Published online Jan 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i1.100308

Revised: October 24, 2024

Accepted: November 18, 2024

Published online: January 19, 2025

Processing time: 127 Days and 1 Hours

Antidepressants are the main drugs used to treat depression, but they have not been shown to be effective in the treatment of child and adolescent depression. However, many adolescent depression treatment guidelines still recommend the use of antidepressants, especially specific serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Previous studies have suggested that antidepressants have little therapeutic effect but many side effects, such as switching to mania, suicide, and non-suicidal self injury (NSSI), in the treatment of child and adolescent depression. In the process of developing guidelines, drug recommendations should not only focus on impro

Core Tip: Antidepressants are not effective in the treatment of child and adolescent depression, and by contrast, it can induce serious side effects of switching to mania and suicide including non-suicidal self injury. However, many children and adolescent depression treatment guidelines still recommend the use of antidepressants. Drug recommendations should not only focus on improving symptoms, but they should also consider potential side effects.

- Citation: Xu M, Jin HY, Sun FL, Jin WD. Negative efficacy of antidepressants in pharmacotherapy of child and adolescent depression. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(1): 100308

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i1/100308.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i1.100308

Adolescent depression refers to a type of mental illness that occurs during adolescence and is characterized by significant and persistent low mood and lack of interest. The clinical manifestations of adolescent depression are similar to those of adult depression, but they also have their own characteristics, often with irritability and emotional reactions as the core symptoms. They may also manifest as various physical symptoms such as sleep disorders, eating disorders, fatigue, pain, as well as behavioral problems such as self harm, truancy, smoking, alcohol abuse, internet addiction, not doing homework, declining grades, and tense interpersonal relationships[1]. The incidence rate of adolescent depression is 19.85% in China, with 17.8%, 23.7%, and 22.7% in the eastern, central, and western regions, respectively[2]. Adolescents refer to those at 14-18 years old or 10-21 years old[1,3].

A systematical analysis of the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study shows that depression is one of the 10 key diseases leading to an increase in the global burden of disease, and adolescent depression has risen from the 8th place in 1990 to the 4th place in the adolescent burden of disease[3]. Adolescent depression treatment guidelines have been successively released. This section of the guidelines aims to assist clinicians in identifying and initially managing adolescent depression patients in an era of high clinical demand and a shortage of mental health experts[4,5]. All guidelines emphasize the importance of psychological quality. The use of medications is only appropriate when psychological therapy is not effective[1,4,5]. During the application of drugs, the following aspects should be done excellently[5]: (1) Active monitoring of adolescents with mild depression; (2) Application of evidence-based drug therapy and psychotherapy methods in adolescents with moderate and/or severe depression; (3) Closely monitoring side effects from drug or psychotherapy; (4) Consultation and collaboration with mental health experts to care; (5) Specific steps taken when there is partial or no improvement after the initial treatment begins; and (6) Summarizing the strength of every suggestion and the level of its base of evidence. Obviously, choosing which type of medication is a particularly important decision, which requires evidence from evidence-based medicine.

The use of antidepressant drugs for the treatment of depressive disorders is beyond doubt. However, adolescent depression is different from adult depression not only in clinical manifestation, but also in patient response to antidepressant drugs[1,6,7]. This response includes both positive therapeutic effects and negative side effects.

The side effects of antidepressants conclude suicide, switching to mania, serotonin syndrome, sex dysfunction, sleep disorder, and other side effects in every system of the body[8]. Although these side effects are classified into early and late stages, suicide and relapse are still considered the most serious problems[6-8]. These two serious side effects are considered to associated with antidepressant-induced activation[6,7].

Some evidence suggests that exposure to antidepressants appears to increase the risk of suicide in children and young people[9]. Moreover, the use of antidepressants may increase the risk of non-suicidal self injury (NSSI). Among individuals primarily diagnosed with emotional disorders, NSSI significantly decreased during drug-free treatment compared to all other four drug treatment conditions [high-potency antipsychotics P = 0.0009, low-potency antipsychotics P < 10-4, benzodiazepines P < 10-8, and antidepressants/serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) P = 0.0004]. Compared with treatment with benzodiazepines (P = 0.005) and antidepressants/SSRIs (P = 0.01), NSSI was significantly reduced during non-pharmacological treatment in patients with a primary diagnosis of nonaffective disorders[10]. Suicide is common among young people undergoing treatment with SSRI. The attempted suicide proportion remained stable in the early weeks after use of SSRIs. Female gender, previous suicide, depression, and previous NSSI are important predictors of suicide during treatment with SSRIs in young adults[11].

Some evidence has also found that exposure to antidepressants seems to increase the risk of switching to mania in children and young people[12]. Previous antidepressant treatment was associated with an increased incidence of manic/bipolar disorder ranging from 13.1 to 19.1/1000 person years. Multivariate analysis showed a significant correlation with use of SSRIs [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.34, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.18-1.52] and venlafaxine (HR = 1.35, 95%CI: 1.07-1.70)[13]. The younger the age, the more likely it is to turn into mania. Patient age is a contributing factor to the risk of antidepressant associated manic transition. Antidepressant treatment is associated with the highest conversion risk in children aged 10 to 14 years old[14]. The high probability of manic transition may be related to more manic connotations, including mania or hypomania, mixed episode, accelerating of rapid cycling, and antidepressant-induced chronic irritable dysphoria[15].

It is obvious that questioning the use of antidepressants for adolescent depression is also reasonable.

Another question is that antidepressants are ineffective in treating depression in adolescents[16]. In a network meta-analysis, 26 studies were included in a study of child and adolescent depression treated with new generation antidepressants. There is no data available for the two main outcomes (depression and suicide determined through clinical diagnostic interviews), and the results only include secondary outcomes. And most antidepressants may be related to a "small but insignificant" decrease in depressive symptoms on the CDRS-R scale[16]. And it also was found that venlafaxine probably results in an increased odds of suicide-related outcomes. These research results indicate that compared to placebo, most new antidepressants may alleviate depressive symptoms in a small but insignificant way. In addition, most antidepressants may have small but insignificant differences in reducing depressive symptoms.

The latest guidelines for prevention and treatment of adolescent depression were published in 2023. In the guidelines, it was suggested that moderate to severe adolescent depression can be treated with antidepressants, with fluoxetine and sertraline being the first choices[1]. It comes from the meta-analysis of fluoxetine in treating children and adolescents depression[17]. It also comes from “Clinical practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with major and persistent depressive disorders” in 2023[18]. In the latest guidelines, it is recommended that if an antidepressant is ineffective, another antidepressant can be used, which involves almost all SSRIs[1,18]. From this perspective, antidepressants including SSRIs are still the preferred treatment options. Not only that, many guidelines cited by the Chinese guidelines suggest that if medication is needed, antidepressants are first-line choices[1].

Guidelines are an important basis for clinical treatment decisions. In the development of guidelines, drug selection should not only focus on improving symptoms, but it shoul also consider potential side effects. When considering the risk-benefit ratio of antidepressants in management of depressive disorder, these drugs seem to have no significant advantages for children and adolescents[19]. For adults, psychological interventions, clomipramine, SSRIs, or their combinations are effective, but for child and adolescents depression, psychological interventions seems more likely to be effective, whether as monotherapy or in combination with SSRIs[20]. This indicates that effective antidepressant drugs for adult depression may not be effective in adolescent depression, and may even have significant negative effects.

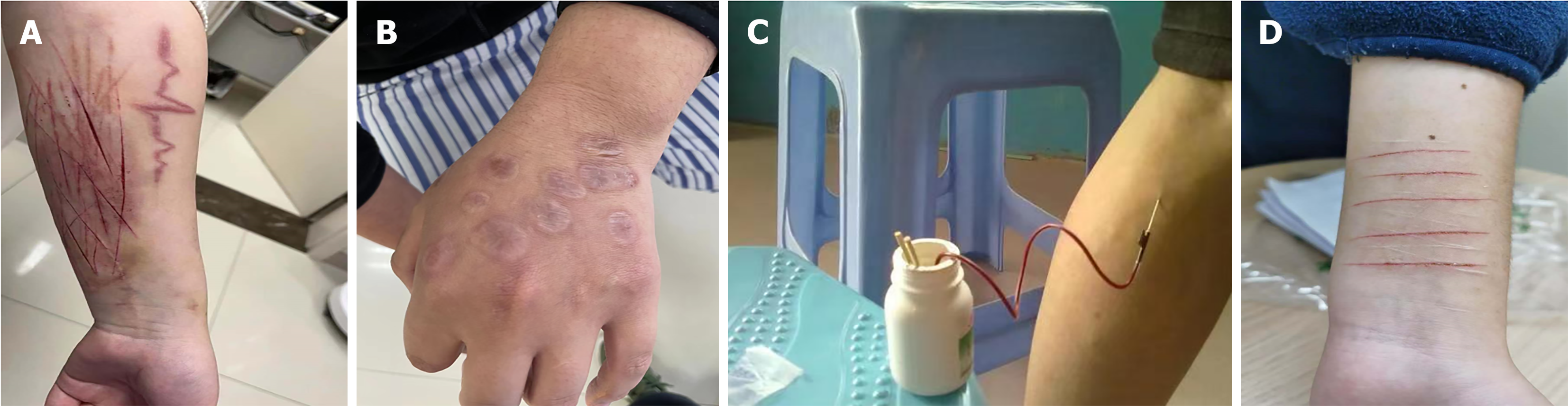

The clinical manifestations of adolescent depression are different from those of adult depression, and the response to antidepressant drugs in adolescents is also different from that in adult depression. This may be related to the heterogeneity of adolescent depression, or it may be related to certain biological factors. Some mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotics may be effective in the treatment of adolescent depression, such as lithium carbonate, lamotrigine, valproate, or lurasidone. In clinical practice, we have encountered many cases of occurrence or aggravation of self injurious behavior caused by the use of antidepressants. Some particularly typical examples are illustrated in Figure 1. These typical cases all exhibit NSSI during therapy with antidepressants. However, our observation results reflect the effectiveness of antidepressants in clinical fact, and suggest that child and adolescent depression have a higher heterogeneous feature, some people may have a greater response, especially in youth. Therefore, guideline makers and others who make recommendations may consider whether it is necessary to recommend the use of next-generation antidepressants for certain individuals in certain situations, especially in youth[16]. Future randomized controlled trials should improve their design, particularly with regards to psychotherapy or combined interventions[20].

We thank Professor Zhou Yong and Lin Yong (Jiaxing University) for sharing ideas and Mr. Zhi-Qiang Miao (Beijing University) for help in literature retrieval and review. We thank Professor Yong-Chun Ma (Zhejiang Province Mental Health Center) for the revision of the manuscript.

| 1. | Yan M, Chen L, Yang M, Zhang L, Niu M, Wu F, Chen Y, Song Z, Zhang Y, Li J, Tian J. Evidence mapping of clinical practice guidelines recommendations and quality for depression in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32:2091-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rao WW, Xu DD, Cao XL, Wen SY, Che WI, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, He F, Xiang YT. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents in China: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:790-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, Stein REK, Laraque D; GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): Part I. Practice Preparation, Identification, Assessment, and Initial Management. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20174081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13226] [Cited by in RCA: 12033] [Article Influence: 2005.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (41)] |

| 5. | Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Laraque D, Stein REK; GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): Part II. Treatment and Ongoing Management. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20174082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Luft MJ, Lamy M, DelBello MP, McNamara RK, Strawn JR. Antidepressant-Induced Activation in Children and Adolescents: Risk, Recognition and Management. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2018;48:50-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Strawn JR, Mills JA, Poweleit EA, Ramsey LB, Croarkin PE. Adverse Effects of Antidepressant Medications and their Management in Children and Adolescents. Pharmacotherapy. 2023;43:675-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhu JF, Jin WD. [Adverse reactions of antidepressant drugs]. Yixue Xinzhi Zazhi. 2018;37:1198-1202. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Li K, Zhou G, Xiao Y, Gu J, Chen Q, Xie S, Wu J. Risk of Suicidal Behaviors and Antidepressant Exposure Among Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:880496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eggart V, Mortazavi M, Kirchner SK, Keeser D, Brandstetter L, Hasan A, Wagner E. Association of Four Medication Classes and Non-suicidal Self-injury in Adolescents with Affective Disorders - A Retrospective Chart Review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2024;57:4-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sørensen JØ, Rasmussen A, Roesbjerg T, Verhulst FC, Pagsberg AK. Suicidality and self-injury with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in youth: Occurrence, predictors and timing. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145:209-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stawicka E, Wolańczyk T. Mania induced by antidepressants - characteristics and specific phenomena in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Pol. 2020;54:525-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patel R, Reiss P, Shetty H, Broadbent M, Stewart R, McGuire P, Taylor M. Do antidepressants increase the risk of mania and bipolar disorder in people with depression? A retrospective electronic case register cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Martin A, Young C, Leckman JF, Mukonoweshuro C, Rosenheck R, Leslie D. Age effects on antidepressant-induced manic conversion. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:773-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nuñez NA, Coombes BJ, Melhuish Beaupre L, Romo-Nava F, Gardea-Resendez M, Ozerdem A, Veldic M, Singh B, Sanchez Ruiz JA, Cuellar-Barboza A, Leung JG, Prieto ML, McElroy SL, Biernacka JM, Frye MA. Antidepressant-Associated Treatment Emergent Mania: A Meta-Analysis to Guide Risk Modeling Pharmacogenomic Targets of Potential Clinical Value. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2023;43:428-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Bailey AP, Sharma V, Moller CI, Badcock PB, Cox GR, Merry SN, Meader N. New generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5:CD013674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Reyad AA, Plaha K, Girgis E, Mishriky R. Fluoxetine in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Hosp Pharm. 2021;56:525-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Walter HJ, Abright AR, Bukstein OG, Diamond J, Keable H, Ripperger-Suhler J, Rockhill C. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Major and Persistent Depressive Disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62:479-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, Hetrick SE, Qin B, Whittington C, Coghill D, Zhang Y, Hazell P, Leucht S, Cuijpers P, Pu J, Cohen D, Ravindran AV, Liu Y, Michael KD, Yang L, Liu L, Xie P. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388:881-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 46.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Skapinakis P, Caldwell D, Hollingworth W, Bryden P, Fineberg N, Salkovskis P, Welton N, Baxter H, Kessler D, Churchill R, Lewis G. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pharmacological and psychological interventions for the management of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children/adolescents and adults. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20:1-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/