INTRODUCTION

The aim of the present review is to throw light on the similarities between binge eating disorder and substance use disorders by exploring the most recent research about how bingeing on palatable food can influence vulnerability to the development of psychostimulant addiction. We address how the two disorders co-occur, and discuss the need for new forms of treatment and therapies that approach the problem as a dual pathology.

In all species of the animal kingdom, nutrition is crucial for the maintenance of adequate energy stores for survival. Mammals need to maintain a stable body temperature, and as they have a high metabolic rate, they require a constant supply of large amounts of energy[1]. That is the reason why mammalian brains have evolved to develop several neuronal systems that drive feeding behavior, with the rewarding nature of eating being one of the most potent drives behind feeding[2]. Beyond the homeostatic regulation of food intake, and in order to promote survival, the complex neural networks within the brain drive individuals to seek the most caloric foods. During evolution, our organism has developed in a context of nutritional shortage, so we have an innate biological preference for that type of food. That is why palatable foods high in fat, sugar, and salt induce a potent release of dopamine in our brain reward system, producing a great feeling of pleasure[3].

As a consequence of the brain’s bias towards palatable food, overeating and obesity are global diseases of our modern society, even though both are preventable. For many years, malnutrition was a common problem, but now, according to the most recent report of the World Health Organization[4], worldwide obesity rates have more than tripled since 1975, and it now kills more people than undernourishment. In 2016, 39% of the world population over 18 years of age was overweight and 13% were obese. This problem is especially critical in children and young people, who are more vulnerable to inadequate dietary habits and are overexposed to high-fat, high-sugar, high-salt, energy-dense foods of lower nutritional quality. In 2016, 41 million children under 5 years of age worldwide were overweight or obese. The progressive and continuous increase in metabolic diseases and overweight is related to obesogenic environmental factors, such as the high number of fast food establishments, the decrease in physical activity associated with the sedentary nature of many forms of work, transportation choices, and increased urbanization[4,5]. The rise in obesity rates worldwide has encouraged extensive research to improve our understanding of the problem, particularly the excessive intake of food, and especially that of sugary and fatty foods, which has become a serious health problem for our society.

The 21st century society is characterized by the consumption of ultraprocessed food that is high in fat and sugar and is often eaten for pleasure rather than survival; in this context, Gold[6] defined "hedonic eating" as eating based on pleasure rather than energy needs. Research to date shows that hedonic eating modulates neural mechanisms related to reward processing[7], the same circuits activated by drugs of abuse, which explains the maintenance and escalation of this behavior. The brain reward system is designed to play a crucial role in basic survival activities, such as eating, sex or sleep[1]. However, we are currently facing a situation in which palatable food not only supports our survival but also modulates our brain function and behavior.

Drugs of abuse target the abovementioned reward system, inducing an overstimulation of the circuitry that eventually overrides the pleasurable effects of other basic activities[8]. As with other psychiatric disorders, not all humans have the same risk of developing an addiction, and the risk varies considerably from one person to another. There are many different factors, characteristics, and variables involved in the addictive process, and they determine an individual’s vulnerability to develop this disease. In general, the more risk factors found in a person, the greater is the probability of developing a substance use disorder after taking drugs occasionally[9]. Among the environmental and lifestyle variables under investigation in recent years are nutritional habits and eating patterns, which not only contribute to the obesity epidemic, but also affect our mental health and can lead to the development of a substance use disorder[10].

The latest research suggests that both drug addiction and obesity are disorders in which the value of drug or food reinforcement, respectively is abnormally increased in relation to and at the expense of other reinforcements[7,10]. Both drugs and food have powerful rewarding effects mediated by increases in dopamine release in the limbic system that, under certain circumstances or in vulnerable subjects, can alter the homeostatic control mechanisms of hunger and satiety[7,11,12]. For example, it has been shown that individuals with a substance use disorder or obesity have a reduced number of dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens[7], and the neuroadaptation has been directly related to a decrease in the basal activity of the frontal regions involved in reward and inhibitory control[13].

Adolescent populations today are often characterized by abnormal dietary habits and lower levels of physical activity, resulting in an increased percentage of overweight adolescents that will later become obese adults. Apart from the risk of developing obesity-derived cardiovascular diseases such as diabetes, it is important to bear in mind that adolescents are more prone than adults to develop eating disorders, such as anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating[14]. Moreover, nonclinical binge eating behavior is very common among the adolescent population, as every weekend a high percentage of this age group engages in episodes of excessive intake of fast food combined with the consumption of large amounts of alcohol and other substances of abuse. The adolescent brain works in a promotivational state, with a strong, fully developed reward system, but still developing inhibitory control areas, such as the prefrontal cortex[15]. Although basal levels of synaptic dopamine are lower during adolescence, there is an increase in drug-induced dopamine release during this period[16,17]. As a consequence, teenagers exposed too early to these potent rewards may suffer from an unbalanced brain reward system when they become adults[18,19].

As several studies have reported that drug use early on in life often predicts an increased likelihood of continued use into adulthood[20], a gateway theory has also been applied to eating disorders[21]. According to the theory, binge eating can lead to the development of another maladaptive behavior, such as drug abuse. The literature available to date points to the mutual influence of palatable diets and psychostimulants, but there is a need to increase awareness of the problem and to perform more studies in humans to confirm the data obtained in preclinical studies.

COMMONALITIES BETWEEN BINGE EATING DISORDER AND DRUG ADDICTION

Behavioral commonalities between binge eating disorder and substance use disorder

The interaction between drug abuse and food, hunger, and appetite, has not inspired interest only in recent times. Since the earliest recorded use of cocaine, indigenous peoples have consumed the drug in order to boost energy levels that allow them to work at high altitude and also to reduce appetite[22]. When cocaine consumption spread to other cultures, cocaine abusers in the United States would report forgetting to eat on many occasions, and had multiple nutritional deficiencies, anorexia and weight loss. Similar observations have been made with respect to methamphetamine, amphetamine, and ecstasy consumers. Under these circumstances, psychostimulants and food compete, and drugs would seem to be the winner[6]. Moreover, although psychostimulants like cocaine or amphetamine produce few withdrawal symptoms, they lead to multiple alterations in appetite and mood[23].

Among eating disorders, binge eating is highly prevalent. The DSM-5 defines binge eating as recurring episodes of rapid and excessive food consumption in a short period of time, marked by feelings of lack of control, and not necessarily driven by hunger or metabolic need[24]. Although binge eating is related to obesity, many people who binge are not obese, and most obese people do not present binge eating disorder[25]. Binge eating and substance use disorders belong to the family of intermittent excessive behaviors, which are associated with loss of control and are clinically comorbid[26,27]. Forms of psychostimulant consumption vary considerably among individuals, with the appearance of a binge pattern being very frequent. Binges or "runs" are defined as the way cocaine is consumed in an intense and repetitive manner over several hours and days[28]. This pattern of cocaine intake is associated with increased medical and psychiatric consequences and is linked to worse health and social outcomes[29,30].

To date, research has revealed a high comorbidity between binge eating and substance use disorders[31], which complicates the evaluation and treatment of both disorders[32] and increases low adherence to treatment[33,34]. An early study at the Center for Addiction and Substance Abuse of the University of Columbia[35] reported that the prevalence of drug abuse was 50% in the case of individuals suffering from eating disorders, while it was around 9% in the general population. On the other hand, 35% of people diagnosed with a substance use disorder exhibited comorbidity with eating disorders, compared with 1%-3% of the general population. More recently, a study performed by an Addictive Behavior Treatment Unit in Spain demonstrated a higher prevalence of eating disorders in a population with substance use disorder[36]. Participants who presented with a substance use disorder had higher scores on all scales indicating the presence of an eating disorder, with values proving especially high in women. A recent study in a university sample showed that binge eating and fat intake were positively related to binge drinking in students[37].

Current research is focused on the symptomatic and neurobiological similarity between alterations in appetite and satiety, obsessive and impulsive disorders, self-destructive behaviors and medical consequences[38]. Among the shared characteristics, several drug addiction symptoms were also observed in individuals with a binge eating disorder[39,40]. Consuming drugs or eating palatable food are both motivated appetitive behaviors with common aspects, and both can evolve into addictive behavior[41]. Both eating disorders and drug abuse commonly begin during a vulnerable period, such as adolescence. In the same way as an individual with a drug addiction ignores responsibilities or obligations in order to take drugs, people with a binge eating disorder devote all their energy to bingeing, purging, exercising, and making efforts to lose weight[42]. Similar to drug abuse, individuals engage in eating disorders despite the serious consequences of the acts in question, making them vulnerable to relapse after periods of regular behavior[43].

Common neurobiology: The dopaminergic, opioid and cannabinoid systems

The brain reward system is clearly the most important neurotransmitter system involved in binge eating and substance use disorders, which are characterized by the impulsive and compulsive intake of drugs or highly palatable food[44,45]. Although multiple neurotransmitters are implicated, the dopamine and opioid systems are the main regulators of feeding behaviors and drug addiction[44,46]. While dopamine is involved in the motivation toward a rewarding activity and its subsequent conditioning, opioids participate in the enjoyment and pleasurable effects of the rewarding activity[47,48]. However, the two pathways do not function independently, and both can be altered by other neurotransmitters[47]. For example, dopaminergic signals can be modified by endogenous opioids, while opioid signaling needs a dopamine D2 receptor to work correctly. In line with this, Smith and Robbins[49] reported that both substance use disorders and binge eating disorder are related by dysfunctional dopaminergic and opioid signaling as well as decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex area, a brain area associated with inhibitory control and decision making. Other studies have found common polymorphisms in the mu-opioid receptor gene and the D2 receptor gene in a sample of individuals with binge eating and substance use disorders, and it has been proposed that the polymorphisms increase vulnerability to the rewarding effects of food and drugs[47,50].

The predisposition to emotion-based impulsive actions observed in both binge eating disorder and substance use disorders[51] can also be explained by neurobiology. Every time an individual takes a drug there is a massive dopamine release that results in a pronounced subjective perception of reward[52]. This experience leads the individual to choose this option to regulate their positive or negative emotional state. Over time, drug use induces changes in neuroplasticity that increase the brain’s reward threshold, so that the user requires more drug more frequently to achieve the same pleasurable effects[53]. At this stage, the brain produces neuroadaptations; the effectiveness of dopamine D2 receptors decreases, which is accompanied by a reduced sensitivity to the rewarding effects of other natural reinforcers[54]. These decreased striatal dopamine D2 receptor levels are present in humans with substance use disorder and in animal models of compulsive drug intake[55].

Regarding binge eating disorder, research shows that women with bulimia nervosa tend to have lower levels of dopamine receptors, and a negative correlation has been highlighted between episodes of binge eating, purging, and striatal dopamine response[56]. Similar to that seen with drugs of abuse, increasingly higher amounts of dopamine need to be released to obtain the same pleasurable effect of palatable food[57]. A decrease in dopamine D2 receptors in the striatum and nucleus accumbens has been described in rats bingeing on sugar[58]. Similarly, after 30 d of intermittent access to a high-sugar beverage, a decrease in dopamine D2 receptors and an increase in dopamine D1 receptors in the dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens have been described in the same species[59]. Alterations in D2 regulation are related with compulsive drug abuse and binge eating in rodents, with a shift from reward-directed consumption to a compulsive drug and food intake[60,61]. On the other hand, studies in humans have reported alterations in dopamine turnover and receptors in individuals with binge eating disorder[7,62].

Endogenous opioids play an important role in the positive experience associated with eating, both in humans and in animals[63]. Activation of the mu-opioid receptor increases dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens by inhibiting GABAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area[64,65]. Normally, these neurons provide a tonic-like inhibition of dopamine neurons, but inhibiting this process results in an increase in dopamine release[66]. Studies to date have shown how nutritional conditions can significantly dysregulate the function of the endogenous opioid system, contributing to a worsening of different eating disorders, including binge eating disorder. In fact, some eating disorders have been shown to modify plasma beta-endorphin levels and induce alterations in mu-receptor function[67,68]. We have recently reported decreased gene expression of the mu-opioid receptor in the nucleus accumbens of animals that binged on fat[69]. As an example of the important role that opioids play in binge eating, medications like naltrexone, an opioid antagonist used to treat substance use disorders, work by reducing the frequency of binge eating and purging in bulimia nervosa, and through the positive perception of highly palatable foods[70].

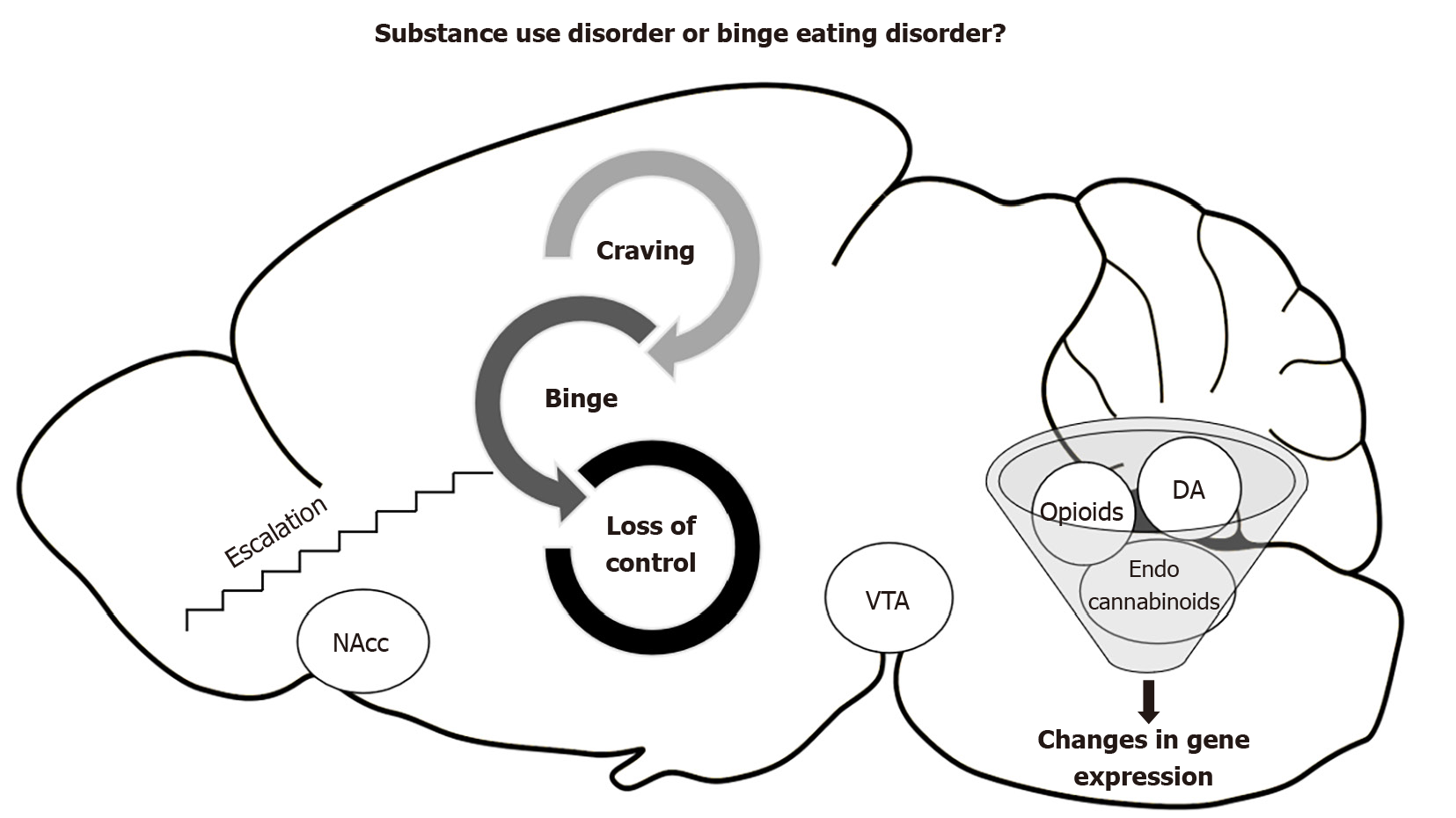

Lastly, a promising therapeutic target is the endocannabinoid system, which is a key point of the regulatory network that controls energy homeostasis[71]. While the opioid is dopamine-anticipating food, the endocannabinoid system is related to the homeostatic control of intake and positive feedback of the specific intake of fatty food[72]. Hypothalamic endocannabinoids control food intake by decreasing satiety signals and increasing orexigenic signals[73]. Moreover, they modulate reward mechanisms by interacting with the mesolimbic pathways, increasing the motivation to eat and possibly reinforcing the incentive or hedonic value of food[74]. Some studies have discovered alterations in anandamide, an endogenous cannabinoid ligand, in patients with anorexia and binge eating disorder, but not in those with bulimia nervosa, suggesting a possible involvement of endocannabinoids in the rewarding aspects of aberrant eating behaviors[75]. Recent animal studies have highlighted changes in brain levels of anandamide in rats that binge on fat[76] and changes in CB1r gene expression in the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens[69]. The neurobiological relationship between substance use disorders and binge eating disorder is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Relationship between substance use disorders and binge eating disorder.

DA: Dopamine; NAcc: Nucleus accumbens; VTA: Vental tegmental area.

ANIMAL STUDIES: PALATABLE FOOD SENSITIZES TO DRUG ADDICTION

In this section we will review a series of basic studies focused on intermittent and limited access to palatable food, which mimics binge eating disorder and induces an escalation in intake over time. Currently, there is evidence that the composition of a diet, such as the percentage of sugar or fat, can affect the intake of drugs of abuse. Laboratory animal models are useful for understanding the factors that contribute to both disorders, helping to broaden horizons and open new perspectives of treatment[42]. As we have previously explained, psychological and biological similarities between palatable food intake and addiction to drugs of abuse have previously been reported, highlighting common reward mechanisms and suggesting that nutritional status is an important factor in the development of addiction[7].

Some authors have implied that, rather than the food itself, it is the way food is consumed that alters the reward system and contributes to vulnerability to other addictive disorders[77,78]. Current research mainly concentrates on two animal eating patterns that modulate reward system function, continuous access vs limited access models. While continuous ad libitum access to palatable diets creates animal models of obesity and metabolic syndrome, the limited access model resembles binge eating in its intermittent pattern[78]. Although animal models of binge eating reveal behaviors similar to those seen in humans, they mimic only some of the characteristics of the human disorder. They do not include blame, guilt, the sense of losing control, or the social influence of human eating behavior[79]. Despite these limitations, they share numerous features with human patterns of eating; for example, animals ingest a large amount of food in a brief period of time, exceeding the quantity that an animal maintained on a standard diet would eat in similar circumstances[80].

There are three binge eating models that have been the most widely used to date. The model of sugar bingeing proposed by Avena[58] was the first animal model of food addiction. In that model, animals have intermittent access to a 10% sugar beverage and develop behaviors and brain changes that are analogous to those produced by drugs of abuse in addition to a withdrawal syndrome similar to that induced by opioids. Artiga et al[81] described another model, a history of dieting and stress that induces binge eating behavior with palatable and nonpalatable foods. In that model, rats are subjected to cycles of food restriction and refeeding. For 5 d, they are administered only 66% of the standard diet given to control animals. For the next 2 d, animals have ad libitum access to chow and chocolate cookies, etc. The repetitive cycle is a good model to mimic what occurs in disorders like bulimia nervosa, as a prior history of energy deprivation is the most critical trigger of binge eating. The third program is the limited access model of Corwin et al[82]. It is a non-food-deprivation model in which rats have sporadic, intermittent, and limited access to high-fat food that allows an escalation of food intake to occur[83]. Eating in the absence of hunger is one of the most important characteristics of binge eating in humans, which demonstrates its hedonic nature[80,84].

Research on the link between binge eating disorder and vulnerability to drug addiction points to two main behavioral outcomes, cross-sensitization and the gateway theory[85]. The cross-sensitization phenomenon refers to the effects of bingeing on palatable foods, which leads to long-lasting neuroadaptations that increase the acute response to another drug. Early research in this area focused on the locomotor response to different drugs of abuse after exposure to different binge eating patterns. The majority of studies showed that animals developed a pattern of bingeing on palatable food, and exhibited enhanced locomotor sensitization to amphetamine[86,87] and cocaine[88-90]. These initial studies indicated that the compulsive behavior of bingeing on palatable food sensitizes the same system on which psychostimulants exert their action[86]. Intermittent access to palatable food promptly promotes a compulsion in intake and stimulation of the dopamine circuits in the nucleus accumbens that is sustained over time[62]. The response of the nucleus accumbens is similar to that observed after consumption of psychostimulants. Initially, when food is novel and palatable, dopamine levels in the shell increase, while those in the core are released independently of the reward’s novelty[91]. Avena et al[77] suggested that dopamine release derived from bingeing on palatable food is not subject to habituation, as it remains elevated even after repeated bingeing episodes.

After having shown that binge eating behavior induces increased sensitivity to the locomotor effects of psychostimulants, subsequent studies went further and investigated whether animals were also more prone to develop a substance use disorder, such as an increase in cocaine seeking and consuming. Most studies used operant self-administration (SA) and conditioning place preference (CPP) paradigms. The SA paradigm directly assesses a mouse's disposition to take the drug, as animals have to press a lever to experience the drug’s rewarding effect. The animal is free to choose to consume or not, and the paradigm directly measures motivation for the drug[92]. On the other hand, the CPP focuses on the role of contextual cues associated with the pleasurable effect of the drug. Mice associate a place or compartment with the rewarding experience of the drug and eventually develop a conditioned preference for that place[93]. Both paradigms provide a complete picture of what occurs in human addiction, when people consume to enjoy the pleasurable effects of the drug, but also because they find themselves in certain social contexts. These aspects play a crucial role in relapse into drug seeking.

To evaluate whether bingeing on palatable food alters an animal's disposition and motivation to take a drug, a 2011 study that used the limited access model of Corwin found a tendency toward an increase in intravenous cocaine SA, but the effect was not significant[94]. Consequently, we performed several mouse studies in our laboratory to further investigate this phenomenon, confirming that bingeing on fat during an early period of life, such as adolescence, enhanced intravenous cocaine SA and motivation to obtain the drug in adulthood[69]. We also used Corwin’s limited access model, in which adolescent mice had limited access to a high-fat chow for 2 h, 3 d/wk, with continuous access to a standard diet in their home cages. We observed an escalation in the intake of fat from the second week onwards, which confirmed the rapid development of fat bingeing behavior. Mice exposed to the high-fat binge sessions during adolescence showed an increase in cocaine SA compared with those fed a healthy standard diet. After acquiring a sustained cocaine SA, animals underwent an extinction process. When the operant behavior of pressing the lever to obtain cocaine was extinguished, mice were exposed once again to a single high-fat binge, which induced a strong reinstatement of the cocaine SA. Similarly, Barnea et al[85] observed that restricted access to a palatable diet was a risk factor for cocaine SA and drug craving and for binge eating state and trait, especially in the latter case. A binge eating state is induced by intermittent access to palatable diets, while the binge eating trait is a phenotypical proneness for overeating.

Regarding the key role of environmental clues in psychostimulant reward, a series of studies was performed in which animals that binged on fat during adolescence developed CPP for the drug-paired compartment, even with very low doses of cocaine[69] that were not effective in animals on a standard diet. The results confirmed that bingeing on fat increases sensitivity to the rewarding effects of cocaine and strengthens contextual memories associated with the pleasant experience.

Finally, palatable food can also induce withdrawal or craving for specific kinds of foods that are generally high in fat, salt, and sugar, much like that observed in drug addiction. For example, patients have described intense feelings of panic and anxiety when they are forced to postpone a binge eating episode or when they remove certain types of palatable food from their diet, leading to headaches, irritability, and anxiety[56,95]. Studies in animals also confirm that withdrawal symptoms are experienced when binge eating of specific kinds of food is stopped, confirming its potent effect on the brain[69,96,97]. The withdrawal-like symptoms common to cessation of any palatable diet arise following an increase in corticosterone and anxiety levels[98-100].

The effects of cessation of palatable food bingeing on the reward system have also been studied. For example, there is a significant increase in the locomotor response to cocaine after withdrawal from sugar[88,101]. Furthermore, animals that stop bingeing on fat are more resistant to forgetting the contextual memories associated with cocaine, and are more liable to relapse after lower cocaine doses[69]. All the studies suggest that bingeing on palatable food not only increases sensitivity to the rewarding effects of cocaine, but also heightens vulnerability to relapse into drug seeking.

CONCLUSION

Based on the literature published to date, we can conclude that the relationship between binge eating disorder and substance use disorders is a two-way street. On one hand, binge eating can be a risk factor or a gateway to drug addiction, and on the other, psychostimulant addiction can lead to several eating disorders. While we have referred to binge eating disorder throughout the review, binge eating may produce the same effects without necessarily meeting the diagnostic criteria for binge eating. In the same way as substance abuse, binge eating interferes with daily life and is characterized by persistence of the behavior despite the associated negative consequences, which include guilt, stress, and compensatory behaviors[6]. In relation to the binge cycle, an important common factor between eating disorders and drug abuse is relapse. Nair and colleagues[102] described how, on many occasions, people decide to diet and exercise, but that the resolve only lasts a few weeks, with a rapid return (relapse) of old (bad) habits. In that way, dieting induces changes in the reward system that can subsequently result in relapse into binge eating episodes and overeating.

In this review we have drawn a picture of bingeing on palatable food as something that is as harmful as substance abuse. If feeding is a risk factor that affects the same neurobiological mechanisms as drugs of abuse, early exposure to certain types of ultraprocessed food could be a gateway to increased sensitivity to reward. The high comorbidity that exists between the two disorders supports the hypothesis and highlights the importance of identifying and treating both conditions.

In the same manner that clinicians observe multiple nutritional deficiencies, anorexia and weight loss in cocaine abusers, which is described at the beginning of the review, the opposite effect can be observed after drug withdrawal[103]. Overeating during the rehabilitation phase is often recommended as part of detoxification programs as a way of counteracting craving. In this context, the concept of “addiction transfer,” where one addiction is replaced by another, has been proposed[104]. Indeed, increase in the rate of obesity among patients undergoing detoxification can be so dramatic that current substance addiction programs are beginning to complement treatment with physical exercise and diet programs to avoid it.

Most professionals focus on their area of expertise, resulting in the vital need for integrated services to deal with dually diagnosed patients who have a complex profile because of their substance use and binge eating disorders[105]. Until now, there have been no guidelines for experts to treat this comorbid condition. It is surprising that most specialists in substance abuse centers do not follow protocols that broach eating disorders among their patients. Likewise, most clinicians dealing with eating disorders are not trained to detect or investigate the possible misuse of substances of abuse.

Nutritional patterns should be considered an important variable in the treatment of people with substance use disorder, as an eating disorder may develop in parallel to detoxification from the drug, consequently affecting social relationships, cognitive functions, and lifestyle. Future studies should focus on specific treatments and interventions for individuals who have a special vulnerability to transfer from one addiction to another. It is now necessary to discover new therapeutic targets of food and drugs in order to improve public health solutions. In this context, new nutritional interventions are the focus of increasing investigation as possible modulators of reward and other diseases.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Substance abuse

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Raghow R S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo X