict and daytime sleepiness on suicide risk among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(2): 100859

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i2/100859.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.100859

Suicide is the intention, thought, or action of an individual to actively end his or her life. According to research reports, approximately 800000 people worldwide die by suicide every year, accounting for 1.5% of all deaths, and suicide has also become the fourth leading cause of death for young people worldwide[1]. In China, although the suicide rate has decreased in recent years, suicide remains a major public health and social problem[2]. Suicide risk is an important predictor of mortality and has been explored in different occupations worldwide, with studies demonstrating that certain work factors are associated with suicide risk[3]. Work-family behavioral role conflict (WFBRC) is a role conflict that occurs when an individual is faced with an inability to balance the demands of the work and family domains; this conflict differs from the traditional concept of work-family conflict, for which assessment tools focus on the measurement of an individual's subjective perceptions and neglect objective specific behavioral conflicts[4]. Nursing involves long working hours, high pressure, and many night shifts, which make nursing staff more prone to WFBRC, thus increasing the psychological burden on these caregivers[4]. Daytime sleepiness refers to an uncontrollable sleepiness reaction of an individual during the day, which has become a global health problem[5]. Nursing staff's sleep disorders are exacerbated by long-term night shift rotation and heavy workloads, and they are unable to quickly return to their normal sleep cycle after night shifts, which, in turn, increases the incidence of daytime sleepiness[6]. Daytime sleepiness can affect nurses' work status and mental health and is associated with suicide risk[5].

Research has demonstrated that both work-family conflict[3] and daytime sleepiness[5] are associated with suicide risk; however, no study has explored the relationship between WFBRC and suicide risk, and it has not yet been demonstrated whether daytime sleepiness mediates the effect between WFBRC and suicide risk when the effect of daytime sleepiness on suicide risk is considered. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed in this study: (1) Chinese nurses' WFBRC and daytime sleepiness are positively associated with suicide risk; (2) WFBRC and daytime sleepiness positively predict suicide risk; and (3) Daytime sleepiness mediates the relationship between WFBRC and suicide risk among Chinese nurses.

This was a multicenter cross-sectional study. From May to June 2024, convenience and purposive sampling methods were used to select nurses from tertiary-level hospitals in six provinces of China as the research subjects. We selected two northern provinces of China (Shanxi and Shaanxi), two southern provinces (Jiangxi and Guangdong), one southeastern coastal province (Zhejiang), and one southwestern inland province (Sichuan) on the basis of China's geographic location via convenience sampling. To select hospitals, we used purposive sampling to select tertiary-level hospitals affiliated with medical universities in each province for the survey. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Nurses who have obtained nursing licenses; and (2) Nurses who voluntarily participated in this study. The exclusion criteria included: (1) Nurses who were on vacation during the study period; (2) Internship nurses; and (3) Nurses who could not complete this study for personal reasons. The rejection criterion was that the questionnaire answers were incomplete or duplicate. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (ethics number: IIT2024235).

This study included sociodemographic information and a total of 17 independent variables. According to the Kendall sample estimation method[7], the sample size was 5-10 times the number of independent variables, and the sample size was 102-204 cases considering a 20% lost visit rate. In this study, 772 questionnaires were distributed, and 750 valid questionnaires were recovered after invalid questionnaires were excluded, for a questionnaire recovery rate of 97.15%.

General information: We designed our questionnaire on the basis of published literature[4,5] and expert opinion. The questionnaire consisted of sociodemographic information such as gender, age, job title, and years of work.

WFBRC scale: Using Zhang’s simplified version[8] of the WFBRC scale in 2023, the scale includes 19 items in 2 dimensions: The impact of work on the family and the impact of family on work. The items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), with a total score of 19 to 95, with higher scores indicating higher levels of WFBRC in individuals. The Cronbach's α coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.943.

Chinese adult daytime sleepiness scale: This scale was adapted from the Chinese adolescent daytime sleepiness scale by Wang et al[9] to assess the degree of daytime sleepiness of shift workers in the past month and has been successfully applied in nurses[6]. The scale consists of 7 items, each of which is scored on a 1-5 scale, with a total score of 7-35, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of daytime sleepiness. The Cronbach's α coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.890.

Suicide behavior questionnaire: The questionnaire consists of 3 items to assess an individual's suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicidal behavior in the past year. Each entry is scored from "never = 0" to "often = 3" for a total score ranging from 0-9, with a score of > 0 being considered at risk of suicide. The Cronbach's α coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.910[10].

The researchers randomly selected 30 nurses in a tertiary hospital in Jiangxi Province to conduct a presurvey and consulted relevant experts to modify the questionnaire according to feedback from the presurvey. The researchers contacted the person in charge of the hospitals in each province and explained to this person the purpose of this study and the principle of voluntary participation. Nurses who met the inclusion criteria were informed of the significance of the study, the precautions for questionnaire completion, etc., and the questionnaires were distributed after nurses provided informed consent. The questionnaire used a unified guideline and assessment tool, and the authenticity of the data collection was emphasized during the study.

The data were statistically analyzed via SPSS 25.0 software. Measures conforming to a normal distribution are expressed as (mean ± SD), nonnormally distributed measures are expressed as M (P25, P75), and count data are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Univariate analysis of differences in suicide risk among nurses across demographics was performed. Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore the correlation between the variables, the PROCESS 4.0 program was used for mediation effect analysis, and the bootstrap method was used to test the mediation effect model.

A total of 750 nurses were included in the survey, of whom 244 (32.5%) were male and 506 (67.5%) were female. These nurses were predominantly 26-35 years old (63.9%), had a bachelor's degree (83.5%), and had worked for more than 10 years (41.3%). They predominantly worked 6-10 night shifts per month (54.5%) and generally worked more than 8 hours per day (80.7%). Most of the nurses in this study had no children (40.8%) and had a 15-30 minutes commute to work (44.8%). The specific sociodemographic data are shown in Table 1. Comparisons were conducted with the suicide risk score as the dependent variable and nurses' sociodemographic information as the independent variable. The results revealed statistically significant differences in the suicide risk scores of nurses by age, number of night shifts, daily working hours, number of children, and province (P < 0.05; Table 1).

| Variables | Type | Value | Score (mean ± SD) | t/F | P value |

| Sex | Male | 244 (32.5) | 2.20 ± 2.37 | 1.56 | 0.120 |

| Female | 506 (67.5) | 1.92 ± 2.11 | |||

| Age (years) | ≤ 25 | 94 (12.5) | 2.11 ± 2.27 | 3.702 | 0.012 |

| 26-35 | 479 (63.9) | 2.13 ± 2.25 | |||

| 36-45 | 141 (18.8) | 1.82 ± 2.03 | |||

| > 45 | 36 (4.8) | 0.94 ± 1.57 | |||

| Educational level | Associate degree | 113 (15.1) | 2.12 ± 2.21 | 0.403 | 0.669 |

| Bachelor degree | 626 (83.5) | 1.98 ± 2.20 | |||

| Graduate degree or above | 11 (1.5) | 2.45 ± 2.16 | |||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 238 (31.7) | 2.15 ± 2.16 | 1.119 | 0.327 |

| Married | 499 (66.5) | 1.96 ± 2.23 | |||

| Divorce or widow | 13 (1.7) | 1.38 ± 1.56 | |||

| Years of work | < 1 | 15 (2.0) | 1.80 ± 1.86 | 2.526 | 0.056 |

| 1-5 | 232 (30.9) | 2.33 ± 2.30 | |||

| 6-10 | 193 (25.7) | 1.93 ± 2.20 | |||

| > 10 | 310 (41.3) | 1.83 ± 2.11 | |||

| Title | Junior nurse | 118 (15.7) | 1.85 ± 1.99 | 0.941 | 0.420 |

| Intermediate nurse | 312 (41.6) | 2.13 ± 2.31 | |||

| Nurse-in-charge | 283 (37.7) | 2.00 ± 2.19 | |||

| Senior nurse | 37 (4.9) | 1.59 ± 1.86 | |||

| Monthly income (CNY) | < 5000 | 101 (13.5) | 2.23 ± 2.32 | 1.234 | 0.292 |

| 5000-10000 | 562 (74.9) | 2.01 ± 2.22 | |||

| > 10000 | 87 (11.6) | 1.72 ± 1.90 | |||

| Number of night shifts (per month) | 0 | 80 (10.7) | 1.44 ± 1.98 | 6.619 | < 0.001 |

| 1-5 | 201 (26.8) | 1.99 ± 2.09 | |||

| 6-10 | 409 (54.5) | 1.98 ± 2.14 | |||

| > 10 | 60 (8.0) | 3.07 ± 2.85 | |||

| Daily working hours (hours) | ≤ 8 | 145 (19.3) | 1.57 ± 2.00 | -2.719 | 0.007 |

| > 8 | 605 (80.7) | 2.12 ± 2.23 | |||

| Number of children | 0 | 306 (40.8) | 2.21 ± 2.23 | 3.669 | 0.026 |

| 1 | 257 (34.3) | 1.72 ± 2.13 | |||

| 2 | 187 (24.9) | 2.09 ± 2.20 | |||

| ≥ 3 | 0 (0) | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |||

| Commuting time to work (minutes) | < 15 | 133 (17.7) | 1.88 ± 2.15 | 0.490 | 0.689 |

| 15-30 | 336 (44.8) | 2.11 ± 2.21 | |||

| 31-60 | 207 (27.6) | 1.99 ± 2.29 | |||

| > 60 | 74 (9.9) | 1.86 ± 1.96 | |||

| Department | Internal Medicine | 166 (22.1) | 2.04 ± 2.28 | 0.759 | 0.552 |

| Surgery | 169 (22.5) | 2.17 ± 2.31 | |||

| Pediatrics | 131 (17.5) | 1.78 ± 2.10 | |||

| Gynecology | 137 (18.3) | 1.89 ± 2.07 | |||

| Other departments (emergency, ICU, etc.) | 147 (19.6) | 2.11 ± 2.19 | |||

| Province | Jiangxi | 140 (18.7) | 1.92 ± 2.01 | 5.861 | < 0.001 |

| Sichuan | 119 (15.9) | 2.29 ± 2.14 | |||

| Shaanxi | 120 (16.0) | 2.54 ± 2.68 | |||

| Zhejiang | 120 (16.0) | 2.38 ± 2.28 | |||

| Shanxi | 120 (16.0) | 1.68 ± 2.00 | |||

| Guangdong | 131 (17.5) | 1.32 ± 1.82 |

The present study revealed that nurses had a total WFBRC score of 59.00 (49.75, 67.00), a daytime sleepiness score of 21.00 (17.00, 24.00), and a suicide risk score of 2.00 (0.00, 3.00), as shown in Table 2.

| Item | Score | Average score of items |

| Work-family behavioral role conflict | 59.00 (49.75, 67.00) | 3.11 (2.62, 3.53) |

| The impact of work on family | 25.00 (22.00, 28.00) | 3.57 (3.14, 4.00) |

| The impact of family on work | 34.00 (26.00, 40.00) | 2.83 (2.17, 3.33) |

| Daytime sleepiness | 21.00 (17.00, 24.00) | 3.00 (2.43, 3.43) |

| Suicide risk | 2.00 (0.00, 3.00) | 0.67 (0.00, 1.00) |

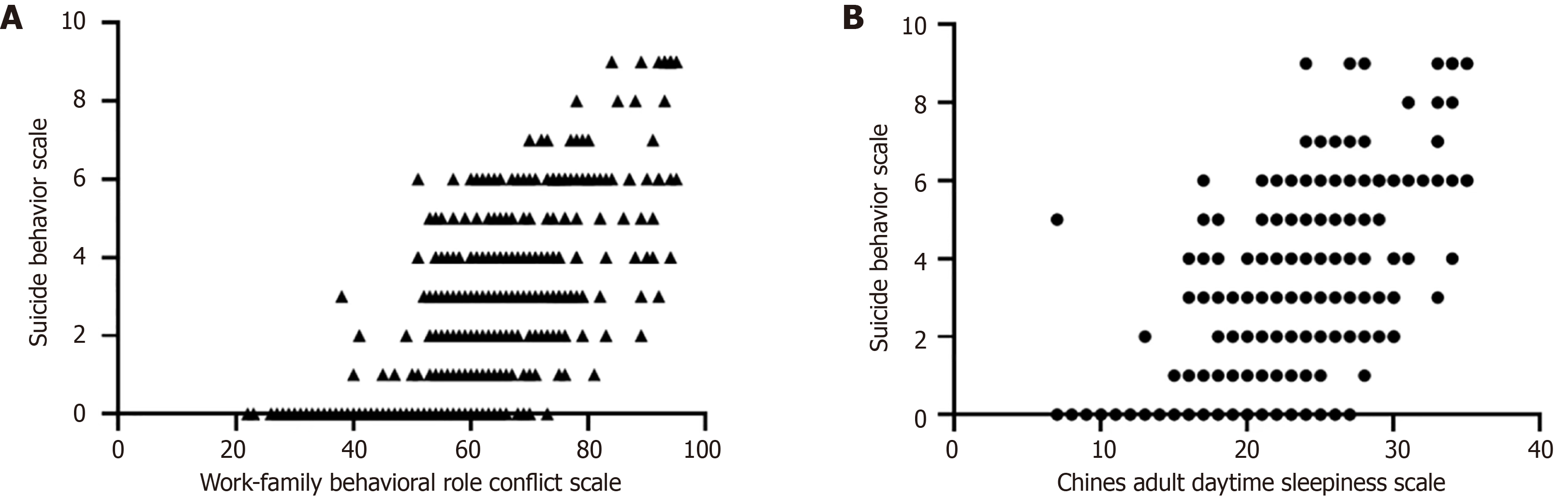

The results of the correlation analysis revealed that WFBRC was positively correlated with the risk of suicide (r = 0.734, P < 0.01) and that daytime sleepiness was positively correlated with the risk of suicide (r = 0.717, P < 0.01). The correlations between specific variables are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

| Item | Work-family behavioral role conflict | The impact of work on family | The impact of family on work | Daytime sleepiness | Suicide risk |

| Work-family behavioral role conflict | 1 | ||||

| The impact of work on family | 0.816a | 1 | |||

| The impact of family on work | 0.953a | 0.603a | 1 | ||

| Daytime sleepiness | 0.817a | 0.653a | 0.785a | 1 | |

| Suicide risk | 0.734a | 0.536a | 0.733a | 0.717a | 1 |

The mediating role of daytime sleepiness between WFBRC and suicide risk was tested via the PROCESS 4.0 program in SPSS software. The results revealed a significant positive effect of WFBRC on suicide risk (β = 0.118, P < 0.001) and daytime sleepiness (β = 0.304, P < 0.001) and a significant positive effect of daytime sleepiness on suicide risk (β = 0.152, P < 0.001). A further mediation effect test was conducted via the bootstrap method, which revealed that the indirect effect of WFBRC on suicide risk, i.e., the mediating effect of daytime sleepiness, was significant (P < 0.001), the direct effect was significant (P < 0.001), and the total effect was significant (P < 0.001); i.e., the model was a partially mediated model, with a mediation effect value of 0.046, and the effect accounted for 38.98%. Thus, WFBRC not only has a significant direct effect on suicide risk but can also have a significant indirect effect on suicide risk through daytime sleepiness. These results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

| Independent variable | Dependent variable | t | β | SE | P value |

| Work-family behavioral role conflict | Suicide risk | 29.561 | 0.118 | 0.004 | < 0.001 |

| Work-family behavioral role conflict | Daytime sleepiness | 38.686 | 0.304 | 0.008 | < 0.001 |

| Work-family behavioral role conflict | Suicide risk | 10.878 | 0.072 | 0.007 | < 0.001 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 8.564 | 0.152 | 0.018 | < 0.001 |

| Path | Effect relationship | Effect value | 95%CI | P value | Effect proportion (%) | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Work-family behavioral role conflict → suicide risk | Total effect | 0.118 | 0.110 | 0.126 | < 0.001 | |

| Work-family behavioral role conflict → suicide risk | Indirect effects | 0.046 | 0.033 | 0.060 | < 0.001 | 38.98 |

| Work-family behavioral role conflict → suicide risk | Direct effects | 0.072 | 0.059 | 0.085 | < 0.001 | 61.01 |

Nurses' WFBRC score in this study was 59.00 (49.75, 67.00), which is moderate and lower than the results of Sun et al's survey[11] of nurses' WFBRC (75.70 ± 17.62). This difference may be because the study subjects were located in different provinces. Sun et al[11] surveyed 994 nurses in a tertiary hospital in Shanghai. Shanghai is the financial center of China, with a developed and competitive economy and an extremely fast pace of work and life; thus, nurses there have higher levels of WFBRC. In addition, the two studies included different sample sizes, and there were individual differences in the survey respondents, which, in turn, affected the findings. Therefore, future researchers should increase the sample size, expand the scope of the survey, and conduct longitudinal studies to maintain the reliability and stability of the findings. In addition, this study further illustrates the high level of role conflict in nurses' work-family behaviors, which is generally consistent with the findings of El Keshky and Sarour[12]. Therefore, it is recommended that nursing administrators encourage nurses to express their needs to develop appropriate strategic support for work and family[6]. Nurses' daytime sleepiness score in this study was 21.00 (17.00, 24.00), which was moderate and was consistent with the findings of Westwell et al[13] and Chen et al[6]. This moderate score may be due to the heavy nursing workload and frequent night shifts, which, consequently, make nurses more prone to daytime sleepiness symptoms. In addition, studies have shown a high incidence of daytime sleepiness among nurses[6,14]. Considering the impact of daytime sleepiness on nurses' work and patient safety, it is recommended that nursing administrators rationalize rest arrangements for nurses after long hours of work or night shifts to alleviate symptoms such as daytime sleepiness. The suicide risk score of nurses in this study was 2.00 (0.00, 3.00), which was higher than that of the general population[15]. The reason for this may be related to the nature of nursing work, which is characterized by long working hours and high pressure, making nursing staff prone to negative emotions and suicidal thoughts. In addition, when nursing staff are unable to find a balance in the face of work-family conflicts, they are prone to frustration and a sense of powerlessness, which may also lead to suicidal ideation[3]. It is recommended that nursing administrators pay close attention to the mental health of nurses, appropriately increase the number of staff in units, and avoid having nurses work under prolonged high pressure to reduce the risk of suicide among nurses.

The results of this study revealed a positive correlation between nurses' WFBRC and suicide risk, i.e., the higher the level of nurses' WFBRC was, the greater their suicide risk. The reason for this finding may be that when individuals experience work-family conflict, they tend to perceive a low quality of family life and happiness, which in turn affects the quality of their marriage and creates negative emotions that can easily lead to suicidal thoughts[3]. Moreover, the results of this study revealed that nurses' WFBRC was positively correlated with daytime sleepiness; that is, the higher the level of nurses' WFBRC was, the greater the level of their daytime sleepiness. This finding may be because the nursing profession is predominantly female, and women must bear not only the pressure of work but also the responsibility of raising children and taking care of the family, which may lead to a decrease in the normal sleep time of nursing staff and increase the occurrence of daytime sleepiness[16]. In addition, the results of this study revealed that daytime sleepiness was positively correlated with suicide risk, i.e., the higher the level of daytime sleepiness was, the greater the suicide risk. The reason for this finding may be that nurses with daytime sleepiness are more likely to feel fatigued and experience somatic disorders[5], and individuals with daytime sleepiness are more likely to experience severe depression and anxiety than those without daytime sleepiness, which, in turn, increases the risk of suicide[17]. Therefore, it is reco

The results of this study revealed that WFBRC had a positive predictive effect on suicide risk; that is, the greater the level of WFBRC was, the greater the stress nurses faced and the greater the likelihood that they would develop psychological problems that can lead to suicidal ideation[18]. The results of this study showed that daytime sleepiness partially mediated the relationship between nurses’ WFBRC and suicide risk, with a mediation effect value of 0.046 and a mediation effect percentage of 38.98%. These findings suggest that the level of WFBRC can directly affect suicide risk or indirectly affect suicide risk through daytime sleepiness. The reason for this effect may be that when the level of WFBRC is high, nurses facing double pressure from work and family may allocate less time for normal sleep and recovery from fatigue and are more prone to daytime sleepiness[6], which can lead to disruption of the individual's sleep cycle; moreover, the decline in nurses' quality of sleep further mediates the onset of negative emotions[19], which increases the risk of suicide in nurses[20]. Nurses are the main providers of medical services and bear the responsibility of protecting patients' physical health; thus, nurses’ physical and mental health should be emphasized by hospital administrators. Therefore, hospital administrators should optimize workflows, improve work efficiency, pay attention to sleep hygiene education issues, conduct regular mental health screenings for nursing staff, and strengthen humanistic care and emotional support to reduce nurses’ risk of suicide.

First, this study was a multicenter survey that generated highly generalizable findings. Second, this study analyzed the relationships between nurses' WFBRC and daytime sleepiness and suicide risk, which provides a reference basis for developing strategies to improve nurses' mental health worldwide. Finally, the entire process of this study was rigorous and scientific, and the analysis was conducted by strictly following statistical methods and increasing the sample size to reduce measurement error. Nevertheless, there are several shortcomings in this study. First, the scale used in this study, although it has been successfully used in related studies, may be subjective in measurement, and future studies could adopt a longitudinal design to allow for more comprehensive observation and analysis and incorporate qualitative research to gain insight into nurses' experiences and feelings. Second, this study, as a cross-sectional study, was unable to draw causal inferences. Finally, the population of this study was a group of nurses, and thus, its findings may be inconsistent across populations; further research could be conducted in the future to verify the applicability of the findings to other populations.

Through analysis, this study revealed that: (1) Chinese nurses' WFBRC and daytime sleepiness were both positively associated with suicide risk; (2) WFBRC and daytime sleepiness were positively predictive of suicide risk; and (3) Daytime sleepiness mediated the relationship between WFBRC and suicide risk among Chinese nurses. In the future, nursing managers should take effective measures to alleviate nurses' WFBRC, such as reducing work hours and workload and developing appropriate work or family support strategies, which will in turn alleviate nurses' daytime sleepiness and other symptoms, thus effectively reducing their suicide risk. Nurses themselves should clarify their role positioning, manage their time effectively, improve work efficiency, and prevent suicidal ideation.

All authors extend their sincerest thanks to the editors and reviewers for improving the quality of the manuscript.

| 1. | Knipe D, Padmanathan P, Newton-Howes G, Chan LF, Kapur N. Suicide and self-harm. Lancet. 2022;399:1903-1916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 50.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang ZH, Wang XT. [The sex ratio of suicide risk in China: Relevant theories, risk factors, coping strategies and social expectancy for stress coping]. Xinli Kexue Jinzhan. 2023;31:2155-2170. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Ding Y, Sun R, Gui Z, Wang K, Li X. [Association of work-family conflict with suicidal ideation among medical staff: a cross-sectional survey in Shandong province]. Zhongguo Gonggong Weisheng. 2023;39:1250-1254. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Sun WL, Wu Y, Gao J, Guo CY. [Reliability and validity of Chinese version of the Work-Family Behavioral Role Conflict Scale]. Zhonghua Huli Zazhi. 2023;58:1787-1793. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Dong QY, Yang XF, Liu BP, Zhang YY, Wan LP, Jia CX. Menstrual pain mediated the association between daytime sleepiness and suicidal risk: A prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2023;328:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen SS, Shen ZQ, Chen FF, Zhang QX, Wei Q, Sun CX. [Latent class analysis of daytime sleepiness among nurses working rotating shifts in intensive care units: the influencing factors]. Hulixue Zazhi. 2023;38:63-72. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Li K, He J. [Medical statistics]. 6th ed. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House, 2013. |

| 8. | Zhang YQ. [Revision and application of the Simplified Work-Family Behavior Role Conflict Scale]. MSc Thesis, Guizhou Normal University. 2023. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Wang D, Chen H, Chen D, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Wang T, Yu Q, Jiang J, Chen Z, Li F, Zhao L, Fan F, Liu X. Shift work disorder and related influential factors among shift workers in China. Sleep Med. 2021;81:451-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Wen Y, He MN, Wu HX, Li GY, Guo N, Wu DX. [Job-Hunting Stress and Suicide Risk of Graduates: A Moderated Mediating Model]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi. 2024;32:441-445. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Sun WL, Wu Y, Zhang Q, Wang XX, Guo CY, Gao J. [Current situation and influencing factors of work-family behavioral role conflict in nurses]. Hushi Jinxiu Zazhi. 2024;39:529-533. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | El Keshky MES, Sarour EO. The relationships between work-family conflict and life satisfaction and happiness among nurses: a moderated mediation model of gratitude and self-compassion. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1340074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Westwell A, Cocco P, Van Tongeren M, Murphy E. Sleepiness and safety at work among night shift NHS nurses. Occup Med (Lond). 2021;71:439-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mori M, Krumholz HM, Allore HG. Using Latent Class Analysis to Identify Hidden Clinical Phenotypes. JAMA. 2020;324:700-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Haregu T, Cho E, Spittal M, Armstrong G. The rate of transition to a suicide attempt among people with suicidal thoughts in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023;331:57-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Arbour M, Tanner T, Hensley J, Beardsley J, Wika J, Garvan C. Factors That Contribute to Excessive Sleepiness in Midwives Practicing in the United States. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64:179-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shen Y, Meng F, Tan SN, Zhang Y, Anderiescu EC, Abeysekera RE, Luo X, Zhang XY. Excessive daytime sleepiness in medical students of Hunan province: Prevalence, correlates, and its relationship with suicidal behaviors. J Affect Disord. 2019;255:90-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li Y, Fan R, Lu Y, Li H, Liu X, Kong G, Wang J, Yang F, Zhou J, Wang J. Prevalence of psychological symptoms and associated risk factors among nurses in 30 provinces during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;30:100618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maruani J, Molière F, Godin O, Yrondi A, Bennabi D, Richieri R, El-Hage W, Allauze E, Anguill L, Bouvard A, Camus V, Dorey JM, Etain B, Fond G, Genty JB, Haffen E, Holtzmann J, Horn M, Kazour F, Nguon AS, Petrucci J, Rey R, Stephan F, Vaiva G, Walter M; FondaMental Advanced Centers of Expertise in Resistant Depression (FACE-DR) Collaborators, Lejoyeux M, Leboyer M, Llorca PM, Courtet P, Aouizerate B, Geoffroy PA. Diurnal symptoms of sleepiness and dysfunction predict future suicidal ideation in a French cohort of outpatients (FACE-DR) with treatment resistant depression: A 1-year prospective study about sleep markers. J Affect Disord. 2023;329:369-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chan NY, Zhang J, Tsang CC, Li AM, Chan JWY, Wing YK, Li SX. The associations of insomnia symptoms and chronotype with daytime sleepiness, mood symptoms and suicide risk in adolescents. Sleep Med. 2020;74:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/