Published online Mar 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i3.483

Peer-review started: August 17, 2021

First decision: October 17, 2021

Revised: October 23, 2021

Accepted: February 19, 2022

Article in press: February 19, 2022

Published online: March 19, 2022

Processing time: 221 Days and 5.5 Hours

Existing literature suggests a positive link between childhood maltreatment (CM) and suicide ideation (SI). Nevertheless, whether social support significantly mediates this association remains unknown.

To investigate whether social support significantly mediates the association between CM and SI.

In this cross-sectional study of 4732 adolescents from southwest China, we intended to discuss the association between CM and multiple types of SI. In addition, the mediation of major types of social support in this association was also investigated. A self-administrated questionnaire was used to collect the data. A series of multivariate logistic regression models were employed to estimate the association between different types of CM, social support, and SI. The possible mediation of social support in the association between CM and SI was assessed using the path model.

Based on the cutoffs for subscales of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, 928 (19.61%), 1269 (26.82%), 595 (12.57%), 2337 (49.39%), and 3067 (64.81%) respo

Our findings suggest that improving parental social support might be effective in preventing suicidal risk related to childhood emotional maltreatment in adolescents.

Core Tip: Childhood maltreatment (CM) is associated with suicide ideation (SI). In the current study, we investigated the mediating role of social support in the association between CM and SI in a large sample (4732) of Chinese children and adolescents. Our results revealed a strong association between emotional CM and SI. In addition, only parental social support has been presented as a significant mediator in the association between emotional maltreatment and SI. The current study highlighted the intervention relevance of parental social support in emotional CM associated with suicidal risk. Rebuilding the parent-child relationship may be a promising way in preventing emotional CM-related suicide.

- Citation: Ahouanse RD, Chang W, Ran HL, Fang D, Che YS, Deng WH, Wang SF, Peng JW, Chen L, Xiao YY. Childhood maltreatment and suicide ideation: A possible mediation of social support. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(3): 483-493

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i3/483.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i3.483

Suicide represents a serious threat worldwide and has become the second leading cause of death among adolescents[1]. The theory of suicidality defines suicidal behavior as a continuous process that begins from suicide ideation (SI) and ends at completed suicide[2]. It has been estimated that more than 1.5 million individuals died of suicide worldwide in 2020[3]. A meta-analysis including 686672 children and adolescents across the world has estimated the lifetime and 1-year suicide prevalence rates in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018 were 18.0% and 14.2%, respectively[4]. In China, according to a large sample cross-sectional study, about 32% of children and adolescents reported SI[5]. SI stands as a relevant indicator of acute suicidal risk because it generally leads to suicidal attempts during the 1st year of the ideation[6,7]. Thus, effective intervention on SI can be a plausible strategy to reduce suicidal risk.

Childhood maltreatment (CM) is an adverse life event that immediately influences the mental health of the children and may compromise their long-term physical and psychological health[7-9]. Normally, CM can be categorized into: physical abuse (PA), emotional abuse (EA), sexual abuse (SA), physical neglect (PN), and emotional neglect (EN)[10]. In China, the estimated prevalence rates of CM were 26.6%, 19.6%, 8.7%, and 26.0% for PA, EA, SA, PN, and EN in 2015[11]. A recent meta-analysis reported a high prevalence rate of CM among Chinese primary and middle school students (PA: 20%, EA: 30%, SA: 12%, PN: 47%, EN: 44%)[12]. It has been reported that CM has a lasting negative influence on the mental health of the victims[13,14]. Children who had been exposed to any kind of CM may present several emotional and behavioral problems such as depression symptoms, anxiety, impulsivity, social isolation, misconduct, aggressivity, delinquency, and hyperactivity[14]. These problems may lead to SI according to the Stress-Diathesis Theory of Suicidality[15]. Additionally, Li et al[16] disclosed that CM history increased the risk of major depressive disorder, an intimate risk factor of SI. From this perspective, a positive connection between CM and SI should exist.

Interpersonal psychological theory of suicidal behavior believes that isolation increases the desire to commit suicide[17]. Perceived social support protects against isolation. Malecki et al[18] defined social support as getting supportive behavior that boosts individual functioning or buffers them from negative outcomes. Social support comes from different sources; therefore, disparities may exist in the associations between different sources of social support and SI. Numerous studies have found that social support from family and friends was negatively associated with SI[19]. However, Hetrick et al[20] found that neither of them showed a significant relationship with suicidal behavior in a clinical sample of young adolescents diagnosed with depressive disorder. More recently, a large cross-sectional study reported that social support from relatives, friends, and parents were all negatively associated with SI among 2899 Chinese rural left-behind children; however, social support from teachers was insignificant[21]. All the existing literature in the field suggests that social support may play a buffering role in SI and suicidal behaviors among youngsters. Nevertheless, controversies remain to be further investigated, especially for different sources of social support.

Moreover, studies have suggested a positive and reciprocal association between CM and social support. On one hand, CM may generate social isolation, behavior disorder, and harmful interaction, which may cause decreased social support[18]. On the other hand, lower social support was also associated with the occurrence of CM[22]. In psychological research, moderation and mediation are two important concepts to understand the association between two variables of study interest. The mediation model assumes that there is a third variable, which sits in the association path between the two variables. In contrast, the moderation model specifies that a third variable modifies the strength of the association between the two variables[23]. Combine all existing evidence together, it is reasonable to suspect that social support may play a mediation role in the association between CM and SI. With this regard, in the current study, we aim to investigate this hypothesis by using a large population-representative sample of Chinese children and adolescents. We put forward the assumption that social support significantly mediates the association between CM and SI. In addition, social support of different sources showed discordant mediation in this association.

We implemented a sampling survey in Kaiyuan, southwestern China Yunnan province between October 19 and November 3, 2020. A two-stage simple random cluster sampling method with probability proportionate to sample size design was used to determine study participants. In the first stage, among all primary, junior high, and senior high schools in Kaiyuan, 19 were randomly selected; in the second stage, based on the required sample size, several classes (4-6) within the chosen school were selected. All eligible students within the chosen class were preliminarily included. Students were further excluded if they were: (1) Aged below 10 years or above 18 years; (2) Reported serious mental or physical illnesses; (3) Had difficulties in hearing or speaking; and (4) Refused to participate. Before the survey, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kunming Medical University.

After written informed consents from the legal guardians were provided, a self-administered questionnaire survey was conducted in each sampling school. The quality of the finished questionnaire was checked on the site immediately by pretrained quality control personnel, who were either graduate students who majored in psychology or public health or health professionals recruited locally. The questionnaire was comprehensive and self-developed and contained the following sections: general characteristics, CM, perceived social support, SI, resilience, sexual harassment behavior, depression, and anxiety, etc. Except for the general characteristics, all the information was measured by using well-established instruments.

CM: The 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) Short form represents one of the best self-report tools that retrospectively screens for five types of CM (PA, EA, SA, PN, EN)[10]. Each item uses a 5-point Likert style rating: never (1 point), occasionally (2 points), sometimes (3 points), frequently (4 points), and always (5 points). The whole questionnaire can be divided into 5 dimensions; each dimension contains five separate questions and measures one specific type of CM. Therefore, the score of each dimension varies from 5 to 25 points, and the total score of CTQ-Short form ranges from 25 to 125. The cutoffs of 8, 9, 6, 8, and 10 for PA, EA, SA, PN, and EA, respectively, were recommended[24]. In this study, we have followed the same cutoffs to dichotomize different types of CM. The Chinese version of CTQ presented a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α: 0.78-0.90) and test-retest reliability (Kappa: 0.79-0.88)[25]. The Cronbach α of CTQ in the current study was 0.84 (bootstrap 95%CI: 0.84-0.85).

Perceived social support: In the current study, we used the Chinese version of Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS) for perceived social support[18]. The 40-item CASSS is a well-validated instrument that measures perceived social support from four sources: parents, teachers, classmates, and close friends. Each source includes 10 items with 5 responses that can be assigned a score from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Consequently, the combined score for every source ranges from 5 to 50 points. In the current study, we dichotomized different sources of social support by using the medians. The Cronbach α of CASSS in the current study was 0.92 (bootstrap 95%CI: 0.92-0.93).

SI: One-week and lifetime SI were assessed using the Chinese version of the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI). BSSI represents one of the best self-report inventories designed to evaluate the intensity of suicide thoughts and intentions. It is composed of 19 items, each graded from 0 to 2 by intensity. A higher total score of BSSI indicates more severe SI[26]. The Cronbach α of the BSSI in the current study was 0.88 (bootstrap 95%CI: 0.87-0.88). One-year SI was determined using a single question: how many times in the past year have you seriously considered ending your life? The responses include: never (0 times), rarely (only once), sometimes (twice), often (3-4 times), and very often (5 times or more). Participants who reported considered ending their own lives at least once were deemed positive.

Depression and anxiety: Depression and anxiety were examined using the Chinese version of The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). PHQ-9 includes 9 questions scored from 0 to 3 based on the intensity of the symptom asked[27]. A recent study recommended a cutoff of 10 or above to screen for major depression whatever the age[28]. In this study, we adopted a threshold of 12 (the median of PHQ-9) to dichotomize study subjects. The Cronbach α of PHQ-9 in the current study was 0.88 (bootstrap 95%CI: 0.88-0.89). For GAD-7, a cutoff score between 7 and 10 can be used to efficiently screen for anxiety[29]. In our study, we used a cutoff of 9 following the median of the combined score. The Cronbach α of GAD-7 in the current study was 0.91 (bootstrap 95%CI: 0.90-0.91).

We performed a descriptive analysis to feature the main characteristics of the participants. The results of the multivariate binary logistic regression models led us to path analysis to determine the direct association between CM and SI, together with their possible indirect association meditated by different sources of social support. Associated factors of SI, childhood abuse, and social support identified from the multivariate logistic regression models were simultaneously incorporated into the hypothesized path model to control for possible confounding. We performed data analysis using the R software (Version 4.0.4). Considering the unequal probability sampling method used in this study, we mainly used the “survey” package to perform descriptive, univariate, and multivariate analyses. Path analysis was executed using the “lavaan” package.

The main characteristics of our study subjects have been summarized in Table 1. Initially, 4858 eligible students were surveyed. Among them, 4732 with complete required information were included in our final analysis. Based on the cutoffs for subscales of CTQ, 928 (19.61%), 1269 (26.82%), 595 (12.57%), 2337 (49.39%), and 3067 (64.81%) were PA, EA, SA, PN and EN victims, respectively. The medians for different dimensions of CASSS were 37 [interquartile range (IQR): 9] for parent’s support, 42 (IQR: 8) for teacher’s support, 37 (IQR: 9) for classmate’s support, and 39 (IQR: 9) for close friend’s support. The prevalence rates of 1-wk, 1-year, and lifetime SI were 26.85% (95%CI: 24.30%-30.00%), 34.99% (95%CI: 30.60%-40.00%), and 55.69% (95%CI: 51.50%-60.00%), respectively.

| Characteristic | mean ± SD1/median (IQR)2 | n (%) | |

| Age | 13.46 ± 1.951 | ||

| Mother’s age | 39.00 ± 5.761 | ||

| Male sex | 2359 (49.85) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Han majority | 1312 (27.73) | ||

| Minorities | 3420 (72.27) | ||

| Grade | |||

| Primary school | 1617 (34.17) | ||

| Junior high school | 2544 (53.76) | ||

| Senior high school | 571 (12.07) | ||

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 1581 (33.41) | ||

| Rural | 3151 (66.59) | ||

| Childhood maltreatment | |||

| Physical abuse (yes) | 928 (19.61) | ||

| Emotional abuse (yes) | 1269 (26.82) | ||

| Sexual abuse (yes) | 595 (12.57) | ||

| Physical neglect (yes) | 2337 (49.39) | ||

| Emotional neglect (yes) | 3067 (64.81) | ||

| Boarding students (yes) | 2373 (50.14) | ||

| Single child (yes) | 1061 (22.42) | ||

| Living situation | |||

| With both parents | 3272 (69.15) | ||

| With single parent | 618 (13.06) | ||

| With others | 1460 (17.79) | ||

| Perceived social support (CASS score) | |||

| Parents | 37 (9)2 | ||

| Teachers | 42 (8)2 | ||

| Classmates | 37 (9)2 | ||

| Close friends | 39 (9)2 | ||

| Suicide ideation (yes) | |||

| 1-wk | 1271 (26.85) | ||

| 1-yr | 1656 (34.99) | ||

| Lifetime | 2639 (55.69) | ||

| Depression (PQH ≥ 12) | 2488 (52.57) | ||

| Anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 9) | 2413 (50.99) | ||

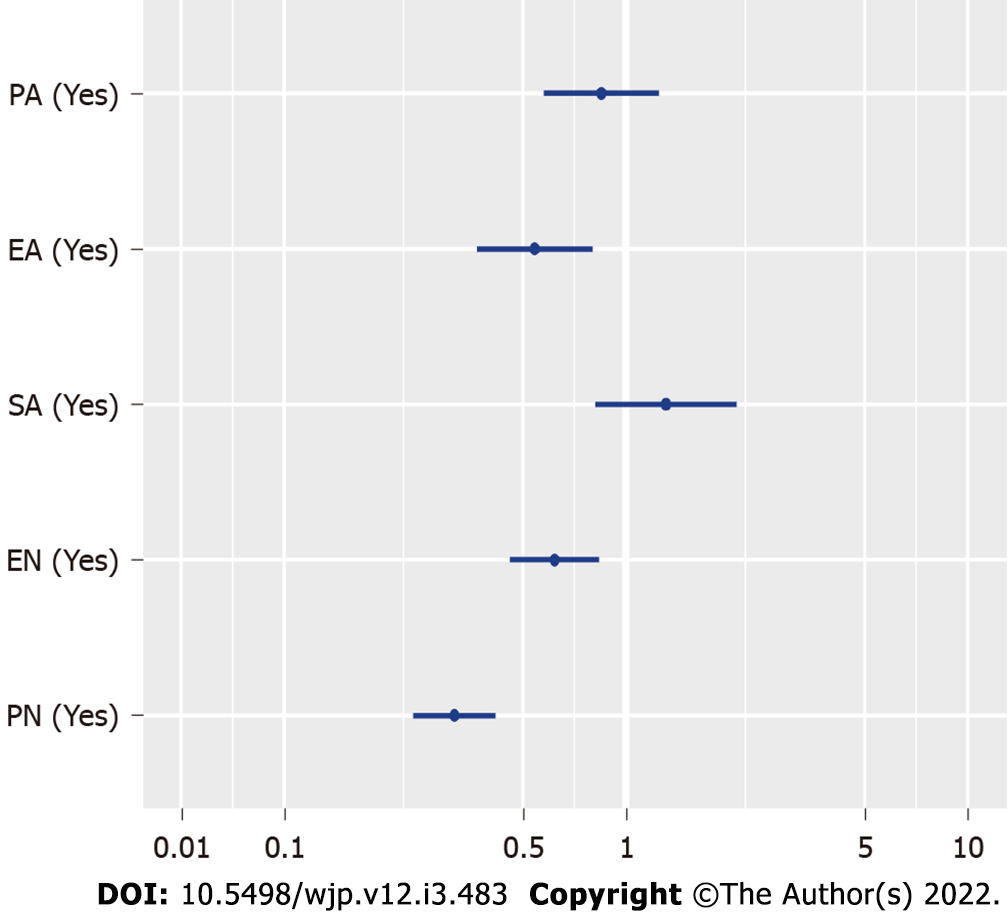

We have used a series of binary univariate logistic regression models to screen for possible influencing factors of different types of SI. Based on the univariate analysis results, a group of multivariate logistic regression was further fitted, and the results were collectively displayed in Table 2. After adjusting for potential covariates, especially depression and anxiety, different types of CM, EA, PN, and EN were consistently associated with elevated odds ratios (ORs) of 1-wk, 1-year, and lifetime SI. For social support of different sources, only the support from parents was inversely associated with SI. Adjusted ORs for 1-wk, 1-year, and lifetime SI were 0.67 (95%CI: 0.55-0.83), 0.64 (95%CI: 0.53-0.77), and 0.63 (95%CI: 0.52-0.77), respectively.

| Covariates | 1-wk SI | 1-yr SI | Lifetime SI | |||

| Multivariate 1 | Multivariate 2 | Multivariate 1 | Multivariate 2 | Multivariate 1 | Multivariate 2 | |

| Sex (Ref: Male): Female | 1.49 (1.31-1.66) | 1.36 (1.20-1.55) | 2.08 (1.75-2.47) | 1.41 (1.12-1.77) | 1.70 (1.42-2.03) | 1.41 (1.12-1.77) |

| Age: + 1 yr | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | 0.87 (0.79-0.96) | 0.95 (0.88-1.03) | 0.87 (0.81-0.95) | ||

| Ethnicity (Ref: Han majority): Minorities | 0.93 (0.76-1.10) | 1.07 (0.92-1.24) | ||||

| Grade (Ref: Primary school) | ||||||

| Junior high School | 1.14 (0.75-1.72) | 1.17 (0.87-1.57) | 1.31 (0.99-1.73) | 1.13 (0.84-1.52) | ||

| Senior high school | 0.83 (0.50-1.38) | 0.80 (0.49-1.29) | 1.18 (0.79-1.75) | 0.74 (0.44-1.25) | ||

| Residence (Ref: Urban): Rural | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | 1.20 (0.99-1.44) | 0.90 (0.73-1.11) | 1.39 (1.10-1.76) | ||

| Boarding students (Ref: No): Yes | 0.70 (0.56-0.88) | 0.72 (0.55-0.92) | ||||

| Single child (Ref: No): Yes | 1.03 (0.92-1.16) | 0.69 (0.54-0.88) | ||||

| Childhood abuse (Ref: No) | ||||||

| PA: Yes | 1.39 (1.17-1.65) | 1.09 (0.86-1.38) | 1.32 (1.04-1.68) | |||

| EA: Yes | 1.99 (1.77-2.26) | 2.79 (2.19-3.56) | 2.08 (1.66-2.60) | |||

| SA: Yes | 1.50 (1.20-1.87) | 1.07 (0.79-1.43) | 1.16 (0.85-1.59) | |||

| PN: Yes | 1.54 (1.33-1.77) | 1.30 (1.06-1.59) | 1.25 (1.07-1.47) | |||

| EN: Yes | 2.28 (1.94-2.67) | 1.63 (1.36-1.97) | 1.47 (1.29-1.68) | |||

| Perceived social support (CASS) | ||||||

| Parent support (Ref: < 37): ≥ 37 | 0.66 (0.55-0.83) | 0.63 (0.52-0.77) | 0.63 (0.52-0.77) | |||

| Teacher support (Ref : < 42): ≥ 42 | 0.94 (0.77-1.12) | 0.97 (0.82-1.14) | 0.97 (0.83-1.14) | |||

| Classmate support (Ref : < 37): ≥ 37 | 0.88 (0.77-1.00) | 0.91 (0.73-1.14) | 0.90 (0.72-1.13) | |||

| Close friend support (Ref : < 39): ≥ 39 | 0.80 (0.69-0.93) | 0.80 (0.64-1.00) | 0.80 (0.64-1.00) | |||

| Depression (Ref PQH < 12): Yes | 1.15 (0.90-1.48) | 1.35 (1.06-1.72) | 2.94 (2.15-4.03) | 1.88 (1.32-2.68) | 2.12 (1.65-2.73) | 1.86 (1.31-2.64) |

| Anxiety (Ref: GAD-7 < 9): Yes | 1.75 (1.46-2.08) | 2.06 (1.72-2.48) | 1.85 (1.35-2.54) | 1.98 (1.62-2.43) | 2.23 (1.84-2.69) | 1.99 (1.61-2.46) |

We further analyzed the adjusted associations between CM and parental social support. For all five types of child abuse, EA, PN, and EN were prominently and inversely related to parental social support (Figure 1).

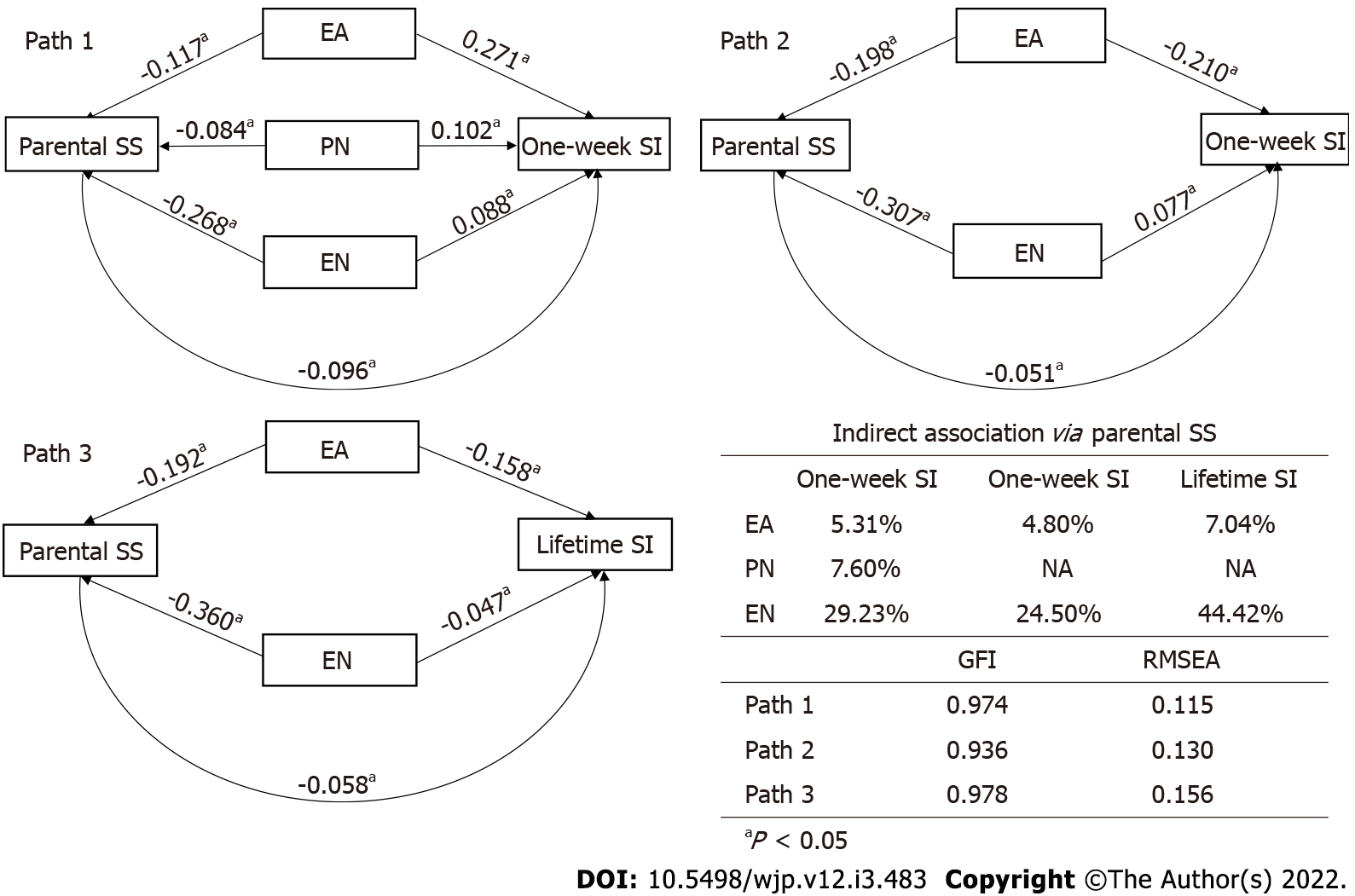

Based on the aforementioned analytical results, we proposed three different path models to illustrate the direct associations between CM and SI, together with their possible indirect associations mediated by parental social support. Standardized path coefficients, together with their statistical test results and model fitting indexes were jointly illustrated in Figure 2. Goodness-of-fit index and root mean square error of approximation indicated ideal model fitting for all three path models. The fitting results revealed that parental social support presented as a significant mediator in the association between emotional maltreatment, both abuse and neglect, and all three types of SI: 1-wk, 1-year, and lifetime. Parental social support mediated 5.31% and 29.23%, 4.80% and 24.50%, and 7.04% and 44.42% of the overall EA-SI and EN-SI associations, respectively.

The current study investigated the association between CM and SI by using a large representative sample of 4732 Chinese children and adolescents. Particularly, we estimated the possible mediation of social support in this association. Our analysis results were in general supportive of the hypotheses: social support could be a prominent mediator in the association between CM and SI. In addition, different sources of social support discordantly mediated the associations between different types of CM and SI. These findings may suggest that to reduce suicidal risk among youngsters who have experienced CM, rebuilding or consolidating social support might be an effective strategy.

We found that among all types of CM, only EN and EA showed a strong association with SI. Previous studies in a Chinese adolescent population also reported a prominent association between EN, EA, and SI[30,31]. EA and EN are related to a range of poor mental health outcomes[32,33]. Although physical and sexual CM have also been linked to SI, a longitudinal study has found that emotional maltreatment was the strongest predictor of SI[34]. Emotional maltreatment has been found to be a strong predictor of internal psychopathology development and may interrupt the psychosocial well-being during children’s growth. Thus, it represents a source of lifetime depression[35]. A meta-analysis revealed that emotional maltreatment was strongly associated with major depression in an adolescent population[36]. These findings highlight the important role of emotional abuse in adolescent suicidal risk.

An important finding of our study is that among all sources of social support only parental social support presented as a significant mediator in the association between emotional maltreatment and SI. This finding is consistent with some previous studies, which have proven that parental support buffered the harmful effect of past stressful events on mental health among adolescents[36,37]. Moreover, some studies have revealed that social support from parents is a principal mediator in the association between depression and SI[37,38]. Parents exert an important impact during adolescence mainly through emotional assistance and positive relationships[39]. Studies have shown a protective effect of parental social support as the pivotal factor in the stress-buffering model[40,41]. Under this situation, supportive parents may protect adolescents against mental disorders even if they have been exposed to a stressful environment. Therefore, intervention measures concentrating on improving or rebuilding the parent-child relationship could be effective in reducing emotional maltreatment associated with suicidal risk among youngsters.

Another interesting finding would be that although parental social support presented as a statistically significant mediator in their associations with SI for both EA and EN, the proportion of parental social support mediation was several folds higher in EN-SI association than in EA-SI association. As the two major types of CM, neglect and abuse have disparate influences on children: in the context of neglect, children could grow up with a lower level of belongingness and acceptance[24], whereas EA victims have experienced an insecure attachment relationship with their parents[42]. Many studies have shown that insecurely attached children are at an elevated risk of mental health problems[43]. In a newly published meta-analysis, the authors concluded that insecure attachment may be a predictor of depression among children and adolescents[44]. Considering the fact that depression is the single strongest risk factor of suicide, it is possible that for emotionally abused adolescents the EA-SI association is in essence the association between depression, which originated from insecure attachment and SI. As adolescent depression is hard to intervene directly, the consolidation of parental social support can only exhibit a very limited effect. Therefore, for adolescents who had experienced childhood emotional maltreatment, when implementing parental social support intervention measures to antagonize suicide risk, priority should be given to neglect victims.

The current study emphasized the role of parental social support in emotional maltreatment associated with suicide risk among Chinese adolescents. Family-based interventions, like family therapy[45] and attachment-based family therapy (ABFT)[46], probably can be used to restore and improve secure parent-child relationships. Prior studies on Chinese adolescents have proven that family therapy can effectively decrease depression symptoms and increase parental social support[47,48]. Meanwhile, the efficacy of attachment-based family therapy in reducing depressive symptoms and SI has also been documented in adolescents[49].

Some limitations of the current study should be noticed. First, our study did not investigate the source of CM in the sample. Second, our analysis was based on cross-sectional data. Therefore, causal inference cannot be reached, and the mediation we identified should be further corroborated by longitudinal studies. Third, all information was collected by self-reporting measures, which are prone to information bias. Finally, the extrapolation of study results to the general adolescent population in China should be made cautiously since our study sample was drawn from a localized region in southwest China.

The current findings provide support for the previous studies regarding the strong relationship between CM and SI. Moreover, a prominent mediation of parental social support has been identified in the association between emotional CM and SI. Our major findings highlight the promising and intervenable role of parental support in antagonizing emotional CM associated with suicide risk. For emotionally maltreated children and adolescents, rebuilding the parent-child relationship might be effective in suicide prevention.

Suicide represents a major public health problem among the child and adolescent populations worldwide. Suicide ideation (SI) is the percussor of suicidal behavior. In China, over 32% of children and adolescents have reported SI. Adverse lifetime events such as childhood maltreatment (CM) increase the risk of SI. Meanwhile, social support protects against SI. Thus, a pathway between CM and SI via social support may exist.

Although the mediation of social support in the association between CM and SI seems plausible, this hypothesis has not been discussed. The motivation of our study is to investigate the mediation role of social support.

To investigate whether social support significantly mediates the association between CM and SI.

A large representative sample of 4732 adolescents from southwest China Yunnan province was surveyed. CM was defined into five types according to the 28-items Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) Short-form: physical abuse (PA), emotional abuse (EA), sexual abuse (SA), physical neglect (PN), and emotional neglect (EN). The Chinese version of the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation, the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire, and the 7-item anxiety scale were used to measure suicide ideation, social support, depression, and anxiety, respectively. We performed logistic regression and path analysis to evaluate the mediation of social support.

The prevalence rates of 1-wk, 1-year, and lifetime SI were 26.85% (95%CI: 24.30%-30.00%), 34.99% (95%CI: 30.60%-40.00%), and 55.69% (95%CI: 51.50%-60.00%), respectively. In addition, based on the cutoffs for subscales of CTQ, 928 (19.61%), 1269 (26.82%), 595 (12.57%), 2337 (49.39%), and 3067 (64.81%) were PA, EA, SA, PN and EN victims. According to the multivariate logistic regression, EA, PN and EN were consistently associated with SI. In addition, parental social support was inversely associated with SI. Following the multivariate analysis results, we performed path analysis. Parent social support presented as a significant mediator in the associations between emotional maltreatment (EA and EN) and SI.

The current study suggests that parental social support may be considered as a potential mediator in the relationship between CM and SI. Intervention to rebuild the parent-child relationship may help to intervene CM-associated suicide risk.

Future longitudinal studies are needed to verify the mediation of parental social support in the association between CM and SI.

| 1. | Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, Vos T, Ferguson J, Mathers CD. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009;374:881-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 748] [Cited by in RCA: 719] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2857] [Cited by in RCA: 2456] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. Suicid. 2002;7:6-8. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lim KS, Wong CH, McIntyre RS, Wang J, Zhang Z, Tran BX, Tan W, Ho CS, Ho RC. Global Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of Suicidal Behavior, Deliberate Self-Harm and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Children and Adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tan L, Xia T, Reece C. Social and individual risk factors for suicide ideation among Chinese children and adolescents: A multilevel analysis. Int J Psychol. 2018;53:117-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Borges G, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Huang Y, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Kovess V, Levinson D, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tomov T, Viana MC, Williams DR. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Klonsky ED, Saffer BY, Bryan CJ. Ideation-to-action theories of suicide: a conceptual and empirical update. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;22:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 51.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Chapman DP, Liu Y, Presley-Cantrell LR, Edwards VJ, Wheaton AG, Perry GS, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and frequent insufficient sleep in 5 U.S. States, 2009: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dhakal S, Niraula S, Sharma NP, Sthapit S, Bennett E, Vaswani A, Pandey R, Kumari V, Lau JY. History of abuse and neglect and their associations with mental health in rescued child labourers in Nepal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53:1199-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3310] [Cited by in RCA: 4292] [Article Influence: 186.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fang X, Fry DA, Ji K, Finkelhor D, Chen J, Lannen P, Dunne MP. The burden of child maltreatment in China: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93:176-85C. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang L, Cheng H, Qu Y, Zhang Y, Cui Q, Zou H. The prevalence of child maltreatment among Chinese primary and middle school students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:1105-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chandan JS, Thomas T, Gokhale KM, Bandyopadhyay S, Taylor J, Nirantharakumar K. The burden of mental ill health associated with childhood maltreatment in the UK, using The Health Improvement Network database: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:926-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:517-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Heeringen K, Mann JJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:63-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li M, D'Arcy C, Meng X. Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychol Med. 2016;46:717-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 518] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, Rudd MD. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:634-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 523] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Malecki CK, Demary MK. Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychol Schools. 2002;39:1-18. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | King CA, Merchant CR. Social and interpersonal factors relating to adolescent suicidality: a review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res. 2008;12:181-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Robinson J, Hall N, Vance A. Predicting suicidal risk in a cohort of depressed children and adolescents. Crisis. 2012;33:13-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Xiao Y, Chen Y, Chang W, Pu Y, Chen X, Guo J, Li Y, Yin F. Perceived social support and suicide ideation in Chinese rural left-behind children: A possible mediating role of depression. J Affect Disord. 2020;261:198-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:706-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 643] [Cited by in RCA: 657] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2003. |

| 24. | Bernstein D, Fink L. Manual for the childhood trauma questionnaire. New York: The Psychological Corporation, 1998. |

| 25. | Han A, Wang G, Xu G, Su P. A self-harm series and its relationship with childhood adversity among adolescents in mainland China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 31355] [Article Influence: 1254.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 632] [Cited by in RCA: 1097] [Article Influence: 156.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1320] [Cited by in RCA: 1250] [Article Influence: 125.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li X, You J, Ren Y, Zhou J, Sun R, Liu X, Leung F. A longitudinal study testing the role of psychache in the association between emotional abuse and suicidal ideation. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75:2284-2292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gong M, Zhang S, Li W, Wang W, Wu R, Guo L, Lu C. Association between Childhood Maltreatment and Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts among Chinese Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kumari V. Emotional abuse and neglect: time to focus on prevention and mental health consequences. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217:597-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Janiri D, De Rossi P, Kotzalidis GD, Girardi P, Koukopoulos AE, Reginaldi D, Dotto F, Manfredi G, Jollant F, Gorwood P, Pompili M, Sani G. Psychopathological characteristics and adverse childhood events are differentially associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal acts in mood disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Miller AB, Jenness JL, Oppenheimer CW, Gottleib AL, Young JF, Hankin BL. Childhood Emotional Maltreatment as a Robust Predictor of Suicidal Ideation: A 3-Year Multi-Wave, Prospective Investigation. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2017;45:105-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | LeMoult J, Humphreys KL, Tracy A, Hoffmeister JA, Ip E, Gotlib IH. Meta-analysis: Exposure to Early Life Stress and Risk for Depression in Childhood and Adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:842-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 411] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 66.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Infurna MR, Reichl C, Parzer P, Schimmenti A, Bifulco A, Kaess M. Associations between depression and specific childhood experiences of abuse and neglect: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ge X, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D. The longitudinal effects of stressful life events on adolescent depression are buffered by parent-child closeness. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:621-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fredrick SS, Demaray MK, Malecki CK, Dorio NB. Can social support buffer the association between depression and suicidal ideation in adolescent boys and girls? Psychol Schools. 2018;55:490-505. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Au AC, Lau S, Lee MT. Suicide ideation and depression: the moderation effects of family cohesion and social self-concept. Adolescence. 2009;44:851-868. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Holahan CJ, Valentiner DP, Moos RH. Parental support and psychological adjustment during the transition to young adulthood in a college sample. J Fam Psychol. 1994;8:215-223. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Hazel NA, Oppenheimer CW, Technow JR, Young JF, Hankin BL. Parent relationship quality buffers against the effect of peer stressors on depressive symptoms from middle childhood to adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:2115-2123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Baer JC, Martinez CD. Child maltreatment and insecure attachment: a meta-analysis. J Rep and Infant Psychol. 2006;24:187-197. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Madigan S, Brumariu LE, Villani V, Atkinson L, Lyons-Ruth K. Representational and questionnaire measures of attachment: A meta-analysis of relations to child internalizing and externalizing problems. Psychol Bull. 2016;142:367-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Spruit A, Goos L, Weenink N, Rodenburg R, Niemeyer H, Stams GJ, Colonnesi C. The Relation Between Attachment and Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2020;23:54-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Pote H, Stratton P, Cottrell D, Shapiro D, Boston P. Systemic family therapy can be manualized: research process and finding. J Fam Therapy. 2003;25:236-262. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Diamond GM. Attachment-based family therapy interventions. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2014;51:15-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Zhang S, Dong J. Improvement of family therapy on the efficacy and social performance of adolescent depression. Zhonghua Xingwei Yixue Yu Naokexue Zazhi. 2013;22:417-439. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 48. | Li J, Wang X, Meng H, Zeng K, Quan F, Liu F. Systemic Family Therapy of Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depression with Epilepsy in Adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13:305-310. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Diamond GS, Kobak RR, Krauthamer Ewing ES, Levy SA, Herres JL, Russon JM, Gallop RJ. A Randomized Controlled Trial: Attachment-Based Family and Nondirective Supportive Treatments for Youth Who Are Suicidal. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kotzalidis GD S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia CL P-Editor: Zhang H