Published online Jun 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i6.812

Revised: April 13, 2024

Accepted: April 25, 2024

Published online: June 19, 2024

Processing time: 120 Days and 6.4 Hours

Psychological problems are becoming increasingly prominent among older patients with leukemia, with patients potentially facing stigmatization after diagnosis. However, there is limited research on the stigma experienced by these patients and the factors that may contribute to it.

To investigate the stigma faced by older patients after being diagnosed with leu

A retrospective analysis was conducted using clinical data obtained from questionnaire surveys, interviews, and the medical records of older patients with leukemia admitted to the Hengyang Medical School from June 2020 to June 2023. The data obtained included participants’ basic demographic information, medical history, leukemia type, family history of leukemia, average monthly family income, pension, and tendency to conceal illness. The Chinese versions of the Social Impact Scale (SIS), Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) were used to assess indicators related to stigma, social support, and mental health status. We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to analyze the strength and direction of the relationship between the scores of each scale, and regression analysis to explore the factors related to the stigma of older patients with leukemia after diagnosis.

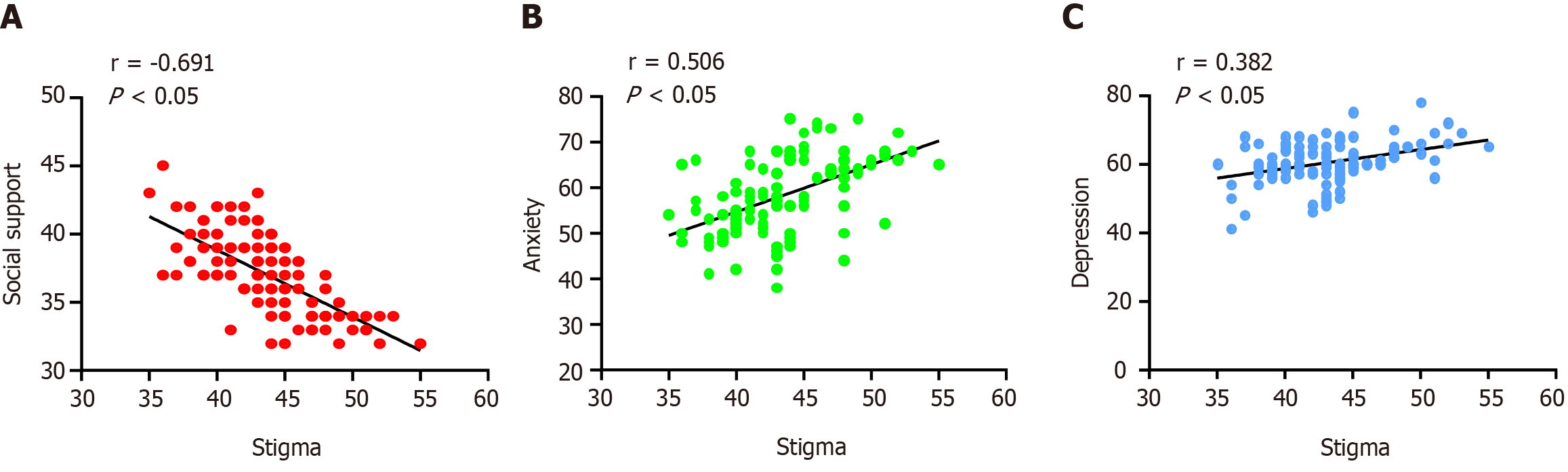

Data from 120 patients with leukemia aged 65-80 years were analyzed. The total score on the SIS and PSSS was 43.60 ± 4.07 and 37.06 ± 2.87, respectively. The SAS score was 58.35 ± 8.32 and the SDS score was 60.58 ± 5.97. The stigma experienced by older leukemia patients was negatively correlated with social support (r = -0.691, P < 0.05) and positively correlated with anxiety and depression (r = 0.506, 0.382, P < 0.05). Age, education level, smoking status, average monthly family income, pension, and tendency to conceal illness were significantly associated with the participants’ level of stigma (P < 0.05). Age, smoking status, social support, anxiety, and depression were predictive factors of stigmatization among older leukemia patients after diagnosis (all P < 0.05), with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.644 and an adjusted R2 of 0.607.

Older patients commonly experience stigmatization after being diagnosed with leukemia. Factors such as age, smoking status, social support, and psychological well-being may influence older patients’ reported experience of stigma.

Core Tip: The most innovative and important finding of this study is that older patients with leukemia commonly experience feelings of stigmatization after diagnosis, which are influenced by factors such as age, smoking status, social support, and psychological status. This study highlights the importance of addressing the psychological well-being and social support that older patients with leukemia receive to mitigate feelings of stigmatization and to improve their overall quality of life.

- Citation: Tang X, Chen SQ, Huang JH, Deng CF, Zou JQ, Zuo J. Assessing the current situation and the influencing factors affecting perceived stigma among older patients after leukemia diagnosis. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(6): 812-821

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i6/812.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i6.812

The data obtained for this study show that the incidence rate of leukemia in China is currently 6.21 per 100000, with a mortality rate of 4.03 per 100000[1]. The age of China’s population is increasing, with over 267 million Chinese citizens currently aged 60 and above. The number of older patients with acute leukemia is also increasing annually[2], making them the core demographic among adults diagnosed with acute leukemia. A leukemia diagnosis is a major blow to patients. Leukemia not only affects patients’ physical health, but it can also cause psychological and social problems. Among the range of potential side effects that follow a leukemia diagnosis, stigma is a common psychological reaction. Stigma refers to the embarrassment or self-doubt that patients often experience in relation to their illness[3,4]. It is a complex issue involving multiple disciplines, including medicine, sociology, and psychology, and has received increasing attention from researchers in recent years.

Extensive research has been conducted into the stigma that occurs around certain diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and mental illnesses. In a study by Vrbova et al[5], patients with stable schizophrenia revealed a tendency to choose suicide as a means of escaping the psychological problems they faced, with the increased stigma caused by the illness putting them at greater risk of committing suicide. Clement et al[6] conducted a systematic review of 144 studies on stigma among mental health patients. Their findings revealed the mild-to-moderate impact of stigma on patients’ likelihood of seeking help, with disclosure of the problem being the most common stigma barrier. Nikus Fido et al[7] found that HIV/AIDS patients commonly experience stigma, with educational level and gender being closely related to stigma, and social support being an important influencing factor. Studies have found that stigma can lead to a delay in seeking medical treatment, concealment of disease information, avoidance of social activities, and reduced treatment adherence, thereby affecting patients' recovery and quality of life[8,9]. Stigma can cause older patients with leukemia to experience self-denial, confusion, and helplessness. It can also lead to self-isolation and avoidance of interactions with the outside world, depriving patients of opportunities to connect with family, friends, and other patients with similar experiences, further increasing their emotional burden. These emotional issues can also impact patients' immune systems, making them more susceptible to infection and making their recovery more difficult, thus creating a vicious cycle.

Psychological problems among older patients with leukemia are becoming increasingly prominent. However, limited research has been conducted on the role that stigma plays with regard to these issues. Understanding and recognizing whether older patients experience stigma after being diagnosed with leukemia and conducting in-depth research on the factors that influence stigma can help facilitate the development of more effective methods and strategies. These strategies can in turn help to alleviate the symptoms associated with stigma and enable patients to cope more easily, allowing for more comprehensive support and assistance to be provided to them.

The dataset for this retrospective analysis was derived from clinical data, such as questionnaires, interviews, and medical records filled in by older patients with leukemia admitted to the Hengyang Medical School, University of South China from June 2020 to June 2023. To ensure the consistency and comparability of the subjects, it was necessary to develop inclusion criteria through which to screen patients and determine if they met the requirements of the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients had been diagnosed with leukemia for the first time and were over 65 years of age, regardless of sex, race, or disease type; and (2) patients were willing to participate in the study and capable of providing informed consent. Patients who did not fit the study’s criteria, or whose condition may have interfered with the results of the study, such as patients with cognitive impairment or severe mental illness, patients with other major diseases or complications, or patients who could not provide valid data were all excluded from participating.

Demographic factors relating to age, sex, marital status, education level, smoking and drinking status, underlying medical history, average monthly family income, retirement pension, type of leukemia, family history of leukemia, and tendency to conceal disease were obtained from the questionnaire survey records. Patients’ reported levels of stigma, social support, and psychological well-being were assessed using Chinese versions of the Social Impact Scale (SIS), Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS). The dimensions and scoring methods of these scales are as follows: (1) The SIS consists of 18 items and three dimensions (social rejection, social isolation, and internal stigma). A 4-point Likert scale was used for each item, with responses ranging from "1-strongly disagree" to "4-agree." The total score ranged from 18-72 points, with higher scores indicating a higher level of stigma experienced by patients; (2) the PSSS consists of 12 items and three dimensions (family, friends, and other support). A 7-point Likert scale was used for each item, with responses ranging from "1-strongly disagree" to "7-agree." The total score ranged from 12-84 points, with higher scores indicating better perceived support; and (3) the SAS and SDS each contained 20 questions covering psychological and physiological symptoms of anxiety and depression, such as tension, fear, and worry. A 4-point Likert scale was used for each question, with responses ranging from "1-none or rarely" to "4-frequently or almost always". The total score ranged from 20-80 points, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety and depression symptoms.

To minimize the impact of missing data on the results, the following methods were adopted: (1) During data collection, the collected data were carefully examined to ensure optimal data integrity and accuracy; (2) the reasons for any missing data, such as questionnaire errors or losses, were carefully analyzed to ensure that appropriate measures were taken; and (3) for partially missing data, imputation methods such as mean and multiple imputations were employed to handle data filling.

The means and standard deviations were calculated to describe the average scores for each scale. Percentages or frequencies were used to determine the proportion or frequency of individuals with different score ranges. Significant differences in scores between different groups (e.g., sex and age groups) were compared using the t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple comparisons were made using the Fisher's least significant difference test. The relationship between the scale scores and other variables was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation. A regression analysis was then conducted to predict the relationship between the scale scores and independent variables. All analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0, with a significance level of α = 0.05.

After the screening was completed, 120 patients aged 65-80 years were enrolled. The majority of the patients had been diagnosed with acute leukemia, of whom 89 (74.2%) reported having no family history of leukemia. The patients’ education level was roughly balanced: 33 patients (27.50%) had a junior high school level education or below, 44 patients (36.67%) had a senior high school/technical secondary school level education, and 43 patients (35.83%) had a college level education or above. In terms of bad habits, 42 patients (35%) smoked and 69 (57.50%) consumed alcohol. The proportion of patients with a per capita monthly family income of 3000-5000 yuan was the largest, accounting for 49 cases (40.83%), while more than half of the patients reported having no pension (Table 1).

| Items | Groups | Frequency | % |

| Age (yr) | 65-75 | 50 | 41.7 |

| > 75 | 70 | 58.3 | |

| Sex | Male | 53 | 44.2 |

| Female | 67 | 55.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 6 | 5.0 |

| Married | 89 | 74.2 | |

| Divorced/widowed | 25 | 20.8 | |

| Education level | Junior high school and below | 33 | 27.5 |

| High school or technical secondary school | 44 | 36.7 | |

| College or above | 43 | 35.8 | |

| Smoking | No | 78 | 65.0 |

| Yes | 42 | 35.0 | |

| Drinking | No | 51 | 42.5 |

| Yes | 69 | 57.5 | |

| Medical history | No | 62 | 51.7 |

| Yes | 58 | 48.3 | |

| Average monthly family income (CNY) | < 3000 | 29 | 24.2 |

| 3000-5000 | 49 | 40.8 | |

| > 5000 | 42 | 35.0 | |

| Pension | No | 67 | 55.8 |

| Yes | 53 | 44.2 | |

| Leukemia type | Chronic | 34 | 28.3 |

| Acute | 86 | 71.7 | |

| Family history | No | 89 | 74.2 |

| Yes | 31 | 25.8 | |

| Tendency to conceal illness | No | 47 | 39.2 |

| Yes | 73 | 60.8 |

The score for the social exclusion dimension was 13.82 ± 2.41; the score for the social isolation dimension was 7.32 ± 1.33; the score for the internal stigma dimension was 22.47 ± 2.97, and the SIS-total score was 43.60 ± 4.07. These results suggest that patients may face exclusion and isolation from society and may internalize a strong sense of stigma in relation to the disease (Table 2).

| Scale | Item | Score range | Score |

| Social exclusion dimension | 7 | 7-28 | 13.82 ± 2.41 |

| Social isolation dimension | 3 | 3-12 | 7.32 ± 1.33 |

| Internal shame dimension | 8 | 8-32 | 22.47 ± 2.97 |

| SIS-total | 18 | 18-72 | 43.60 ± 4.07 |

The score for the family support dimension was 14.23 ± 1.83; the score for the friend support dimension was 12.05 ± 1.53; the score for the other support dimension was 10.78 ± 1.91; and the PSSS-total score was 37.06 ± 2.87. The SAS score was 58.35 ± 8.32 points, and the SDS score was 60.58 ± 5.97 points. These results suggest that older patients with leukemia experience a moderate level of support from family, friends, and others, and that the overall level of social support they receive is relatively low. However, the scores corresponding to anxiety and depression in the patients’ self-evaluation were also higher, meaning further attention and intervention are needed (Table 3).

| Scale | Item | Score range | Score |

| Family support dimension | 4 | 4-28 | 14.23 ± 1.83 |

| Friend support dimension | 4 | 4-28 | 12.05 ± 1.53 |

| Other support dimension | 4 | 4-28 | 10.78 ± 1.91 |

| PSSS-total | 12 | 12-84 | 37.06 ± 2.87 |

| SAS-total | 20 | 20-80 | 58.35 ± 8.32 |

| SDS-total | 20 | 20-80 | 60.58 ± 5.97 |

The classification of different demographic and disease-related data variables were used as independent variables, and stigma was used as the dependent variable for a single-factor analysis. There were statistically significant differences in patients’ age, education level, smoking status, family monthly income per capita, pension, and disease concealment tendency (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Variable | n | SIS-total | t/F | P value |

| Age (a) | -4.006 | < 0.05 | ||

| 65-75 | 50 | 41.94 ± 3.61 | ||

| > 75 | 70 | 44.79 ± 3.99 | ||

| Sex | -1.030 | 0.305 | ||

| Male | 53 | 43.17 ± 3.78 | ||

| Female | 67 | 43.94 ± 4.29 | ||

| Marital status | 1.053 | 0.352 | ||

| Single | 6 | 42.00 ± 3.90 | ||

| Married | 89 | 43.90 ± 4.28 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 25 | 42.92 ± 3.23 | ||

| Education level | 4.231 | 0.0171 | ||

| Junior high school and below | 33 | 42.37 ± 3.27 | ||

| High school or technical secondary school | 44 | 43.73 ± 3.94 | ||

| College or above | 43 | 45.03 ± 4.75 | ||

| Smoking | -3.865 | < 0.05 | ||

| No | 78 | 42.60 ± 3.81 | ||

| Yes | 42 | 45.45 ± 3.93 | ||

| Drinking | -1.393 | 0.166 | ||

| No | 51 | 43.00 ± 3.82 | ||

| Yes | 69 | 44.04 ± 4.22 | ||

| Medical history | 0.259 | 0.796 | ||

| No | 62 | 43.69 ± 4.40 | ||

| Yes | 58 | 43.50 ± 3.72 | ||

| Average monthly family income (CNY) | 4.522 | 0.0131 | ||

| < 3000 | 29 | 42.48 ± 3.81 | ||

| 3000-5000 | 49 | 43.53 ± 3.72 | ||

| > 5000 | 42 | 45.34 ± 4.51 | ||

| Pension | 3.176 | 0.002 | ||

| No | 67 | 44.61 ± 4.25 | ||

| Yes | 53 | 42.32 ± 3.47 | ||

| Leukemia type | 0.675 | 0.501 | ||

| Chronic | 34 | 44.00 ± 3.87 | ||

| Acute | 86 | 43.44 ± 4.16 | ||

| Family history | 0.286 | 0.776 | ||

| No | 89 | 43.66 ± 4.23 | ||

| Yes | 31 | 43.42 ± 3.64 | ||

| Tendency to conceal illness | -2.154 | 0.033 | ||

| No | 47 | 42.62 ± 3.72 | ||

| Yes | 73 | 44.23 ± 4.19 |

Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that social support was negatively correlated with stigma (r = -0.691, P < 0.05), and anxiety and depression were positively correlated with stigma (r = 0.506, 0.382, P < 0.05) as shown in Figure 1.

Stigma was used as the dependent variable, and the variables of age, education level, smoking status, family monthly income per-capita, pension, disease concealment tendency, social support, anxiety, and depression were all subjected to regression analysis. A normality test was performed during the analysis, as was a residual analysis of the fitted model. The residuals followed a normal distribution. The assignments of each variable and dummy variable are presented in Table 5.

| ID | Variable | Assignment |

| X01 | Age (a) | 0 = 65-75, 1 ≥ 75 |

| X02 | Education level | Junior high school and below (Z1 = 0, Z2 = 0, Z3 = 0); High school or technical secondary school (Z1 = 0, Z2 = 1, Z3 = 0); College or above (Z1 = 0, Z2 = 0, Z3 = 1) |

| X03 | Smoking | 0 = No, 1 = Yes |

| X04 | Average monthly family income (CNY) | > 5000 (Z1 = 0, Z2 = 0, Z3 = 0); 3000-5000 (Z1= 0, Z2= 1, Z3 = 0); < 3000 (Z1 = 0, Z2 = 0, Z3 = 1) |

| X05 | Pension | 0 = No, 1= Yes |

| X06 | Tendency to conceal illness | 0 = No, 1 = Yes |

| X07 | Social support | Actual measuring |

| X08 | Anxiety | Actual measuring |

| X09 | Depression | Actual measuring |

Before entering the regression equation, the variables were subjected to a multicollinearity diagnosis. The variance inflation factor ranged from 1.095 to 1.469, suggesting that the respective variables had no collinearity problems and could be subjected to regression analysis. The results showed that age, smoking status, social support, anxiety, and depression entered the linear regression equation and were predictors of stigma in older patients after leukemia diagnosis (all P < 0.05). The determination coefficients were R2 = 0.644 and the adjusted R2 = 0.607 (Table 6).

| Variable | Group | β | SE | β’ | t | P value |

| Constant | 55.607 | 5.278 | —— | 10.535 | < 0.05 | |

| Age (a) | 1.442 | 0.494 | 0.175 | 2.918 | 0.004 | |

| Education level | Junior high school and below | 0.604 | 0.632 | 0.066 | 0.955 | 0.342 |

| High school or technical secondary school | 0.227 | 0.572 | 0.027 | 0.396 | 0.693 | |

| Smoking | 1.479 | 0.533 | 0.174 | 2.775 | 0.007 | |

| Average monthly family income (CNY) | < 3000 | 0.938 | 0.654 | 0.099 | 1.433 | 0.155 |

| 3000-5000 | 0.531 | 0.565 | 0.064 | 0.940 | 0.349 | |

| Pension | -0.160 | 0.514 | -0.02 | -0.311 | 0.757 | |

| Tendency to conceal illness | 0.885 | 0.514 | 0.107 | 1.721 | 0.088 | |

| Social support | -0.670 | 0.097 | -0.472 | -6.873 | < 0.05 | |

| Anxiety | 0.079 | 0.034 | 0.162 | 2.351 | 0.021 | |

| Depression | 0.093 | 0.043 | 0.137 | 2.192 | 0.031 |

The scores for the three dimensions of SIS were 13.82 ± 2.41 points, 7.32 ± 1.33 points, and 22.47 ± 2.97 points, with a total score of 43.60 ± 4.07 points. This suggests that older patients with leukemia may face social exclusion and isolation and may also experience strong feelings of stigma and disease-related stigma. This may be attributable to several factors, the first of which is social cognition and prejudice. Leukemia is considered to be a serious disease that is strongly associated with death. Therefore, patients may feel themselves labeled as being "sick," and may subsequently face discrimination and exclusion from society. Social cognition and prejudice can lead to feelings of stigma and embarrassment[10]. The second potential reason concerns the discomfort and side effects that result from leukemia treatment. Leukemia treatment, which can include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and bone marrow transplantation, is often a challenging process[11,12]. These treatments can produce side effects and physical discomfort, for example, nausea, hair loss, and fatigue. Patients anticipate experiencing physical image barriers and declining bodily functions, which can lead to feelings of stigma and embarrassment, further intensifying their sense of stigma. Finally, older leukemia patients experience significant changes in terms of their quality of life. The diagnosis and treatment of leukemia can have a significant impact on patients' lives. Patients may require frequent medical checkups and treatments that disrupt and limit their daily lives. In Chinese culture, family expectations and pressures have a significant influence on individuals[13]. These changes may cause patients to feel a sense of shame and to lose their self-esteem, leading to further stigmatization. Hence, similarly to the results recorded in previous studies[5-7], most patients in this study reported experiencing varying levels of stigma. A study of patients with different types of cancer found that disease-related stigma was prevalent and was associated with factors such as sex, age, education level, and level of social support[14]. Our findings also indicated that the level of stigma experienced by older leukemia patients was comparatively lower than that of breast cancer patients (55.20 ± 12.15 points)[15] and oral cancer patients (50.17 ± 21.24 points)[16]. This may be related to societal cognition and acceptance, changes in appearance and image, and the influence of sex and gender roles.

The formation of disease-related stigma is complex and involves factors such as negative social evaluation, patients’ own lack of understanding, personality traits, family support, and societal care. One study found that stigma in cancer patients was related to the personality traits of individual patients, with patients with more introverted, neurotic, and depressive tendencies being more prone to experiencing disease-related stigma[17]. Another study found that family support and societal care significantly alleviated patients' disease-related stigma, improved their quality of life, and enhanced their psychological well-being[18].

The correlation analysis conducted in this study further supported these findings, revealing a positive correlation between anxiety, depression, and disease-related stigma and a negative correlation between social support and disease-related stigma. Anxiety and depression can make patients feel discouraged and hopeless, and cause them to engage in self-blame with regard to their illness, thereby exacerbating disease-related stigma[19]. These negative emotions can make patients overly sensitive to judgment and criticism from others, further deepening their sense of perceived stigmatization. Social support can provide emotional and informational support as well as practical assistance[20,21]. Together, this can help patients to cope with the difficulties and challenges that accompany a leukemia diagnosis and the resulting treatment. Such support can decrease feelings of loneliness, helplessness, and self-blame, thereby reducing disease-related stigma.

Linear regression analysis revealed that both age and smoking status were predictors of stigmatization in older patients with leukemia after diagnosis. Among these factors, age may have the greatest impact on stigma in older patients with leukemia. Liu et al[22] also emphasized this point in their study on the stigma experienced by patients with lung cancer. Leukemia treatment often requires significant medical resources and financial investment[23,24]. Thus, patients may be concerned that their illness will impose a burden on their families and society as a whole in terms of medical resources and finances. Older patients may also feel that they should be enjoying retirement and a peaceful life rather than facing a serious illness. It is worth noting that only 35.00% of patients reported having a monthly household income in excess of 5000 yuan, and that 55.83% of patients reported not having a pension, both of which are strong indicators of economic difficulties. Additionally, older adults may have limited knowledge and information about leukemia, which can create more doubts and anxieties about the disease, thereby increasing older patients’ perception of disease-related stigma. Smoking is an unhealthy lifestyle habit that may be associated with an increased risk of developing leukemia[25,26]. Upon being diagnosed with leukemia, patients may perceive their smoking habit to be one of the causes of their disease, leading to guilt and self-blame, which can further exacerbate their perception of disease-related stigma. In this study, social support, anxiety, and depression were identified as predictive variables. Social support had a positive impact on reducing stigma among older patients with leukemia, whereas anxiety and depression had the opposite effects. As mentioned earlier, social support can be further categorized as being instrumental or emotional[20,21], with both forms of support being crucial for patients. Patients who lack social support may feel more isolated and ashamed. Negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, can increase patients' level of self-denial and perception of stigma regarding their condition.

A number of coping strategies can be proposed in response to the factors identified as influencing disease-related stigma in older patients with leukemia. Providing detailed information and knowledge about leukemia to older patients, such as by emphasizing that the development of leukemia is not solely related to smoking but also to other genetic, environmental, and health factors may help to reduce patients' excessive self-blame for their smoking behavior and decrease their associated disease-related stigma. Establishing good communication and trust with patients, listening to their concerns and the emotions they are experiencing, and providing appropriate psychological support are other useful coping strategies. This can include providing emotional support, guiding patients to seek professional psychological counseling, or encouraging them to join support groups. Helping patients to find and join relevant leukemia support groups or organizations can also enable them to share their experiences and to receive emotional support from other patients. Finally, patients can communicate with their families and social organizations to seek economic support and assistance. Medical expenses and insurance matters should be discussed simultaneously with the relevant healthcare team to assist in alleviating patients’ financial burden.

This study has the following advantages: (1) It considers multiple factors that may influence patients’ perceived sense of stigmatization, including age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, average monthly household income, pension, tendency to conceal illness, level of social support, anxiety, and depression. This enables us to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of these factors on patients’ sense of stigmatization; (2) this study included older patients with leukemia from various socioeconomic backgrounds and age groups, thereby improving the overall representativeness and generalizability of the study results; and (3) this study identified a number of coping strategies for helping patients to deal with their own sense of stigmatization. These strategies can provide practical assistance and guidance to patients. However, the study also has some notable limitations: (1) The study only included specific types of older leukemia patients from specific regions, so the results may not be generalizable; and (2) the assessment of stigma in this study may have been based on patients’ own subjective feelings, as the study lacked more objective indicators or measurement tools.

Older patients with leukemia may experience strong feelings of stigmatization and disease-related stigma influenced by various factors. By gaining a deeper understanding of the formation of and factors influencing disease-related stigma, we can provide more comprehensive and effective psychological support and interventions for older patients. The results of this study also contribute to raising awareness and understanding of older patients with leukemia among healthcare teams and the public in general, promoting the need for greater social support and assistance.

| 1. | Wang YQ, Li HZ, Gong WW, Chen YY, Zhu C, Wang L, Zhong JM, Du LB. Cancer incidence and mortality in Zhejiang Province, Southeast China, 2016: a population-based study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134:1959-1966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sharma R, Jani C. Mapping incidence and mortality of leukemia and its subtypes in 21 world regions in last three decades and projections to 2030. Ann Hematol. 2022;101:1523-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Loughlin M, Dolezal L, Hutchinson P, Subramani S, Milani R, Lafarge C. Philosophy and the clinic: Stigma, respect and shame. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28:705-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Andersen MM, Varga S, Folker AP. On the definition of stigma. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28:847-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vrbova K, Prasko J, Ociskova M, Holubova M, Kantor K, Kolek A, Grambal A, Slepecky M. Suicidality, self-stigma, social anxiety and personality traits in stabilized schizophrenia patients - a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1415-1424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown JS, Thornicroft G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45:11-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1906] [Cited by in RCA: 1650] [Article Influence: 150.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nikus Fido N, Aman M, Brihnu Z. HIV stigma and associated factors among antiretroviral treatment clients in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2016;8:183-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Eliasson ET, McNamee L, Swanson L, Lawrie SM, Schwannauer M. Unpacking stigma: Meta-analyses of correlates and moderators of personal stigma in psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;89:102077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao Q, Huangfu C, Li J, Liu H, Tang N. Psychological Resilience as the Mediating Factor Between Stigma and Social Avoidance and Distress of Infertility Patients in China: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:391-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nair M, Kumar P, Pandey S, Harshana A, Kazmi S, Moreto-Planas L, Burza S. Refused and referred-persistent stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS in Bihar: a qualitative study from India. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e033790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Osman AEG, Deininger MW. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Modern therapies, current challenges and future directions. Blood Rev. 2021;49:100825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Carnot Uria J, Hernández Cruz C, Muñío Perurena J, Torres Yribar W, Diego de la Campa J, Del Castillo Carrillo C, Rodríguez Fraga Y, López Silva JA, Cepero Llauger K, Pardo Ramírez IK, García García A, Sweiss K, Patel PR, Rondelli D. Bone Marrow Transplantation in Patients With Acute Leukemia In Cuba: Results From the Last 30 Years and New Opportunities Through International Collaboration. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sun KS, Lam TP, Lam KF, Lo TL. Barriers and facilitators for psychiatrists in managing mental health patients in Hong Kong-Impact of Chinese culture and health system. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2018;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang Z, Yu T, Wu S, Hu A. Correlates of stigma for patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:1195-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jin R, Xie T, Zhang L, Gong N, Zhang J. Stigma and its influencing factors among breast cancer survivors in China: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;52:101972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tan C, Zhong C, Mei R, Yang R, Wang D, Deng X, Chen S, Ye M. Stigma and related influencing factors in postoperative oral cancer patients in China: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:5449-5458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Solmi M, Granziol U, Danieli A, Frasson A, Meneghetti L, Ferranti R, Zordan M, Salvetti B, Conca A, Salcuni S, Zaninotto L. Predictors of stigma in a sample of mental health professionals: Network and moderator analysis on gender, years of experience, personality traits, and levels of burnout. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63:e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li B, Liu D, Zhang Y, Xue P. Stigma and related factors among renal dialysis patients in China. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1175179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lynch H, McDonagh C, Hennessy E. Social Anxiety and Depression Stigma Among Adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:744-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhao X, Sun M, Yang Y. Effects of social support, hope and resilience on depressive symptoms within 18 months after diagnosis of prostate cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zamanian H, Amini-Tehrani M, Jalali Z, Daryaafzoon M, Ramezani F, Malek N, Adabimohazab M, Hozouri R, Rafiei Taghanaky F. Stigma and Quality of Life in Women With Breast Cancer: Mediation and Moderation Model of Social Support, Sense of Coherence, and Coping Strategies. Front Psychol. 2022;13:657992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu XH, Zhong JD, Zhang JE, Cheng Y, Bu XQ. Stigma and its correlates in people living with lung cancer: A cross-sectional study from China. Psychooncology. 2020;29:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mau LW, Preussler JM, Burns LJ, Leppke S, Majhail NS, Meyer CL, Mupfudze T, Saber W, Steinert P, Vanness DJ. Healthcare Costs of Treating Privately Insured Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia in the United States from 2004 to 2014: A Generalized Additive Modeling Approach. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38:515-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mozessohn L, Cheung MC, Mittmann N, Earle CC, Liu N, Buckstein R. Real-World Costs of Azacitidine Treatment in Patients With Higher-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes/Low Blast-Count Acute Myeloid Leukemia. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e517-e525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Larsson SC, Burgess S. Appraising the causal role of smoking in multiple diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. EBioMedicine. 2022;82:104154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yi M, Li A, Zhou L, Chu Q, Song Y, Wu K. The global burden and attributable risk factor analysis of acute myeloid leukemia in 195 countries and territories from 1990 to 2017: estimates based on the global burden of disease study 2017. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/