Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111721

Revised: August 28, 2025

Accepted: September 22, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 128 Days and 1.3 Hours

Ovarian cancer patients often face complex treatment processes and psychological challenges, with different treatment modalities potentially affecting patients’ psychological adjustment abilities.

To explore the differences in psychological adjustment patterns among ovarian cancer patients receiving surgery, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and combined therapy, and to analyze their relationship with clinical outcomes.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on the clinical data of 286 ovarian cancer patients who received different treatment modalities from January 2020 to December 2023. Patients were divided into surgery group (n = 78), chemotherapy group (n = 65), targeted therapy group (n = 61), and combined therapy group (n = 82). The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, Self-Rating Depression Scale, and Psychological Adjustment to Cancer Scale were used to assess psychological status, while quality of life, treatment adherence, and two-year survival rate data were collec

Patients in the combined therapy group had significantly higher Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (56.3 ± 7.2) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (58.4 ± 6.9) scores than other groups, with the highest incidence of anxiety (58.5%) and depression (62.2%); the targeted therapy group scored highest in the positive coping dimension (28.5 ± 3.6) and had the lowest incidence of anxiety and depression (29.5%/31.1%). Logistic regression analysis showed that positive coping (odds ratio = 2.86, 95% confidence interval: 1.75-4.68) and utilization of social support (odds ratio = 2.13, 95% confidence interval: 1.42-3.56) were protective factors for good treatment adherence. Longitudinal assessment showed that although all patients experienced increased anxiety and depression symptoms at 3 months of treatment, the targeted therapy group and surgery group showed significant improvement at 6 months (P < 0.05), while the combined therapy group showed no significant improvement. Psychological intervention effectively improved patients’ treatment adherence (by 22.7%) and quality of life (by 15.6 points), with the best effect in the combined therapy group (anxiety incidence decreased by 30.5%, P < 0.001).

Different treatment modalities significantly affect the psychological adjustment abilities of ovarian cancer patients, with combined therapy patients facing greater psychological challenges, while targeted therapy patients exhibit healthier psychological adjustment patterns.

Core Tip: Systematic psychological intervention demonstrates substantial clinical benefits, improving treatment adherence by 22.7% and quality of life by 15.6 points, with combined therapy patients showing the greatest response to intervention (30.5% reduction in anxiety incidence). These findings support the implementation of treatment-specific psychological support protocols, with combined therapy patients requiring more intensive and prolonged psychological interventions to optimize clinical outcomes and patient well-being.

- Citation: Wang YL, He Y, Luo QH, Huang K. Psychological adjustment differences in ovarian cancer patients receiving different treatment modalities and their clinical significance. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 111721

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/111721.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111721

Ovarian cancer, one of the deadliest malignancies of the female reproductive system, imposes a severe physical and psychological burden on patients. With the diversification of modern cancer treatment modalities, the impact of different therapeutic approaches on patients’ mental health has become a growing clinical concern. This study aims to explore the differences in psychological adaptation patterns among ovarian cancer patients receiving different treatment modalities and analyze their association with clinical outcomes, providing empirical evidence for the development of individualized psychological intervention strategies[1-3].

The diagnosis and treatment journey of ovarian cancer is challenging. As a “silent killer”, ovarian cancer presents with subtle early symptoms, with approximately 70% of patients diagnosed at advanced stages, a disease characteristic that itself brings tremendous psychological impact. Traditional comprehensive treatment protocols typically include debulking surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy, which, although effective, are often accompanied by severe physical discomfort, loss of fertility, and dramatic lifestyle changes, further exacerbating patients’ psychological burden[4]. In recent years, with the development of precision medicine, targeted agents such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have demonstrated favorable efficacy and lower toxicity in specific populations, bringing new hope to ovarian cancer treatment while potentially altering patients’ disease experience and psychological adaptation process.

Psychological adaptation, as a core mechanism for cancer patients to cope with their disease, has been proven to be closely related to quality of life, treatment adherence, and survival prognosis[5]. Research indicates that 40%-70% of ovarian cancer patients experience varying degrees of anxiety and depression following diagnosis, which not only reduces patients’ quality of life but may also indirectly affect disease prognosis by influencing treatment adherence, immune function, and neuroendocrine regulation[6]. The conceptual model of psychological adaptation has evolved from a unidimensional to a multidimensional approach, with modern psycho-oncology emphasizing that psychological adaptation is a complex dynamic process involving cognitive assessment, emotional regulation, behavioral coping, and social interaction. The three dimensions assessed by the Psychological Adjustment to Cancer Scale (PACS) - positive coping, negative avoidance, and social support utilization - provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the psychological adaptation of cancer patients[7-9].

In the Chinese cultural context, the psychological adaptation of ovarian cancer patients exhibits unique characteristics. Compared to Western societies, there are significant differences in disease attribution, family support patterns, and doctor-patient communication in Chinese traditional culture[10]. The “family-centered” value system views disease as a family rather than an individual burden, potentially enhancing the protective effect of social support; meanwhile, taboos and stigma associated with cancer may lead to concealment of the condition and social isolation. Additionally, the dominant role of family members in treatment decision-making in the Chinese healthcare system, as well as physicians’ cautious approach to disclosing prognostic information, may influence patients’ cognition of the disease and psychological adaptation process[11].

In recent years, evidence-based research has confirmed that interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and supportive psychotherapy (SPT) can effectively improve the psychological status and quality of life of cancer patients[12]. However, existing intervention strategies often adopt a “one-size-fits-all” approach, lacking personalized design for patients with different treatment backgrounds. With the deepening of precision medicine concepts, psychological intervention strategies tailored to patients’ specific treatment modalities have become an important research direction[13-15].

Despite increasing attention to the mental health issues of ovarian cancer patients, systematic studies on the impact of different treatment modalities on psychological adaptation remain relatively scarce, particularly comparative studies between emerging targeted therapies and traditional treatment approaches. Existing research often focuses on psychological status assessment at a single time point or under a single treatment modality, lacking dynamic monitoring and multidimensional analysis of psychological trajectories throughout the treatment course[16-18]. Furthermore, common psychological interventions in clinical practice lack specificity, making it difficult to meet the differentiated needs of patients with various treatment backgrounds.

Through prospective tracking and multidimensional assessment of 286 ovarian cancer patients receiving different treatment modalities, this study aims to reveal the association patterns between treatment modalities and psychological adaptation abilities, analyze the relationship between psychological adaptation and treatment adherence, quality of life, and prognosis, and evaluate the effects of targeted psychological interventions, thereby providing new perspectives and strategies for the comprehensive management of ovarian cancer patients and optimizing overall survival quality and clinical outcomes.

This retrospective study included 286 patients with ovarian cancer who were treated in the Department of Gynecologic Oncology at Taihe Hospital between January 2020 and December 2023. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Taihe Hospital, Shiyan City (Approval No. SY-TY-2022009125), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Female patients aged 18-75 years; (2) Newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer; (3) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0-2; (4) An expected survival time of at least 6 months; and (5) Complete clinical data. Exclusion criteria included: (1) History of other malignancies; (2) Severe dysfunction of vital organs; (3) Diagnosed psychiatric disorders prior to enrollment; (4) Receipt of systematic psychological treatment or psychotropic medications within the past 6 months; and (5) Incomplete clinical records or inability to complete follow-up.

Based on the primary treatment modality received, patients were categorized into four groups: Surgery group (n = 78): Received tumor debulking surgery only; chemotherapy group (n = 65): Received mainly paclitaxel combined with carboplatin; targeted therapy group (n = 61): Received agents such as PARP inhibitors or anti-angiogenic drugs; combined therapy group (n = 82): Received surgery followed by chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy.

This study collected patients’ demographic characteristics (age, education level, marital status, etc.) and clinical characteristics (Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics FIGO stage, pathological type, carbohydrate antigen 125 level, etc.), and used multiple assessment tools for comprehensive evaluation: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS, ≥ 50 points defined as anxiety) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS, ≥ 53 points defined as depression) to assess psychological status; PACS to evaluate three dimensions: Positive coping, negative avoidance, and utilization of social support; quality of life asse

Patients were followed up every 3 months after treatment initiation for at least 24 months, through outpatient review, telephone follow-up, and home visits, with assessments conducted before treatment, during treatment (3rd month), after treatment completion (6th month), and during follow-up period (12th and 24th month). The primary study endpoint was the difference in psychological adjustment status among different treatment groups and the correlation between psychological adjustment ability and quality of life; secondary endpoints included the relationship between treatment adherence and psychological adjustment status, the relationship between two-year survival rate and psychological adjustment status, and the impact of psychological intervention on treatment adherence and quality of life.

The SPSS version 25.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD, and between-group comparisons were conducted using ANOVA count data were expressed as frequency and percentage, using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis was used to evaluate correlations between variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the relationship between psychological adjustment ability and treatment adherence. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to analyze prognostic factors related to survival. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The 286 ovarian cancer patients included in the study had a mean age of 52.7 ± 8.6 years (surgery group 52.1 ± 8.3 years, chemotherapy group 53.4 ± 8.7 years, targeted therapy group 51.9 ± 8.4 years, combined therapy group 53.2 ± 8.9 years), high school and above education accounted for 46.2%-50.8%, marriage rate 83.1%-86.9%, average body mass index 23.5 ± 3.2 kg/m2 (no statistical significance in differences between groups, P = 0.876). Serous carcinoma was the most common pathological type in all groups (70.5%-75.6%), followed by mucinous carcinoma (9.8%-12.3%), endometrioid carcinoma (6.6%-9.2%), and clear cell carcinoma (4.9%-7.7%); moderate to low differentiation proportions were 67.9% in the surgery group, 72.3% in the chemotherapy group, 66.1% in the targeted therapy group, and 75.6% in the combined therapy group (P = 0.127); positive family tumor history proportions were 4.8%-7.7% (P = 0.762); previous surgery history proportions were 23.1%-28.6% (P = 0.549); comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes were present in 27.4%-32.8% (P = 0.385); postmenopausal patients accounted for 62.8%, 64.6%, 61.3%, and 63.4%, respectively (P = 0.875). There were no statistically significant differences in the above baseline characteristics among the four groups (P > 0.05), indicating comparability. However, in terms of FIGO staging, patients in the combined therapy group had a higher tumor burden, with stage III-IV patients accounting for 76.8% (63/82), significantly higher than the surgery group’s 42.3% (33/78), chemo

| Parameters | Surgery group (n = 78) | Chemotherapy group (n = 65) | Targeted therapy group (n = 61) | Combined therapy group (n = 82) | F/χ2 | P value |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 52.1 ± 8.3 | 53.4 ± 8.7 | 51.9 ± 8.4 | 53.2 ± 8.9 | NA | 0.632 |

| FIGO stage III-IV | 33 (42.3) | 37 (56.9) | 27 (44.3) | 63 (76.8) | NA | < 0.001b |

| ECOG score 2 | 10 (12.8) | 12 (18.5) | 10 (13.5) | 22 (26.8) | NA | 0.021a |

| CA125 (U/mL, median) | 425.3 | 631.7 | 458.2 | 876.5 | NA | < 0.001b |

| Psychological status | ||||||

| SAS score | 48.5 ± 6.7 | 52.1 ± 6.9 | 46.9 ± 6.4 | 56.3 ± 7.2 | 25.64 | < 0.001b |

| Anxiety incidence | 28 (35.9) | 31 (47.7) | 18 (29.5) | 48 (58.5) | 14.87 | 0.002b |

| SDS score | 50.2 ± 6.5 | 53.6 ± 7.1 | 49.1 ± 6.6 | 58.4 ± 6.9 | 27.32 | < 0.001b |

| Depression incidence | 30 (38.5) | 32 (49.2) | 19 (31.1) | 51 (62.2) | 16.53 | 0.001b |

| Psychological adjustment (PACS scale) | ||||||

| Positive coping | 25.3 ± 3.2 | 24.1 ± 3.3 | 28.5 ± 3.6 | 22.8 ± 3.4 | 18.97 | < 0.001b |

| Negative avoidance | 22.7 ± 3.5 | 24.8 ± 3.6 | 20.5 ± 3.2 | 26.9 ± 3.8 | 19.85 | < 0.001b |

| Social support utilization | 25.2 ± 3.4 | 24.9 ± 3.5 | 22.7 ± 3.1 | 21.3 ± 3.0 | 17.26 | < 0.001b |

| Quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30) | ||||||

| Global quality of life | 67.3 ± 7.9 | 63.5 ± 8.1 | 72.6 ± 8.5 | 58.9 ± 8.3 | 26.38 | < 0.001b |

| Physical functioning | 70.2 ± 8.3 | 65.4 ± 8.0 | 74.8 ± 8.6 | 62.1 ± 8.2 | 22.76 | < 0.001b |

| Emotional functioning | 65.7 ± 7.6 | 61.3 ± 7.5 | 69.8 ± 8.0 | 56.2 ± 7.3 | 24.93 | < 0.001b |

| Symptom severity (EORTC QLQ-C30) | ||||||

| Fatigue | 36.5 ± 6.2 | 48.9 ± 7.1 | 32.4 ± 5.9 | 45.2 ± 7.0 | 30.68 | < 0.001b |

| Nausea and vomiting | 28.7 ± 5.6 | 42.3 ± 6.7 | 25.1 ± 5.3 | 36.8 ± 6.3 | 31.25 | < 0.001b |

| Pain | 32.6 ± 5.8 | 30.7 ± 5.7 | 27.3 ± 5.5 | 38.5 ± 6.5 | 24.69 | < 0.001b |

| Insomnia | 37.8 ± 6.3 | 40.2 ± 6.6 | 33.1 ± 6.0 | 45.6 ± 7.2 | 25.82 | < 0.001b |

| Treatment outcomes | ||||||

| Complete adherence | 62 (79.5) | 46 (70.8) | 52 (85.2) | 53 (64.6) | 16.94 | 0.010a |

| Partial adherence | 12 (15.4) | 14 (21.5) | 7 (11.5) | 19 (23.2) | NA | NA |

| Non-adherence | 4 (5.1) | 5 (7.7) | 2 (3.3) | 10 (12.2) | NA | NA |

| Two-year survival rate | 62 (79.5) | 49 (75.4) | 51 (83.6) | 57 (69.5) | 4.83 | 0.185 |

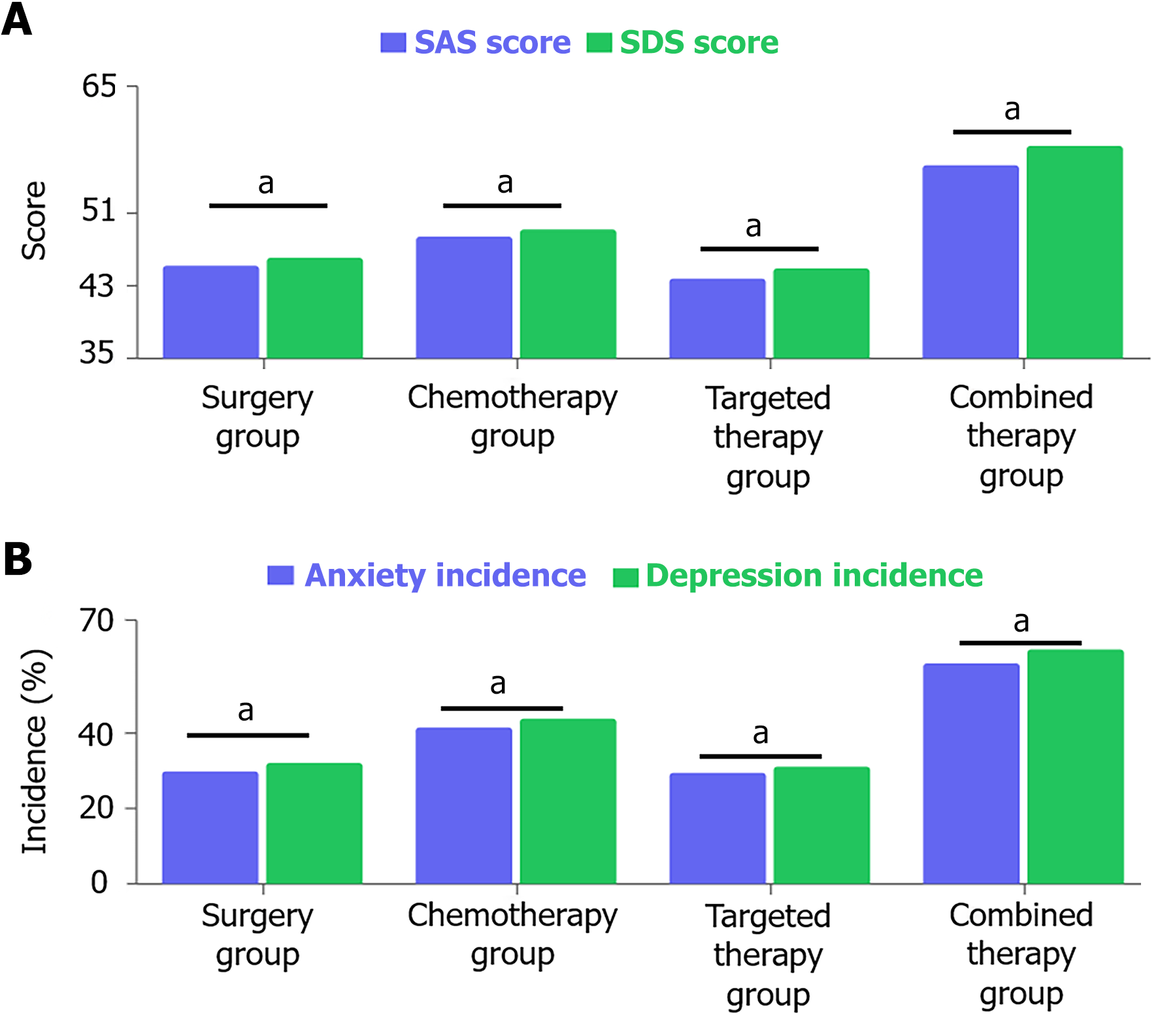

Patients in the combined therapy group had significantly higher SAS scores (56.3 ± 7.2) and SDS scores (58.4 ± 6.9) than the surgery group (SAS: 48.5 ± 6.7; SDS: 50.2 ± 6.5), chemotherapy group (SAS: 52.1 ± 6.9; SDS: 53.6 ± 7.1), and targeted therapy group (SAS: 46.9 ± 6.4; SDS: 49.1 ± 6.6; P < 0.05). The incidence of anxiety in the four groups was 35.9% (28/78) in the surgery group, 47.7% (31/65) in the chemotherapy group, 29.5% (18/61) in the targeted therapy group, and 58.5% (48/82) in the combined therapy group; the incidence of depression was 38.5% (30/78) in the surgery group, 49.2% (32/65) in the chemotherapy group, 31.1% (19/61) in the targeted therapy group, and 62.2% (51/82) in the combined therapy group (Figure 1).

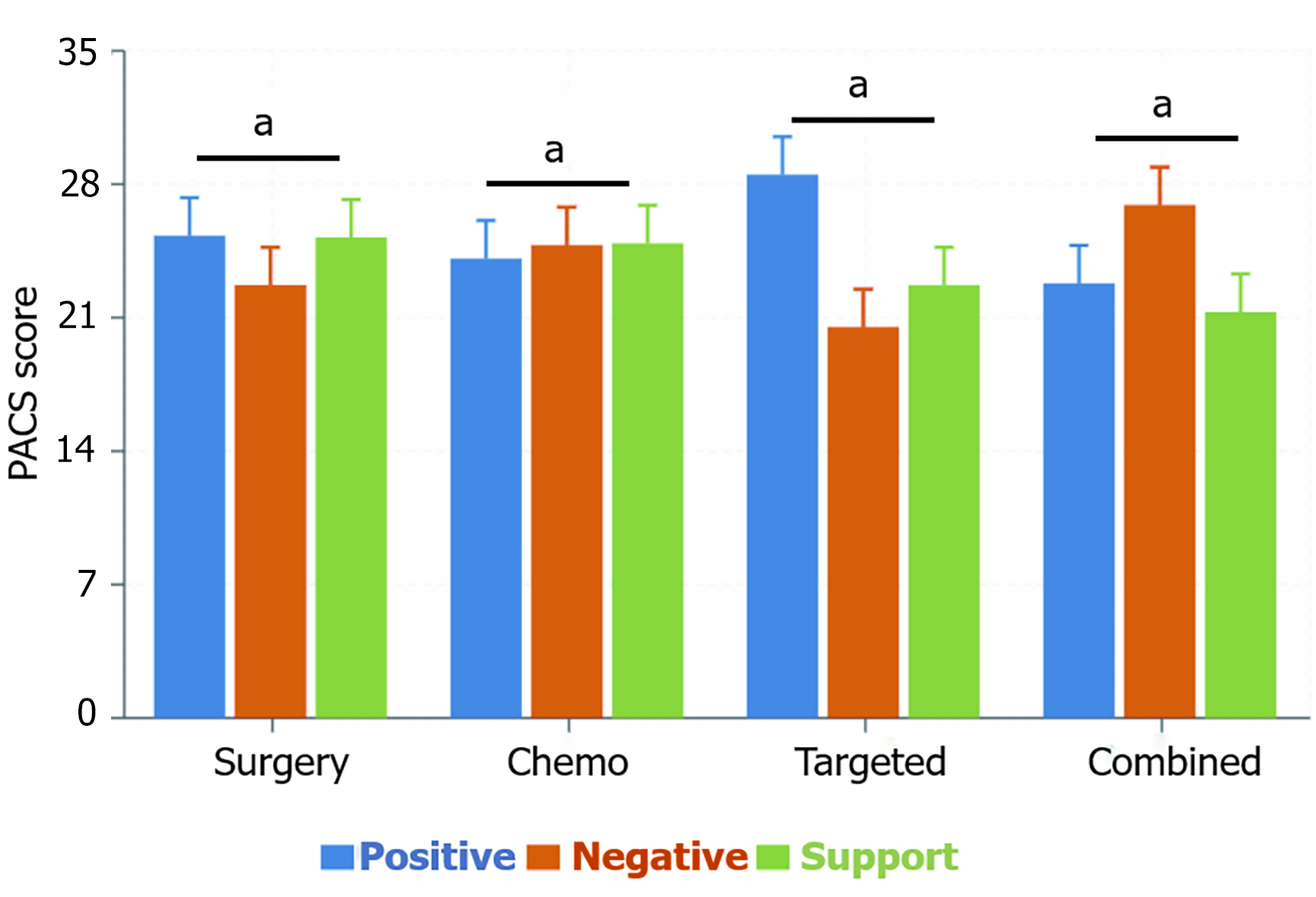

PACS scale assessment showed significant differences in psychological adjustment among the groups. The targeted therapy group scored highest in the positive coping dimension (28.5 ± 3.6), significantly higher than the surgery group (25.3 ± 3.2), chemotherapy group (24.1 ± 3.3), and combined therapy group (22.8 ± 3.4), F = 18.97, P < 0.05; while the combined therapy group scored highest in the negative avoidance dimension (26.9 ± 3.8), significantly higher than the chemotherapy group (24.8 ± 3.6), surgery group (22.7 ± 3.5), and targeted therapy group (20.5 ± 3.2), F = 19.85, P < 0.01. In the social support utilization dimension, the surgery group (25.2 ± 3.4) and chemotherapy group (24.9 ± 3.5) had similar scores and were significantly higher than the targeted therapy group (22.7 ± 3.1) and combined therapy group (21.3 ± 3.0), F = 17.26; P < 0.05. These results indicate that ovarian cancer patients receiving different treatment modalities show significant differences in coping strategy selection and social support utilization ability, with the targeted therapy group exhibiting a more positive and healthy psychological adjustment pattern (Figure 2).

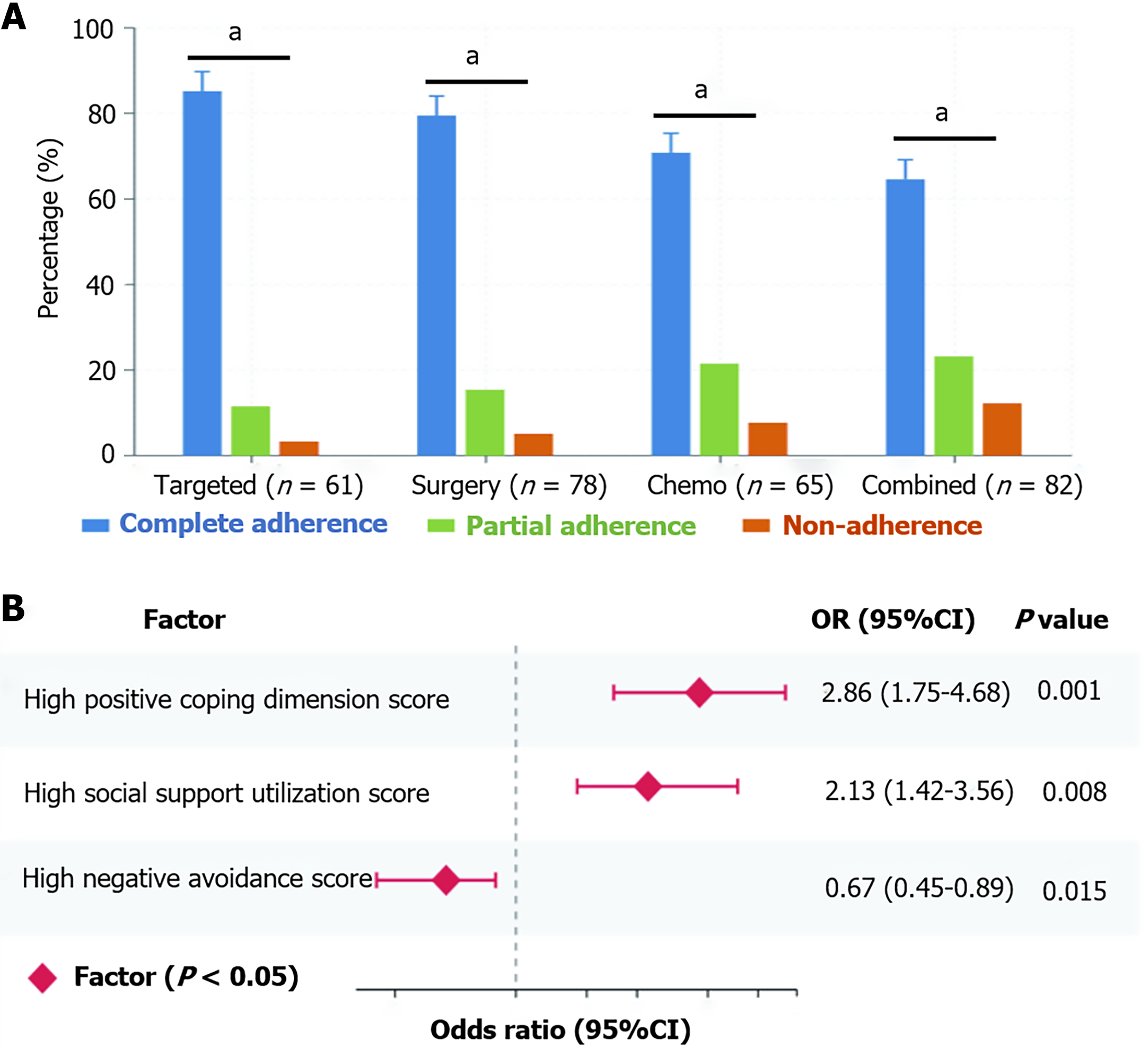

The study found significant differences in treatment adherence among different treatment groups, with the targeted therapy group having the highest complete adherence rate at 85.2% (52/61), significantly higher than the surgery group’s 79.5% (62/78), chemotherapy group’s 70.8% (46/65), and combined therapy group’s 64.6% (53/82), χ2 = 16.94, P < 0.05. Further analysis of partial adherence rates showed that the targeted therapy group had only 11.5% (7/61), lower than the surgery group’s 15.4% (12/78), chemotherapy group’s 21.5% (14/65), and combined therapy group’s 23.2% (19/82). In terms of non-adherence rates, the combined therapy group had the highest at 12.2% (10/82), far higher than the targeted therapy group’s 3.3% (2/61), surgery group’s 5.1% (4/78), and chemotherapy group’s 7.7% (5/65). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that, after controlling for confounding factors such as age, education level, and FIGO stage, high scores in the positive coping dimension of the PACS scale [odds ratio (OR) = 2.86, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.75-4.68, P < 0.001] and high scores in the social support utilization dimension (OR = 2.13, 95%CI: 1.42-3.56, P = 0.008) were independent protective factors for good treatment adherence, while high scores in the negative avoidance dimension (OR = 0.67, 95%CI: 0.45-0.89, P = 0.015) were a risk factor for poor treatment adherence (Figure 3).

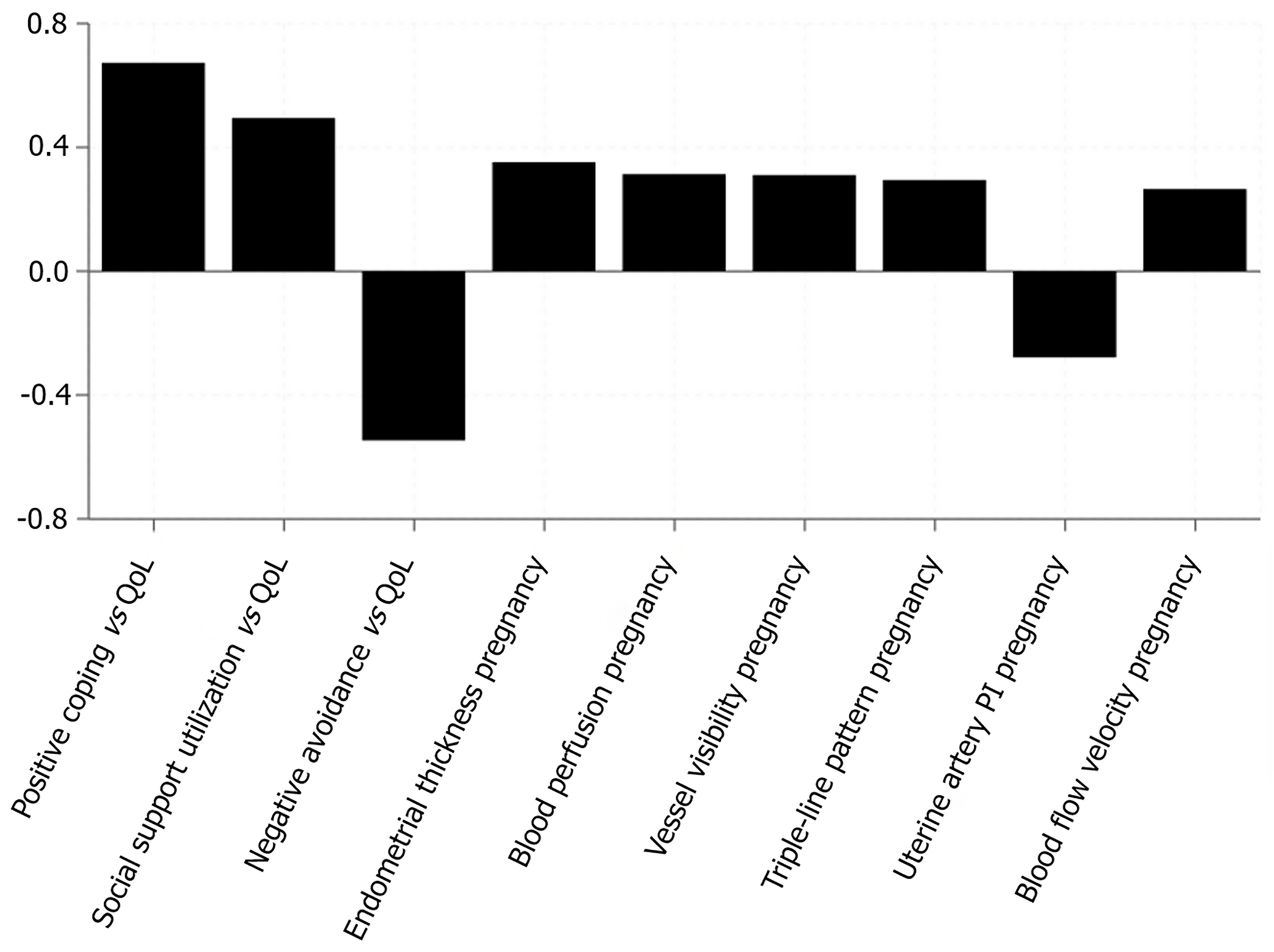

Pearson correlation analysis showed that PACS positive coping dimension scores were strongly positively correlated with EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 total scores (r = 0.673, P < 0.001), negative avoidance dimension scores were moderately negatively correlated with quality of life (r = -0.547, P < 0.001), and social support utilization dimension scores were moderately positively correlated with quality of life (r = 0.495, P < 0.001). These significant correlations between psychological adjustment factors and quality of life are similar to other clinical research findings, such as the positive correlation between endometrial thickness and clinical pregnancy rate (r = 0.352, P < 0.001), blood perfusion and pregnancy outcome (r = 0.314, P < 0.001), vessel visibility and pregnancy rate (r = 0.311, P < 0.001), and triple-line pattern and pregnancy success (r = 0.295, P < 0.001). This suggests that psychological adjustment ability may significantly impact clinical outcomes by influencing patients’ physiological functions and treatment processes, similar to the influence pattern of physiological factors reflected in the negative correlation between uterine artery pulsatility index value and pregnancy rate (r = -0.278, P < 0.001) and the positive correlation between subendometrial blood flow velocity and pregnancy rate (r = 0.265, P < 0.001; Figure 4).

The study conducted longitudinal follow-up assessments of patients, monitoring changes in psychological status at different treatment time points. At baseline measurement, the four groups’ SAS scores were 46.3 ± 6.2 points for the surgery group, 45.8 ± 6.5 points for the chemotherapy group, 45.5 ± 6.1 points for the targeted therapy group, and 47.2 ± 6.6 points for the combined therapy group, with no statistically significant differences between groups (F = 0.86, P = 0.463); SDS scores at baseline were similar, at 47.6 ± 6.3, 46.9 ± 6.1, 47.2 ± 6.2, and 48.4 ± 6.7 points, respectively (F = 0.92, P = 0.432). By the 3rd month of treatment, SAS scores in all four groups had significantly increased from baseline, with the surgery group increasing to 52.1 ± 7.0 points (t = 5.24, P < 0.01), chemotherapy group to 55.7 ± 7.3 points (t = 8.52, P < 0.001), targeted therapy group to 49.8 ± 6.8 points (t = 4.16, P < 0.01), and combined therapy group to 58.9 ± 7.5 points (t = 9.35, P < 0.001); SDS scores showed a similar trend, with the four groups increasing to 53.4 ± 6.8, 56.9 ± 7.4, 51.2 ± 6.5, and 60.5 ± 7.6 points, respectively, with the most significant increases in the chemotherapy and combined therapy groups (P < 0.001). At the 6th month follow-up, the targeted therapy group and surgery group showed a significant downward trend in anxiety and depression scores, with the targeted therapy group’s SAS decreasing to 45.7 ± 6.3 points (vs 3rd month, t = 3.68, P < 0.05) and the surgery group to 47.9 ± 6.5 points (t = 3.42, P < 0.05); while the combined therapy group mai

| Treatment group | Assessment scale | Baseline | Month 3 | t value (vs baseline) | P value (vs baseline) | Month 6 | t value (vs month 3) | P value (vs month 3) |

| Surgery group (n = 78) | SAS score | 46.3 ± 6.2 | 52.1 ± 7.0b | t = 5.24 | < 0.01 | 47.9 ± 6.5a | t = 3.42 | 0.02 |

| SDS score | 47.6 ± 6.3 | 53.4 ± 6.8b | t = 5.36 | < 0.01 | 48.8 ± 6.6a | t = 3.81 | 0.03 | |

| Chemotherapy group (n = 65) | SAS score | 45.8 ± 6.5 | 55.7 ± 7.3c | t = 8.52 | < 0.001 | 53.4 ± 7.1 | t = 1.86 | 0.07 |

| SDS score | 46.9 ± 6.1 | 56.9 ± 7.4c | t = 8.94 | < 0.001 | 55.2 ± 7.3 | t = 1.43 | 0.16 | |

| Targeted therapy group (n = 61) | SAS score | 45.5 ± 6.1 | 49.8 ± 6.8b | t = 4.16 | < 0.01 | 45.7 ± 6.3a | t = 3.68 | 0.02 |

| SDS score | 47.2 ± 6.2 | 51.2 ± 6.5b | t = 3.85 | < 0.01 | 46.9 ± 6.4a | t = 3.96 | 0.01 | |

| Combined therapy group (n = 82) | SAS score | 47.2 ± 6.6 | 58.9 ± 7.5c | t = 9.35 | < 0.001 | 56.8 ± 7.4 | t = 1.56 | 0.12 |

| SDS score | 48.4 ± 6.7 | 60.5 ± 7.6c | t = 9.86 | < 0.001 | 59.3 ± 7.5 | t = 0.87 | 0.39 | |

| Between-group comparison | SAS score | F = 0.86; P = 0.463 | F = 18.43; P < 0.001 | F = 24.67; P < 0.001 | ||||

| SDS score | F = 0.92; P = 0.432 | F = 20.35; P < 0.001 | F = 25.82; P < 0.001 |

This study implemented systematic psychological interventions for 76 patients, including CBT (n = 31), MBSR (n = 25), and SPT (n = 20), with an intervention cycle of 8 weeks (60-90 minutes per week). Before-and-after comparison showed that patients’ treatment adherence significantly improved, with the complete adherence rate increasing from 67.1% (51/76) before intervention to 89.8% (68/76) after intervention, an increase of 22.7% (χ2 = 11.37, P < 0.01); overall quality of life score increased from 60.3 ± 7.8 before intervention to 75.9 ± 8.4 after intervention, an increase of 15.6 points (t = 11.86, P < 0.01), with functional dimension improvement particularly notable (increased by 18.9 points, P < 0.001). Psychological status assessment showed that after intervention, the average SAS score decreased by 9.7 points (from 53.8 ± 7.2 to 44.1 ± 6.8, t = 8.36, P < 0.001), and the SDS score decreased by 10.4 points (from 55.6 ± 7.4 to 45.2 ± 6.9, t = 9.24, P < 0.001). Group analysis indicated that the intervention effects varied among different treatment groups, with the combined therapy group showing the most significant improvement, with anxiety incidence decreasing from 58.5% (17/29) to 28.0% (8/29) after intervention, a decrease of 30.5 percentage points (χ² = 16.32, P < 0.001); depression incidence decreased from 62.2% (18/29) to 36.4% (10/29), a decrease of 25.8 percentage points (χ² = 14.76, P < 0.001). While the targeted therapy group showed statistically significant improvement but of smaller magnitude, with anxiety incidence decreasing by 13.2 percentage points (χ² = 4.83, P = 0.034) and depression incidence decreasing by 11.7 percentage points (χ² = 4.55, P = 0.042; Table 3).

| Assessment category | Indicator | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Change | Statistics | P value |

| Overall effects (n = 76) | Complete adherence | 51 (67.1) | 68 (89.8) | +22.7% | χ2 = 11.37 | < 0.01 |

| QoL global score | 60.3 ± 7.8 | 75.9 ± 8.4 | +15.6 | t = 11.86 | < 0.01 | |

| Functional domain | 58.7 ± 7.5 | 77.6 ± 8.3 | +18.9 | t = 15.27 | < 0.001 | |

| SAS score | 53.8 ± 7.2 | 44.1 ± 6.8 | -9.7 | t = 8.36 | < 0.001 | |

| SDS score | 55.6 ± 7.4 | 45.2 ± 6.9 | -10.4 | t = 9.24 | < 0.001 | |

| Treatment group effects | ||||||

| Combined therapy group (n = 29) | Anxiety incidence | 17 (58.5) | 8 (28.0) | -30.5% | χ2 = 16.32 | < 0.001 |

| Depression incidence | 18 (62.2) | 10 (36.4) | -25.8% | χ2 = 14.76 | < 0.001 | |

| SAS score | 56.8 ± 7.5 | 45.3 ± 6.9 | -11.5 | t = 10.52 | < 0.001 | |

| SDS score | 59.1 ± 7.8 | 47.4 ± 7.1 | -11.7 | t = 11.08 | < 0.001 | |

| QoL score | 58.3 ± 7.6 | 75.2 ± 8.3 | +16.9 | t = 12.34 | < 0.001 | |

| Chemotherapy group (n = 20) | Anxiety incidence | 10 (50.0) | 5 (25.0) | -25.0% | χ2 = 10.24 | < 0.01 |

| Depression incidence | 11 (55.0) | 7 (35.0) | -20.0% | χ2 = 8.75 | < 0.01 | |

| SAS score | 54.9 ± 7.3 | 44.8 ± 6.8 | -10.1 | t = 8.73 | < 0.001 | |

| SDS score | 56.3 ± 7.5 | 46.2 ± 7.0 | -10.1 | t = 8.92 | < 0.001 | |

| QoL score | 60.8 ± 7.7 | 75.6 ± 8.3 | +14.8 | t = 10.46 | < 0.001 | |

| Surgery group (n = 12) | Anxiety incidence | 4 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) | -16.6% | χ2 = 5.62 | 0.023 |

| Depression incidence | 5 (41.7) | 3 (25.0) | -16.7% | χ2 = 5.83 | 0.021 | |

| SAS score | 52.1 ± 7.0 | 43.6 ± 6.7 | -8.5 | t = 6.54 | < 0.01 | |

| SDS score | 53.4 ± 7.1 | 44.8 ± 6.8 | -8.6 | t = 6.82 | < 0.01 | |

| QoL score | 61.8 ± 7.9 | 75.7 ± 8.4 | +13.9 | t = 9.47 | < 0.001 | |

| Targeted therapy group (n = 15) | Anxiety incidence | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.5) | -13.2% | χ2 = 4.83 | 0.034 |

| Depression incidence | 5 (33.3) | 3 (21.6) | -11.7% | χ2 = 4.55 | 0.042 | |

| SAS score | 49.8 ± 6.8 | 42.3 ± 6.5 | -7.5 | t = 5.68 | < 0.01 | |

| SDS score | 51.3 ± 7.0 | 43.5 ± 6.6 | -7.8 | t = 5.93 | < 0.01 | |

| QoL score | 64.2 ± 8.1 | 77.5 ± 8.6 | +13.3 | t = 9.21 | < 0.001 | |

Ovarian cancer, as one of the most threatening malignant tumors of the female reproductive system, involves a complex treatment process with highly uncertain prognosis, which often poses serious psychological challenges to patients during the disease coping process. Existing research indicates that approximately 40%-70% of ovarian cancer patients experience varying degrees of anxiety and depression symptoms after diagnosis, which not only reduces patients’ quality of life but may also indirectly affect disease prognosis by influencing treatment adherence, immune function, and neuroendocrine regulation[18-22]. However, systematic research on the impact of different treatment modalities on the psychological adjustment of ovarian cancer patients has been relatively lacking, especially comparative studies between emerging targeted therapies and traditional treatment methods. Our study addresses this critical knowledge gap by demonstrating that treatment modality serves as a significant determinant of psychological adaptation patterns, with implications extending beyond ovarian cancer to other malignancies.

The complexity and evolution of ovarian cancer treatment models are key to understanding the psychological burden on patients. Traditional surgical treatment often involves extensive pelvic organ removal and tissue reconstruction, which has profound effects on patients’ body image, fertility, and sexual function[23]. Chemotherapy, as the main adjuvant treatment for ovarian cancer, is usually accompanied by severe adverse reactions such as nausea, vomiting, hair loss, and bone marrow suppression[24]. These symptoms not only affect patients’ daily functioning but may also reinforce their fear of disease progression and death[25]. In contrast, targeted therapy represents a new direction in the era of precision medicine, with new drugs such as PARP inhibitors showing good efficacy and relatively low toxicity in ovarian cancer patients with specific gene mutations, potentially providing patients with different cognitive frameworks and treatment expectations for their disease. Our findings support this hypothesis, with targeted therapy patients demonstrating the most adaptive psychological profiles (highest positive coping scores 28.5 ± 3.6, lowest anxiety/depression incidence 29.5%/31.1%).

The psychological impact of different treatment modalities appears consistent across multiple cancer types, suggesting generalizable mechanisms underlying treatment-specific psychological responses. In breast cancer, recent studies have shown similar patterns to our findings[26]. Gastrointestinal cancer patients receiving immunotherapy demonstrated better psychological adjustment (PACS positive coping 26.8 ± 3.4) compared to combination chemotherapy groups (22.1 ± 3.7). However, our ovarian cancer cohort showed higher overall distress levels than these other cancer types, possibly reflecting ovarian cancers particularly poor prognosis and limited treatment options. The median anxiety scores in our combined therapy group (SAS 56.3 ± 7.2) were notably higher than comparable treatment groups in breast (51.8 ± 6.9) or colorectal cancer (49.2 ± 7.1), highlighting the unique psychological burden of ovarian cancer and supporting the need for cancer-specific psychological support protocols. Our stratified analyses reveal that the psychological benefits of targeted therapy persist even after controlling for disease severity markers. Among patients with advanced disease (International FIGO stage III-IV), the targeted therapy group (n = 27) maintained significantly lower psychological distress compared to other advanced-stage groups: SAS scores were 49.2 ± 6.8 (targeted therapy) vs 58.9 ± 7.4 (combined therapy), 54.3 ± 7.1 (chemotherapy), and 51.6 ± 6.9 (surgery) groups (P < 0.01). Similarly, among patients with ECOG performance status ≥ 2, the targeted therapy group demonstrated better psychological outcomes, though the effect size was somewhat attenuated (SAS 52.3 ± 7.0 vs 60.1 ± 7.8 in combined therapy, P < 0.05). These findings suggest that treatment modality effects on psychological adjustment are independent of disease burden, supporting the hypothesis that treatment characteristics themselves rather than merely reflecting disease severity directly influence psychological adaptation.

Psychological adjustment, as a core mechanism for cancer patients to cope with their disease, has evolved conceptually from a single dimension to multiple dimensions. Early research mainly focused on emotional responses and coping strategies, while modern psycho-oncology emphasizes that psychological adjustment is a complex dynamic process involving cognitive assessment, emotional regulation, behavioral coping, and social interaction[27-29]. In particular, the three dimensions assessed by the PACS positive coping, negative avoidance, and utilization of social support - provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding psychological adaptation in cancer patients. This multidimensional perspective helps explain why the same treatment method may trigger drastically different psychological responses in different patients, and why targeted therapy patients in our study demonstrated superior adaptation across multiple psychological domains simultaneously.

The influence of socio-cultural background on the psychological adjustment of ovarian cancer patients cannot be ignored and provides important context for our findings regarding social support utilization. Compared with Western societies, there are significant differences in disease attribution, family support patterns, and doctor-patient com

The results of this study indicate that ovarian cancer patients receiving different treatment modalities show significant differences in psychological adjustment patterns[35]. Patients in the combined therapy group exhibited the highest levels of anxiety and depression (SAS 56.3 ± 7.2; SDS 58.4 ± 6.9) and the strongest tendency toward negative avoidance (26.9 ± 3.8), possibly reflecting the cumulative psychological pressure brought by multi-modal treatment. In contrast, the targeted therapy group demonstrated a more positive psychological adjustment pattern, with significantly lower incidence of anxiety and depression (29.5%/31.1%) compared to other groups, and the highest score in positive coping ability (28.5 ± 3.6). This finding is consistent with the relatively lighter physical burden and higher targeting specificity of targeted therapy, supporting the hypothesis that precision treatment may bring dual benefits to both body and mind.

Notably, longitudinal assessment showed differences in psychological trajectories among different treatment groups: Although all patients experienced deterioration in psychological status at 3 months of treatment, the targeted therapy group and surgery group showed significant improvement at 6 months, while the combined therapy group maintained high levels of anxiety and depression. This suggests that treatment duration and complexity may be key factors affecting patients’ psychological recovery ability. More importantly, this study confirmed the significant effect of psychological intervention on improving patients’ treatment adherence (by 22.7%) and quality of life (by 15.6 points), especially for patients in the combined therapy group (anxiety incidence decreased by 30.5%), providing strong support for early psychological intervention targeting high-risk patients in clinical practice.

The psychological adjustment ability of ovarian cancer patients is significantly influenced by treatment modality, which affects psychological health and quality of life by changing patients’ disease cognition, symptom experience, and social functioning. The findings of this study not only enrich the theoretical framework of ovarian cancer psycho-oncology but also provide an empirical basis for individualized psychological intervention strategies in clinical practice.

| 1. | Arden-Close E, Mitchell F, Davies G, Bell L, Fogg C, Tarrant R, Gibbs R, Yeoh CC. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: A Mixed-Methods Feasibility Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420908341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cartmel B, Hughes M, Ercolano EA, Gottlieb L, Li F, Zhou Y, Harrigan M, Ligibel JA, von Gruenigen VE, Gogoi R, Schwartz PE, Risch HA, Lu L, Irwin ML. Randomized trial of exercise on depressive symptomatology and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in ovarian cancer survivors: The Women's Activity and Lifestyle Study in Connecticut (WALC). Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:587-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hill EM, Frost A. Loneliness and Psychological Distress in Women Diagnosed with Ovarian Cancer: Examining the Role of Self-Perceived Burden, Social Support Seeking, and Social Network Diversity. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2022;29:195-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Horesh D, Kohavi S, Shilony-Nalaboff L, Rudich N, Greenman D, Feuerstein JS, Abbasi MR. Virtual Reality Combined with Artificial Intelligence (VR-AI) Reduces Hot Flashes and Improves Psychological Well-Being in Women with Breast and Ovarian Cancer: A Pilot Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10:2261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu S, Baraghoshi D, Chang CP, Rowe K, Snyder J, Deshmukh V, Newman M, Fraser A, Smith K, Peoples AR, Gaffney D, Hashibe M. Mental health disorders among ovarian cancer survivors in a population-based cohort. Cancer Med. 2023;12:1801-1812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu L, Li X, Qian X, Wang S, Liu J, Yan J. Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Delivery Carrier-Assisted Targeted Controlled Release mRNA Vaccines in Tumor Immunity. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12:186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jin P, Sun LL, Li BX, Li M, Tian W. High-quality nursing care on psychological disorder in ovarian cancer during perioperative period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim SY, Lee Y, Koh SB. Factors Affecting the Occurrence of Mental Health Problems in Female Cancer Survivors: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:8615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li G, Zhang X. The effect of supportive and educational nursing care on quality of life and HE4 gene expression in patients with ovarian cancer. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2022;68:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Palagini L, Miniati M, Massa L, Folesani F, Marazziti D, Grassi L, Riemann D. Insomnia and circadian sleep disorders in ovarian cancer: Evaluation and management of underestimated modifiable factors potentially contributing to morbidity. J Sleep Res. 2022;31:e13510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pang X, Li F, Zhang Y. The Role of Mental Adjustment in Mediating Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Social Support in Chinese Ovarian Cancer Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:2183-2191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu L, Zhong Y, Wu D, Xu P, Ruan X, Yan J, Liu J, Li X. Immunomodulatory Factor TIM3 of Cytolytic Active Genes Affected the Survival and Prognosis of Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients by Multi-Omics Analysis. Biomedicines. 2022;10:2248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Petricone-Westwood D, Galica J, Hales S, Stragapede E, Lebel S. An Investigation of the Effect of Attachment on Distress among Partners of Patients with Ovarian Cancer and Their Relationship with the Cancer Care Providers. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:2950-2960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Petricone-Westwood D, Stragapede E, Galica J, Hales S, Lebel S. An investigation of fear of recurrence, attachment and caregiving experiences among ovarian cancer partner-caregivers. Psychooncology. 2022;31:1136-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Polen-De C, Langstraat C, Asiedu GB, Jatoi A, Kumar A. Advanced ovarian cancer patients identify opportunities for prehabilitation: A qualitative study. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2021;36:100731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schrier E, Xiong N, Thompson E, Poort H, Schumer S, Liu JF, Krasner C, Campos SM, Horowitz NS, Feltmate C, Konstantinopoulos PA, Dinardo MM, Tayob N, Matulonis UA, Patel M, Wright AA. Stepping into survivorship pilot study: Harnessing mobile health and principles of behavioral economics to increase physical activity in ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:581-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Su LJ, O'Connor SN, Chiang TC. Association Between Household Income and Self-Perceived Health Status and Poor Mental and Physical Health Among Cancer Survivors. Front Public Health. 2021;9:752868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tsai LY, Tsai JM, Tsay SL. Life experiences and disease trajectories in women coexisting with ovarian cancer. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59:115-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wall JA, Lipking K, Smith HJ, Huh WK, Salter T, Liang MI. Moderate to severe distress in half of ovarian cancer patients undergoing treatment highlights a need for more proactive symptom and psychosocial management. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;166:503-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yunokawa M, Onda T, Ishikawa M, Yaegashi N, Kanao H. Current treatment status of older patients with gynecological cancers. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2022;52:825-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Amiri S. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms/disorders in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1422540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Frost J, Newton C, Dumas L. Holistic Integrated Care in Ovarian Cancer (HICO)-reducing inequalities due to age, frailty, poor physical and mental health. BMJ Open Qual. 2025;14:e002714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ghamari D, Dehghanbanadaki H, Khateri S, Nouri E, Baiezeedi S, Azami M, Ezzati Amini E, Moradi Y. The Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Women with Ovarian Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2023;24:3315-3325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gorman M, Shih K. Updates in Hormone Replacement Therapy for Survivors of Gynecologic Cancers. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2025;26:179-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Han X, Lin X, Li G, Wang J, Meng X, Chen T, Zhang Y, Fu X. Association of cancer and schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorder: A Mendelian randomization study. J Psychosom Res. 2024;183:111806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wu L, Liu Q, Ruan X, Luan X, Zhong Y, Liu J, Yan J, Li X. Multiple Omics Analysis of the Role of RBM10 Gene Instability in Immune Regulation and Drug Sensitivity in Patients with Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD). Biomedicines. 2023;11:1861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Iavarone I, Padovano M, Pasanisi F, Della Corte L, La Mantia E, Ronsini C. Meigs Syndrome and Elevated CA-125: Case Report and Literature Review of an Unusual Presentation Mimicking Ovarian Cancer. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Johansen G, Lampic C, Flöter Rådestad A, Dahm-Kähler P, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA. Health-related quality of life, sexual function, psychological health, reproductive concerns and fertility outcome in young women treated with fertility-sparing surgery for ovarian tumors - A prospective longitudinal multicentre study. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;189:101-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Johnston EA, Veenhuizen SGA, Ibiebele TI, Webb PM, van der Pols JC; OPAL Study Group. Mental health and diet quality after primary treatment for ovarian cancer. Nutr Diet. 2024;81:215-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lakhiani A, Cummins C, Kumar S, Long J, Arora V, Balega J, Broadhead T, Duncan T, Edmondson R, Fotopoulou C, Glasspool R, Kolomainen D, Manchanda R, McNally O, Morrison J, Mukhopadhyay A, Naik R, Wood N, Sundar S. Analysis of Anxiety, Depression and Fear of Progression at 12 Months Post-Cytoreductive Surgery in the SOCQER-2 (Surgery in Ovarian Cancer-Quality of Life Evaluation Research) Prospective, International, Multicentre Study. Cancers (Basel). 2023;16:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Merritt MA, Abe SK, Islam MR, Rahman MS, Saito E, Katagiri R, Shin A, Choi JY, Le Marchand L, Killeen JL, Gao YT, Tamakoshi A, Koh WP, Sakata R, Sawada N, Tsuji I, Sugawara Y, Kim J, Park SK, Kweon SS, Shu XO, Kimura T, Yuan JM, Tsugane S, Kanemura S, Lu Y, Shin MH, Wen W, Ahsan H, Boffetta P, Chia KS, Matsuo K, Qiao YL, Rothman N, Zheng W, Inoue M, Kang D. Reproductive factors and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: results from the Asia Cohort Consortium. Br J Cancer. 2025;132:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pegreffi F, Di Fiore R, Suleiman S, Veronese N, Fiorenza G, Pecorino B, Scollo P, Calleja-Agius J. Exploring the impact of exercise on women with ovarian cancer: A call for more methodologically standardized RCTs to enable a realistic systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2025;51:109556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ren H, Meng S, Yin X, Li P, Xue Y, Xin W, Li H. Effects of expressive writing of positive emotions on mental health among patients with ovarian cancer undergoing postoperative chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2025;74:102756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Telles R, Zimmerman MB, Thaker PH, Slavich GM, Ramirez ES, Zia S, Goodheart MJ, Cole SW, Sood AK, Lutgendorf SK. Rural-urban disparities in psychosocial functioning in epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;184:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tookman L, Green C, Leonard K, Clare V, Patel N, Dunlop F, McCormack S, Ellis H, de Courcy J, Bateman L, Borley J. Diagnosis, treatment and burden in advanced ovarian cancer: a UK real-world survey of healthcare professionals and patients. Future Oncol. 2024;20:1657-1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/