©2012 Baishideng.

World J Psychiatr. Dec 22, 2012; 2(6): 102-113

Published online Dec 22, 2012. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v2.i6.102

Published online Dec 22, 2012. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v2.i6.102

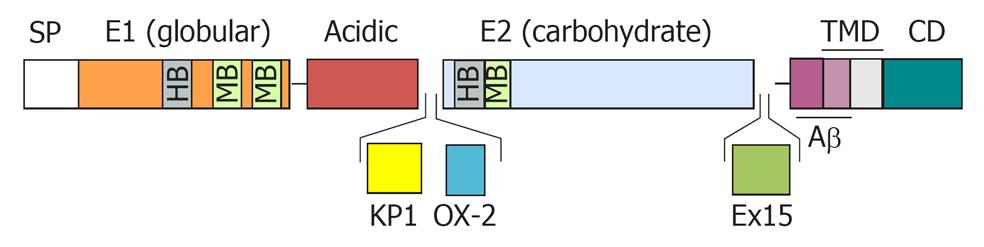

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of the amyloid precursor protein.

The diagram represents the structural domain arrangement of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene products. All domains are expressed in the APP770 isoform. The OX-2 domain is missing in APP751, whereas both the Kunitz protease inhibitor domain (KPI) and the OX-2 domain are missing in APP695. SP: Signal peptide; E1: Ectodomain 1; E2: Ectodomain 2; TMD: Transmembrane domain; CD: Cytosolic domain; OX-2: Domain with homology to OX-2 leukocyte antigen; Ex 15: Exon 15 product; HB: Heparin-binding domain; MB: Metal ion-binding domain.

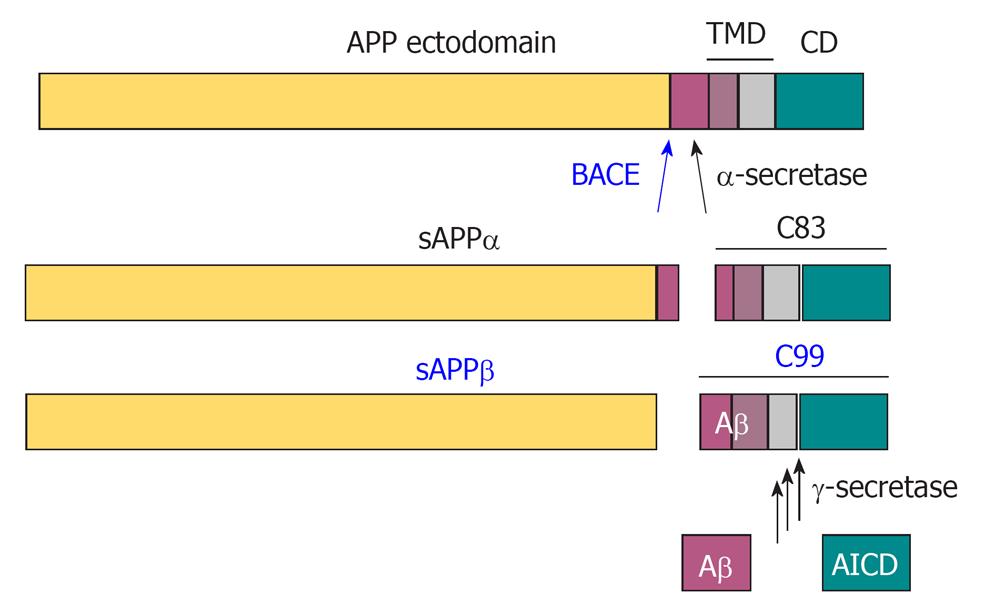

Figure 2 Proteolytic processing of amyloid precursor protein by the secretases.

In a non-amyloidogenic pathway, α-secretase cleaves amyloid precursor protein (APP) within the Aβ domain to release the α-cleaved soluble N-terminal fragment, sAPPα. β-Amyloid precursor cleaving enzyme (BACE) cleaves APP at the N-terminus of Aβ to release the β-cleaved soluble N-terminal fragment sAPPβ, and thereby initiates the amyloidogenic pathway. The remaining 99 amino acid-long C-terminal fragment (C99) is further processed at multiple sites by γ-secretase to release the APP intracellular domain (AICD) in the cytosol and Aβ peptides in the extracellular space.

- Citation: Evin G, Li QX. Platelets and Alzheimer’s disease: Potential of APP as a biomarker. World J Psychiatr 2012; 2(6): 102-113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v2/i6/102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v2.i6.102