Published online Aug 19, 2021. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i8.403

Peer-review started: May 10, 2021

First decision: June 23, 2021

Revised: July 6, 2021

Accepted: July 15, 2021

Article in press: July 15, 2021

Published online: August 19, 2021

Processing time: 93 Days and 12.9 Hours

Suicidal behaviors in adolescence are a major public health concern. The dramatic rise in self-injurious behaviors among adolescents has led to an overwhelming increase in the number of those presenting to the emergency rooms. The intervention described below was constructed on the basis of brief and focused interventions that were found to be effective among suicidal adults using an adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents. The intervention has four main objectives: first, a focused treatment for reducing suicide risk; second, a short and immediate response; third, building a treatment plan based on understanding the emotional distress and interpersonal aspects underlying suicidal behavior; and lastly, to generate hope among adolescents and their parents. The intervention includes intensive five weekly sessions, followed by 3 mo of email follow-up.

Core Tip: Waiting time for treatment for adolescents who are at risk for suicide in Israel is unreasonably long. The purpose of the interpersonal psychotherapy based intervention for suicidal children and adolescents is to allow more children to receive an acute preventive intervention within a reasonable period of time. The initial phase includes building a safety plan, understanding the emotional and interpersonal aspects underlying the suicide risk and formulating a problem area. The middle sessions include learning and practicing emotional, behavioral and interpersonal skills. The termination session includes building a treatment plan for relapse prevention and providing hope.

- Citation: Klomek AB, Catalan LH, Apter A. Ultra-brief crisis interpersonal psychotherapy based intervention for suicidal children and adolescents. World J Psychiatr 2021; 11(8): 403-411

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v11/i8/403.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i8.403

Suicidal behaviors in adolescence are a major public health concern; recent elevation in adolescents suicidality highlight an increasing need for its prevention and treatment. The prevalence of non-fatal suicidal acts among children and adolescents is considerably high. In fact, suicide risk is the most frequent reason for presentation to psychiatric emergency rooms among this population[1]. Risk factors for suicide are numerous and utterly complex. Particularly, non-fatal self-injurious behaviors, which are generally recurring, constitute an especially elevated risk for suicide[2]. Unrecognized and/or untreated depression is the psychiatric disorder that is the most commonly associated with suicide[3]. Inappropriate management of depression may produce a range of adverse outcomes for children and adolescents, such as school failure and dropout, avoidance of friends, eating disorders, substance and alcohol abuse and of course the propensity to self-harm[3].

The dramatic rise in self-injurious behaviors among children and adolescents has led to an overwhelming increase in the number of those presenting to the emergency rooms worldwide[1]. In Israel each year, about 400 such incidents are accepted to our emergency room at Schneider Children’s Medical Center, with about a hundred of these cases necessitating subsequent treatment[4]. As a result, the average waiting time for treatment before the current study was about 12-18 mo; such a lengthy delay often culminated in deterioration of the child’s condition and led to an increased probability of adverse consequences. Evidently, the need to develop a brief and targeted intervention for this population is unequivocal. The need for emergency intervention has become even more important due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Many countries reported an increase in suicide rates among children and adolescents during this period[5]. Studies among suicidal adults have demonstrated the efficacy of brief and focused treatments in reducing suicide risk[6]. For example, receiving postcards from a clinic was found to reduce suicidal behaviors over time[7].

Interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A), a manualized, short-term (12 sessions) therapeutic intervention for adolescents with depression[8] is among the most common forms of therapy provided at our clinic. We decided to attempt to lessen the number of sessions even further in the hope of reducing our waiting list and enable a larger number of adolescents to receive therapeutic care. The rationale for selecting IPT-A specifically is based on present research linking interpersonal problems to suicide risk[9]. Previous studies found that individuals at risk for suicide suffer from significant challenges in their relationships[10]. Insecure attachment, in particular, has been identified as a major risk factor for adolescent suicidality[11]. In addition, difficulty expressing and sharing feelings with others has been found to significantly increase the risk of severe suicide attempts, above and beyond the contribution of depression and hopelessness[12].

IPT is a commonly used, evidence-based, time-limited treatment for depression in adults[13] and adolescents (IPT-A)[8,14] as well as other psychiatric disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders)[15]. IPT has demonstrated efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms and improving overall performance and social functioning[16]. IPT-A is an adaptation of IPT tailored specifically for adolescents with depression[8]. Similar to the original adult version, IPT-A is time-limited and evidence-based[8]. IPT-A focuses on addressing the link between depressed mood and current interpersonal problems. The goal of IPT-A is to reduce depressive symptoms and improve interpersonal function

Recently, a number of studies documented the potential for effectiveness of IPT in treating suicidal patients. Mufson et al[17] presented preliminary outcomes of a small sample of suicidal adolescents treated with IPT-A (IPT-A-Suicide Prevention). Tang et al[18] examined the effects of intensive interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents with depression who were at risk for suicidal behavior and compared these adoles

To the best of our knowledge, despite the tremendous service gap and devastating consequences of the global suicide epidemic among children and adolescents, no protocol exists that offers a very short, practical and feasible crisis intervention for children and adolescents who are at risk of suicide. The intervention described below was constructed on the basis of brief and focused interventions that were found to be effective among suicidal adults using an adaptation of IPT-A.

The efficacy of IPT based intervention for suicidal children and adolescents has been recently published elsewhere[4]. The following is a thorough description of the intervention itself. The intervention has four main objectives: first, a focused treatment for reducing suicide risk; second, a short and immediate response to be able to deliver the intervention within a month from the date of referral; third, building a treatment plan based on understanding the emotional distress and interpersonal aspects underlying suicidal behavior and the associated, distinct difficulties of the patient (such as interpersonal skills deficits and emotion dysregulation); and lastly, to generate hope among patients and their parents. Our assumption is that achieving these four goals allows the patient and parents to feel that things can get better, which in turn helps to decrease the patient’s suicide risk.

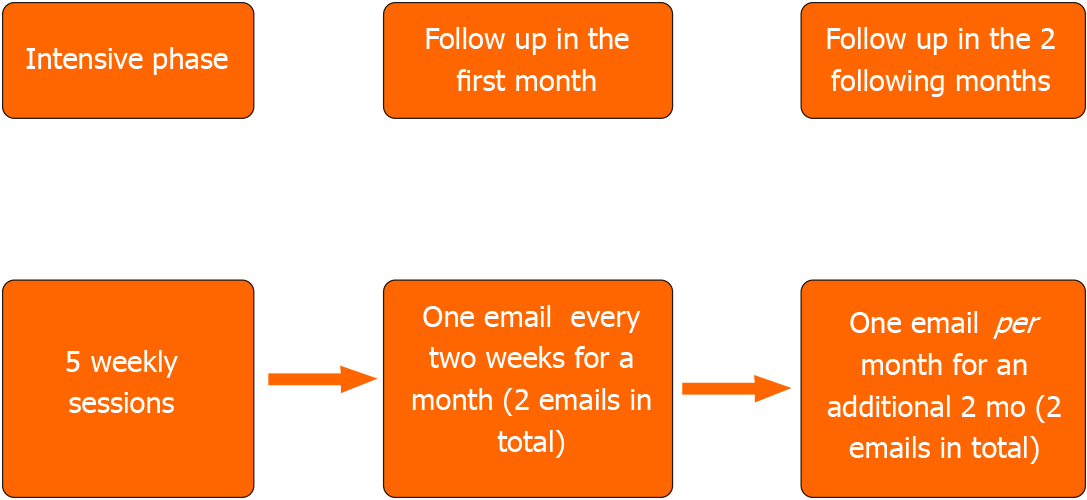

The intervention is comprised of an intensive phase of five weekly sessions and a follow-up phase consisting of four emails across a 3 mo period. The emails are sent to both the adolescent and his/her parents. In the first month post-intervention, two emails are sent (one email every 2 wk). In the following 2 mo, two additional emails are sent (an email every month) for a total of four follow-up emails (Figure 1).

Parental involvement: The intervention is intended for children and adolescents ages 6-18-years-old. We require parental attendance at the first and final sessions and invite parents to attend additional sessions as needed. For children under 10 years of age we recommend that the parents be present during all five sessions.

The intensive phase: The intensive phase is based on IPT-A with the addition of some elements adapted from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention[19] and Dialectical Behavioral Therapy[20].

The first and second sessions constitute the initial phase of the acute intervention and involve assessment and diagnosis of depression and suicide risk (risk assessment), interpersonal assessment and problem area formulation. The third and fourth sessions comprise the middle phase of the acute IPT-A intervention, which focuses on fostering emotional and interpersonal skills within the specific problem area. The termination phase includes the final fifth session in which the patient and therapist summarize the therapeutic process, and the therapist provides recommendations for further treatment. Below is a detailed description of each session.

The first session should ideally include both patient and parents to establish initial rapport and commitment as well as focus on depression and suicidal risk. It is an especially intensive meeting requiring an active therapeutic approach and should include:

(1) Risk assessment: A short risk assessment is conducted in addition to the initial risk assessment generally conducted at the intake. This portion of the first session includes an evaluation of depressive symptoms using scales like the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire[21] as well as an assessment of suicidality based on the Columbia Suicide Rating Scale[22] and/or Suicide Ideation Questionnaire[23].

(2) Safety plan[24]: In the event of suicidal risk, an interpersonal safety plan is constructed in collaboration with the patient and the parents. The safety plan includes a list of coping strategies arranged in a hierarchical order, available for the patient, should a suicidal crisis occur. The main purpose of the plan is to provide a predetermined course of action for potential coping strategies as well as a list of specific and relevant support resources. The plan includes internal strategies that a patient employs on his own (e.g., self-talk) in addition to a list of contacts of individuals in the patient’s life (e.g., family members, healthcare providers) who can be contacted in real time to help reduce the risk of suicidal behavior. A collaborative approach is recommended between the therapist, the patient and the parents. The plan is a dynamic therapeutic program reviewed periodically by the patient and therapist to evaluate the need for any particular changes or additions.

(3) Chain analysis: A chain analysis is performed in order to outline and discern the events that occurred in the hours prior to the attempt. The chain analysis allows for better understanding of the context of the suicidal act and the emotional and interpersonal/social triggers preceding the attempt.

(4) Presenting the intervention to adolescents and their parents: A thorough explanation of the nature, structure and goals of the intervention is presented to the adolescent and parents. The need for parental cooperation is addressed directly, and the topic of confidentiality is discussed. Further, the obligation to share details of the patient’s risk and needs with the school is discussed. The goal of collaboration with the school is to increase the support the patient receives from the school in the areas he struggles the most (e.g., academic, social or emotional realms). Although the communication with the school is addressed in the first session, in practice the school is contacted only after the end of the second session, once we have gotten to know the patient better and have jointly delineated with the patient the main problem area that underlies his/her suicidality. Finally, the limitations of the intervention and the need for long-term psychological treatment and/or consultation about psychotropic medication are addressed. The family is accompanied throughout the intervention in the challenge of finding appropriate follow-up care after the acute IPT-A for suicidal children and adolescents intervention.

and (5) Psychoeducation: Extensive psychoeducation about depression, suicidality, adolescence, parenting and other patient-specific topics is provided. The patient is presented with an explanation of the concept that suicidal crises come in waves and that the purpose of the intervention is to prepare for the next wave. The underlying assumption is that it is likely there will be more crises in the future even if, at the moment, the patient is feeling better. We also use the IPT-A concept of a “Limited Sick Role,” which is an aspect of the medical model of IPT. This role refers to the need to match expectations between functional requirements and the patient’s mood. The patient is encouraged to function to the best of his ability, while adjusting the pace and progress to his mental state. The concept of the limited sick role is also explained to the patient’s parents and teachers.

Each session begins with an evaluation of the patient’s mood and suicidal risk on a scale of 0-10 and discussion about the changes needed in the safety plan. While the first session focuses on the depression and suicidal risk, the second session concentrates on interpersonal functioning. The purpose of the second session is to define the problem area that will be the main focus of the intervention. In order to achieve this, the therapist uses the Closeness Circle and the Interpersonal Inventory[25]. The Closeness Circle is a series of circles, one inside the other (Supplementary material 1). The therapist explains that the circles around the patient’s name represents circles of closeness, and the goal is to place the patient’s significant relationships within the appropriate circles according to the relevant degree of intimacy; the result is a visual representation of the patient’s significant relationships. Then, the therapist and the patient discuss the patient’s meaningful relationships using the Interpersonal Inventory. The Interpersonal Inventory includes questions related to facts, opinions, particular events and feelings about the relationships with the people outlined in the patient’s circles. The goal of this session is to reach as deep of an understanding as possible of the patient’s emotional and interpersonal world and to identify the most relevant emotional and interpersonal struggles that may be the underlying issues contributing to the patient’s suicidal risk.

The first two sessions lead to the formulation of the main problem area that the patient is currently dealing with[25]. The problem area is a framework in which the patient and therapist learn and practice skills in the middle phase of the intervention. The line of questioning taken by the therapist in exploration of the various potential problem areas (e.g., grief, conflicts, role transitions and interpersonal deficits) should be directed towards obtaining relevant information in order to ascertain which is currently most significant. There are four main problem areas: (1) grief: relates to actual death and refers to situations in which depression developed due to compli

During or after the second session, the therapist contacts and communicates with the school staff.

These sessions are focused on fostering and practicing interpersonal, emotional and behavioral skills. Each session begins with an examination of the patient’s mood during the past week as well as his suicidal risk. The safety plan is reviewed and readjusted. These two sessions focus on skills learning and practicing within the formulated problem area.

As there is very little time within this brief intervention for skill learning, the therapist should choose one or two IPT-A skills that the patient exhibits the greatest deficits in and that are most relevant to his suicidal risk. These skills are typically related to mood and/or interpersonal relationships. There are three skill sets to choose from including emotional, behavioral and interpersonal. Emotional skills include an emphasis on emotional regulation techniques. The work on emotions with these at-risk children and adolescents include raising their awareness to the various emotions, cultivating their ability to label their emotions, monitoring their intensity and learning ways to regulate them in order to control behaviors associated with these feelings. This promotes the patient’s realization and understanding that it is normal to feel lonely, sad or hopeless at times. Yet, when these emotions are intensive and overwhelming, the adolescent should act to control their behavior. Behavioral skills include decision analysis (interpersonal problem-solving), which are crucial in every type of interpersonal interaction. Lastly, enhancement of interpersonal skills incorporates communication analysis, in which the patient learns to identify maladaptive communication skills and learns flexible and adaptive alternatives. All skills are taught through role-play and entail interpersonal experiments intended to be conducted between sessions (i.e. in real life) and processed with the therapist during the sessions themselves. Many of the parents benefit from these skills training as well and are therefore encouraged to attend these sessions as needed.

The concluding session of the intensive phase includes a summary of the interpersonal and emotional work that has taken place and recommendations for further treatment. In this session we re-emphasize that suicidal risk and behaviors occur in waves and address the possibility that the adolescent may feel suicidal again by discussing relapse prevention. We return to the safety plan devised together in the beginning of treatment in order to ensure its relevance and verify that the patient is familiar with it and willing to use it when needed.

Following the intensive phase, periodic emails are sent to the patient and his parents over a 3 mo timespan. During the first month following termination, an email is sent every 2 wk. Then, during the following 2 mo, one email is sent each month. The emails are sent to the patient’s personal e-mail and/or his parent’s email depending on the patient’s age and preferences.

The email is written in a fixed format and is sent directly from the clinic. The email includes patient-specific information in order for it to be personalized (Supplementary material 2).

Rona (pseudonym) is a 16-and-a-half-year-old, 11th grade student. She lives with her parents and two brothers in a city in the center of Israel. Her father is a software engineer, and her mother works as a teacher. Both parents were born in the Soviet Union and immigrated to Israel in their early 20s.

Rona presented with a significant suicide attempt in which she swallowed 50 pills with an intention to die. The psychiatric evaluation concluded that she was diagnosed with depression. She began anti-depressant medication and was simultaneously referred for IPT-A for suicidal children and adolescents.

Assessment and psychoeducation: The first session took place with Rona and her parents. After taking Rona’s history, psychoeducation was provided, focusing primarily on symptoms of depression and suicide prevention. Further, the intervention itself was explained in terms of its structure, content and goals and the need to find continued, psychological care post-treatment even though we just started.

The next step was performed with Rona alone. A clinical evaluation of depressive symptoms and suicidal risk was repeated, and Rona completed a few self-report questionnaires. In the clinical assessment, Rona denied current suicidality. She stated she understood she had made a mistake attempting suicide and declared she would avoid future attempts. She denied suicidal ideation and intent to die. She also reported significant improvement in her depressive symptoms. Her questionnaires indicated significant depression (Mood and Feelings Questionnaire = 29), moderate severity of suicidal ideation (Suicide Ideation Questionnaire = 33) and high suicide risk (Columbia Suicide Rating Scale = 5).

Safety plan: The next step included a collaborative drafting of a safety plan with Rona. Although Rona insisted it was unnecessary, the need to build a plan for handling potential suicidal waves was explained to her. Rona was cooperative, and the program seemed to be a good fit for her (Supplementary material 3). Despite the proper plan and the fact that Rona denied suicidal risk, we kept in mind the immense gap between the current circumstances and the serious suicide attempt she had made just a month prior to her referral. A substantial portion of the present therapeutic intervention focused precisely on this gap.

Chain analysis: From the chain analysis it became evident that the night before the suicide attempt, Rona was very stressed because of an exam she was supposed to take the next day at school. She knew that she had not studied properly and was extremely afraid that she would fail. She felt that she could not afford to fail this exam especially because she knew how much her failure would disappoint her father.

She tried not to think about it and watched TV, but she could not concentrate. She only imagined the reaction of her father when he finds out that she failed the exam. She was not able to sleep all night. When the day started the pressure increased, and there seemed to be no other solution. She felt stressed and helpless. She got ready for school as if she were planning on going, her parents wished her luck on the exam and left for work. She was left alone at home and finally decided she was not going to go to school. She felt desperate. She went to her shower and saw a packet of pills. She felt that she would rather die than face whatever would happen if she went on with her day as planned. She took all the pills in the container. Her mother found her half an hour later, in the bath with the pills next to her. When Rona recovered in the hospital and saw her parents, she was very disappointed to find that she was still alive and felt awfully guilty and ashamed.

After we conducted the chain analysis, we came back to the safety plan and addressed the need to use it whenever stressful events occur. Towards the end of the session, we invited the parents to rejoin and shared with them the safety plan; we clarified what was required from them when Rona approaches them in times of crisis.

The second session focused on the interpersonal assessment; to enhance this process we used the Closeness Circles and the Interpersonal Inventory. Rona had many people in the circles (Supplementary material 1), and it seemed she had many significant individuals in her life. She described close and meaningful relationships with her friends, juxtaposed to the fact that she recently moved away from them. Her father was in the closest circle to her. She described a special and close relationship with him that was different from her father’s relationship with her brothers. She explained that her academic success was always important to her father and that when she was younger, he tutored her for many hours. However, Rona explained she was not invested in her studies and preferred to spend time with her friends; she described ongoing conflicts between her and her father about it. Rona felt that her dad did not understand her needs. In the last year she was less invested in her studies, and this negatively impacted her relationship with her father. Rona felt he was dissatisfied with her and believed he was distancing himself from her. She felt that the two were no longer as close as they used to be. Rona shared that she missed the closeness they had, and she felt she failed to be the daughter her father wanted her to be. Further, Rona shared her parents’ relationship was deteriorating and that they quarreled often. In the past, Rona’s father had shared with her some of his feelings about her mother, and Rona felt that she understood her father better than her mother did. She missed being the one her father trusted and confided with.

Rona’s mother was in the second circle. Rona describes she was never very close to her mother and felt that her mother was unable to truly understand her. Rona described she did her best to help around the house whenever her mother asked her to, which she felt helped avoid arguments with her mother and assisted in maintaining a somewhat normal relationship between the two of them. There was no real closeness between Rona and her mother, but Rona insisted it did not bother her and that their relationship was this way as long as she could remember. The more we talked about their relationship, the more likely it seemed that Rona actually wished to be closer to her mother but that she was too afraid to expect intimacy with her and be disappointed.

In the third circle Rona wrote her ex-boyfriend. Rona shared she decided to break up with him 2 mo ago because she felt she was no longer fun to be around and that she would probably disappoint him soon as she disheartened others in her life. She felt she was changing; she was no longer in the mood to hang out with friends and found she mostly preferred to be alone. After the interpersonal inventory, we introduced Rona to the concept of problem areas and collaboratively chose the problem area of interpersonal disputes (surrounding her conflicting relationship with her father).

Learning skills: The third and fourth sessions focused on skill acquisition and rehearsal. The goal was to teach Rona skills that would help her communicate better with her father (communication skills) as well as skills that would help her respond differently if she felt similarly to how she felt prior to her suicide attempt (emotional regulation skills). We used communication analysis and identified the need to work on Rona’s ability to speak more openly with her father and express her feelings to him without fearing she would be disappointing him. Through communication analysis we were able to uncover that Rona predominantly avoided discussing her school difficulties with her father or share with him that she wished to be more engaged in other activities such as spending time with her friends.

Together, we brainstormed some goals Rona wished to achieve in a potential conversation with her father. Rona wanted to relieve stress from her studies and accomplishments without feeling she would be disheartening her father too much. We planned numerous possible scripts for the conversation and used the teen tips to promote effective communication. Between sessions, Rona practiced her commu

Further, sessions centered on fostering Rona’s emotional regulation skills. At first, Rona found it difficult to recognize the feelings she experienced before attempting suicide (e.g., the fear of disappointing her father, hopelessness and loneliness, in particular). She was only able to describe she felt she was “under pressure.” Through processing Rona’s feelings prior to the attempt, we were able to elucidate Rona’s explicit fear of disappointing her father, which led her to distance herself from him initially and avoid others subsequently, the latter behavior culminating in a detrimental increase in her feelings of loneliness and sadness. Between sessions Rona was requested to monitor the intensity of her negative emotions in various situations, and together we practiced numerous self-calming methods such as self-talk and relaxation techniques. Further, Rona was asked to practice additional soothing techniques at home, and these skills were added to her safety plan. Our intention was to teach Rona to recognize situations in which she would be likely to have a decreased ability to regulate her emotional state, so that once becoming aware of them she would have adaptive means of calming herself.

As described above, the objectives of the fifth session are to summarize the therapeutic process, focus on relapse prevention, provide recommendations for further treatment and review the safety plan. The meeting was divided into two parts; in the first half of the meeting we met Rona alone, and her parents joined us in the second part of the session. We addressed the focus of Rona’s difficulties, her experiences and her needs in the relationships with her parents. Her parents were invited to express their desire for closeness in addition to their concern for her well-being. We repeated and reevaluated the safety plan with Rona and later with the parents to ensure each of them was knowledgeable of what to do should Rona feel suicidal again.

Although the need for continuous treatment for Rona had been discussed earlier in treatment, present difficulties of finding available individual psychotherapy in the community disabled her immediate transition into follow-up care. Rona was waitlisted for long-term treatment at our clinic, and in the meantime, the family began family therapy.

At the end of the intervention, there was a significant reduction in Rona’s depressive symptoms, and she continued to deny current suicidal ideation. The family remained in family therapy for 8 mo, and treatment was found to be helpful and led to tremendous therapeutic gains. A year later, Rona began long-term treatment at our clinic. Of note, throughout this period, Rona refrained from further engagement in suicidal behaviors.

| 1. | Zanus C, Battistutta S, Aliverti R, Montico M, Cremaschi S, Ronfani L, Monasta L, Carrozzi M. Adolescent Admissions to Emergency Departments for Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bilsen J. Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Front psychiatry. 2018;9:540. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mullen S. Major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Ment Health Clin. 2018;8:275-283. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Haruvi Catalan L, Levis Frenk M, Adini Spigelman E, Engelberg Y, Barzilay S, Mufson L, Apter A, Benaroya Milshtein N, Fennig S, Klomek AB. Ultra-Brief Crisis IPT-A Based Intervention for Suicidal Children and Adolescents (IPT-A-SCI) Pilot Study Results. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:553422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hill RM, Rufino K, Kurian S, Saxena J, Saxena K, Williams L. Suicide Ideation and Attempts in a Pediatric Emergency Department Before and During COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020029280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 48.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gysin-Maillart A, Schwab S, Soravia L, Megert M, Michel K. A Novel Brief Therapy for Patients Who Attempt Suicide: A 24-months Follow-Up Randomized Controlled Study of the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP). PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Motto JA, Bostrom AG. A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:828-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mufson L, Dorta KP, Moreau D. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. 2nd ed. New York: Guildford Press, 2004. |

| 9. | Jacobson CM, Mufson L. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents adapted for self-injury (IPT-ASI): rationale, overview, and case summary. Am J Psychother. 2012;66:349-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Joiner T, Kalafat J, Draper J, Stokes H, Knudson M, Berman AL, McKeon R. Establishing standards for the assessment of suicide risk among callers to the national suicide prevention lifeline. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:353-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Falgares G, Marchetti D, De Santis S, Carrozzino D, Kopala-Sibley DC, Fulcheri M, Verrocchio MC. Attachment Styles and Suicide-Related Behaviors in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Self-Criticism and Dependency. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Horesh N, Levi Y, Apter A. Medically serious versus non-serious suicide attempts: relationships of lethality and intent to clinical and interpersonal characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:286-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Markowitz JC, Weissman MM. Casebook of interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychology. 2012;. |

| 14. | Brunstein-Klomek A, Zalsman G, Mufson L. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (IPT-A). Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2007;44:40-46. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Mahan RM, Swan SA, Macfie J. Interpersonal Psychotherapy and Mindfulness for Treatment of Major Depression With Anxious Distress. Clin Case Stud. 2018;17:104-119. |

| 16. | Spence SH, O'Shea G, Donovan CL. Improvements in Interpersonal Functioning Following Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) with Adolescents and their Association with Change in Depression. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2016;44:257-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mufson LH, KP DortaC, M Olfson, MM Weissman, K Hoagwood. Effectiveness Research: Transporting Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A) From the Lab to School-Based Health Clinics. Clin Child Family Psychol Rev. 2004;7:251-261. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tang TC, Jou SH, Ko CH, Huang SY, Yen CF. Randomized study of school-based intensive interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents with suicidal risk and parasuicide behaviors. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:463-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stanley B, Brown G, Brent DA, Wells K, Poling K, Curry J, Kennard BD, Wagner A, Cwik MF, Klomek AB, Goldstein T, Vitiello B, Barnett S, Daniel S, Hughes J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:1005-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;3:3631-3634. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:726-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2377] [Cited by in RCA: 3637] [Article Influence: 242.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Reynolds W. Suicide Ideation Questionnaire. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987. |

| 24. | Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19:256-264. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 574] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 51.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron E. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. New York: Basic Books, 1984: 379-395. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Israel

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kotzalidis GD S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo X