Published online Aug 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i8.1199

Revised: June 13, 2024

Accepted: June 24, 2024

Published online: August 19, 2024

Processing time: 96 Days and 20.2 Hours

Surgery is an effective method for treating certain diseases. Factors such as disease, preoperative fear and tension, surgical stress, postoperative pain, and related complications directly affect the smooth progression and outcome of surgery. Patients may experience a series of psychological and physiological changes during the perioperative period, resulting in anxiety and depression, which may reduce the pain threshold and worsen their prognosis.

To investigate the effects of a psychological intervention among perioperative patients, based on social cognitive theory (SCT).

We enrolled 200 patients who underwent surgical care at The First People’s Hospital of Lin’an District, Hangzhou between January and December 2023. They were categorized into a routine intervention group (n = 103) and a psychological intervention group (n = 97), based on the intervention strategies used. Various assessment tools, including the self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), the self-rating depression scale (SDS), and the Connor–Davidson Resilience scale, were used to measure patients’ negative states and emotions. The pre- and post-intervention scores for these metrics in the two groups were then analyzed.

In the psychological intervention group, the SAS and SDS scores (31.56 ± 5.18 and 31.46 ± 4.57, respectively) were significantly reduced compared to the routine intervention group (P < 0.05). The visual analog scale pain scores at 12 and 24 hours after intervention (6.85 ± 1.21, 4.24 ± 0.72) were notably higher than those in the routine intervention group (P < 0.05). The psychological intervention group also demonstrated superior scores in perseverance (36.08 ± 3.29), self-reliance (22.63 ± 2.91), optimism (11.42 ± 1.98), and resilience (70.13 ± 5.37), compared to the routine intervention group (P < 0.05). Additionally, the psychological intervention group’s confrontation score (23.16 ± 4.29) was higher (P < 0.05). This group also reported lower scores in avoidance (9.28 ± 1.94) and yielding (6.19 ± 1.92) (P < 0.05). Lastly, the Short Form 36 Health Survey scores were significantly higher in the psychological intervention group, indicating a better quality of life (P < 0.05).

Psychological intervention measures based on SCT can effectively alleviate pain, anxiety, and depression in perioperative patients.

Core Tip: Patients may experience a series of psychological and physiological changes during the perioperative period, resulting in anxiety and depression, which could reduce pain threshold and worsen their prognosis. Using social cognitive theory, we developed psychological intervention measures to explore their effectiveness in reducing pain, anxiety, and depression in perioperative patients.

- Citation: Mao HJ, Wang LF, Lin C. Psychological intervention based on social cognitive theory: Treating pain, anxiety, and depression in perioperative patients. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(8): 1199-1207

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i8/1199.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i8.1199

Surgery is an effective method for treating certain diseases. However, factors such as preoperative fear and tension, surgical stress, postoperative pain, and related complications directly influence the smooth progression and outcome of surgery. The perioperative period (also known as the entire operative period) covers the preoperative and postoperative phases of medical treatment. At this stage, patients may experience a series of psychological and physiological changes[1,2]. Perioperative nursing is an auxiliary method used before, during, and after treatment. Reasonable psychological intervention could assuage negative emotions in patients, make their pain less intense, and improve their quality of life (QoL), so that they can face treatment with an improved attitude and experience a certain positive effect on their prognosis[3]. Social cognitive theory (SCT) is an essential starting point, while individual behavior, individual cognition, and an individual’s objective environment can also impact human activity; moreover, there are connotations among these factors. Cognitive factors, such as people’s beliefs, motives, memories, and self-reinforcement, guide and dominate behavior; behavioral outcomes are fed back to people who react to this content and structure of their thinking, as well as their own emotions[4]. In recent years, with the promotion and implementation of high-quality nursing in major hospitals, research has come to frequently explore new nursing models to improve patient outcomes and boost nursing quality. Therefore, this study uses SCT to develop psychological intervention measures and to explore their effectiveness in reducing pain, anxiety, and depression in perioperative patients.

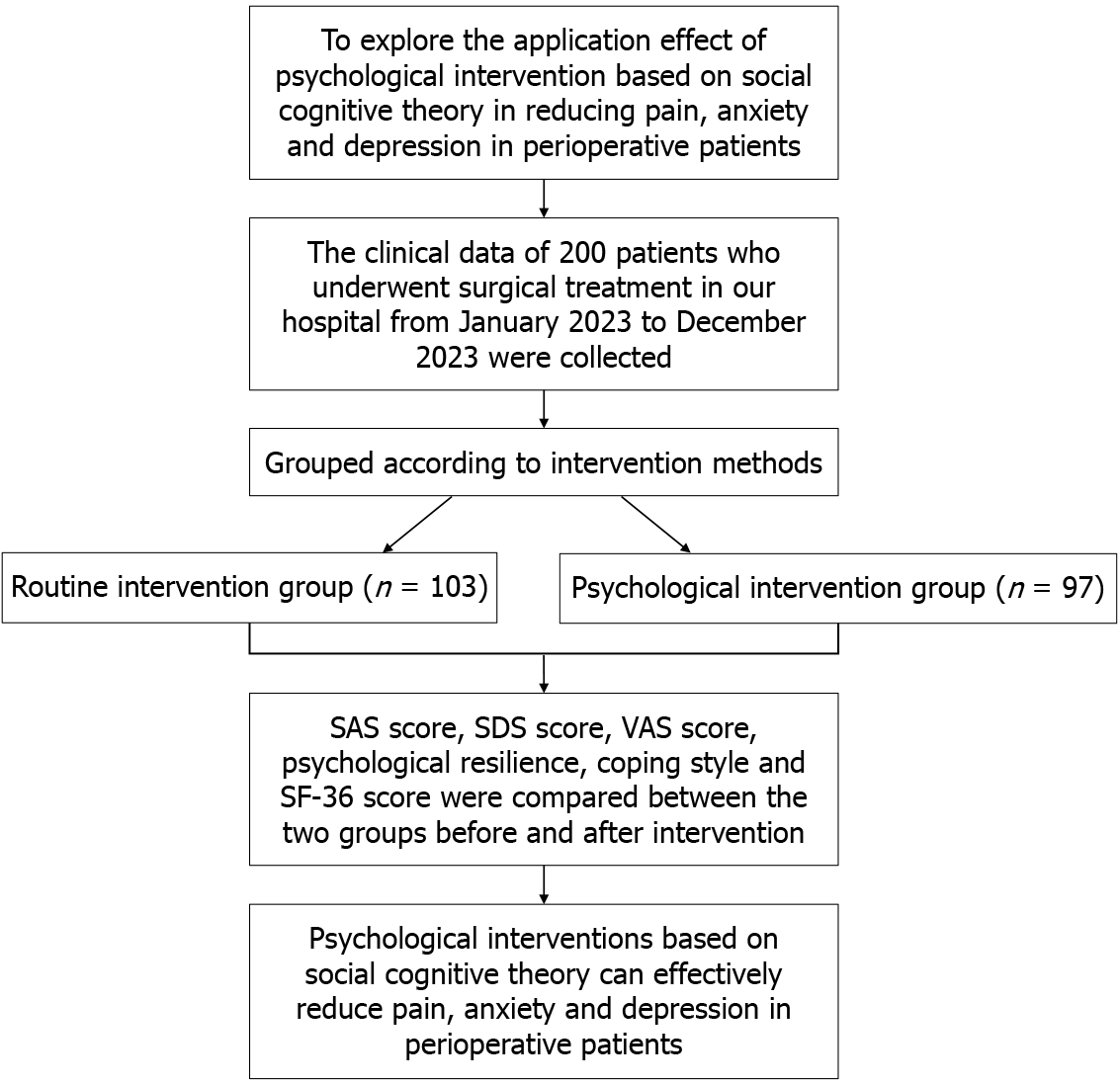

We analyzed the medical records of 200 individuals who underwent surgical procedures at The First People’s Hospital of Lin’an District, Hangzhou between January and December 2023. We categorized these cases into two groups, based on the intervention techniques used: A routine intervention group (n = 103) and a psychological intervention group (n = 97), as depicted in Figure 1. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Participants must have full medical records available; and (2) they must be aged 18 to 75 years old. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Individuals with a documented psychiatric disorder; (2) patients who had severe perioperative complications and discontinued treatment; (3) patients receiving radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy; (4) patients suffering from critical conditions of blood vessels in the heart and brain, as well as those with advanced liver, kidney, or blood-forming system disorders; and (5) patients with malignant tumors, chronic inflammation, or autoimmune disease.

Patients in the routine intervention group received standard care, which included individual oral education, daily clinical care, and ward management.

Based on routine intervention, patients in the psychological intervention group received measures based on SCT. These interventions were as follows: (1) During the perioperative period, patients were provided with comprehensive information about the surgery, including the procedures involved, the anticipated outcomes, and potential risks. This approach aimed to foster accurate expectations about the surgery and recovery process among the patients, thereby mitigating feelings of anxiety and fear; (2) Patients were also directed to manage their stress effectively; this included recalling the details of conversations within themselves or outside in their daily work and life, reassessing their roles, embracing their negative thoughts, and seeking appropriate outlets for expression. When self-resolution was not feasible or effective, psychological counseling and emotional support were offered temporarily, to help patients manage their negative emotions. Researchers stressed that the most important thing for patients was to cultivate the ability to resolve their own emotions; (3) Patients’ families and friends were encouraged to offer emotional support and practical assistance during the perioperative period. The presence of loved ones was intended to alleviate anxiety and possible feelings of isolation. Additionally, support networks were established, encompassing family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and community support groups; and (4) Healthcare professionals provided patients with comprehensive guidance regarding postoperative care, including activity schedules, pain management, and medication administration. Positive reinforcement in the form of praise and encouragement was given when patients adhered to the recommended practices; these actions were intended to bolster their self-confidence in their recovery capabilities and increase their engagement in rehabilitation activities.

We searched for patient data in the hospital’s electronic medical records system. We adopted a double-check system with two people and dual-core processors to avoid errors during data extraction: (1) We collected clinical baseline data including sex, age, place of residence, marital status, education level, occupation, medical security form, and family monthly income; (2) We used the self-rating anxiety scale[5] and the self-rating depression scale[6] to evaluate subjective feelings of anxiety and depression. Each scale comprises 20 items that are scored on a scale of 1 to 4 points. We deter

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical data were presented as frequencies (n) and percentages (%), and group comparisons were made using the χ2 test. Continuous data were reported as the mean ± SD, with group comparisons conducted using the t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

We compared the general data between the routine and psychological intervention groups. There were 77 males (74.76%) and 26 females (25.24%) in the routine intervention group, with ages ranging from 18 years to 66 years. The psychological intervention group included 69 males (71.13%) and 28 females (28.87%), with ages ranging from 19 years to 74 years (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Feature | Routine intervention group, n = 103 | Psychological intervention group, n = 97 | χ2/t | P value |

| Sex | 0.333 | 0.564 | ||

| Male | 77 (74.76) | 69 (71.13) | ||

| Female | 26 (25.24) | 28 (28.87) | ||

| Age in years | 40.88 ± 12.46 | 41.48 ± 11.37 | -0.436 | 0.664 |

| Place of residence | 0.559 | 0.455 | ||

| City | 72 (69.90) | 63 (64.95) | ||

| Village or town | 31 (30.10) | 34 (35.05) | ||

| Marital status | 2.726 | 0.436 | ||

| Married | 52 (50.49) | 42 (43.30) | ||

| Single | 27 (26.21) | 32 (32.99) | ||

| Divorced | 15 (14.56) | 18 (18.56) | ||

| Widowed | 9 (8.74) | 5 (5.15) | ||

| Education level | 0.864 | 0.834 | ||

| Primary and below | 17 (16.50) | 20(20.62) | ||

| Junior high school | 29 (28.16) | 29 (29.90) | ||

| High school or technical secondary school | 33 (32.04) | 27 (27.83) | ||

| Junior college or above | 24 (23.30) | 21 (21.65) | ||

| Occupation | 1.606 | 0.658 | ||

| On the job | 56 (54.37) | 46 (47.42) | ||

| Take leave or retire | 11 (10.68) | 10 (10.31) | ||

| Individual or farmer | 22 (21.36) | 28 (28.87) | ||

| Unemployed | 14 (13.59) | 13 (13.40) | ||

| Form of medical security | 0.589 | 0.443 | ||

| Worker with medical insurance | 67 (65.05) | 58 (59.79) | ||

| Medical insurance for residents | 36 (34.95) | 39 (40.21) | ||

| Monthly household income | 1.705 | 0.426 | ||

| < 5000 | 60 (58.25) | 64 (65.98) | ||

| 5000-8000 | 31 (30.10) | 26 (26.80) | ||

| > 8000 | 12 (11.65) | 7 (7.22) |

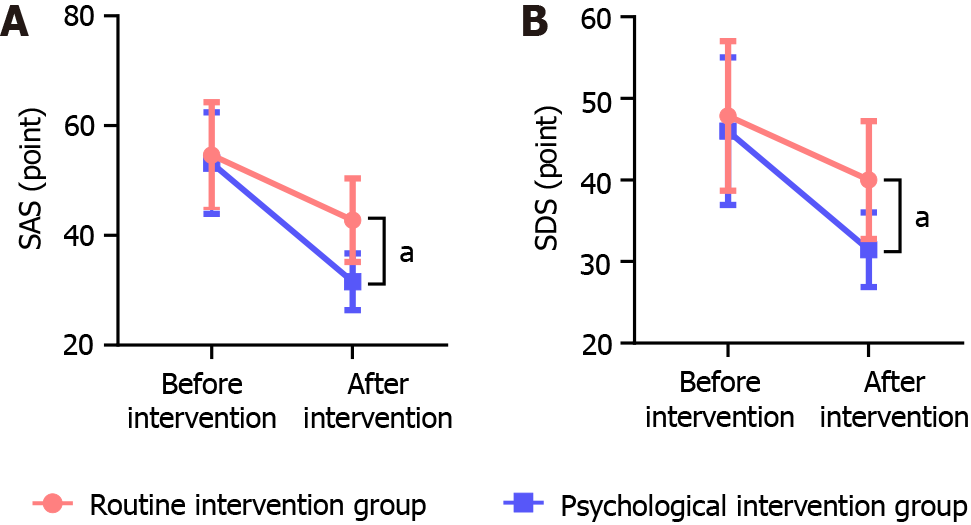

Before the intervention, the patients had similar anxiety and depression statuses (P > 0.05). Although both intervention models had some impact on patients, the psychological intervention based on SCT had a more significant inhibitory effect on anxiety and depression (P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

Before any intervention, the total scores for perseverance, self-reliance, optimism, and resilience showed no significant differences among all patients (P > 0.05). Both intervention models had some impact on the patients; however, the total scores for perseverance, self-reliance, optimism, and resilience were higher in the psychological intervention group, indicating poorer outcomes in the routine intervention group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Group | Perseverance | Self-reliance | Optimism | Total |

| Before the intervention | ||||

| Routine intervention group | 23.95 ± 3.06 | 10.69 ± 3.19 | 4.60 ± 1.39 | 39.24 ± 4.40 |

| Psychological intervention group | 23.57 ± 3.18 | 10.14 ± 3.42 | 4.53 ± 1.36 | 38.24 ± 4.97 |

| t value | 0.861 | 1.177 | 0.360 | 1.509 |

| P value | 0.390 | 0.241 | 0.719 | 0.133 |

| After intervention | ||||

| Routine intervention group | 29.18 ± 4.61 | 15.86 ± 3.03 | 8.81 ± 1.85 | 53.85 ± 5.37 |

| Psychological intervention group | 36.08 ± 3.29 | 22.63 ± 2.91 | 11.42 ± 1.98 | 70.13 ± 5.37 |

| t value | 12.118 | 16.098 | 9.637 | 21.427 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

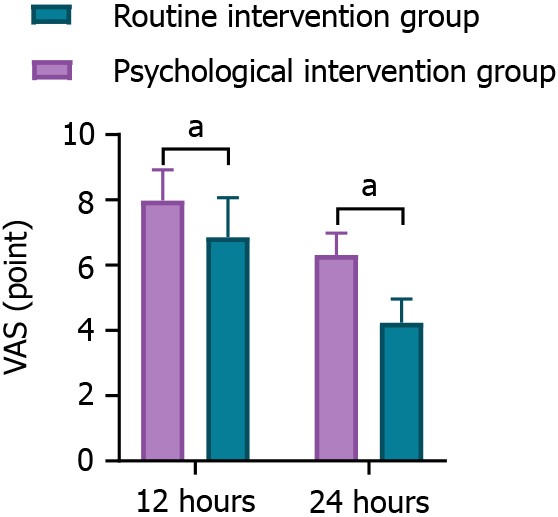

We recorded the patients’ VAS scores 12 and 24 hours after the intervention. Compared to the routine intervention group, the VAS scores of patients who received the psychological intervention based on SCT were significantly lower (P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

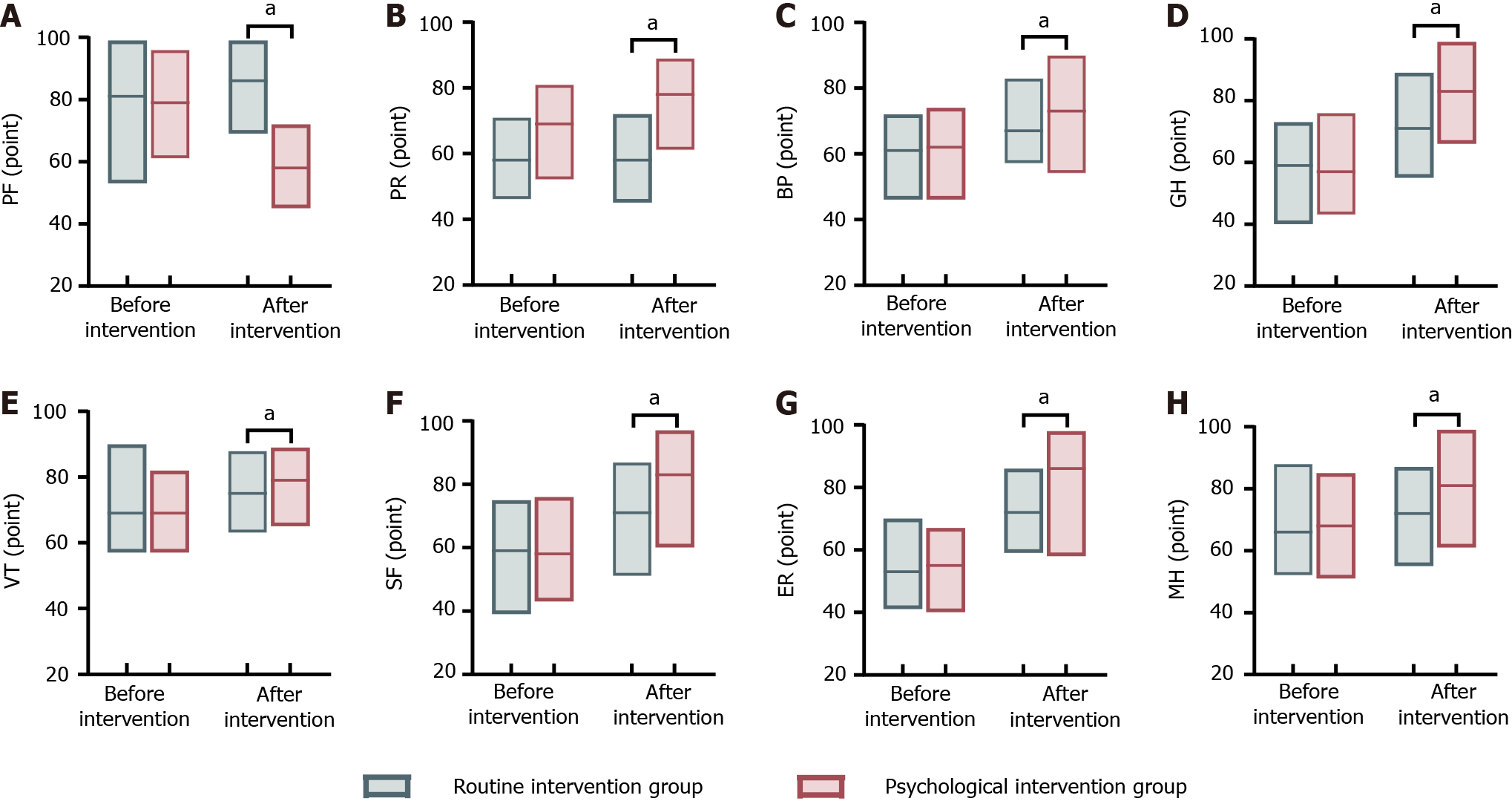

Before any intervention, the SF-36 scale scores did not show significant disparity (P > 0.05). The results indicated that perioperative patients who received psychological intervention based on SCT had higher SF-36 scores, suggesting a better QoL for this group (P < 0.05) (Figure 4).

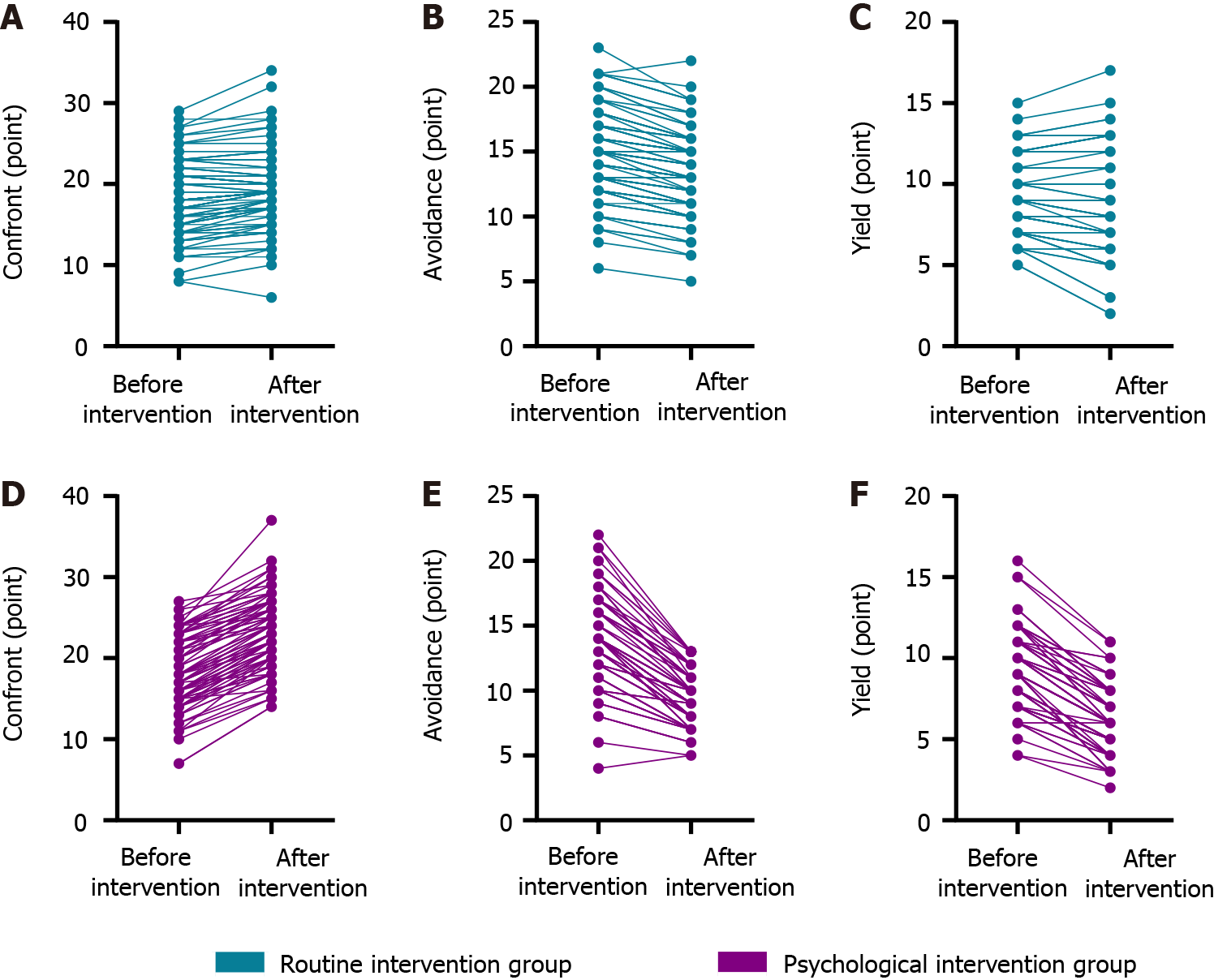

Without any intervention, the scores for confrontation, avoidance, and yielding among all patients demonstrated no significant differences (P > 0.05). After the psychological intervention, the confrontation score increased, while the avoidance and yielding scores decreased (P < 0.05). However, there was no significant change in the routine intervention group (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Surgery is an effective means of treating disease; however, it is also a stressor. Patients experience disease-related stress after illness. During the perioperative period, patients are prone to fear, anxiety, depression, and other emotions due to factors such as the environment, disease, surgery, and prognosis, which increase their pain sensitivity and are not conducive to the implementation of surgery and postoperative rehabilitation[11]. The traditional nursing model is disease-centered, and nursing measures do not involve initiatives, which makes it difficult to alleviate the negative emotional environment that patients encounter before surgery and to facilitate rapid recovery afterward. In recent years, with the implementation and development of high-quality nursing in China, research hotspots include exploring new nursing models and improving the quality of nursing. SCT is a learning theory proposed by Albert Bandura, a well-known American psychologist[12]. This concept posits that learning occurs by observing others’ actions, outcomes, and environmental influences, which shape one’s behavior, beliefs, and attitudes. This theory highlights the dynamic interplay between an individual’s actions, personal characteristics, and environmental elements. The current study employs various questionnaires to assess patients undergoing treatment across multiple dimensions, including psychological state, pain perception, and coping mechanisms. The goal was to gain a holistic understanding of how psychological interventions informed by SCT can effectively alleviate the pain, anxiety, and depression experienced by patients during the perioperative period.

This study indicates that after the psychological intervention based on SCT, perioperative patients who had experienced anxiety and depression showed increased perseverance, self-reliance, optimism, and psychological resilience. This implies that the psychological intervention model has significant value in improving the psychological state and resilience of perioperative patients. Due to a shortage of relevant surgical knowledge, patients often have serious concerns about the surgical method, safety, and postoperative rehabilitation effect. These concerns can aggravate depression, anxiety, and other adverse psychological conditions, resulting in reduced immune function and poor treatment compliance, which is not conducive to postoperative rehabilitation[13-15]. Psychological support based on SCT focuses on eliminating patients’ negative psychological emotions such as tension and fear. Through education that promotes knowledge regarding health, benign communication, limb relaxation, music, and other methods, patients’ poor cognition can be corrected, and their negative psychology and emotions can be alleviated, enabling them to better cooperate with the treatment process and facilitate postoperative rehabilitation.

Resilience is an individual’s ability to adapt and successfully cope with adversity[16,17]. Perioperative patients generally experience great psychological pressure; they often have negative emotions such as pessimism and dis

After the psychological intervention, perioperative patients experienced a significant reduction in pain and notable improvements in each dimension of the SF-36, suggesting that this intervention mode is effective and feasible for reducing patients’ pain and improving their QoL. Perioperative pain is a complex physiological and psychological reaction caused by noxious stimulation of the body. This can lead to poor immune function in patients, reduce the effectiveness of follow-up treatment effect, and prolong hospitalization through the interactions of the psychological-neuro-immune system. Thus, it is necessary to implement appropriate interventions.

Pain can arise due to a primary disease, punctures during surgery, inflammatory reactions to catheter-related operations, and other factors; it can induce delirium, agitation, convulsions, and other symptoms and is not conducive to patients’ recovery and prognosis[18]. Drawing from the framework of SCT, healthcare providers can equip patients with insights into the nature of their pain, available treatments, and self-care techniques. This education aims to enhance patients’ understanding of their condition and thereby alleviate their apprehension and doubts. Recognizing that emotional well-being can influence pain perception, psychological support can assist patients in more effectively regulating their emotions, which can subsequently have a positive impact on their experience of pain. Furthermore, such interventions may reduce the incidence of typical postoperative complications and potentially shorten hospital stays. Mental health is closely correlated with QoL. By encouraging family members to communicate with patients, their sense of support increases, and their strong sense of dependence is adapted. Through psychological counseling, a patient’s negative mood can be alleviated, and their self-concept and role adaptation can be enhanced. This effectively reduces the inherent stimulation source and improves QoL. Hence, it is necessary to strengthen psychological interventions during the perioperative period[19,20].

Patients requiring surgery are usually psychologically fragile, and surgical treatment adversely affects both the mind and body. Patients are prone to somatic symptoms and negative emotions. Without timely intervention, they are likely to develop more serious anxiety disorders and depression, which can affect postoperative recovery. Patients with severe depression may have suicidal thoughts that threaten their lives[21-23]. We found that after the psychological intervention, perioperative patients’ confrontation scores increased while their avoidance and yielding scores decreased. This implies that the psychological intervention based on SCT positively influenced their psychological coping styles. Using SCT, medical personnel can guide patients to acquire accurate knowledge of their health, maintain a positive attitude, and deepen their belief in disease treatment and family support so that they can take positive steps according to the established rehabilitation plan, achieve their expected goals, and improve their prognosis[24]. The psychological intervention helps patients avoid yielding and avoidance behaviors, improves their subjective initiative, and maximizes their ability to participate in rehabilitation, effectively promoting limb rehabilitation. Psychological coping styles are closely associated with mental health; positive coping styles can reduce anxiety and depression and promote mental well-being.

In summary, psychological intervention measures based on SCT have a clear concept, strong logic, and compact and reasonable processes. When combined with actual nursing work, they form a systematic and independent process and framework that helps alleviate patients’ anxiety and depression and reduces pain. Our results confirm that psychological intervention measures based on SCT can help to control the various sources of stress impacting patients during the perioperative period through nursing measures, thereby improving psychological resilience and QoL, alleviating anxiety and depression, and reducing patients’ pain.

However, our study faced several constraints. It was a single-center retrospective study with a sample from only one hospital, leading to limitations in the selection of cases. In future studies, we will include multiple institutions in our research and select sufficiently large samples to provide a more reliable basis for psychological intervention based on SCT.

| 1. | Eberhart L, Aust H, Schuster M, Sturm T, Gehling M, Euteneuer F, Rüsch D. Preoperative anxiety in adults - a cross-sectional study on specific fears and risk factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Madsen BK, Zetner D, Møller AM, Rosenberg J. Melatonin for preoperative and postoperative anxiety in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12:CD009861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abraham J, Holzer KJ, Lenard EM, Meng A, Pennington BRT, Wolfe RC, Haroutounian S, Calfee R, Hammil CW, Kozower BD, Cordner TA, Schweiger J, McKinnon S, Yingling M, Baumann AA, Politi MC, Kannampallil T, Miller JP, Avidan MS, Lenze EJ. A Perioperative Mental Health Intervention for Depressed and Anxious Older Surgical Patients: Results From a Feasibility Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2024;32:205-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Anton S, Das SK, McLaren C, Roberts SB. Application of social cognitive theory in weight management: Time for a biological component? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:1982-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2251] [Cited by in RCA: 2947] [Article Influence: 53.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5900] [Cited by in RCA: 6297] [Article Influence: 209.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhao XF, Zhao YB, Lu XD, Qi DT, Yang X, Wang WX, Wang XN, Zhou RT, Jin YZ, Zhao B. Development and Clinical Application of a New Open-Powered Nail Anterior Cervical Plate System. Orthop Surg. 2020;12:248-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4591] [Cited by in RCA: 5647] [Article Influence: 256.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao L, Sznajder K, Cheng D, Wang S, Cui C, Yang X. Coping Styles for Mediating the Effect of Resilience on Depression Among Medical Students in Web-Based Classes During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Questionnaire Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e25259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sanders J, Bowden T, Woolfe-Loftus N, Sekhon M, Aitken LM. Predictors of health-related quality of life after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20:79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Srifuengfung M, Abraham J, Avidan MS, Lenze EJ. Perioperative Anxiety and Depression in Older Adults: Epidemiology and Treatment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;31:996-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3758] [Cited by in RCA: 4060] [Article Influence: 184.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jung MJ, Libaw JS, Ma K, Whitlock EL, Feiner JR, Sinskey JL. Pediatric Distraction on Induction of Anesthesia With Virtual Reality and Perioperative Anxiolysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:798-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Faruqi F, Ruddy KJ, Blackmon S. Integrative Approaches to Minimize Peri-operative Symptoms. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu M, Dai S, Wang R, Yang S. The relationship between uncertainty and acute procedure anxiety among surgical patients in Chinese mainland: the mediating role of resilience. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lim KK, Matchar DB, Tan CS, Yeo W, Østbye T, Howe TS, Koh JSB. The Association Between Psychological Resilience and Physical Function Among Older Adults With Hip Fracture Surgery. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:260-266.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alarcón R, Cerezo MV, Hevilla S, Blanca MJ. Psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in women with breast cancer. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2020;20:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kalfon P, Boucekine M, Estagnasie P, Geantot MA, Berric A, Simon G, Floccard B, Signouret T, Fromentin M, Nyunga M, Audibert J, Ben Salah A, Mauchien B, Sossou A, Venot M, Robert R, Follin A, Renault A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Collange O, Levrat Q, Villard I, Thevenin D, Pottecher J, Patrigeon RG, Revel N, Vigne C, Azoulay E, Mimoz O, Auquier P, Baumstarck K; IPREA Study Group. Risk factors and events in the adult intensive care unit associated with pain as self-reported at the end of the intensive care unit stay. Crit Care. 2020;24:685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rousseaux F, Dardenne N, Massion PB, Ledoux D, Bicego A, Donneau AF, Faymonville ME, Nyssen AS, Vanhaudenhuyse A. Virtual reality and hypnosis for anxiety and pain management in intensive care units: A prospective randomised trial among cardiac surgery patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2022;39:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Monteiro JLGC, da Silva Barbirato D, Moraes SLD, Pellizzer EP, do Egito Vasconcelos BC. Does listening to music reduce anxiety and pain in third molar surgery?-a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26:6079-6086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kassahun WT, Mehdorn M, Wagner TC, Babel J, Danker H, Gockel I. The effect of preoperative patient-reported anxiety on morbidity and mortality outcomes in patients undergoing major general surgery. Sci Rep. 2022;12:6312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tigges-Limmer K, Sitzer M, Gummert J. Perioperative Psychological Interventions in Heart Surgery-Opportunities and Clinical Benefit. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li XR, Zhang WH, Williams JP, Li T, Yuan JH, Du Y, Liu JD, Wu Z, Xiao ZY, Zhang R, Liu GK, Zheng GR, Zhang DY, Ma H, Guo QL, An JX. A multicenter survey of perioperative anxiety in China: Pre- and postoperative associations. J Psychosom Res. 2021;147:110528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Salzmann S, Euteneuer F, Kampmann S, Rienmüller S, Rüsch D. Preoperative anxiety and need for support - A qualitative analysis in 1000 patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2023;115:107864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: Https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/