Published online Oct 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.110643

Revised: July 10, 2025

Accepted: August 6, 2025

Published online: October 19, 2025

Processing time: 107 Days and 7.5 Hours

Grief counseling has become relatively established and is widely used among the families of cancer patients, effectively alleviating their psychological pain. However, in China, due to the influence of Confucianism and other traditional cultures, people generally adhere to the belief of “reincarnation to avoid death”, focusing more on themes of life, such as eugenics and longevity, and paying less attention to matters related to death, including death education and grief counseling. Currently, grief counseling in China is still in an exploratory stage, and there is relatively little research on the psychological status of family mem

To investigate the psychological effects of grief counseling on family members of terminal cancer patients.

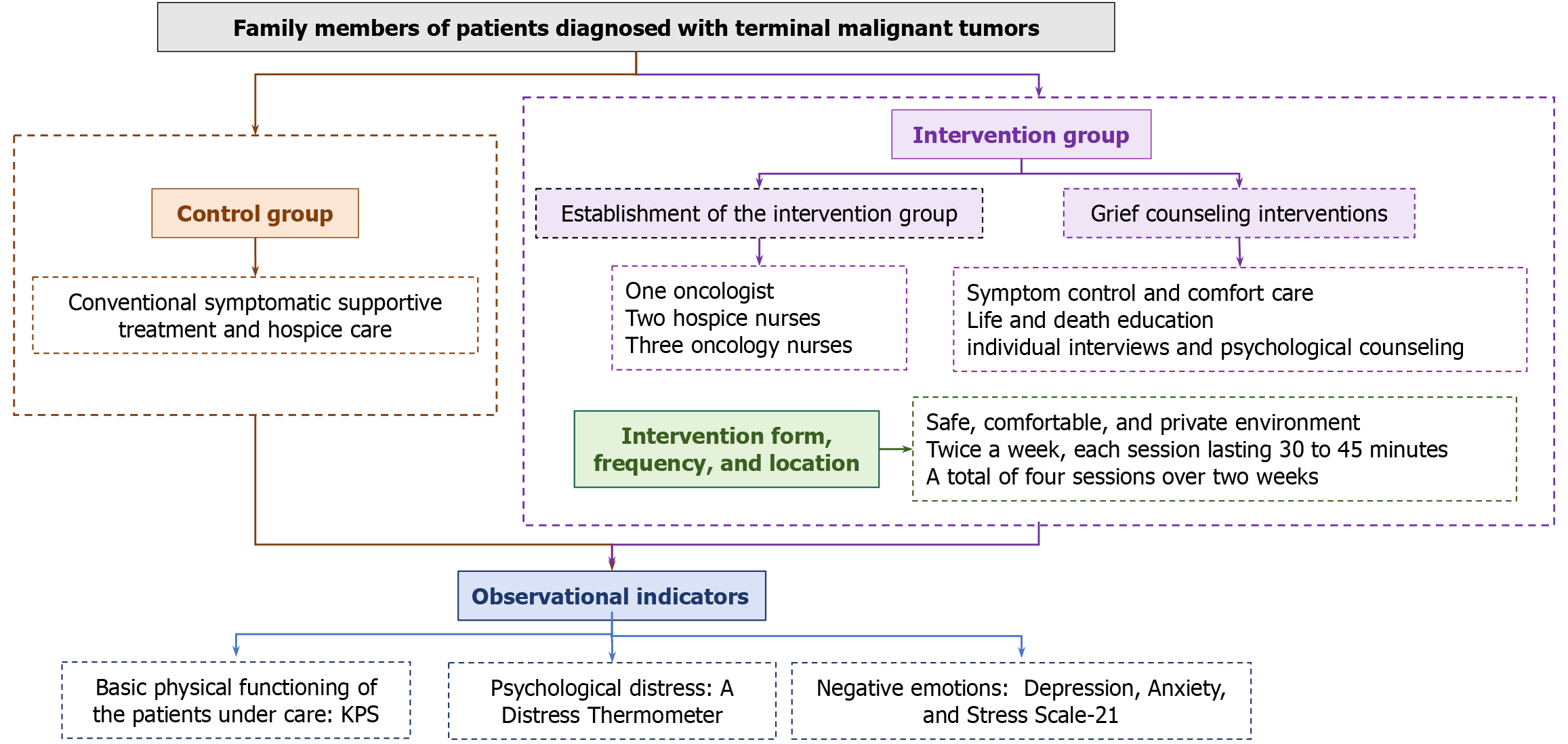

This study was designed as a randomized controlled trial that utilized convenience sampling to select family members of terminal tumor patients who were admitted to the hospice ward of the Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University from January to June 2025 as research subjects. All participants received conventional symptomatic supportive treatment and palliative care. Additionally, the intervention group benefited from extra grief counseling.

The Distress Thermometer (DT) score of the control group slightly decreased compared to before the intervention, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). In contrast, the DT score of the intervention group decreased significantly compared to before the intervention, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). After the intervention, the DT score of the intervention group was lower than that of the control group, and the difference was also statistically significant (P < 0.05). After the intervention, the intervention group performed better DT level than the control group, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05), the intervention group outperformed the control group in terms of depression and anxiety, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Grief counseling can help alleviate the psychological pain and negative emotions experienced by family members of patients with terminal malignant tumors.

Core Tip: This study extensively reviewed relevant literature and clinical practice to provide grief counseling to the families of patients with advanced cancer in China. The aim is to explore the role of grief counseling in alleviating the psychological distress and negative emotions experienced by family members. This study aims to help grieving individuals regain confidence in life and enrich the content of hospice care in China.

- Citation: Lu H, Xu WJ, Chen Y, Zhu LY, Yang YL, Hu YY, Zhang YJ, Cheng Y, Yang YH, Wu RR. Effect of grief counseling on psychological distress and negative emotions among family members of patients with terminal tumors. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(10): 110643

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i10/110643.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.110643

Malignant tumors are one of the leading causes of human mortality, and most of the responsibility for hospice care falls on the patient’s immediate family members[1]. Family members not only need to accompany patients through complex and lengthy oncology treatments but also have to invest significant time and energy in caring for them, all while facing economic pressures and the responsibility of developing treatment plans[2]. Family members of patients with terminal tumors often experience varying degrees of psychological pain and negative emotions, such as avoidance, anxiety, sadness, anger, and fear, both in the immediate period and over the long term before the patient’s death. In serious cases, they may also experience physical symptoms of discomfort, including cognitive impairment, sleep disorders, drug abuse, and immune dysfunction[3,4]. If emotions become unmanageable, there is a risk of self-harm or violent acts toward doctors. Studies have shown that more than 10% of normal grief may evolve into pathological grief, which, if not intervened in a timely manner, can have adverse effects on caregivers and society as a whole[5].

Grief counseling is a key component of hospice care, referring to the use of appropriate psychological support techniques or methods by professionals to help terminally ill patients or bereaved parents process their grief within a reasonable timeframe[6]. This approach can reduce the fear of death and grief experienced by terminally ill patients and enhance the ability of parents who have lost or are about to lose loved ones to cope with adverse life events[7]. In foreign countries, grief counseling has become relatively established and is widely used among the families of cancer patients, effectively alleviating their psychological pain[6,7]. However, in China, due to the influence of Confucianism and other traditional cultures, people generally adhere to the belief of “reincarnation to avoid death”, focusing more on themes of life, such as eugenics and longevity, and paying less attention to matters related to death, including death education and grief counseling[8]. Currently, grief counseling in China is still in an exploratory stage, and there is relatively little research on the psychological status of family members of patients with terminal tumors.

This study extensively consulted relevant literature and clinical practice, conducting grief counseling for the families of terminal cancer patients in China. Its aim was to explore the role of grief counseling in alleviating the psychological pain and negative emotions experienced by family members. This research aimed to assist grieving individuals in regaining their confidence in life and to enrich the content of hospice care in China.

This study was a randomized controlled trial. Using a convenience sampling method, the study subjects were selected from the family members of terminal tumor patients who were admitted to the hospice ward of the Department of Oncology of the Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University from January to June 2025. Participants voluntarily joined the study and provided written informed consent. The Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University approved the study (Approval No. LS2023101), registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (No. ChiCTR2500100727). The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Family members of patients diagnosed with terminal malignant tumors (with an expected lifespan of 3-6 months); (2) Age between 18 and 80 years; (3) The patient’s main companion had been accompanying the patient for at least 3 months in the last six months and had spent at least 5 hours per day with the patient; (4) Clear consciousness and normal cognitive ability; (5) Voluntarily participated in this study and signed an informed consent form; (6) A psychological distress score of ≥ 4 points; and (7) Patient receiving care had a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score of ≥ 60 points.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Individuals with consciousness disorders or mental illnesses who were unable to cooperate with the survey; (2) Those who were unclear about the patient’s condition; and (3) Individuals who had participated in similar research.

The sample size was calculated according to the formula N1 = N2 = 2 × [(Zα + Zβ)σ/δ]2, where α was set at 0.05 and β was at 0.10, conducting a two-sided test[9]. Additionally, a 5% to 10% missing rate was considered, leading to a final determination of 43 cases in both the intervention group and the control group, for a total sample size of 86 cases. The study subjects were randomly selected from a sealed, opaque container containing numbered stickers from 1 to 86. The intervention group consisted of odd-numbered stickers, and the control group consisted of even-numbered stickers, with each group comprising 43 cases. Ultimately, there were 81 valid samples, with 40 valid samples in the control group and 41 valid samples in the intervention group.

Conventional symptomatic supportive treatment and hospice care were implemented for the families of patients with terminal tumors. This included informing them about the condition and prognosis, explaining relevant knowledge to alleviate the cancer pain, providing dietary care, life care, and guidance for psychological stress reduction.

Based on relevant literature and expert advice on grief counseling both domestically and internationally, combined with clinical experience, the following grief counseling plan was constructed as follow. Establishment of the intervention group: The group consisted of one oncologist, two hospice nurses, and three oncology nurses. A grief counseling plan was initially developed by the oncologist and the two hospice nurses. One oncology nurse was responsible for explaining disease-related knowledge and guiding the implementation of the grief counseling program, while the other two oncology nurses were responsible for the implementation of the grief counseling and the management of the follow-up.

Symptom control and comfort care: Family members were promptly informed about the role and appropriate use of pain medication to minimize anxiety caused by the patient’s pain. At the same time, patients and their families were guided to use music therapy and aromatherapy. Soft and soothing music was played one hour before family members went to bed at night, and essential oils such as lavender and geranium were provided for sniffing to help them stay in a comfortable and relaxed state.

Life and death education: The ward held a monthly “brave face” family-theme activity. Hospice nurses shared life and death education courses with family members about the natural laws of life, death, and aging. Simultaneously, psychologists and volunteers were invited to meet face-to-face with family members at the event every month to answer questions and help alleviate their negative emotions.

Individual interviews and psychological counseling: For families of patients experiencing extremely high psychological pressure, special one-on-one communication sessions were held in a quiet conference room. By carefully listening and observing, the team sought to understand the attitudes of family members toward patients who were about to finish their lives, helping them establish a correct understanding of disease and death. During interactions, body language was employed as much as possible, including handshakes and hugs, to provide comfort, help release negative emotions of repression and grief, and encourage them to bravely face the reality of impending loss.

A safe, comfortable, and private environment was chosen, such as a psychological counseling room or a conference room in the ward, for team members to have face-to-face communication with the subjects. The intervention was conducted twice a week, with each session lasting approximately 30 to 45 minutes, for a total of four sessions over two weeks. When choosing specific times, efforts were made to avoid peak periods of concentrated treatment for patients’ families, while respecting their genuine wishes and ensuring that normal treatment and care were not disrupted.

General information questionnaire: The general information questionnaire was designed by researchers and mainly included the following information: Age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education level, religious beliefs, occupational status, initial tumor type, staging, and whether the patient being cared for had metastasis.

Basic physical functioning of the patients under care: The KPS was used to evaluate the physical activity and self-care abilities of patients with malignant tumors under nursing care, with a score range of 0 to 100. The higher the score, the better the basic physical function status[10].

Psychological distress: A Distress Thermometer (DT) was used to evaluate the psychological distress of the subjects[11]. DT was a single-entry screening tool used to measure the degree of psychological distress, utilizing a 0 to 10 numerical scale, with 0 indicating no distress, 1 to 3 indicating mild distress, 4 to 6 indicating moderate distress, 7 to 9 indicating severe distress, and 10 indicating extreme distress. Patients and their families were required to score themselves based on their level of psychological distress in the past week, with DT ≥ 4 having clinical significance.

Negative emotions: The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) was used to assess the level of psychological distress in participants. This scale consisted of 3 subscales with a total of 21 entries, representing depression (7 entries), anxiety (7 entries), and stress (7 entries)[12]. Validated by Chinese scholars, the Cronbach’s a coefficient among Chinese adults of the DASS-21 scale for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales and the total scale were 0.823, 0.754, 0.796, and 0.912, respectively[13]. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale, where “0, 1, 2, and 3” represented “not matching, fairly matching, very matching, and most matching” respectively. Higher scores reflecting worse negative emotions status. The research flowchart is illustrated in Figure 1.

Data collection and quality control: Eligible subjects were selected, and their informed consent was obtained. On the first day of patient admission, a general information questionnaire, KPS, DT, and DASS-21 were distributed for a baseline survey. The questionnaire was completed by the subjects themselves; if the subjects were unable to fill out the questionnaire independently, the researchers read each item and filled it out in accordance with the subjects’ responses. After completing the questionnaire, it was recovered and checked on the spot. If any omissions or errors were found, the researchers promptly requested participants to make corrections to ensure the accuracy of the questionnaire. At the end of the last intervention, telephone or WeChat follow-up were conducted, and the subjects were re-evaluated using DT and DASS-21.

During the study period, unified training was provided to data collectors, and intervention measures were implemented to ensure that all processes were conducted in a standardized manner. Subjects were strictly selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure their eligibility for the study. At the same time, the subjects were randomly assigned to groups, and the intervention measures were strictly implemented according to the intervention mode, maintaining relative independence between the intervention group and the control group to ensure that the intervention content would not be confounded with one another during the project implementation process.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 17.0 software. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyze participants’ demographic characteristics. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed variables or median and interquartile range for non-normal distributions, as determined by normality tests. All categorical variables are reported as frequencies (percentages). Between-group comparisons of baseline characteristics were performed using t-tests, χ2 tests, or Mann-Whitney U tests. Within-group differences in outcome measures before and after the intervention were assessed using paired-sample t-tests. Between-group differences in outcome measures were analyzed using independent-sample t-tests. All tests were executed using a two-sided test, with a significance level set at α = 0.05. P < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

This study was conducted with the approval of the hospital ethics committee and the consent of the intervention subjects. Before the start of the study, researchers fully explained the purpose, significance, and procedures of the study to the subjects and obtained their informed consent. The data of the subjects were encoded and processed solely for the purposes of this study, and were kept strictly confidential and not leaked. During the implementation process, the principle of voluntariness was followed, and participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any stage. After the intervention was completed, if it was proven effective, the plan would be replicated in the control group following the principle of fairness.

This study included a total of 86 cases of family members of patients with terminal malignant tumors, with 43 cases in each group. During the research process, a total of 5 cases withdrew halfway, including 2 cases in the control group who withdrew due to critical condition and 1 case who withdrew due to loss to follow-up. One case in the intervention group withdrew due to transfer, and 1 case withdrew due to unwillingness to continue participating. In the end, there were 40 effective cases in the control group and 41 effective cases in the intervention group. A total of 81 family members of patients successfully completed the study.

Comparison of general socio-demographic data of subjects in the two groups: Demographic data of family members were compared between the two groups of patients, including gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, average monthly family income, and occupational status. The research results indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in the socio-demographic data between the two groups of subjects (P > 0.05), which demonstrated the comparability of the data between the two groups (Table 1).

| Items | Control group (n = 40) | Intervention group (n = 41) | χ2/t | P value |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 14 (35.0) | 6 (39.0) | 0.141 | 0.708 |

| Female | 26 (65.0) | 25 (61.0) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 49.93 ± 11.14 | 49.17 ± 10.53 | 0.313 | 0.755 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Unmarried | 4 (10.0) | 3 (7.3) | 0.748 | 0.862 |

| Married | 30 (75.0) | 29 (70.7) | ||

| Divorced | 4 (10.0) | 6 (14.7) | ||

| Widowed | 2 (5.0) | 3 (7.3) | ||

| Education level | ||||

| Junior high school and below | 15 (37.5) | 15 (36.6) | 1.226 | 0.874 |

| High school and university | 22 (55.0) | 22 (53.7) | ||

| Postgraduate | 3 (7.5) | 4 (9.7) | ||

| Religious belief | ||||

| Yes | 4 (10.0) | 7 (17.1) | 0.863 | 0.353 |

| No | 36 (90.0) | 34 (82.9) | ||

| Monthly per capita household income (yuan) | ||||

| < 1000 | 11 (27.5) | 15 (36.6) | 0.770 | 0.681 |

| 1000-3000 | 21 (52.5) | 19 (46.3) | ||

| > 3000 | 8 (20.0) | 7 (17.1) | ||

| Relationship with patients | ||||

| Parents | 9 (22.5) | 7 (17.1) | 1.053 | 0.902 |

| Spouses | 11 (27.5) | 9 (22.0) | ||

| Children | 15 (37.5) | 18 (43.8) | ||

| Other | 5 (12.5) | 7 (17.1) | ||

| Occupational status | ||||

| Employed | 14 (35.0) | 12 (29.3) | 0.305 | 0.581 |

| Workless | 26 (65.0) | 29 (70.7) |

Comparison of clinical disease information of patients cared for by subjects in the two groups: In comparing the clinical disease information of patients cared for by the two groups of subjects, such as tumor category, disease staging, whether metastasis, and KPS score, the results showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05), suggesting that the clinical disease data between the two groups of subjects were comparable (Table 2).

| Items | Control group (n = 40) | Intervention group (n = 41) | χ2/t | P value |

| Cancer category | ||||

| Lung cancer | 11 (27.5) | 10 (24.4) | 0.783 | 0.941 |

| Breast cancer | 9 (22.5) | 12 (29.3) | ||

| Digestive tract cancer | 10 (25.0) | 9 (21.9) | ||

| Gynecologic cancer | 7 (17.5) | 8 (19.5) | ||

| Other | 3 (7.5) | 2 (4.9) | ||

| Cancer stages | ||||

| Stage I | 6 (15.0) | 7 (17.1) | 0.307 | 0.857 |

| Stage II | 21 (52.5) | 19 (46.3) | ||

| Stage III | 13 (32.5) | 15 (36.6) | ||

| Transfer or not | ||||

| Yes | 13 (32.5) | 15 (36.6) | 0.149 | 0.699 |

| No | 27 (67.5) | 26 (63.4) | ||

| KPS score | ||||

| 60-70 | 4 (10.0) | 6 (14.6) | 1.303 | 0.728 |

| 70-80 | 17 (42.5) | 15 (36.6) | ||

| 80-90 | 14 (35.0) | 17 (41.5) | ||

| 90-100 | 5 (12.5) | 3 (7.3) |

Comparison of DT degree grading before the intervention between the two groups of subjects: Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in the DT degree grading between the two groups of subjects (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the DT degree grading of the intervention group was significantly better than that of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Tables 3 and 4).

| Grade | Control group (n = 40) | Intervention group (n = 41) | Z | P value |

| Moderate | 24 (60.0) | 21 (51.2) | -0.790 | 0.429 |

| Severe | 13 (32.5) | 16 (39.0) | ||

| Extremely severe | 3 (7.5) | 4 (9.8) |

| Grade | Control group (n = 40) | Intervention group (n = 41) | Z | P value |

| Mild | 3 (7.5) | 9 (22.0) | -2.492 | 0.013 |

| Moderate | 17 (42.5) | 22 (53.6) | ||

| Severe | 18 (45.0) | 8 (19.5) | ||

| Extremely severe | 2 (5.0) | 2 (4.9) |

Comparison of DT scores between the two groups before and after intervention: Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in DT scores between the two groups of subjects (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the DT scores of the intervention group were found to be significantly lower than those of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). After the intervention, the DT score of the intervention group was significantly lower than it had been before the intervention, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). The DT score of the control group was slightly lower than it had been before the intervention, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Table 5).

| Control group (n = 40) | Intervention group (n = 41) | t | P value | |

| Pre-DT | 6.15 ± 1.82 | 6.27 ± 1.88 | -0.287 | 0.775 |

| Post-DT | 6.08 ± 1.86 | 5.05 ± 1.95 | 2.424 | 0.018 |

| t | 0.270 | 6.782 | ||

| P value | 0.789 | < 0.001 |

The research results showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the DASS-21 dimension scores between the two groups of subjects before the intervention (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the intervention group scored significantly higher than the control group in the dimensions of depression, anxiety, and stress (P < 0.05). The DASS-21 dimension score of the intervention group was significantly lower than it had been before the intervention (P < 0.05), while the DASS-21 dimension score of the control group was slightly lower than it had been before the intervention; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Table 6).

| Pre-DASS-21 | Post-DASS-21 | t | P value | ||

| Depression | Control group (n = 40) | 13.02 ± 1.76 | 10.10 ± 1.83 | -0.516 | 0.609 |

| Intervention group (n =41) | 12.98 ± 1.71 | 8.05 ± 1.73 | -4.351 | < 0.001 | |

| t | -0.125 | -5.300 | |||

| P value | 0.901 | < 0.001 | |||

| Anxiety | Control group (n = 40) | 14.07 ± 1.75 | 9.05 ± 2.39 | -0.429 | 0.670 |

| Intervention group (n = 41) | 14.05 ± 1.70 | 7.02 ± 1.85 | -3.602 | 0.034 | |

| t | -0.067 | -4.379 | |||

| P value | 0.947 | < 0.001 | |||

| Stress | Control group (n = 40) | 17.14 ± 1.56 | 14.02 ± 1.89 | -0.781 | 0.618 |

| Intervention group (n = 41) | 17.05 ± 1.63 | 12.40 ± 2.20 | -2.503 | 0.028 | |

| t | -0.279 | -3.659 | |||

| P value | 0.781 | < 0.001 |

Currently, grief counseling is the core task of oncology hospice care in China[14]. Although the scope of hospice interventions has expanded to include patients’ families, there is still limited research on grief counseling interventions for families of terminal cancer patients. Therefore, the timing and intervention measures for grief counseling urgently need to be further explored and enriched.

The results of this study indicated that prior to the intervention, both groups of subjects had high levels of DT scores and degree ratings. This may have been due to the subjects in this study were caring for patients with terminal tumors who were nearing the end of their lives. The results of the intervention showed that grief counseling could reduce the psychological distress levels of family members of terminal cancer patients and improve psychological problems related to worry, sadness, and sleep. This research findings were consistent with similar studies both domestically and internationally. For example, research indicates that grief counseling significantly alleviates psychological pain in parents who have lost a child in an accident and relatives of those with chronic illnesses, with effects becoming even more pronounced over time[15,16].

Overwhelming traumatic events can shatter an individual’s fundamental assumptions about the world, including their understanding of self-identity, interpersonal relationships, and meaningful social engagement. This disruption of one’s assumptive world often leads to profound disorientation and distress. From the cognitive-constructivist perspective by Neimeyer[17], meaning reconstruction plays a pivotal role in trauma adaptation. The formation of new meaning structures involves: (1) Attentional reorientation: Facilitating emotional regulation through cognitive reframing; (2) Cognitive reappraisal: Modifying situational meaning to alter emotional responses; and (3) Response modulation: Influencing physiological, experiential, and behavioral outcomes. This theory elucidates the pivotal role of meaning-making in grief counseling, demonstrating how successful meaning reconstruction facilitates psychological adjustment through these interconnected cognitive-emotional processes[18].

There may have been several reasons why grief counseling could reduce the psychological pain of family members of patients with terminal tumors: (1) In the current social context of China, limited medical resources tend to be allocated to the emergency treatment of tumors, with less attention being paid to the psychological status of patients and their families[19]. Consequently, psychological problems are often overlooked[20]. The long-term accumulation of negative emotions may exacerbate these issues. Grief counseling provides one-on-one communication opportunities for patients’ families, ensuring their privacy and encouraging them to open up and express their feelings freely, which helps them release negative emotions; and (2) Grief counseling gradually leads to the externalization of problems, helping patients’ families explore the sources, developmental processes, and impacts of their psychological pain on their lives. Through this approach, family members could separate their pain from themselves, view these issues and their consequences from a new perspective, and increase their psychological space for self-examination[21].

The research results indicated that the negative emotions of the intervention group participants changed towards positive directions, which was consistent with the research findings of other scholars[22,23]. When facing negative events and psychological pain, family members of cancer patients may experience different negative emotions due to differences in personal growth environment, cultural level, economic status, and social support system[24,25]. Negative emotions play a mediating role in the psychosomatic responses of family members of cancer patients, and the relationship with psychosomatic health is so complex. Therefore, in different diseases and treatment processes, the negative emotions of patients’ families cannot be consistent, and there are individual differences in the intervention process[26-28]. Although it is not hard to completely prevent patients’ family members from using different coping strategies and psychological defense mechanisms, in the intervention of grief counseling, it is possible to analyze the specific situation of patients’ family members based on the actual situation, fully guide and tap their own potential, and gradually help them choose appropriate coping strategies.

Recent studies have revealed that anxiety is associated with neuronal activity in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex[29]. Direct stimulation of amygdala neurons in mice induces anxiety- and fear-like behaviors, mirroring responses observed following repeated electric shocks. Positron emission tomography scans of the human brain demonstrate significantly enhanced signals in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex during anxious states[30]. Notably, olfactory and auditory pathways project not only to their respective sensory cortices but also to the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, suggesting that aromatherapy and music interventions may modulate amygdal-prefrontal cortex excitability, thereby attenuating anxiety[31]. Soothing music and faint smell of aromatic essential oil can distract people’s attention, relieve pain caused by cancer, and enable patients and their families to relax effectively. In the process of aromatherapy and music therapy, family members can temporarily forget the painful reality, allowing their body and mind to have a brief rest, and their inner sadness can also be effectively relieved[32].

Comparative studies reveal distinct cultural differences in bereavement care approaches. International research demonstrates more open discourse on bereavement, with systematically developed pre- and post-bereavement in

There were still some deficiencies in the implementation of this study: (1) The number of included cases was relatively low, and the interventions did not fully account for the grief reactions exhibited by families of terminal cancer patients of different genders. The interventions for family members with different spiritual needs were not comprehensive enough; (2) The absence of assessor blinding in outcome evaluation represents a potential source of detection bias. While our raters were trained to follow standardized protocols, unblinded assessments may have influenced scoring interpretations. Rigorous blinding procedures have been implemented in all current evaluations; and (3) The brief intervention period (2 weeks) and lack of long-term follow-up restrict our ability to evaluate the durability of observed effects. Future studies with extended follow-ups (e.g., 3-6 months) are warranted to assess whether symptom improvements persist beyond the immediate post-intervention phase. The follow-up period of this study was relatively short, highlighting the need to adopt different counseling methods to meet the varying needs of different populations. Targeting the grief reactions of different groups and employing corresponding counseling methods could serve as a new direction for future research. It was recommended to adopt a multi-modality, personalized, and long-term effective approach to grief counseling and to evaluate its effectiveness across various aspects. Future studies should expand the sample size, extend the intervention time as appropriate, and conduct follow-up with patient families through various channels to verify the long-term effects of grief counseling.

Grief counseling could reduce the psychological pain and negative emotions of family members of patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignant tumors, and it had significant positive implications. Through grief counseling, the negative emotions of the patients’ family members were able to shift toward a more positive direction. Providing early grief counseling to the families of terminally ill patients not only improved their quality of life and reduced their pain but also reduced the pressure that family members bore in various aspects.

| 1. | Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Taylor RA, Wells RD, Hendricks BA, Bechthold AC, Reed RD, Harrell ER, Dosse CK, Engler S, McKie P, Ejem D, Bakitas MA, Rosenberg AR. Resilience, preparedness, and distress among family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:6913-6920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1227-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ishida K, Sato K, Komatsu H, Morita T, Akechi T, Uchida M, Masukawa K, Igarashi N, Kizawa Y, Tsuneto S, Shima Y, Miyashita M, Ando S. Nationwide survey on family caregiver-perceived experiences of patients with cancer of unknown primary site. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:6353-6363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Asmat A, Malik AN, Prigerson HG, Saleem T. Beyond bereavement: Identifying risk and protective factors for prolonged grief disorder. Death Stud. 2025;49:907-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Szuhany KL, Malgaroli M, Miron CD, Simon NM. Prolonged Grief Disorder: Course, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021;19:161-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Waller A, Turon H, Mansfield E, Clark K, Hobden B, Sanson-Fisher R. Assisting the bereaved: A systematic review of the evidence for grief counselling. Palliat Med. 2016;30:132-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Daniel T. Adding a New Dimension to Grief Counseling: Creative Personal Ritual as a Therapeutic Tool for Loss, Trauma and Transition. Omega (Westport). 2023;87:363-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shu W, Miao Q, Feng J, Liang G, Zhang J, Zhang J. Exploring the needs and barriers for death education in China: Getting answers from heart transplant recipients' inner experience of death. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1082979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Luo JE. [Design and effect evaluation of a grief counseling training course for nurses based on the Fink model]. Southwest Medical University, 2019. |

| 10. | Friendlander AH, Ettinger RL. Karnofsky performance status scale. Spec Care Dentist. 2009;29:147-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ownby KK. Use of the Distress Thermometer in Clinical Practice. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2019;10:175-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6494] [Cited by in RCA: 7938] [Article Influence: 256.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wen Y, Wu DY, Lv XJ, Li HG, Liu XC, Yang YP, Xu YX, Zhao Y. [Psychometric properties of the Chinese Short Version of Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale in Chinese adults]. Zhongguo Gonggong Weisheng. 2012;28:1436-1438. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Xu Y, Liu Y, Kang Y, Wang D, Zhou Y, Wu L, Yuan L. Experiences of family caregivers of patients with end-of-life cancer during the transition from hospital to home palliative care: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23:230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yuan MD, Wang ZQ, Fei L, Zhong BL. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder and its symptoms in Chinese parents who lost their only child: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1016160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Duran S, Altun A. Prolonged grief, reconstruction of meaning, and posttraumatic growth in nursing home residents who have lost loved ones. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2024;24:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Neimeyer RA. Reconstructing meaning in bereavement. Riv Psichiatr. 2011;46:332-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Neimeyer RA. Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Stud. 2019;43:79-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alacacioglu A, Tarhan O, Alacacioglu I, Dirican A, Yilmaz U. Depression and anxiety in cancer patients and their relatives. J BUON. 2013;18:767-774. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Stevens JM, Montgomery K, Miller M, Saeidzadeh S, Kwekkeboom KL. Common patient-reported sources of cancer-related distress in adults with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e7450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fernandez R. Why Prospective Bereavement Counseling Is Crucial for Peace-Finding After Loss. AMA J Ethics. 2024;26:E881-E885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zaider TI, Kissane DW, Schofield E, Li Y, Masterson M. Cancer-related communication during sessions of family therapy at the end of life. Psychooncology. 2020;29:373-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kissane DW, McKenzie M, Bloch S, Moskowitz C, McKenzie DP, O'Neill I. Family focused grief therapy: a randomized, controlled trial in palliative care and bereavement. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1208-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Stone M, McDonald FEJ, Kangas M, Sherman K, Allison KR. Bereavement guilt among young adults impacted by caregivers' cancer: Associations with attachment style, experiential avoidance, and psychological flexibility. Palliat Support Care. 2024;1-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Gupta N, Zebib L, Wittmann D, Nelson CJ, Salter CA, Mulhall JP, Byrne N, Nolasco TS, Loeb S. Understanding the sexual health perceptions, concerns, and needs of female partners of prostate cancer survivors. J Sex Med. 2023;20:651-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Clark DA, Beck AT. Cognitive theory and therapy of anxiety and depression: convergence with neurobiological findings. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:418-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kashif A, Malik JA, Akhter T. The mediating role of metaworry between emotion oriented coping and negative beliefs about rumination: A transversal analysis of emotional dysregulation. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69:794-798. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Ziadni MS, You DS, Johnson L, Lumley MA, Darnall BD. Emotions matter: The role of emotional approach coping in chronic pain. Eur J Pain. 2020;24:1775-1784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tovote P, Esposito MS, Botta P, Chaudun F, Fadok JP, Markovic M, Wolff SB, Ramakrishnan C, Fenno L, Deisseroth K, Herry C, Arber S, Lüthi A. Midbrain circuits for defensive behaviour. Nature. 2016;534:206-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 51.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 30. | Fredrikson M, Faria V. Neuroimaging in anxiety disorders. Mod Trends Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;29:47-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hong W, Luo L. Genetic control of wiring specificity in the fly olfactory system. Genetics. 2014;196:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Deng C, Xie Y, Liu Y, Li Y, Xiao Y. Aromatherapy Plus Music Therapy Improve Pain Intensity and Anxiety Scores in Patients With Breast Cancer During Perioperative Periods: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Breast Cancer. 2022;22:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Reininghaus U, Reinhold AS, Priebe S, Rauschenberg C, Fleck L, Schick A, Schirmbeck F, Myin-Germeys I, Morgan C, Hartmann JA. Toward Equitable Interventions in Public Mental Health: A Review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:1270-1275. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |