Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.110893

Revised: June 26, 2025

Accepted: September 19, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 184 Days and 19.5 Hours

Radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy remains a cornerstone in the management of differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC). The therapeutic efficacy of RAI depends on thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-driven uptake via the sodium-iodide sym

Core Tip: Radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy is central to differentiated thyroid cancer management, relying on thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-driven sodium-iodide symporter activity. Current protocols elevate TSH but overlook its circadian peak overnight. Aligning RAI administration with this peak via evening dosing may enhance iodine uptake, improve efficacy, reduce exposure, and optimize workflow. Preclinical evidence supports this chronotherapeutic approach, although clinical data are lacking. This review synthesizes existing evidence and proposes timed RAI administration as a novel strategy warranting prospective evaluation.

- Citation: Meristoudis G, Savvidis C, Ilias I. Chronotherapeutic optimization of radioactive iodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: The rationale for evening administration. World J Exp Med 2025; 15(4): 110893

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v15/i4/110893.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.110893

Differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC; mainly papillary thyroid cancer and follicular thyroid cancer) is the most prevalent malignancy of the endocrine system. Its management typically includes total or near-total thyroidectomy, followed by adjuvant radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy using iodine-131 (¹³¹I). The latter is a therapeutic mainstay aimed at ablating residual thyroid tissue and microscopic disease[1,2]. ¹³¹I is a β- and γ-emitting isotope with a physical half-life of approximately eight days. Its high specific radioactivity (4.6 × 1014 Bq/g) allows selective absorption by thyroid tissue via the sodium-iodide symporter (NIS), a membrane glycoprotein that actively transports iodide into thyroid follicular cells[3,4]. It is through this mechanism that RAI exhibits both diagnostic and cytotoxic properties.

The expression and functional activity of NIS are upregulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), the central hormonal driver of iodine uptake in both healthy and neoplastic thyroid cells[4,5]. In patients with DTC who receive RAI after surgery, achieving a TSH level typically exceeding 30 mU/L is vital for optimizing RAI uptake and enhancing therapeutic efficacy[5-8]. This is accomplished through either thyroid hormone withdrawal (THW) or administration of recombinant human TSH (rhTSH), with the aim of enhancing iodine avidity prior to RAI therapy.

However, while TSH elevation is the cornerstone of RAI preparation, the timing of administration relative to circadian TSH variation has not been systematically addressed in clinical practice. In this article, we synthesize physiological, preclinical, and clinical data to explore the rationale for aligning RAI dosing with endogenous TSH peaks—most notably through evening administration—as a novel chronotherapeutic strategy.

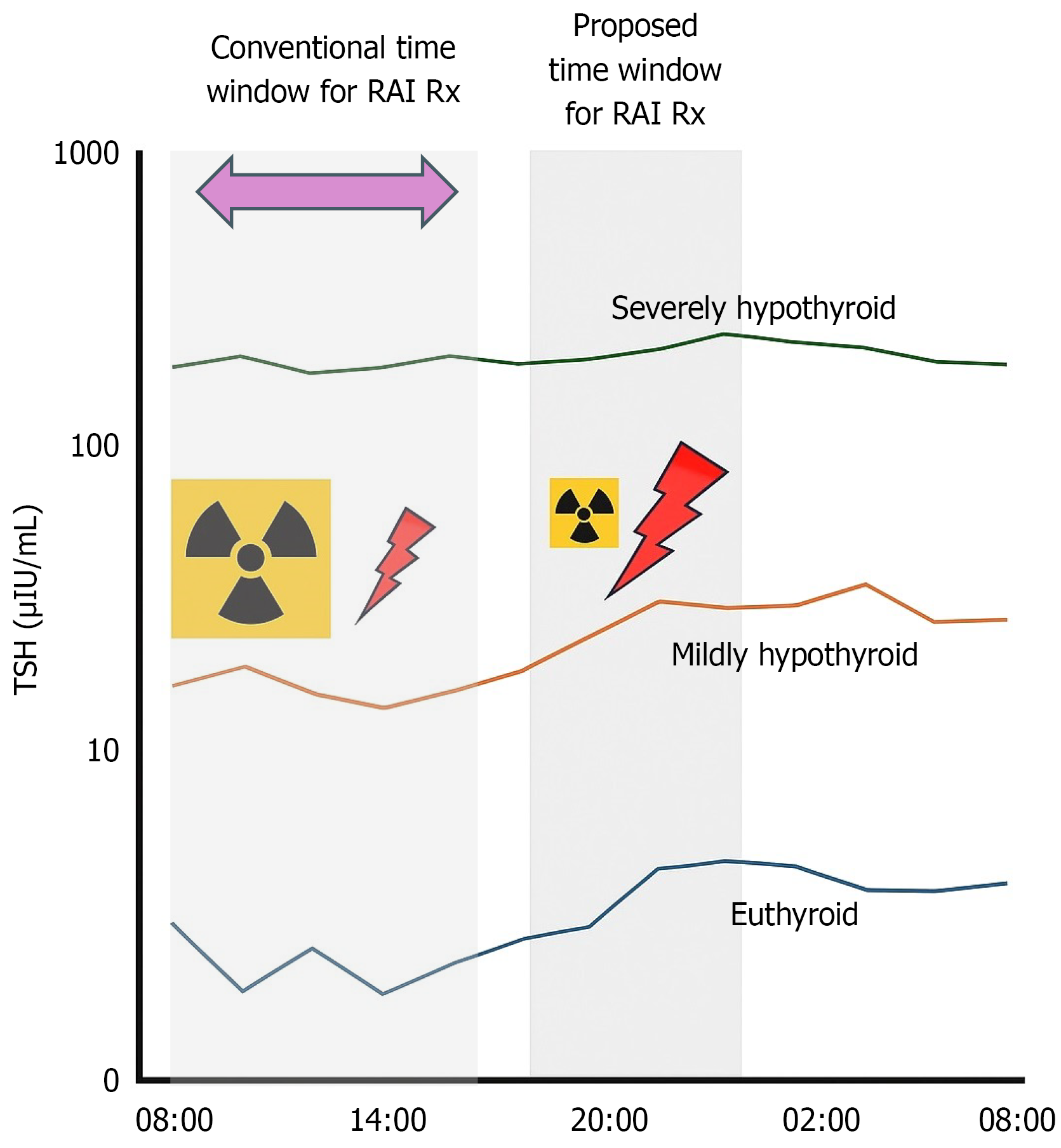

TSH secretion exhibits a circadian rhythm under hypothalamic-pituitary regulation, typically peaking between 10 PM and 2 AM and reaching a nadir in the late afternoon[9-12]. In the hypothyroid state, such as during THW, circulating TSH levels may exceed 60-80 mU/L, potentially dampening but not eliminating its diurnal variation[13-15] (Figure 1). This persistent fluctuation suggests that even in the setting of markedly elevated TSH, alignment with circadian peaks could provide additional pharmacodynamic benefit.

Preclinical data from murine models support this notion. Specifically, studies have demonstrated that administration of ¹³¹I during TSH peaks leads to enhanced thyroidal uptake and retention of the isotope, potentially attributable to increased NIS transcriptional activity and membrane localization during this time[16]. While human trials are absent, the biological rationale for enhancing RAI efficacy by aligning with TSH surges, merits further investigation.

Moreover, the pharmacokinetics of rhTSH—a common alternative to THW—may also be amenable to circadian modulation. While rhTSH induces rapid and sustained TSH elevation over 24-48 hours, the timing of injection relative to natural TSH peaks has not been optimized[17,18]. Future strategies might include synchronizing rhTSH administration with endogenous TSH rhythms to exploit synergistic effects on NIS activity.

From a physiological standpoint, administering RAI in the evening may capitalize on peak endogenous TSH levels, potentially enhancing iodine uptake in residual thyroid or metastatic foci (Figure 1). This could translate into improved ablation rates or allow for dose de-escalation without compromising efficacy, particularly in low- to intermediate-risk patients[19,20]. Furthermore, increased thyroidal iodine retention may reduce off-target radiation exposure, offering long-term safety advantages—especially in younger patients or those concerned with reproductive health[21,22].

Operationally, evening administration aligns with patient-centered care. Patients undergoing RAI must adhere to fasting protocols—commonly two hours prior to ingestion and several hours thereafter. Evening scheduling allows for normal daytime meals and fasting during sleep, potentially improving compliance and tolerability. Furthermore, nausea, a frequent side effect of RAI observed in 25% of patients[23], may be more tolerable if it occurs overnight during sleep. Logistical benefits are also notable. Staggered scheduling could alleviate bottlenecks in high-volume nuclear medicine therapy centers, enhance resource utilization, and increase accessibility for patients with daytime obligations. In fact, institutions like the University of Washington Medical Center have already implemented afternoon dosing protocols, indicating feasibility and acceptance within clinical workflows[24].

Despite these theoretical and practical benefits, several barriers to evening RAI administration remain. Chief among these is the concern for adequate post-treatment monitoring. Inpatient protocols typically include immediate post-RAI observation for complications such as nausea, vomiting, or radiation-induced discomfort. Evening dosing may necessitate overnight staffing adjustments to maintain clinical vigilance, particularly in vulnerable populations.

Additionally, coordination of follow-up imaging—such as post-therapy whole-body scans (WBS)—could be impacted. Standard practice involves imaging at 3-10 days post-RAI; shifting dosing time may require realignment of scanning protocols to maintain consistency in dosimetric interpretation and avoid misclassification of iodine distribution patterns.

Moreover, the pharmacokinetics of ¹³¹I, although dominated by its long half-life, may still be influenced by circadian physiology. Renal clearance, gastrointestinal motility, and hepatic metabolism are all under circadian control, raising theoretical concerns about variable systemic exposure based on time of dosing[3,12]. However, these effects are likely minor in the context of high TSH-driven uptake and remain unquantified in humans.

Patients with radioiodine-refractory DTC (RR-DTC) represent a distinct therapeutic challenge due to reduced or absent ¹³¹I uptake, often from impaired NIS function (primarily due to reduced or absent expression of NIS). No clinical studies have assessed the timing of RAI administration specifically in RR-DTC. The correlation between NIS expression and RAI sensitivity is not always straightforward. Some studies indicate that while BRAF mutations are associated with lower NIS expression, they may not always predict RAI sensitivity, highlighting the complexity of the disease[25]. Thus, we can speculate that circadian TSH peaks may transiently enhance NIS expression and iodine uptake, particularly in partially dedifferentiated cells. This strategy may hold promise in the setting of redifferentiation therapies (e.g., MAPK pathway inhibitors), where restored iodine avidity could be further optimized by administering RAI at times of maximal endogenous or pharmacologic TSH stimulation. Although supported by murine models and theoretical considerations, these approaches lack validation in human studies. Given the poor prognosis of RR-DTC, chronotherapy merits exploration in clinical trials, particularly in patients with partial iodine uptake or undergoing redifferentiation. Until then, evening RAI dosing in RR-DTC should be considered investigational and limited to research settings or individualized protocols.

Overall, perhaps the most significant limitation is the absence of clinical data directly comparing morning and evening RAI administration. Neither American Thyroid Association nor European Thyroid Association guidelines address timing of RAI delivery[2,26]. Current protocols prioritize biochemical TSH thresholds and adherence to low-iodine diet, but overlook the potential impact of dosing time on treatment outcomes. As a result, clinical decision-making remains shaped more by institutional convention than evidence-based optimization.

We must acknowledge the limitations of our overview, as our synthesis of the existing literature reveals several critical gaps. While multiple studies confirm the circadian rhythm of TSH and its correlation with NIS-mediated iodine uptake[5,11,15], no prospective human trials have examined the impact of RAI timing on therapeutic outcomes. Meta-analyses have focused on TSH elevation methods (e.g., THW vs rhTSH)[27], while randomized trials such as those by Mallick et al[20] have compared RAI dose levels, but not the timing of RAI administration.

There is a pressing need for prospective, controlled studies to assess the clinical impact of circadian-aligned RAI dosing. Such studies should incorporate real-time TSH monitoring, standardized dosimetry, and outcome metrics including thyroglobulin suppression, WBS clearance, recurrence rates, and reproductive safety endpoints. Stratification by TSH preparation method, risk category, and iodine avidity would allow for granular interpretation.

In addition to clinical efficacy, research should assess the feasibility of implementing evening protocols, including workflow optimization, radiation safety adherence, and patient acceptability. Outpatient low-dose RAI protocols can provide an opportunity to test evening administration strategies with minimal impact on clinical operations[28].

Chronotherapy—long recognized in fields such as oncology[29] and endocrinology— provides a new perspective for optimizing RAI therapy in DTC. Aligning RAI administration with endogenous TSH peaks, particularly via evening dosing, may enhance iodine uptake, improve ablation outcomes, and minimize systemic toxicity. Though the physiological reasoning and preclinical findings are convincing, clinical confirmation is necessary. Until such evidence emerges, consideration of evening RAI administration should be reserved for carefully selected patients and supported by robust institutional protocols. As thyroid cancer management evolves toward greater personalization, timing of RAI delivery may represent a modifiable variable with significant therapeutic implications.

| 1. | Mettler FA, Guiberteau MJ. Essentials of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. Elsevier, 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10769] [Cited by in RCA: 10274] [Article Influence: 1027.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Spitzweg C, Nelson PJ, Wagner E, Bartenstein P, Weber WA, Schwaiger M, Morris JC. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS): novel applications for radionuclide imaging and treatment. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;28:T193-T213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kogai T, Brent GA. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS): regulation and approaches to targeting for cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135:355-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schlumberger M, Lacroix L, Russo D, Filetti S, Bidart JM. Defects in iodide metabolism in thyroid cancer and implications for the follow-up and treatment of patients. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:260-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xiao J, Yun C, Cao J, Ding S, Shao C, Wang L, Huang F, Jia H. A pre-ablative thyroid-stimulating hormone with 30-70 mIU/L achieves better response to initial radioiodine remnant ablation in differentiated thyroid carcinoma patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lawal IO, Nyakale NE, Harry LM, Lengana T, Mokgoro NP, Vorster M, Sathekge MM. Higher preablative serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level predicts radioiodine ablation effectiveness in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2017;38:222-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao T, Liang J, Guo Z, Li T, Lin Y. In Patients With Low- to Intermediate-Risk Thyroid Cancer, a Preablative Thyrotropin Level of 30 μIU/mL Is Not Adequate to Achieve Better Response to 131I Therapy. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:454-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Samuels MH, Veldhuis JD, Henry P, Ridgway EC. Pathophysiology of pulsatile and copulsatile release of thyroid-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and alpha-subunit. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:425-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roelfsema F, Veldhuis JD. Thyrotropin secretion patterns in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:619-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van der Spoel E, Roelfsema F, van Heemst D. Within-Person Variation in Serum Thyrotropin Concentrations: Main Sources, Potential Underlying Biological Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:619568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ehrenkranz J, Bach PR, Snow GL, Schneider A, Lee JL, Ilstrup S, Bennett ST, Benvenga S. Circadian and Circannual Rhythms in Thyroid Hormones: Determining the TSH and Free T4 Reference Intervals Based Upon Time of Day, Age, and Sex. Thyroid. 2015;25:954-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sviridonova MA, Fadeyev VV, Sych YP, Melnichenko GA. Clinical significance of TSH circadian variability in patients with hypothyroidism. Endocr Res. 2013;38:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Weeke J, Laurberg P. Diural TSH variations in hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;43:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Edmonds CJ, Hayes S, Kermode JC, Thompson BD. Measurement of serum TSH and thyroid hormones in the management of treatment of thyroid carcinoma with radioiodine. Br J Radiol. 1977;50:799-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Andersson CK, Elvborn M, Spetz JKE, Langen B, Forssell-Aronsson EB. Biodistribution of (131)I in mice is influenced by circadian variations. Sci Rep. 2020;10:15541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pacini F, Ladenson PW, Schlumberger M, Driedger A, Luster M, Kloos RT, Sherman S, Haugen B, Corone C, Molinaro E, Elisei R, Ceccarelli C, Pinchera A, Wahl RL, Leboulleux S, Ricard M, Yoo J, Busaidy NL, Delpassand E, Hanscheid H, Felbinger R, Lassmann M, Reiners C. Radioiodine ablation of thyroid remnants after preparation with recombinant human thyrotropin in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: results of an international, randomized, controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:926-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Burman KD, Van Nostrand D, Mete M, Jonklaas J, Wartofsky L. Radioiodine treatment of metastatic thyroid cancer: relative efficacy and side effect profile of preparation by thyroid hormone withdrawal versus recombinant human thyrotropin. Thyroid. 2012;22:310-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maxon HR, Thomas SR, Hertzberg VS, Kereiakes JG, Chen IW, Sperling MI, Saenger EL. Relation between effective radiation dose and outcome of radioiodine therapy for thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:937-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mallick U, Harmer C, Yap B, Wadsley J, Clarke S, Moss L, Nicol A, Clark PM, Farnell K, McCready R, Smellie J, Franklyn JA, John R, Nutting CM, Newbold K, Lemon C, Gerrard G, Abdel-Hamid A, Hardman J, Macias E, Roques T, Whitaker S, Vijayan R, Alvarez P, Beare S, Forsyth S, Kadalayil L, Hackshaw A. Ablation with low-dose radioiodine and thyrotropin alfa in thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1674-1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fard-Esfahani A, Emami-Ardekani A, Fallahi B, Fard-Esfahani P, Beiki D, Hassanzadeh-Rad A, Eftekhari M. Adverse effects of radioactive iodine-131 treatment for differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2014;35:808-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Iyer NG, Morris LG, Tuttle RM, Shaha AR, Ganly I. Rising incidence of second cancers in patients with low-risk (T1N0) thyroid cancer who receive radioactive iodine therapy. Cancer. 2011;117:4439-4446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pashnehsaz M, Takavar A, Izadyar S, Zakariaee SS, Mahmoudi M, Paydar R, Geramifar P. Gastrointestinal Side Effects of the Radioiodine Therapy for the Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma Two Days after Prescription. World J Nucl Med. 2016;15:173-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | University of Washington Clinical Center. I131 Radioactive Iodine To Treat Thyroid Cancer. [cited 17 September 2025]. Available from: https://www.uwmedicine.org/sites/default/files/2018-10/181019_Radiology_Preps_I131-Radioactive-Iodine-Therapy-Treat-Thyroid-Cancer.pdf. |

| 25. | Oh JM, Ahn BC. Molecular mechanisms of radioactive iodine refractoriness in differentiated thyroid cancer: Impaired sodium iodide symporter (NIS) expression owing to altered signaling pathway activity and intracellular localization of NIS. Theranostics. 2021;11:6251-6277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Dralle H, Elisei R, Smit JW, Wiersinga W; European Thyroid Cancer Taskforce. European consensus for the management of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma of the follicular epithelium. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:787-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1495] [Cited by in RCA: 1315] [Article Influence: 65.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Park S, Bang JI, Kim K, Seo Y, Chong A, Hong CM, Lee DE, Choi M, Lee SW, Oh SW. Comparison of Recombinant Human Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone and Thyroid Hormone Withdrawal for 131 I Therapy in Patients With Intermediate- to High-Risk Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med. 2024;49:e96-e104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Van Nostrand D. The benefits and risks of I-131 therapy in patients with well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1381-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cederroth CR, Albrecht U, Bass J, Brown SA, Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen J, Gachon F, Green CB, Hastings MH, Helfrich-Förster C, Hogenesch JB, Lévi F, Loudon A, Lundkvist GB, Meijer JH, Rosbash M, Takahashi JS, Young M, Canlon B. Medicine in the Fourth Dimension. Cell Metab. 2019;30:238-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/