Published online Dec 19, 2023. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i12.1079

Peer-review started: October 8, 2023

First decision: October 24, 2023

Revised: November 2, 2023

Accepted: November 9, 2023

Article in press: November 9, 2023

Published online: December 19, 2023

Processing time: 72 Days and 9.5 Hours

Changes in China's fertility policy have led to a significant increase in older pregnant women. At present, there is a lack of analysis of influencing factors and research on predictive models for postpartum depression (PPD) in older pregnant women.

To analysis the influencing factors and the construction of predictive models for PPD in older pregnant women.

By adopting a cross-sectional survey research design, 239 older pregnant women (≥ 35 years old) who underwent obstetric examinations and gave birth at Suzhou Ninth People's Hospital from February 2022 to July 2023 were selected as the research subjects. When postpartum women of advanced maternal age came to the hospital for follow-up 42 d after birth, the Edinburgh PPD Scale (EPDS) was used to assess the presence of PPD symptoms. The women were divided into a PPD group and a no-PPD group. Two sets of data were collected for analysis, and a prediction model was constructed. The performance of the predictive model was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.

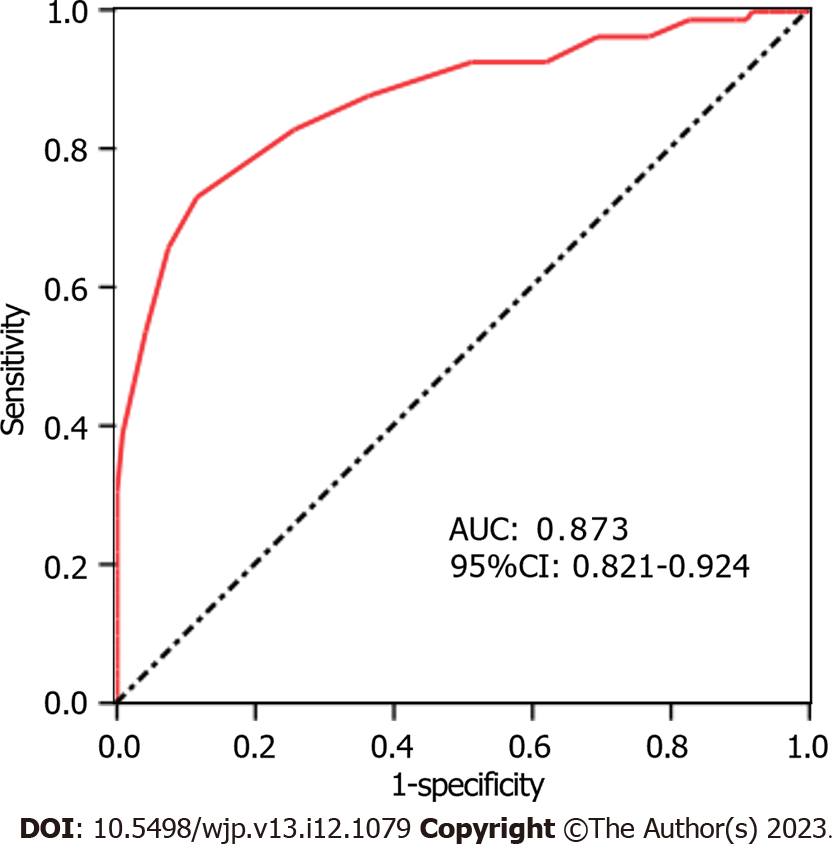

On the 42nd day after delivery, 51 of 239 older pregnant women were evaluated with the EPDS scale and found to have depressive symptoms. The incidence rate was 21.34% (51/239). There were statistically significant differences between the PPD group and the no-PPD group in terms of education level (P = 0.004), family relationships (P = 0.001), pregnancy complications (P = 0.019), and mother–infant separation after birth (P = 0.002). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that a high school education and below, poor family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the separation of the mother and baby after birth were influencing factors for PPD in older pregnant women (P < 0.05). Based on the influencing factors, the following model equation was developed: Logit (P) = 0.729 × education level + 0.942 × family relationship + 1.137 × pregnancy complications + 1.285 × separation of the mother and infant after birth -6.671. The area under the ROC curve of this prediction model was 0.873 (95%CI: 0.821-0.924), the sensitivity was 0.871, and the specificity was 0.815. The deviation between the value predicted by the model and the actual value through the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was not statistically significant (χ2 = 2.749, P = 0.638), indicating that the model did not show an overfitting phenomenon.

The risk of PPD among older pregnant women is influenced by educational level, family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the separation of the mother and baby after birth. A prediction model based on these factors can effectively predict the risk of PPD in older pregnant women.

Core Tip: Older pregnant women are more likely to develop postpartum depression (PPD) than younger pregnant women. PPD can harm the physical and mental health of pregnant women, offspring development, and family and social harmony. Here, we investigated the PPD status of 239 older pregnant women. Based on whether the older pregnant women experienced depression 42 d postpartum, we divided them into a PPD group and a no-PPD group. By conducting statistical analysis on two sets of data and constructing a prediction model, we examined the issue of how medical personnel can effectively assess the PPD risk of older pregnant women.

- Citation: Chen L, Shi Y. Analysis of influencing factors and the construction of predictive models for postpartum depression in older pregnant women. World J Psychiatry 2023; 13(12): 1079-1086

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v13/i12/1079.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i12.1079

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a postpartum mental condition characterized by anxiety, irritability, and extreme depression. In severe cases, hallucinations or suicidal tendencies may occur[1]. PPD not only harms the physical and mental health of pregnant women but also has adverse effects on offspring development, families, and society[2]. Related research reports show that the incidence of PPD among younger pregnant women in China is 14.7%. The incidence of PPD in older pregnant women (≥ 35 years old) is as high as 36.9%[3]. There are some recent studies on PPD in pregnant women, but they are all based on analyses of mental illness history, family relationships, and other aspects[4,5]. There is a lack of exploration on pregnancy complications and the separation of mothers and babies after birth. This results in inadequate clinical measures to prevent PPD, and there is a lack of reporting on predictive models. This study combined the overall situation before, during, and after childbirth to understand the influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women and construct a risk prediction model to provide guidance for obstetricians in predicting the risk of PPD in older pregnant women and developing treatment measures.

Adopting a cross-sectional survey research design, 239 older pregnant women (≥ 35 years old) who underwent obstetric examinations and gave birth in our hospital from February 2022 to July 2023 were selected as the research subjects. According to the Edinburgh PPD Scale (EPDS), the presence or absence of PPD symptoms was measured at 42 d postpartum, and the older pregnant women were divided into a PPD group and a no-PPD group. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Suzhou Ninth People's Hospital.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Women with a gestational age ≥ 37 wk at delivery, a single birth, and natural conception; (2) women with normal consciousness and intelligence; (3) women without adverse pregnancy outcomes (stillbirth, abortion, deformity); (4) women who were informed of this study and signed an informed consent form; and (5) women who were evaluated with the EPDS at 42 d postpartum. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Women with comorbid malignant tumors; (2) women with trauma or infection before delivery; (3) women diagnosed with depression during any depression screening during pregnancy (early, middle, late) or the prenatal period (prior to delivery)[6]; and (4) women with past mental illness.

General information: By creating a general data collection form, age, education level, birth history, pregnancy complications (pregnancy-induced hypertension, pregnancy-induced diabetes, etc.), delivery mode, separation of the mother and infant after birth (referring to the newborn needing to be admitted to the neonatal department for treatment after birth), neonatal feeding mode and other information of the older pregnant women were collected.

Family relationships: The Chinese version of the Family Adaptability Cohesion Environment Scale II-CV[7] was used to evaluate the family relationships of the older pregnant women. This scale mainly evaluates intimacy and adaptability. Intimacy refers to the emotional connection between a mother and her family members. Adaptability refers to the ability of a mother to adapt to the different developmental stages of her family and family situation. This scale consists of 30 items. The total score ranges from 30 to 150 points, and items are scored using a 5-point likert-type (1-5 points) scoring method. The higher the score is, the better the family relationship. In this study, a score of ≤ 70 indicates a lack of harmonious family relationships; a score of > 70 indicates a harmonious family relationship.

PPD diagnosis: At each pregnant woman's follow-up visit at our obstetric clinic on the 42nd day postpartum, we evaluated whether she had PPD symptoms using the EPDS. The scale consists of 10 items, and the total score is 30 points. When the EPDS score of an older mother is ≥ 9 points, it indicates the presence of PPD symptoms[8].

Using SPSS 25.0 software for data analysis, the counting data are expressed in terms of the rate and composition ratio [n (%)]. The two groups were compared and subjected to the χ2 test. The influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women were analyzed through multiple logistic regression analysis, and predictive model equations were built based on the influencing factors.

The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the predictive efficiency of the model, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to evaluate whether the prediction model showed an overfitting phenomenon. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

On the 42nd d after delivery, 239 older pregnant women who attended their outpatient follow-up were included, and 51 were found to have depressive symptoms (PPD group) after evaluation with the EPDS. The incidence rate was 21.34% (51/239); 188 women (no-PPD group) had no depressive symptoms. The comparison between the PPD group and the no-PPD group showed statistically significant differences in terms of education level (χ2 = 8.290, P = 0.004), family relationships (χ2 = 10.672, P = 0.001), pregnancy complications (χ2 = 5.520, P = 0.019), and mother–infant separation after birth (χ2 = 9.681, P = 0.002) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | PPD group (n = 51) | No-PPD group (n = 188) | χ2 | P value | ||

| n | Percent | n | Percent | |||

| Age (yr) | 2.145 | 0.143 | ||||

| 35-40 | 40 | 78.4 | 163 | 86.7 | ||

| > 40 | 11 | 21.6 | 25 | 13.3 | ||

| Education level | 8.290 | 0.004 | ||||

| High school and below | 33 | 64.7 | 79 | 42.0 | ||

| College or higher | 18 | 35.3 | 109 | 58.0 | ||

| Family relationships | 10.672 | 0.001 | ||||

| Harmony | 19 | 37.3 | 118 | 62.8 | ||

| Disharmony | 32 | 62.7 | 70 | 37.2 | ||

| Reproductive history | 0.920 | 0.337 | ||||

| Primipara | 14 | 27.5 | 65 | 34.6 | ||

| Multipara | 37 | 72.5 | 123 | 65.4 | ||

| Pregnancy complications | 5.520 | 0.019 | ||||

| Yes | 20 | 39.2 | 43 | 22.9 | ||

| No | 31 | 60.8 | 145 | 77.1 | ||

| Delivery method | 0.045 | 0.832 | ||||

| Spontaneous labor | 22 | 43.1 | 78 | 41.5 | ||

| Cesarean section | 29 | 56.9 | 110 | 58.5 | ||

| Separation of the mother and infant after birth | 9.681 | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 12 | 23.5 | 15 | 8.0 | ||

| No | 39 | 76.5 | 173 | 92.0 | ||

| Feeding methods of newborns | 4.838 | 0.089 | ||||

| Artificial feeding | 11 | 21.6 | 19 | 10.1 | ||

| Mixed feeding | 18 | 35.3 | 79 | 42.0 | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 22 | 43.1 | 90 | 47.9 | ||

The dependent variable was whether the older pregnant women had symptoms of PPD at 42 d postpartum (0 = no; 1 = yes). Features with statistical significance in univariate analysis (education level, family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the separation of the mother and infant after birth) were included as independent variables, and the assigned values are shown in Table 2. After multiple factor logistic regression analysis, it was found that a high school education and below, poor family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the separation of the mother and baby after birth were the influencing factors for PPD in older pregnant women (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Variable | Description of valuation |

| Education level | 0 = college or higher; 1 = high school and below |

| Family relationships | 0 = harmonious; 1 = disharmony |

| Pregnancy complications | 0= no; 1= yes |

| Separation of the mother and infant after birth | 0= no; 1= yes |

| Variable | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| High school and below | 0.729 | 0.279 | 6.827 | 0.009 | 2.073 (1.199-3.582) |

| Incompatible family relationships | 0.942 | 0.349 | 7.285 | 0.007 | 2.565 (1.294-5.083) |

| Pregnancy complications | 1.137 | 0.414 | 7.543 | 0.006 | 3.117 (1.385-7.015) |

| Separation of the mother and infant after birth | 1.285 | 0.416 | 9.541 | 0.002 | 3.615 (1.599-8.166) |

| Constant | -6.671 | 1.884 | 12.538 | < 0.001 |

The prediction model was constructed based on the regression coefficients and constant terms shown in Table 2 to obtain the following equation: Logit (P) = 0.729 × education level (0 = college or higher; 1 = high school and below) + 0.942 × family relationships (0 = harmony; 1 = disharmony) + 1.137 × pregnancy complications (0 = no; 1 = yes) + 1.285 × separation of the mother and infant after birth (0 = no; 1 = yes) -6.671. Using the predicted probability value of the model as the test variable, the state variable was the presence or absence of PPD in the older mothers. ROC curves were drawn to analyze and predict the performance of the model. The AUC area under the ROC curve of the prediction model was 0.873 (95%CI: 0.821-0.924), the sensitivity was 0.871, and the specificity was 0.815, which indicates that the model has good differentiation ability (Figure 1). The deviation between the predicted value of the model and the actual value through the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was not statistically significant (χ2 = 2.749, P = 0.638), indicating that the model showed no overfitting phenomenon.

China's fertility policy is open, which has resulted in a significant increase in the number of older pregnant women[9]. The incidence of PPD among older pregnant women is relatively high. Some influencing factors for the occurrence of PPD in older pregnant women were identified, and a model was constructed to predict the PPD risk of older pregnant women early, help to take early preventive measures, and reduce the incidence of PPD in older pregnant women.

An analysis of the Chinese PPD population showed that the incidence of PPD was highest within 6 wk after delivery (the postpartum period)[10]. This study found that the incidence of PPD in older pregnant women at 42 d postpartum was 21.34%, which is within the scope of literature reports[11,12]. PPD symptoms in older pregnant women may be caused by various factors. This study further found that a high school education and below, poor family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the separation of the mother and baby after birth were all factors affecting PPD in older pregnant women. Some possible reasons are as follows: (1) Studies have shown that pregnant women with low education levels are prone to fear of childbirth[13]. When a mother has the psychological characteristics of fea, poor cognitive integration, a lack of proactive ways to seek help, and is extremely prone to negative emotions, if she cannot find a positive way to alleviate her fear, she may have a low self-evaluation of postpartum care for her newborn, have an increased psychological burden, and develop PPD. Additionally, a low education level and a poor living environment and family economic situation may also affect PPD risk to some extent[14]. The pressure of raising young children is high[15], quality of life is affected[16], and it is easy to generate negative emotions, which triggers PPD symptoms; (2) family relationships play an important role in the family[17]. A woman usually needs care and attention from her mother-in-law after childbirth[18]; differences in cognition between the two generations may result in differences of opinion regarding the care of the newborn and even conflicts. This invisibly causes psychological pressure and burdens for the new mother[19]. As a result, the family environment is not harmonious, which often increases the mental burden on mothers[20]. Severe cases may result in the mother not receiving sufficient family support, thus increasing her risk of PPD occurrence; (3) older pregnant women tend to have diabetes and hypertension during pregnancy[21]. Research shows that, women diagnosed with pregnancy induced hypertension were more likely to have depressive symptoms than their normotensive counterparts[22]. These pregnancy complications not only increase the risk of PPD[23] but also increase the risk of complications such as postpartum infections and bleeding[24]. Studies have shown that puerperal infection events are significantly correlated with PPD[25]. Which increases the risk of PPD and affects the physical recovery of the mother. Therefore, pregnancy complications are an important factor in increasing PPD; and (4) the health status of newborns is a key concern for mothers and their families. Previous studies have shown that infant health is a contributing factor to PPD in postpartum women[26]. This may be due to the combination of other diseases at birth and the need for a newborn to be transferred to a neonatal department for relevant monitoring and treatment[27], increase maternal concerns about the health status of their children, causing psychological storage of certain negative information, aggravate psychological stress, making it easy for mothers to be emotionally affected by these negative information, increase the risk of postpartum PPD. At the same time, when the newborn is complicated with diseases, the family has to bear a large amount of medical expenses and increase the family burden[28], which significantly increases the probability of PPD in the maternal.

The development of a good prediction model lies in screening effective indicators. This study analyzed the influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women through multiple logistic regression analysis and built a prediction model based on influencing factors. After analysis, it was found that the area under the ROC curve of the prediction model was 0.873, which indicated that the model has high predictive performance. Some reasons for this are as follows: The model was tested with independent samples in this article, irrelevant indicators were filtered out, related indicators were included, information complementarity was realized, and the predictive performance of the model was enhanced. The difference between the value predicted by the model and the actual value through the goodness-of-fit test was not statistically significant, indicating that there was no overfitting in the model, which is suitable for clinical promotion and application. Therefore, building a model based on the various influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women can effectively predict PPD risk, providing a new approach for medical personnel to assess high-risk populations early to develop personalized management measures. For example, strengthening psychological counseling and health education for high-risk populations, advising family members to provide material and spiritual support to new mothers, helping mothers relieve stress, guiding mothers and their families in the care of newborns, enhancing maternal feeding confidence, and reducing the incidence of depressive symptoms are some possible management measures.

However, our study still has some limitations: (1) This was a single-center study with a single source of patients, and the representativeness is relatively limited; and (2) the sample size was small, which may lead to biased results. More participants need to be included to validate the conclusion.

The risk of PPD among older pregnant women is closely related to their educational level, family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the admission of newborns to the neonatal department after birth. A PPD risk prediction model for older postpartum women with good discrimination should be constructed.

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a mental illness that can be caused by multiple factors, including the process of physical recovery in the postpartum period, newborn health, psychological stress, etc. The physiological functions of older pregnant women are far inferior to those of younger women. The process of physical recovery in the postpartum period is slow, and the decrease in a mother’s own physiological stress ability makes them more prone to mental and psychological disorders.

Exploring the influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women and constructing predictive models will provide guidance for the clinical evaluation of PPD risk in older pregnant women and the development of relevant measures.

This study aimed to identify the influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women and construct a prediction model based on the influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women.

This study used a cross-sectional survey to investigate the PPD status of older pregnant women in our hospital and collected their data for analysis.

The incidence of PPD in older pregnant women at 42 d postpartum was 21.34%. Among these older pregnant women, a high school education and below, poor family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the separation of the mother and baby after birth were all influencing factors for PPD. A prediction model built based on these factors had high prediction efficiency.

The risk of PPD among older pregnant women is closely related to their educational level, family relationships, pregnancy complications, and the admission of newborns to the neonatal department after birth. Constructing a PPD risk prediction model for older postpartum women based on the above factors can enable medical staff to perform early assessment of PPD risk for older pregnant women.

The influencing factors of PPD in older pregnant women were identified, and a predictive model was constructed based on these influencing factors to determine the risk of PPD in older pregnant women in the future.

| 1. | Gopalan P, Spada ML, Shenai N, Brockman I, Keil M, Livingston S, Moses-Kolko E, Nichols N, O'Toole K, Quinn B, Glance JB. Postpartum Depression-Identifying Risk and Access to Intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24:889-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yim IS, Tanner Stapleton LR, Guardino CM, Hahn-Holbrook J, Dunkel Schetter C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: systematic review and call for integration. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11:99-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lu L, Dongyan J. Research progress on postpartum depression and nursing intervention measures in elderly postpartum women. Nursing Research. 2019;33:269-272. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhao XH, Zhang ZH. Risk factors for postpartum depression: An evidence-based systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zacher Kjeldsen MM, Bricca A, Liu X, Frokjaer VG, Madsen KB, Munk-Olsen T. Family History of Psychiatric Disorders as a Risk Factor for Maternal Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:1004-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stefana A, Langfus JA, Palumbo G, Cena L, Trainini A, Gigantesco A, Mirabella F. Comparing the factor structures and reliabilities of the EPDS and the PHQ-9 for screening antepartum and postpartum depression: a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2023;26:659-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Phillips MR, West CL, Shen Q, Zheng Y. Comparison of schizophrenic patients' families and normal families in China, using Chinese versions of FACES-II and the Family Environment Scales. Fam Process. 1998;37:95-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yu J, Zhang Z, Deng Y, Zhang L, He C, Wu Y, Xu X, Yang J. Risk factors for the development of postpartum depression in individuals who screened positive for antenatal depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang L, Feng L. Application of hysteroscopy in female fertility preservation. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2022;47:1472-1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mu TY, Li YH, Pan HF, Zhang L, Zha DH, Zhang CL, Xu RX. Postpartum depressive mood (PDM) among Chinese women: a meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2019;22:279-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peng S, Lai X, Du Y, Meng L, Gan Y, Zhang X. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in China: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:1096-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu Y, Guo N, Li T, Zhuang W, Jiang H. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Postpartum Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Among Women in Shanghai, China. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:848-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bina R. The impact of cultural factors upon postpartum depression: a literature review. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29:568-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vigod SN, Tarasoff LA, Bryja B, Dennis CL, Yudin MH, Ross LE. Relation between place of residence and postpartum depression. CMAJ. 2013;185:1129-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tebeka S, Le Strat Y, De Premorel Higgons A, Benachi A, Dommergues M, Kayem G, Lepercq J, Luton D, Mandelbrot L, Ville Y, Ramoz N, Tezenas du Montcel S; IGEDEPP Groups, Mullaert J, Dubertret C. Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression and environmental factors: The IGEDEPP cohort. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;138:366-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Matsumura K, Hamazaki K, Tsuchida A, Kasamatsu H, Inadera H; Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) Group. Education level and risk of postpartum depression: results from the Japan Environment and Children's Study (JECS). BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shi P, Ren H, Li H, Dai Q. Maternal depression and suicide at immediate prenatal and early postpartum periods and psychosocial risk factors. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:298-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chung EO, Hagaman A, Bibi A, Frost A, Haight SC, Sikander S, Maselko J. Mother-in-law childcare and perinatal depression in rural Pakistan. Womens Health (Lond). 2022;18:17455057221141288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peng K, Zhou L, Liu X, Ouyang M, Gong J, Wang Y, Shi Y, Chen J, Li Y, Sun M, Lin W, Yuan S, Wu B, Si L. Who is the main caregiver of the mother during the doing-the-month: is there an association with postpartum depression? BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Guan Z, Wang Y, Hu X, Chen J, Qin C, Tang S, Sun M. Postpartum depression and family function in Chinese women within 1 year after childbirth: A cross-sectional study. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44:633-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pinheiro RL, Areia AL, Mota Pinto A, Donato H. Advanced Maternal Age: Adverse Outcomes of Pregnancy, A Meta-Analysis. Acta Med Port. 2019;32:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Strapasson MR, Ferreira CF, Ramos JGL. Associations between postpartum depression and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:367-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu X, Wang S, Wang G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:2665-2677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 71.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Malmir M, Boroojerdi NA, Masoumi SZ, Parsa P. Factors Affecting Postpartum Infection: A Systematic Review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2022;22:e291121198367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Moraes EV, Toledo OR, David FL, Godoi BN, Monteiro KA, Deluqui TC, Teixeira TW, Carvalho AL, Avelino MM. Implications of the clinical gestational diagnosis of ZIKV infection in the manifestation of symptoms of postpartum depression: a case-control study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dragomir C, Popescu R, Jurca MA, Laza R, Ivan Florian R, Dragomir I, Negrea R, Craina M, Dehelean CA. Postpartum Maternal Emotional Disorders and the Physical Health of Mother and Child. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:2927-2940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shovers SM, Bachman SS, Popek L, Turchi RM. Maternal postpartum depression: risk factors, impacts, and interventions for the NICU and beyond. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021;33:331-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Brownlee MH. Screening for Postpartum Depression in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2022;22:E102-E110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ahmad B, Pakistan; Delvecchio G, Italy S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX