Published online Sep 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i9.1294

Revised: August 17, 2024

Accepted: August 21, 2024

Published online: September 19, 2024

Processing time: 65 Days and 11.9 Hours

Gynecological cancers and their treatments are associated with both specific and non-specific long-term physiological effects. Cancer patients face transformations in their lifestyle, body image, role, and social interactions and suffer from physical, psychological, and economic problems. The mental health of cancer patients is of great importance and requires special attention, as growing evidence demonstrates its influence not only on quality of life but also on treatment com

Core Tip: The moment a gynecological cancer takes hold of a woman’s body marks a total invasion of her entire existence. These patients often experience deep psychological distress and undergo one of the most traumatic experiences of their lives, starting with the diagnosis and continuing with subsequent treatments. This picture is associated with psychological and emotional responses such as anxiety, anger, guilt, despair, uncertainty, loneliness, fear, difficulty accepting the disease, and loss of sexual desire. It is beneficial for psychological work to stimulate the post-traumatic growth experienced and reported by the patient, both in personal and relational terms.

- Citation: Marano G, Mazza M. Impact of gynecological cancers on women’s mental health. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(9): 1294-1300

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i9/1294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i9.1294

In the work of Shang et al[1], it was observed that patients with gynecological malignancies often experience anxiety and depression and that the traumatic experience of a gynecological tumor or undergoing treatment greatly affects quality of life. Every serious illness, such as cancer, wounds and leaves a mark on both body and mind. However, there are some neoplastic diseases that, more than others, heavily mark the existence of the people affected[2].

The female reproductive system, synonymous with life and its continuation, is not immune to a disease as insidious as cancer, whose nature not only jeopardizes a woman’s inherent ability to conceive and generate new life but also the woman’s very survival.

Gynecological cancer, in this regard, emerges as the most representative type. When the uninvited growth emerges where a woman defines her very being, the wounds to be mended extend beyond the surface, delving deep, carving, and healing with immense struggle. A woman’s gender identity, shaped by roles she has played or could play, such as partner, wife, or mother, is abruptly thrown into disarray. In addition to the frequent physical mutilations resulting from surgical treatment, in the particular case of gynecological cancer, there are feelings of “betrayal” experienced by the body itself, with a violation of the intimate sphere, devastated and injured[3,4].

Radical surgical procedures (such as hysterectomy), generally preceded or followed by radiation therapy or chemotherapy, not only cause the inability to procreate but also have significant hormonal effects, leading to induced early menopause and non-physiological imbalances and triggering further mood disorders. The surgery can be perceived by the woman as a traumatic separation from her natural biological rhythms. For instance, the menstrual cycle, a distinctive feature of femininity imbued with profound symbolic significance, is suddenly suppressed, generating feelings of loss and inadequacy. For women, appearance plays a crucial role in their relationships, intimacy, and sexuality. The latter undergoes a transformation, morphing from a cherished haven of personal security, where one can reveal oneself without fear or shame, into a treacherous landscape exuding insecurity and often fear of contact[5]. The upheaval of every aspect of being a woman, from the strictly gynecological and hormonal to the aesthetic and deeply intimate, takes shape as an altered quality of life and is characterized by significant psychological distress that is linked to the challenging adaptation to the diagnosis and all that entails[6]. Women with gynecologic tumors are a distinctive group of oncological patients with peculiar needs that require personalized management. Their cancer board should be multidisciplinary, involving many professional figures, including endocrinologists, oncofertility experts, psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers, with the aim to help oncologists to manage patients’ gynecologic specific issues and psychosocial effects[7].

Gynecological cancers are neoplasms that affect the female reproductive system. There are different disorders with different symptoms, treatments, and prognoses. They include ovarian, vulvar, vaginal, endometrial, and cervical cancers. The high mortality rate from gynecological malignancies highlights the need for improved public health measures to prevent and detect these diseases. The burden of gynecological cancers is felt across the globe. These cancers represent a major threat, accounting for nearly 40% of all new cancers diagnosed and over 30% of all cancer deaths in females worldwide. With an estimated 3.6 million new cases and a death toll exceeding 1.3 million, these cancers are a significant public health concern[8,9].

Moreover, the number of females being diagnosed with cancer is steadily rising, a consequence of the population aging that is occurring in much of the world. There is a growing prevalence of risk factors (e.g., obesity), which in turn increase the incidence of gynecological cancers such as endometrial cancer[10]. Less developed countries account for more than 80% of the cervical cancer cases, while almost 60% of uterine corpus cases occur in the developed world. In low-resource and medium-resource countries, accessibility to health services and inadequate development of screening and vaccination programs are still present. This disparity leads to observed differences in the outcome of cancer treatment across the world[11].

The epidemiological patterns of gynecological cancers differ in various regions and alter over time. In fact, differences in both incidence and survival rates among racial and ethnic groups have been registered. For example, African American women have been found to experience higher mortality rates and worse survival outcomes in relation to incidence compared to Caucasian women for various reproductive cancers. These disparities could be related to diversified access to healthcare, socioeconomic factors, differences in tumor biology, and variations in treatment responses[12]. Increased ages have a negative prognosis in cervical cancer and ovarian cancer, while patients younger than 45-years-old with endometrial cancer had a reduced incidence of advanced-stage tumors, better prognosis, and elevated tumor differentiation[13].

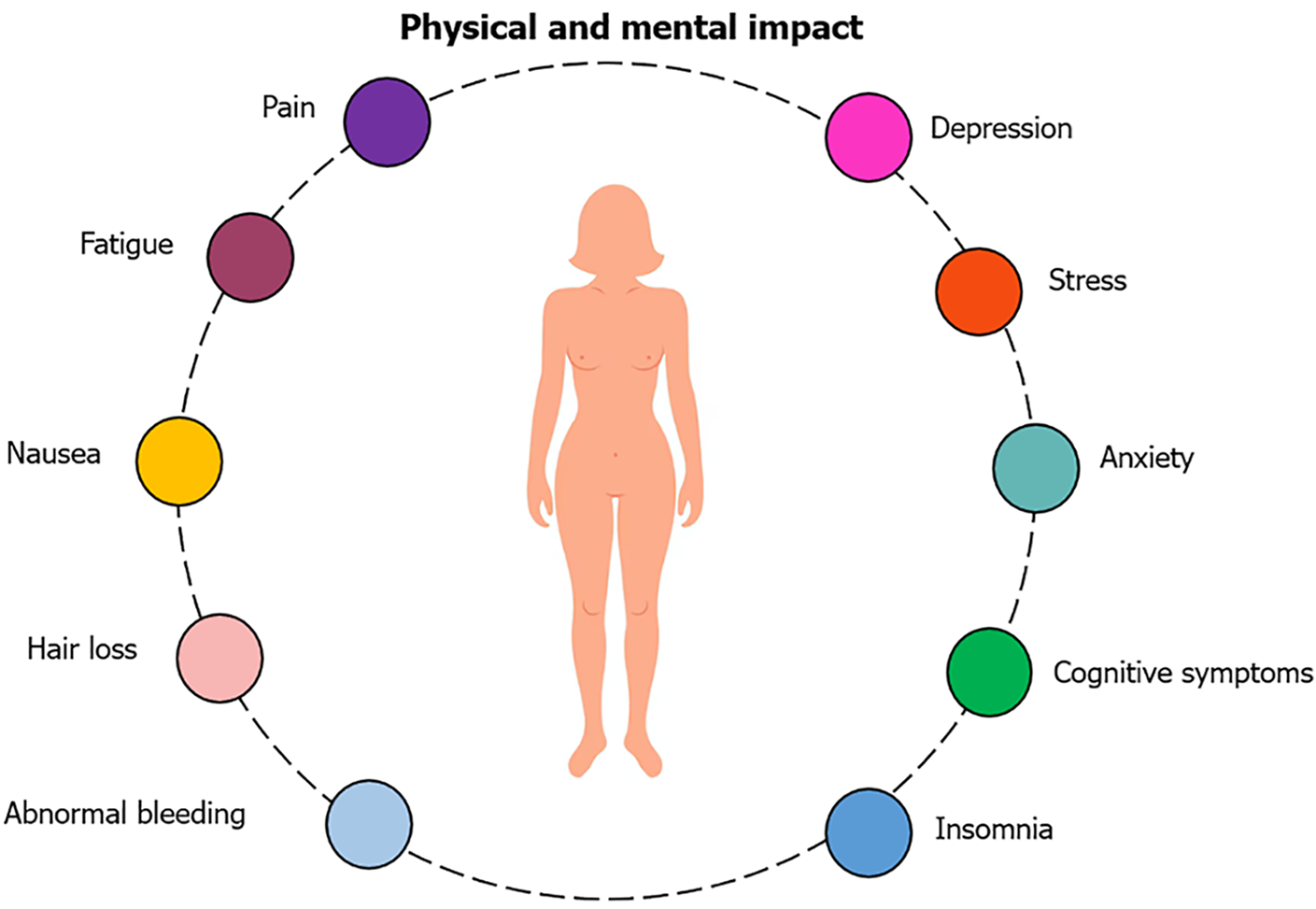

Women with gynecological cancers experience significant physical and psychological burdens. The interconnected nature of physical symptoms and their corresponding mental health manifestations emphasizes the importance of integrated care that addresses both physical and mental health needs (Figure 1).

Gynecological cancers and their treatments are associated with both specific and non-specific long-term physiological effects. Indeed, in addition to the experiences common to almost all patients with cancer undergoing treatment (pain, fatigue, anxiety, hair loss, etc.), gynecological cancer can lead to specific problems such as: Surgically or chemically induced menopause; infertility; sexual dysfunction; incontinence; and psychological and emotional disturbances related to body image, sexuality, and relationships[14].

The side effects of therapies, in addition to impacting the patient’s health status, often overlap. It is common, in fact, for females to face the cumulative effects of radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy in the midst of the surgical recovery phase. Other treatment-related effects include anatomical changes such as vaginal shortening, decreased vaginal elasticity, pelvic nerve damage, clitoridectomy, vaginal stenosis, and physical changes such as reduced physical function, fatigue, diarrhea, dyspareunia, and postcoital bleeding. Other effects comprise changes in sexuality, with modifications in desire, orgasm, arousal, and lubrication. These changes may be associated with a decrease in the frequency of sexual relations. Moreover, even after undergoing surgery and chemotherapy, the chances of recurrence are relatively high[15]. There are females who experience significant declines or improvements in mental health in the years following diagnosis. Factors associated with better adjustment have included older age, being married or partnered, greater optimism, greater self-efficacy, better social support, less rigorous chemotherapy, less pain, and less intrusion of illness on daily life[16].

Cancer is not merely a medical diagnosis of uncontrolled cell proliferation. The moment the disease takes hold of a woman’s body marks a total invasion of her entire existence. Fear is an unwelcome yet unstoppable force that permeates every aspect of her daily routine. The fear that cancer equals death materializes in thoughts and can take full possession of a patient’s internal dialogue. The fear of dying is accompanied by other fears, which are also common among all patients with cancer. Another fear is becoming disabled and dependent on others. There is also uncertainty about the current capabilities of medicine as well as concerns about the impact of cancer and its treatments on one’s life plans and physical well-being. In addition to the general fear of death, there is also the more specific fear of a painful and agonizing end, different from what was always imagined and desired, even if in the distant future[17].

Cancer patients face transformations in their lifestyle, body image, role, and social interactions as well as physical, psychological, and economic problems related to treatments and their condition. In addition to the profound life changes that patients must face, the reason these individuals often experience deep psychological distress is the awareness that the disease implies the possibility of experiencing pain and death. Cancer patients undergo one of the most traumatic experiences of their lives, starting with the diagnosis and continuing with subsequent treatments.

This picture is associated with psychological and emotional responses such as anxiety, anger, guilt, despair, uncertainty, loneliness, fear, difficulty accepting the disease, and loss of sexual desire. Cancer patients therefore experience a wide range of psychological symptoms, including anxiety and depression, which are more common in this population than in the general population. These individuals are also at high risk of suicide, especially when they are informed of the diagnosis or hospitalized for treatment. Cancer, therefore, is also a mental and psychosocial phenomenon that involves many problems in these areas[18].

It has been observed that cancer type, survivorship stage, and health-related behaviors were related to the risk of developing mental health problems. In particular, the risk of developing anxiety disorders seems to be increased in those who experienced cervical cancer compared to breast cancer, and the risk of depressive disorders increased in the order of those who experienced ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, and cervical cancer compared to breast cancer. In addition, the risk of developing depressive disorders tend to increase in the acute and extended stages, in current smokers, and in subjects who practice insufficient physical activity[19]. Patients with gynecological cancer have an increased suicide risk when compared to the general population, with the highest suicide rates observed in patients with ovarian cancer and within the first year following diagnosis[20].

The mental health of cancer patients is of great importance and requires special attention, as growing evidence demonstrates its influence not only on quality of life but also on treatment compliance. Of far greater significance and serious connotation, however, are those responses to the diagnosis that evolve into disorders, classifiable as true psychopathological syndromes such as adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and psychotic disorders. Indeed, the presence of psychiatric problems, sometimes already present, are emphasized and made salient by the cancer diagnosis and are not a remote possibility but rather a more concrete one, concomitant with cancer[21].

The sensation of being completely and utterly overwhelmed by cancer as an unwelcome and unexpected guest is extremely common in families where, suddenly, a loved one falls ill with cancer. The family, a place to retreat and feel safe and accepted, is also the vital space that welcomes the diagnosis, shares it, and makes it its own, often without any will, by virtue of an intrinsic force that touches everyone, that disrupts and permeates, and that changes balances and threatens.

Sometimes a cancer diagnosis tends to bring families together, creating a common front against the enemy to be fought. But it is not uncommon for the cancer diagnosis to become entangled in the foundations of the family, which may not be as solid as they appear, creating small lesions that are destined to become dangerous fissures. A trauma, such as the advent of cancer, can have the potential to transform in a disruptive and often definitive way, the balances and adaptive processes of that specific living context in which the suffering person is immersed, which is called family[22].

Neoplastic disease serves as a paradigmatic example of the developmental crisis that every family is destined to face, in the transition from illusory expectations of an enduring bond to a mature awareness of the complexity, transience, and ambiguity of emotional relationships throughout the course of existence. The cultivation of family reciprocity, coupled with resilience, is often the decisive factor that saves from destruction and leads to fortification. Within the domestic nest, the various members can create a shared space of support and mutual exchange, in which an active awareness of the other, of one’s own influence on the other, and of the capacity for emotional contact with them becomes salient. The effort to increase reciprocity, and therefore emotional union, helps the patient to regain what has been lost and to pursue with a stronger and more authentic motivation the goal of connection with each member.

Certain family types may be more prone to distress and destabilization including cohabiting couples, single-parent families, and divided, extended, reconstructed, and gutted families. It is not uncommon for extremely small, isolated families, lacking the support and potential inherent in reciprocity, to have to confront the pain and suffering arising from a cancer diagnosis. These “fragile” families are further weighed down by the prolonged period of suffering and illness over time, which completely weighs on them[23].

Cancer strikes a woman in her role as a mother. Being a mother is not just a role but also an identity. The condition of being an oncology patient, often invaded by cancer in the very womb that has generated, nourished, and given birth, is often experienced as devastating. The difficulty in managing parenthood is, for oncology patients, among the most disturbing psychological aspects, strongly connected to the impossibility of taking care of children, protecting them, watching them grow and face the stages that life proposes, abandoning them, and leaving them alone[24].

It is beneficial for psychological work to stimulate the post-traumatic growth experienced and reported by the patient, both in personal and relational terms. This growth unfolds in the reformulation and positive modeling of one’s own cognitions, beliefs, and ways of thinking and giving meaning to events, loving oneself more (sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem), loving others (better relationships, more unity, more importance, more time dedicated), and loving the world (greater attachment to life).

In the aftermath of the trauma, phenomena and emotions take on a new light, being reevaluated in a positive perspective. Painful memories, past or present, by virtue of functional and deliberate communication and sharing of the disease and the importance attributed to the unsuppressed expression of emotions, both within and outside the family system, are not erased nor are they denied. They become a resource for personal and systemic growth, from which to draw to redefine oneself in a perspective of priority, unity, and revenge[25].

The entry on stage of the sick and suffering body can compromise the sense of psychosomatic unity and mind-body integration and disrupt the body’s own symbolization capacities, making it an “enemy body” source of painful feelings of helplessness and alienation. The trauma caused by serious illnesses limits future prospects, inevitably redimensioning them and on the other hand allows for a rethinking of one’s own subjective history from which new potentialities can develop, not only of thought but also of pleasure.

The onset of serious illnesses can expose individuals to distressing anxieties about death, which can lead to intense regressions. Facing illness and death alone can be so distressing that it can disrupt the relationship with the good internal object, leading to the development of paranoid anxiety that further reinforces the sense of loneliness and abandonment. This can intensify the anxiety caused by the illness to the point of paralysis and the inability to love or think. For patients with serious illnesses, the contribution that psychological work can provide is fundamental, as presence and listening, emotional acceptance, sharing, and affective warmth can bring great relief. The relationship and affective participation represent primary therapeutic factors in the recovery of the patient’s vital potential[26].

The experiences of pain and anguish triggered by serious illnesses can be so deeply ingrained and withdrawn from processing that they are unspeakable, yet they have a lasting effect on the subject’s development and sense of self. Yet, the presence and closeness of a psychotherapist can rekindle a reparative desire and unleash a vitality that persists despite the painful wounds and scars. In cases like this, the task of psychological work becomes the support of the patient’s resilience, the recovery of positive feelings, and the desire for vital experiences that survive despite the traumatic impact of the illness[27].

The illness of the body can instantly create an unexpected and long-unthinkable psychic wound. The extent the psychotherapist’s active listening, humanly vibrant and emotionally sound, can open up the path to a possibility of symbolization, transformation, and subjectivation of the trauma, an intruder “other than oneself”[22].

The economic impact of gynecological cancers is significant and increasing. It has been outlined that cancer prevention and control interventions are cost-effective and can significantly reduce the burden of disease globally. In particular, interventions for early-stage cancers are generally more cost-effective than those for late-stage cancers, and palliative care programs can be implemented at generally low costs. Effective cancer control planning requires accurate data for planning and could be implemented through a stepwise approach to achieve maximum health benefits[28].

Early detection and primary and secondary prevention of gynecological cancers is a very important issue, but the acknowledgement of challenges faced by the survivors at different levels of diagnoses and treatment are equally fundamental. Psychological well-being is a crucial part of the survivor’s journey through cancer diagnosis and treatment and advanced care plans and establishment of patient wishes early in patient management and may ultimately improve the mental struggles faced by affected women[29].

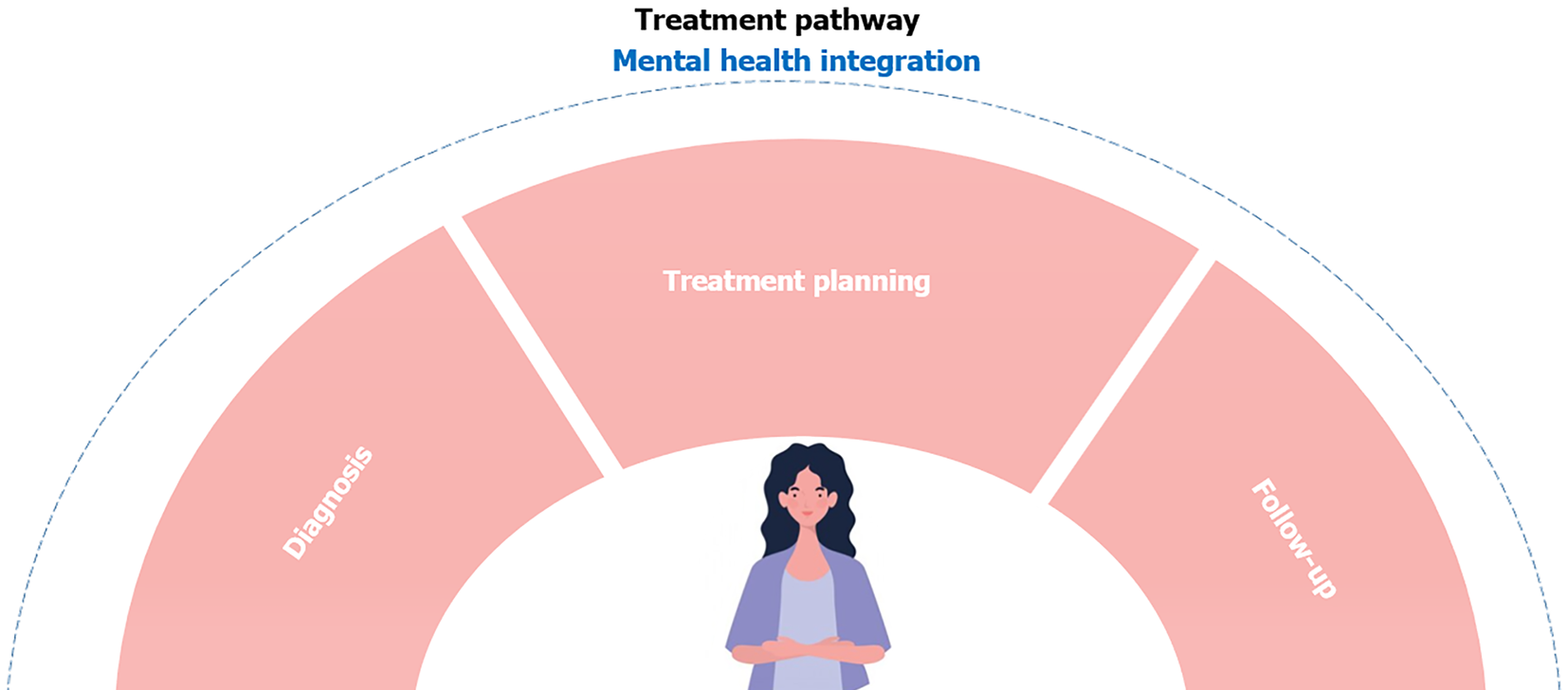

Psycho-oncology, therefore, matures within a broader context of medical transformation, where the ultimate goal is to provide patients with personalized treatment that takes into account not only the severity of the disease but also the individual as a whole, with their expectations, concerns, and psychological needs. Psycho-oncology focuses on the reactions to the specific event of the patient’s illness and the psychological, social, and behavioral variables that influence prevention, adherence to treatment, and quality of life. Psycho-oncology plays an essential role throughout the entire cancer continuum, accompanying patients at every stage of their journey: From prevention (primary and secondary) and preclinical cancer (known genetic risk or positive tumor markers in the absence of clinical disease) through diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship to palliative and end-of-life care[30,31].

Oncological diseases have a significant impact on the mental health and quality of life of patients. Gynecological cancers, in particular, have peculiar psychological consequences, linked to the specificity of the site of the neoplasia. It is therefore important that clinicians are aware of the importance of protecting the psychophysical health of these patients and the fact that their physical health and quality of life also depend on the quality of their mental health. Personal preferences towards the different techniques of psychosocial interventions impact the effectiveness of treatment. Mindfulness and cognitive therapies seem to have more evidence in literature[32], and recently online interventions have been increasingly used as clinically promising interventions to promote health outcomes among patients with gynecological cancer[33].

Key stages involved in the treatment pathway for patients with gynecological cancers highlight the integration of mental health support throughout the process. The pathway begins with diagnosis and its associated emotional impact, followed by treatment planning, which includes surgical, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy options. Mental health professionals intervene throughout the entire journey, with ongoing monitoring during follow-up care (Figure 2).

An effective assessment focused on the constructs recognized as most at risk allows for the knowledge of the psychological condition of the patients; consequently, it is possible to structure targeted and effective prevention interventions and if necessary treatment to reduce psychological distress and improve the quality of life of subjects living with a chronic disease such as cancer.

| 1. | Shang HX, Ning WT, Sun JF, Guo N, Guo X, Zhang JN, Yu HX, Wu SH. Investigation of the quality of life, mental status in patients with gynecological cancer and its influencing factors. World J Psychiatry. 2024;14:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Marano G, Gaetani E, Sani G, Mazza M. Body and Mind. Heart Mind. 2021;5:161-162. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mazza M, Marano G, Traversi G, De Simone G, Gaetani E, Paris I, Sani G, Mazza M. Emotional Health and Mental Coaching: Safeguarding Oncological Patients’ Mental Health in the COVID-19 Era. Clin Oncol Res. 2021;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Moran HK, Spoozak L, Brooks JV. "A Mission and Purpose to Make Some Sense out of Everything That Was Happening to Me": A Qualitative Assessment of Mentorship in a Peer-to-Peer Gynecologic Cancer Program. J Cancer Educ. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Marano G, Traversi G, Mazza M. Web-mediated Counseling Relationship in Support of the New Sexuality and Affectivity During the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Continuum Between Desire and Fear. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50:753-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Eaton L, Kueck A, Maksut J, Gordon L, Metersky K, Miga A, Brewer M, Siembida E, Bradley A. Sexual Health, Mental Health, and Beliefs About Cancer Treatments Among Women Attending a Gynecologic Oncology Clinic. Sex Med. 2017;5:e175-e183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Triarico S, Capozza MA, Mastrangelo S, Attinà G, Maurizi P, Ruggiero A. Gynecological cancer among adolescents and young adults (AYA). Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Priyadarshini S, Swain PK, Agarwal K, Jena D, Padhee S. Trends in gynecological cancer incidence, mortality, and survival among elderly women: A SEER study. Aging Med (Milton). 2024;7:179-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68314] [Article Influence: 13662.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 10. | Clontz AD, Gan E, Hursting SD, Bae-Jump VL. Effects of Weight Loss on Key Obesity-Related Biomarkers Linked to the Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sankaranarayanan R, Ferlay J. Worldwide Burden of Gynecological Cancer. Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures. New York: Springer, 2010. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Doddi S, Salichs O, Mushuni M, Kunte S. Demographic disparities in trend of gynecological cancer in the United States. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:11541-11547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Keyvani V, Kheradmand N, Navaei ZN, Mollazadeh S, Esmaeili SA. Epidemiological trends and risk factors of gynecological cancers: an update. Med Oncol. 2023;40:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fujiwara K, Connor SR, Fujiwara N, Correa R, Mburu A, Leopold D, Eiken M, Pearl ML. The International Gynecologic Cancer Society consensus statement on palliative care. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2024;34:1128-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:4-12. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Naughton MJ, Weaver KE. Physical and mental health among cancer survivors: considerations for long-term care and quality of life. N C Med J. 2014;75:283-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Paley CA, Boland JW, Santarelli M, Murtagh FEM, Ziegler L, Chapman EJ. Non-pharmacological interventions to manage psychological distress in patients living with cancer: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2023;22:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tounkel I, Nalubola S, Schulz A, Lakhi N. Sexual Health Screening for Gynecologic and Breast Cancer Survivors: A Review and Critical Analysis of Validated Screening Tools. Sex Med. 2022;10:100498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim SY, Lee Y, Koh SB. Factors Affecting the Occurrence of Mental Health Problems in Female Cancer Survivors: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mahdi H, Swensen RE, Munkarah AR, Chiang S, Luhrs K, Lockhart D, Kumar S. Suicide in women with gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pace R, Goldstein KM, Williams AR, Clayton-Stiglbauer K, Meernik C, Shepherd-Banigan M, Chawla N, Moss H, Skalla LA, Colonna S, Kelley MJ, Zullig LL. The Landscape of Care for Women Veterans with Cancer: An Evidence Map. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Marano G, Mazza M. Eros and Thanatos between individual wounds and social lacerations: Caring the Traumatized Self. J Loss Trauma. 2024;29:474-477. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hwang IY, Woo GU, Lee SY, Yoo SH, Kim KH, Kim MS, Shin J, Jeong HJ, Jang MS, Baek SK, Jung EH, Lee DW, Cho B. Home-based supportive care in advanced cancer: systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024;14:132-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Romare Strandh M, Enebrink P, Stålberg K, Sörensdotter R, Ljungman L, Wikman A. Parenting under pressure: a cross-sectional questionnaire study of psychological distress, parenting concerns, self-efficacy, and emotion regulation in parents with cancer. Acta Oncol. 2024;63:468-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Benedict C, Ford JS, Schapira L, Davis A, Simon P, Spiegel D, Diefenbach M. Preliminary testing of "roadmap to parenthood" decision aid and planning tool for family building after cancer: Results of a single-arm pilot study. Psychooncology. 2024;33:e6323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Uccellini O, Benlodi A, Caroppo E, Cena L, Esposito G, Fernandez I, Ghazanfar M, Imbasciati A, Longo F, Mazza M, Marano G, Nacinovich R, Pignatto A, Rolnick A, Trivelli M, Spada E, Vanzini C. 1000 Days: The "WeCare Generation" Program-The Ultimate Model for Improving Human Mental Health and Economics: The Study Protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Borghi S, Nisticò A, Marano G, Janiri L, Sani G, Mazza M. Beneficial effects of a program of Mindfulness by remote during COVID-19 lockdown. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:5562-5567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ralaidovy AH, Gopalappa C, Ilbawi A, Pretorius C, Lauer JA. Cost-effective interventions for breast cancer, cervical cancer, and colorectal cancer: new results from WHO-CHOICE. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2018;16:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Roy K, Riba MB. Cancer in Women and Mental Health. Mental Health and Illness Worldwide. Singapore: Springer, 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Zahid N, Asad N, El-Metwally A. Editorial: Resilience, quality of life and psychosocial outcomes of cancer patients and their caregivers. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1324977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mullen L, Signorelli C, Nekhlyudov L, Jacobsen PB, Gitonga I, Estapé T, Lim Høeg B, Miles A, Sade C, Mazariego C, Degi CL, Howard F, Manne S, Travado L, Jefford M; International Psycho-Oncology Society Survivorship Special Interest Group. Psychosocial care for cancer survivors: A global review of national cancer control plans. Psychooncology. 2023;32:1684-1693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cedenilla Ramón N, Calvo Arenillas JI, Aranda Valero S, Sánchez Guzmán A, Moruno Miralles P. Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Fatigue: An Umbrella Review. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:2954-2977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lin H, Ye M, Chan SW, Zhu J, He H. The effectiveness of online interventions for patients with gynecological cancer: An integrative review. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |