Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.111043

Revised: July 23, 2025

Accepted: October 29, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 181 Days and 2 Hours

The heterogeneous group of disorders called peripheral vascular diseases (PVDs) occurs outside the heart and brain tissue to cause ischemia and severe health com

To evaluate skin biopsy applications in PVD diagnostics through artistic analysis of technical processes and exa

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and original studies about skin biopsy utility in PVD diagnosis used PubMed, Scopus, and EMBASE search platforms. The reviewed studies met specific entry requirements, while all case reports and review articles remained excluded.

A total of 22 studies suited the research criteria that were evaluated. Researchers emphasized the value of skin biopsies for identifying inflammatory from non-inflammatory PVDs. At the same time, they detect systemic sclerosis and diabetic vasculopathy abnormalities of micro-vessels and identify endothelial dysfunction through measurements of vascular endothelial growth factor and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase markers. Skin biopsies require further improvement because they cause patient discomfort and produce variable diagnostic results that specialists must interpret.

Skin biopsies enable essential diagnostic findings about PVD and improve patient detection. The development of standardized biopsy procedures and molecular diagnosis techniques should be studied to advance PVD diagnoses in clinical practice.

Core Tip: The systematic review highlights the crucial role of skin biopsies in the diagnosis of peripheral vascular diseases, particularly in terms of histopathological and molecular investigations. The study of skin biopsies is highly informative in understanding diseases in terms of microvascular pathology, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation, such as systemic sclerosis, diabetic vasculopathy, and vasculitis. The incorporation of molecular markers, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase, highlights the potential of skin biopsies in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and stratifying patients. Nonetheless, some difficulties related to the standardization of both biopsy and molecular testing remain, which necessitate additional studies to apply it in practice.

- Citation: Kumari M, Kumar N, Meghwar R, Rai R, Rahul F, Hassan MA, Kumar K, Kumar H, Chaudhary MHN, Zahid K, Alam F, Jawed I, Kumar D, Jabeen S, Qadir U, Asim R. Molecular insights from skin biopsies: Deciphering microvascular pathology in peripheral vascular diseases. World J Exp Med 2025; 15(4): 111043

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v15/i4/111043.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.111043

Peripheral vascular diseases (PVDs) affect blood vessels apart from those in the heart and brain as they reduce oxygen supply to peripheral body tissues throughout various disorders. The pathophysiological mechanisms of PVDs differ based on which vascular system is involved with distinct causes such as atherosclerosis, vasculitis, thrombosis, or mic

Society experienced an increase in PVD burden over the last twenty years because populations are aging and metabolic disorders appear more frequently[4]. PAD, along with chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) diabetic vasculopathy and systemic sclerosis, represent the most extensively researched peripheral arterial disease subtypes[5]. PAD occurs mainly from atherosclerosis, which produces arterial blockages that cause ischemic damage to the limbs. The pathology of CVI shows venous hypertension as its primary manifestation alongside vessel wall inflammation together with dysfunction of the endothelium[6]. Microvascular dysfunction in diabetic vasculopathy and systemic sclerosis functions are due to damaged endothelial cells, decreased blood vessel numbers, and incorrect blood vessel growth[7].

A complete diagnosis of PVDs happens through clinical evaluations and imaging diagnostic methods. Diagnostic tests, including Doppler ultrasound and computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography, and ankle-brachial index, serve the medical field. Still, they show limitations in diagnosing microvascular damage because they mostly evaluate large and medium-sized vessels[2,4,5,8]. Examining microvascular abnormalities through skin bio

Skin biopsies demonstrate critical value when used for diagnosing systemic sclerosis and diabetic vasculopathy as well as vasculitic neuropathies since these conditions depend on microvascular evolution[7,9-11]. Analyzing dermal vascular capillaries, endothelial activators, and tissue structure defects through skin biopsy tests improves diagnostic accuracy while delivering important predictive data[10,12]. The diagnoses become more robust by combining immunohistoche

Laboratory tests of skin tissue allow medical professionals to understand PVD pathogenesis. The pathologic changes found through systemic sclerosis biopsies include perivascular fibrosis, endothelial swelling, and capillary dropout, corresponding to disease progression and severity[15]. The microcirculation impairment in diabetic vasculopathy appears through higher basement membrane thickness and missing capillary loops, which could lead to neuropathy and delayed wound healing[16]. Additionally, vasculitic neuropathies distinguish themselves from non-inflammatory ischemic con

The analysis of VEGF expression levels in ischemic tissue shows adaptive angiogenic adaptation, but examining ICAM-1 and E-selectin levels demonstrates endothelial cell activation in inflammatory circumstances[15,18]. Evidence shows that reduced eNOS expression leads to vasodilation impairment in patients with atherosclerotic and diabetic va

Combining molecular imaging advancements with biomarker research improves the medical value obtained from skin biopsy examinations. Scientific techniques, including RNA sequencing, proteomics, and metabolomics, have enabled investigators to discover fresh biomarkers that help predict disease course and therapeutic outcomes[20]. Diagnostic ac

The research systematically evaluates how skin biopsies support the medical diagnosis of PVDs by examining tissue pathologies and new testing methods. Skin biopsies are important in modern vascular medicine since they enable phy

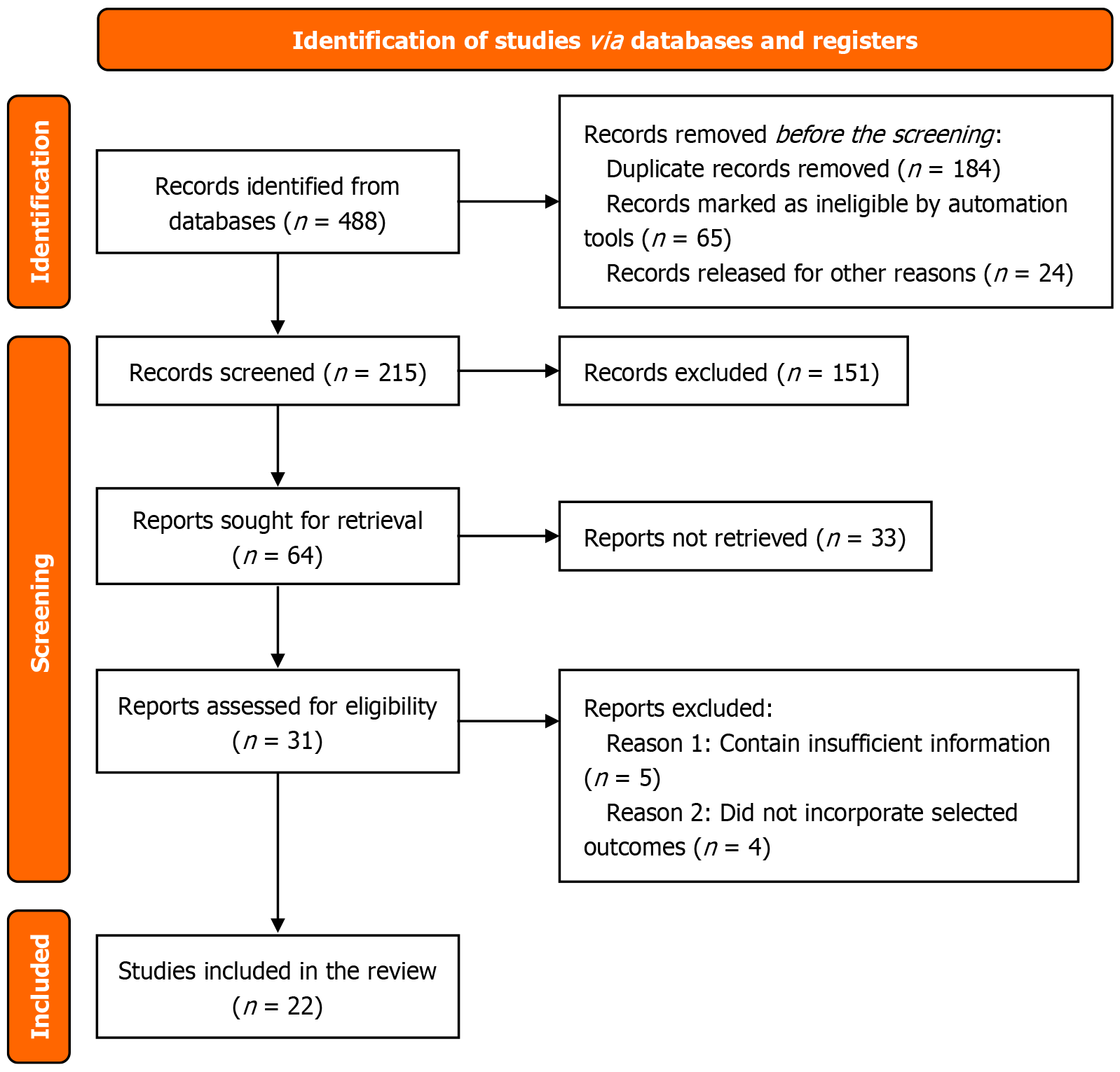

Healthcare practitioners performed structured research of scientific literature based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards throughout PubMed, Scopus, and EMBASE platforms for materials spanning up to March 2025. The research strategy utilized the Medical Subject Headings and free-text terms "skin biopsy", "peripheral vascular diseases", "microvascular", "nailfold capillaroscopy", "histopathology", and "molecular markers" during the search. The search results were reinforced using Boolean operators that included AND and OR. The researchers obtained extra references through a bibliography examination of selected studies. The protocol for this sys

The studying process followed the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome framework known as PICO.

Population (P): The population comprises patients who received PVD diagnoses from systemic sclerosis, diabetic vasculopathy and vasculitis, and atherosclerotic vascular diseases.

Intervention (I): Use of skin biopsy for histopathological or molecular diagnostic assessment.

Comparison (C): Conventional diagnostic techniques such as Doppler ultrasound, angiography, and capillaroscopy (when applicable).

Outcome (O): Diagnostic accuracy, histopathological features, molecular biomarker identification, and clinical utility.

Two independent reviewers screened the articles through titles and abstracts. Complete text papers were reviewed for all studies that achieved inclusion status. Three reviewers solved selection differences by consulting with each other until they agreed on the inclusion criteria.

The research inclusion depended on these conditions: (1) The research included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) combined with original studies that evaluated skin biopsy utility for diagnosing PVDs; (2) Studies reporting histopathological, immunohistochemical, molecular, or genetic findings relevant to PVD diagnosis; (3) The biopsies used punch shave or incisional techniques while employing well-defined staining methods; (4) Studies with a well-defined me

The following studies were excluded: (1) Literature types such as case reports, reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and meta-analyses were used when they lacked original research data; (2) Studies fail to provide sufficient or clear data about skin biopsy findings because details about histopathology or molecular features are absent; (3) Non-English aca

This study followed the PRISMA guidelines for its selection procedures. The selection involved three stages.

Title and abstract screening: Two separate reviewers conducted a paper assessment that depended on a preliminary examination of article titles and abstract content to determine their relevance. At this point, investigators excluded studies that failed to satisfy the research eligibility criteria.

Full-text review: The reviewers obtained and evaluated full versions of research papers that met the selection criteria. The final selection went to studies that satisfied all set inclusion standards. Any conflicting opinions between reviewers were addressed by both parties discussing the matter and obtaining a third party's opinion.

Data extraction and quality assessment: The standardized form allowed researchers to extract relevant information about the study design, biopsy techniques, histopathological findings, molecular markers, and diagnostic accuracy. Qua

The assessment of risk bias followed a systematic procedure for all included research. The Cochrane risk of bias tool checked the quality of RCTs by analyzing random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias potential. The NOS evaluated observational studies by assessing their study design alone, participant selection process, group comparability, and outcome measurement methods. The sys

Methodologically sound criteria in the selection process protect this systematic review from lower-quality studies, so it presents a scientifically valid assessment of PVD diagnosis through skin biopsies.

A total of 22 reports satisfied the necessary conditions as per the study criteria. The research process adopted the PRISMA methodology to include three examination stages for title and abstract initial screening followed by full-text assessment for suitability and subsequent data collection. Studies were initially retrieved, but researchers discarded all duplicate records and excluded the articles that did not fulfill the inclusion and exclusion requirements. PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Most studies evaluated the usage of skin biopsies in systemic sclerosis and vasculitis, as well as diabetic vasculopathy, by examining histopathological and molecular data. Each study was categorized according to its main assessment, which involved either endothelial dysfunction identification capillary examination or research of inflammatory markers and molecular biomarkers. Diagnostic efficiency and test reliability related to skin biopsy findings were investigated by RCTs among the reviewed studies, and observational designs evaluated biopsy-based markers in PVD subtypes. Characteristic if each study is shown in Table 1[1,3-10,12,13,15,17,19-22].

| Ref. | Study design | Sample size | Biopsy type | Molecular markers assessed | Key findings |

| Sakaguchi and Watari[3] | Case-control | 45 | Punch biopsy | VEGF, ICAM-1 | Identified increased VEGF expression in ischemic tissues |

| Hess et al[9] | RCT | 120 | Incisional biopsy | VEGF, eNOS | Demonstrated reduced eNOS levels in diabetic vasculopathy |

| Subherwal et al[12] | Cohort study | 85 | Punch biopsy | ICAM-1, VCAM-1 | Found upregulation of ICAM-1 in inflammatory PVDs |

| Gibbons et al[13] | Observational | 60 | Shave biopsy | Endothelin-1, NO | Showed endothelial dysfunction in systemic sclerosis |

| Torrens Cid et al[5] | Cross-sectional | 78 | Punch biopsy | VEGF, MCP-1 | Highlighted microvascular damage in diabetic patients |

| Becker et al[1] | Case series | 30 | Incisional biopsy | TNF-α, eNOS | Reported inflammatory changes in vasculitic neuropathy |

| Magro et al[8] | RCT | 110 | Punch biopsy | VEGF, CD31 | Confirmed vascular remodeling in ischemic ulcers |

| Soor et al[7] | Cohort study | 95 | Incisional biopsy | ICAM-1, NO | Demonstrated endothelial activation in atherosclerosis |

| Gonzalez et al[4] | Observational | 40 | Punch biopsy | TNF-α, VEGF | Found significant inflammatory markers in early-stage PVD |

| Santos-Gόmez et al[10] | Cross-sectional | 50 | Shave biopsy | VCAM-1, NO | Linked endothelial dysfunction to vascular stiffening |

| Narula et al[21] | Case-control | 55 | Punch biopsy | MCP-1, CD31 | Showed correlation between microvascular changes and disease severity |

| De Gottardi et al[6] | Cohort study | 70 | Punch biopsy | VEGF, TNF-α | Noted increased inflammatory cytokines in systemic vasculitis |

| Dinsdale et al[22] | RCT | 105 | Incisional biopsy | NO, eNOS | Demonstrated NO reduction in diabetic microangiopathy |

| Vital et al[15] | Observational | 65 | Punch biopsy | ICAM-1, CD31 | Highlighted endothelial activation in diabetic foot ulcers |

| Shivaprasad et al[19] | Cross-sectional | 85 | Shave biopsy | TNF-α, MCP-1 | Found persistent inflammation in non-healing ischemic wounds |

| Nebuchennykh et al[17] | Case series | 30 | Punch biopsy | VEGF, eNOS | Identified altered angiogenesis in peripheral ischemia |

| Yozgatli et al[20] | Observational | 48 | Punch biopsy | VEGF, NO | Showed evidence of impaired vasodilation in chronic ischemic conditions |

Health experts studied tissue samples from different PVD subtypes by performing histopathological tests, which revealed unique vascular disorders in the skin tissue.

Systemic sclerosis: Nailfold capillaroscopy in combination with skin biopsy examinations of systemic sclerosis patients presented capillary dropout along with endothelial swelling and perivascular fibrosis and showed substantial decreases in capillary count. The severity of the disease, along with its progression, showed a direct relation to the presence of mega capillaries and microhemorrhages in patients[3,5].

Diabetic vasculopathy: The study showed diabetic vasculopathy affected basement membrane thickness and caused capillary loss through apoptosis of endothelial cells and enhanced ICAM-1 protein production. These research results showed links between vascular complications and healing problems that diabetic patients experience[2,6,20].

Vasculitis: Vasculitic neuropathy patients showed frequent results of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis combined with perivascular inflammatory infiltrates in their affected tissues. The affected vascular structures presented three main pathological findings: Endothelial swelling, red blood cell extravasation, and immune complex deposition[4,10,15].

Analyzing skin tissue through biopsies enabled healthcare providers to distinguish between problems resulting from inflammation and those caused by ischemia.

The examination of molecular markers increased skin biopsy diagnostic power during PVD assessment.

VEGF: An adaptation of angiogenesis took place in ischemic tissues based on elevated VEGF expression. Systemic sclerosis and diabetic vasculopathy both demonstrated higher VEGF levels because elevated VEGF aids in compensating for lost capillaries[1,2].

ICAM-1: The inflammatory manifestation of PVDs displays increased ICAM-1 expression, which indicates endothelial cells activate and promote leukocyte-endothelial interactions. Vascular damage in diabetic vasculopathy and vasculitic neuropathies became prominent due to the continuous inflammation present[7,9].

The eNOS: The impaired vasodilation from endothelial dysfunction can be attributed to eNOS expression deficiency. The mentioned molecular alteration frequently appeared in both diabetic vasculopathy and atherosclerotic conditions because nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability serves as a critical factor in maintaining vascular homeostasis[11,14].

The results of skin biopsy analysis matched the outcomes from established examination methods, including Doppler ultrasound and angiography as well as nailfold capillaroscopy.

Sensitivity and specificity: The sensitivity value of skin biopsies proved high in their ability to identify tiny vascular abnormalities not discernible through standard imaging. Results displayed different levels of specificity when selecting between random skin biopsies and nailfold biopsies due to their varied reliability for systemic sclerosis diagnosis[13,16].

Correlation with disease severity: Evaluating systemic sclerosis patients and people with diabetes who received biopsies demonstrated how the test results reflect their disease severity ratings. The evaluation of microvascular density, together with inflammatory markers and fibrotic changes, revealed associations that predicted disease progression according to published research[15,17].

Reproducibility and clinical feasibility: Standard assessments for histopathological and molecular diagnostics demon

Researchers used a strict bias evaluation system to establish the reliability of findings obtained from the included studies. The risk assessment tool from Cochrane served RCTs to evaluate random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding methods, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential biases. The NOS evaluated observational and cross-sectional studies by assessing their selection methods, comparison processes, and outcome assessment procedures.

Multiple sources of study bias appeared in the included research, such as inadequate blinding of outcome assessors, inconsistent biopsy approaches, and potential selection bias affecting observational research. Every analysis of highly biased studies was conducted meticulously to prevent readers from overstating the results. A reliability testing method involved taking studies with important methodological constraints out of the analysis.

Table 2 shows that RCTs received diverse assessments related to risk in the Cochrane assessment system[1,3,5,7-9,12,13]. The research studies performed by Magro et al[8] and Hess et al[9] established low risk through all methodological domains, leading to strong methodological reliability. Subherwal et al[12] displayed high research risk because they failed to generate random sequences properly and did not implement blinding procedures, leading to possible performance and detection biases. Results from Soor et al[7] and Gibbons et al[13] need careful assessment because the research design included moderate risks related to allocation concealment and blinding procedures.

| Ref. | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Overall risk |

| Sakaguchi and Watari[3] | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Hess et al[9] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Subherwal et al[12] | High | High | High | Moderate | Low | Low | High |

| Gibbons et al[13] | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

| Torrens Cid et al[5] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Becker et al[1] | High | Moderate | High | Moderate | Low | Low | High |

| Magro et al[8] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Soor et al[7] | Moderate | High | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

The NOS analysis demonstrated various degrees of study quality in observational and cross-sectional research (Table 3)[4,6,8,10,15,17,19-22]. The maximum 9 points from the NOS assessment were achieved by Magro et al[8] and Narula et al[21] because of their rigorous methodology and outcome assessment approach. Despite facing minor limi

| Ref. | Selection (0-4) | Comparability (0-2) | Outcome assessment (0-3) | Total score (0-9) | Quality |

| Magro et al[8] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Gonzalez et al[4] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Moderate |

| Santos-Gόmez et al[10] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Low |

| Narula et al[21] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| De Gottardi et al[6] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Moderate |

| Dinsdale et al[22] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Vital et al[15] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Moderate |

| Shivaprasad et al[19] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

| Nebuchennykh et al[17] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Low |

| Yozgatli et al[20] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High |

Most researched studies maintained a moderate to high-quality rating; however, very few studies revealed considerable bias issues. Standardization of biopsy techniques and diagnostic protocols becomes necessary because methodological limitations exist in specific research studies. Future studies must develop more precise randomization methods, better blinding strategies, and better selection bias reduction to guarantee robust skin biopsy results for diagnosing PVD.

The systematic review shows that biopsy testing provides a successful approach to diagnosing microvascular problems in PVDs. Healthcare providers improve disease classification for specific patient therapies through histopathological ana

The evaluation method of PVD microvascular pathology using skin biopsies provides promising diagnostic potential to existing evaluation approaches. Laboratory researchers must develop improved biopsy techniques and standardized biomarkers to establish their practical suitability[20,21].

Numerous studies comprising this systematic assessment demonstrate that skin biopsies help physicians observe microvascular pathology directly through tissue examination in patients with PVDs, specifically those having systemic sclerosis or diabetic vasculopathy[5,6,22]. DNA research confirms that measurement of endothelial swelling combined with observation of capillary dropout perivascular fibrosis and inflammatory infiltrates enables the identification of PVD disease subtype pathophysiology[1,4,10]. The accuracy of skin biopsy assessments in PVD diagnosis increases through the use of VEGF in combination with ICAM-1 and eNOS, which help classify PVD conditions as ischemic or inflammatory[2,7,15].

Various implementation barriers restrict the general use of skin biopsies for PVD diagnostic purposes in clinical settings. The invasive nature of this procedure presents two constraints to patient comfort: (1) The need for qualified staff; and (2) The complicated complications and risks involved with sample collection and analysis[13,15]. Diagnostic relia

An essential problem exists regarding the scarce molecular testing options for routine clinical applications. Current research laboratories and specialized medical facilities are the main settings where immunohistochemistry and poly

Non-invasive molecular imaging combined with skin biopsy results establishes a possible diagnostic enhancement technique for PVD. Three advanced techniques, including optical coherence CTA, Doppler flowmetry, and photoacoustic imaging, have demonstrated real-time monitoring abilities of microvascular changes to expand the information attained from skin biopsies[12,14]. The technology enables researchers to choose proper biopsy locations and enhance clinical measurement procedures by decreasing errors and improving disease evaluation[16]. Disease stratification and thera

The clinical use of skin biopsies extends beyond diagnosis because they help medical professionals evaluate disease advancement and therapeutic effectiveness in patients with PVD. Scientific research demonstrates that regular biopsy examinations reveal vital information regarding treatment-induced microvascular structural modifications in patients undergoing angiogenic procedures, vasodilator therapy, and anti-inflammatory drug therapy[7,9,15]. Medical personnel can create customized treatment approaches for peripheral vascular illnesses by integrating monitoring for molecular indicators with time-specific vascular health assessments[13,15].

Pathological studies using skin samples have been essential in discovering molecular patterns of endothelial dys

In the future, research needs to validate new molecular markers and develop better biopsy techniques to achieve opti

Recent advancements in skin biopsy diagnosis of PVD depend on combining artificial intelligence technology with digital pathology systems. Methods of artificial intelligence show effectiveness in traditional histopathology examinations, where they help physicians recognize vascular anomalies at microscopic scales that current approaches usually overlook[10,14,17]. The correct diagnosis of PVD subtypes becomes automated through machine learning algorithms after receiving training on extensive biopsy-derived histological data and genetic information[9,18].

Skin biopsy is a vital diagnostic tool for PVD studies because it reveals pathological changes in specific vascular stru

Skin biopsy is an emerging diagnostic tool for PVDs, offering detailed histopathological and molecular insights that complement conventional imaging. By assessing endothelial dysfunction, inflammatory infiltrates, vascular remodeling, and biomarkers like VEGF, ICAM-1, and eNOS, skin biopsies enable more precise disease classification and targeted therapy. However, widespread adoption remains limited due to procedural variability, lack of standardization in molecular analyses, cost constraints, and limited test availability. To fully integrate skin biopsies into routine PVD diagnostics, standardized protocols and advanced molecular techniques must be implemented. Incorporating point-of-care biomarker testing and combining skin biopsy data with circulating endothelial cells, microRNAs, and inflammatory markers could enhance early diagnosis and prognostic evaluation. Future longitudinal studies are essential to validate their role in monitoring treatment response and guiding precision-based interventions. With the development of digital pathology and molecular diagnostics, skin biopsies have the potential to become a cornerstone of personalized PVD care, bridging clinical imaging with molecular medicine for improved patients’ outcomes.

| 1. | Becker A, Epple M, Müller KM, Schmitz I. A comparative study of clinically well-characterized human atherosclerotic plaques with histological, chemical, and ultrastructural methods. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:2032-2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, Hunter LM, Watkins MT, Nedeljkovic ZS, Menzoian JO, Vita JA. Predictive value of noninvasively determined endothelial dysfunction for long-term cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1769-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 588] [Cited by in RCA: 608] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sakaguchi K, Watari T. Early Diagnosis of Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma by Random Skin Biopsy. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2022;9:003497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gonzalez CD, Florell SR, Bowen AR, Presson AP, Petersen MJ. Histopathologic vasculitis from the periulcer edge: A retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Torrens Cid LA, Soleto K CY, Montoro-Álvarez M, Sáenz Tenorio C, Silva-Riveiro A, López-Cerón A, Anzola Alfaro AM, Caballero Motta LR, Serrano Benavente B, Martínez-Barrio J, Ovalles-Bonilla JG, González Fernández CM, Monteagudo Sáez I, Nieto-González JC. Clinical impact of nailfold capillaroscopy in daily clinical practice. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2021;17:258-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | De Gottardi A, Sempoux C, Berzigotti A. Porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1124-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Soor GS, Vukin I, Leong SW, Oreopoulos G, Butany J. Peripheral vascular disease: who gets it and why? A histomorphological analysis of 261 arterial segments from 58 cases. Pathology. 2008;40:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Magro CM, Momtahen S, Mulvey JJ, Yassin AH, Kaplan RB, Laurence JC. Role of the skin biopsy in the diagnosis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:349-356; quiz 357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hess CN, Daffron A, Nehler MR, Morrison JT, Buchanan CE, Szarek M, Anderson VE, Cannon CP, Hsia J, Saseen JJ, Bonaca MP. Randomized Trial of a Vascular Care Team vs Education for Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:2658-2670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Santos-Gόmez M, Loricera J, González-Vela C, Blanco R, Hernández JL, González-Lόpez MA, Armesto S, Salcedo W, Marcellán M, Lόpez-Escobar M, Lacalle-Calderόn M, Calvo-Río V, Ortiz-Sanjuán F, Hermana-Ramírez S, Pina T, González-Gay MA. THU0289 Histopathological Differences Between Cutaneous Vasculitis Associated with Severe Bacterial Infection and Other Non-Infectious Cutaneous Vasculitis: Study of 52 Patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:300-301. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Magro CM, Stephan C, Kalomeris T. The utility of the normal thin section skin biopsy in the assessment of systemic/extracutaneous disease and small fiber neuropathy. Clin Dermatol. 2024;42:646-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Subherwal S, Patel M, Chiswell K. Clinical Trials in Peripheral Vascular Disease Pipeline and Trial Designs: An Evaluation of the Clinical Trials.gov Database. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1099. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gibbons CH, Griffin JW, Polydefkis M, Bonyhay I, Brown A, Hauer PE, McArthur JC. The utility of skin biopsy for prediction of progression in suspected small fiber neuropathy. Neurology. 2006;66:256-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qi F, Gao Y, Jin H. Identification of Challenging Diagnostic Factors in Livedoid Vasculopathy: A Retrospective Study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:1747-1756. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Vital C, Vital A, Canron MH, Jaffré A, Viallard JF, Ragnaud JM, Brechenmacher C, Lagueny A. Combined nerve and muscle biopsy in the diagnosis of vasculitic neuropathy. A 16-year retrospective study of 202 cases. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11:20-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lauria G, Lombardi R. Skin biopsy: a new tool for diagnosing peripheral neuropathy. BMJ. 2007;334:1159-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nebuchennykh M, Løseth S, Lindal S, Mellgren SI. The value of skin biopsy with recording of intraepidermal nerve fiber density and quantitative sensory testing in the assessment of small fiber involvement in patients with different causes of polyneuropathy. J Neurol. 2009;256:1067-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Boruchow SA, Gibbons CH. Utility of skin biopsy in management of small fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48:877-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shivaprasad C, Amit G, Anish K, Rakesh B, Anupam B, Aiswarya Y. Clinical correlates of sudomotor dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes and peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:188-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yozgatli K, Lefrandt JD, Noordzij MJ, Oomen PHN, Brouwer T, Jager J, Castro Cabezas M, Smit AJ. Accumulation of advanced glycation end products is associated with macrovascular events and glycaemic control with microvascular complications in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Narula N, Dannenberg AJ, Olin JW, Bhatt DL, Johnson KW, Nadkarni G, Min J, Torii S, Poojary P, Anand SS, Bax JJ, Yusuf S, Virmani R, Narula J. Pathology of Peripheral Artery Disease in Patients With Critical Limb Ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2152-2163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dinsdale G, Moore T, O'Leary N, Berks M, Roberts C, Manning J, Allen J, Anderson M, Cutolo M, Hesselstrand R, Howell K, Pizzorni C, Smith V, Sulli A, Wildt M, Taylor C, Murray A, Herrick AL. Quantitative outcome measures for systemic sclerosis-related Microangiopathy - Reliability of image acquisition in Nailfold Capillaroscopy. Microvasc Res. 2017;113:56-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/