Published online Sep 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i9.1326

Revised: August 17, 2024

Accepted: August 27, 2024

Published online: September 19, 2024

Processing time: 49 Days and 19.2 Hours

Evaluating the psychological resilience of lung cancer (LC) patients helps understand their mental state and guides future treatment. However, there is limited research on the psychological resilience of LC patients with bone me

To explore the psychological resilience of LC patients with bone metastases and identify factors that may influence psychological resilience.

LC patients with bone metastases who met the inclusion criteria were screened from those admitted to the Third Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. The psychological scores of the enrolled patients were collected. They were then grouped based on the mean psychological score: Those with scores lower than the mean value were placed in the low-score group and those with scores equal to or greater than the mean value was placed in the high-score group. The baseline data (age, gender, education level, marital status, residence, monthly income, and religious beliefs), along with self-efficacy and medical coping mode scores, were compared.

This study included 142 LC patients with bone metastases admitted to our hospital from June 2022 to December 2023, with an average psychological resilience score of 63.24 ± 9.96 points. After grouping, the low-score group consisted of 69 patients, including 42 males and 27 females, with an average age of 67.38 ± 9.55 years. The high-score group consisted of 73 patients, including 49 males and 24 females, with a mean age of 61.97 ± 5.00 years. χ2 analysis revealed significant differences between the two groups in education level (χ2 = 6.604, P = 0.037), residence (χ2 = 12.950, P = 0.002), monthly income (χ2 = 9.375, P = 0.009), and medical coping modes (χ2 = 19.150, P = 0.000). Independent sample t-test showed that the high-score group had significantly higher self-efficacy scores (t = 3.383, P = 0.001) and lower age than the low-score group (t = 4.256, P < 0.001). Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression hazard analysis confirmed that self-efficacy is an independent protective factor for psychological resilience [odds ratio (OR) = 0.926, P = 0.035, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.862-0.995], while age (OR = 1.099, P = 0.003, 95%CI: 1.034-1.169) and medical coping modes (avoidance vs confrontation: OR = 3.767, P = 0.012, 95%CI: 1.342-10.570; resignation vs confrontation: OR = 5.687, P = 0.001, 95%CI: 1.974-16.385) were identified as independent risk factors. A predictive model based on self-efficacy, age, and medical coping modes was developed. The receiver operating characteristic analysis showed an area under the curve value of 0.778 (95%CI: 0.701-0.856, P < 0.001), indicating that the model has good predictive performance.

LC patients with bone metastases are less psychologically resilient than the general population. Factors such as self-efficacy, age, and medical coping modes influence their psychological resilience. Patients with low self-efficacy, old age, and avoidance/resignation coping modes should be closely observed.

Core Tip: We surveyed psychological resilience on lung cancer patients with bone metastases and found that their resilience level was low. It is confirmed that high self-efficacy is an independent protective factor for psychological resilience, while advanced age and poor medical coping modes are independent risk factors. The prediction model constructed based on these factors can be used to predict the psychological resilience of patients, providing a strong reference basis for clinical treatment and management.

- Citation: Guo CF, Wu LL, Peng ZZ, Lin HL, Feng JN. Study on psychological resilience and associated influencing factors in lung cancer patients with bone metastases. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(9): 1326-1334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i9/1326.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i9.1326

Lung cancer (LC) refers to tumors originating from the lung parenchyma or bronchi, which can be broadly classified as non-small-cell and small-cell LC based on histopathology, with the former being the most common subtype, accounting for 80%-85% of all LC patients[1-3]. According to the latest global cancer statistics, LC ranks first among all cancer types in terms of incidence and mortality[4]. The 5-year survival rate for LC patients is quite low, with a median survival of only 16.9 months in a prospective study of 8739 patients[5], highlighting the severe threat posed by LC. Distant metastases, particularly to bone tissue[6], are the major cause of death in LC patients, with 30%-40% of them experiencing bone metastases[7]. Bone metastases in LC can cause pain, pathological fractures, spinal instability, spinal cord com

According to the latest definition, psychological resilience is defined as the ability to effectively adapt to or navigate (or manage) traumatic stress or adversity, and to absorb disturbances while using resources efficiently[9]. It results from the collaborative work of multiple factors including both the brain and the body. When facing adversity, different factors interact and activate each other, thereby helping people maintain good mental health during adversity[10]. For cancer patients, psychological resilience is closely related to disease prognosis. Clinical data indicate that psychological resilience is positively correlated with quality of life and emotional adjustment ability[11]. In addition, good psychological resilience helps patients mitigate negative emotions and improve treatment compliance. Higher resilience enables patients to better adapt to changes in the external environment and adapt to new social roles, and promote the de

Bone metastases in LC can easily lead to emotional and psychological stress, which can reduce treatment compliance and affect treatment effectiveness. Evaluating psychological resilience in LC patients helps understand their mental state and guides future treatment planning. However, there is limited research on psychological resilience of LC patients with bone metastases. In view of this, this study intends to retrospectively analyze LC patients with bone metastases at our hospital, analyze the current situation of their psychological resilience, and explore potential factors that affect it.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on LC patients with bone metastases admitted to the Third Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University from June 2022 to December 2023. They were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Their psychological status scores were collected and averaged, and they were assigned to a low-score group (total psychological status score < mean value) and a high-score group (total psychological status score ≥ mean value). The sample size was calculated using powerandsamplesize.com, resulting in an estimate of 150 cases. Patients were recruited based on this sample size.

Inclusion criteria: Confirmed LC diagnosis by histopathological examination; bone metastases due to LC; education level > primary school, clear consciousness, and ability to communicate normally; age ≥ 18 years old; complete general information.

Exclusion criteria: Presence of cognitive impairment; unstable or rapidly deteriorating condition; other diseases or tumors; systemic immune system disorders; comorbid bone metabolism disorders including primary hyperparathyroidism, Paget’s disease, osteochondrosis, and osteogenesis imperfecta; breastfeeding or pregnancy; previous oncological treatment history.

Primary outcome measures: Psychological resilience score: The Conno-Davidson Resilience Scale scores of the patients were collected. There are 25 questions in the scale, each with a score of 0-4, indicating never, seldom, occasionally, often, and always, respectively. The total score on the scale ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. There are three concepts in the scale, i.e., tenacity (0-52 points), strength (0-24 points), and optimism (0-16 points), with a reliability coefficient of 0.929.

Secondary outcome measures: (1) Baseline data: Patients’ baseline data, including age, sex, education level, marital status, residence, monthly income, and religious beliefs, were collected from the hospital’s electronic medical record system; (2) Self-efficacy: Information on patients’ self-efficacy evaluation was also collected. In this study, self-efficacy was evaluated by using the General Self-Efficacy Scale developed by Schwarzer, a German clinical psychologist, with a reliability coefficient of 0.846. This single-dimensional 10-item is scored from 1 to 4 for each item, including not at all true, barely true, moderately true, and completely true, with a total score of 10-40; and (3) Medical coping modes: The evaluation results of the Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire short-form of patients were collected. The Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire scale includes three subscales, namely confrontation, avoidance, and resignation, with 20 items in total. Scoring was performed on a 4-point Likert scale, corresponding to a score of 1-4 for a total score of 20-80. The scores of the three subscales were compared, and the highest score determined the patient’s medical coping mode. The reliability coefficient of the scale is 0.942.

Data collection and verification process were independently completed by two researchers. One researcher conducted data induction and summary based on a pre-established manual, while the other reviewed the data, including data range, outliers, key dates and times, logical relationship contradictions between variables, missing data, etc. The final data and results were validated through group discussions.

This study used SPSS 25.0 software for statistical analysis and GraphPad 9.0 software for image rendering. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to investigate normality. The mean and standard deviation of measurement data were calculated and compared between groups using the independent sample t-test. Count data were expressed as cases (percentages), and the difference between the groups was compared using the χ2 test. Logistic regression hazard analysis was carried out using SPSS 25.0. In this analysis, the control and high-score groups were assigned a value of 1 and 0, respectively, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression hazard analyses were carried out in turn by including indicators with P < 0.05. Subsequently, a prediction model was constructed based on the identified factors, whose prediction value was then evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

A total of 142 LC patients with bone metastases were included in this study, comprising 91 males and 51 females, with an average total score of 63.24 ± 9.96. Sixty-nine patients with psychological resilience scores below 63.24 points were placed in the low-score group, comprising 42 males and 27 females, with an average age of 67.38 ± 9.55 years. The high-score group consisted of 73 patients with resilience scores ≥ 63.24, a male-to-female ratio of 49:24, and an average age of 61.97 ± 5.00 years. The low-score and high-score groups were not statistically different in terms of sex (χ2 = 0.603, P = 0.438), marital status (χ2 = 0.772, P = 0.680), and religious belief (χ2 = 0.369, P = 0.543); however, statistical inter-group differences were found in age (t = 4.256, P < 0.001), education level (χ2 = 6.604, P = 0.037), residence (χ2 = 12.950, P = 0.002), and monthly income (χ2 = 9.375, P = 0.009). The specific results are shown in Table 1.

| Low-score group (n = 69) | High-score group (n = 73) | χ2/t | P value | |

| Age (years old), mean ± SD | 67.38 ± 9.55 | 61.97 ± 5.00 | 4.256 | 0.000 |

| Sex | 0.603 | 0.438 | ||

| Male | 42 (60.87) | 49 (67.12) | ||

| Female | 27 (39.13) | 24 (32.88) | ||

| Education level | 6.604 | 0.037 | ||

| Senior high school or below | 31 (44.93) | 18 (24.66) | ||

| Junior college | 23 (33.33) | 31 (42.47) | ||

| Bachelor degree or above | 15 (21.74) | 24 (32.88) | ||

| Marital status | 0.772 | 0.680 | ||

| Single | 7 (10.14) | 9 (12.33) | ||

| Married | 49 (71.01) | 54 (73.97) | ||

| Divorced | 13 (18.84) | 10 (13.70) | ||

| Residence | 12.950 | 0.002 | ||

| Township and village level | 24 (34.78) | 19 (26.03) | ||

| County level | 27 (39.13) | 14 (19.18) | ||

| City level | 18 (26.09) | 40 (54.79) | ||

| Monthly income | 9.375 | 0.009 | ||

| CNY < 3000 | 33 (47.83) | 17 (23.29) | ||

| CNY 3000-5000 | 21 (30.43) | 32 (43.84) | ||

| CNY > 5000 | 15 (21.74) | 24 (32.88) | ||

| Religious belief | 0.369 | 0.543 | ||

| With | 12 (17.39) | 10 (13.70) | ||

| Without | 57 (82.61) | 63 (86.30) |

Table 2 shows that the high-score group outperformed the low-score group in tenacity (t = 10.116, P < 0.001), strength (t = 4.863, P < 0.001), optimism (t = 6.757, P < 0.001), and total psychological resilience (t = 16.250, P < 0.001), according to the independent sample t-test analysis.

| Low-score group (n = 69) | High-score group (n = 73) | t | P value | |

| Tenacity score | 28.72 ± 4.70 | 36.59 ± 4.56 | 10.116 | 0.000 |

| Strength score | 19.17 ± 4.87 | 22.77 ± 3.90 | 4.863 | 0.000 |

| Optimism score | 7.09 ± 4.31 | 11.68 ± 3.79 | 6.757 | 0.000 |

| Total psychological resilience score | 54.99 ± 5.90 | 71.04 ± 5.87 | 16.250 | 0.000 |

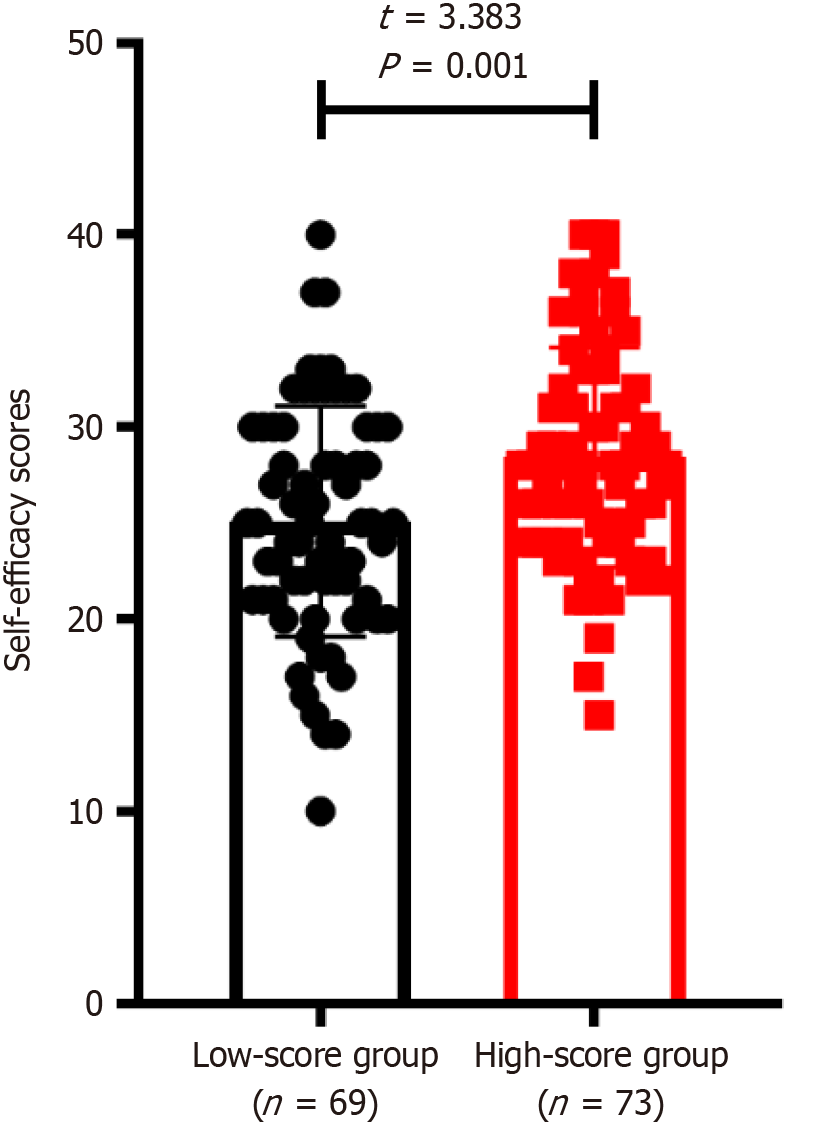

Figure 1 shows the self-efficacy score of the low-score group was 25.11 ± 6.00 and that of the high-score group was 28.44 ± 5.70; the inter-group comparison revealed an evidently higher score in the high-score group than the low-score group (t = 3.383, P = 0.001).

In the low-score group, 12, 25, and 32 patients adopted the coping mode of confrontation, avoidance, and resignation, respectively. In the high-score group, 38 patients adopted the confrontation mode, 18 patients used the avoidance mode, and 17 patients adopted the resignation mode. According to the χ2 test analysis, the research and low-score groups were significantly different in medical coping modes (χ2 = 19.150, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Low-score group (n = 69) | High-score group (n = 73) | χ2 | P value | |

| Confrontation | 12 (17.39) | 38 (52.05) | 19.150 | 0.000 |

| Avoidance | 25 (36.23) | 18 (24.66) | ||

| Resignation | 32 (46.38) | 17 (23.29) |

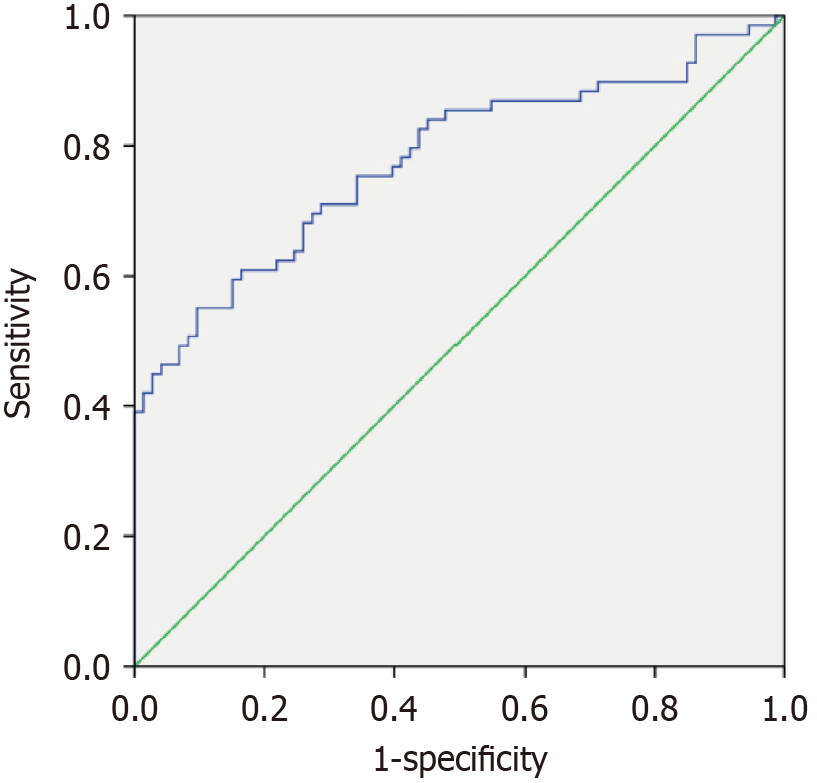

First of all, this study included indicators with P < 0.05 from results 4.1-4.4 for univariate logistic hazard analysis. The six indicators selected were education level, self-efficacy, residence, monthly income, medical coping modes, and age. As shown in Table 4, education level [junior college vs senior high school or below: Odds ratio (OR) = 0.431, P = 0.037, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.195-0.952; bachelor degree or above vs senior high school or below: OR = 0.363, P = 0.022, 95%CI: 0.152-0.865], self-efficacy (OR = 0.906, P = 0.002, 95%CI: 0.853-0.963), and monthly income (CNY 3000-5000 vs < 3000: OR = 0.338, P = 0.008, 95%CI: 0.151-0.755; CNY > 5000 vs < 3000: OR = 0.322, P = 0.011, 95%CI: 0.135-0.769), age (OR = 1.101, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 1.047-1.157), and medical coping modes (resignation vs confrontation: OR = 5.961, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 2.483-14.312; avoidance vs confrontation: OR = 4.398, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 1.810-10.687) may be factors influencing resilience. Subsequently, multivariate logistic hazard analysis was carried out on the above influencing factors. As shown in Table 5, self-efficacy was an independent protective factor for resilience (OR = 0.926, P = 0.035, 95%CI: 0.862-0.995), while age (OR = 1.099, P = 0.003, 95%CI: 1.034-1.169) and medical coping modes (avoidance vs confrontation: OR = 3.767, P = 0.012, 95%CI: 1.342-10.570; resignation vs confrontation: OR = 5.687, P = 0.001, 95%CI: 1.974-16.385) were independent risk factors. Finally, a prediction model was constructed based on self-efficacy, age, and medical coping modes, with its predictive value evaluated using ROC curves. As shown in Figure 2, the model had an area under the curve of 0.778 (95%CI: 0.701-0.856, P < 0.001), indicating good predictive performance and potential for assessing psychological resilience in LC patients with bone metastases.

| B | SE | Wals | df | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Education level | |||||||

| Junior college vs senior high school or below | -0.842 | 0.404 | 4.336 | 1 | 0.431 | 0.195-0.952 | 0.037 |

| Bachelor degree or above vs senior high school or below | -1.014 | 0.443 | 5.238 | 1 | 0.363 | 0.152-0.865 | 0.022 |

| Self-efficacy | -0.098 | 0.031 | 9.979 | 1 | 0.906 | 0.853-0.963 | 0.002 |

| Residence | |||||||

| County level vs township and village level | 0.423 | 0.450 | 0.883 | 1 | 1.527 | 0.632-3.690 | 0.347 |

| City level vs township and village level | -1.032 | 0.418 | 6.092 | 1 | 0.356 | 0.157-0.809 | 0.014 |

| Monthly income | |||||||

| CNY 3000-5000 vs < 3000 | -1.085 | 0.410 | 7.001 | 1 | 0.338 | 0.151-0.755 | 0.008 |

| CNY > 5000 vs < 3000 | -1.133 | 0.444 | 6.504 | 1 | 0.322 | 0.135-0.769 | 0.011 |

| Medical coping mode | |||||||

| Avoidance vs confrontation | 1.481 | 0.453 | 10.691 | 1 | 4.398 | 1.810-10.687 | 0.001 |

| Resignation vs confrontation | 1.785 | 0.447 | 15.957 | 1 | 5.961 | 2.483-14.312 | 0.000 |

| Age | 0.096 | 0.025 | 14.402 | 1 | 1.101 | 1.047-1.157 | 0.000 |

| B | SE | Wals | df | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Education level | |||||||

| Junior college vs senior high school or below | -0.967 | 0.502 | 3.718 | 1 | 0.380 | 0.142-1.016 | 0.054 |

| Bachelor degree or above vs senior high school or below | -1.371 | 0.549 | 6.240 | 1 | 0.254 | 0.087-0.744 | 0.012 |

| Monthly income | |||||||

| CNY 3000-5000 vs < 3000 | -1.152 | 0.494 | 5.434 | 1 | 0.316 | 0.120-0.832 | 0.020 |

| CNY > 5000 vs < 3000 | -0.969 | 0.532 | 3.319 | 1 | 0.380 | 0.134-1.076 | 0.068 |

| Self-efficacy | -0.077 | 0.037 | 4.451 | 1 | 0.926 | 0.862-0.995 | 0.035 |

| Age | 0.095 | 0.031 | 11.197 | 1 | 1.099 | 1.034-1.169 | 0.003 |

| Medical coping mode | |||||||

| Avoidance vs confrontation | 1.326 | 0.526 | 6.346 | 1 | 3.767 | 1.342-10.570 | 0.012 |

| Resignation vs confrontation | 1.738 | 0.540 | 10.364 | 1 | 5.687 | 1.974-16.385 | 0.001 |

LC is associated with a high incidence, low survival rate, and poor prognosis. Psychological resilience is a relatively new concept describing the ability to return to a normal or healthy state after trauma, accidents, tragedies, or diseases[12-14]. Higher psychological resilience is linked to a stronger treatment enthusiasm, which positively impacts treatment effectiveness. This found that LC patients with bone metastases generally have low psychological resilience. It confirmed that high self-efficacy is an independent protective factor, while advanced age and poor medical coping modes are independent risk factors.

In this study, 142 patients were assessed for their psychological status. Their psychological resilience score was 63.24 ± 9.96 points, which is lower than that of the general population[15,16]. LC is a common malignancy that often leads to significant psychological burdens, including anxiety and depression, due to its treatment and survival challenges. Additionally, LC frequently results in bone metastases, which cause pain and increase the risk of fractures. In severe cases, cancer cells with bone metastases invade the spinal cord, increasing the risk of paralysis[17]. The combined effects of LC and bone metastases can create significant psychological pressure and decrease psychological resilience, which may be the reason why psychological resilience scores in LC patients with bone metastases are lower compared to those of the general population. Clinically, it is necessary to regularly evaluate the psychological status of LC patients with bone metastases and strengthen the dissemination of health knowledge to them and their families, to maintain their psychological well-being.

This study found that the higher the self-efficacy, the higher the psychological resilience. A cross-sectional study of 143 elderly people pointed out that high self-efficacy can improve psychological resilience[18]. Zeng et al[19] found a significant positive correlation between self-efficacy and psychological resilience, indicating that increased self-efficacy improves psychological resilience. The above evidence indicates that self-efficacy positively impacts psychological resilience to a certain extent. Additionally, psychological resilience may also affect the patient’s subsequent self-efficacy. Clinical data suggest that patients with higher resilience also tend to have greater self-efficacy compared with those with lower resilience[20]. Thus, psychological resilience and self-efficacy can influence each other, synergistically alleviating patients’ negative emotions when dealing with diseases and increasing their treatment enthusiasm.

This study confirmed that older age and avoidance/resignation coping modes can decrease psychological resilience. Clinical evidence has shown that psychological resilience tends to decline with age[21,22]. Older patients often face a decline in organ function and overall physical fitness, leading to age-related changes that can reduce psychological resilience. Medical coping modes refer to the cognitive regulation and behavioral efforts taken by patients when facing medical-related stress events, which play an important role in the disease treatment process[23]. A systematic review found that positive medical coping modes improve treatment outcomes by enhancing medication adherence[24]. Recent studies in LC have shown that positive coping strategies can enhance psychological resilience[25]. This study highlights the need for increased attention to elderly LC patients with bone metastases and those with poor medical coping modes to help them maintain good psychological resilience. Subsequently, a joint prediction model based on self-efficacy, age, and medical coping modes was constructed to predict the psychological resilience in LC patients with bone metastases. The ROC curve results indicated good diagnostic performance of the joint model, which confirms that self-efficacy, age, and medical coping modes are closely related to the psychological resilience level of LC patients with bone metastases.

Our findings suggest that patients with low self-efficacy, old age, and avoidance/resignation coping modes should be closely observed. Also, implementing health education programs for the elderly can improve awareness regarding the disease, thereby facilitating the development of positive medical coping strategies in this demographic. Alternatively, psychological counseling services and mental health lectures may also be beneficial in enhancing self-efficacy of elderly patients.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a single-center study with a limited sample size, which prevents us from validating the predictive model internally. Therefore, we plan to engage in in-depth cooperation with other hospitals in future research and include larger sample sizes through multicenter studies. Second, while LC can be categorized into types such as non-small-cell LC and large cell LC, this study did not explore the relationship between the prediction model and different LC types when grouping. Therefore, it is necessary to further divide and group LC patients with bone metastases. Third, the present study was a retrospective analysis, which may have introduced the following limitations: (1) The potential for selection bias and recall bias; (2) The possible changes in the definition of symptoms and diseases; and (3) The limited information of patients. Given these, a prospective study in the future is needed to validate our findings. Also, this study did not explore the relationship between time lapse and patients’ psychological resilience. A longitudinal study is needed to observe the changes in psychological resilience at admission, before treatment, and after treatment.

This study reveals the current status of psychological resilience of LC patients with bone metastases and confirms that self-efficacy, age, and medical coping modes are independent factors influencing psychological resilience. The prediction model constructed based on these factors can be used to predict the psychological resilience of patients, providing a strong reference basis for clinical treatment and management.

| 1. | Xie X, Li X, Tang W, Xie P, Tan X. Primary tumor location in lung cancer: the evaluation and administration. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;135:127-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wen H, Liang C. Effects of Lobectomy versus Sub-Lobar Resection on the Survival in Adults with Stage IA Left Upper Lobe Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study Based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Oncology. 2024;102:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Leiter A, Veluswamy RR, Wisnivesky JP. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:624-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 783] [Article Influence: 261.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12727] [Article Influence: 6363.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 5. | Luo YH, Luo L, Wampfler JA, Wang Y, Liu D, Chen YM, Adjei AA, Midthun DE, Yang P. 5-year overall survival in patients with lung cancer eligible or ineligible for screening according to US Preventive Services Task Force criteria: a prospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1098-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu S, Pan Y, Mao Y, Chen Y, He Y. Current progress and mechanisms of bone metastasis in lung cancer: a narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10:439-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang X, Shi X, Huang D, Li B, Lin N, Pan W, Yan X, Li H, Hao Q, Ye Z. Mutational characteristics of bone metastasis of lung cancer. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:8818-8826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kähkönen TE, Halleen JM, MacRitchie G, Andersson RM, Bernoulli J. Insights into immuno-oncology drug development landscape with focus on bone metastasis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1121878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McManama O'Brien KH, Rowan M, Willoughby K, Griffith K, Christino MA. Psychological Resilience in Young Female Athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smeeth D, Beck S, Karam EG, Pluess M. The role of epigenetics in psychological resilience. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:620-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Groarke A, Curtis R, Skelton J, Groarke JM. Quality of life and adjustment in men with prostate cancer: Interplay of stress, threat and resilience. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tamura S, Suzuki K, Ito Y, Fukawa A. Factors related to the resilience and mental health of adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:3471-3486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zábó V, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Purebl G. Psychological resilience and competence: key promoters of successful aging and flourishing in late life. Geroscience. 2023;45:3045-3058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Choi KW, Stein MB, Dunn EC, Koenen KC, Smoller JW. Genomics and psychological resilience: a research agenda. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:1770-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4591] [Cited by in RCA: 5640] [Article Influence: 256.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vaishnavi S, Connor K, Davidson JR. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Res. 2007;152:293-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Clézardin P, Coleman R, Puppo M, Ottewell P, Bonnelye E, Paycha F, Confavreux CB, Holen I. Bone metastasis: mechanisms, therapies, and biomarkers. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:797-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Remm SE, Halcomb E, Peters K, Hatcher D, Frost SA. Self-efficacy, resilience and healthy ageing among older people who have an acute hospital admission: A cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. 2023;10:7168-7177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zeng W, Wu X, Xu Y, Wu J, Zeng Y, Shao J, Huang D, Zhu Z. The Impact of General Self-Efficacy on Psychological Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Growth and the Moderating Role of Deliberate Rumination. Front Psychol. 2021;12:684354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kuang D, Gu DF, Cao H, Yuan QF, Dong ZX, Yu D, Shen XM. Impacts of psychological resilience on self-efficacy and quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective cross-sectional study. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:5610-5618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lenti MV, Brera AS, Ballesio A, Croce G, Padovini L, Bertolino G, Di Sabatino A, Klersy C, Corazza GR. Resilience is associated with frailty and older age in hospitalised patients. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li Y, Xie P, He L, Fu X, Ding X, Jobe MC, Ahmed MZ. The effect of perceived stress for work engagement in volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of psychological resilience and age differences. PeerJ. 2023;11:e15704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:992-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chatoo A, Lee S. Association of Coping Strategies and Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review. Innov Pharm. 2022;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Yin Y, Lyu M, Chen Y, Zhang J, Li H, Li H, Xia G, Zhang J. Self-efficacy and positive coping mediate the relationship between social support and resilience in patients undergoing lung cancer treatment: A cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2022;13:953491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/