Published online Nov 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i11.1323

Peer-review started: August 1, 2022

First decision: September 4, 2022

Revised: September 16, 2022

Accepted: October 14, 2022

Article in press: October 14, 2022

Published online: November 19, 2022

Processing time: 108 Days and 5.1 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused significant challenges for adolescent mental health.

To survey adolescent students in China to determine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their mental health.

A multicenter cross-sectional comparative investigation was conducted in March 2022. We collected demographic information and survey data related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener scales were used for objective assessment of depression and anxiety.

We collected mental health questionnaires from 3184 students. The investigation demonstrated that adolescents most strongly agreed with the following items: Increased time spent with parents, interference with academic performance, and less travel. Conversely, adolescents most strongly disagreed with the following items: Not having to go to school, feeling an increase in homework, and not socializing with people; 34.6% of adolescents were depressed before COVID-19, of which 1.9% were severely depressed. After COVID-19, 26.3% of adolescents were prone to depression, of which 1.4% were severely depressed. 24.4% of adolescents had anxiety before COVID-19, with severe anxiety accounting for 1.6%. After COVID-19, 23.5% of adolescents were prone to anxiety, of which 1.7% had severe anxiety.

Chinese adolescents in different grades exhibited different psychological characteristics, and their levels of anxiety and depression were improved after the COVID-19 pandemic. Changes in educational management practices since the COVID-19 pandemic may be worth learning from and optimizing in long-term educational planning.

Core Tip: Our investigation found that the Chinese adolescents have different psychological characteristics at different grades, and their levels of anxiety and depression have improved since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The partial educational management practices that have changed since the COVID-19 pandemic may be worth learning from and optimizing long-term educational planning.

- Citation: Huang BW, Guo PH, Liu JZ, Leng SX, Wang L. Investigating adolescent mental health of Chinese students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Multicenter cross-sectional comparative investigation. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(11): 1323-1334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i11/1323.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i11.1323

As of May 13, 2022, China had 1123709 confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), including 7247 cases in Guangdong, 2983 cases in Heilongjiang, and 2675 cases in Beijing (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/). The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically impacted people’s lives, affecting teenagers to the same extent as adults. A survey conducted in Shanghai revealed that some policy changes implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic had a range of impacts on students. Positive factors included an increase in the amount of time spent with parents, and the amount of time spent on personal matters. Negative impacts included not being able to go out to play and not seeing friends or classmates[1].

A meta-analysis of 5153 COVID-19 patients in 31 studies reported that the overall prevalence rates of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders among individuals with COVID-19 were 45%, 47%, and 34%, respectively[2]. Lockdown measures in response to the coronavirus pandemic may have affected university students more than workers, with a survey of 400 people in Italy reporting that approximately one third of the sample exhibited symptoms of depression or anxiety[3]. Thus, students may represent a population that requires special care.

In a survey of 2031 college and graduate students in the United States, 48% reported experiencing depression, 38% reported experiencing anxiety, and 18% reported experiencing suicidal thoughts[4]. A British study of 2850 young people using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) scales also found a significant increase in anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic[5]. A GAD-7 online questionnaire answered by 89588 college students in Hainan, China, found that approximately two-fifths of college students experienced anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic[6]. However, few large-sample multicenter investigations have examined mental health among primary school, junior high school, and senior high school students. No previous study has conducted a detailed subgroup analysis of the changes in the psychological health of samples of students in three different grades before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, we designed an online questionnaire that was administered to respondents in Heilongjiang, Beijing, and Guangdong, three provinces that run from north to south in China. We examined respondents’ basic information, changes in daily habits, and positive and negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on study and life to determine whether the pandemic had worsened or improved depression and anxiety among students, and to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents using a systematic survey with a large sample.

An online cross-sectional comparative survey was designed and conducted during a relatively steady phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the late Spring 2022 semester in Beijing, Guangdong, and Heilongjiang. Our study population comprised primary school students, junior high school students, and senior high school students. An electronic form in the survey was used to obtain informed consent from all participants. We designed, conducted, and reported this survey following the acknowledged guidelines[7]. Respondents were recruited from the teenage population. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, some schools have adopted a combination of online and offline classes. Depending on the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, provinces issued stay-at-home orders if necessary. The survey was published using the online survey platform WenJuanXing (WJX, https://www.wjx.cn/) in March 2022. WJX is a professional online questionnaire survey, examination, evaluation, and voting platform, which focuses on providing users with robust and humanized online questionnaire design, data collection, custom reports, and survey results analysis. The survey was released to more than 30000 students through WeChat groups or websites in several school districts.

The investigation comprised multiple-choice questions and free-text fields for elaboration. The questionnaire consisted of the following four sections.

Demographics: This section included questions regarding participants’ age, gender, and grade classification, which included primary school students, junior high school students, and senior high school students.

Questions about changes in learning and life before and after the COVID-19 pandemic: This section was designed to identify the positive and negative impacts of the pandemic, including the following items: Live with whom, time distribution, positive effects, and negative impacts. Because our preliminary survey results indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had more negative than positive impacts, we divided the negative impacts into learning and life influences.

PHQ-9: The PHQ-9 is a validated and widely used measure of depression severity in mental health care, comprising nine items based on depression symptoms[8]. Respondents reported the frequency of symptoms experienced before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

GAD-7: The GAD-7 is a validated questionnaire for major anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder, consisting of seven items, on the basis of GAD symptoms[9]. Respondents rated the frequency of experiencing these symptoms before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Student’s t-test, χ2 analysis, and Fisher’s test were conducted, and a threshold of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate significant differences. The visualization tool used GraphPad Prism 8 and R 4.1.2.

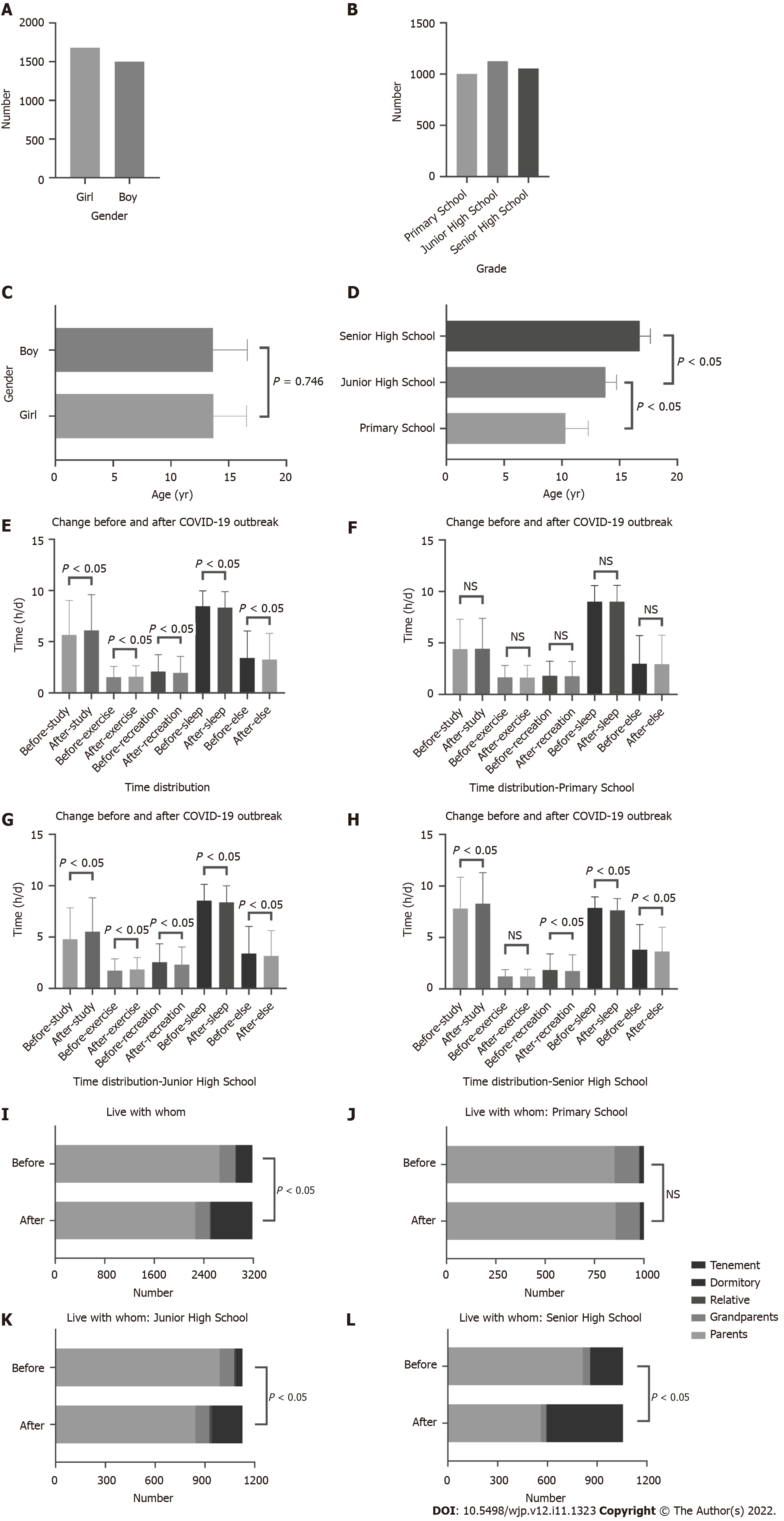

We collected 3273 questionnaires, of which 3184 were included in the analysis, with an effective rate of 97.28%. The sample included 1682 (52.8%) female respondents (Figure 1A). The sample included students in primary school (n = 1002, 31.47%), junior high school (n = 1126, 35.36%), and senior high school (n = 1056, 33.17%) (Figure 1B). Participants’ ages ranged from 6 to 19 years (mean: 13.67; SD: 2.92) (Figure 1C). Primary school students’ ages ranged from 6–15 years of age (mean: 10.31; SD: 1.97), junior high school students’ ages ranged from 9–18 years (mean: 13.79; SD: 0.95), and senior high school students’ ages ranged from 13–19 years (mean: 16.74; SD: 0.93). There were significant differences in age distribution among the three cohorts (Figure 1D).

The time distribution of the study, exercise, recreation, sleep, and else exhibited a significant difference between before and after COVID-19 (Figure 1E). We further analyzed the different grades’ subgroups and found no difference among primary school students (Figure 1F). Among junior high school students, more time was spent studying and exercising after the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before, whereas less time was spent on recreation, sleep, and else (Figure 1G). The same tendency was observed among senior high school students, except for exercise (Figure 1H).

There has a significant difference in living with whom between before and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1I). Further analysis demonstrated no differences among primary school students (Figure 1J), but there are significant differences between junior high school and senior high school students (Figure 1K and L). The main change was that fewer students lived with their parents, and most lived on campus.

Despite all of the inconveniences caused by COVID-19, the results revealed some positive impacts of the pandemic for adolescents (Table 1). Scores of −1 denoted “strongly disagree”, −0.5 denoted “slightly disagree”, 0 denoted “neutral”, 0.5 denoted “slightly agree”, and 1 denoted “strongly agree”. We calculated approval scores for each item, and the proportion of people giving each response. The survey showed that participants in all grades unanimously approved of the following items: Increased time staying at home, increased time spent with parents, and increased time spent on personal matters. Conversely, the following items were unanimously disagreed with by participants in all grades: Do not have to go to school, and decreased monitoring by teachers.

| Mean point [-1,1] | Disagree | Agree | |

| Do not have to go to school | |||

| All | -0.307 | 50.5% | 15% |

| Primary school | -0.370 | 55.4% | 12.8% |

| Junior high school | -0.256 | 47.5% | 19% |

| Senior high school | -0.303 | 49.1% | 13.0% |

| Increased time staying at home | |||

| All | 0.082 | 23.4% | 37.9% |

| Primary school | 0.021 | 27.2% | 34.4% |

| Junior high school | 0.149 | 21.7% | 43.2% |

| Senior high school | 0.070 | 21.7% | 35.6% |

| Increased time spent with parents | |||

| All | 0.232 | 15.5% | 49.6% |

| Primary school | 0.157 | 18.0% | 43.8% |

| Junior high school | 0.342 | 13.1% | 58.0% |

| Senior high school | 0.185 | 15.9% | 46.0% |

| Increased time spent in personal stuff | |||

| All | 0.159 | 18.7% | 42.9% |

| Primary school | 0.059 | 23.2% | 35.4% |

| Junior high school | 0.246 | 16.3% | 48.6% |

| Senior high school | 0.161 | 17.1% | 43.8% |

| Decreased teachers’ monitoring | |||

| All | -0.182 | 42% | 20.6% |

| Primary school | -0.248 | 47.6% | 18.4% |

| Junior high school | -0.163 | 41.4% | 22.3% |

| Senior high school | -0.140 | 37.2% | 20.9% |

Ratings of −1 denoted “strongly disagree”, −0.5 denoted “slightly disagree”, 0 denoted “neutral”, 0.5 denoted “slightly agree”, and 1 denoted “strongly agree”. We calculated statistical approval scores for each item, and the proportion of people giving each response.

We examined the main academic-related concerns of adolescents (Table 2). The investigation demonstrated that the following items were unanimously approved of by participants in all grades: Worry about the future, and interference with academic performance. Conversely, all grade members unanimously disagreed with the following items: Difficulty concentrating, unable to adapt to online classes, and feeling an increase in homework. Regarding increased parents’ monitoring, with age, adolescents gradually shifted from agreeing to disagreeing with this item.

| Learning effects | Mean point | Disagree | Agree | Life influence | Mean point | Disagree | Agree |

| Increased parents’ monitoring | Distance from friends | ||||||

| All | 0.073 | 20.1% | 33.2% | All | -0.111 | 34.0% | 23.0% |

| Primary school | 0.165 | 17.5% | 44.4% | Primary school | 0.017 | 25.2% | 32.2% |

| Junior high school | 0.090 | 19.9% | 34.0% | Junior high school | -0.204 | 42.6% | 20.3% |

| Senior high school | -0.031 | 22.7% | 21.6% | Senior high school | -0.134 | 33.0% | 17.1% |

| Difficulty concentrating | Don't socialize with people | ||||||

| All | -0.098 | 34.3% | 24.6% | All | -0.243 | 44.5% | 14.6% |

| Primary school | -0.051 | 31.1% | 27.6% | Primary school | -0.160 | 38% | 18.3% |

| Junior high school | -0.185 | 42.2% | 21.0% | Junior high school | -0.353 | 54.3% | 12.7% |

| Senior high school | -0.051 | 28.9% | 25.6% | Senior high school | -0.205 | 40.2% | 13.1% |

| Worry about the future | Less entertainment | ||||||

| All | 0.065 | 25.3% | 37.1% | All | -0.02 | 27.1% | 26.7% |

| Primary school | 0.031 | 27.9% | 34.4% | Primary school | 0.076 | 21.1% | 34.1% |

| Junior high school | 0.101 | 25.8% | 42.0% | Junior high school | -0.119 | 36.4% | 21.9% |

| Senior high school | 0.058 | 22.2% | 34.5% | Senior high school | -0.005 | 22.9% | 24.7% |

| Interference with academic performance | Reduce pocket money | ||||||

| All | 0.108 | 23.4% | 40.6% | All | -0.209 | 37.4% | 11.1% |

| Primary school | 0.072 | 26.1% | 37.9% | Primary school | -0.192 | 34.9% | 10.8% |

| Junior high school | 0.160 | 23.3% | 46.2% | Junior high school | -0.243 | 43.9% | 13.9% |

| Senior high school | 0.086 | 21.0% | 37.1% | Senior high school | -0.187 | 33.0% | 8.2% |

| Unable to adapt to online classes | Pay more attention to news reports | ||||||

| All | -0.057 | 31.3% | 25.7% | All | 0.236 | 11.9% | 48.2% |

| Primary school | -0.027 | 30.5% | 28.8% | Primary school | 0.193 | 12.0% | 45.0% |

| Junior high school | -0.092 | 35.6% | 25.5% | Junior high school | 0.236 | 14.7% | 46.8% |

| Senior high school | -0.050 | 27.6% | 22.9% | Senior high school | 0.278 | 8.8% | 52.7% |

| Feel an increase in homework | Change of living environment | ||||||

| All | -0.167 | 35.3% | 14.4% | All | 0.091 | 18.5% | 35.1% |

| Primary school | -0.242 | 41.5% | 10.8% | Primary school | 0.119 | 15.9% | 37.6% |

| Junior high school | -0.160 | 38.5% | 18.8% | Junior high school | 0.067 | 23.4% | 34.3% |

| Senior high school | -0.105 | 26.0% | 13.3% | Senior high school | 0.090 | 15.7% | 33.6% |

| Less travel | |||||||

| All | 0.317 | 13.4% | 53.7% | ||||

| Primary school | 0.407 | 11.7% | 60.9% | ||||

| Junior high school | 0.258 | 17.4% | 49.5% | ||||

| Senior high school | 0.295 | 10.8% | 51.4% | ||||

| Feel the traffic is inconvenient | |||||||

| All | 0.072 | 20.8% | 32.2% | ||||

| Primary school | 0.108 | 10.7% | 35.3% | ||||

| Junior high school | 0.030 | 26.6% | 30.6% | ||||

| Senior high school | 0.083 | 15.5% | 31.1% | ||||

| Hospital care is harder | |||||||

| All | 0.145 | 18.5% | 39.7% | ||||

| Primary school | 0.205 | 17.1% | 44.5% | ||||

| Junior high school | 0.095 | 23.4% | 37.7% | ||||

| Senior high school | 0.142 | 14.6% | 37.4% |

Various lifestyle-related concerns are presented in Table 2. The results revealed that the following items were unanimously approved of by participants in all grades: Pay more attention to news reports, change in living environment, less travel, increased inconvenience of traffic, more difficulty in accessing hospital care. Conversely, the following items were unanimously disapproved of by participants in all grades: Do not socialize with people, reduce pocket money. Participants in different grades expressed different views on the following items: Distance from friends and less entertainment.

The PHQ-9 survey results are shown in Table 3. 34.6% of adolescents were depressed before the COVID-19 pandemic, of which 1.9% were severely depressed. The proportion of adolescents with depression was highest among senior high school students, at 39.8%. The proportion of adolescents with severe depression was highest among junior school students, at 3.5%. After the COVID-19 pandemic, 26.3% of adolescents exhibited depression, of which 1.4% were severely depressed. The highest proportion of adolescents with severe depression was observed among junior high school students, at 2.8%. The highest proportion of depressed students was observed among senior high school students, at 28.9%. Overall, depression improved among adolescents after the COVID-19 pandemic.

| n | Mean (95%CI) | Level of severity, n (%) | |||||

| Minimal (0-4) | Mild (5-9) | Moderate (10-14) | Moderately severe (15-19) | Severe (≥ 20) | |||

| Before COVID-19 | |||||||

| Whole sample | 3184 | 3.862 (3.685-4.043) | 2083 (65.4) | 779 (24.5) | 183 (5.7) | 78 (2.4) | 61 (1.9) |

| Primary school | 1002 | 3.329 (3.036-3.623) | 702 (70.1) | 227 (22.7) | 37 (3.7) | 24 (2.4) | 12 (1.2) |

| Junior high school | 1126 | 4.211 (3.863-4.560) | 746 (66.3) | 224 (19.9) | 83 (7.4) | 34 (3.0) | 39 (3.5) |

| Senior high school | 1056 | 4.001 (3.726-4.276) | 635 (60.1) | 328 (31.1) | 63 (6.0) | 20 (1.9) | 10 (0.9) |

| Post COVID-19 | |||||||

| Whole sample | 3184 | 2.932 (2.763-3.102) | 2348 (73.7) | 607 (19.1) | 116 (3.6) | 67 (2.1) | 46 (1.4) |

| Primary school | 1002 | 2.277 (2.016-2.539) | 787 (78.5) | 175 (17.5) | 17 (1.7) | 16 (1.6) | 7 (0.7) |

| Junior high school | 1126 | 3.383 (3.046-3.719) | 810 (71.9) | 196 (17.4) | 54 (4.8) | 35 (3.1) | 31 (2.8) |

| Senior high school | 1056 | 3.074 (2.810-3.338) | 751 (71.1) | 236 (22.3) | 45 (4.3) | 16 (1.5) | 8 (0.8) |

The GAD-7 scale results are shown in Table 4, 24.4% of adolescents had anxiety before the COVID-19 pandemic, with severe anxiety accounting for 1.6%. The highest rate of anxiety was among senior high school students, at 29.4%. The proportion of adolescents with severe anxiety was highest among junior high school students, at 2.8%. After the COVID-19 pandemic, 23.5% of adolescents were prone to anxiety, of which 1.7% were severely anxious. Senior high school students had the highest rate of anxiety, at 27.4%. The highest rate of severe anxiety was observed among junior high school students, at 3.6%. Thus, the results revealed that after the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of anxiety was alleviated among senior high school students, whereas junior high school students were more severely affected. This issue deserves the attention of the education department.

| n | Mean (95%CI) | Level of severity, n (%) | ||||

| Minimal (0-4) | Mild (5-9) | Moderate (10-14) | Severe (15-21) | |||

| Before COVID-19 | ||||||

| Whole sample | 3184 | 2.465 (2.330-2.600) | 2408 (75.6) | 627 (19.7) | 98 (3.1) | 51 (1.6) |

| Primary school | 1002 | 1.984 (1.766-2.202) | 802 (80.0) | 168 (16.8) | 22 (2.2) | 10 (1.0) |

| Junior high school | 1126 | 2.598 (2.340-2.856) | 860 (76.4) | 186 (16.5) | 49 (4.4) | 31 (2.8) |

| Senior high school | 1056 | 2.780 (2.563-2.997) | 746 (70.6) | 273 (25.9) | 27 (2.6) | 10 (0.9) |

| Post COVID-19 | ||||||

| Whole sample | 3184 | 2.273 (2.133-2.412) | 2436 (76.5) | 584 (18.3) | 109 (3.4) | 55 (1.7) |

| Primary school | 1002 | 1.775 (1.557-1.994) | 813 (81.1) | 156 (15.6) | 23 (2.3) | 10 (1.0) |

| Junior high school | 1126 | 2.536 (2.262-2.809) | 856 (76.0) | 182 (16.2) | 48 (4.3) | 40 (3.6) |

| Senior high school | 1056 | 2.464 (2.246-2.682) | 767 (72.6) | 246 (23.3) | 38 (3.6) | 5 (0.5) |

We collected mental health questionnaires from 3184 students. Participants’ gender and grade were relatively evenly distributed in the sample. The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant changes in the schedules of junior high school and senior high school students, but had little impact on primary school students, possibly because junior high school and senior high school students are more likely to live in school accommodation. With age, adolescents allocate more time to study and less time to play and sleep. This bias may have been partially caused by the study period of approximately 2 years. Some students begin living in the school dormitory after entering a higher grade. To reduce the flow of students, some schools adopted a closed management mode.

In a survey of positive factors, participants most strongly agreed that they had spent more time with their parents since the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, participants disagreed most strongly that they did not have to go to school after the pandemic. Closing schools was not common practice in Chinese schools when the pandemic was not severe. A survey of negative effects revealed that adolescents most strongly agreed that the impact of COVID-19 on academic performance was relatively severe. Students’ learning styles and efficiency may have changed significantly after the pandemic outbreak, and most students faced difficulty adapting. The most negatively rated factor was the increase in homework. The results suggested that the amount of homework for students after the outbreak was less than before. In terms of the impact on their lives, students most strongly agreed that they traveled less. After the outbreak of COVID-19, to avoid gathering together, most participants reduced the number of trips they took. As a non-essential entertainment activity, most participants reported having given up traveling. Students disagreed most strongly with the lack of communication with people, especially junior high school students. With the development of science and technology, although offline communication has decreased, online communication through WeChat and QQ may have become more frequent and intimate.

We note that some psychologists use the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) scale to assess adolescents’ mental health[10]. However, only a few studies have validated the PHQ-A under research conditions[11,12]. In contrast, the PHQ-9 has been extensively validated worldwide and has been confirmed as a practical and rigorous scale for all populations, including adolescents[13-16]. After careful consideration, our team adopted the PHQ-9 scale so that more researchers would be able to interpret the results. The PHQ-9 scale results suggested that the prevalence of depression among adolescents improved after the outbreak of COVID-19 compared with before the pandemic. One possible reason for this finding is that students’ academic burden was reduced, and the measures taken to reduce the students’ campus contact may have indirectly reduced bullying.

The GAD-7 scale results indicated a similar decrease in panic and anxiety among adolescents after COVID-19. Senior high school students exhibited a significant improvement in GAD symptoms. This finding may have been caused by the greater resilience of high school students as they get older, and the larger number of people living in the dormitory with less parental supervision. Anxiety symptoms among junior high school students were not alleviated after the COVID-19 pandemic, and a higher proportion of junior high school students reported worrying about the future and felt that their academic performance declined after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The current study provided new data regarding the mental health of Chinese adolescents. Several previous studies have examined adolescent mental health in other countries. A study in the United Kingdom of 886 adolescents revealed different effects on adolescents’ mental health, depending on their mental health and socio-demographic background prior to the pandemic[17]. A survey conducted in the United States with 682 university students suggested that physical disruption was a significant risk factor for depression during the pandemic. However, short-term interventions to restore these habits were reported to be ineffective for improving mental health[18]. A sample of 1337 adolescents in the United Kingdom revealed a significant association between loneliness and concurrent mental health difficulties among adolescents in the United Kingdom at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Teens that were closer to their parents had lower levels of emotional distress, and adolescents who spent more time texting others tended to have more symptoms of mental health difficulties[19]. A survey of 2224 people in the United States revealed that income loss during the pandemic adversely affected the worsening of depressive symptoms among adolescents[20]. COVID-19 home quarantine rules were suggested to have protective effects on adolescents’ mental health in a survey of 322 predominantly Hispanic/Latinx youth in the United States[21]. A Dutch survey of 239 patients with rheumatoid arthritis reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had little psychological impact on patients with underlying conditions, possibly because general education and health care were available for most patients[22].

Some previous studies of adolescent mental health have been conducted in China. A study of 1241 primary and junior high school students in Anhui, China, reported that mental health was associated with the length of school closures caused by COVID-19, and that enforced social isolation by disease control measures was associated with future mental health problems among children and adolescents[23]. A survey of 687 people in Wuhan, China, revealed that by the end of the lockdown, levels of depression and anxiety had risen among a significant number of Chinese people, with students and other medical staff being most affected, while economic workers also experienced stress[24]. The mental health of more than one in five middle and high school students in China was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a survey of a sample of 1025 middle and high school students in Guangzhou, China. The results indicated that resilience and actively responding can improve students’ psychological and mental health. In contrast, negative coping is a risk factor for mental health[25]. A sample survey of 4342 primary and secondary school students from Shanghai, China, reported the coexistence of mental health problems and resilience among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parent–child discussions can play an important role in addressing this issue, and parents and children should be encouraged to communicate openly about the pandemic[1]. An extensive survey of 11681 Chinese adolescents reported that non-only children were more likely than only children to experience symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly those with fewer parent–child connections, low resilience, and experiences of emotional abuse[26]. However, the studies mentioned above did not completely cover the three grades of primary school, middle, and high school, and conducted systematic analysis of a large sample population of different grades.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. We contacted schools in Beijing, Guangdong, and Heilongjiang provinces and distributed questionnaires online, hoping to collect representative samples in the central, southern, and northern regions. However, our sample is still not representative of all Chinese adolescents. In addition, the questionnaire collected double cross-sectional data before and after the pandemic in a single release, which may be biased compared with a prospective design for collecting data at two time-points. Unfortunately, we were not able to predict the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study had the following advantages. First, the sample size was relatively large compared with other published studies of adolescents. Additionally, we described the characteristics of the sample in detail and demonstrated the positive factors and negative impacts for adolescents in terms of life and learning before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, to avoid subjective bias, we also used the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales for objective and quantitative assessment, increasing the reliability of the results. Moreover, we also carried out a statistical analysis of the adolescents divided into three groups according to grade. The characteristics of adolescents in different grades were discussed in detail to provide a theoretical basis for optimizing educational measures in different grades. Furthermore, the current study is the most comprehensive and detailed study of adolescent psychological health characteristics in different grades to date.

The current results revealed a reduction in depression and anxiety among adolescents after the COVID-19 pandemic, except anxiety symptoms in junior high school students. Although this conclusion differs from the findings of most previous studies of this issue, it is supported by a small number of studies suggesting the need for a greater focus on students’ mental health, rather than academic performance alone, when the COVID-19 pandemic is over and the public returns to ordinary life[21]. The partial educational management practices that have changed since the COVID-19 pandemic may be worth learning from and optimizing in long-term educational planning.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has severely affected adolescents' mental health.

Based on the results, adolescent mental health interventions would be developed or adjusted.

The study investigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Chinese adolescents.

A multicenter cross-sectional comparative survey of Chinese adolescents was conducted in March 2022 to collect demographic information, survey data, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener scale scores related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The investigation demonstrated that adolescents most strongly agreed with the following items: Increased time spent with parents, interference with academic performance, and less travel. Conversely, adolescents most strongly disagreed with the following items: Not having to go to school, feeling an increase in homework, and not socializing with people; 34.6% of adolescents were depressed before COVID-19, after COVID-19, 26.3% of adolescents were prone to depression. 24.4% of adolescents had anxiety before COVID-19, and after COVID-19, 23.5% of adolescents were prone to anxiety.

After the COVID-19 outbreak, the anxiety and depression levels of Chinese adolescents in different grades have improved.

Changes in educational management practices since the COVID-19 pandemic may be worth learning from and optimizing long-term educational planning.

| 1. | Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, Huang E, Zuo QK. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1486:90-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 95.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marelli S, Castelnuovo A, Somma A, Castronovo V, Mombelli S, Bottoni D, Leitner C, Fossati A, Ferini-Strambi L. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on sleep quality in university students and administration staff. J Neurol. 2021;268:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 73.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating Mental Health of US College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e22817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 693] [Article Influence: 115.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 5. | Kwong ASF, Pearson RM, Adams MJ, Northstone K, Tilling K, Smith D, Fawns-Ritchie C, Bould H, Warne N, Zammit S, Gunnell DJ, Moran PA, Micali N, Reichenberg A, Hickman M, Rai D, Haworth S, Campbell A, Altschul D, Flaig R, McIntosh AM, Lawlor DA, Porteous D, Timpson NJ. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;218:334-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fu W, Yan S, Zong Q, Anderson-Luxford D, Song X, Lv Z, Lv C. Mental health of college students during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. J Affect Disord. 2021;280:7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1087] [Cited by in RCA: 971] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 31491] [Article Influence: 1259.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46:266-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1978] [Cited by in RCA: 3077] [Article Influence: 170.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | O'Dea B, Han J, Batterham PJ, Achilles MR, Calear AL, Werner-Seidler A, Parker B, Shand F, Christensen H. A randomised controlled trial of a relationship-focussed mobile phone application for improving adolescents' mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:899-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Watson SE, Spurling SE, Fieldhouse AM, Montgomery VL, Wintergerst KA. Depression and Anxiety Screening in Adolescents With Diabetes. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Anand P, Bhurji N, Williams N, Desai N. Comparison of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 as Screening Tools for Depression and School Related Stress in Inner City Adolescents. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211053750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, Guo ZC, Wang JQ, Chen JC, Liu M, Chen X, Chen JX. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29:749-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 677] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 141.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sinclair-McBride K, Morelli N, Gusman M. PHQ-9 Administration in Outpatient Adolescent Psychiatry Services. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:837-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leung DYP, Mak YW, Leung SF, Chiang VCL, Loke AY. Measurement invariances of the PHQ-9 across gender and age groups in Chinese adolescents. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020;12:e12381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hu Y, Qian Y. COVID-19 and Adolescent Mental Health in the United Kingdom. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Giuntella O, Hyde K, Saccardo S, Sadoff S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cooper K, Hards E, Moltrecht B, Reynolds S, Shum A, McElroy E, Loades M. Loneliness, social relationships, and mental health in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021;289:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pinchoff J, Friesen EL, Kangwana B, Mbushi F, Muluve E, Ngo TD, Austrian K. How Has COVID-19-Related Income Loss and Household Stress Affected Adolescent Mental Health in Kenya? J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:713-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Penner F, Hernandez Ortiz J, Sharp C. Change in Youth Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Majority Hispanic/Latinx US Sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60:513-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Koppert TY, Jacobs JWG, Geenen R. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Dutch people with and without an inflammatory rheumatic disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:3709-3715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang L, Zhang D, Fang J, Wan Y, Tao F, Sun Y. Assessment of Mental Health of Chinese Primary School Students Before and After School Closing and Opening During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2021482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Du J, Mayer G, Hummel S, Oetjen N, Gronewold N, Zafar A, Schultz JH. Mental Health Burden in Different Professions During the Final Stage of the COVID-19 Lockdown in China: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e24240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang C, Ye M, Fu Y, Yang M, Luo F, Yuan J, Tao Q. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teenagers in China. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:747-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cao Y, Huang L, Si T, Wang NQ, Qu M, Zhang XY. The role of only-child status in the psychological impact of COVID-19 on mental health of Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:316-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hirooka Y, Japan; Hirst L, United Kingdom; Lyman GH, United States S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu XF