Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111761

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 104 Days and 1.6 Hours

Anxiety and depression are highly prevalent among patients with cervical cancer (CC). However, few studies have systematically analyzed the psychological effects of tumor stage, treatment methods, and related factors on these patients, or developed predictive models for these outcomes.

To identify factors influencing anxiety and depression in patients with CC and construct predictive models.

We retrospectively analyzed data from 119 patients with CC treated at the Gyne

During treatment, 64.71% of the patients experienced anxiety and 52.10% ex

Family income, tumor stage, treatment method, and hope level are key determinants of anxiety and depression in patients with CC. Predictive models incorporating these factors can effectively assess risk of anxiety and dep

Core Tip: Cervical cancer (CC) causes long-term distress in women, who are prone to negative emotions such as anxiety and depression. This study analyzed the factors influencing anxiety and depression in patients with CC and developed a predictive model. The findings provide guidance for the clinical assessment of psychological risks and support the adoption of targeted measures to reduce these risks.

- Citation: Xie ZJ, Zhang H, Ma RY, Su HL. Influencing factors and predictive model construction of anxiety and depression in patients with cervical cancer. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 111761

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/111761.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111761

Cervical cancer (CC) is a malignant tumor of the cervix, vagina, and cervical canal and remains the most common malignancy of the female reproductive system[1]. Common clinical symptoms include vaginal bleeding, discharge, pain, urinary frequency or urgency, and constipation[2]. Standard treatments include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy[3]. However, patients often face the psychological burden of diagnosis, while surgery may involve hysterectomy and radiotherapy or chemotherapy can cause adverse effects such as vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, and hair loss. This challenges contribute to varying degrees of anxiety and depression, which may significantly affect prognosis[4]. In addition, as CC is strongly associated with human papillomavirus infection[5], some patients may feel shame or stigma, believing the disease to be linked to sexual behavior, which further increases anxiety and depression.

Anxiety is characterized by excessive worry, fear, or tension about potential threats, often accompanied by hy

We retrospectively collected data from 119 patients with CC who received treatment in the Gynecology Department of Suzhou Ninth People’s Hospital between January 2017 and May 2025.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Met the diagnostic criteria for CC as stipulated in the guidelines[8] and confirmed via pathological examination; (2) Age ≥ 18 years; (3) No major family stress events occurred during diagnosis or treatment; and (4) Completed a hope scale assessment at diagnosis and underwent anxiety and depression scale assessments during treatment.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of tumors at sites other than CC; (2) Severe cardiac, hepatic, or renal dysfunction; (3) Language or communication disorders; (4) Pre-existing psychiatric disorder before CC diagnosis; and (5) Incomplete medical records.

The Ethics Committee of Suzhou Ninth Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (Suzhou Ninth People’s Hospital) approved this study.

Data collection: Patients data were obtained from the hospital information system, including electronic medical records, pathology reports, treatment records, and questionnaire assessments. The following data were collected: Age, residence, marital status, education level, monthly family income, comorbidities (e.g., hypertension and diabetes), tumor stage, tumor pathology type, and treatment method.

Hope level assessment: Hope levels were assessed at diagnosis using the Brief Hope Measurement Instrument developed by Herth[9]. The scale comprises 12 items across three dimensions: Reality orientation, positive action, and interpersonal closeness. Each item was scored on a 4-point scale (1-4), with a total score of 12-48. Scores of 12-23 indicated low hope, 24-35 indicated medium hope, and 36-48 indicated high hope.

Anxiety and depression assessment: Anxiety was assessed using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), which consists of 20 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Fifteen items were score positively and five negatively scored. The raw total score was multiplied by 1.25 to obtain the standard score. A standard score < 50 indicated no anxiety; 50-59 mild; 60-69 moderate; and ≥ severe anxiety[10]. Depression was assessed using the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), also with 20 items (10 positive, 10 negative). The standard scores were derived in the same manner as for anxiety. A score < 53 indicated no depression; 53-62 mild; 63-72 moderate; and ≥ 73 severe depression[11].

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0. Categorical data are expressed as n (%), with groups compared using the χ2 test. Factors influencing anxiety and depression in the patients were explored using multivariate logistic regression to construct predictive model formulas. Model performance was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). Goodness-of-fit was assessed with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test to exclude overfitting. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The SAS scale assessment showed that the incidence of anxiety during treatment among the 119 patients with CC was 64.71% (77/119). The SDS scale assessment indicated that the incidence of depression was 52.10% (62/119). Analysis revealed significant differences in family monthly income, tumor stage, treatment modality, and hope level between CC patients with and without anxiety or depression (P < 0.05; Table 1).

| Characteristics | Total | Anxiety assessment | Depression assessment | ||||||

| Has anxiety | No anxiety | χ2 | P value | Has depression | No depression | χ2 | P value | ||

| Age (years) | 2.747 | 0.097 | 1.780 | 0.182 | |||||

| < 60 | 66 | 47 (61.04) | 19 (45.24) | 38 (61.29) | 28 (59.12) | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 53 | 30 (38.96) | 23 (54.76) | 24 (38.71) | 29 (50.88) | ||||

| Place of residence | 0.135 | 0.713 | 0.555 | 0.456 | |||||

| Town/city | 48 | 32 (41.56) | 16 (38.10) | 27 (43.55) | 21 (36.84) | ||||

| Rural area | 71 | 45 (58.44) | 26 (61.90) | 35 (56.45) | 36 (63.16) | ||||

| Marital status | 1.116 | 0.291 | 1.603 | 0.206 | |||||

| Married | 99 | 62 (80.52) | 37 (88.10) | 49 (79.03) | 50 (87.72) | ||||

| Unmarried or divorced | 20 | 15 (19.48) | 5 (11.90) | 13 (20.97) | 7 (12.28) | ||||

| Educational level | 0.093 | 0.760 | 0.018 | 0.892 | |||||

| High school and below | 87 | 57 (74.03) | 30 (71.43) | 45 (72.58) | 42 (73.68) | ||||

| College degree or above | 32 | 20 (25.97) | 12 (28.57) | 17 (27.42) | 15 (26.32) | ||||

| Monthly family income | 7.661 | 0.022 | 6.849 | 0.033 | |||||

| < 5000 yuan (RMB) | 38 | 30 (38.96) | 8 (19.05) | 26 (41.94) | 12 (21.05) | ||||

| 5000-8000 yuan (RMB) | 54 | 28 (36.36) | 26 (61.90) | 22 (35.48) | 32 (56.14) | ||||

| > 8000 yuan (RMB) | 27 | 19 (24.68) | 8 (19.05) | 14 (22.58) | 13 (22.81) | ||||

| Underlying disease | 2.753 | 0.097 | 1.303 | 0.254 | |||||

| Have | 24 | 19 (24.68) | 5 (11.90) | 15 (24.19) | 9 (15.79) | ||||

| Not have | 95 | 58 (75.32) | 37 (88.10) | 47 (75.81) | 48 (84.21) | ||||

| Tumor staging | 7.581 | 0.006 | 4.437 | 0.035 | |||||

| Phase I-II | 59 | 31 (40.26) | 28 (66.67) | 25 (40.32) | 34 (59.65) | ||||

| Phase III-IV | 60 | 46 (59.74) | 14 (33.33) | 37 (59.68) | 23 (40.35) | ||||

| Pathological type | 0.627 | 0.731 | 1.370 | 0.504 | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 24 | 14 (18.18) | 10 (23.81) | 10 (16.13) | 14 (24.56) | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 90 | 60 (77.92) | 30 (71.43) | 49 (79.03) | 41 (71.93) | ||||

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 5 | 3 (2.90) | 2 (4.76) | 3 (4.84) | 2 (3.51) | ||||

| Tumor treatment methods | 10.245 | 0.001 | 5.147 | 0.023 | |||||

| Monotherapy1 | 40 | 18 (23.38) | 22 (52.38) | 15 (24.19) | 25 (43.86) | ||||

| Combined treatment2 | 79 | 59 (76.62) | 20 (47.62) | 47 (75.81) | 32 (56.14) | ||||

| Hope level | 15.139 | 0.001 | 11.783 | 0.003 | |||||

| Low | 50 | 38 (51.95) | 12 (23.81) | 33 (53.22) | 17 (29.83) | ||||

| Medium | 44 | 31 (37.66) | 13 (35.71) | 23 (37.10) | 21 (36.84) | ||||

| High | 25 | 8 (10.39) | 17 (40.48) | 6 (9.68) | 19 (33.33) | ||||

Taking the presence of anxiety or depression during treatment (0 = no; 1 = yes) as the dependent variable, the statistically significant factors from the univariate analysis (family monthly income, tumor stage, treatment method, and hope level) served as independent variables (Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression showed that family monthly income < 5000 yuan (OR = 2.214, P = 0.022), stage III-IV tumor (OR = 1.811, P = 0.013), comprehensive treatment (OR = 2.989, P = 0.006), and low hope level (OR = 3.267, P = 0.001) were risk factors for anxiety (P < 0.05; Table 3). For depression, risk factors included family monthly income < 5000 yuan (OR = 1.540, P = 0.027), stage III-IV tumor (OR = 1.679, P = 0.030), comprehensive treatment (OR = 2.069, P = 0.012), and low hope level (OR = 2.988, P = 0.004) (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Variable | Description of valuation |

| Monthly household income | 0 ≥ 8000 yuan; 1 = 5000-8000 yuan; 2 ≤ 5000 yuan |

| Tumor staging | 0 = phase I-II; 1 = phase III-IV |

| Tumor treatment methods | 0 = monotherapy; 1 = combined treatment |

| Hope level | 0 = high; 1 = medium; 2 = low |

| Variable | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Family monthly income < 5000 yuan | 0.795 | 0.347 | 5.249 | 0.022 | 2.214 (1.122-4.371) |

| Tumor stage III-IV | 0.594 | 0.239 | 6.177 | 0.013 | 1.811 (1.134-2.892) |

| Comprehensive tumor treatment | 1.095 | 0.398 | 7.569 | 0.006 | 2.989 (1.370-6.521) |

| Low hope level | 1.184 | 0.359 | 10.877 | 0.001 | 3.267 (1.616-6.606) |

| Constant term | -9.176 | 2.593 | 12.523 | < 0.001 | - |

| Variable | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Family monthly income < 5000 yuan | 0.432 | 0.195 | 4.908 | 0.027 | 1.540 (1.051-2.257) |

| Tumor stage III-IV | 0.518 | 0.238 | 4.737 | 0.030 | 1.679 (1.053-2.675) |

| Comprehensive tumor treatment | 0.727 | 0.289 | 6.328 | 0.012 | 2.069 (1.175-3.644) |

| Low hope level | 1.095 | 0.380 | 8.303 | 0.004 | 2.988 (1.419-6.297) |

| Constant term | -8.541 | 2.572 | 11.027 | < 0.001 | - |

Based on multivariate analysis, risk prediction equations for anxiety and depression were derived. For anxiety: Logit

The goodness-of-fit deviation test revealed no overfitting (χ2 = 1.875, P > 0.05).

For depression: Logit (P) = 0.432 × family monthly income (0 ≥ 8000 yuan; 1 = 5000-8000 yuan; 2 ≤ 5000 yuan) + 0.518 × tumor stage (0 = I-II stage; 1 = III-IV stage) + 0.727 × treatment method (0 = single; 1 = comprehensive) + 1.095 × hope level (0 = high; 1 = medium; 2 = low) − 8.541.

The goodness-of-fit deviation test also indicated no overfitting (χ2 = 2.073, P > 0.05).

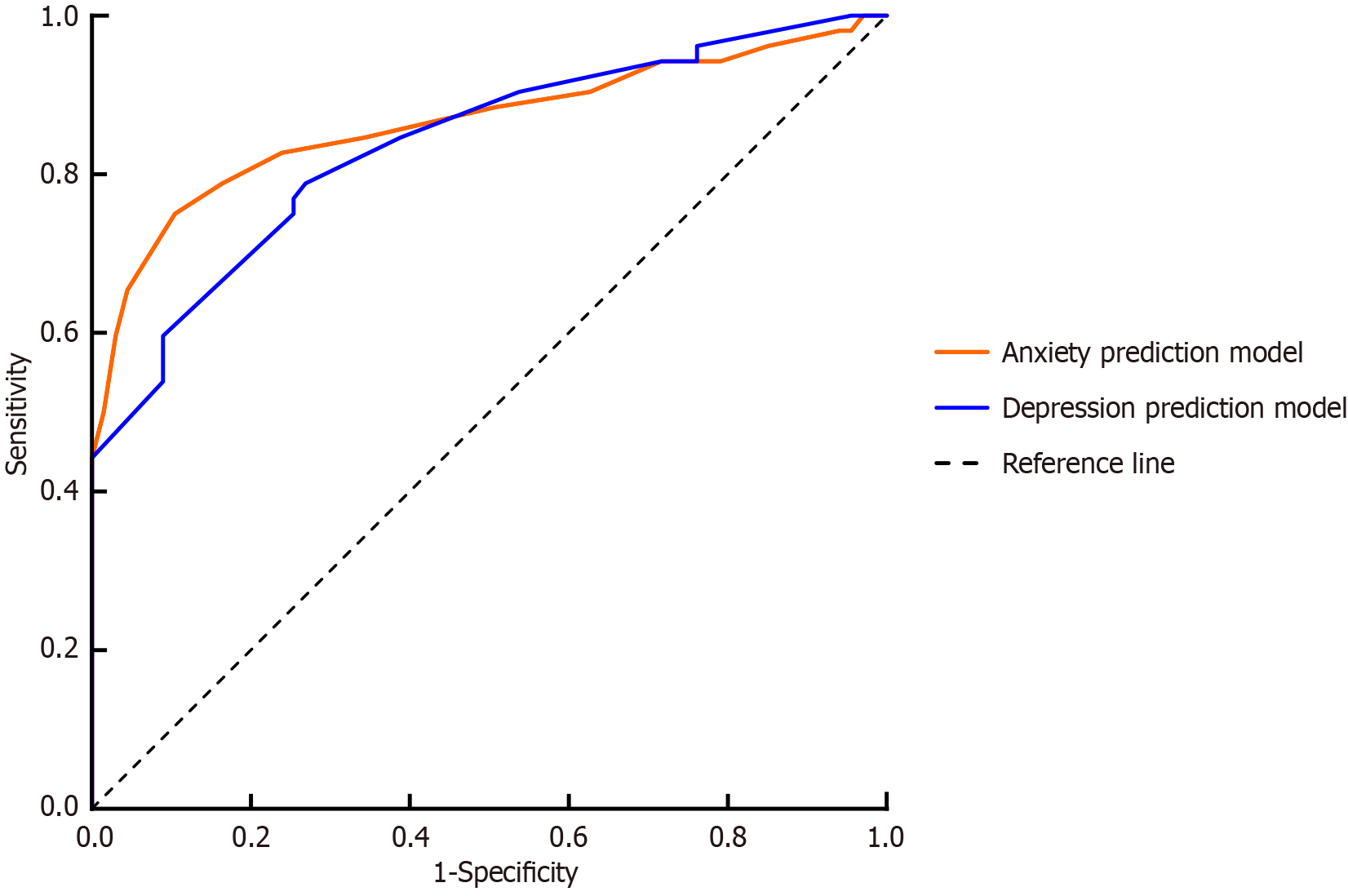

The ROC curve analysis showed an AUC of 0.865 (95%CI: 0.792-0.938) for the anxiety model and 0.837 (95%CI: 0.763-0.911) for the depression model, indicating good discrimination ability (Figure 1).

Cancer treatment is a long process, and patients are often troubled by the disease, making them prone to negative emotions such as anxiety and depression[12]. Thangarajah et al[13] reported that approximately 68.8% of patients with CC experience anxiety, 51.4% worry, and 26.3% panic, indicating that CC has become a significant psychological stressor that contributes to adverse psychological outcomes. In this study of 119 patients with CC, the incidence of anxiety during treatment was 64.71% and that of depression was 52.10%, findings consistent with those of Yang et al[7]. These symptoms may arise because patients with CC fear treatment failure, disease progression, and threats to life. Additionally, disease-related exhaustion and reduced social engagement may lead to feelings of helplessness, alienation from family or friends, and diminished emotional support, thereby contributing to depression and loneliness[14].

Our study identified low family monthly income (< 5000 yuan), stage III-IV tumor, comprehensive treatment, and low hope level as influencing factors for anxiety and depression in patients with CC. The reasons for this may include the following: (1) For low-income families, economic hardship combined with the stress of illness often heightens anxiety and depression, negatively affecting quality of life. Okyere Asante et al[15] similarly found that CC patients with lower income experience greater psychological pressure, supporting our results. Because CC treatment is both prolonged and costly, patients face not only direct medical expenses but also indirect financial losses due to reduced productivity, which further exacerbates psychological distress; and (2) Advanced tumor stage increases the extent of cancer spread, treatment complexity, and uncertainty of prognosis, leading patients to greater anxiety and depression. Tosic Golubovic et al[16] also observed a significant correlation between tumor stage and psychological distress, supporting our findings. Treatment methods (surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy) vary across CC stages, and each can affect patient’s physical and psychological health differently. For example, a total hysterectomy may cause great stress and pain, heightening concerns about postoperative recovery and increasing anxiety and depression[17]. Furthermore, if surgical margins are positive or lymph node metastasis is present, radiotherapy is required to eliminate the residual carcinomas and reduce recurrence risk. However, close-field radiotherapy to the uterine cavity can cause toxic side effects, including radiation cystitis, radiation proctitis, and urinary organ changes, which may further increase patient’s pain and anxiety[18]. For patients unable to undergo surgical intervention, chemotherapy can inhibit the spread of cancer cells, but the drugs often cause nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. These physical discomforts directly affect patients’ mental state, increasing anxiety and depression[19]. This study also found that comprehensive tumor treatment was a factor influencing anxiety and depression in patients with CC. The likely reason is that combining multiple treatments produces cumulative side effects, which significantly affect patients during therapy. Consequently, CC patients receiving comprehensive treatment are more likely to experience anxiety and depression compared with those undergoing a single treatment. Chen and Bai[20] similarly reported that CC patients receiving combined treatment were more prone to psychological distress, indirectly supporting our results. Hope, as a belief, enables patients to maintain a positive outlook on the future and adjust their mindset to accept illness[21]. Patients with higher hope levels tend to believe more in the possibility of a cure, actively adapt their goals to their circumstances, and reduce the occurrence of negative emotions. Li et al[22] found that hope level correlated negatively with the negative emotional expression in CC patients-that is, higher hope corresponded with fewer negative emotions. Conversely, lower hope often results in pessimism, which promotes anxiety and depression. Therefore, in clinical practice, measures should be taken to enhance patients’ hope index, enabling them to better adapt to the disease and reduce negative emotions.

After CC diagnosis, many factors influence patients’ anxiety and depression during treatment, making the construction of an effective prediction model essential. In this study, multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify influencing factors, and predictive models for anxiety and depression in patients with CC were established from the regression coefficients and constant terms of each variable. ROC curve analysis and goodness-of-fit tests demonstrated high diagnostic efficacy. This may be because the study applied independent sample verification, which filtered out irrelevant or weakly related indicators, thereby reducing noise, while integrating multiple related indicators to provide complementary information and improve diagnostic performance.

The limitations of this study are as follows: (1) It retrospectively collected the data of patients with CC from a single center with a relatively small sample size, limiting representativeness; and (2) The prediction model has not undergone external validation, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Future prospective and large-scale studies with external model validation are therefore required.

Low family income, advanced tumor stage, comprehensive treatment, and low hope level correlated positively with anxiety and depression in patients with CC. Constructing a predictive model based on these factors can effectively assess the risk of anxiety and depression and has guiding significance for clinical interventions aimed at reducing their incidence.

| 1. | Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S, Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N, Chen W. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:584-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1790] [Cited by in RCA: 2503] [Article Influence: 625.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Wang L, Wang Y, Yang K, Hu X, Ye G. Roles of microRNA-486-5p in the diagnosis and the association with clinical symptoms of cervical cancer. Biomark Med. 2024;18:869-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, Bradley K, Campos SM, Cho KR, Chon HS, Chu C, Clark R, Cohn D, Crispens MA, Damast S, Dorigo O, Eifel PJ, Fisher CM, Frederick P, Gaffney DK, Han E, Huh WK, Lurain JR, Mariani A, Mutch D, Nagel C, Nekhlyudov L, Fader AN, Remmenga SW, Reynolds RK, Tillmanns T, Ueda S, Wyse E, Yashar CM, McMillian NR, Scavone JL. Cervical Cancer, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:64-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 745] [Article Influence: 124.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bortolato B, Hyphantis TN, Valpione S, Perini G, Maes M, Morris G, Kubera M, Köhler CA, Fernandes BS, Stubbs B, Pavlidis N, Carvalho AF. Depression in cancer: The many biobehavioral pathways driving tumor progression. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:58-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ili C, Lopez J, Buchegger K, Riquelme I, Retamal J, Zanella L, Mora-Lagos B, Vivallo C, Roa JC, Brebi P. Loss of ZNF516 protein expression is related with HR-HPV infection and cervical preneoplastic lesions. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299:1099-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang YL, Liu L, Wang Y, Wu H, Yang XS, Wang JN, Wang L. The prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang YL, Liu L, Wang XX, Wang Y, Wang L. Prevalence and associated positive psychological variables of depression and anxiety among Chinese cervical cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, McCormack M, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv72-iv83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17:1251-1259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 614] [Cited by in RCA: 689] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2251] [Cited by in RCA: 2944] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | ZUNG WW. A SELF-RATING DEPRESSION SCALE. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5900] [Cited by in RCA: 6288] [Article Influence: 209.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Blinderman CD. Psycho-existential distress in cancer patients: A return to "entheogens". J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1205-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thangarajah F, Einzmann T, Bergauer F, Patzke J, Schmidt-Petruschkat S, Theune M, Engel K, Puppe J, Richters L, Mallmann P, Kirn V. Cervical screening program and the psychological impact of an abnormal Pap smear: a self-assessment questionnaire study of 590 patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:391-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Karawekpanyawong N, Kaewkitikul K, Maneeton B, Maneeton N, Siriaree S. The prevalence of depressive disorder and its association in Thai cervical cancer patients. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0252779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Okyere Asante PG, Owusu AY, Oppong JR, Amegah KE, Nketiah-Amponsah E. The psychosocial burden of women seeking treatment for breast and cervical cancers in Ghana's major cancer hospitals. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0289055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tosic Golubovic S, Binic I, Krtinic D, Djordjevic V, Conic I, Gugleta U, Andjelkovic Apostolovic M, Stanojevic M, Kostic J. Risk Factors and Predictive Value of Depression and Anxiety in Cervical Cancer Patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yang X, Huang L, Li C, Ji N, Zhu H. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on alleviating anxiety and depression in postoperative patients with cervical cancer: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e28706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Faravel K, Demontoy S, Jarlier M, De-Meric-de-Bellefon M, Cantaloube M, Laboureur E, Meignant L, Del Rio M, Guerdoux E. Impact of an educational physiotherapy-yoga intervention on perceived stress in women treated with brachytherapy for cervical cancer: a randomised controlled mixed study protocol (KYOCOL). BMJ Open. 2025;15:e098570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nie X. Effects of Network-based Positive Psychological Nursing Model on Negative Emotions, Cancer-related Fatigue, and Quality of Life in Cervical Cancer Patients with Post-operative Chemotherapy. Ann Ital Chir. 2024;95:542-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen J, Bai H. Evaluation of Implementation Effect of Cervical Cancer Comprehensive Treatment Patients With Whole-Course High-Quality Care Combined With Network Continuation Care. Front Surg. 2022;9:838848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yadav S. Perceived social support, hope, and quality of life of persons living with HIV/AIDS: a case study from Nepal. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:157-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li LR, Lin MG, Liang J, Hu QY, Chen D, Lan MY, Liang WQ, Zeng YT, Wang T, Fu GF. Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors on the Level of Hope and Psychological Health Status of Patients with Cervical Cancer During Radiotherapy. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:3508-3517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/