Published online Apr 19, 2023. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i4.191

Peer-review started: December 10, 2022

First decision: January 31, 2023

Revised: February 6, 2023

Accepted: March 27, 2023

Article in press: March 27, 2023

Published online: April 19, 2023

Processing time: 129 Days and 1.7 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic produced changes in intensive care units (ICUs) in patient care and health organizations. The pandemic event increased patients’ risk of developing psychological symptoms during and after hospitalisation. These consequences also affected those family members who could not access the hospital. In addition, the initial lack of knowledge about the virus and its management, the climate of fear and uncertainty, the increased workload and the risk of becoming infected and being contagious, had a strong impact on healthcare staff and organizations. This highlighted the importance of interventions aimed at providing psychological support to ICUs, involving patients, their relatives, and the staff; this might involve the reorganisation of the daily routine and rearrangement of ICU staff duties.

To conduct a systematic review of psychological issues in ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic involving patients, their relatives, and ICU staff.

We investigated the PubMed and the ClinicalTrials.gov databases and found 65 eligible articles, upon which we commented.

Our results point to increased perceived stress and psychological distress in staff, patients and their relatives and increased worry for being infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 in patients and relatives. Furthermore, promising results were obtained for some psychological programmes aiming at improving psychological measures in all ICU categories.

As the pandemic limited direct inter-individual interactions, the role of interventions using digital tools and virtual reality is becoming increasingly important. All considered, our results indicate an essential role for psychologists in ICUs.

Core Tip: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic produced changes in patient care and organization of intensive care units (ICUs). The pandemic event increased patients’ risk of developing psychological symptoms during and after hospitalisation. We carried out a systematic review of the psychological issues raised in ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic which concerned patients, their relatives, and the ICU staff. Our results point to increased perceived stress and psychological distress in staff, patients and their relatives and increased worry for being infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 in patients and relatives. Promising results were obtained for some psychological programmes and interventions using digital tools and virtual reality aiming at improving psychological measures in all ICU categories.

- Citation: Monti L, Marconi E, Bocci MG, Kotzalidis GD, Mazza M, Galliani C, Tranquilli S, Vento G, Conti G, Sani G, Antonelli M, Chieffo DPR. COVID-19 pandemic in the intensive care unit: Psychological implications and interventions, a systematic review. World J Psychiatry 2023; 13(4): 191-217

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v13/i4/191.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i4.191

Intensive care unit (ICU) utilisation during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic accounted for around 25% of patients hospitalised during the February 2020 to September 2021 period in 21 United States Healthcare systems[1]. The COVID-19 pandemic has produced changes in ICUs both in patient care and in hospital care organization. On the one hand, the high burden of stress that patients usually experience in the ICU, has been exacerbated by the fear of the virus and the need to isolate, especially from family members. The pandemic has consequently increased the patient’s risk of developing important psychological symptoms during and after hospitalization[2-4]. In addition, family members also experienced psychological symptoms due to the lack of access to the hospital, as this keeps them away from their loved ones and made it more difficult to exchange information with health workers[5]. Psychological symptoms associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, despite being more severe in the patient population, match those of relatives[6]. Finally, the lack of knowledge about the virus and its management, the climate of fear and uncertainty, increased workload, and the risk of becoming infected and infecting loved ones, had a great impact on staff[7-9]. This highlighted the importance of interventions aiming to provide psychological support to the treatment team, to reorganise the daily routine, and to characterise the role of the professionals working in an ICU.

With the awareness that the COVID-19 emergency is not over, the aim of this review was to highlight the changes and developments occurring in ICUs during the pandemic, knowing that many of its characteristics and changes are still important and will probably be in the future. The need to monitor the psychological phenomena taking place in ICUs during the COVID-19 period and to implement adequate interventions in the same structures has already been stressed in neonatal/paediatric[9,10-13] and adult age[14]. A review focused on the role of the psychologist in paediatric ICUs[15], and other two in adults were systematic reviews, one on informational and educational interventions in ICUs[16], the other on bereavement support[17], while one study identified three areas of utility of a psychologist in an ICU, namely, attention to patients at the ICU, attention to family members or caregivers, and work with health personnel[18]. There are currently no studies collecting experiences and evidence of effectiveness of psychological interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, through this review we intend to investigate the psychological characteristics of ICU admission during the pandemic, through the assessment of the perspectives of the various involved individuals, i.e., patients, family members, and staff members, and on the interventions that the psychologist, along with the medical team, enforced to deal with the health emergency.

We will start by describing patients’ most frequent psychological repercussions of ICU admission and stay. Subsequently, we will summarise the elements of the main psychological characteristics of patients, family members, and caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the pandemic limited direct, person-to-person interindividual interactions, with a concomitant rise in the use of digital homework, we found it interesting to dedicate a section of this review to interventions with digital tools. During the pandemic, these tools proved to be very effective (besides being the only available) in facilitating communication at various levels. Within this framework, we also highlight the role of virtual reality (VR) used in intensive care to treat the psychological consequences and promote the well-being of patients hospitalised with COVID-19 (and their relatives).

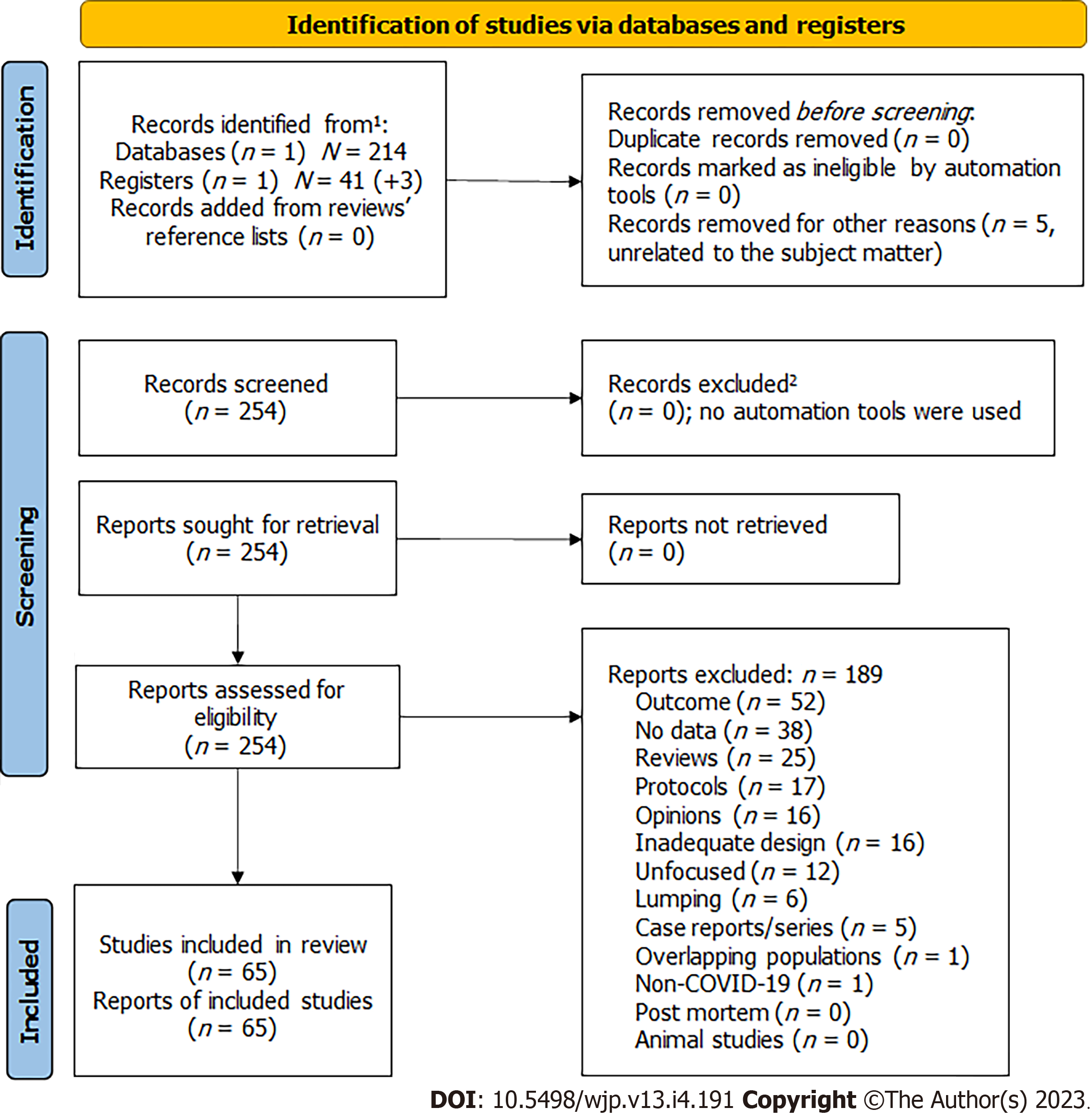

To identify evidence of psychological issues and interventions in ICUs, we searched the PubMed database adopting the following search strategy: COVID-19 AND (“Intensive Care Unit” OR ICU) AND psychol* AND (implicat* OR intervent*), which produced on September 30, 2022, 214 results. We also searched the ClinicalTrials.gov database using the strategy Condition or disease: COVID-19 and Other terms: intensive care unit AND psychological, which produced 41 results on the same date. Eligibility depended on being an experimental work having data, either epidemiological or interventional. Excluded were reviews (and meta-analyses as well as guidelines; n = 25), case reports and series (n = 5), opinion articles (n = 16, editorials, comments on other articles, and reports without data), protocols of future studies (n = 17), articles not reporting on psychological outcomes or interventions, not involving ICUs, or not involving COVID-9 (collectively labelled as outcome, n = 52), studies not providing results (n = 38), studies lumping ICU data with data from other wards without providing separate data for ICUs (n = 6), studies with overlapping populations (n = 1, in which case only the article with the higher sample size would have been selected, provided it was higher in quality than others), studies with inadequate design to obtain the desired results (n = 16), unfocused articles (n = 12), papers unrelated to the subject matter (n = 5), post mortem studies (n = 0), and animal studies (n = 0).

Reviews/meta-analyses and guidelines were excluded but we thoroughly searched their reference lists for studies that possibly eluded our database searches. Duplicates were also to exclude if occurring in both searched databases (n = 0). When adding records concerning ClinicalTrials.gov to those of PubMed, we took care to substitute those that had their NCT number published within PubMed with the published article and rate it as appropriately. One ClinicalTrials.gov record produced four additional articles published with its NCT number, thus amounting to a grand total of 259 records. ClinicalTrials.gov added 1 eligible article; the 64 identified by PubMed. PubMed results did not overlap with those of ClinicalTrials.gov. We found no duplicates in our searches. Of the records identified by our ClinicalTrials.gov search, 19 were completed, but only 1 of them had results (and was not eligible, record 29 in Supplementary Material), 9 were still recruiting, 7 were active, but not recruiting, 1 was not yet recruiting, 3 had unknown status, and 2 were terminated (one in Malaysia for logistical problems/administrative issues, the other in Turkey, due to technical reasons). Most projects were based in France (n = 19, 1 in its extra-European territories), other 9 in Northern Europe and British isles (5 Belgium, 2 the Netherlands, 1 Denmark, and 1 United Kingdom), 6 in Southern Europe (3 Spain, 2 Turkey, and 1 Italy), 5 in the Americas (3 United States, 1 Brazil, and 1 Colombia), 1 in Asia (Malaysia), and 1 in Africa (Egypt) (Supplementary Material). The first was first-posted on June 19, 2019, the last on June 16, 2022, indicating early and enduring interest in the subject. Qualitative analyses were included if they adequately assessed psychological outcomes, but unfortunately, most did not. We assessed eligibility by reaching consensus among five authors (Monti L, Tranquilli S, Mazza M, Marconi E, and Kotzalidis GD) through Delphi rounds; no more than two were necessary to establish it. The results of the search are shown in Figure 1[19]. The list of studies considered is in the Supplementary Material in a Table, where reasons for exclusion are provided for each study (Supplementary Material). The final number of included studies was 65, spanning from July 2, 2020 to September 23, 2022. A summary of their results is provided in Table 1.

| Ref. | Type | Population | Design | Outcomes and assessments | Results | Conclusions and observations |

| Sayde et al[138], 2020 | C-S survey | 265 ICU patients recruited, 20 refused, 185 excluded, 35 included: 17: Intervention group, (16 female, 11 male); 18 patients control group (15 female,13 male) | Diary and questionnaire administered 1 (BL), 4, 12, and 24 wk after ICU discharge (September 2017 to September 2018) in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States | Psychological distress, (IES-R), Anxiety and Depression (PHQ-8; HADS; GAD-7) | Controls had a significantly greater decrease in PTSD, hyperarousal, and depression symptoms at week 4 compared to the intervention group. No significant differences in other measures, or at other follow-ups. Both study groups exhibited clinically significant PTSD symptoms at all timepoints after ICU discharge | Diary increased awareness of the psychological support available to ICU survivors and family members |

| Huang et al[139], 2020 | C-S online survey | 6523 people with contact history, completed the survey, 260 were excluded, 6261 included. 3585 female (57.3%), 2676 male (42.7%) | Online questionnaire sent to participants of Hubei province and outside Hubei province, China, from February 10 to 15, 2020 | Tested depression (PHQ-9) and public perceptions in response to the COVID-19 outbreak | Most people endorsed preventive and avoidance behaviours. People from Hubei, with contact history, and people who were infected or whose family members were infected by COVID-19, had a much higher prevalence of depression and anxiety | Assessing public response, perception, and psychological burden during the outbreak may help improving public health recommendations and deliver timely psychological intervention |

| Leng et al[140], 2021 | C-S survey | 90 ICU nurses; 65 female (72.2%), 25 male (27.8%) | Tests administered to ICU Wuhan (China) nurses, from 11 to 18 March 2020 | PTSD (PTSD Checklist-Civilian and PSS), related to demographic survey and 2 open questions | Nurses have elevated PTSD levels. Nurses’ stress and PTSD symptoms were positively correlated. Isolated environment, concerns about personal protective equipment shortage and usage, physical and emotional exhaustion, intensive workload, fear of being infected, and insufficient work experiences with COVID-19 were a major stress source | Even highly skilled and resilient nurses experienced some degree of mental distress, such as PTSD symptoms and perceived stress |

| Lasater et al[80], 2021 | C-S analyses | ICU nurses and ICU patients: First sample 4298 medical-surgical nurses; second sample 2182 ICU nurses | Staffing data collected from registered nurses in New York and Illinois using HCAHPS and AHA, between 16-12-2019–24-2-2020 | Information on patient satisfaction, hospital characteristics | Over half the nurses experienced high burnout. Half gave their hospitals unfavourable safety grades and two-thirds would not definitely recommend their hospitals. One-third of patients rated their hospitals less than excellent and would not definitely recommend it to others | Hospital nurses had burn-out and were working in understaffed conditions in the weeks prior to the first wave of COVID-19 cases, thus increasing public health risks |

| Jain et al[81], 2020 | C-S online survey | 512 Indian anaesthesiologists, 227 female (44.3%), 285 male (55.7%) | Online questionnaire sent to anaesthesiologists across India from 12-5-2020 to 22-5-2020 | Anxiety (GAD-7) and Insomnia (ISI) | Elevated COVID-19-related anxiety and insomnia levels of anaesthesiologists. Age < 35 yr, female sex, being married, resident doctors, fear of infection to self or family, fear of salary deductions, increase in working hours, loneliness due to isolation, food and accommodation issues and posting in COVID-19 duty were risk factors for anxiety. < 35 yr, unmarried, those with stress due to COVID-19, fear of loneliness, issues of food and accommodation, increased working hours favour insomnia | Anaesthesiologists on COVID-19 duty suffer from anxiety and insomnia |

| Kirolos et al[82], 2021 | LS | 41 families with a baby at NICU | Multicentre service evaluation in five United Kingdom neonatal care units, between July and November 2019 | Surveys contained quantitative (9-point Likert scale, or closed-ended yes/no responses) and qualitative items (open comment boxes) | In post-implementation surveys (n = 42), 88% perceived a benefit of the service on their neonatal experience. 71% (n = 55) felt the service had a positive impact on relationships with families | Asynchronous video supports models of family integrated care and can mitigate family separation |

| Lasalvia et al[83], 2020 | C-S online survey | 2195 ICU HCWs; female 539 (24.7 %), male 1647 (75.3) | All healthcare and administrative staff of Verona University Hospital (Veneto, Italy) from April to May 2020 | Psychological distress (IES-R), Anxiety (SAS) and mental health (PHQ-9) | 63.2% of participants reported COVID-related traumatic experiences at work; 53.8% showed symptoms of post-traumatic distress; 50.1% showed symptoms of clinically relevant anxiety; 26.6% symptoms of moderate depression | The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare staff working in a highly burdened north-east Italy is high and to some extent higher than that reported in China |

| Ou et al[84], 2021 | C-S study | 92 nurses in isolation ward, female 85 (92.4%); male 7 (7.6%) | Test was administered to nurses in isolation ward, the Guangdong Province of China, in February 2020 | Resilience and psychopathological symptoms (CD-RISC2; SCL-90) | Total resilience score was 87.04 ± 22.78. SCL-90 score ranged 160-281 (202.5 ± 40.79). Only 8.70% of nurses (n = 8) scored > 160 on the SCL-90, suggesting positive symptoms. Most nurses had 0 to 90 positive self-assessment items (median 14); 19.57% (n = 18) had > 43 positive items to CD-RISC 2 | High resilience promotes physical and mental health, and may be improved by training, psychological interventions, and full use of hospital resources |

| Vlake et al[69], 2020 | Case report | One COVID-19 patient (male), age: 57 yr | Test for evaluating COVID-19 ICU-VR intervention in one Dutch man with COVID-19 | Anxiety and depression (HADS) and psychological distress (IES-R) | One week after receiving ICU-VR, levels of PTSD, anxiety, and depression had normalised and stayed normal 6 mo after discharge | Virtual realty improved psychological rehabilitation outcomes, hence they should be considered by clinicians for the treatment of ICU-related psychological sequelae after COVID-19 |

| Fernández-Castillo et al[85], 2021 | C-S survey | 17 nurses: 6 male, 11 male | 17 nurses of a tertiary teaching hospital in Southern Spain, from 12-30 April 2020 | Semi-structured videocall interviews | Four main themes emerged from the analysis and 13 subthemes: “providing nursing care”, “psychosocial aspects and emotional lability”, “resources management and safety” and “professional relationships and fellowship” | Nursing care has been influenced by fear and isolation, making it hard to maintain humanisation of health care |

| Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group et al[86], 2021 | C-S telephone survey | 834 eligible COVID-19 survivors: 478 evaluated (201 male, 277 female) | Survivors of COVID-19 in France underwent telephone assessment 4 mo after discharge, between July and September 2020 | Respiratory, cognitive, and functional symptoms (Q3PC cognitive screening questionnaire, symptom Checklist and 20-item Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; SF-36; cognitive impairment (MoCA) | 244 patients (51%) declared at least 1 symptom absent before COVID-19: Fatigue in 31%, cognitive symptoms in 21%, and new-onset dyspnoea in 16%. The median 20-item Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory score (n = 130) was 4.5 for reduced motivation and 3.7 for mental fatigue. The median SF-36 score (n = 145) was 25 for the subscale “role limited owing to physical problems”. Among 94 former ICU patients, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were observed in 23%, 18%, and 7%, respectively. The left ventricular ejection fraction was < 50% in 8 of 83 ICU patients (10%) | 4 mo after hospitalisation for COVID-19, a cohort of patients frequently reported previously absent symptoms |

| Stocchetti et al[87], 2021 | C-S online study | Of 271 medical staff working in this ICU, 136 included: 84 nurses (62%) and 52 physicians (38%) | Nurses and physicians working in this ICU participated to online survey in January 2021 | Burnout (MBI), anxiety (HADS); resilience (RSA) and Insomnia (ISI) | 60% of participants show high burnout level: Nurses reported significantly higher scores of anxiety and insomnia levels. 45 % reported symptoms of depression, and 82.4% of the staff showed moderate-to-high levels of resilience | The COVID-19 pandemic can have a significant impact on ICU staff. Effective interventions needed to maintain healthcare professionals’ mental health and relieve burnout |

| Kirk et al[12], 2021 | C-S online study | 430 of 458 paediatric HCWs, concluded the online survey | Online survey administered to paediatric HCWs in the emergency, ICU and infectious disease units from April 28 to May 5 2020 | Depression and Anxiety symptoms (DASS-21) | 168 (39.1%) of respondent showed depression, 205 (47.7%) anxiety and 106 (24.7%) symptoms of stress. Depression reported in the mild (47, 10.9%), moderate (76, 17.7%), severe (23, 5.3%) and extremely severe (22, 5.1%) categories. Anxiety (205, 47.7%) and stress (106, 24.7%) were reported in the mild category only | A high prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress was reported among frontline paediatric HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Yang et al[88], 2021 | C-S online study | Of 1075 contacted individuals, 1036 front-line HPCD completed the online survey: Female 755 (72.9%), male 288 (27.1). 874 (84.4%) nurses, 162 (15.6%) physicians | 1036 front-line HPCDs exposed to COVID-19 were tested online from 5 to 9 March 2020 in Wuhan, China | Sleep, insomnia, emotional regulation (RESE) | 543 (52.4 %) reported symptoms of sleep disorders. HPCD for patients with COVID-19 in China reported experiencing sleep disturbance burdens, especially those having exposure experience and working long shifts | RESE is an important resource for alleviating sleep disturbances and improving sleep quality |

| Moradi et al[89], 2021 | C-S survey | 17 nurses in ICUs: 5 males and 12 females | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were administered to nurses in ICUs of Urmia, Iran | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Four challenges throughout the provision of care for COVID-19 patients: ‘organization’s inefficiency in supporting nurses’, ‘physical exhaustion’, ‘living with uncertainty’ and ‘psychological burden of the disease | A profound understanding of ICU nurses’ challenges while caring for COVID-19 patients is needed to increase healthcare quality |

| Bruyneel et al[90], 2021 | C-S online survey | 1135 ICU nurses: Female 892 (78%); male 243 (22%) | Nurses in the French-speaking part of Belgium completed a web-based survey, April 21-May 4, 2020 | Burnout (MBI) | 68% burnout level. 29% of ICU nurses were at risk of depersonalisation, 31% of reduced personal accomplishment, and 38% of emotional exhaustion | Burnout risk requires monitoring and implementation of interventions to prevent it and manage it |

| Shariati et al[91], 2021 | LS online survey | 67 family members of COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU | Longitudinal pre-post intervention online survey of 67 family members of COVID-19 ICU patients in three hospitals in Iran; May to August 2020 | Stress symptoms (PSS-14) | Mean PSS-14 post-intervention significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (P < 0.001) | Use of web-based communication between nurses and family members was effective in reducing perceived stress |

| Kok et al[92], 2021 | LS survey | Open cohort of ICUs professional: BL survey 252 respondents, response rate: 53%, male 66 (26.2%), female 186 (73.8%); and follow-up 233 respondents, response rate: 50%, male 65 (27.9%), female 168 (72.1%) | BL survey collected in October-December 2019 and follow-up survey sent in May-June 2020 to a university medical centre and a large teaching hospital in the Netherlands | Semi-structured interview form | The prevalence of burnout symptoms was 23.0% before COVID-19 and 36.1% after, with higher rates in nurses (38.0%) than in physicians (28.6%). Post-COVID-19 incidence rate of new burnout cases among physicians was higher (26.7%) than among nurses (21.9%). Higher prevalence of burnout symptoms after the beginning of the pandemic | Overburdening of ICU healthcare personnel during an extended period leads to burnout symptoms |

| Kürtüncü et al[93], 2021 | C-S survey | 18 COVID-19 patients: 4 females and 14 males | Telephone-conducted semi-structured interview of 18 ICU patients in Turkey; March-September, 2020 | Semi-structured interview form | Interventions in ICUs are able to promote communication with patients and are essential for achieving positive circumstances | Families of missing patients may benefit from interventions of nurses aimed at working-through the loss and providing family support and care during their critical illness |

| Martillo et al[94], 2021 | C-S online survey | 45 COVID-19 ICU patients: Male 33 (73.3%), female 10 (22.2%) | Single-centre descriptive cohort study of ICU patients at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York; April 21 to July 7, 2020 | Insomnia (ISI), mental health (PHQ-9), QoL (EQ-5D-3L), PTSD (PCL-5), telephone cognitive assessment (MoCA) | 22 patients (48%) reported psychiatric impairment, and four (8%) had cognitive impairment. 38% at least mild depression, and 18% moderate-to-severe depression. 8% PTSD. 9% had impaired cognition | Severe COVID-19-related symptoms associated with high risk of developing PICS. Planning needed for appropriate post-ICU care |

| Donkers et al[95], 2021 | C-S online survey | 355 nurses, 108 supporting staff and 41 ICU physicians from 84 ICUs: 124 males, 380 females | Online questionnaire sent by email to Dutch ICU nurses and supporting staff from 7 April to 11 June, 2020 | MD for HCWs (MMD-HP), Ethical Decision-Making (EDMCQ) | MD levels higher for nurses than others; “Inadequate emotional support for patients and their families” was the highest-ranked cause of MD for all participants; all participants judged positively the ethical climate regarding the culture of mutual respect, ethical awareness, and support | Targeted interventions on MD are important for improving the mental health of critical care professionals and the quality of patient care |

| Fteropoulli et al[96], 2021 | C-S online survey | 1071 healthcare personnel: 73% females, and 27% males | Anonymous online survey administered. May 25 to October 27, 2020, in Cyprus | QoL (WHOQOL-Brief), anxiety (GAD-7), depression (PHQ-8), burnout (CBI), and coping (Brief COPE) | 27.6% moderate and severe anxiety, 26.8% depression. Being female, nurse or doctor, working in frontline units, perceptions of inadequate workplace preparation to deal with the pandemic and using avoidance coping were risk factors | There are several risk factors for psychological distress during the pandemic, which may be individual, psychosocial, and organisational |

| Peñacoba et al[97], 2021 | C-S online survey | 308 intensive care nurses: Female 268 (87%) and male 40 (13%) | Online form used to collect data from surgical and general critical care units in a public Spain Hospital, March 2020 to June 2020 | Stress subscale (depression, anxiety, and stress in Spanish DASS-21), physical and mental health-related QoL (SF-36), GSES, and resilience (RS-14) | Greater perception of self-efficacy related to lower perception of stress and greater resilience, while higher resilience was linked to greater physical and mental health | Stress is related to physical and mental health factors which are linked to QoL through self-efficacy and resilience |

| Wozniak et al[98], 2021 | C-S online study | 3461 HCWs of 352 ICU | Online data collected from May 28 to July 7, 2020, at HUG, Switzerland | Socio-demographic data, lifestyle changes, anxiety (GAD-7; PHQ-9), psychological distress (PDI; WHO-5) | 145 (41%) reported poor well-being, 162 (46%) anxiety, 163 (46%) depression, 76 (22%) peritraumatic distress. Working in ICU more than other departments changes eating habits, sleeping patterns, and alcohol consumption (P < 0.01) | High prevalence of anxiety, depression, peritraumatic distress and poor well-being during the first COVID-19 wave among HCWs, especially in ICU |

| Li et al[99], 2021 | C-S survey | 78 ICUs nurses: Female 4 (17.95%), male 64 (82.05%) | Data from 78 ICU nurses in Beijing COVID-19 hospital during March 2020 | Depression (SDS), stress (PPS) | 44.9% (n = 35) reported depressive symptoms, stress perception; work experience in critical diseases, and education are risk factors for depression | Work experience in critical illness is linked to depression. Psychological intervention may reduce it |

| Manuela et al[100], 2021 | C-S survey | 34 females, mothers of premature infants born before 32 wk of gestational age; 20 pre-COVID-19 period vs 14 during COVID-19 pandemic | 20 mothers of premature infants recruited at HUG, CH, January 2018 to February 2020 before COVID-19 vs 14 mothers from November 2020 to June 2021 | Postnatal depression (EPDS); (PSS:NICU), attachment (MPAS) | No significant differences for depression, stress, and attachment between the two groups; “trend” towards increase of depression symptoms in mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic; depression correlated with attachment and stress scores | Protective family-based actions and appropriate interventions to support parents during the COVID-19 pandemic can reduce depression and stress of mothers of premature infants |

| Nijland et al[76], 2021 | LS survey | Of 326 ICU nurses, 138 (42.33%) participated; 86 VRelax users, male 13 (15%), female 73 (85%) and 52 non-users, male 9 (17%), female 43 (83%) | VRelax intervention investigated in Dutch ICU nurses in May, 2020 | Single-question VAS-stress scale | VR reduced stress by 36% (mean difference = 14.0 ± 13.3, P < 0.005). 62% of ICU nurses rated VRelax as helpful to reduce stress | VRelax is effective in reducing immediate perceived stress |

| Scheepers et al[101], 2021 | LS survey | Of 203 ICU and internal medicine staff, 103 residents (50.1%) participated | ICU and Internal medicine staff of AMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands tested during the first wave of COVID-19, March 15 to June 30, 2020 | Explored residents’ perceptions of well-being (well-being survey), and their perceived support of the well-being program during the COVID-19 pandemic | Residents working in the ICU reported significantly lower levels of mental well-being than internal medicine residents | Well-being programmes for ICU staff need to address ICU-specific stressors, enhancing supervision and peer support |

| Liu et al[102], 2021 | Study 1: LS survey; study 2: LS survey | Study 1: Of 268 ICU nurses and 26 head nurses, 258 completed the survey: Female 220 (85.27%), male 38 (14.73%). Study 2: 64 ICU medical professionals: Female 40 (65.57%), male 24 (34.43%) | Study 1: ICU nurses of major Chengdu hospital, China, recruited. Retested after 3 wk for work engagement and rated by head nurses for taking-charge behaviour after further 3 wk. Study 2: ICU medical staff of same Chinese hospital completed scales on early March, 2020 and 2 wk later | Studies 1-2: Perceived COVID-19 crisis strength and work meaningfulness assessed with 5-point Likert scales, and demographic data. Self-rating of work engagement and clinician rating of taking-charge behaviour | Study 1: Health worker’sperceived COVID-19 crisis strength exerted a more negative effect on his or her work engagement and taking charge at work. Study 2: The interventions significantly decreased perceived COVID-19 crisis strength and increased work meaningfulness for medical staff in an ICU | Study 1: Frontline health workers worldwide have regarded the COVID-19 crisis as an extraordinarily stressful event. Study 2: Interventions are important for reducing stress during COVID-19 pandemic |

| Carmassi et al[103], 2021 | C-S survey | 265 frontline HCWs: Male 84 (31.7%), female 181 (68.3%) | Data was recruited in a sample of frontline HCWs at a major university hospital in Pisa, Italy, April 1 to May 1, 2020 | PTSS (IES-R), anxiety (GAD-7), depression (PHQ-9), assess work and social Functioning (WSAS) | Subjects with acute PTSS have higher levels of PTSS, depressive symptoms, and moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms | More long-term studies are needed to evaluate the impact of psychopathology on the socio-occupational functioning of health professionals |

| Secosan et al[104], 2021 | C-S survey | Of 200 frontline HCWs, 126, 63% (32 nurses and 94 physicians) participated; male 35.7%, female 64.3%; 42.8% single, 52.3% married, 4.7% divorced | Data collected from Romanian frontline HCWs, March to April 2020 | Psychological capital (PsyCap) (PCQ) related to anxiety and depression (DASS-21), burnout (MBI) | High anxiety predicts lower emotional exhaustion and a low level of mental health complaints about healthcare professionals when PsyCap is high | PsyCap is may decrease the impact of anxiety and depression on psychological outcomes in frontline HCWs. Psychological interventions can help ICUs staff |

| Scarpina et al[105], 2021 | C-S survey | 60 patients who survived COVID-19 infection: Male 58.3%, female 41.7% | Participants had been recruited at the COVID-19 post-ICU, from May 2020 to January 2021, in Italy | Fearful facial expressions recognition, perceived psychological functioning, Empathy (4-point Likert scale questionnaire) | Altered detection and recognition of fearful expressions and altered processing of fearful expressions in individuals who survived COVID-19 infection | Altered emotional face recognition could represent psychological distress; psychological interventions in rehabilitative settings can be helpful |

| Kapetanos et al[106], 2021 | C-S survey | 381 HCWs: 72.7% nurses (202 males, 75 males) 12.9% physicians (28 males, 21 males), 14.4% other occupations (18 males; 7 males) | Data on mental health status of HCWs collected from healthcare professionals from all over Cyprus from May to June 2020 | 64-item, self-administered questionnaire, which included DASS21 and MBI | Prevalence of 28.6% anxiety, 8.11% stress, 15% depression, and 12.3% burnout. Environmental changes included increased working hours, isolation, and separation from family | Also the second wave of the pandemic impaired psychological health of HCWs |

| Manera et al[107], 2022 | C-S survey | 152 COVID-19 patients: 101 males, 51 females | Retrospective assessment of post-infectious SARS-CoV-2 patients at Maugeri Scientific Clinical Institutes, Northern Italy, May 2020 to May 2021 | Cognitive measures (MMSE) as related to disease severity (at-risk vs not at-risk: Neuro+ vs Neuro-) | Mild-to-moderate patients (26.3%) showed impaired MMSE performances; ICU patients made less errors (P = 0.021) on the MMSE than non-ICU patients. Age negatively influenced MMSE performance. For Neuro-patients, steroidal treatment improved MMSE scores (P = 0.025) | Mild-to-moderate patients, with mechanical ventilation who however are not admitted to an ICU, are more likely to suffer from cognitive deficits, independently from their aetiology |

| Mollard et al[108], 2021 | C-S survey | 885 postpartum women, 82.3% married | English-speaking adult postpartum women who gave birth in US hospitals from 1 March to 9 July 2020 participated in survey between 22 May to 22 July 2020 | Demographic and health variables measured with self-report questionnaires; stress (PSS-10), Mastery (PM), and resilience (CD-RISC2) | Post-pandemic participants showed higher stress and lower resilience, high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to a pre-pandemic normative sample. Women with an infant admitted to a NICU had higher stress. High income, full-time employment, and partnered relationships lowered stress. Lower stress increased mastery and resilience. Non-white women showed higher stress and lower resilience | Postpartum women are susceptible to stress, depression, and anxiety |

| Pappa et al[109], 2021 | C-S survey | 464 HCWs: Female 68%, male 32%; 43% nurses, 49% married | Six COVID-19 reference hospitals in Greece, from May 2020 to June 2020 | Levels and risk factors of anxiety (GAD-7), Depression (PHQ-9), traumatic stress (IES-R), burnout (MBI) and fear (NFRS) | 30% moderate/severe depression, 25% anxiety, 33% traumatic stress. 65% of respondents scored moderate-severe on EE, 92% severe on DP, and 51% low-moderate on PA. Predictors: Fear, perceived stress, risk of infection, lack of protective equipment and low social support | Need for immediate organisational and individual interventions to enhance resilience and psychological support for HCWs |

| Meesters et al[110], 2022 | C-S online survey | 25 parents (16 mothers, 9 fathers) of infants at NICU | Data collected at Rotterdam NICU from April to June 2020 | Sociodemographic questions related to stressor (PSS:NICU) and COVID questionnaire | Most important sources of stress were being separated from, not being able to always hold their infant, and other family members not allowed to visit | NICU staff can support psychologically parents during hospital isolation and reduce the effect of restrictive measures |

| Piscitello et al[111], 2022 | LS survey | Of 78 eligible, 33 ICU nurses (42%) completed survey: Female 29 (50.9%), male 28 (49.1) | Data collected November to December 2020 at Rush University | Nurse MD (MMD-HP) | Results pre and post intervention were not statistically different | Further research required to identify interventions that could improve nurses’ MD |

| Sezgin et al[112], 2022 | C-S online survey | 10 ICU nurses: 2 males and 8 females | Data collected by online survey in 10 ICUs of 7 hospitals in İstanbul, Turkey, October to December 2020 using the snowball method to recruit | Followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research; 32-item checklist to identify major themes | ‘Death and fear of death’, ‘impact on family and social lives’, ‘nursing care of COVID-19 patients’, ‘changing perceptions of their own profession: empowerment and dissatisfaction’, and ‘experiences and perceptions of personal protective equipment and other control measures’ are the major themes identified | There is need to improve working conditions and develop nursing standards in ICU |

| Rodriguez-Ruiz et al[113], 2022 | LS online survey | HCW in ICU: 1065 in first time and 1115 in second time | Spanish ICUs in October to December 2019 and September to November 2020 | MD (MMD-HP-SPA) | During the pandemic, nurses reported higher MD levels compared to the prepandemic period. ICU physicians reported significantly higher MD levels than ICU nurses during the prepandemic period, but not during the pandemic period | In Spain, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an increase of MD among ICU HCPs |

| Vlake et al[114], 2022 | LS survey | 89 post COVID patients: Male 63 (70%) and female 26 (39%) | VR efficacy data from Dutch post-ICU patients, June 2020 to February 2021; participants followed-up for 6 consecutive months | Psychological distress (IES-R) and QoL related to anxiety and depression (HADS) | High psychological distress levels in all groups. ICU-VR group showed improved ICU satisfaction with respect to the control group. 81% of patients reported a higher ICU quality, which was linked to virtual reality | ICU-VR is an innovative strategy to enhance satisfaction with ICU and improves ICU ratings aftercare, adding to its perceived quality |

| Fumis et al[115], 2022 | C-S survey | Of 62 ICU physicians, 51 participated: Male 60.8%, female 39.2%; 76% married | Burnout investigated in ICU physicians during the second COVID-19 wave in São Paulo, Brazil, from December 10 to December 23, 2020 | Questionnaire with demographic and occupational variables, and information on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on daily life (insomnia, lack of appetite, irritability, decreased libido, fear of being infected, fear of infecting loved ones, overspending) and MBI | 19 (37.2%) showed high burnout, i.e., 96.1% low PA, 51.0% high DP, and 51.0% high EE. Conflicts between the ICU physicians and other physicians were 50% | ICU staff have high burnout level |

| Levi and Moss[116], 2022 | C-S survey | 10 ICU nurses: 9 females and 1 male; 3 married and 7 single | ICU nurses completed psychological stress survey during the COVID-19 pandemic in south-eastern United States from August to September 2020 | Psychological Stress and PTSD Symptoms (PTSD Checklist), job satisfaction (a Likert-type scale), demographic information | The survey revealed 6 recurring themes: Change in Practice, Emotion, Patient’s Family, Isolation, Job Satisfaction, and Public Reaction. 7 of 10 ICU nurses reported PTSD symptoms; 6 of 10 wanted to quit their jobs | Critical care nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic are highly subjected to PTSD; its early identification may prevent other related health deteriorating problems |

| Righi et al[117], 2022 | C-S survey | 465 long COVID patients: 54% male and 46% female; 51 % hospitalised | Patients > 18 yr with SARS-CoV-2 infection at Verona University Hospital during February 29 to May 2 2020, followed for 9 mo | Duration and predictors of symptom persistence (symptom questionnaire), physical health and psychological distress (K10) | 37% of patients had at least 4 symptoms; 42% had symptom lasting more than 28 d. 19% showed psychological distress after 9 mo. Female and symptom persistence at day 28 were risk factors for psychological distress | Patients with advanced age, ICU stay, and multiple symptoms were more likely to suffer from long-term symptoms, with negative impact on both physical and mental wellbeing |

| Gilmartin et al[118], 2022 | C-S survey | 22 post COVID-19 patients: Male 15 (68%), female 7 (32%) | A prospective cohort study through establishing a PICS follow-up clinic at Tallaght University Hospital in October 2020 for patients who had been admitted to their ICU | PICS investigated by psychological assessment for ICU (IPAT), PTSD (PCL-5), cognitive impairment (MoCA) | IPAT score was 6.6 ± 4.6 with a PCL-5 score of 21.1 ± 17.5 and a MoCA score of 24 ± 8.4, suggestive of mild cognitive impairment | Patients have a high burden of physical and psychologic impairment 6 mo following ICU discharge for post-COVID-19 pneumonia |

| Guttormson et al[119], 2022 | C-S online survey | 485 ICU nurses: Female 430 (88.1%), male 56 (11.5%) | Participants recruited from national United States sample of ICU nurses, through AACCN newsletters and social media during the COVID-19 pandemic, October 2020 to January 2021 | Measure of MD (MMD-HP), burnout (PROQOL-5), PTSD symptoms (TSQ), anxiety, and depression (PHQ-ADS) | Nurses reported moderate-high levels of MD and burnout; 44.6% reported depression symptoms and 31.1% had anxiety symptoms, while 47% of participants showed risk for PTSD | United States ICU nurses had high levels of anxiety and depression and higher risk for PTSD |

| Likhvantsev et al[120], 2022 | C-S survey | Of 403 eligible COVID-19 patients in Russian ICUs (Moscow), 135 participated | Prospective cohort study investigated patients admitted in COVID-19 ICUs, March to June 2020 | QoL (SF-36 questionnaire) | Heparin treatment in the ICU proved to be the only modifiable factor associated with an increase in the physical component of QoL | Heparin treatment enhanced QoL during COVID-19 patient recoveries at ICUs |

| Shirasaki et al[121], 2022 | C-S survey | 54 family members (68.5% female, 31.5% male) of 85 patients (16.7% female, 83.3% male) with COVID-19 admitted to ICU participated | PICS-F was investigated between March 23, 2020, and September 30, 2021, in Japan | PICS-F related to Psychological distress (IES-R), anxiety, and depression (HADS), and PTSD (FS-ICU) | Family members had 24% of anxiety, 26% depression and 4% PTSD | One-third of family members of COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU had symptoms of PICS-F |

| Amiri Gooshki et al[122], 2022 | C-S survey | 152 patients with COVID-19: Male 55 (36.2%), female 97 (63.8%); 98 (64.47%) married | Psychological consequences of COVID-19 were investigated at hospitals in south-eastern Iran in 2020 | Demographic and background information, Depression, Anxiety (DASS-21), psychological distress (IES-R) | 73% of patients showed severe PTSD, 26.3% moderate depression and 26.3% severe anxiety | Higher psychological load is enhanced by ICU admission, divorce, illiteracy, and retirement |

| Omar et al[123], 2022 | C-S survey | 445 HCWs (physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists): 171 ECMO-ICU, 274 non ECMO-ICU; male 239 (53.7%), female 206 (46.3%) | HCWs grouped by ECMO service (ECMO-ICU vs non-ECMO-ICU) and burnout status (burnout vs no burnout), in 8 tertiary-care hospital ICUs in Qatar, January 1 to June 30, 2021 | General and demographic questions, burnout (MBI-HSS) | 288 HCWs reported burnout and 158 did not. PA lower among ECMO-ICU personnel compared with those in a non-ECMO-ICU (42.7% vs 52.6%, P = 0.043) | High burnout in both ECMO-ICU and non-ECMO-ICU personnel |

| Arshadi Bostanabad et al[124], 2022 | C-S online survey | 207 ICU nurses: Male 60 (29%), female 147 (71%); 51.7% married | Psychological empowerment was investigated in Iran, from February 2021 through April 2021 | Psychological empowerment questionnaire, demographic information | Positive relationship between clinical competencies and psychological empowerment (r = 0.55, P < 0.001) and between clinical competencies and work experiences (r = 0.17, P = 0.01) | Clinical competency is linked to nurse health and quality of care |

| Zhang et al[9], 2022 | C-S online survey | Of 3055 eligible PICUs HCWs, 2109 HCWs completed the survey: Female 1793 (85.2%) and male 316 (14.98%); 35.04% doctors and 64.96% nurses; 1456 (69.04%) married | Online survey was administered to HCWs in the paediatric ICUs of 62 hospitals in China on March 26, 2020 | General information, PTSD (IES-R), anxiety and depression (DASS-21) | 970 HCWs (45.99%) reported PTSD symptoms; 39.69% had severe depression, 36.46% anxiety and 17.12% high level of stress. Married HCWs showed higher risk of PTSD than unmarried. PTSD was influenced by marital status, intermediate professional titles and exposure history; while professional titles and going to work during the epidemic were a risk factor for depression | During public health emergencies, HCWs need specialised support |

| Kılıç and Taşgıt[125], 2023 | C-S survey | 93 parents who were not allowed to see their NICU babies as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic: 52 mothers (55.91%) and 41 fathers (44.09%) | Data collected between March and October 2021, in the NICU of a public hospital in Ankara, Turkey | Descriptive questionnaire, anxiety, depression, and stress (DASS-42), and Coping Style (CSS) | Depression subscale was 13.69 ± 8.86, Anxiety subscale 12.11 ± 8.37, and stress subscale 19.09 ± 9.24. CSS “self-confident” scale was 2.71 ± 0.65, “optimistic” 2.57 ± 0.59, “helpless” 2.29 ± 0.62, “submissive coping” 2.25 ± 0.49, and “seeking of social support” 2.38 ± 0.52. Participants who received information about their babies’ condition by nurses had lower mean CSS “helpless” and “submissive” subscale scores than others | For parents of NICU patients need use psychological empowerment programs to help them adopt active coping strategies to deal with challenges in times of crisis |

| Pappa et al[126], 2022 | C-S online survey | 464 self-selected HCWs: 68% female, 32% male; nurses (43%), married (49%) | Online questionnaire sent to ICU HCWs in Greece, from May 2020, to June 2020 | Depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7) and traumatic stress (IES-R) related to burnout (MBI) and level of fear (NFRS) | Depression was 30%, anxiety 0 25% and traumatic stress 33%. Burnout was high: 65% of HCWs scored moderate-severe on EE, 92% severe on DP and 1% low-moderate on PA | Need for interventions to enhance resilience and support wellbeing in pandemic |

| Vranas et al[127], 2022 | C-S survey | Of 36 eligible intensivists, 33 participated: Female 12 (36%), male 21 (64%) | Semi-structured interviews conducted on ICUs of six United states between August and November 2020 | Four S (space, staff, stuff, and system) semi-structured interview, related to MD, Burnout and Fear of Becoming Infected | Restricted visitor policies and their perceived negative impacts on patients, families, and staff enhanced MD. Burnout symptoms in intensivists were enhanced by experiences with patient death, exhaustion, and perceived lack of support from colleagues and hospitals | COVID-19 pandemic reduced ICU workers’ well-being, increased burnout and MD |

| Voruz et al[128], 2022 | C-S survey | 102 COVID-19 patients: 26 anosognosic, and 76 nosognosic patients | Tests administered by clinical psychologists and questionnaires online to patients at HUG | Neuropsychological battery (TMT, Stroop task, verbal fluency and GREFEX, backward digit span43 and backward Corsi test, Test for Attentional Performance, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure test, BECLA battery, WAIS-IV, QPC, BRIEF-A), psychiatric (ERQ, BDI-II, STAI, API, PTSD Checklist, GMI, DES, PSS, ESS) olfactory (Sniffing Sticks test battery), dyspnoea (self-report questionnaire), and QoL (SF-36) | Patients with anosognosia for memory dysfunction scored significantly lower on objective cognitive and olfactory measures compared with nosognosic patients; but reported significantly more positive subjective assessments of their QoL, psychiatric status, and fatigue. The number of patients exhibiting a lack of consciousness of olfactory deficits was significantly higher in the anosognosic group. Significantly more patients with lack of consciousness of olfactory deficits were in the anosognosic group, as confirmed by connectivity analyses | Cognitive disorders like anosognosia are related to different COVID-19 symptoms |

| Green et al[129], 2023 | LS survey | 24 ICU HCWs: 67% female, 33% male; 79% nurses | At Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC) in Los Angeles, CA, United States, over a 6-wk period from June 2020 to July 2020 | Administered tests were: SAQ, TC, resilience (BRS), burnout (BSI) | Positive feedback paradigm enhanced resiliency and improve attitudes toward a TC | Need to improve TC and resiliency. A messaging interface to exchange mutual positivity can be a simple, low-cost intervention to provide an effective peer-to-peer support system |

| Wozniak et al[130], 2022 | C-S survey | 3461 HCWs. 352 ICU HCWs: Female 23 (66.5%), male 118 (33.5); 242 (68.7%) married. 3109 no-ICU HCWs: Female 2327 (74.9%), male 779 (25.1%); 1973 (63.5%) married | Mental health outcomes and lifestyles change in ICU HCWs and non-ICU HCWs; the study was carried out at HUG and 8 public hospitals in Switzerland, between May to July 2020 | Anxiety (GAD-7), depression (PHQ-9), distress (PDI) and Well-Being (WHO-5) | ICU HCW: 41% showed low well-being, 46% symptoms of anxiety, 46% depression and 22% peritraumatic distress. ICU HCWs scored higher than non-ICU HCWs on all tests (P < 0.01). Working in ICU rather than in other departments, being a woman, the fear of catching and transmitting COVID-19, anxiety of working with COVID-19 patients, work overload, eating and sleeping disorders can enhance worse mental health outcomes | High prevalence of anxiety, depression, peritraumatic distress and low well-being during the first COVID-19 wave among HCWs, especially ICU HCWs |

| Tariku et al[131], 2022 | C-S survey | 402 of 423 eligible participants, responded to survey: Male 233 (58.0%), female 169 (42.0%); 137 (34.1%) married | HCWs mental disease was investigate in Ethiopia, during the coronavirus disease 2019 | Survey assessing the presence of common mental disorders (SRQ-20) | 22.6% of mental disorders in HCWs. Being female, married, having had direct contact with COVID-19 patients, working in COVID-19 treatment centres and ICU, having any symptoms of COVID-19, and poor social support were a risk factor for mental disorders in HCWs | On-fourth to one-fifth of Ethiopian HCWs have a mental disorder during COVID-19 pandemic |

| Wang et al[132], 2021 | C-S telephone survey | Of 267 eligible patients, 199 COVID-19 patients participated in the survey; male 93 (46.7%), and female 106 (53.3%); age 42.72 ± 17.53; 163 ± 81.9 married | PTSD symptoms in COVID-19 survivors investigated with telephone survey 6 mo after hospital discharge in 5 hospitals of 5 Chinese cities, August to September 2020 | Somatic symptoms after discharge (PHQ-15), PTSD (PTSD-8) | 7% of participants having PTSD; socio-demographic status, hospitalization experiences, post-hospitalization experiences, and psychological status enhanced PTSD symptom | Effects of COVID-19 on survivors can also involve psychological aspects and last for many months after recovery |

| Moll et al[133], 2022 | LS survey | Pre-pandemic survey, 1233 HCWs, of which 572 responded (46.5%): Female 408 (71.3%), male 127 (24.9%). Pandemic survey: Of 1422 clinicians, 710 (49.9%) responded to survey; female 529 (74.5%), male 146 (20.5%) | Burnout data collected March to May 2017 and June to December 2020, during the pandemic at Emory University, Atlanta (Georgia) | Burnout (MBI) | 46.5% (572 respondents) in 2017 and 49.9% (710 respondents) in 2020 shown higher burnout symptoms. Nurses’ burnout prevalence increased with pandemic from 59% to 69% (P < 0.001), with increased EE and DP, and decreased PA. Other HCWs showed no differences in burnout levels between 2017 and 2020 | Nurses are more at risk for burnout after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Groenveld et al[134], 2022 | LS survey | Of 48 post-COVID-19 patients, 40 completed the survey: Female 68%, male 32%; median age 54 yr | Feasibility of virtual reality exercises at home for post-COVID-19 condition was investigated, between July 2020 and February 2021, in the southeast of the Netherlands | VR platform to reduce stress and anxiety and promote cognitive functioning | 70% of participant report an advertising event during VR, but only 25% recall these events. 75% reports VR as having a positive influence on their recovery | VR physical exercises at home is feasible and safe with good acceptance |

| Lovell et al[135], 2023 | LS online Survey | 240 nursing staff, 8 permanent ICU consultants, 32 rotational registrars, 10 allied health staff members, and a team of 10 administrative and 20 operational support staff members of ICUs | A before-and-after interventional online study was conducted over a 2-yr period, between 2019 and 2021, in a 30-bed level-3 ICU within an Australian metropolitan teaching hospital | PERMA-Profiler, questionnaire to assess overall well-being (1 item), negative emotions (3 items: Sadness, anger, and anxiety), loneliness (1 item), and physical health (3 items) | Well-being scores after the intervention were not statistically different from BL. There are three key categories: Boosting morale and fostering togetherness, supporting staff, and barriers to well-being | Study findings may inform strategies for improving ICU staff members' well-being |

| Sun et al[136], 2022 | C-S online survey | 524 ICU nurses provided 340 valid questionnaires (64.89% actual rate); 313 females, 27 males; 229 (67.35%) married | Online questionnaire sent to ICU nurses of 15 Chinese provinces, December 2020 to January 2021 | Tested calling (BCS) and resilience (BRCS) as related to thriving at work (TWS) and ethical leadership (ELS) | All variables strongly and positively correlated with each other. The high resilience group was closely associated with calling after adjusting for age, gender, marital status, and other factors | Nurses’ resilience underlies their promptness to stick to their duty and calling |

| Chommeloux et al[137], 2023 | LS survey | Of 80 eligible patients, 62 patients supported by ECMO for severe ARDS were included in the study | Psychological disorders of ICU patients assessed at 6 and 12 mo after ECMO onset, March to June 2020 in 7 French ICUs | Anxiety, depression, PTSD, and QoL | Mental health is one of the most impaired domains: 44% of patients had significant anxiety, 42% had symptoms of depression and another 42% were at risk of PTSD, one year after admission to an ICU | Despite partial physical recovery one year after COVID-19, psychological function remains impaired |

Admission to the ICU often has significant consequences for patients and their caregivers and family members[20]. It is an event with traumatic potential. In fact, it involves a high stress charge due to invasive and painful procedures, sleep deprivation, unnatural noises and lights, inability to communicate, feeling of helplessness, and especially imminent threat of death[21]. The most frequent negative experiences reported by patients were thirst, loss of control, and noise[22].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients reported increased stress, probably related to the increased preventive and personal protective measures and the increased isolation from family, friends, and caregivers[20]. Indeed, many patients recall traumatic and loneliness elements in their ICU experience and many of them were admitted to the ICU during the pandemic while family members were in critical, sometimes fatal, conditions[23]. ICU admission often renders patients psychologically vulnerable; in fact, patients frequently report high levels of anxiety and depression[24]. Such symptoms may affect treatment plans and outcomes[25]. Psychological distress and psychiatric symptoms should be taken into account to prevent worsening of the quality of life after leaving the ICU[26].

People who are admitted to ICUs may already have or not have psychological distress; ICU admission may worsen pre-existing psychological distressed, expressed as a variety of psychiatric symptoms which resemble post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, excessive worrying, insomnia, and anxiety, or may induce newly developed psychological distress. An Italian study found that ICU admission may be associated with increased depression levels and suicidal ideation in a small, but clinically significant proportion of patients with COVID-19, and may worsen pre-existing depression[27]. A Turkish study showed depression may be mediated by restricted visits to the ICU patient, while anxiety was mediated by ICU admission itself[28]. In this study, ICU admission and visit restriction were independent risk factors; positive polymerase chain reaction for COVID-19 and female gender were associated with both anxiety and depression, as assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale. Another Turkish study examined the quality of sleep using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and depression and anxiety with the HAD in ICU patients with COVID-19; poor sleep quality was associated with depression and longer ICU hospitalisation[29]. The authors concluded that through improving sleep quality would help reducing duration of ICU stay.

Clozapine is a second-generation antipsychotic agent that is reserved to severe, treatment-resistant cases of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder due to potentially life-threatening agranulocytosis. Because of this, it is associated with worse pulmonary outcomes, namely pneumonia[30]. Although the use of second-generation antipsychotics is generally associated with reduced odds of getting a COVID-19 infection[31], it has been suggested that patients on clozapine may be at higher risk of COVID-19 infection[32]. However, ICU patients with COVID-19 on clozapine did not differ for outcome from those receiving other antipsychotics[33].

As previously mentioned, the ICU exposes patients to stressful experiences with potential long-term repercussions. People who overcome a critical phase of illness and ICU admission can develop a post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), a cluster of physical, cognitive, and mental impairments observed after ICU hospitalisation; this shares clinical features with depression, anxiety, and PTSD[34]. The main risk factors for developing PICS can be classified as interventional, environmental, and psychological factors, including treatments such as mechanical ventilation, unfamiliar environment, and severe stress experienced during hospitalisation[26,35].

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the number of patients exposed to risk factors of PICS and who require intensive care and aftercare[20]. Furthermore, a COVID-19 patient in the ICU who develops acute respiratory failure, is likely to be exposed to increased use of sedation and limited physical therapy in addition to mechanical ventilation. Therefore, critically ill COVID-19 patients have high chances of developing PICS[23]. Patients with COVID-19 who were treated in the ICU and survived have higher risk due to visit restriction, prolonged mechanical ventilation, higher sedative exposure, and reduced availability of physical therapy[36], but they are also at risk of developing prolonged cognitive dysfunction[37]. Generally, after ICU hospitalisation, mental health problems are very common and often impact health-related quality of life. These include anxiety, depression, and PTSD, as well as guilt, reduced libido, social isolation, irritability, and low confidence[38].

During the pandemic, PTSD appears to have a high incidence, of about 30%[39], characterised by symptoms such as hypervigilance, avoidant behaviour, and re-living the traumatic experience. In particular, hypervigilance may result in panic responses, irritability, and altered sleep-wake cycle, or in overconfident behaviour or, as in the case of COVID-19 patients, with concern about contagion and re-exposure[23]. Sometimes patients may present with disturbing and intrusive memories related to hospitalisation. Specific stimuli, such as smells, images, and sounds, may also activate memories. In addition, some patients may be inclined to avoid any medical environment after ICU admission[23].

COVID-19 and its complications, long hospital stay, and side effects of medications lead to reduced physical capacity that can affect mood. Recent literature has shown that both patients with COVID-19 and those without have high rates of post-hospitalisation depression[40], as well as anxiety and insomnia[41]. However, ICU patients with COVID-19 and ICU patients without COVID-19 did not differ on psychological distress, i.e., cumulative symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression three months after discharge, thus suggesting not to focus exclusively on COVID-19-positive patients[42].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, another major problem was social stigma[43]. In some cases, patients experienced guilt or shame for passing the disease on to others, with ensuing difficulty in returning to their customary daily lives[23]. Multidisciplinary critical care, in addition to preventing imminent death, lays the foundation for improving patients’ overall long-term survival experience[44].

In general, in patients admitted to the ICU, it is important to consider not only physical health but also mental health. This was especially important in COVID-19 patients, as high mortality and unpredictability had peculiar psychological meanings and consequences[45]. Attention is also due to patients with a previous history of mental disorder, as social isolation and estrangement can make the individual particularly vulnerable to psychopathological breakdown events. For this reason, during the pandemic, healthcare personnel has worked closely with psychologists to monitor the psychological condition of patients[45]. In this study, an in-person psychological intervention aimed at preventing unpleasant outcomes was encouraged in the most severe cases, which can result in aggression, self-injurious behaviour, and suicide attempts. Psychological support, taking care to use individual precautions aiming at reducing the risk of infection, was based on the assessment of the patient’s prior state of mental health (traumas, previous episodes of self-harm, etc.) and his/her social and family environment. It is also important to take into account the potential impact of COVID-19 on the patient’s socio-economic status[45].

In some ICUs, interventions such as music therapy or meditation were performed to mitigate the anxiety and distress of patients[46]. The addition of available technological devices such as TV, laptop, or radio may alleviate the patient’s sense of isolation[46]. Sometimes psychological support for COVID-19 patients in ICU has been conducted remotely, through the use of digital tools. In particular, phones and the internet have proven to be effective in treating psychological issues[45]. Technology has also allowed ICU patients to keep in touch with their relatives, with tablets and mobiles provided for this purpose[46]. As mentioned above, patients may experience psychological sequelae even after discharge from the ICU. Early psychological interventions can support the patient in regaining ordinary daily routine. To treat PTSD, anxiety, worry, and panic reactions the use of cognitive behavioural therapy or metacognitive therapy could be given a trial, as these techniques have shown some efficacy in all these conditions[47,48]. In this framework, psychoeducational interventions are used to teach the patient to manage possible stress reactions[49]. Online support groups led by a psychologist can help COVID-19 survivors to share emotions related to the period experienced in the ICU[23].

Family members of patients admitted to the ICU are at high risk of developing psychological disorders. Anxiety, depression, PTSD, and other trauma-related reactions are the most common. In the literature, this clinical condition is called PICS-family[26,50]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these symptoms can exacerbate due to the isolation family members suffer and the impossibility to get into direct contact with their loved ones. In addition, family members are often positive for COVID-19 and isolated at home, and this generates a sense of helplessness and loneliness in patients[45,51]. Relatives play a fundamental role, especially when the patient is dying because they have to make decisions for him, or to defend his/her interests[50].

For these reasons, it is important to design interventions that help preventing psychological dysfunctions among family members and support them in decision making during this difficult moment. In this frame, the psychologist is responsible for establishing clear criteria, that are shared with all health care professionals, to determine whether and how to intervene[52]. The psychological needs of family members to consider in the development of these interventions are the following: The need to be informed and updated about the medical condition of their loved one, the need to be emotionally supported by receiving reassurance and listening, the need to maintain a connection with the patient, even at a distance, and the need to receive support during the grieving process in case of death of their loved one[53]. In all these situations, it is important not to view as pathological any emotional reactions of family members but to consider them as being normal in the context of the difficult moment they are experiencing[52].

Most interventions aimed at family members used digital tools to reduce the possibility of transmitting COVID-19. Phone and video calls were the preferred tools for addressing relatives’ psychological needs[54,55]. However, in case of a high psychopathological risk, family members were allowed to access the ICU. For instance, in-person visits accompanied by the psychologist were encouraged to preserve the relationship between the patient and his/her relatives. Personal protective equipment was used to protect all those involved[53].

During the pandemic, intensive care workers, exposed to a high workload and high risk of infection, reported states of severe anxiety, insomnia, irritability, anxiety, and fear[56]. For this reason, ICU healthcare professionals also seemed to be at serious risk of developing a burnout syndrome. The main factors associated with this risk include weak communication among staff members as well as organisational difficulties[57].

This highlighted the need to develop interventions aimed at ensuring ICU health care professionals’ well-being and preventing emotional distress. These interventions must be designed on the basis of certain primary needs, i.e., the need to feel safe, the need to belong to a unit group with clear, well-defined, and shared goals, the need to be listened to and, finally, the need to emotionally decompress[53]. The literature has confirmed the need for psychologists and psychological interventions in ICUs even during the pandemic; in fact, the applicability of psychological knowledge and skills to staff well-being before and during the pandemic were shown for example to promote teamwork and group cohesion and also to lead defusing activities[53]. Indeed, group defusing can allow for reframing the meaning of a traumatic event by reducing its emotional impact[58]. Defusing is the process of helping a disaster victim through the use of brief conversation and may help survivors in shifting from a survival mode to focusing on practical steps to reach stability again and to better understand the thoughts and feelings linked to their experience of the disaster[59]. Defusing involves professionals in three stages with different functions. Introduction is the general presentation of the intervention to clarify and engage participants. Exploration is the moment in which traumatic experiences related to working in ICU emerge or are extracted, through the recollection of particular thoughts and emotions. Information aims to normalise stress reactions by providing continuous support, reassurance, and coping strategies to address emotional distress[60]. As the pandemic is still persisting or returning under new forms, rapid, pandemic-specific assessment tools may be needed to allow better evaluation of patients’ stress in the ICU[61].

It may also be useful to set up a room for the ICU healthcare professionals to allow them to offload tensions by promoting physical and psychological decompression[53]. Relaxation techniques showed efficacy in managing stress, preventing burnout, and increasing work motivation, in particular autogenic training[62]. Relaxation techniques during COVID-19 confirmed their effectiveness as procedures apt to improve quality of life, work motivation, burnout and stress perceptions within the emergency department team[63].

Psychological interventions in this field should be considered as preventive and proactive health interventions, rather than as treatments for psychopathological problems, helping individuals to effectively express their own resources. Emergency psychology has offered appropriate techniques to achieve this goal[64]. Summarising, COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of frontline workers’ mental health and the need to support the presence of psychologists in ICUs; in this way, healthcare workers could experience more relief from the many responsibilities that hamper the effectiveness of their work[45].

During COVID-19 pandemic in ICUs, patients’ possibilities to see their relatives were reduced[65]. In this context, digital communication proved to be a very effective tool for facilitating communication despite visitation restrictions[66]. Digital interactions can bring significant benefits in terms of emotional support and communication of information to family members, and also in terms of patient recovery and increased ICU staff moral[22].

Recent studies have mainly explored the impact of digital interventions on family members: COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the possibility to see the patient and directly interfacing with the medical teams to receive clinical updates. In general, allowing family members to use video calls to see their loved ones has proven to be a good way to alleviate the discomfort of physical distance[54]. Other studies show that family members report mixed feelings about video calls with the patient. For example, they wanted the opportunity to see the patient but reported that the images of their loved ones lying down were upsetting. This fact underlines the importance of assessing each individual family for burden and preferences[67].

Regarding communication between family members and the medical team, phone calls were used as a tool to communicate quick information[54]. Video calls, instead, were preferred to align doctors and family members’ perspectives on the patient’s condition. Doctors’ doubts about their capacity to transmit empathy at a distance were denied by family members’ opinions, who reported a sense of closeness when using a telephone or a video, despite the distance[66]. An Italian team developed ten statements and two checklists to enable medical teams to communicate effectively with family members, that could be also used as guidelines[68].

It is appropriate at this point to talk about the barriers limiting the use of digital tools in intensive care. In fact, family members do not always have the necessary skills to access the set video platforms or they not even possess a suitable technological device. Problems with the Wi-Fi connection and, in some cases, lack of time and of specific training in the staff add to the above-mentioned barriers[22].

Several ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic used VR interventions to deal with patients’ psychological symptoms such as anxiety, stress, PTSD, and depression[69]. VR bring the user into a “realistic, immersive multi-sensory environment” through computer-generated visuals[70] and this digital tool proved to be effective in reducing anxiety and pain, by distracting the user and providing a relaxing experience[71]. In the presence of full-blown PTSD, VR can subsequently be used as ‘exposure therapy’; it can promote deep involvement and activation of the user’s traumatic memory of fearful stimuli[72], such as those experienced in an ICU[73]. For this reason, VR exposure therapy turned out to be also one of the most popular game-based digital interventions for the treatment of depression caused by fear[74], although in PTSD patients, it did not reduce the anxiety and did not differentiate from other standard treatments[75].

The use of VR as a therapy for the psychological sequelae of COVID-19 patients has some important advantages. First, it could be helpful for reconstructing the phases the patient experienced during the ICU hospitalisation, so to adjust to unpleasant memories, as proposed in a protocol[76]. Second, it can be used remotely to respect social distance needs. Third, it allows to manage more patients at the same time. However, VR implementation should overcome some barriers. These mainly concern the organization of VR interventions at home and remote support. For this purpose, it is necessary to design a toolkit that is safe, comfortable, and easily accessible[70].

Other possible applications of VR during COVID-19 pandemic in ICU include its use to rapidly upskill healthcare professionals and to reduce perceived interindividual stress[56], but also to improve communication of information about ICU treatment and ICU environment to patients’ relatives (ICU-VR-F)[77].

The present review identified 65 studies targeting COVID-19 in ICUs and the ensuing psychological problems, of which 43 focused on the role of the psychologist in increasing team cohesion, reducing distress of patients, relatives, and staff and preventing or reducing burnout in the latter, and highlighting that during the COVID-19 pandemic the psychologist is playing an increasingly important role within the ICU.

Special psychological needs emerged for the patient and his/her relatives, and also for healthcare professionals. Frequently psychologists acted promptly through interventions aimed at providing psychological support to all involved and facilitating communicative exchanges, despite the restrictions imposed. In this way, the medical team members were relieved of much workload and were free to focus mainly on the medical aspects of the cases inside the ICU[74].

As the coordinated interventions of the medical team and the psychologist has proven to be very effective in patient care and in promoting patient well-being, it is desirable that the presence of the psychologist becomes a structural feature of ICUs and other hospital areas that deal with emergencies. Based on the literature, digital tools were much used in ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic to promote communication between patients, family members, and healthcare professionals[56,77]. The addition of new learning-based approaches, such as deep learning or machine learning[78] may help people overcoming this difficult moment by implementing psychological techniques[79]. Since the risk of contagion is still high, they can still be used - when in-person visitation is not strictly necessary - to make communication easier.

VR is a particular technological tool, which is useful in treating psychological sequelae of ICU inpatients. It is mostly used during the COVID-19 pandemic and can significantly improve the mental health of previously hospitalized patients. For their numerous benefits, digital tools, including VR, should be commonly used in ICUs. For this to be possible, however, it is necessary to overcome the previously outlined limitations and barriers.

We did not include in our review other databases that could have accrued our results. The obtain results used diverse methodologies, leading to heterogeneity which did not allow us to perform sound statistical analyses such as meta-analyses or meta-regressions. We did not include specific distinctions regarding the target audience (geriatric patients, neonatal ICUs, or patients with disabilities), so we collected all studies independently from methodology. As a result, we cannot make generalizations regarding the efficacy or effectiveness of the mentioned interventions. Some of these interventions could be modified or adapted according to patients’ needs.

In this review, we analysed the role of the psychologist in the ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the interventions with patients, family members, and healthcare professionals. We chose a narrative review of the literature because currently there is dearth of studies focusing on the psychologist’s work in ICUs during the public health emergency represented by COVID-19. This fact, and the fact that the methodologies of the studies we were able to gather are heterogeneous, make the field not meta-analysable. Since the COVID-19 pandemic is not still over, we need further studies to support the standpoint that psychological support in the ICU is fundamental.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) upset intensive care unit (ICU) function, increasing risk for psychological distress during and after hospitalisation. This paved the way for psychological interventions to support patients in ICUs.

To alleviate the increased workload and burden of ICU staff through psychological interventions.

We carried out a systematic review of the psychological issues raised in ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic which concerned patients, their relatives, and the ICU staff (physicians, nurses, and auxiliary staff) as well as of the possible psychological treatments that could improve psychological measures.

Search of PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov databases, establishing inclusion/exclusion criteria and deciding eligibility through Delphi rounds among involved researchers.

We found 65 eligible articles, which summarised. Results point to increased perceived stress and psychological distress in staff, patients and their relatives. Some psychological interventions hold promise.