Published online Nov 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i11.111593

Revised: July 13, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: November 19, 2025

Processing time: 123 Days and 18 Hours

Adolescents with an evening chronotype are at higher risk for mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. However, the mechanisms underlying this relationship are not well understood. Sleep disturbances and impaired social functioning may mediate this association.

To examine the mediating roles of sleep quality and social functioning in the relationship between chronotype and mental health in adolescents.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 381 adolescents (mean age 14.3 years; 61.9% male) using the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and Social Disability Screening Schedule. Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation analyses, and chain mediation analysis using the bootstrap method were performed.

Chronotype was significantly associated with both depression and anxiety. Sleep quality and social functioning significantly mediated these relationships. The indirect effect on depression was -0.52, accounting for 69.3% of the total effect. For anxiety, the indirect effect was -0.39, accounting for 79.3%. No significant direct effect of chronotype on depression or anxiety was found after accounting for the mediators.

Sleep quality and social functioning mediate the association between chronotype and adolescent mental health. These findings highlight the importance of addressing sleep disturbances and social functioning impairments in interventions aimed at improving mental well-being among adolescents with evening chronotypes.

Core Tip: This cross-sectional observational study investigated the indirect pathways linking chronotype to adolescent mental health. Using validated measures in 381 adolescents, we found that the relationship between evening chronotype and higher levels of depression and anxiety was fully mediated by poor sleep quality and impaired social functioning. This is the first study to establish a chain mediation model incorporating both sleep and social factors, emphasizing the importance of targeting sleep hygiene and social adjustment in interventions for youth mental health.

- Citation: Zhao XF, Bi YX, Xiao S, Lou ML, Zhu WL, Xing YR. Chronotype as a risk factor for adolescent depression and anxiety: The mediating roles of sleep and social functioning. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(11): 111593

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i11/111593.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i11.111593

Major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent mental health conditions in adolescents. Epidemiological studies indicate that approximately one in ten individuals aged 5-24 years experiences mental health disorders, contributing significantly to the global disease burden in this age group[1]. Given their high prevalence and impact on academic performance, social functioning, and overall well-being, understanding the underlying mechanisms of these conditions is crucial for developing effective interventions.

One potential factor influencing adolescent mental health is chronotype, defined as an individual’s preference for sleep timing and activity patterns, typically categorized into morning, intermediate, and evening types[2,3]. Adolescents with an evening chronotype are particularly vulnerable to developing emotional and behavioral problems. This group tends to experience sleep disturbances, poor academic performance, and heightened emotional distress, all of which contribute to mental health issues, including depression and anxiety[4,5]. However, while an evening chronotype is associated with these conditions, the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain poorly understood.

Anxiety disorders, frequently co-occurring with depression, are significant contributors to functional impairment among adolescents. Studies show that individuals with an evening chronotype exhibit higher levels of anxiety, which can exacerbate feelings of distress and impair social functioning[6]. Anxiety is not only a direct contributor to mental health issues but also influences sleep quality and social engagement, creating a complex cycle that can worsen mental well-being[7]. Despite these associations, the role of anxiety in the relationship between chronotype and adolescent mental health remains underexplored, warranting further investigation.

Two theoretical models provide insight into the potential mechanisms linking chronotype to mental health: The social zeitgeber theory and the dual process model of sleep regulation. The social zeitgeber theory posits that disruptions in social rhythms, such as sleep timing and social routines, can destabilize circadian rhythms, leading to mood disturbances[8]. Despite the growing recognition of chronotype as a potential risk factor for mental health disturbances, its precise role in adolescent mental health remains underexplored. This theory is particularly relevant to adolescents with an evening chronotype, as misalignment between biological rhythms and societal demands (e.g., school start times) may increase stress and emotional dysregulation.

Similarly, the dual process model of sleep regulation suggests that evening chronotype individuals experience a mismatch between their internal biological sleep needs and external societal demands, such as early school schedules[9]. This misalignment can lead to sleep deprivation, which in turn affects emotional regulation, cognitive function, and social interactions. Both theories emphasize the importance of understanding how chronotype influences mental health and suggest that interventions targeting sleep and social functioning may be crucial for improving outcomes in adolescents with evening chronotypes.

Adolescents are increasingly exposed to factors that disrupt sleep, including excessive screen time, academic stress, and social obligations[10]. These disruptions contribute to the high prevalence of sleep disorders, such as insufficient sleep duration, prolonged sleep onset latency, and delayed sleep phase syndrome[11]. Emerging evidence suggests that sleep quality mediates the relationship between chronotype and mental health, with evening chronotype being associated with poorer sleep and greater depressive symptoms[12]. While sleep disturbances are a recognized contributor to mental health disorders, they do not fully explain the relationship between chronotype and psychological outcomes[13], indicating the need to examine additional mediating mechanisms.

Social functioning, encompassing social cognition, interpersonal skills, and the ability to establish and maintain relationships, is another critical factor influencing adolescent mental health[14]. Studies suggest that evening-type individuals exhibit lower levels of daytime social engagement and impaired academic and social functioning[15]. Additionally, compromised mental health is associated with deficits in social functioning[16]. While previous research has examined the relationships between chronotype, sleep, and mental health independently, these factors likely interact in a complex manner. Our study builds upon this literature by exploring how these factors interact, rather than examining them in isolation. Understanding the potential mediating roles of sleep quality and social functioning is essential for identifying underlying mechanisms and informing targeted interventions to reduce the burden of adolescent mental health disorders. We hypothesized that poor sleep quality and impaired social functioning would mediate the relationship between evening chronotype and higher levels of depression and anxiety in adolescents.

This study employed a cluster sampling method and a cross-sectional survey design. A total of 10 survey sessions were conducted, during which 412 questionnaires were distributed. Of these, 381 valid responses were received, resulting in a valid response rate of 92.5%. Sample size was estimated based on a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) for mediation models, with statistical power of 0.80 and alpha of 0.05, which suggested a minimum of 146 participants. Our sample of 381 participants exceeded this threshold, allowing sufficient power for the planned analyses.

Prior to data collection, all participants provided informed consent after receiving a detailed explanation of the study’s objectives, potential benefits, and risks. They were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without penalty. As the participants were minors, informed consent was obtained from both the adolescents and their legal guardians. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The mean age of the participants was 14.34 ± 1.21 years, with an average educational duration of 8.73 ± 1.15 years. The sample included 236 males (61.9%) and 145 females (38.1%), with 13 participants (3.4%) being only children. Regarding personality traits, 94 participants (24.7%) were classified as introverted, 208 (54.6%) as ambiverted, and 79 (20.7%) as extroverted. Among the participants, 49 (12.9%) self-reported depression, while 44 (11.5%) reported suicidal ideation. Additionally, 32 participants (8.4%) reported a history of childhood trauma, and 18 participants (4.7%) had a family history of mental disorders.

Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire: The Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ-5) was used to assess chronotype by categorizing individuals based on their circadian rhythm preferences[17]. This five-item scale has a maximum score of 25, with items 1, 3, and 4 rated on a 1-5 scale, item 2 on a 1-4 scale, and item 5 on a 0, 2, 4, 6 scale. Higher scores indicate a greater morning preference. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the MEQ-5 was 0.79.

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: The 24-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) was used to assess depressive symptom severity[18]. Items are rated on a 0-2 or 0-4 scale, with higher scores indicating greater depression severity. The Cronbach’s α for the HAMD-24 in our sample was 0.91.

Hamilton Anxiety Scale: The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) was used to assess anxiety symptoms[19]. Each item is scored on a 0-4 scale, with higher total scores reflecting greater anxiety severity. The Cronbach’s α for the HAMA was 0.89.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to evaluate self-reported sleep disturbances[20]. It comprises 19 self-report items and 5 additional questions scored by a bed partner or roommate. In this study, only the self-reported items were analyzed. Each item is rated on a 0-4 scale, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. The PSQI consists of seven components: Subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The total score is the sum of these seven components, ranging from 0 to 21. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the PSQI was 0.83.

Social Disability Screening Schedule: The Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS) was used to assess the degree of social functioning impairment[21]. It consists of 11 items, with a total possible score of 22. For unmarried individuals, items 2 and 3 are excluded. Each item is scored on a 0-2 scale, with higher scores indicating greater social dysfunction. The Cronbach’s α for the SDSS in our sample was 0.87.

Data were processed and analyzed using SPSS 25.0 and the PROCESS macro. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analyses were conducted in SPSS 25.0. Mediation analysis was performed using the PROCESS macro (model 6)[22], employing the bootstrap method with 5000 resamples and a 95% confidence interval (CI). A mediation effect was considered statistically significant if the CI did not include zero. Assumptions for Pearson correlation (normality and linearity) were assessed prior to analysis. Statistical hypothesis testing was conducted using 95%CIs and P values, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Since all data in this study were self-reported by the same individuals, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess common method bias. An unrotated exploratory factor analysis of all questionnaire items revealed that the first principal component accounted for 29.2% of the total variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. This indicates that common method bias is not a significant concern in this study.

The mean scores and standard deviations for the study variables were as follows: MEQ-5 (13.92 ± 4.07), PSQI (5.79 ± 3.36), SDSS (2.49 ± 3.21), HAMD-24 (12.17 ± 11.49), and HAMA (10.22 ± 9.22). The descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Personality was assessed using a self-report question asking participants to classify themselves as introverted, ambiverted, or extroverted. The distribution of personality types among the participants was as follows: 94 individuals (24.7%) identified as introverted, 208 individuals (54.6%) as ambiverted, and 79 individuals (20.7%) as extroverted. We used a self-reported question to classify participants’ personality as introverted, ambiverted, or extroverted. However, we acknowledge that this method is unscientific and may lack reliability. As personality was not a primary variable in our study, we have decided to focus on chronotype, sleep quality, and social functioning as the main predictors of depression and anxiety.

| Variables | mean ± SD /n (%) |

| Gender (male) | 236 (61.9) |

| Age | 14.34 ± 1.21 |

| Body mass index | 22.65 ± 8.47 |

| Only child | 13 (3.4) |

| Personality | |

| Introverted | 94 (24.7) |

| Average | 208 (54.6) |

| Extroverted | 79 (20.7) |

| Years of education | 8.73 ± 1.15 |

| Depressed mood (yes) | 49 (12.9) |

| Suicidal ideation (yes) | 44 (11.5) |

| Family history | 18 (4.7) |

| Childhood trauma history | 32 (8.4) |

| MEQ-5 | 13.92 ± 4.07 |

| PSQI | 5.79 ± 3.36 |

| SDSS | 2.49 ± 3.21 |

| HAMD | 12.17 ± 11.49 |

| HAMA | 10.22 ± 9.22 |

Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess linear relationships among continuous variables. Prior to conducting the correlation, assumptions of normality and linearity were checked and met. Pearson correlation analysis indicated that MEQ-5 scores were negatively correlated with social function impairment, poor sleep quality, anxiety, and depression levels. Additionally, social function impairment was positively correlated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, and de

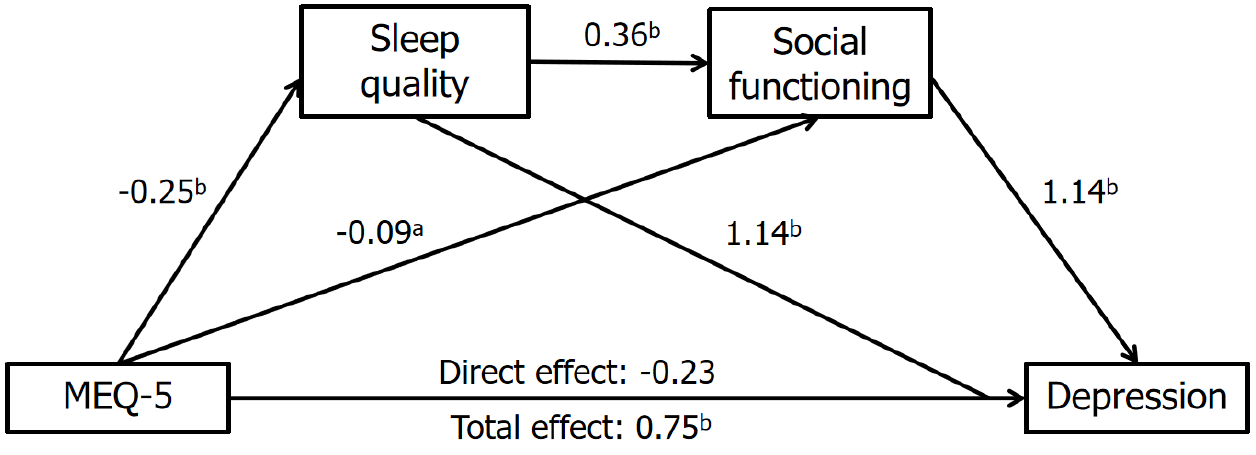

The study revealed significant correlations between MEQ-5 scores and social function impairment, sleep quality, anxiety, and depression levels, meeting the prerequisites for mediation effect testing. Using the SPSS PROCESS macro (model 6), we examined the mediating roles of sleep quality and social function in the relationship between chronotype and adolescent mental health, controlling for gender, age, and body mass index as covariates. The MEQ-5 score served as the independent variable, depression level as the dependent variable, and sleep quality and social function as chain me

| β | t | P value | 95%CI | |

| MEQ-5, sleep quality | -0.25 | -6.27 | < 0.001 | (-0.33 to -0.17) |

| MEQ-5, social functioning | -0.09 | -2.39 | 0.018 | (-0.17 to -0.02) |

| Sleep quality, social functioning | 0.36 | 7.48 | < 0.001 | (0.26-0.45) |

| MEQ-5, depression level | -0.23 | -1.94 | 0.053 | (-0.47 to 0.01) |

| Sleep quality, depression level | 1.14 | 7.34 | < 0.001 | (0.84-1.45) |

| Social functioning, depression level | 1.28 | 8.20 | < 0.001 | (0.98-1.59) |

The results indicated that the total indirect effect of sleep quality and social function on the relationship between chronotype and depression levels was -0.52, accounting for 69.3% of the total effect. The 95%CI did not include zero, confirming the significant mediating effect of sleep quality and social function in the association between chronotype and depression levels in adolescents. This mediation effect comprised three distinct indirect effect pathways: (1) MEQ-5, sleep quality, depression level: Indirect effect value = -0.29, accounting for 38.7% of the total effect; (2) MEQ-5, social function, depression level: Indirect effect value = -0.12, accounting for 16% of the total effect; and (3) MEQ-5, sleep quality, social function, depression level: Indirect effect value = -0.11, accounting for 14.6% of the total effect. All effects were significant as their 95%CIs did not include zero.

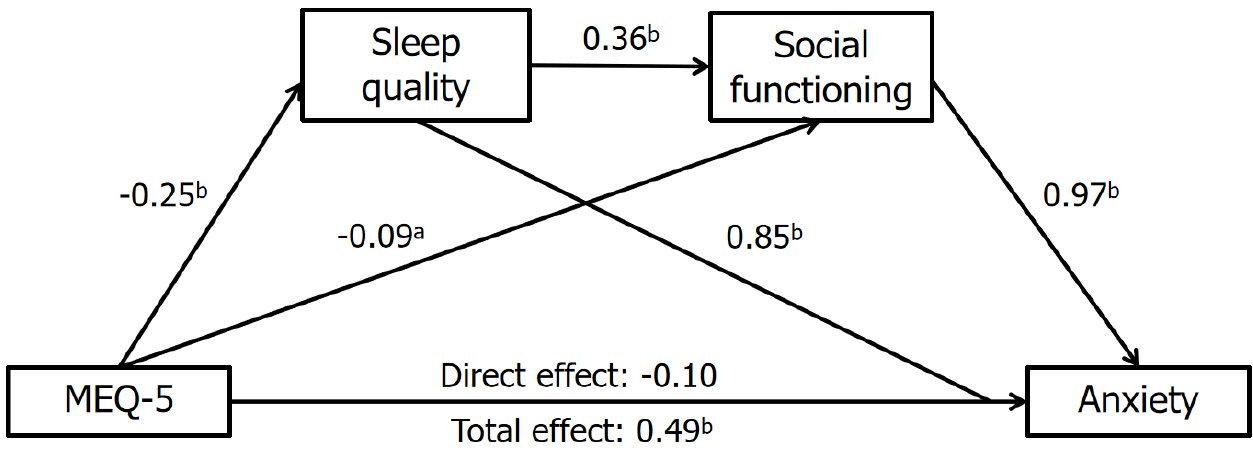

Similarly, using the same covariates, we examined the mediating effects of sleep quality and social function in the relationship between chronotype and anxiety levels. The results showed that the total indirect effect of sleep quality and social function on the relationship between chronotype and anxiety levels was -0.39, accounting for 79.6% of the total effect. The 95%CI did not include zero, indicating significant mediation effects (Figure 2; Table 4). This mediation effect consisted of three pathways: (1) MEQ-5, sleep quality, anxiety level: Indirect effect value = -0.21, accounting for 42.8% of the total effect; (2) MEQ-5, social function, anxiety level: Indirect effect value = -0.09, accounting for 18.4% of the total effect; and (3) MEQ-5, sleep quality, social function, anxiety level: Indirect effect value = -0.09, accounting for 18.4% of the total effect. All indirect effects were statistically significant.

| β | t | P value | 95%CI | |

| MEQ-5, sleep quality | -0.25 | -6.27 | < 0.001 | (-0.33 to -0.17) |

| MEQ-5, social functioning | -0.09 | -2.39 | 0.018 | (-0.17 to -0.02) |

| Sleep quality, social functioning | 0.36 | 7.48 | < 0.001 | (0.26-0.45) |

| MEQ-5, anxiety level | -0.09 | -0.94 | 0.350 | (-0.29 to 0.10) |

| Sleep quality, anxiety level | 0.85 | 6.44 | < 0.001 | (0.59-1.11) |

| Social functioning, anxiety level | 0.97 | 7.31 | < 0.001 | (0.71-1.24) |

Chronotype, a well-established indicator of circadian rhythm disturbances, has been closely linked to mental health outcomes. While prior research has examined chronotype in relation to mental health, few studies have explored the underlying mechanisms explaining this association, particularly in adolescents. This study proposed a multi-mediator model, hypothesizing that the relationship between chronotype and adolescent mental health is indirectly influenced by sleep quality and social function. The findings confirm that chronotype does not exert a direct effect on adolescent mental health but instead influences it through these mediators. This study is also the first to establish a chain mediation model incorporating social function in the relationship between chronotype and adolescent mental health, providing new insights into the complex interplay of biological rhythms, sleep, and social adjustment[19].

Consistent with previous research, the results of Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated that lower MEQ-5 scores (reflecting an evening chronotype) were significantly associated with higher depression and anxiety scores (HAMD and HAMA), poorer sleep quality (PSQI), and impaired social function (SDSS). These findings align with studies indicating that circadian misalignment is a significant contributor to emotional distress[20]. A seven-year longitudinal study previously demonstrated that individuals with an earlier chronotype tend to exhibit milder depressive symptoms, while changes in chronotype are associated with variations in depression severity over time[21]. Our findings further reinforce the notion that evening chronotype is a vulnerability factor for adolescent mental health problems.

Mediation analysis revealed that sleep quality plays a key role in linking chronotype to mental health outcomes. Specifically, sleep quality mediated 38.7% of the relationship between chronotype and depression and 42.8% of the relationship with anxiety, suggesting that adolescents with an evening chronotype are more likely to experience sleep disturbances, which in turn exacerbate psychological distress. The biological preference for late-night activity among evening-type individuals conflicts with external demands such as early school schedules, leading to sleep deprivation and impaired sleep quality[22]. Sleep is essential for emotional regulation, and poor sleep quality has been shown to increase susceptibility to negative emotions such as anxiety and depression[23]. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that adolescents with both an evening chronotype and insomnia are at a significantly higher risk for depression and suicidal ideation than those with either condition alone, highlighting the importance of addressing circadian rhythm disruptions as a mental health intervention strategy[24].

In addition to sleep quality, social function also played a significant mediating role in the relationship between chronotype and mental health, accounting for 16% of the effect on depression and 18.4% on anxiety. Adolescence is a critical period for social and cognitive development, and disruptions in sleep-wake patterns can have profound consequences for social functioning[25]. Evening-type adolescents may experience chronic fatigue due to late bedtimes and insufficient sleep, leading to impaired cognitive efficiency and reduced ability to engage in social and academic activities. This decreased functioning can lower self-efficacy, increase negative self-perceptions, and contribute to difficulties in interpersonal relationships, all of which are known risk factors for depression and anxiety[26].

Moreover, the findings revealed a chain mediation effect, in which sleep quality and social function together explained 69.3% of the total effect of chronotype on depression and 79.3% on anxiety. These results suggest that circadian rhythm disturbances first lead to reduced sleep quality, which subsequently affects social function, increasing negative cognitive patterns and psychological distress[27-31]. This interplay highlights the importance of addressing both sleep quality and social adjustment in interventions for adolescent mental health.

Overall, this study identified three pathways through which chronotype influences adolescent mental health: (1) Independent mediation by sleep quality; (2) Independent mediation by social function; and (3) Chain mediation via sleep quality and social function. These findings provide new perspectives on the mechanisms underlying the link between chronotype and adolescent mental health, emphasizing the necessity of considering both sleep and social function in interventions aimed at improving psychological well-being.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, making it unclear whether chronotype directly influences mental health outcomes or whether bidirectional influences exist. Future longitudinal studies should investigate how changes in chronotype affect mental health over time. Second, the sample size, while sufficient for statistical analysis, remains relatively small, which may introduce sampling bias. Future studies should aim for larger, multi-center samples, particularly in clinical settings, to enhance generalizability. Third, all variables were assessed through self-reported questionnaires, which are susceptible to recall bias and subjective interpretation. The evaluation of circadian rhythms and sleep quality relied on subjective measures rather than objective assessments, such as actigraphy or polysomnography. Incorporating physiological measures in future research would provide a more comprehensive understanding of sleep patterns and their effects on mental health.

Fourth, cultural and socioeconomic factors may have influenced our findings. Chronotype preferences, sleep patterns, and social behaviors can vary substantially across different cultural backgrounds and economic contexts. For instance, adolescents in urban settings may face more academic stress, later school dismissal times, and greater exposure to digital devices compared to their rural counterparts. These contextual factors could impact sleep quality and social functioning, and thus should be considered in future studies to improve the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the measurement of social function was based on the total SDSS score, which may not fully capture the complexity of social functioning. Future studies should employ multidimensional assessments that consider specific aspects of social adaptation, including peer interactions, family relationships, and school engagement.

This study provides novel insights into the relationship between chronotype and adolescent mental health, demon

| 1. | Kieling C, Buchweitz C, Caye A, Silvani J, Ameis SH, Brunoni AR, Cost KT, Courtney DB, Georgiades K, Merikangas KR, Henderson JL, Polanczyk GV, Rohde LA, Salum GA, Szatmari P. Worldwide Prevalence and Disability From Mental Disorders Across Childhood and Adolescence: Evidence From the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:347-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 143.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sampogna G, Toni C, Catapano P, Rocca BD, Di Vincenzo M, Luciano M, Fiorillo A. New trends in personalized treatment of depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2024;37:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Davey CG, McGorry PD. Early intervention for depression in young people: a blind spot in mental health care. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Montaruli A, Castelli L, Mulè A, Scurati R, Esposito F, Galasso L, Roveda E. Biological Rhythm and Chronotype: New Perspectives in Health. Biomolecules. 2021;11:487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kyriacou CP, Hastings MH. Circadian clocks: genes, sleep, and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Adan A, Archer SN, Hidalgo MP, Di Milia L, Natale V, Randler C. Circadian typology: a comprehensive review. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:1153-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 714] [Cited by in RCA: 933] [Article Influence: 66.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Carpenter JS, Crouse JJ, Scott EM, Naismith SL, Wilson C, Scott J, Merikangas KR, Hickie IB. Circadian depression: A mood disorder phenotype. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;126:79-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scott AJ, Webb TL, Martyn-St James M, Rowse G, Weich S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;60:101556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 114.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu J, Ji X, Pitt S, Wang G, Rovit E, Lipman T, Jiang F. Childhood sleep: physical, cognitive, and behavioral consequences and implications. World J Pediatr. 2024;20:122-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Simor P, Zavecz Z, Pálosi V, Török C, Köteles F. The influence of sleep complaints on the association between chronotype and negative emotionality in young adults. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cacioppo JT. Social neuroscience: understanding the pieces fosters understanding the whole and vice versa. Am Psychol. 2002;57:819-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Oliveri LN, Awerbuch AW, Jarskog LF, Penn DL, Pinkham A, Harvey PD. Depression predicts self assessment of social function in both patients with schizophrenia and healthy people. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adan A, Almirall H. Horne & Östberg morningness-eveningness questionnaire: A reduced scale. Pers Individ Differ. 1991;12:241-253. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21041] [Cited by in RCA: 23364] [Article Influence: 354.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6169] [Cited by in RCA: 7018] [Article Influence: 104.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mollayeva T, Thurairajah P, Burton K, Mollayeva S, Shapiro CM, Colantonio A. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:52-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1288] [Cited by in RCA: 1266] [Article Influence: 126.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang D, Wei J, Li X. The mediating effect of social functioning on the relationship between social support and fatigue in middle-aged and young recipients with liver transplant in China. Front Psychol. 2022;13:895259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression‐Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press, 2014: 335-337. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 585] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Koo DL, Yang KI, Kim JH, Kim D, Sunwoo JS, Hwangbo Y, Lee HR, Hong SB. Association between morningness-eveningness, sleep duration, weekend catch-up sleep and depression among Korean high-school students. J Sleep Res. 2021;30:e13063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Druiven SJM, Hovenkamp-Hermelink JHM, Knapen SE, Kamphuis J, Haarman BCM, Penninx BWJH, Antypa N, Meesters Y, Schoevers RA, Riese H. Stability of chronotype over a 7-year follow-up period and its association with severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:466-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chan NY, Zhang J, Tsang CC, Li AM, Chan JWY, Wing YK, Li SX. The associations of insomnia symptoms and chronotype with daytime sleepiness, mood symptoms and suicide risk in adolescents. Sleep Med. 2020;74:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Archer SN, Viola AU, Kyriakopoulou V, von Schantz M, Dijk DJ. Inter-individual differences in habitual sleep timing and entrained phase of endogenous circadian rhythms of BMAL1, PER2 and PER3 mRNA in human leukocytes. Sleep. 2008;31:608-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Walker MP, van der Helm E. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:731-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tamura N, Okamura K. Longitudinal course and outcome of social jetlag in adolescents: A 1-year follow-up study of the adolescent sleep health epidemiological cohorts. J Sleep Res. 2024;33:e14042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:75-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 577] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hinshaw SP, Nguyen PT, O'Grady SM, Rosenthal EA. Annual Research Review: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women: underrepresentation, longitudinal processes, and key directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63:484-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang Q, Lin S, Li Y, Huang S, Liao Z, Chen X, Shao T, Li Y, Cai Y, Qi J, Shen H. Suicidal Ideation Is Associated With Excessive Smartphone Use Among Chinese College Students. Front Public Health. 2021;9:809463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Roenneberg T, Allebrandt KV, Merrow M, Vetter C. Social jetlag and obesity. Curr Biol. 2012;22:939-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 794] [Cited by in RCA: 1008] [Article Influence: 72.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bjorvatn B, Pallesen S. A practical approach to circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:47-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tekieh T, Lockley SW, Robinson PA, McCloskey S, Zobaer MS, Postnova S. Modeling melanopsin-mediated effects of light on circadian phase, melatonin suppression, and subjective sleepiness. J Pineal Res. 2020;69:e12681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wheaton AG, Ferro GA, Croft JB. School Start Times for Middle School and High School Students - United States, 2011-12 School Year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:809-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |