Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111580

Revised: August 26, 2025

Accepted: October 10, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 146 Days and 7.2 Hours

Adolescent depression manifests through diverse, interconnected symptoms, yet the clinical profile in patients treated with repetitive transcranial magnetic sti

To identify adolescent depression symptom clusters and assess their differential responses to rTMS treatment.

One hundred adolescent patients with first-episode major depressive disorder were randomized into control and study groups. Both groups received sertraline treatment, while the study group additionally underwent 10 sessions of adjunc

Hierarchical clustering revealed four distinct symptom clusters: Subjective mood, impaired activity, somatic concerns, and anxiety/insomnia. The main effect of treatment visit showed significant decreases in symptom severity across all clusters. In the study group, the effect size between baseline and week 4 was largest for the subjective mood cluster (Cohen’s d = 2.41) and smallest for somatic concerns (Cohen’s d = 0.59). In the control group, the largest effect size was observed in the anxiety/in

This study identified four distinct symptom clusters with differential responses to rTMS treatment. The findings demonstrate that rTMS shows greatest efficacy for improving subjective mood symptoms, guiding targeted the

Core Tip: This study reveals that adolescent depression consists of four distinct symptom clusters (subjective mood, impaired activity, somatic concerns, and anxiety/insomnia) which respond differentially to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). The most significant improvement was observed in the subjective mood cluster, suggesting that rTMS may be most effective for core emotional symptoms. These findings are critical for moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and opti

- Citation: Liu WJ, Chen WL, Chen HS. Exploratory analysis of symptom-specific efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation in adolescent depression. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 111580

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/111580.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111580

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by persistent low mood, diminished interest, and reduced energy, with associated high rates of recurrence and suicide. Epidemiological research indicates that 13.3% of adolescents in the United States have experienced at least one major depressive episode[1]. In China, depression detection rates among high school students range from 10.9% to 12.6%[2], with lifetime prevalence of severe depressive disorders reaching 20%. These conditions lead to significant impairments in social and occupational functioning, elevated suicide risks, and poor response and remission rates to antidepressant treatment.

The treatment of adolescent depression presents unique challenges because symptom presentation differs substantially from that in adults. Research has demonstrated that vegetative symptoms (e.g., appetite/weight changes, fatigue, insomnia) occur more frequently in adolescent MDD, whereas anhedonia and concentration difficulties predominate in adult MDD[3]. Moreover, therapeutic efficacy is generally lower in adolescents compared to adults. Currently, the Food and Drug Administration has approved only two selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors - fluoxetine and escitalopram - for adolescent depression.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) offers a promising alternative intervention. By targeting dysfunctional neural circuits, rTMS has demonstrated efficacy in achieving symptom remission in adolescent depression[4-6]. This highlights the critical need to investigate how specific symptom clusters evolve during treatment, particularly in response to novel neuromodulatory approaches like rTMS.

Traditional assessment methods often rely on sum scores from psychometric scales or factor analyses that fail to fully capture the complexity of depressive symptoms. These approaches often overlook the interplay between symptoms and the unique presentation of depression in adolescents[7]. Limitations include insufficient sensitivity to diverse manifestations of depression and inability to account for the dynamic nature of symptom clusters. Consequently, more nuanced assessment tools are needed to better reflect the complexities of adolescent depression and inform more effective, tailored treatment strategies.

Symptom clusters - groups of two or more simultaneously occurring, interrelated symptoms - have become an im

Previous factor analysis studies using standard depression assessment tools have identified four symptom dimensions[9]: (1) Somatic anxiety/somatization; (2) Psychic anxiety; (3) Pure depression; and (4) Anorexia. Similarly, research employing Exploratory Graph Analysis has identified four distinct symptom clusters in adolescent depression: Impaired activity, somatic concerns, subjective mood, and observed affect[10].

To our knowledge, only two studies have examined differential symptom response to rTMS[11,12]. One study investigated magnetic resonance imaging voxel-based connectivity clustering in individuals with varying depression levels who underwent rTMS[11]. The researchers identified two distinct neural circuit targets corresponding to two symptom clusters: One for dysphoric symptoms and another for anxiosomatic symptoms. Notably, treatment directed at the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) proved more effective in alleviating dysphoric symptoms than anxiosomatic symptoms. Another study[12] discovered four symptom clusters - mood, anxiety, insomnia, and somatic factors - in 596 participants with treatment-resistant depression via confirmatory factor analysis. Consistent with earlier findings, various symptom clusters responded differently to rTMS therapy, with anxiety-related symptoms showing markedly lower treatment response compared to other clusters. This suggests that rTMS may be more effective for certain depressive symptoms while less effective for anxiety-related symptoms, underscoring the importance of tailoring treatment approaches to specific symptom profiles.

While these findings have important implications, they are specific to the protocols used in these trials, with treatment delivery based on structural imaging localization. Furthermore, the study using two different forms of rTMS, which demonstrated non-inferiority, could potentially impact symptom clusters differentially. Although depression’s multidimensionality has been assessed in various clinical samples[9,11,12], to our knowledge, it has not been evaluated specifically in adolescents with depression referred for rTMS. Moreover, the limitations of traditional factor-based assessments highlight the need for more sophisticated diagnostic tools that can capture the complexity of depressive symptoms in adolescents.

The primary aim of our original work was to explore the early effects of rTMS combined with sertraline in adolescents with first-episode MDD[13]. That study supported that adjunctive rTMS accelerates antidepressant efficacy, improving depressive symptoms and cognitive function in first-episode adolescent depression. Building upon these findings, we sought to determine whether rTMS treatment would differentially impact identified symptom clusters in adolescent depression. Based on prior research[11,12], we hypothesized that targeting the left DLPFC would result in significantly greater improvement in mood symptom clusters compared to other symptom clusters. Confirmation of these hypotheses would represent an important advance in rTMS delivery and a significant step toward personalized treatment of adolescent depression.

This work constitutes a secondary analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial examining the effects of rTMS delivered to the left DLPFC in adolescents with depression in China[13]. The study included 100 adolescents (aged 12-18 years) with first-episode, medication-naive MDD. All participants met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and had a baseline 7-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) total score ≥ 17.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Severe or unstable physical illness; (2) History of head injury or seizure disorder; (3) Diagnosis of mental retardation, substance dependence or abuse (except nicotine and caffeine), bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or eating disorder as defined by DSM-IV; (4) Presence of metal implants; (5) Benzodiazepine use within 12 hours of cognitive assessments; and (6) Alcohol consumption within 8 hours of cognitive assessments.

Participants were recruited from inpatient and outpatient services at Hangzhou Seventh People’s Hospital from March to September 2021 and followed for one month. Sample size was determined a priori using GPower. Based on an effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.5) derived from the study by Kim et al[10], with α = 0.05 and power (1-β) = 0.95, analysis indicated a minimum required sample size of 38. The final sample size of n = 77 exceeded this requirement, confirming adequate power to detect the target effect.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the control group or the study group. The control group received sertraline for the first 2 weeks, while the study group received both sertraline and rTMS treatment on 10 consecutive workdays (Monday to Friday, for 2 weeks). Both groups were administered 50 mg sertraline daily for the first 2 weeks. During the subsequent 2 weeks, both groups continued sertraline treatment without stimulation. The sertraline dosage was increased to 100 mg daily if patients showed less than 50% reduction in HAMD-17 scores within the first 2 weeks of treatment. HAMD-17 scores, the primary outcome measure, were assessed at baseline, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks by blinded evaluators. Additional details about the trial and its results have been described elsewhere[13].

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou Seventh People’s Hospital, approval No. 2025-005 and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association, approval No. ChiCTR2500103629. All patients provided written informed consent, and for participants under 18 years old, written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian. No additional ethics approval or informed consent was required for this secondary analysis.

The primary outcome measure was the HAMD-17, a widely used clinician-rated psychometric measure of depression severity. Of the 17 items, nine are scored between 0 (not present) and 4 points (severe), while the remaining eight are scored between 0 (not present) and 2 points (severe), yielding a total score range from 0 to 52. Outcome assessments were conducted by trained research assistants blinded to treatment allocation. HAMD-17 scores were collected at baseline, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks by blinded evaluators. Further details regarding study procedures are available in the original publication[13].

Magstim rapid stimulators with a figure-8 coil (Magstim, Sheffield, United Kingdom) were operated by professional clinicians. For each participant, the resting motor threshold (RMT) was determined before the initial rTMS session. RMT was defined as the lowest intensity capable of eliciting a visible muscle contraction of the right abductor pollicus brevis in five of 10 trials, with amplitude of at least 50 μV. The study group received stimulation with a frequency of 10 Hz, at 90% RMT intensity for safety, comprising 60 trains with 4 seconds on and 15 seconds off, delivering 2400 pulses per session, five sessions per week. During each treatment session, stimulation was delivered to the left DLPFC, identified using the 5-cm rule. The TMS treatments were assigned according to a random number list. All patients were naïve to rTMS prior to study participation[13].

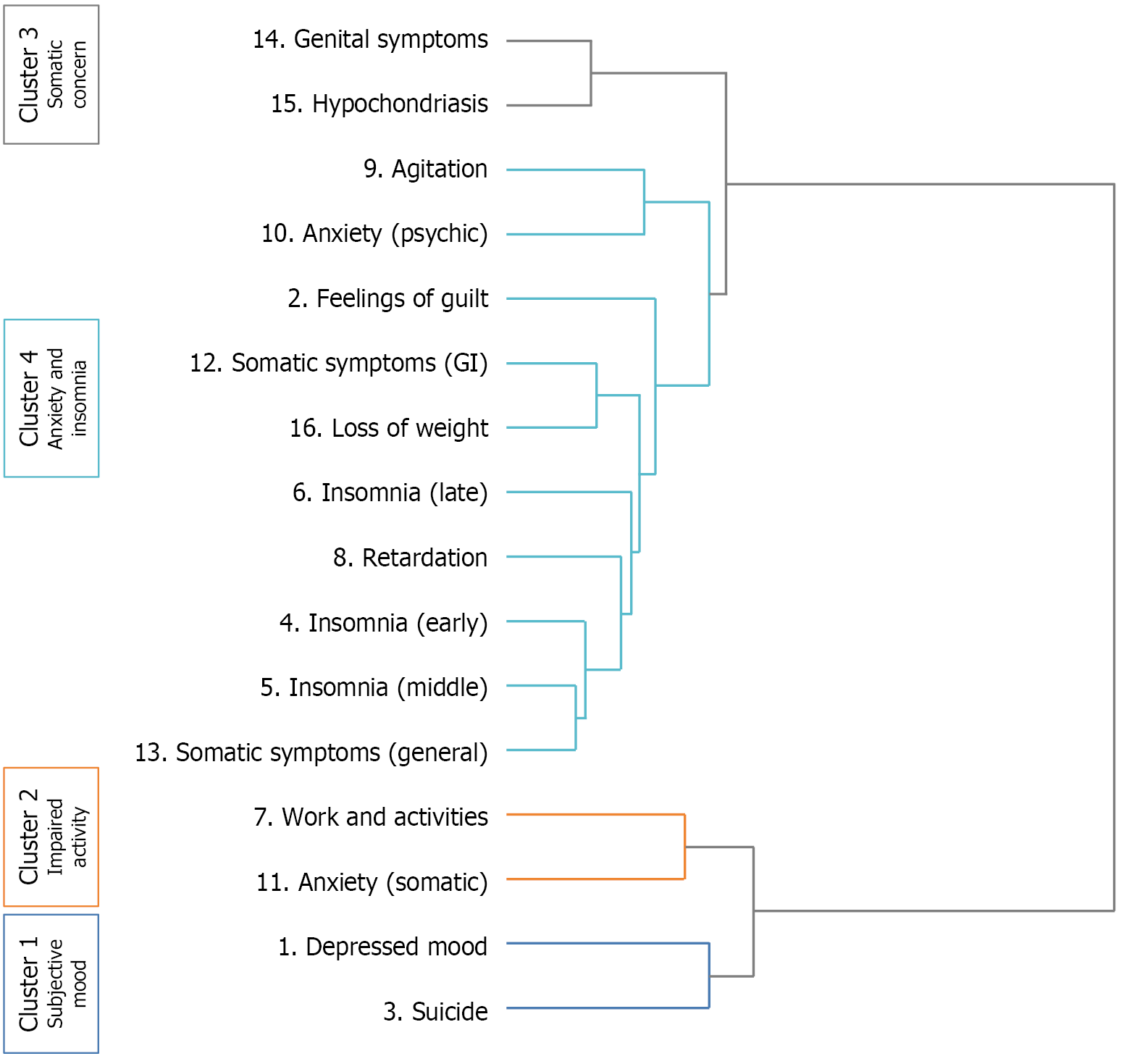

Rating scales in depression include a diverse range of symptoms. We applied a data-driven approach to identify groups of symptoms within HAMD-17. Hierarchical clustering shows structure in data without making assumptions about the number of clusters that are present in the data and gives a deterministic solution. We modified the model a priori by excluding the insight item because of: (1) Weak correlations with the HAMD-17 total score; (2) Low discriminative abilities; and (3) Poor item reliability[9,14]. Groups of co-occurring symptoms were established by clustering scores for each HAMD-17 item at baseline - symptoms were classified into clusters according to similarity in baseline score across the entire sample. We used Ward’s method with Euclidean distances for hierarchical agglomerative clustering[15]. Unlike some other clustering methods, hierarchical agglomerative clustering does not require a prespecified number of clusters. Rather, symptoms are progressively aggregated according to the distance metric and linkage criterion selected, until a cluster is formed. Investigators then define the number of clusters by identifying the moment when cluster formation produces groups that are either particularly dissimilar or useless for the research question[16]. The missingness mechanism was assessed by comparing baseline characteristics (age, gender, episode duration, education) between complete-case (n = 77) and missing-data (n = 20) groups via t-tests and χ2 tests. The absence of significant differences (all P > 0.05) supported the missing completely at random assumption, justifying the use of complete-case analysis for the secondary analysis (final n = 77).

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to examine the differences in symptom clusters at different time points within each group; the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized to examine the differences in symptom clusters between the study group and control groups at the same time point (0 week, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to quantify the magnitude of HAMD-17 score reductions at 2 weeks and trial endpoint (4 weeks), with thresholds interpreted as follows: D = 0.2 (small), 0.5 (medium), and 0.8 (large)[17].

The study initially enrolled 100 patients, yet 97 subjects completed all treatments. During the treatment phase, three patients were lost to follow-up. Specifically, two in the study group withdrew due to pain at the stimulation site, and one in the control group switched from sertraline to fluoxetine because of loss of appetite. Additionally, for the secondary analysis, a further reduction of 20 cases occurred - primarily due to data loss caused by equipment failure and improper storage during data collection - resulting in a final sample size of 77 subjects.

There were no differences in age, gender, education, the duration of the current episode, age at onset in the two groups. Mean total corrected HAMD-17 scores which excluding insight symptom of the HAMD-17, were similar across treatment group at baseline: 32.69 (SD 2.70) in 39 patients in the control group, 32.79 (SD 2.76) in the 38 patients in the combined treatment group. Further demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups have been described in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Control group (n = 39) | Study group (n = 38) | P value |

| Gender (female/male) | 32/7 | 31/7 | 0.908 |

| Age (years) | 14.9 ± 1.7 | 14.5 ± 2.0 | 0.407 |

| Duration of current episode (months) | 15.8 ± 18.9 | 18.0 ± 14.3 | 0.562 |

| Education (years) | 7.9 ± 1.7 | 7.5 ± 2.0 | 0.407 |

The clustering procedure showed that the Euclidean distance at which symptoms were merged into clusters tend to be small. The analysis supported a four-cluster model as the optimal solution for categorizing HAMD-17 symptom profiles (Figure 1). Cluster 1, referred to as “Subjective Mood”, encompassed symptoms of depressed mood and suicide. Cluster 2, known as “Impaired Activity”, included the symptoms of work and Interests and somatic anxiety. Cluster 3, termed “Somatic Concern”, consisted of symptoms like Genital Symptoms and Hypochondriasis. Cluster 4, categorized as “Anxiety and Insomnia”, comprised symptoms of sleep disturbances, appetite and psychic anxiety.

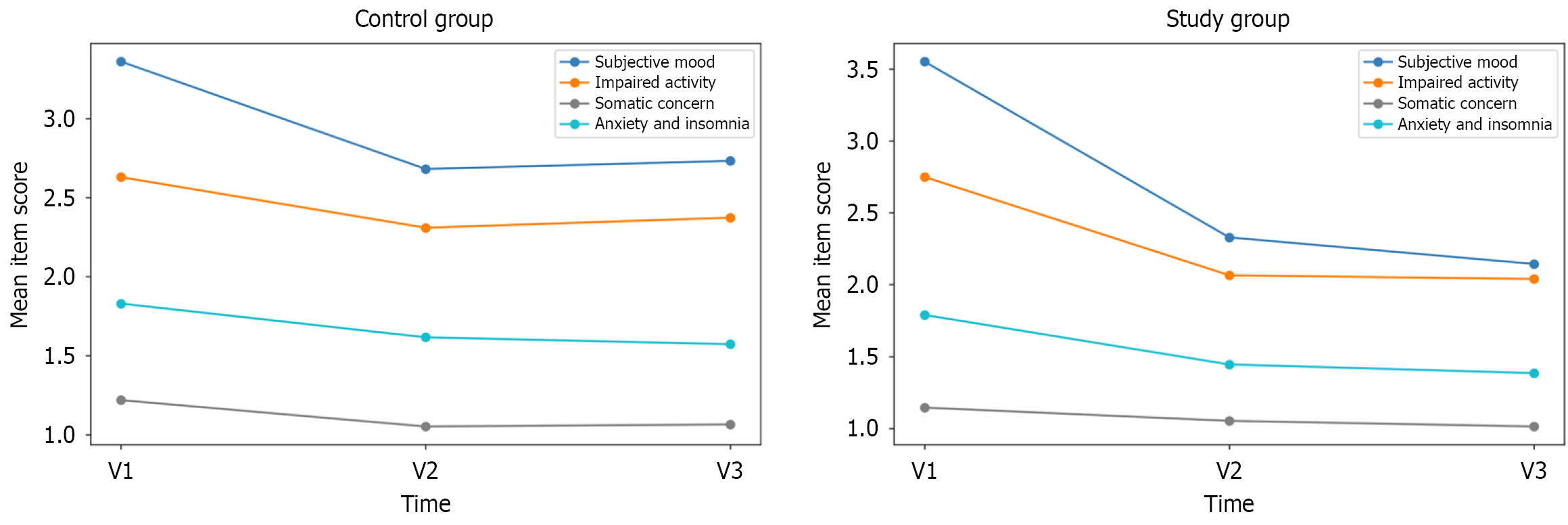

At the initial assessment (V1), no statistically significant differences were observed in the mean scores across the four symptom clusters between the two groups. Subsequent to the intervention period (V2), significant disparities became evident in the mean scores for clusters 2 and 4 between the two groups. Upon further evaluation at the subsequent assessment (V3), clusters 1, 2, and 4 all exhibited statistically significant differences in mean scores (Table 2).

| Participant | Statistical value | Subjective mood | Impaired activity | Somatic concern | Anxiety and insomnia |

| Control group (n = 39) | Score at V1 | 3.359 ± 0.537 | 2.628 ± 0.496 | 1.218 ± 0.276 | 1.828 ± 0.220 |

| Score at V2 | 2.679 ± 0.899b | 2.308 ± 0.481b | 1.051 ± 0.154b | 1.615 ± 0.233b | |

| Score at V3 | 2.731 ± 0.945b | 2.372 ± 0.593b | 1.064 ± 0.169b | 1.572 ± 0.206b | |

| Effect size (95%CI)1 | 0.82 (0.36-1.28) | 0.47 (0.02-0.92) | 0.67 (0.22, 1.13) | 1.20 (0.72-1.68) | |

| Study group (n = 38) | Score at V1 | 3.553 ± 0.530 | 2.750 ± 0.461 | 1.145 ± 0.305 | 1.789 ± 0.184 |

| Score at V2 | 2.329 ± 0.756b | 2.066 ± 0.606ab | 1.053 ± 0.156 | 1.445 ± 0.206ab | |

| Score at V3 | 2.145 ± 0.636ab | 2.039 ± 0.619ab | 1.013 ± 0.081b | 1.384 ± 0.222ab | |

| Effect size (95%CI)1 | 2.41 (1.82-3.00) | 1.30 (0.81-1.80) | 0.59 (0.13-1.05) | 1.98 (1.43-2.53) |

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the changes in mean scores in the four clusters during the study period. The main effect of a visit was significant with decreasing symptom severity alongside visits in all four clusters in both groups; however, the degree of symptom improvement differed among the four clusters. The effect size of score differences between V1 and V3 was the highest in the subjective mood cluster in the study group [Cohen’s d = 2.41, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.82-3.00], whereas it was the lowest in somatic concern in the study group (Cohen’s d = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.13-1.05). In the control group, the effect size of score differences between V1 and V3 was also the highest in the anxiety and insomnia cluster (Cohen’s d = 1.20, 95%CI: 0.72-1.68), with the lowest effect in impaired activity (Cohen’s d = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.02-0.92).

Our secondary analysis represents the first known investigation into symptom clusters associated with rTMS response in adolescent MDD. Using cluster analysis, we identified four distinct symptom domains within the HAMD-17: Subjective mood, impaired activity, somatic concerns, and anxiety/insomnia. Among these, subjective mood symptoms demon

Further subgroup analysis revealed that subjective mood exhibited the most substantial improvement among all clusters within the rTMS treatment group, while anxiety and insomnia symptoms showed greater improvement in the control group. These findings underscore the heterogeneity of treatment response and suggest specific clinical phe

Given the paucity of cluster-based analyses characterizing depressive symptoms in adolescents, we compared our findings with previous studies utilizing conventional factor analysis. Despite methodological differences, our symptom clusters demonstrated consistency with established factor structures of the HAMD-17[12,18]. Traditional categorization of HAMD-17 items into mood, anxiety, insomnia, and somatic factors derived from meta-analyses of exploratory factor analyses[18] - parallels our findings. While another data-driven approach identified three symptom clusters (sleep, core emotional, and atypical symptoms) in adult depression[19], few studies have specifically examined multidimensional symptom domains in adolescent depression or tracked symptom domain trajectories throughout rTMS treatment.

Our study demonstrates that symptom clusters in adolescent depression follow distinct trajectories in response to pharmacological and neuromodulatory interventions. This finding carries significant clinical implications, suggesting that comprehensive assessment of symptom clusters should inform treatment selection and outcome expectations in ado

Academic literature on depressive symptom clusters in adults describes a set that includes core emotional or general depression items (e.g., sad mood, anhedonia, low self-worth). This cluster had a better response to pharmacotherapy than other clusters in adults[19,20]. One study identified four symptom clusters including impaired activity, somatic concerns, subjective mood, and observed effect of Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised, which associated with adolescent depression and their differential changes related to antidepressant treatment. This finding suggests that escitalopram was the most effective at improving subjective mood including symptoms of irritability, guilty, and suicidal ideation among different clusters[10]. Our findings align with analyses conducted in pharmacotherapy trials, which consistently demonstrate that core “emotional” or “mood” symptoms exhibit greater responsiveness to pharmacotherapy compared to other individual items or symptom clusters[10,12,19,21-24]. However, discrepancies in analytical methodologies have led to the identification of symptom clusters that measure distinct constructs, such as “atypical” symptoms or cognitive symptoms[19,21]. These methodological variations complicate direct comparisons between our findings and previous research. Future comparative studies employing consistent analytical techniques across pharmacotherapy and rTMS interventions are necessary to determine whether our observations are specific to rTMS or represent patterns consistent across various depression treatment modalities.

The present findings align with previous neuroimaging studies that have demonstrated distinct responses of symptom clusters to rTMS[11,23]. In a prior investigation, it was hypothesized that rTMS administered to the DLPFC might exert a more pronounced effect on mood and dysphoric symptoms than on anxiety symptoms, a hypothesis that was corroborated in our study[11,12]. Additionally, another study has indicated that the number and timing of stimulation pulses do not significantly influence the differential response of symptom clusters in patients with treatment-resistant depression[12]. Furthermore, Zhao et al[25] has shown that daily intermittent theta burst stimulation, an innovative and promising variant of TMS, when applied to the left DLPFC over a two-week period, can effectively and safely reduce suicidal ideation and alleviate depressive mood in adolescent depression, particularly among individuals with more severe symptoms.

Although our study has several strengths, such as the development of a hypothesis evaluation framework and the exploration of hierarchical models to investigate the underlying factors contributing to the construct of depression, it is crucial to recognize the limitations. Firstly, the single-institution recruitment strategy may limit the generalizability of results and introduces the possibility of selection bias. Secondly, while the retrospective design introduces the possibility of unmeasured confounding, we emphasize that the original study was rigorously designed with strict, prospective patient selection criteria that served to create a homogeneous population and mitigate this concern. Additionally, the sample size for the secondary analysis decreased by 20 participants due to equipment failure and improper storage. Although formal testing indicated that these data were likely missing completely at random, and a complete-case analysis was therefore employed, this reduction may nonetheless diminish the statistical power of these analyses and potentially affect the precision of our estimates. Our study provides promising results on the preferential effect of adjunctive rTMS on the subjective mood cluster in adolescents with depression, future studies should incorporate a rigorous sham-controlled rTMS arm to unequivocally attribute the observed effects to the neurobiological action of rTMS. This would strengthen the causal inference and provide more definitive evidence for the clinical application of rTMS in this population.

In a nutshell this exploratory investigation represents an initial step toward understanding the evolution of symptom clusters during rTMS treatment for adolescent MDD. Future research will focus on validating these preliminary findings through the integration of behavioral assessments with neuroimaging data, including functional magnetic resonance imaging and functional near-infrared spectroscopy.

Our distinct symptom clusters characterize adolescent depression: Subjective mood, impaired activity, somatic concerns, and anxiety/insomnia. DLPFC-targeted rTMS produces differential effects across these symptom domains, with the subjective mood cluster - encompassing depressed mood and suicidal ideation - showing significantly greater imp

| 1. | Mullins N, Bigdeli TB, Børglum AD, Coleman JRI, Demontis D, Mehta D, Power RA, Ripke S, Stahl EA, Starnawska A, Anjorin A; M. R.C.Psych, Corvin A, Sanders AR, Forstner AJ, Reif A, Koller AC, Świątkowska B, Baune BT, Müller-Myhsok B, Penninx BWJH, Pato C, Zai C, Rujescu D, Hougaard DM, Quested D, Levinson DF, Binder EB, Byrne EM, Agerbo E; Dr.Med.Sc, Streit F, Mayoral F, Bellivier F, Degenhardt F, Breen G, Morken G, Turecki G, Rouleau GA, Grabe HJ, Völzke H, Jones I, Giegling I, Agartz I, Melle I, Lawrence J; M.R.C.Psych, Walters JTR, Strohmaier J, Shi J, Hauser J, Biernacka JM, Vincent JB, Kelsoe J, Strauss JS, Lissowska J, Pimm J; M.R.C.Psych, Smoller JW, Guzman-Parra J, Berger K, Scott LJ, Jones LA, Azevedo MH, Trzaskowski M, Kogevinas M, Rietschel M, Boks M, Ising M, Grigoroiu-Serbanescu M, Hamshere ML, Leboyer M, Frye M, Nöthen MM, Alda M, Preisig M, Nordentoft M, Boehnke M, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Pato MT, Renteria ME, Budde M; Dipl.-Psych, Weissman MM, Wray NR, Bass N; M.R.C.Psych, Craddock N, Smeland OB, Andreassen OA, Mors O, Gejman PV, Sklar P, McGrath P, Hoffmann P, McGuffin P, Lee PH, Mortensen PB, Kahn RS, Ophoff RA, Adolfsson R, Van der Auwera S, Djurovic S, Kloiber S, Heilmann-Heimbach S, Jamain S, Hamilton SP, McElroy SL, Lucae S, Cichon S, Schulze TG, Hansen T, Werge T, Air TM, Nimgaonkar V, Appadurai V, Cahn W, Milaneschi Y; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; Bipolar Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Fanous AH, Kendler KS, McQuillin A, Lewis CM. GWAS of Suicide Attempt in Psychiatric Disorders and Association With Major Depression Polygenic Risk Scores. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:651-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, Li T, Ma C, Xu G, Yin H, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Huang Z, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yan J, Ding H, Yu Y, Kou C, Shen Z, Jiang L, Wang Z, Sun X, Xu Y, He Y, Guo W, Jiang L, Li S, Pan W, Wu Y, Li G, Jia F, Shi J, Shen Z, Zhang N. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:981-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 105.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rice F, Riglin L, Lomax T, Souter E, Potter R, Smith DJ, Thapar AK, Thapar A. Adolescent and adult differences in major depression symptom profiles. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Health Quality Ontario. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2016;16:1-66. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Croarkin PE, MacMaster FP. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Adolescent Depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28:33-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lefaucheur JP, Aleman A, Baeken C, Benninger DH, Brunelin J, Di Lazzaro V, Filipović SR, Grefkes C, Hasan A, Hummel FC, Jääskeläinen SK, Langguth B, Leocani L, Londero A, Nardone R, Nguyen JP, Nyffeler T, Oliveira-Maia AJ, Oliviero A, Padberg F, Palm U, Paulus W, Poulet E, Quartarone A, Rachid F, Rektorová I, Rossi S, Sahlsten H, Schecklmann M, Szekely D, Ziemann U. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): An update (2014-2018). Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131:474-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 501] [Cited by in RCA: 1449] [Article Influence: 241.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Fried EI, Nesse RM. Depression sum-scores don't add up: why analyzing specific depression symptoms is essential. BMC Med. 2015;13:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 388] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | American Psychiatric Association; DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. |

| 9. | Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2163-2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 660] [Cited by in RCA: 729] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim KM, Lee KH, Kim H, Kim O, Kim JW. Symptom clusters in adolescent depression and differential responses of clusters to pharmacologic treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;172:59-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Siddiqi SH, Taylor SF, Cooke D, Pascual-Leone A, George MS, Fox MD. Distinct Symptom-Specific Treatment Targets for Circuit-Based Neuromodulation. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:435-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kaster TS, Downar J, Vila-Rodriguez F, Baribeau DA, Thorpe KE, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Differential symptom cluster responses to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment in depression. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;55:101765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen H, Hu X, Gao J, Han H, Wang X, Xue C. Early Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Combined With Sertraline in Adolescents With First-Episode Major Depressive Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:853961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Seemüller F, Schennach R, Musil R, Obermeier M, Adli M, Bauer M, Brieger P, Laux G, Gaebel W, Falkai P, Riedel M, Möller HJ. A factor analytic comparison of three commonly used depression scales (HAMD, MADRS, BDI) in a large sample of depressed inpatients. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Murtagh F, Legendre P. Ward’s Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering Method: Which Algorithms Implement Ward’s Criterion? J Classif. 2014;31:274-295. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Pellegrini M, Zoghi M, Jaberzadeh S. Cluster analysis and subgrouping to investigate inter-individual variability to non-invasive brain stimulation: a systematic review. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29:675-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dalmaijer ES, Nord CL, Astle DE. Statistical power for cluster analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2022;23:205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shafer AB. Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:123-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 568] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chekroud AM, Gueorguieva R, Krumholz HM, Trivedi MH, Krystal JH, McCarthy G. Reevaluating the Efficacy and Predictability of Antidepressant Treatments: A Symptom Clustering Approach. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:370-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tokuoka H, Takahashi H, Ozeki A, Kuga A, Yoshikawa A, Tsuji T, Wohlreich MM. Trajectories of depression symptom improvement and associated predictor analysis: An analysis of duloxetine in double-blind placebo-controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2016;196:171-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hieronymus F, Emilsson JF, Nilsson S, Eriksson E. Consistent superiority of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors over placebo in reducing depressed mood in patients with major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:523-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Uher R, Maier W, Hauser J, Marusic A, Schmael C, Mors O, Henigsberg N, Souery D, Placentino A, Rietschel M, Zobel A, Dmitrzak-Weglarz M, Petrovic A, Jorgensen L, Kalember P, Giovannini C, Barreto M, Elkin A, Landau S, Farmer A, Aitchison KJ, McGuffin P. Differential efficacy of escitalopram and nortriptyline on dimensional measures of depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:252-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bondar J, Caye A, Chekroud AM, Kieling C. Symptom clusters in adolescent depression and differential response to treatment: a secondary analysis of the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:337-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | De Risio L, Borgi M, Pettorruso M, Miuli A, Ottomana AM, Sociali A, Martinotti G, Nicolò G, Macrì S, di Giannantonio M, Zoratto F. Recovering from depression with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhao Y, He Z, Luo W, Yu Y, Chen J, Cai X, Gao J, Li L, Gao Q, Chen H, Lu F. Effect of intermittent theta burst stimulation on suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in adolescent depression with suicide attempt: A randomized sham-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2023;325:618-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/