Published online Nov 19, 2021. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i11.1053

Peer-review started: May 7, 2021

First decision: June 5, 2021

Revised: June 10, 2021

Accepted: August 30, 2021

Article in press: August 30, 2021

Published online: November 19, 2021

Processing time: 193 Days and 19.2 Hours

Phantom bite syndrome (PBS), also called occlusal dysesthesia, is characterized by persistent non-verifiable occlusal discrepancies. Such erroneous and unshakable belief of a “wrong bite” might impel patients to visit multiple dental clinics to meet their requirements to their satisfaction. Subsequently, it takes a toll on their quality of life causing, career disruption, financial loss and suicidal thoughts. In general, patients with PBS are quite rare but distinguishable if ever encountered. Since Marbach reported the first two cases in 1976, there have been dozens of published cases regarding this phenomenon, but only a few original studies were conducted. Despite the lack of official classification and guidelines, many authors agreed on the existence of a PBS “consistent pattern” that clinicians should be made aware. Nevertheless, the treatment approach has been solely based on incomplete knowledge of etiology, in which none of the proposed theories are fully explained in all the available cases. In this review, we have discussed the critical role of enhancing dental professionals’ awareness of this phenomenon and suggested a comprehensive approach for PBS, provided by a multidisciplinary team of dentists, psychiatrists and exclusive psychotherapists.

Core Tip: Generally, in dentistry, uncomfortable occlusal sensations are a common finding among patients while phantom bite syndrome (which is distinguishable if ever encountered) is quite rare. These patients present with non-verifiable occlusal discrepancies with strict demands for bite correction and remarkable psychological distress. This might lead to serious consequences on patients’ life quality, relationship with family, financial loss, career disruption or even suicidal thoughts. Recent studies have revealed unexplained diversity patterns among phantom bite syndrome’s clinical manifestation and functional brain imaging, which likely represent the available sub-phenotypes of this syndrome. Further research must be focused on elucidating pathophysiological mechanisms to pave the way for efficient treatment strategy.

- Citation: Tu TTH, Watanabe M, Nayanar GK, Umezaki Y, Motomura H, Sato Y, Toyofuku A. Phantom bite syndrome: Revelation from clinically focused review. World J Psychiatr 2021; 11(11): 1053-1064

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v11/i11/1053.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i11.1053

A general dentist might come across many patients with disturbing or uncomfortable bite sensations in their daily practice. Most of the time, these typical complaints are due to reasons such as new crown delivery, dental restorations, orthodontic treatment and temporal mandibular joint dysfunction. Subsequently, dentists will perform some occlusal adjustments or provide a specific therapy, if on examination they observed any abnormal intercuspation or contact patterns. However, apart from these ordinary cases, there are some cases where patients present with non-verifiable occlusal discrepancies with strict demands for bite correction.

This phenomenon, named “phantom bite syndrome” (PBS), was firstly described by Marbach in 1976 with a report of two female cases[1,2]. The term was originally inspired by phantom limb pain, because it was suggested that what occurred after dental treatment in patients with hypochondriacal or severe personality disorder resembles the “ego defense” or “denial of loss” mechanism in postamputation patients[2]. Earlier, Posselt had mentioned this unusual sensation as a hyperawareness named “positive occlusal sense” in his textbook from 1960, saying “after occlusal grinding or adjustment, some person with a nervous predisposition may become too conscious of their own occlusion”[3]. However, Marbach’s evocative illustrations are useful for clinicians to visualize better the phenomenon.

In 1997, Clark et al[4] proposed an alternative term: “Occlusal dysesthesia”. Nowadays, this is commonly used to define “a persistent (more than 6 mo) uncomfor

Generally in dentistry, uncomfortable occlusal sensations are a common finding among patients, while PBS (which is distinguishable if ever encountered) is quite rare. According to an email survey sent to United States orthodontists, 75% of respondents recalled encountering at least one patient with typical symptoms of phantom bite during their career, even though almost half of them were unfamiliar with the term itself[6]. Gerstner et al[7] in their study found that 20.5% of 127 temporal mandibular disorder (TMD) clinic patients had their uncomfortable bite all the time. However, whether their “discomfort” met the PBS diagnosis criteria was not discussed. In a study by Watanabe et al[8], PBS only accounts for less than 10% of outpatients who visit a specialized clinic of oral psychosomatic disorders. The discrepancy of the ratio between cases encountered by United States orthodontists and the cases in specialized clinic might be attributed to their obsession for “ideal bite correction” as mentioned above. Yet, to our knowledge, there has been no study that estimates the incidence of this phenomenon in the general population.

Back in 2012, there were no original PBS data published. Hara et al[9] were the first to combine the results from 37 case reports in their first systemic review. Later, in two retrospective studies done by two different Japanese teams, the data confirmed similar patterns of female predominance, mean age and symptom duration. In particular, the female ratio varies from 72% to 84%, while the mean age at the initial visit ranges from 51.7 years to 53.1 years[8,10]. In terms of symptom duration, 39.5% of patients suffered from an abnormal bite for more than 5 years[8]. Except for the 2 cases that started since adolescence (as both described by Marbach), the majority developed their onset symptom around the age of 45[2,9].

One frequent observation among many PBS cases is that the first mild discomfort is often associated with some certain dental treatment (e.g., restorations, orthodontic treatment), then it becomes worse after further occlusal adjustment or extensive dental interventions (e.g., replacing crowns, extraction)[2,8,11-17]. However, 26.2% of 130 PBS patients reported symptoms that developed spontaneously or with triggers other than dental therapy. Looking for an ideal bite correction, they then visited approximately 4.4 ± 3.4 dental clinics[8]. The highest record belongs to one male patient who attended at least 200 appointments with 20 different dentists in 6 years[11]. To be able to pursue such a frustrating, time and money-consuming journey, the PBS patients are normally assumed to be of moderate to high socioeconomic status[11,15,18]. Such impression comes from expert consensus, but in fact, the situation may vary depending on national medical systems and policy.

In the very first announced case, Marbach suspected that PBS patients were mentally ill with delusion and paranoia, saying “hope for these unfortunate patients lies in part in the ability to make psychiatric research available for dentists”[2]. This argument was questioned later by Greene and Gelb, when 4 out of 5 patients in their report did not qualify for any diagnosis of mental disorders[19]. From a Japanese prosthodontist’s report, 46.2% of the patients complaining of occlusal disharmony had neuroticism, and 53.8% had manifest anxiety[20]. This aligned with recent reports whose prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity (depression, anxiety disorder, insomnia, somatic symptom disorders) was between 45.9% and 59.51%. Schizophrenia and severe personality disorders were rare[8,10]. Since PBS patients mainly complain of occlusal discomfort and rarely present severe psychiatric comorbidities, they seldom are provided active psychiatric treatment.

Despite the lack of official classification and guidelines, many authors agreed on the existence of a PBS “consistent pattern” that clinicians could easily recognize and should be made aware[9,18,21,22]. A list of frequently observed clinical manifestations is summarized in Table 1.

| Clinical characteristics | |

| 1 | Preoccupation with their dental occlusion and an enormous belief that their dental occlusion was abnormal |

| 2 | A long history of repeated dental surgery treatment failures with persistent requests for the occlusal treatment that they are convinced they need |

| 3 | A relatively high intelligence and socioeconomic status enabled them to undergo endless costly and time consuming dental treatments |

| 4 | Despite repeated failures of dental surgery, persist in seeking bite correction from a succession of dentists |

| 5 | A strong resistance to referral to psychiatrists and stick to dental procedures |

| 6 | A favorable attitude to dentists at first, gradually blaming them for the exacerbated symptoms, finally dropping out with disappointment |

| 7 | A tendency to use dental jargon |

| 8 | Bringing to the appointment pieces of evidence to prove occlusal discrepancies (radiographs, study cast, temporary crowns, mouthpieces, etc.) |

Firstly, the occlusion or bite would be the center of their complaints, even though they may be expressed in many different ways (see Table 2). This would make PBS distinguishable from other oral conditions characterized by abnormal sensations or idiopathic pain without evident causes such as burning mouth syndrome, oral cenestopathy and atypical odontalgia. Besides, PBS could be observed together with TMD and is sometimes even categorized as TMD’s subgroup[5,23-25].

| Terminologies |

| Phantom bite syndrome |

| Occlusal dysesthesia |

| Occlusal hyperawareness |

| Occlusal hypervigilance |

| Occlusal neurosis |

| Positive occlusal sense |

| Persistent uncomfortable occlusion |

| Frequent complaints |

| Abnormal/uncomfortable bite |

| My bite is off/too high |

| My jaws are not biting correctly |

| Jaw looseness and weak bite |

| Uneven dental bite |

| Feel uneasy with the bite |

| I try maneuver to position the bite correctly |

| I don’t know where my teeth belong anymore |

| Lack of familiarity with my own bite |

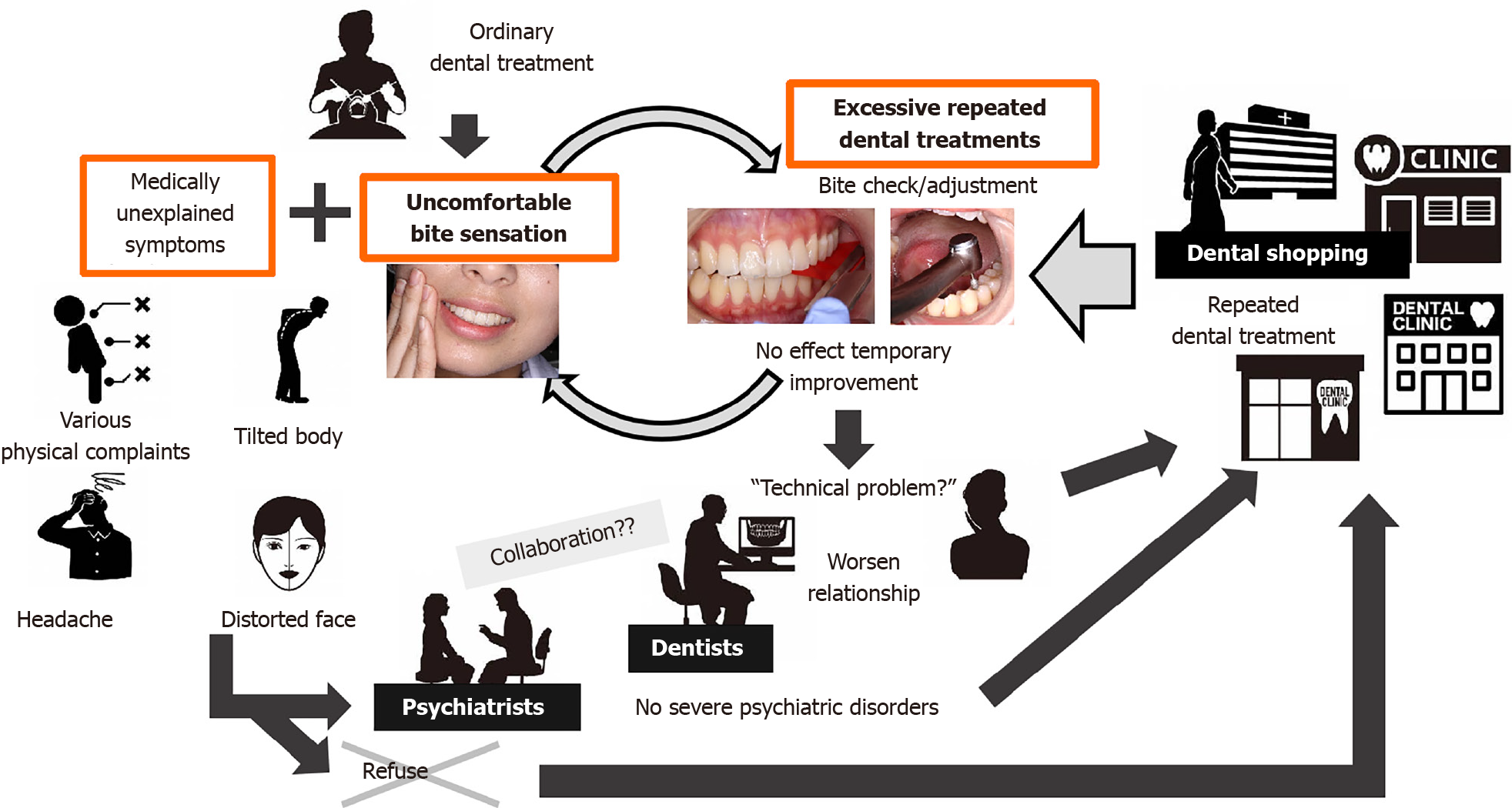

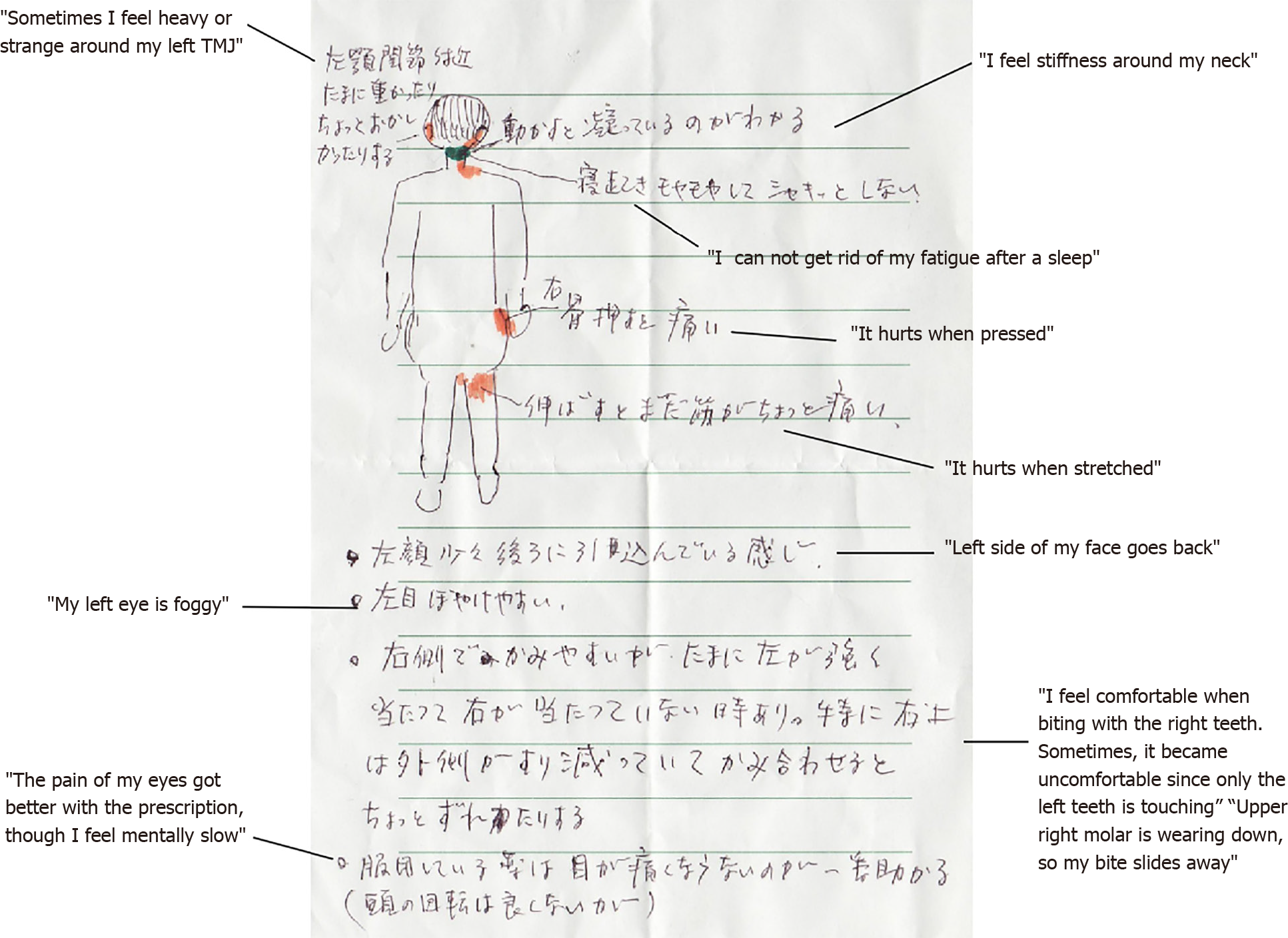

Another important clinical aspect rarely mentioned in the literature is patients’ emphasis that their occlusal problems lead to concomitant somatic symptoms in other body parts (e.g., idiopathic headache, musculoskeletal pain)[8,11,12,16,22,26]. “Our teeth is not separated from the body, after all”, one patient even said[2]. Therefore, they firmly believe that all of their somatic dysfunctions would be cured if and only if their bites are corrected (Figure 2).

There has been no official record of specific triggers other than dental interventions at symptom onset. However, some cases reported patients who experienced a traumatic accident or underwent a pressured period of life (e.g., divorce, change of jobs), with or without dental treatments[8,12]. Lack of a dental trigger becomes a predictor for psychiatric comorbidity, which affects the treatment outcome[8].

When patients describe their symptoms, they tend to use dental professional terminologies, even when they only have superficial knowledge about their conditions[2,11,13]. Not only equipping themselves with a lot of arguments and self-research information, they often bring to the appointment pieces of evidence to prove occlusal discrepancies, including their collection of diagnostic casts, occlusal splints, teeth pictures, radiographs or even extremely detailed resume and records from previously failed treatments[2,6,11,18,26,27]. They would, sometimes, describe clearly and confidently that prior incompetent dentists are responsible for their exacerbated symptoms[2,6,11,13,15,28].

From our clinical observation, some patients are more obsessed with the idea of getting their occlusal equilibrium done than the “wrong bite” itself. In many cases, PBS patients even rigorously direct the dentists on what to be done. If not granted desired treatments, these patients would reject any other suggested treatment and quickly drop out after the first or second visit. Once the dentists recognize this pattern, inform patients about their normal examination results and gently recommend another specialist/psychiatric assessment, this rational approach will be met with prolonged discussions and denial. Meanwhile, even if patients’ demands are met, the absence of any tangible result will reinforce the existing erroneous belief that the occlusion problem has not been properly addressed. Dental services often affect PBS patients iatrogenically for worse (Figure 3). Such a vicious cycle of dental shopping thus continues.

In terms of psychological impacts, a study by Tsukiyama et al[29] showed significantly higher scores of somatic symptoms and depression subscales in PBS patients in comparison with those of control groups. Nevertheless, as the author self-declared, these differences “only indicate that the patients may have psychiatric problems, not possible to prove that they have mental disorders”. Even in PBS cases without psychiatric comorbidity, psychological distress is remarkable. They might lead to serious consequences on patients’ life quality, relationship with family, financial loss, career disruption or even suicidal thoughts[2,11,12,15]. Corresponding dentists, if trapped in these unusual cases, will quickly find these patients oppose any treatment and become increasingly challenging to manage. The worst scenarios would be litigation problems between patients and dentists[2,11,13].

Initially, PBS was viewed as a psychotic disorder that was “rarely brought to the attention of psychiatrists” before being classified into monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis (MHP)[2,18]. This speculation arises from the similarity between “wrong bite” obsession in PBS patients and “an erroneous and unshakable belief in a distorted body image” in MHP phenomenon[18]. In other words, PBS was suggested to be a sub-phenotype of MHP present in dental clinics, comparable with parasitosis that is often seen by dermatologists, sharing the common features of equal gender distribution and early adulthood onset. Unfortunately, this observation seems no longer to concur with recent demographic reports[8-10].

Twenty years later, this “psychodynamically oriented view” is replaced by the same author[30]. At this time, Marbach[30] adapted Melzack’s theory of neuromatrix and re-discussed PBS’s pathophysiology in a shared context with phantom tooth pain/atypical odontalgia[30,31]. The key element of this theory is that there exist individual differences in self-knowledge of occlusion, namely occlusal neurosignature. Such a unique coherent unit in the brain was created and is influenced by lifetime intercuspation and other tooth contacts. Whenever a dental intervention or routine adjustment is made, it would send a new input to the central nervous system. In the case of PBS patients, it is difficult for their neuromatrix to adapt to even a minor change, and they thus soon become unable to recognize the original bite itself[30].

From 1993 to 2000, Toyofuku[32] conducted a clinical study using psychosomatic approaches to treat 16 serious PBS cases during hospitalization. As a result, it was observed that 15 of 16 PBS patients responded to the combination therapy of tricyclic antidepressants and supportive psychotherapies. From the result of these clinical observations, the author hypothesized that PBS might be due to several biochemical disorders involving neurotransmitters in the brain, the wrong connection between occlusion and medically unexplained complaints due to cognitive processes in the higher centers of the brain. This working hypothesis, however, had not been recognized widely due to the language barrier of Japanese publications. Notably, in the follow-up study 5 years later, about one-third of these cases began to complain of request for needless dental treatments again. Besides, a review of 130 PBS patients suggested that PBS is seldom associated with psychotic disorders. Central neuromodulator (antidepressant or antipsychotic) therapy may be effective for PBS. Most of these medications were given at very low "non-psychiatric" doses”[33]. These findings support the working hypothesis, suggesting the role of biochemical disorders involving neurotransmitters in the brain of PBS patients.

In 2003, Clark and Simmon[5] proposed the theory of altered oral kinesthetic ability as another possible mechanism of PBS. In their speculation, some dysfunctions of muscle spindles in the jaw closers muscles would be responsible for the impairment of an individuals’ ability in mandibular position discrimination. They did not invalidate Marbach’s theory of diagnosable psychiatric disorders but rather agreed with Green and Gelb[19], stating that although patients’ symptom and behaviors have certain psychological impact, the main underlying cause would be the unknown alterations in proprioceptive input transmission. Contrary to their expectation, the next two experimental studies comparing sensory perceptive and interdental thickness discriminative capacities in PBS and the control group both revealed insignificant results[29,34]. Nevertheless, the possibility that the sensory test was not sensitive and accurate enough to tell the threshold differences could not be excluded.

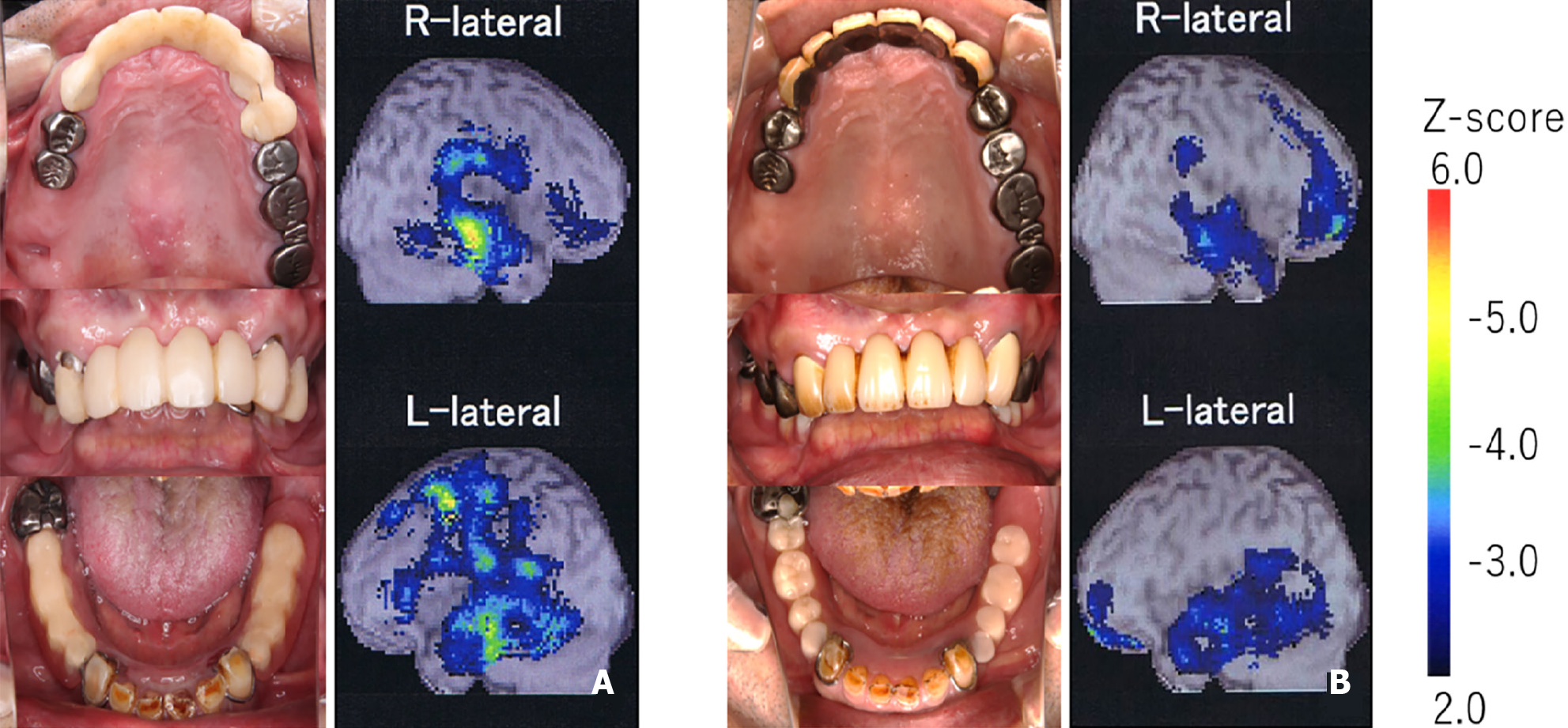

Given this unsettled controversy, “brain imaging techniques…can be utilized to evaluate whether cortical map representations in fact correspond to patient’s subjective occlusal complaints…”, Hara et al[9] suggested in their review. In 2013, Umezaki et al[16] conducted a single-photon emission computed tomography in a PBS patient, revealing asymmetrical cerebral blood flow (CBF) patterns in the frontal lobe region. Interestingly, 1 year after taking psychopharmacology, not only had the patient’s symptoms remarkably improved, but the asymmetry patterns also attenuated. This finding reinforced the “altered central processing” theory, suggesting the involvement of central nervous system dysfunction in PBS manifestation. However, in a later case-control study conducted by the same research group, regional CBF (rCBF) in 44 PBS patients and 12 control subjects had insignificant differences. The author admitted that the initial idea of comparing one whole group of PBS with normal controls was “inappropriate” and interpreted this negative results as a reflection of the heterogeneous nature in PBS. A secondary analysis of these data later revealed different rCBF patterns are in accordance with certain clinical patterns, such as laterality of the symptoms or behavior of blaming dentists. In particular, PBS patients with right-side symptoms have significant right-side predominant parietal asymmetry and left-side predominant thalamus asymmetry[28]. Disturbance in the parietal area, which includes the secondary sensory cortex, and thalamus that relay information between different subcortical areas and the cerebral cortex, might imply the complexity of PBS symptoms. In the study, the tendency of frontal lobe asymmetry is also reported as the same with experimentally reproduced occlusal discomfort.

Generally speaking, all of these above interpretations were substantially built upon personal judgment and limited clinical observations. So far, none of these proposed theories fully explain all the available cases. For example, there are PBS cases (where patients had neither psychiatric disorder nor abnormal psychological condition) that cannot be explained using the theory of psychopathological influences alone[8,10]. Besides, there are also PBS patients whose symptoms spontaneously developed, meaning there are no dental treatments related inputs to trigger peripheral alterations. As long as this controversy remains unsolved, neither specific diagnostic testing nor effective treatment can be sufficiently developed.

Based on these perspectives of etiology and pathogenesis, various authors proposed different strategies. However, they all agree that treatment should primarily focus on patients’ education and therapies that improve overall function and well-being[9,23,27,35]. In this review, apart from those treatments, we want to discuss further other underestimated perspectives; including professional education, psychopharmacotherapy, successful guidance and reliable therapeutic relation.

First and foremost, dental treatment would not be helpful and should be avoided. As many authors stated, PBS patients are considered to be “refractory to any dental treatment”[2,6,9,11,14,18,22]. However, they will always look for help from dentists, whom they believed to be the only people with enough expertise to understand their complaints and then be able to provide a “full bite correction”. In fact, on oral examination, some occlusal discrepancies may be detected, but they were far from the root cause of patients’ suffering[5,22]. Besides, a normally good occlusion can always be enhanced to become an ideal one with dentists’ intervention[23]. Such conventional treatment might initially relieve symptoms, but sooner or later, the condition only becomes worst since the patients’ occlusion was more and more distorted from the original. Hence, to prevent inappropriate, time-consuming, irreversible, extensive treatments; enhancing dental professionals’ awareness of this phenomenon is critical. Clinicians should be aware that there is no strong evidence to support that theoretically ideal occlusion must be fulfilled for a successful outcome of prosthodontic treatment[36].

Interestingly, we observed that the majority of PBS original research, including retrospective and case-control studies, came from either Japanese or German research teams[8,10,16,21,29,34,37]. This suggests that there are licensed specialists who treat the syndrome at specialized clinics in these two countries. In particular, thanks to the inclusion of PBS and other phenomena of oral psychosomatic disorders in the undergraduate dental curriculum of some Japanese universities since the early 2000s, a general dentist will be able to notice an early case of PBS and refer them to relevant treatment centers.

In terms of pharmacotherapeutics, although it has never been considered the primary choice of treatment in PBS management, medications appear to be the most applied treatment among clinical studies[8,10,13,18,38-40]. As presented in Table 3, the most frequently prescribed medications are antidepressants and antipsychotics. Originally, Marbach[2] prescribed pimozide and haloperidol, and Wong and Tsang[12] prescribe dothiepin, an antidepressant, since they regard their PBS patient as psychiatric disorder. As the etiological discussion matured, considerations for psychopharmacological mechanisms have been deepened. Other authors also applied psychotropic drugs and suggested such effects were related to biochemical alteration in central nervous system (especially the dopaminergic system)[8,16]. Besides, Clark et al[23] recommended clonazepam, an anticonvulsant, mainly for mood stabilizing, anxiety control and patients’ distraction. Since results were limited to single case reports, case series and a retrospective analysis study, prospective follow-up or clinical control study will be needed for further verification. At the same time, elucidation of psychotherapeutic mechanism for PBS should be required to be applied at scale.

| Classification | Drug’s name | Period of follow-up | Side effects | Treatment outcome | Mechanism | Level of evidences | Ref. |

| D2 blocker | PimozideHaloperidol | No report | No report | No report | Prescribed as a treatment for monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis | Expert’s opinion | Marbach[2], 1978 |

| D2 partial agonist | Aripiprazole | Average 59 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness, constipation, weight gain, nausea, diarrhea, staggering, dizziness, malaise, irritation, headache | 37% improved; 40.7% no change, 22.3% discontinued | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 27 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 |

| Anticonvulsant | Clonazepam | No report | No report | No report | Reduce anxiety and increase tolerance to the symptom | Expert’s opinion | Clark et al[23], 2005 |

| Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) | Dothiepin | Unspecified | Unspecified | Generally recovered | Prescribed as a treatment for somatic symptom disorder | Single case report | Wong and Tsang[12], 1991 |

| Amitriptyline | 390 d | No | Significant improvement | Unspecified | Single case report | Umezaki et al[16], 2013 | |

| Average 75 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness, constipation, weight gain, nausea, dry mouth, malaise | 44.8% improved; 41.3% no change, 13.9% discontinued | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 29 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 | ||

| Paroxetine | No report | Drowsiness | 1/3 improved; 2/3 no change | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 3 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 | |

| Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | Average 152 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness, constipation, nausea, dysuria, pollakiuria, staggering, dizziness, malaise | 4/7 improved; 3/7 no change | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 7 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 | |

| Duloxetine | Average 28 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness, constipation, nausea, decreased appetite | 3/7 improved; 4/7 no change | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 7 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 | |

| 5 mo | No report | Symptom improved | No report | Single case report | Bhatia et al[39], 2013 | ||

| Escitalopram | Average 18 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness, staggering, dizziness, malaise | 3/4 improved; 1/4 discontinued | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 4 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Sertraline | Average 79 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness, constipation, nausea, edema, dry mouth, decreased appetite | 7/9 improved; 2/9 no change | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 7 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 |

| Fluvoxamine | Average 24 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness | 2/4 improved; 2/4 no change | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 4 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 | |

| Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant | Mirtazapine | Average 59 d from initial administration to clinical improved day | Drowsiness, constipation, weight gain, nausea, staggering | 42.9% improved; 47.6% no change, 9.5% discontinued | Unspecified | Retrospective study, n = 21 | Watanabe et al[8], 2015 |

| Combination of TCA and D2 partial agonist | Amitriptyline; Aripiprazole | 41 mo | Staggering | Remarkable improve | Altered biochemical abnormalities related to neurotransmitter and higher brain connectivity dysfunction, especially dopaminergic system | Single case report | Umezaki et al[16], 2013 |

| Combination of TCA, benzodiazepine and D2 blocker | Amitriptyline; Lorazepam; Sulpiride | Average 99.8 d for hospitalization and 3.8 yr from discharge | Weight gain, Liver dysfunction, hyperprolactinaemia | 15/16 improved | Altered biochemical abnormalities related to neurotransmitter | Retrospective study of inpatients, n = 16 | Toyofuku[32], 2000 |

| Combination of D2 blocker and benzodiazepine | Sulpiride; Flunitrazepam | 10 mo | No report | Symptom improved | Unspecified | Single case report | Nakamura[40], 1996 |

The assessment of psychological components and the use of appropriate consultants if needed have been recommended[6,9,18,21]. Because dental professionals are not trained to practice psychological evaluation (either distraction or cognitive behavioral therapy), they are advised to refer patients to psychiatric care. However, based on our clinical observation and literature review, this is not always a practical choice. Among 12 cases of PBS in a series collected by Kelleher[11], none was successfully referred to psychiatrists for psychological assessment. Responses included “immediate rejec

In addition, the most common barrier preventing a clinician to apply psychopharmacotherapy is persuading patients to accept treatment. According to Watanabe et al[8], PBS patients had remarkably high ratios of refusal of pharmacological treatment, especially in those with dental triggers. PBS patients have such a strong belief that only dental treatment can relieve the symptom, resulting in them refusing any therapy other than dental interventions. Such belief like obsession or dominant idea grows stronger via repeated dental interventions and temporary relief. In order to shift that insufficient belief and to stop never-ending dental interventions, there needs a positive patient-doctor relationship built upon trust, empathy and efficient communication[22]. In our clinical observation, such evidence of neuromodulators helping to balance rCBF asymmetry patterns in successfully treated PBS cases would aid in patients’ understanding of medication necessity (Figure 4)[16].

Treatment for PBS is indeed difficult in the dental setting but not impossible as reported[27]. Prudent patient education with an etiological explanation based on neuroscience including brain images would help PBS patients to understand their situation and to be convinced for pharmacotherapy instead of repeated dental procedures. Moreover, even in cases of acceptance, side-effects and slow drug response would affect patient’s tendency to withdraw quickly. It seems to be more related to resistance to taking medication than to actual adverse effects. Careful contact with patients and delicate dosing are important during the follow-up period[8].

PBS is a tremendously difficult and unusual dental phenomenon that is underreported and deserves more attention. Recent studies have revealed unexplained diversity patterns among PBS’s clinical manifestation and functional brain imaging that likely represent the available sub-phenotypes of this syndrome. Further research must be focused on elucidating pathophysiological mechanisms to pave the way for efficient treatment strategy.

| 1. | Marbach JJ. Phantom bite. Am J Orthod. 1976;70:190-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Marbach JJ. Phantom bite syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135:476-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Posselt U. Physiology of occlusion and rehabilitation. 1st ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1962: 173-175. |

| 4. | Clark GT, Tsukiyama Y, Baba K, Simmons M. The validity and utility of disease detection methods and of occlusal therapy for temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Clark G, Simmons M. Occlusal dysesthesia and temporomandibular disorders: is there a link? Alpha Omegan. 2003;96:33-39. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ligas BB, Galang MT, BeGole EA, Evans CA, Klasser GD, Greene CS. Phantom bite: a survey of US orthodontists. Orthodontics (Chic.). 2011;12:38-47. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gerstner GE, Clark GT, Goulet JP. Validity of a brief questionnaire in screening asymptomatic subjects from subjects with tension-type headaches or temporomandibular disorders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:235-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Watanabe M, Umezaki Y, Suzuki S, Miura A, Shinohara Y, Yoshikawa T, Sakuma T, Shitano C, Katagiri A, Sato Y, Takenoshita M, Toyofuku A. Psychiatric comorbidities and psychopharmacological outcomes of phantom bite syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78:255-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hara ES, Matsuka Y, Minakuchi H, Clark GT, Kuboki T. Occlusal dysesthesia: a qualitative systematic review of the epidemiology, aetiology and management. J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:630-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oguchi H, Yamauchi Y, Karube Y, Suzuki N, Tamaki K. Occlusal Dysesthesia: A Clinical Report on the Psychosomatic Management of a Japanese Patient Cohort. Int J Prosthodont. 2017;30:142-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kelleher MG, Rasaratnam L, Djemal S. The Paradoxes of Phantom Bite Syndrome or Occlusal Dysaesthesia (‘Dysesthesia’). Dent Update. 2017;44:8-12, 15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wong MTH, Tsang CCA. Phantom bite in a Chinese lady. J Hong Kong Med Assoc. 1991;43:105-107. |

| 13. | Jagger RG, Korszun A. Phantom bite revisited. Br Dent J. 2004;197:241-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Leon-Salazar V, Morrow L, Schiffman EL. Pain and persistent occlusal awareness: what should dentists do? J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:989-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tinastepe N, Kucuk BB, Oral K. Phantom bite: a case report and literature review. Cranio. 2015;33:228-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Umezaki Y, Watanabe M, Takenoshita M, Yoshikawa T, Sakuma T, Sako E, Katagiri A, Sato Y, Toyofuku A. A case of phantom bite syndrome ameliorated with the attenuation of the asymmetrical pattern of regional cerebral blood flow. Jpn J Psychosom Dent. 2013;28:30-34. |

| 17. | Marbach JJ. Psychosocial factors for failure to adapt to dental prostheses. Dent Clin North Am. 1985;29:215-233. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Marbach JJ, Varoscak JR, Blank RT, Lund P. "Phantom bite": classification and treatment. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;49:556-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Greene PA, Gelb M. Proprioception dysfunction vs. phantom bite: diagnostic considerations reported. TM Diary. 1994;2:16-17. |

| 20. | Yaka T, Yatabe M, Fueki K, Enosawa S, Ai M. Psychosomatic Aspects of TMD Patients with Occlusal Disharmony -Their Association with Occlusal Condition and Mandibular Function-. J Jpn Prosthodont Soc. 1997;41:663-669. |

| 21. | Melis M, Zawawi KH. Occlusal dysesthesia: a topical narrative review. J Oral Rehabil. 2015;42:779-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Imhoff B, Ahlers MO, Hugger A, Lange M, Schmitter M, Ottl P, Wolowski A, Türp JC. Occlusal dysesthesia-A clinical guideline. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47:651-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Clark GT, Minakuchi H, Lotaif AC. Orofacial pain and sensory disorders in the elderly. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:343-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yatabe M, Yaka T, Ai M, Enosawa S, Fueki K, Yugami K, Yoshino T, Woraman G. Psychosomatic Aspects of TMD Patients with Occlusal Disharmony -Somatic and Psychogenic Symptoms and their Previous History-. Jpn J Psychosom Dent. 1996;11:135-142. |

| 25. | Yatabe M, Ai M. Clinical consideration of psychosomatic patients with mandibular dysfunction First report: Area of pain and occlusal condition. Jpn J Psychosom Dent. 1989;4:17-23. |

| 26. | Reeves JL 2nd, Merrill RL. Diagnostic and treatment challenges in occlusal dysesthesia. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:198-207. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Tamaki K, Ishigaki S, Ogawa T, Oguchi H, Kato T, Suganuma T, Shimada A, Sadamori S, Tsukiyama Y, Nishikawa Y, Masumi S, Yamaguchi T, Aita H, Ono T, Kondo H, Tsukasaki H, Fueki K, Fujisawa M, Matsuka Y, Baba K, Koyano K. Japan Prosthodontic Society position paper on "occlusal discomfort syndrome". J Prosthodont Res. 2016;60:156-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Umezaki Y, Watanabe M, Shinohara Y, Sugawara S, Kawasaki K, Tu TTH, Watanabe T, Suga T, Miura A, Takenoshita M, Sato Y, Minami I, Oyama J, Toriihara A, Yoshikawa T, Naito T, Motomura H, Toyofuku A. Comparison of Cerebral Blood Flow Patterns in Patients with Phantom Bite Syndrome with Their Corresponding Clinical Features. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:2277-2284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tsukiyama Y, Yamada A, Kuwatsuru R, Koyano K. Bio-psycho-social assessment of occlusal dysaesthesia patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:623-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Marbach JJ. Orofacial phantom pain: theory and phenomenology. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:221-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Melzack R. Pain: past, present and future. Can J Exp Psychol. 1993;47:615-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Toyofuku A. A clinical study on psychosomatic approaches in the treatment of serious oral psychosomatic disorders during hospitalization - Evaluation of "behavior restriction therapy" for oral psychosomatic disorders and consideration of its pathophysiology. Jpn J Psychosom Dent. 2000;15:41-71. |

| 33. | Mikocka-Walus A, Ford AC, Drossman DA. Antidepressants in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:184-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Baba K, Aridome K, Haketa T, Kino K, Ohyama T. [Sensory perceptive and discriminative abilities of patients with occlusal dysesthesia]. Nihon Hotetsu Shika Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;49:599-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yatabe M, Ai M, Mizutani H, Enosawa S, Yaka T. Feedback effects of masticatory muscles with submaxmal clenching differences between the temporal and the masseter muscles in normal subjects. Jpn J Psychosom Dent. 1992;7:141-148. |

| 36. | Carlsson GE. Some dogmas related to prosthodontics, temporomandibular disorders and occlusion. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68:313-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Imhoff B, Hugger A, Schmitter M, Bermejo J. Risk factors influencing treatment success in TMD patients. J Craniomand Func. 2017;9:303-312. |

| 38. | Shetti S, Chougule K. Phantom bite ‐ a case report of a rare entity. J Dent Allied Sci. 2012;1:82-84. |

| 39. | Bhatia N, Bhatia M, Singh H. Occlusal dysesthesia respond to Duloxetine. Delhi Psychiatr J. 2013;16:453-464. |

| 40. | Nakamura H. A case of “Denture-Associated Unidentified Clinical Syndrome” who Under went Dental Treatment as a Psychiatric Inpatient. Jpn J Psychosom Dent. 1996;11:177-181. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Avtaar Singh SS S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo X