Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.110653

Revised: July 7, 2025

Accepted: October 15, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 169 Days and 1.6 Hours

Excessive video game use, recognized as internet gaming disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition and Gaming Disorder in International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, has raised concerns re

To analyze the association between internet gaming disorder and social in

The review examined 14 observational studies published between 2000 and 2025. It assessed the frequency and quality of face-to-face interactions, the shift towards online socialization, and the methodological quality of the included studies.

The findings generally indicate that gaming addiction is associated with a decrease in the frequency of offline social interaction. Addicted gamers reported spending less time with family and friends and experiencing increased isolation. Furthermore, the quality of social relationships appeared poorer, with addicted gamers reporting higher levels of loneliness, lower social support, and decreased relationship satisfaction. While online social interactions increased, they did not fully compensate for the loss of real-world connections.

This review highlights the potential of gaming addiction to negatively impact overall social lives, emphasizing the necessity for interventions focused on pro

Core Tip: This review of observational studies (2000-2025) reveals a significant association between internet gaming dis

- Citation: Byeon H. Impact of video game addiction on social interaction: An observational review examining loneliness, social anxiety, and social activity. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 110653

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/110653.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.110653

Excessive use of video games has raised concerns about its impact on mental health and social development[1,2]. It has now been explicitly recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as “internet gaming disorder (IGD)” needing “further study” and in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Re

A number of studies have reported an association between IGD and social interaction[8-14]. For instance, existing research[8-11] has correlated pathological or addictive gaming with adverse outcomes, including social isolation, elevated social anxiety, diminished social competence, and the replacement of offline relationships. Conversely, certain investigations[12,13] have highlighted the complex notion that online gaming may offer alternative modalities of socialization or coping mechanisms, such as the formation of in-game friendships. Consequently, this systematic review undertook a thorough analysis of observational study evidence concerning the relationship between encompassing IGD and social interaction outcomes. By comprehensively examining the results of various studies conducted since 2000 targeting Western and Asian (including Korean) populations, this review assessed whether gaming addiction has a significant association with a decrease in the frequency of face-to-face interactions, a deterioration in the quality of relationships (e.g., increased loneliness or lack of social support), or a shift from offline to online socialization. Furthermore, this study evaluated the methodological quality of the observational studies and highlighted potential biases. This study is further elaborated around the main analytical framework of interaction frequency, interaction quality, and the balance between offline and online socialization, providing a comprehensive overview of the multifaceted impact of gaming addiction on individuals’ overall social lives.

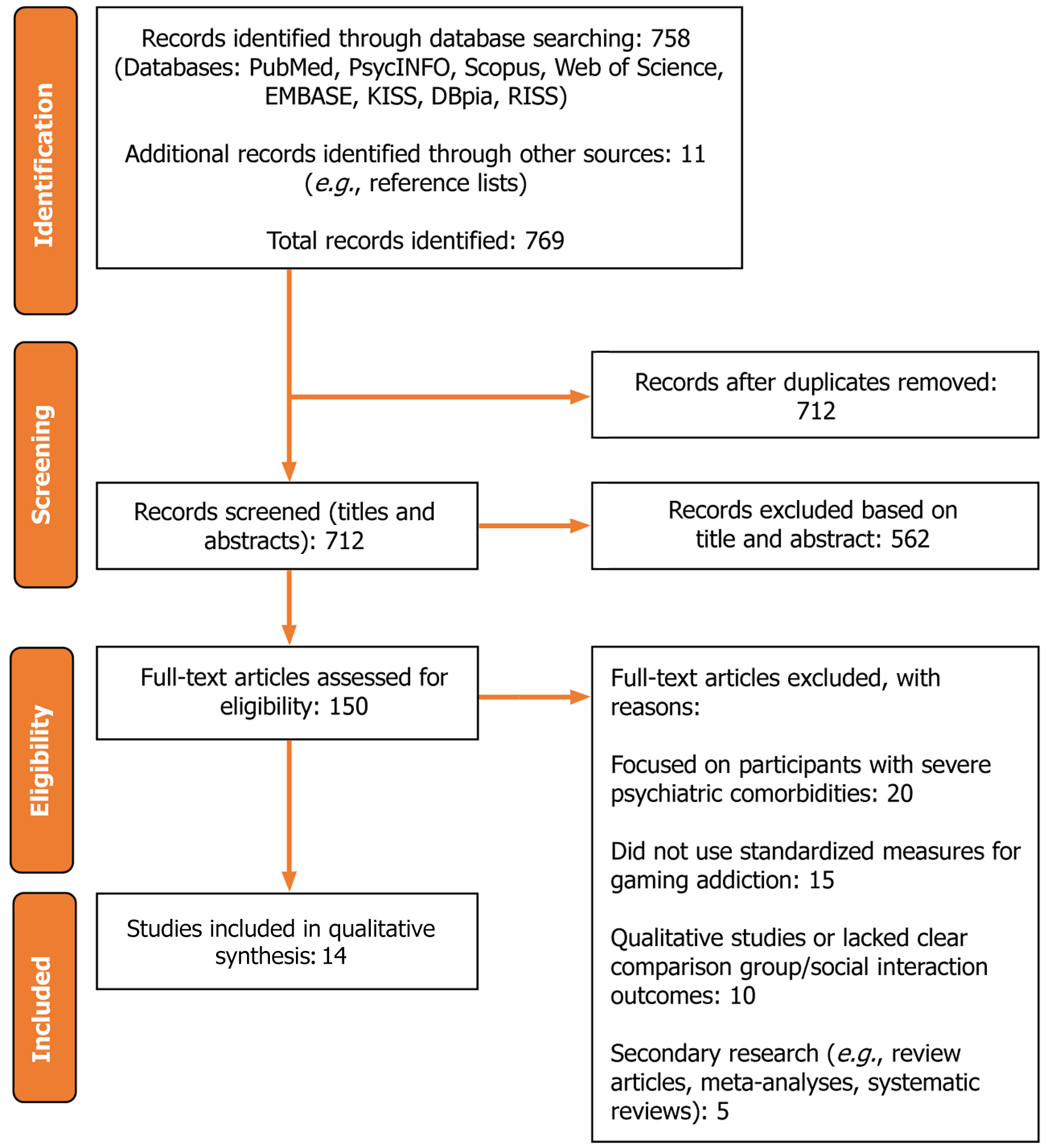

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, and it comprehensively searched relevant literature published up to May 31, 2025. The study was limited to literature written in English and Korean, and the following databases were utilized: International databases including PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science, and EMBASE; and domestic databases including Korean Studies Information Service System, DBpia, and Research Information Sharing Service. When searching, Boolean operators were used to combine search terms, and the main keywords were as follows: Keywords related to gaming addiction were “video game addiction”, “internet gaming disorder”, and “problematic gaming”; keywords related to social interaction were “social interaction”, “social isolation”, “loneliness”, “social support”, “relationships”, and “social skills”. Additionally, the reference lists of relevant review articles were manually reviewed to identify studies that could be included in this research.

The literature selection criteria: (1) Studies employing an observational study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal cohort studies) were included; (2) Studies that quantitatively assessed video game addiction IGD using standardized diagnostic tools or validated scales were selected; (3) Studies that measured social interaction outcomes (e.g., frequency of offline social activities, quality of relationships, social skills, types of offline vs online interactions, etc.) were included; (4) Studies that reported the association between gaming addiction and social variables were selected; and (5) Peer-reviewed articles published in English or Korean from 2000 to 2025 were included.

The excluded criteria: (1) Studies focusing solely on participants with severe psychiatric comorbidities were excluded; (2) Studies that did not use standardized measures for gaming addiction were excluded; (3) Qualitative studies or studies without a clear comparison group or outcomes related to social interaction were excluded; and (4) Secondary research such as review articles, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews were excluded.

The retrieved literature was first screened to remove duplicates. Subsequently, two independent researchers reviewed the titles and abstracts to assess whether they met the predefined selection criteria. For the selected literature, the full texts were thoroughly reviewed to determine the final inclusion, and in cases where disagreements arose between the researchers, a third researcher mediated to reach a consensus. The literature selection process is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Finally, 14 observational studies were included in this review.

The following information was systematically extracted from each study ultimately included in this review. Basic study characteristics such as author names, year of publication, and country of origin were collected. Regarding study design and sample characteristics, the study design, sample size, and participants’ age and gender were extracted. Instruments used to assess gaming addiction, including DSM-based IGD criteria, the IGD Scale, and the Game Addiction Scale, were noted. Measures of social interaction, such as the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale, Social Support Questionnaire, and Social Anxiety Inventory, were also extracted. Key findings, including effect sizes, correlation coefficients, and between-group differences, were recorded. The data extraction process was conducted independently by two researchers, with discrepancies in extracted information resolved through discussion and consensus.

The overall quality of the included studies and the risk of potential bias were evaluated using a modified assessment tool based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)[15]. The NOS assessment criteria comprise three main domains: Selection, Comparability, and Outcome. Within the Selection domain, the representativeness of the sample, the non-response rate, and the reliability and validity of the exposure (gaming addiction) measurement tools were assessed. The Comparability domain evaluated whether major confounding variables, such as age and gender, were controlled for in the study design or analysis. Finally, the Outcome domain assessed the reliability and validity of the social interaction outcome measures, as well as the clarity and appropriateness of the statistical analyses. Quality ratings were categorized based on the total score as good (7-9 points), fair (4-6 points), and poor (0-3 points). A “good” rating indicates studies with sound research design and methodology and a low risk of bias. A “fair” rating denotes studies with some limitations but that generally provide reliable results. A “poor” rating signifies studies with significant limitations in their design or methodology, warranting caution in the interpretation of their findings. The assessment of the studies included in this review revealed that most adopted a cross-sectional design, limiting the inference of causal relationships, and that data collection primarily relied on self-report questionnaires, potentially introducing response bias. These limitations were carefully considered when interpreting the findings of this review.

This systematic review included a total of 14 observational studies, of which 11 were cross-sectional[1,2,4-14] and 3 were longitudinal[3]. Ten studies were published in English[3-8,10,12-14], and four were published in Korean[1,2,9,11]. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of each study.

| Ref. | Country | Design and sample | Age (years) | Male (%) | Gaming addiction measure | Social outcome measure | Analysis |

| Limone et al[1], 2023 | South Korea | Cross-sectional; n = 1008 high school students | About 16 (adolescents) | 50% | Game Addiction Scale (Korean, self-report) | Perceived Social Support Scale | SEM (mediation model) |

| Tse et al[2], 2025 | South Korea | Cross-sectional; n = 930 middle school boys | 13-15 (teens) | 100% | Online Game Addiction Scale (obsessive vs harmonious passion) | Social Anxiety Scale; Social Skills and Hostility Scales | SEM (path analysis) |

| Gentile et al[3], 2011 | Singapore | Longitudinal (2-year); n = 3034 schoolchildren | 8-12 (at baseline) | 75% | DSM-IV/APA-based Pathological Gaming Criteria | Social Phobia symptoms (self-report); academic and other outcomes | Logistic and longitudinal regression |

| Mentzoni et al[4], 2011 | Norway | Cross-sectional (national survey); n = 816 adults | 16-40 (mixed adults) | 56% | PVP | Life Satisfaction Rating; Anxiety and Depression Scales | Correlation; group comparison |

| Wei et al[5], 2012 | Taiwan | Cross-sectional (online survey); n = 722 online gamers | 21.8 ± 4.9 | 83% | CIAS - gaming use subset | SPIN; DSSS | Pearson correlation; linear regression |

| Kök Eren and Örsal[6], 2018 | Turkey | Cross-sectional; n = 205 4th grade children | 9-10 (children) | 49% | Computer Game Addiction Scale for Children (21-item) | UCLA Loneliness Scale | Spearman correlation (r) |

| Adams et al[7], 2019 | Australia | Cross-sectional (pilot); n = 125 emergent adults | About 19-25 (young adults) | 50% | IGDS | Family cohesion (moderator); social anxiety | Pearson correlation |

| Tham et al[8], 2020 | United States | Cross-sectional; n = 361 university students (including gamers) | Mean about 20 (young adults) | 71% | Gaming Disorder Test (WHO-based) - “Problematic Gaming” | Multidimensional social support: Real-world vs in-game support | Path analysis (structural) |

| Jeong and Kim[9], 2020 | South Korea | Cross-sectional; about 300 adolescents | About 15-17 | 50% | K-IGA | Peer relationship quality; social anxiety | Regression, moderation |

| Guo et al[10], 2024 | China | Cross-sectional; n = 479 university students | Mean about 19.5 | 46% | DSM-5 IGD Scale (9-item) | Social Isolation Subscale (Self-Compassion Scale) | Pearson correlation; mediation (PROCESS) |

| Ko et al[11], 2024 | South Korea | Cross-sectional (national survey); n = 2764 adults (18-49) | 18-49 (adult gamers) | 67% | Structured Clinical Interview for IGD (DSM-5) | Perceived Loneliness and Social Isolation (single-item) | Logistic regression |

| Prince et al[12], 2023 | India | Cross-sectional; n = 200 undergraduates (1st year) | Mean about 18-19 | 84% | Self-reported Gaming Addiction Questionnaire | Time spent with family/friends (self-report); perceived social isolation while gaming (single-item) | Descriptive stats (%, χ²) |

| Lo et al[13], 2005 | Taiwan | Cross-sectional; n = 174 MMORPG players | Mean about 17 (teens) | 69% | Online gaming use (hours/week) - not diagnostic | Social anxiety (Chinese Social Anxiety Scale); offline vs online friends count | t-tests, correlation |

| Colwell and Payne[14], 2000 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional; n = 204 adolescents | 12-14 (school) | 52% | Gaming frequency and preference (no formal tool) | Self-esteem Scale; Social Isolation Concerns (questionnaire) | Pearson correlation |

Firstly, the sample sizes varied from studies with smaller cohorts of university or secondary school students (about 200-500)[5-7,9,10,12-14] to large-scale national surveys (n > 800)[1,4,11] and a longitudinal cohort study that tracked over 3000 adolescents[3]. Secondly, seven studies were conducted in East Asia (China, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore)[1-3,5,9-11], two in the Middle East/Europe (Turkey, Norway)[4,6], one in North America (United States)[8], and one in India[12]. Some research was also conducted in Australia and Europe[7]. Thirdly, the mean age of participants ranged from chil

Overall, the quality of the included studies was rated as moderate. Many studies employed self-report questionnaires for both gaming addiction and social behaviors, which may introduce common method bias and social desirability effects[1-14]. Furthermore, 11 out of 14 studies[1,2,4-14] utilized a cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to establish causal relationships. However, the longitudinal study by Gentile et al[3] strengthened the temporal precedence, demonstrating that gaming addiction predicted subsequent social problems.

The representativeness of the samples varied across studies. While two national surveys and a nationwide school-based study enhanced generalizability[1,4,11], other studies[5-7,9,10,12-14] used convenience samples of students or online gamers, potentially overrepresenting highly engaged participants. Notably, most studies[3,5,7-11] adjusted for or considered confounding variables such as age, gender, and co-occurring mental health symptoms (e.g., depression) in their analyses. Reported reliability of the measurement tools was high[1-14], with Cronbach’s α values for both gaming addiction and social scales generally at or above 0.8.

Assessment using the NOS criteria (Table 2) indicated a risk of bias in participant selection in some studies[5-7,9,10,12-14]. For instance, many samples excluded non-student young adults[5,7,9,10,12], and there was a lack of blinding or objective measurement in the assessment of social interaction outcomes[12-14]. Despite these limitations, all included studies met standardized measurement criteria and provided a consistent body of evidence (Table 2).

| Ref. | Selection (0-4 points) | Comparability (0-2 points) | Outcome (0-3 points) | Total score (0–9 points) | Quality rating |

| Limone et al[1], 2023 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Good |

| Tse et al[2], 2025 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Good |

| Gentile et al[3], 2011 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | Good |

| Mentzoni et al[4], 2011 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Fair |

| Wei et al[5], 2012 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Fair |

| Kök Eren and Örsal[6], 2018 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Fair |

| Adams et al[7], 2019 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Fair |

| Tham et al[8], 2020 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Good |

| Jeong and Kim[9], 2020 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Good |

Several studies[1-3,6,9-14] directly examined whether individuals with gaming addiction spend less time in face-to-face social activities or experience social withdrawal. The evidence suggests that excessive gaming often displaces offline socializing.

In a survey of 200 college freshmen in India[12], 71.4% of students agreed or strongly agreed that online gaming had consumed time they would otherwise spend with family or friends. Over half (58.1%) acknowledged that gaming reduced their personal time with loved ones[12]. Similarly, nearly half (49.5%) of these students felt “socially isolated” while playing (with only about 18% disagreeing)[12]. This indicates a perceived reduction in in-person interaction during gaming, even among young adults aware of the issue.

A Korean high school study by Limone et al[1] found that gaming addiction was significantly associated with lower perceived social support from family and friends. In that structural model, higher game addiction scores predicted diminished social support, which in turn led to more behavioral problems, suggesting that addicted adolescents may be socially withdrawing or losing supportive connections (social support acted as a mediating factor)[1].

National survey data from Korea similarly reported that adult IGD cases had elevated feelings of social isolation - these individuals were more likely to report having no close friends or confidants in real life[11]. IGD was correlated with being unmarried and unemployed in that sample, indirectly reflecting fewer social interactions[11].

In younger populations, parent-reported social interaction frequency also appeared negatively impacted. A Turkish study of children[6] noted that excessive gaming can slow social development - children with higher game addiction scores were described as spending less time in face-to-face play and having lower peer engagement[6].

However, not all evidence was one-sided. A few studies[7,8,13] imply that moderate gaming, especially when socially motivated, may not reduce - and can even facilitate -social contacts (albeit often virtual ones). Similarly, Lo et al[13] ob

In summary, most addicted or high-use gamers reduce offline social frequency, reporting sacrificed family/friend time and increased isolation[1,6,11,12]. A minority of studies[7,8,13] suggest social gaming contexts can provide interaction (online or co-play) that partially substitutes for offline contact. Nonetheless, the net effect in the addicted group appears to be less face-to-face socializing[1,6,11-14]. This reduction in interaction frequency is one pathway by which gaming addiction can impair social health.

A consistent finding across studies[1-14] is that IGD correlates with poorer quality of social relationships, manifesting as higher loneliness, lower social support, and strained interpersonal ties.

Multiple studies[6,10,11] linked problematic gaming to feeling lonely. In a cross-sectional study of 205 Turkish children[6], the correlation between game addiction scores and loneliness was r = 0.36 (P < 0.001), indicating that children who were more addicted to games felt significantly more lonely. In fact, loneliness levels in the high-addiction group were markedly elevated. This aligns with Korean survey data where gaming disorder was associated with self-reported loneliness and dissatisfaction with social life[11]. The direction of this association is hard to untangle in cross-sectional data - lonely individuals may retreat into games, and heavy gaming can further alienate them - but the longitudinal evi

Social support refers to the availability of help or companionship from others. Two studies[1,8] explicitly examined this. Limone et al[1] found gaming-addicted high schoolers had significantly lower perceived support from parents, peers, and teachers. Tham et al[8] extended this by differentiating “real-world” vs “in-game” social support in a United States college sample. They reported that problematic gaming was linked to decreased real-world support (β significant), even as in-game support (e.g., guild/clan friends) increased. Crucially, only real-world support predicted better mental health; in-game support did not mitigate depression/anxiety associated with gaming[8]. Thus, the quality of social resources for addicted gamers is poorer - support from real friends/family wanes - and purely online friendships might not provide the same emotional benefits.

Several studies[4,7,11] indirectly measured this via life satisfaction or family harmony. In Mentzoni et al’s Norwegian survey[4], problem gamers had significantly lower life satisfaction scores than non-problem gamers. While life satisfaction is multifaceted, reduced satisfaction often ties to social well-being. Similarly, an Australian study (Adams et al[7] in 2019) noted that among emerging adults, IGD symptoms were associated with lower family cohesion (though that study focused on family environment as a moderator). Qualitatively, families of addicted gamers frequently report conflict and eroded communication, indicating a toll on relationship quality (as echoed in multiple case reports, though those are beyond our scope).

Beyond subjective feelings, gaming addiction may affect how individuals relate to others. A Korean study by Tse et al[2] found that adolescents with higher game addiction had lower social skills (measured by a standardized social skills rating) and higher hostility, which in turn worsened their relationships and social anxiety. In their structural equation modeling model, game addiction led to social skill deficits (e.g., poorer communication or cooperation abilities) which partly mediated increased social anxiety and deteriorating peer relations[2]. This suggests addiction might stunt the development of interpersonal skills (perhaps due to spending time in relatively asocial gaming tasks or toxic online environments) - a finding consistent with other research noting poor social competence among heavy gamers[2,3,9].

Across these studies[1-14], a robust theme is that addicted gamers often experience poorer social well-being: They feel less connected, less supported, and less satisfied socially. Many fulfill IGD criteria such as “jeopardizing relationships or opportunities to continue gaming”, reflecting the real-life social cost. Encouragingly, Gentile’s longitudinal data[3] show these social deficits can improve if the gaming addiction is addressed: When formerly addicted youth stopped meeting criteria, their social phobia and loneliness scores dropped back down[3]. This underscores that the social impairments are not necessarily permanent, but rather linked to the state of addiction.

One nuanced question is whether gamers with addiction replace offline interactions with online ones, and how those compare. Evidence indicates that many do shift towards online socialization, but this is not equivalently beneficial and can form a vicious cycle.

Addicted gamers often report that socializing within the game feels easier or more rewarding than face-to-face inte

Tham et al[8] provide a clear illustration: Problem gamers did report increased in-game support (friends made through gaming), but simultaneously their real-world support declined. Moreover, only real-world connections buffered them from emotional distress; the support from online gaming friends did not translate into reduced depression or anxiety[8]. This suggests that while online interactions can be enjoyable and even emotionally meaningful, they often lack certain qualities of face-to-face support (physical presence, tangible help, deep emotional bonds forged over time). Thus, relying on online networks alone may leave psychosocial needs unmet.

In severe cases (clinical gaming addiction), individuals may enter a state of near-complete social withdrawal from the offline world. Dong et al[16] have related this to the concept of “hikikomori” (acute social withdrawal), which in some cases is facilitated by immersive gaming. Case studies exist of youths who stopped attending school or work, spending all time gaming and interacting only via internet - a stark illustration of online interaction completely replacing offline interaction[17,18]. While rare, such cases highlight the extreme of the spectrum where gaming addiction leads to almost total loss of real-life social functioning. Most observational studies in our review did not focus on such extreme cases, but they capture the gradient: As gaming involvement rises, offline engagement falls[1,3,10,13].

It’s worth noting that in cultures where online gaming is very common (e.g., South Korea), there are also structured opportunities for face-to-face social gaming (PC bang gaming cafés, e-sports clubs). This might mitigate the isolation for some; for example, one Korean study[9] found that strong peer support (e.g., friends gaming together or parents moderating gaming) could buffer against social problems, even if game time was high. Family or peer co-play might maintain some offline social contact. However, these nuances were not extensively covered in the studies reviewed, and the overall trend still pointed to decreased in-person interaction in those meeting addiction criteria[1,2,9,11].

In conclusion, while addicted gamers often increase online social interaction (gaming communities, chats), this does not fully compensate for the loss of offline interaction quality[8,10,13]. The type of interaction shifts – from richer in-person contexts to more narrow, game-focused communication. This shift can reinforce the addiction (since the game becomes the primary social outlet) and can create a feedback loop: Feeling socially isolated - > gaming more for social connection - > further neglect of real-life relationships, and so on[1,3,8,9,10,13]. Effective interventions may need to break this cycle by reconnecting individuals to real-world social activities.

Integrating the above results, we highlight several thematic findings. Firstly, addicted gamers are lonelier and more socially anxious. Virtually every study reported higher loneliness or social anxiety associated with gaming addiction[1-3,5,6,9,10,13]. The link with social anxiety is particularly notable - problem gamers often fear face-to-face social situations and may retreat into gaming where interactions feel safer[2,5,9,13]. In longitudinal data, increased social phobia was an outcome of prolonged gaming addiction, not merely a precursor[3]. This suggests that social avoidance can be both a cause and consequence of excessive gaming.

Secondly, real-life social networks deteriorate. Addicted individuals report shrinking offline social circles, less time with friends/family, and lower perceived support[1,7-9,11,12]. Several studies found that controlling for depression or other factors, gaming addiction independently predicted poor social support and relationship strain[1,3,4,7,9]. The quality of interactions (e.g., trust, intimacy) likely suffers as well - though not measured directly in all studies, it is implied by increased conflict and decreased cohesion in families of gamers[3,7].

Thirdly, there is a displacement of offline by online interaction. A consistent pattern is that social needs start to be met via the game (chatting with guildmates, etc.) rather than in person[8,10,12,13]. While this can provide short-term satisfaction and a sense of community, it often lacks depth and stability, and it can further estrange gamers from “meatspace” relationships. In effect, online socialization in games becomes a double-edged sword - it sustains the gamer emotionally to some degree, but also perpetuates the gaming behavior and neglect of real life[8,10,13].

Fourthly, diminished social skills and increased hostility were observed. Some studies delved into personality

Fifthly, heterogeneity and moderating factors exist. Not all gamers experience social harm equally. Moderator analyses showed, for example, that those living alone were at special risk - loneliness had a stronger effect on driving gaming problems in individuals living by themselves[9,11]. This suggests that lacking day-to-day companionship (roommates or family) can exacerbate the social toll of gaming addiction. On the other hand, factors like family support, supervised gaming, or peer group gaming can buffer negative effects (e.g., a supportive family might prevent a lonely teen from fully withdrawing into games)[1,2,9]. Cultural context also matters: Social stigma around gaming can isolate gamers more, whereas in some environments gaming is a common social hobby (possibly reducing isolation if done together)[1,2,9,11]. These nuances aside, the overarching trend remains that unhealthy gaming patterns erode healthy social functioning.

This systematic review of observational studies provides robust evidence that IGD is associated with decreased and impaired social interaction across various domains. Individuals meeting criteria for gaming disorder tend to spend less time in offline social activities, report greater loneliness and social anxiety, and have lower quality relationships and support networks compared to their peers[1,2,3,8,10,11]. Notably, longitudinal studies suggest that these social dif

Our review also highlights the mechanisms through which gaming addiction may impact social life. Addicted gamers often seek social rewards within games (e.g., teamwork, chatting, virtual communities), substituting for offline rela

These findings align with prior literature on internet and gaming addiction. Numerous earlier studies[14,19] noted negative correlations between excessive gaming and social withdrawal, as well as reduced peer engagement. Our review updates and extends this knowledge by demonstrating that even in the context of modern online games with significant social components, the net effect of addiction is detrimental to real-world social well-being. Zhuang et al’s meta-analysis[20] has also concluded that IGD is associated with lower social competence and greater loneliness across various age groups. Furthermore, the inclusion of Korean studies in our review reinforces that these patterns hold even in cultures with high rates of game usage; for instance, Korean adolescents with gaming addiction displayed significantly lower social adjustment and more interpersonal problems[1,2,9,11].

It is important to note that not all studies have found consistently negative effects, and some research[4,13] has documented that moderate, controlled gaming can coexist with healthy social lives or even enhance social connections through shared activity. This nuance suggests the need to distinguish between problematic and non-problematic gaming[21]. Intensity and control are likely key factors - socially gaming with friends for an hour or two a day is different from gaming for 8-10 hours alone or with anonymous online partners. The former may be a social hobby, while the latter can contribute to social isolation and dysfunction. Thus, it is the addiction - the loss of control, the prioritization over other activities, and the continuation despite negative consequences - that consistently yields poor social outcomes, rather than gaming itself.

In this study, the evidence reviewed underscores the importance of assessing social functioning in individuals with gaming disorder. Clinicians treating IGD should recognize that these patients are at heightened risk for social isolation, low support, and interpersonal conflict. Interventions may need to incorporate social skills training, family therapy, or group therapy to rebuild social connections and competence[22]. Given that many addicted gamers find solace or comfort in online social realms[23], treatment could also leverage this - for example, controlled peer support groups (offline or online) for gamers could provide a bridge back to real-world relationships. These findings also have preventative implications: Parents and educators should monitor not only the duration of gaming but also its impact on a child’s social life. Early warning signs may include withdrawal from friends, loss of interest in previously enjoyed social activities, and decreased communication with family[8].

Using the NOS criteria, most included studies were rated as being of moderate quality (5-7 points out of 9 points) in this systematic review study. Common reasons for lower scores were a lack of representativeness and attrition (mostly absent follow-up). Encouragingly, the measurement tools in almost all studies were robust, increasing confidence in the reliability of the observed relationships. Future research should aim for more prospective designs, tracking social functioning as gamers develop and (hopefully) resolve problematic gaming to better delineate cause and effect. Fur

This systematic review is limited by the quality of available research. Firstly, using the NOS criteria, most included studies were rated as being of moderate quality (5-7 points out of 9 points). Common reasons for lower scores were a lack of representativeness and attrition (mostly absent follow-up). This moderate quality underscores the need for caution when implementing widespread practical recommendations based solely on these findings. Secondly, most included studies adopted a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to draw definitive causal inferences. The possibility of reverse causality cannot be excluded in some associations (e.g., individuals who are socially anxious or lonely may be more drawn to gaming as an escape). While longitudinal evidence helps to mitigate this, it does not entirely eliminate the possibility of bidirectionality. This limitation makes it challenging to definitively establish whether interventions targeting gaming addiction will directly lead to improved social interaction, or if other underlying factors need to be addressed concurrently. Thirdly, cultural differences in the meaning of social interaction and gaming were not explored in sufficient depth in this review. Although we attempted to enhance generalizability by including studies from various countries, there may be unique cultural factors (such as familial punishment for gaming) that exacerbate social withdrawal in certain cultural contexts. The lack of in-depth cultural exploration means that our understanding of how cultural norms influence the observed patterns and the effectiveness of potential culturally-specific interventions remains limited. Fourthly, there is a potential for publication bias. Studies that found strong negative social impacts of gaming are more likely to be published, whereas studies reporting null or positive social findings are relatively scarce (with some exceptions). However, the consistency of findings across various settings enhances the credibility of the conclusions drawn in this review. Despite this consistency, the potential for publication bias suggests that the full spectrum of the relationship between gaming and social interaction might not be completely represented, which could affect the comprehensiveness of our practical recommendations. Fifthly, future research should employ more prospective designs to track social functioning as gamers develop and (hopefully) recover from problematic gaming, which would allow for a clearer distinction between cause and effect. Such prospective studies are crucial for developing more effective and targeted long-term practical strategies. Lastly, qualitative research could provide valuable insights into the subjective social experiences of addicted gamers, such as how they perceive online vs offline friendships.

Synthesizing the findings of this review, the observational study evidence accumulated over the past two decades converges on the conclusion that IGD has a detrimental impact on healthy social interaction. Individuals with gaming addiction tend to withdraw from real-world interactions, experience greater loneliness and social anxiety, and suffer a decline in the quality of their relationships and support systems. While online games may incorporate social elements, these do not fully compensate for the reduction in offline social engagement and may, in fact, exacerbate a negative cycle of social avoidance. The results of this study underscore the importance of comprehensively addressing the social environment of gamers when implementing therapeutic or preventive interventions for IGD. Specifically, rebuilding offline relationships, improving social skills, and finding a balance between virtual and real-world interactions are crucial. Given the profound link between human well-being and social connection, the social dysfunction associated with gaming disorder is a serious concern. By recognizing and actively intervening in these social aspects, it is possible to more effectively assist individuals in overcoming gaming addiction and restoring meaningful interpersonal relationships.

| 1. | Limone P, Ragni B, Toto GA. The epidemiology and effects of video game addiction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2023;241:104047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tse N, Pang NSN, Wang X, Li Y, Lo CKM, Yang X. The roles of binge gaming in social, academic and mental health outcomes and gender differences: A school-based survey in Hong Kong. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0327365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gentile DA, Choo H, Liau A, Sim T, Li D, Fung D, Khoo A. Pathological video game use among youths: a two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e319-e329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 716] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mentzoni RA, Brunborg GS, Molde H, Myrseth H, Skouverøe KJ, Hetland J, Pallesen S. Problematic video game use: estimated prevalence and associations with mental and physical health. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:591-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wei HT, Chen MH, Huang PC, Bai YM. The association between online gaming, social phobia, and depression: an internet survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kök Eren H, Örsal Ö. Computer Game Addiction and Loneliness in Children. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47:1504-1510. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Adams BLM, Stavropoulos V, Burleigh TL, Liew LWL, Beard CL, Griffiths MD. Internet Gaming Disorder Behaviors in Emergent Adulthood: a Pilot Study Examining the Interplay Between Anxiety and Family Cohesion. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2019;17:828-844. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tham SM, Ellithorpe ME, Meshi D. Real-world social support but not in-game social support is related to reduced depression and anxiety associated with problematic gaming. Addict Behav. 2020;106:106377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jeong J, Kim J. The Effects of the Adlerian Theory-Based Career Counseling Program on the Career Self-Efficacy and Career Maturity Among Middle School Students. Korean J Youth Stud. 2020;27:1-31. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Guo Y, Yue F, Lu X, Sun F, Pan M, Jia Y. COVID-19-Related Social Isolation, Self-Control, and Internet Gaming Disorder Among Chinese University Students: Cross-Sectional Survey. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e52978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ko YM, Lee ES, Park S. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidities of internet gaming disorder and problematic game use: national mental health survey of Korea 2021. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1442224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Prince B X, Vimal Raj AR, Nazini N. Impact of online gaming addiction on social isolation among first-year Sathyabama undergraduate students: A study. Shodh Kosh: J Vis Perform Arts. 2023;4:331-339. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Lo SK, Wang CC, Fang W. Physical interpersonal relationships and social anxiety among online game players. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Colwell J, Payne J. Negative correlates of computer game play in adolescents. Br J Psychol. 2000;91 ( Pt 3):295-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [cited 11 June 2025]. Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. |

| 16. | Dong B, Li D, Baker GB. Hikikomori: A Society-Bound Syndrome of Severe Social Withdrawal. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;32:167-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kubo T, Horie K, Matsushima T, Tateno M, Kuroki T, Nakao T, Kato TA. Hikikomori and gaming disorder tendency: A case-control online survey for nonworking adults. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2024;78:77-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee EJ. A case study of Internet Game Addiction. J Addict Nurs. 2011;22:208-213. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lennon N, Yard E. Risk and protective factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Black female and male youth with depression symptoms - United States, 2004-2019. J Affect Disord. 2024;358:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhuang X, Zhang Y, Tang X, Ng TK, Lin J, Yang X. Longitudinal modifiable risk and protective factors of internet gaming disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Addict. 2023;12:375-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kristensen JH, Pallesen S, King DL, Hysing M, Erevik EK. Problematic Gaming and Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:675237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bore P, Nilsson S, Andersson M, Oehm K, Attvall J, Håkansson A, Claesdotter-Knutsson E. Effectiveness and Acceptability of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Family Therapy for Gaming Disorder: Protocol for a Nonrandomized Intervention Study of a Novel Psychological Treatment. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13:e56315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yildiz Durak H, Haktanir A, Saritepeci M. Examining the Predictors of Video Game Addiction According to Expertise Levels of the Players: The Role of Time Spent on Video Gaming, Engagement, Positive Gaming Perception, Social Support and Relational Health Indices. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2023;1-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/