Published online Oct 19, 2023. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i10.743

Peer-review started: August 1, 2023

First decision: August 16, 2023

Revised: August 28, 2023

Accepted: September 5, 2023

Article in press: September 5, 2023

Published online: October 19, 2023

Processing time: 72 Days and 4 Hours

Considering the limited effectiveness of clinical interventions for knee oste

To clarify the influence of ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention on the psychological status and activities of daily living (ADLs) of patients with KOA.

The research participants were 116 KOA patients admitted to The First Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine between May 2019 and May 2022, including 54 patients receiving routine treatment, care and psychological intervention (control group) and 62 patients additionally treated with ankle flexion and extension exercises (research group). The two groups were comparatively analyzed in terms of psychological status (Self-rating Anxiety/Depression Scale, SDS/SAS), ADLs, knee joint function (Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale), pain (Visual Analog Scale, VAS), fatigue (Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, MFI), and quality of life (QoL; Short-Form 36 Item Health Survey, SF-36).

After evaluation, it was found that the postinterventional SDS, SAS, VAS, and MFI scores in the research group were significantly reduced compared with the baseline (before the intervention) values and those of the control group, while the postinterventional Lysholm, ADL and SF-36 scores were markedly elevated.

Therefore, ankle flexion and extension exercises are highly effective in easing negative psychological status, enhancing ADLs, daily living ability, knee joint function and QoL, and relieving pain and fatigue in KOA patients, thus warranting clinical promotion.

Core Tip: This study explores and verifies the clinical advantages of ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention in knee osteoarthritis from the aspects of negative mood, activities of daily living, knee function, pain, fatigue, and quality of life.

- Citation: Liu Y, Chen R, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Ren JL, Wang CX, Xu YK. Clinical value of ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention in knee osteoarthritis. World J Psychiatry 2023; 13(10): 743-752

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v13/i10/743.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i10.743

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a chronic, inflammatory and degenerative joint disease that predominates in middle-aged and elderly women and is pathologically characterized by cartilage degeneration and bone overgrowth (osteophyte and subchondral thickening)[1-3]. KOA patients suffer from joint pain, swelling, stiffness, deformity, and dysfunction, which not only negatively affect patients' activities of daily living (ADLs) to varying degrees but also cause psychological distress to patients, affecting their quality of life (QoL); hence, it is also paramount to intervene in patients psychologically[4,5]. An in-depth analysis of the causes of KOA revealed that abnormal joint loads such as excessive exercise and past sprains, mechanical injuries, age, obesity, diet and genetic factors are factors that increase the risk of developing KOA[6]. According to epidemiological data, KOA is one of the important causes of lower-limb disability in the elderly population and may affect 40% of men and 47% of women, with an incidence of 60% among middle-aged and elderly individuals[7,8]. The pathogenesis of KOA is complicated. Although many attempts have been made to suppress the course of KOA, it is still necessary to continue to explore suitable and effective treatment strategies to improve the condition of KOA patients.

There are many clinical treatment options for KOA, including weight loss, exercise, painkillers, intra-articular hyaluronic acid, and joint replacement surgery[9]. Weight loss is mainly applicable to obese patients, while analgesics, intra-articular hyaluronic acid, and joint replacement surgery carry certain medication or surgical risks, especially for elderly patients with serious diseases[10]. Therefore, this study included an in-depth exploration of therapeutic strategies for KOA patients from the perspective of exercise. Exercise therapy, as a lifestyle intervention, mainly strengthens blood circulation by regulating venous reflux and congestion, thus increasing joint range of motion and muscle strength while positively influencing joint stability[11,12]. Ankle flexion and extension exercise is an exercise mode mainly based on ankle plantar flexion and ankle dorsiflexion, which has a positive effect on lower-limb blood circulation and muscle strength[13]. A report suggests that passive ankle flexion and extension exercises in elderly KOA patients can significantly resolve symptoms and pain with a certain degree of safety, suggesting the clinical application potential of this exercise program.

Considering that there are few studies on the clinical application of ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention in KOA, this study evaluated the potential clinical value of these interventions from the aspects of psychology and ADLs.

The study population comprised 116 KOA patients admitted to The First Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine between May 2019 and May 2022, including 54 patients receiving routine treatment and nursing (control group) and 62 patients additionally given ankle flexion and extension exercises (research group). The two patient groups did not differ much in baseline data and had clinical comparability (P > 0.05).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: in accordance with the diagnostic criteria for KOA[14]; primary disease; intermittent joint narrowing, subchondral osteosclerosis, or cystic degeneration shown by radiographs; complete medical records; normal comprehension and expression ability; and high compliance.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: history of knee joint trauma or surgery; knee joint redness, swelling, heat pain, and obvious limitation of motion; complications with other serious chronic diseases that are not suitable for routine functional exercise; and cardio-cerebrovascular diseases, malignant tumors, or coagulation dysfunction.

The control group received routine therapy. A comfortable hospitalization environment was provided for patients. Meanwhile, nursing staff patiently addressed the doubts and concerns of patients and their families and provided vital sign monitoring, dietary guidance, psychological care, health education, nursing-patient interaction, and local massage. In addition, patients were informed of matters to be noted during the convalescence period to prevent and control the occurrence of complications and were assisted in relieving limb symptoms and reducing the pain of the primary lesion as much as possible. The psychological intervention is described below. First, relevant health education was carried out, and the etiology of KOA and the mechanism and purpose of the treatment were explained to patients in plain language to enhance their disease awareness and better understand the treatment methods, thus improving their cooperation as much as possible. Second, by enumerating patients who experienced positive outcomes (patients who experienced an ideal curative effect after following the doctor's advice) and patients who experienced negative outcomes (patients who experienced unsatisfactory curative effects due to noncompliance with the doctor's advice), the patients developed a greater realization of the importance and necessity of following the doctor's advice. Third, during the treatment, medical staff actively asked patients about their treatment feelings to optimize patients’ treatment experience and find potential problems in time to give reasonable suggestions. Patients' psychological status was also considered, and psychological counseling was given in a timely manner. Moreover, the hospital provided a quiet and comfortable environment for patients so that they could take the initiative to receive diagnosis and treatment.

In addition to the measures implemented in the control group, the research group was also treated with cognitive education and ankle flexion and extension exercises. The cognitive education intervention is described below. Health and KOA-related cognitive education was conducted through multimedia lectures, mainly teaching the characteristics, functions, pathological mechanisms, risk factors and treatment methods of KOA, so that patients could understand the therapeutic value and mechanism of exercise therapy in KOA. Ankle flexion and extension exercise methods were as follows: (1) Supine ankle flexion and extension: The patient took the supine position with toes pointing to the ceiling as the starting position; the ankles were flexed and kept in that position for 10 s, followed by ankle dorsolateral extension that was maintained for 10 s before returning to the initial posture. The above exercises were performed for 20 repetitions per set with 5 sets per session and a 1-min break between sets; (2) Ankle flexion and extension in the seated position: The patient sat on the chair, with feet flat on the ground and toes pointing straight ahead; ankle plantar flexion of both feet was performed for 10 s, followed by ankle dorsiflexion for 10 s; finally, the patient returned to the initial posture. The above exercises were performed for 20 repetitions per set with 5 sets per session and a 1-minute rest between sets; and (3) Ankle flexion and extension in the standing position: The patient took a comfortable standing posture with one or both hands placed on the table or wall for support; foot plantar flexion followed by ankle dorsiflexion was performed; finally, the patient returned to the initial posture. The above exercises were performed for 10 repetitions per set with 5 sets per session and a 1-min break between sets. The ankle flexion and extension exercises in these three positions were performed in turn, that is, supine ankle flexion and extension on the first day, seated ankle flexion and extension on the second day, and standing ankle flexion and extension on the third day. Both groups were treated for three months.

Psychological state. We used the Self-rating Depression/Anxiety Scale (SDS/SAS)[15] to evaluate patients' depression and anxiety before and after the intervention. Both scales have 20 items and a score range of 0-80 points, with the scores in direct proportion to the patient's depressive and anxious symptoms.

ADLs. Patients were evaluated before and after the intervention using the ADL Scale[16] for feeding, bathing, dressing, decorating, continence, and toileting domains, with a maximum score of 100. A higher score suggests a more significant improvement in patients’ ADLs.

Knee joint function. Knee joint function assessment was made before and after treatment using the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale[17], with the evaluation contents including pain, swelling, limping, blocking, instability, crouching, and climbing stairs. On a 100-point scale, higher scores are associated with better recovery of knee function.

Degree of pain. Before and after the intervention, patients were also assessed by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS; score range: 0-10)[18] to determine the degree of pain. The score is directly proportional to the degree of pain.

Fatigue. The fatigue of patients before and after the intervention was evaluated by the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI)[19], a tool with a score ranging from 20 to 100 that is positively related to fatigue.

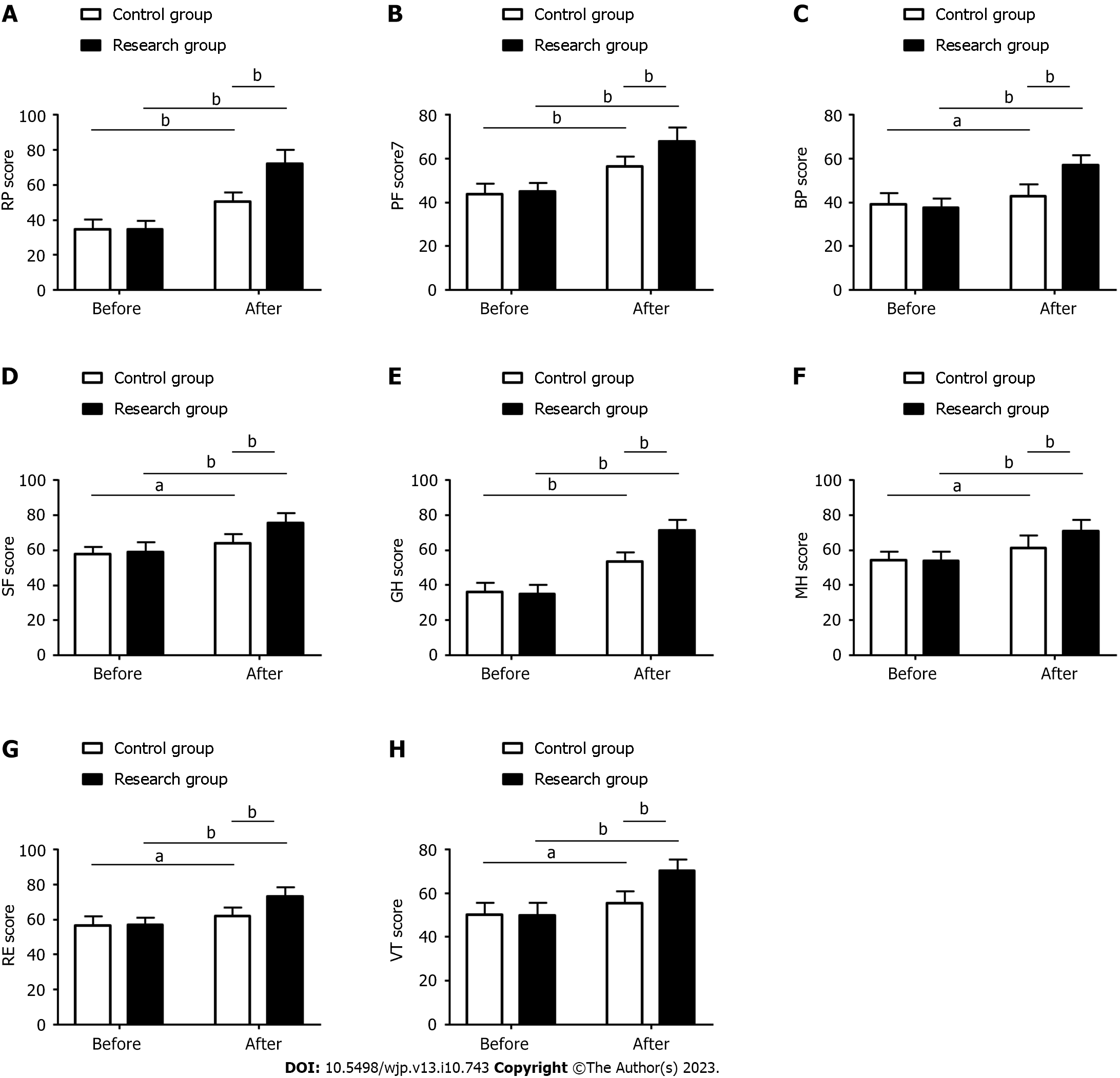

QoL. Finally, we assessed patients’ QoL from eight dimensions [physical functioning (PF); role-physical (RP); bodily pain (BP); social functioning (SF); general health (GH); mental health (MH); role-emotional (RE), and vitality (VT) by referring to the Short-Form 36 Item Health Survey (SF-36)]. Each dimension has a score of 0-10 that is positively correlated with QoL.

The mean ± SEM was used to describe the measurement data, and the independent-samples t-test was used to compare two sets of measurement data. The intergroup comparison of count data expressed by percentages (%) was made by the

Baseline data such as age, sex, course of disease, single knee disease, cause of disease and education level of KOA patients in the two groups were compared and analyzed, and no significant differences were found (P > 0.05). See Table 1.

| Factors | Control group (n = 54) | Research group (n = 62) | χ2/t value | P value |

| Age (yr) | 59.46 ± 6.95 | 58.55 ± 6.82 | 0.711 | 0.479 |

| Sex (male/female) | 25/29 | 27/35 | 0.894 | 0.466 |

| Disease course (yr) | 5.20 ± 2.55 | 5.37 ± 2.67 | 0.349 | 0.728 |

| Single knee disease (yes/no) | 38/16 | 41/21 | 0.813 | 0.269 |

| Cause of illness (excessive exercise/sprain/others) | 25/19/10 | 29/21/12 | 0.406 | 0.705 |

| Education level (junior high school and below/senior high school and above) | 34/20 | 38/24 | 0.404 | 0.725 |

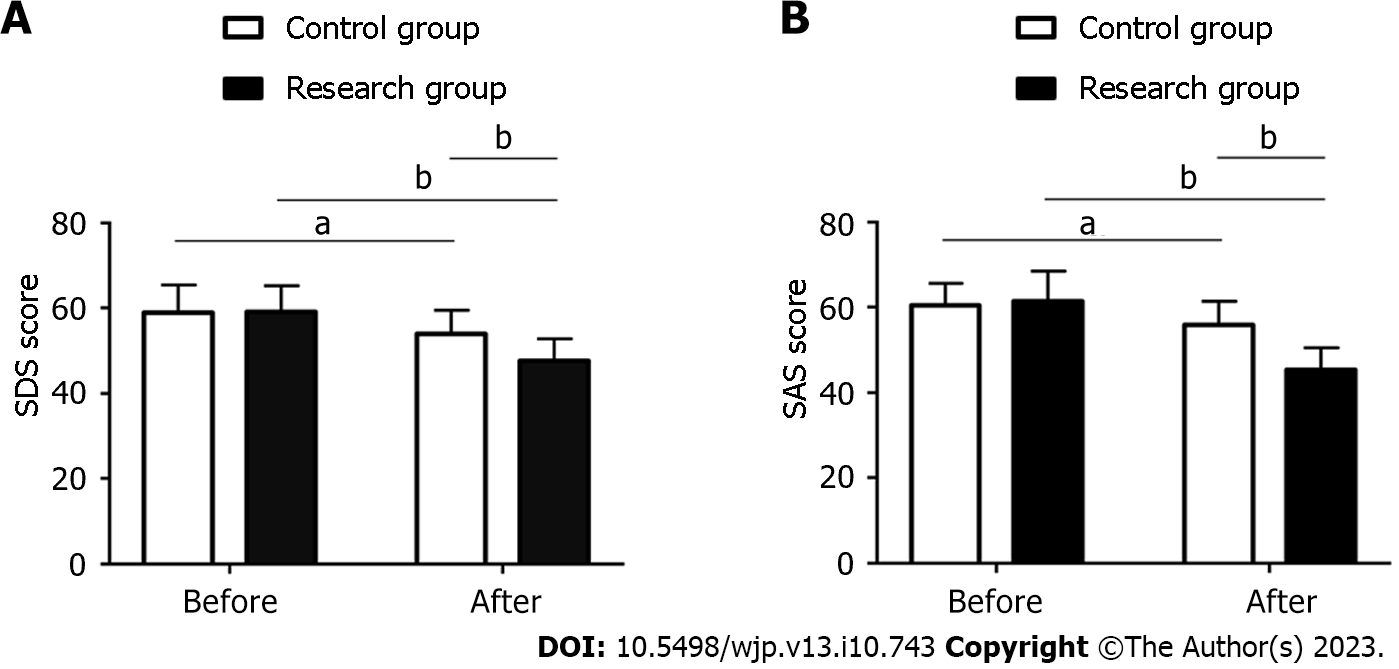

We evaluated patients’ negative psychological state by using the SDS and SAS. The results showed no significant difference in the two scale scores between the research and control groups prior to intervention [SDS: (59.15 ± 6.05) score vs (58.91 ± 6.44) score, SAS: (61.34 ± 7.13) score vs (60.37 ± 5.31) score, P > 0.05]. An obvious reduction in both scales was found in the two groups after the intervention [SDS: (47.60 ± 5.21) score vs (54.02 ± 5.51) score, SAS: (45.32 ± 5.16) score vs (55.83 ± 5.62) score, P < 0.05], especially in the research group (P < 0.05). See Figure 1.

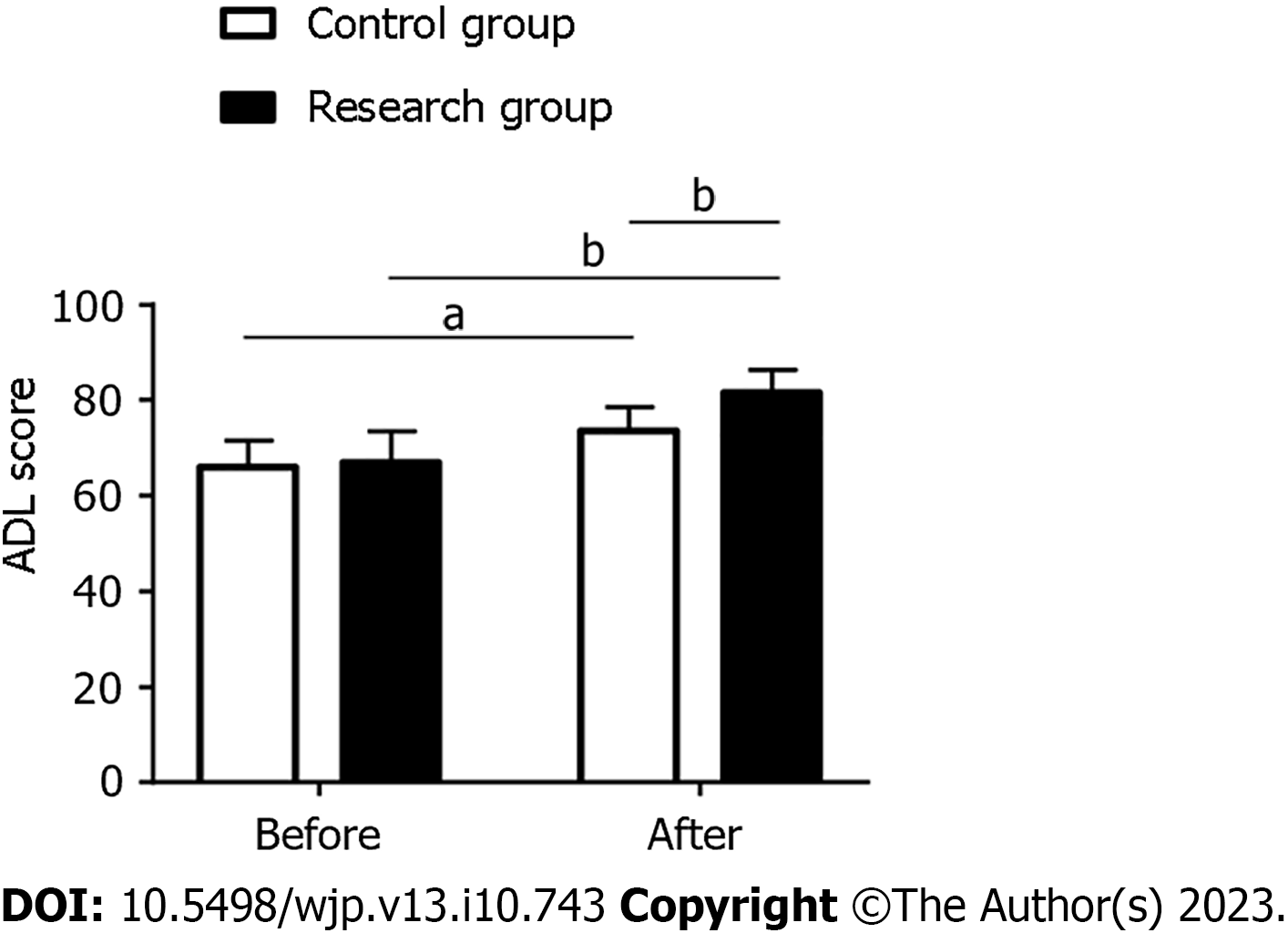

KOA patients’ ADLs were assessed by the ADL scale. The ADL score did not differ markedly between the groups prior to intervention (66.97 ± 6.53) score vs (65.98 ± 5.65) score, P > 0.05), but it was elevated in both groups after the intervention (81.44 ± 4.95) score vs (73.50 ± 5.13) score, P < 0.05), with a higher postinterventional score in the research group (P < 0.05). See Figure 2.

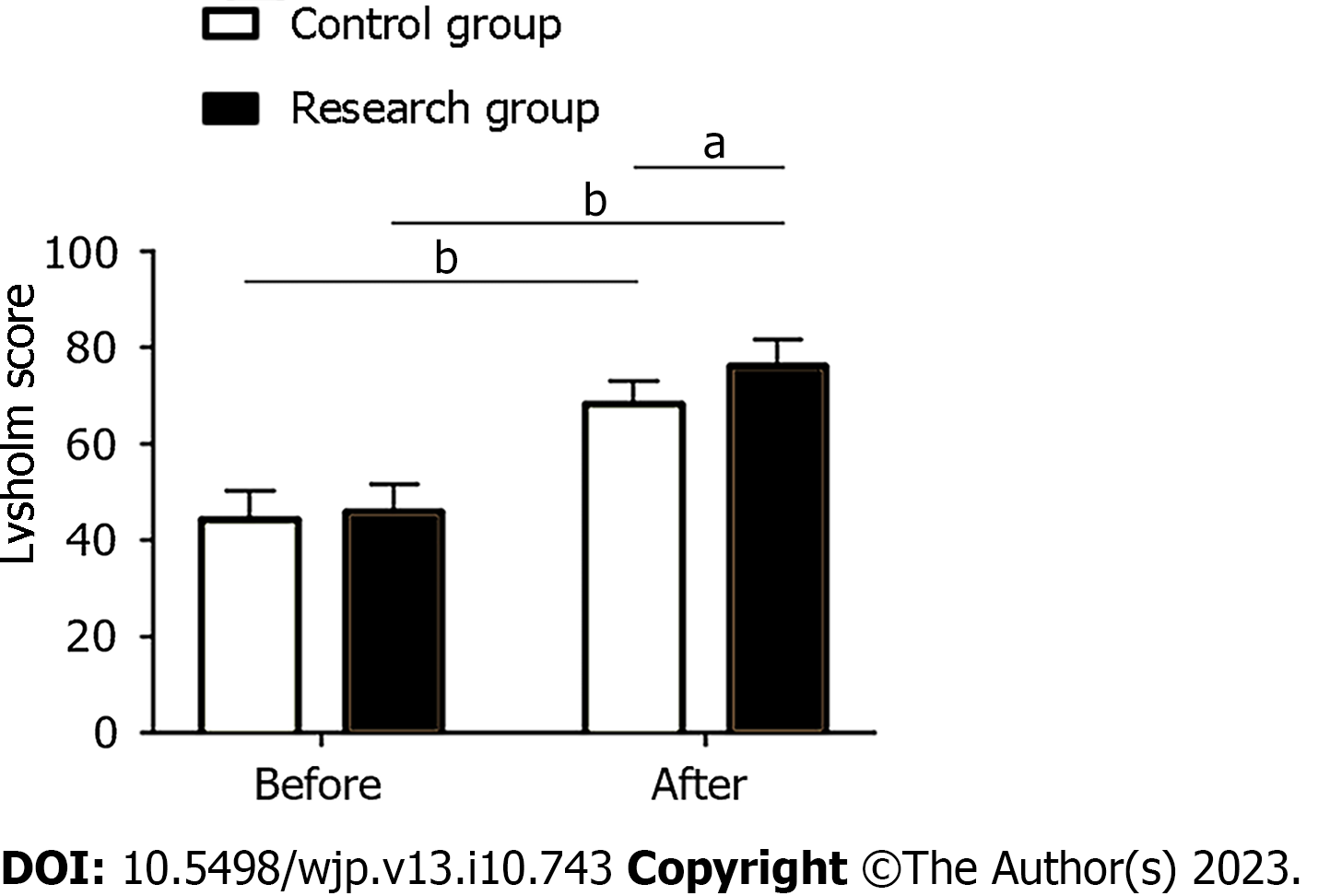

Knee function was assessed in both groups of KOA patients using the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale. The two groups also showed similar Lysholm scores before the intervention (45.89 ± 5.69) score vs (44.43 ± 5.79) score, P > 0.05. An evident elevation in the Lysholm score was found in both arms after the intervention, with an even higher score in the research group (76.40 ± 5.25) score vs (68.39 ± 4.74) score, P < 0.05. See Figure 3.

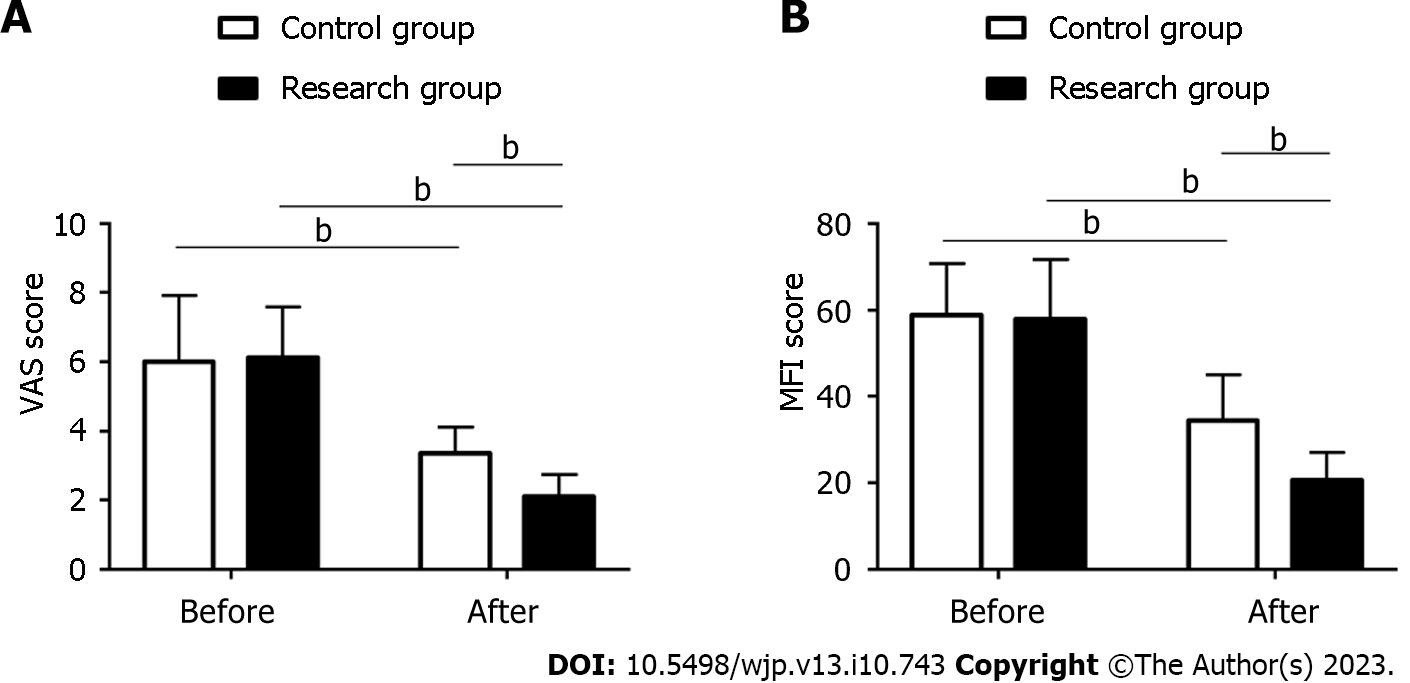

By evaluating the VAS and MFI scores of both groups, the pain and fatigue status of KOA patients were determined. VAS and MFI scores were found to be similar in the two groups before the intervention [VAS: (6.11 ± 1.47) score vs (6.00 ± 1.91) score, MFI: (57.87 ± 13.85) score vs (58.81 ± 11.94) score, P > 0.05], but they were significantly reduced after the intervention, with even lower scores in the research group [VAS: (2.11 ± 0.63) score vs (3.35 ± 0.76) score, MFI: (20.55 ± 6.61) score vs (34.48 ± 10.50) score, P < 0.05]. See Figure 4.

The QoL of KOA patients in both groups was evaluated using the SF-36 scale. The data revealed no significant difference in SF-36 scores between the research and control groups before the intervention (P > 0.05). The SF-36 scores of both arms showed a significant upward trend after the intervention (P < 0.05), with a more significant increase in the research group (P < 0.05). See Figure 5.

KOA, with complex pathological mechanisms and triggers that are not fully understood, has no effective treatment at present[20]. Ankle flexion and extension exercises, as a type of exercise rehabilitation therapy, integrate and apply the knowledge of sports medicine, rehabilitation medicine, biomechanics and modern functional anatomy to provide KOA patients with an evidence-based exercise intervention[21]. In the research of Abbott et al[22], exercise therapy was proven to be beneficial to physical function recovery in KOA patients, suggesting the potential value of ankle flexion and extension exercises in KOA. In another study, exercise therapy was more effective in treating KOA than conventional therapy, contributing to more significant pain reduction and improved function and QoL[23]. Psychological intervention is a measure centered on patients' psychological state and emotional experience, which can improve patients' functional outcomes by eliminating or alleviating their psychological distress[24]. Previous studies have shown that psychological intervention can play a positive role in reducing the severity of KOA symptoms and improving life satisfaction by establishing a positive attitude toward illness[25].

According to the negative psychological state investigation in this study, the research group had markedly reduced SDS and SAS scores after the intervention, which were lower than those of the control group, suggesting that ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention have a good regulatory effect on the negative psychological state of KOA patients. Song et al[26] reported that modified Tai Chi exercises, as a kind of kinesitherapy, can significantly relieve anxiety and depression in elderly female patients with KOA, similar to our findings. Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression in KOA patients have been shown to be related to factors such as high pain levels[27]. In this study, the research group who received ankle flexion and extension exercises experienced a significant reduction in pain levels after the intervention, which may help explain its relieving effect on negative emotions. Furthermore, in the investigation of ADLs, the research group showed a postinterventional ADL score that was evidently higher than the baseline and that of the control group, indicating that ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention are beneficial to significantly improve the ADLs of KOA patients. This may be attributed to the improvement in muscle strength and range of motion in patients after ankle flexion and extension exercises, thus reducing activity limitations in such patients[28]. Subsequently, knee function analysis revealed markedly increased Lysholm scores in the research group that were higher than those in the control group after the intervention, which indicates that ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention are conducive to enhancing the knee joint function of KOA patients. Exercise therapy, such as ankle flexion and extension exercises, has also been reported to alleviate KOA by enhancing muscle strength, restoring neuromotor control and improving the range of joint motion[29]. Later, the analysis of pain and fatigue showed marked reductions in VAS and MFI scores in the research group that were significantly lower than those in the control group, demonstrating that ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention are significantly effective in mitigating pain and fatigue in KOA patients. Peeler et al[30] noted in their study that low-load exercise for KOA patients has significant advantages in improving ADLs and knee joint function, with a potent pain-relieving effect, which can support our research results. In addition, the fatigue of KOA patients is primarily associated with pathological pain and decreased physical function[31]. The alleviation of fatigue in KOA patients may be related to the reduction of pain and improvement of body function by ankle flexion and extension exercises, which agrees with the research results reported by Casilda-López et al[32]. Finally, the QoL assessment showed that the SF-36 scores of the research group increased significantly after the intervention and were markedly higher than those of the control group, indicating that ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention can significantly boost QoL in KOA patients.

Taken together, while resulting in psychological relief and improvement of ADLs, ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention can effectively restore knee joint function and mitigate pain and fatigue in KOA patients, thus playing a positive role in improving the quality of life of patients and warranting clinical promotion.

Given the limited efficacy of clinical intervention in knee osteoarthritis (KOA), it is necessary to continue to explore appropriate and effective treatment strategies to improve the condition of KOA patients.

The pathogenesis of KOA is complex, and exploring effective treatment strategies is of great significance for the prevention and treatment of this disease.

The aim of this study is to clarify the influence of ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with psychological intervention on the psychology and activities of daily living (ADLs) of patients with KOA.

The research participants were 116 KOA patients admitted between May 2019 and May 2022, including 54 cases receiving routine treatment, care and psychological intervention (control group) and 62 cases additionally treated with ankle flexion and extension exercises (research group) on the basis of the control group. The two groups were comparatively analyzed in terms of psychological status (Self-rating Anxiety/Depression Scale, SDS/SAS), ADLs (ADL scale), knee joint function (Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale), pain (Visual Analogue Scale, VAS), fatigue (Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, MFI), and quality of life (QoL; Short-Form 36 Item Health Survey, SF-36).

After evaluation, it was found that the postinterventional SDS, SAS, VAS, and MFI scores in the research group were significantly reduced compared with the baseline (before the intervention) values and those of the control group, while the postinterventional Lysholm, ADL, and SF-36 scores were markedly elevated.

Ankle flexion and extension exercises are highly effective in easing negative psychology, enhancing ADLs, knee joint function and QoL, and relieving pain and fatigue in KOA patients, which is worthy of clinical promotion.

In addition to the positive effect on the negative psychological relief and improvement of ADLs of KOA patients, ankle flexion and extension exercises combined with a psychological intervention can also effectively restore knee joint function, alleviate pain and fatigue, and enhance patients’ quality of life, providing an effective treatment option for KOA patients.

| 1. | Tang S, Chen P, Zhang H, Weng H, Fang Z, Chen C, Peng G, Gao H, Hu K, Chen J, Chen L, Chen X. Comparison of Curative Effect of Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Small Extracellular Vesicles in Treating Osteoarthritis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:8185-8202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:568-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in RCA: 1509] [Article Influence: 301.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Coryell PR, Diekman BO, Loeser RF. Mechanisms and therapeutic implications of cellular senescence in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17:47-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lewinson RT, Stefanyshyn DJ. Wedged Insoles and Gait in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Biomechanical Review. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44:3173-3185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Axford J, Butt A, Heron C, Hammond J, Morgan J, Alavi A, Bolton J, Bland M. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis: use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:1277-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Strath LJ, Jones CD, Philip George A, Lukens SL, Morrison SA, Soleymani T, Locher JL, Gower BA, Sorge RE. The Effect of Low-Carbohydrate and Low-Fat Diets on Pain in Individuals with Knee Osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 2020;21:150-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1145-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 931] [Cited by in RCA: 1144] [Article Influence: 88.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Király M, Kővári E, Hodosi K, Bálint PV, Bender T. The effects of Tiszasüly and Kolop mud pack therapy on knee osteoarthritis: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority controlled study. Int J Biometeorol. 2020;64:943-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hong M, Cheng C, Sun X, Yan Y, Zhang Q, Wang W, Guo W. Efficacy and Safety of Intra-Articular Platelet-Rich Plasma in Osteoarthritis Knee: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:2191926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang D, Song S, Bian Z, Huang Z. Clinical Effect of Catgut Embedding plus Warm Needle Moxibustion on Improving Inflammation and Quality of Life of Knee Osteoarthritis Patients. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:5315619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu W, Wang C, Yu G, Shi B, Wang J. Analysis of the Application Effect of Exercise Rehabilitation Therapy Based on Data Mining in the Prevention and Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:2109528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang L, Chen H, Lu H, Wang Y, Liu C, Dong X, Chen J, Liu N, Yu F, Wan Q, Shang S. The effect of transtheoretical model-lead intervention for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a cluster randomized trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fung KWY, Chow DHK, Shae WC. The clinical effects of mobilization with passive ankle dorsiflexion using a passive ankle dorsiflexion apparatus on older patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2021;34:1007-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Jang S, Lee K, Ju JH. Recent Updates of Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment on Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 70.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang X, Wu P, Luo Y, Tao SY, Li Y, Tang J, Jiang NN, Wang J, Zhao Y, Wang ZY. [Moxibustion for rheumatoid arthritis and its effect on related negative emotions]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2022;42:1221-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ellegaard K, von Bülow C, Røpke A, Bartholdy C, Hansen IS, Rifbjerg-Madsen S, Henriksen M, Wæhrens EE. Hand exercise for women with rheumatoid arthritis and decreased hand function: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Collins NJ, Misra D, Felson DT, Crossley KM, Roos EM. Measures of knee function: International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Evaluation Form, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function Short Form (KOOS-PS), Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADL), Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, Oxford Knee Score (OKS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Activity Rating Scale (ARS), and Tegner Activity Score (TAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11:S208-S228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 909] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | García-Coronado JM, Martínez-Olvera L, Elizondo-Omaña RE, Acosta-Olivo CA, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Simental-Mendía LE, Simental-Mendía M. Effect of collagen supplementation on osteoarthritis symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Int Orthop. 2019;43:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang Z, Pan X, Deng W, Huang Z, Huang Y, Huang X, Zhu Z, Han W, Zheng S, Guo X, Ding C, Li T. Implementation of telemedicine for knee osteoarthritis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xiao CM, Li JJ, Kang Y, Zhuang YC. Follow-up of a Wuqinxi exercise at home programme to reduce pain and improve function for knee osteoarthritis in older people: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2021;50:570-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Holm PM, Schrøder HM, Wernbom M, Skou ST. Low-dose strength training in addition to neuromuscular exercise and education in patients with knee osteoarthritis in secondary care - a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;28:744-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abbott JH, Robertson MC, Chapple C, Pinto D, Wright AA, Leon de la Barra S, Baxter GD, Theis JC, Campbell AJ; MOA Trial team. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial. 1: clinical effectiveness. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:525-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goh SL, Persson MSM, Stocks J, Hou Y, Lin J, Hall MC, Doherty M, Zhang W. Efficacy and potential determinants of exercise therapy in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;62:356-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | das Nair R, Mhizha-Murira JR, Anderson P, Carpenter H, Clarke S, Groves S, Leighton P, Scammell BE, Topcu G, Walsh DA, Lincoln NB. Home-based pre-surgical psychological intervention for knee osteoarthritis (HAPPiKNEES): a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32:777-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hausmann LRM, Youk A, Kwoh CK, Ibrahim SA, Hannon MJ, Weiner DK, Gallagher RM, Parks A. Testing a Positive Psychological Intervention for Osteoarthritis. Pain Med. 2017;18:1908-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Song J, Wei L, Cheng K, Lin Q, Xia P, Wang X, Yang T, Chen B, Ding A, Sun M, Chen A, Li X. The Effect of Modified Tai Chi Exercises on the Physical Function and Quality of Life in Elderly Women With Knee Osteoarthritis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:860762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Klinger R, Stuhlreyer J, Schmitz J, Zöllner C, Roder C, Krug F. [Psychological factors in the context of perioperative knee and joint pain: the role of treatment expectations in pain evolvement]. Schmerz. 2019;33:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lempke L, Wilkinson R, Murray C, Stanek J. The Effectiveness of PNF Versus Static Stretching on Increasing Hip-Flexion Range of Motion. J Sport Rehabil. 2018;27:289-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Woo J, Hong A, Lau E, Lynn H. A randomised controlled trial of Tai Chi and resistance exercise on bone health, muscle strength and balance in community-living elderly people. Age Ageing. 2007;36:262-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Peeler J, Ripat J. The effect of low-load exercise on joint pain, function, and activities of daily living in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2018;25:135-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Snijders GF, van den Ende CH, Fransen J, van Riel PL, Stukstette MJ, Defoort KC, Arts-Sanders MA, van den Hoogen FH, den Broeder AA; Nijmegen OsteoArthritis Collaboration Study Group. Fatigue in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the role of pain and physical function. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1894-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Casilda-López J, Valenza MC, Cabrera-Martos I, Díaz-Pelegrina A, Moreno-Ramírez MP, Valenza-Demet G. Effects of a dance-based aquatic exercise program in obese postmenopausal women with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2017;24:768-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Muller DJ, Canada; Reed JL, Canada S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX