Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.108187

Revised: May 16, 2025

Accepted: August 4, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 256 Days and 5.5 Hours

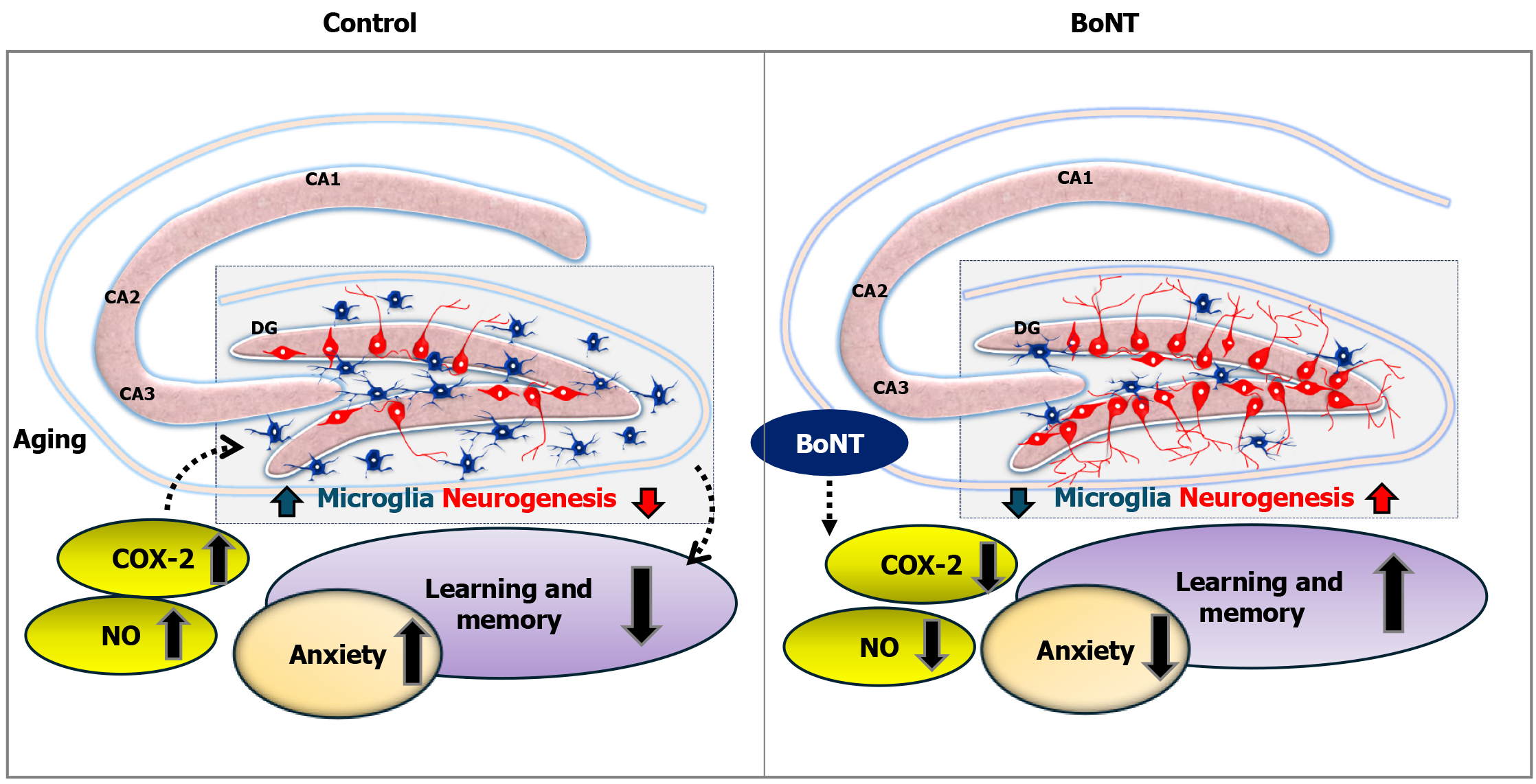

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) is widely recognized as an effective therapeutic agent for managing various neurological disorders, characterized by motor impairments and neuromuscular deficits. BoNT works by modulating the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. Recently, BoNT has been shown to enhance spatial memory and attenuate anxiety in experimental aging animals. While neurogenesis in the hippocampus contributes to cognitive properties, BoNT treatment could potentially influence the regulation of adult neurogenesis. As aging-associated microglial activation impairs neurogenesis, the anti-inflammatory properties of BoNT could be associated with the modulation of microglial activity, thereby enhancing cognitive function.

To investigate the neurogenic and microglial modulatory properties of BoNT in the hippocampus of aging experimental mice.

Experimental aging mice were administered BoNT and after four weeks, the animals were sacrificed. The brains were subjected to cryosections followed by immunohistochemical analysis to quantify doublecortin (DCX)-positive immature neurons, bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-neuronal nuclei (NeuN) double positive newly matured neurons and ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1)-positive microglia in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. In parallel, an additional set of animals was used to evaluate BoNT-mediated alterations in key inflammatory markers such as cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, and nitric oxide (NO) in hippocampal tissues.

The results revealed a significant increase in the number of DCX-positive immature neurons and BrdU-NeuN positive differentiated neurons in the hippocampus of the BoNT-treated group compared to the control. This enhancement in neurogenesis was accompanied by a marked reduction in the activated form of microglial cells, coupled with decreased mRNA expression of COX-2 and reduced NO levels in the hippocampus of BoNT-treated animals.

This study validates the proneurogenic and anti-neuroinflammatory properties of BoNT, which may underlie its procognitive effects. Hence, BoNT could be a promising therapeutic agent for treating various neurocognitive disorders.

Core Tip: Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) exerts pleiotropic effects, including notable neuroprotection. This study evaluated whether BoNT can ameliorate aging-related neuroinflammation and prevent the decline of hippocampal neurogenesis. BoNT treatment significantly reduced the number of activated microglia, accompanied by decreased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and diminished levels of nitric oxide. Therefore, the observed increase in doublecortin-positive immature neurons and bromodeoxyuridine - neuronal nuclei double-positive newly generated neurons in the hippocampus may signify the synergistic anti-inflammatory and neuroregenerative properties of BoNT. These findings suggest that BoNT treatment could be explored as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of dementia.

- Citation: Joseph JHM, Babu Deva Irakkam MP, Kandasamy M. Proneurogenic and microglial modulatory properties of botulinum neurotoxin in the hippocampus of aging experimental mice. World J Exp Med 2025; 15(4): 108187

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v15/i4/108187.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.108187

The production of new neurons in the hippocampus of the adult brain has been implicated in supporting cognitive functions, emotional regulation, and various aspects of mental abilities[1]. However, neurogenesis declines and becomes impaired with aging, chronic stress, anxiety, and neurodegenerative diseases due to elevated neuroinflammatory res

Notably, overexpression of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, an inflammatory marker, can activate microglia, which in turn produce more COX-2, creating a harmful feedback loop that further suppresses hippocampal neurogenesis[5,6]. Nitric oxide (NO), a free radical, has the ability to combine with superoxide anions to form peroxynitrite, a highly deleterious reactive nitrogen species[7]. Aberrant levels of NO have been associated with activated microglia-mediated neuroinflammatory responses in aging and various neuropathological conditions. Notably, elevated levels of NO have also been linked to impaired neurogenesis and memory loss[8]. Therefore, pharmacological strategies aimed at inhibiting microglial activation have been proposed as potential treatments to enhance neurogenesis and improve memory.

Implementation of a mild dose of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), a potent modulator of acetylcholine release, has been a well-established medical practice to treat migraine, neuropathic pain, neuromuscular disorders, and various movement disorders, including dystonia, cerebellar ataxia, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD)[9,10]. We have recently demonstrated that an intramuscular injection of BoNT reduces anxiety and improves learning and memory in experimental aging mice[11,12]. We hypothesize that the reported BoNT-mediated effects on cognitive improvement and anxiolytic properties might be associated with modulation of neurogenic processes and alterations in microglia populations. Therefore, this study was extended to examine the influence of therapeutic BoNT on the regulation of neurogenesis by assessing i) immunohistochemical levels of DCX-positive immature neurons, ii) differentiation potential of neural stem cells (NSCs) by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-neuronal nuclei (NeuN) double immunostaining and iii) distribution of Iba-1-expressing microglial cells in the hippocampus of experimental animals. Additionally, COX-2 expression was assessed using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and NO levels were measured using the Griess assay in the hippocampal tissues of aging experimental mice.

Male BALB/c mice aged 7-8 months (n = 12) were randomly assigned to two groups such as control (n = 6) and BoNT

The first set of experimental mice was subjected to transcardial perfusion under anaesthesia using sterile 0.9% NaCl (SRL, India) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (HiMedia, India)[13]. The dissected brains were postfixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4 °C. Subsequently, the brains were transferred to 30% sucrose (SRL, India). After a week, the brains were immersed in PolyFreeze tissue freezing medium (Sigma, United States) and subjected to sagittal cryosections of 30 micrometer (μm) thickness using a sliding microtome (Weswox, India) with dry ice. The serial sections of the brains were collected and stored in tubes filled with a cryoprotectant solution and maintained at -20 °C for subsequent immunohistochemical analyses.

For the immunohistochemistry analysis of DCX and Iba-1, two sets of brain sections were washed thrice in 1x Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 5 minutes each. Antigen retrieval was performed with 10 millimolar (mM) tri-sodium citrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) in 0.01% Triton X (HiMedia, India) at 65 °C for 2 hours. Following the washing step, the sections were exposed to 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (HiMedia, India) for 1 hour. Immunolabeling of immature neurons and microglia was performed by incubating the sections with rabbit anti-DCX antibody (Cell Signaling Technology 4604S, United States; 1:250 dilution) and rabbit anti-Iba-1 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology 17198S, United States, 1:250 dilution), respectively for 48 hours at 4 °C. After three washes for 5 minutes each, sections were incubated with a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with a fluorescent tag, DyLight 594 (Novus Biologicals NBP1-72732DL594, United States; 1:500 dilution) for 24 hours at 4 °C. Later, sections were preserved with coverslips using ProLong™ glass antifade mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) and dried. Then, blind codes were assigned to the slides to ensure that the evaluator remained unaware of the identities of the samples, thereby excluding bias in outcome assessments. The dentate gyrus (DG) region in the hippocampus was traced and immunolabeled cells were digitally captured using a fluorescence microscope (DM750, Leica Microsystems, Germany). DCX- and Iba-1-positive cells were quantified in six non-overlapping microscopic fields of the hippocampal DG using ImageJ with the cell counter plugin[13]. The average number of positive cells per field has been depicted in a bar graph.

Next, to evaluate the frequency of neuronal differentiation in the hippocampal DG, an extra set of brain sections was taken and washed in 1 × TBS three times for 10 minutes. After antigen retrieval, the brain sections were treated with 2N HCl (Finar, India) for 10 minutes at 37 °C on a shaker (Tarson, India). Then, the brain sections were treated with a 0.1 molar (M) borate buffer for another 10 minutes. After this step, the brain sections were washed three times in 1 × TBS for 10 minutes each at room temperature. Next, the brain sections were incubated in 3% BSA for 1 hour on a shaker at room temperature. Following the blocking step, two distinct primary antibodies were utilized: Mouse anti-BrdU (Novus Biologicals NBP2-32920, United States; 1:250 dilution) and rabbit anti-NeuN (Novus Biologicals NBP1-77686, United States; 1:250 dilution) for 48 hours at 4 °C. After removing the primary antibodies, the sections were thoroughly washed in 1 × TBS buffer. The brain sections were then treated with two different species-specific secondary antibodies: Sheep anti-mouse DyLight 488 (Novus Biologicals NBP1-72924, United States; 1:500 dilution) and goat anti-rabbit DyLight 594 (Novus Biologicals NBP1-72732DL594, United States; 1:500 dilution) at 4 °C for 24 hours. Then the secondary antibodies were removed and the sections were washed three times in 1 × TBS for 10 minutes each. In the end, the brain sections were arranged on double-frosted slides and allowed to dry overnight in the dark. Once fully dried, the sections were embedded in ProLong™ glass antifade mountant and kept in the dark to dry. The brain sections underwent double immunofluorescence imaging using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM 710, Carl Zeiss, Germany) at the central instrumentation facility of Bharathidasan University, and Z-stack optical images of the hippocampal DG were obtained to evaluate the colocalization of BrdU with NeuN. For assessing the frequency of neuronal differentiation, 25 BrdU-incorporated cells (green) in the hippocampal DG from each animal were analyzed. The BrdU-positive cells, which also exhibited co-labelling with NeuN (red), were classified as double-positive cells (yellow) and multiplied by four to estimate the percentage of double-positive cells, indicating the presence of newborn neurons[13].

The hippocampi were carefully separated from the brains of the second set of experimental mice under a dissection microscope. The total RNA from the hippocampi was isolated using the TRIzol (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) method. Further, the total RNA was quantified based on absorbance readings at 260 nm using a spectrophotometer and subjected to RT-PCR. For the synthesis of cDNA, 1 µg of total RNA was mixed with a total volume of 10 µL of cDNA synthesis kit (Takara, Japan) and was reverse-transcribed according to the manufacturer's protocol using a thermocycler (Veriti, Applied Biosystem, United States). Then 1 µl of cDNA was subjected to amplification in a total volume of 10 µL reaction mixture containing 2x master mix, forward and reverse primers, cDNA template, and nuclease-free water. The PCR conditions for COX-2 are as follows: Denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, (95 °C for 1 minute, annealing at 58 °C for 1 minute, extension at 72 °C for 1 minute) × 32 cycles, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes (Forward primer: 5’ AGAGTCACCACTACGTCA 3’and Reverse primer: 5’ ATCTGGGTCTACCTATGTA 3’). The conditions of PCR for the housekeeping gene, Tubulin are as follows: Denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, (95 °C for 1 minute, annealing at 60 °C for 1 minute, extension at 72 °C for 1 minute) × 32 cycles, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes (Forward primer: 5’ CATCGACAATGAAGCCCTCTA 3’ and reverse primer: 5’CTTTAACCTGGGAGCCCTAATG 3’). The PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The gel image was photo-documented using the gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, United States). The digital images of the gel were subjected to the densitometric assessment using ImageJ software. The mRNA expression levels of COX-2 were normalized with the expression of Tubulin in the control and BoNT-treated groups, respectively.

Hippocampal tissues were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline at a concentration of 100 mg tissue per mL and centrifuged at 12000 g for 15 minutes. The resulting supernatant was collected for protein quantification using the Lowry method. Equal volumes of the supernatant and Griess reagent (Sigma, United States) were added to a 96-well plate and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Absorbance was then measured at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer. Nitrite concentration was determined using a sodium nitrite standard curve.

Statistical Analysis was done using GraphPad Prism software. The values were represented as mean ± SD. The white-coloured bar represents the control group and the black-coloured bar represents the BoNT group. Student’s t-test was used to measure the statistical differences. The statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05 unless otherwise indicated.

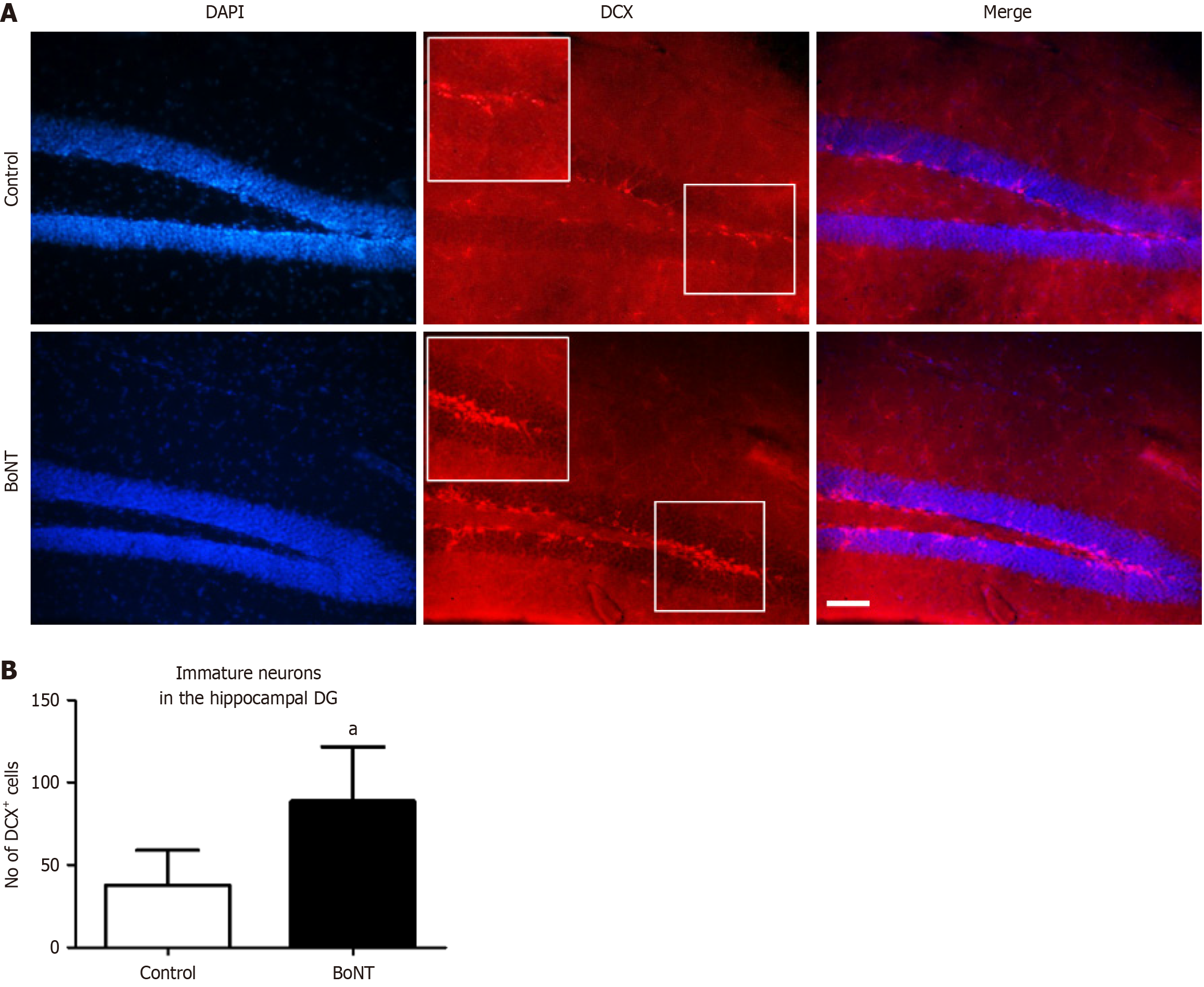

The quantification of the DCX-positive cells in the hippocampal DG region revealed a higher number of immature neurons in the brains of the BoNT-treated experimental mice compared to control (Control = 55 ± 15 vs BoNT = 89 ± 33) (Figure 1). Next, in the confocal microscopy-based assessment of fate determination of NSCs, BoNT treatment enhanced the percentage of BrdU-NeuN double positive neurons in the hippocampal DG region when compared to the control group. (Control = 70 ± 6 vs BoNT = 85 ± 5) (Figure 2).

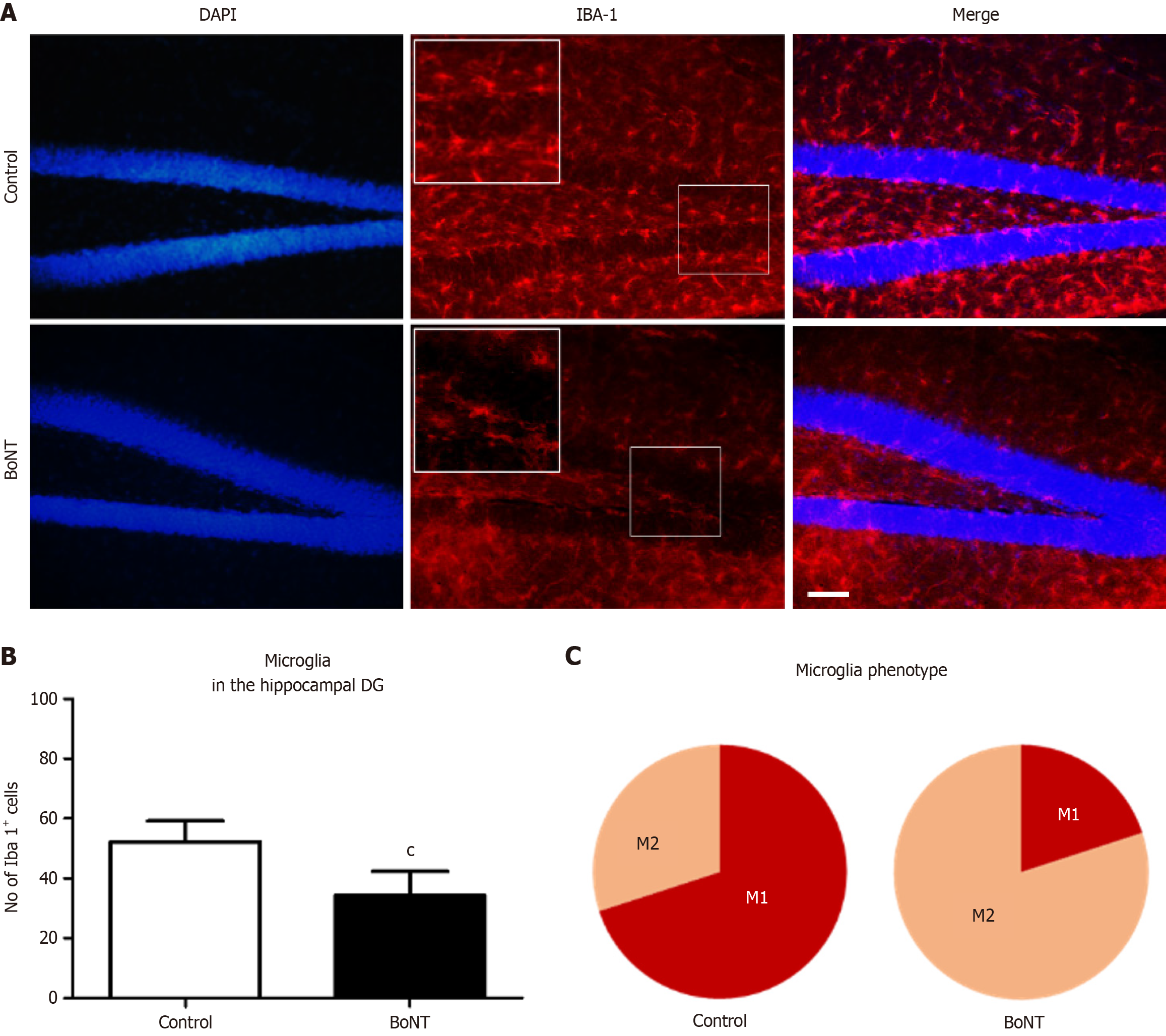

The immunohistochemical quantification of Iba-1 positive cells indicated a significant reduction in the number of microglia in the hippocampal DG of BoNT-treated mice compared to the control group (Control = 52 ± 7 vs BoNT = 34 ± 8). Further, in the assessment of morphological differences, a significant difference was observed in the phenotype of microglia in the DG region of hippocampus (% of M1 microglia: Control = 67 ± 11 vs BoNT = 19 ± 6; % of M2 microglia: Control = 33 ± 11 vs BoNT = 81 ± 6) (Figure 3).

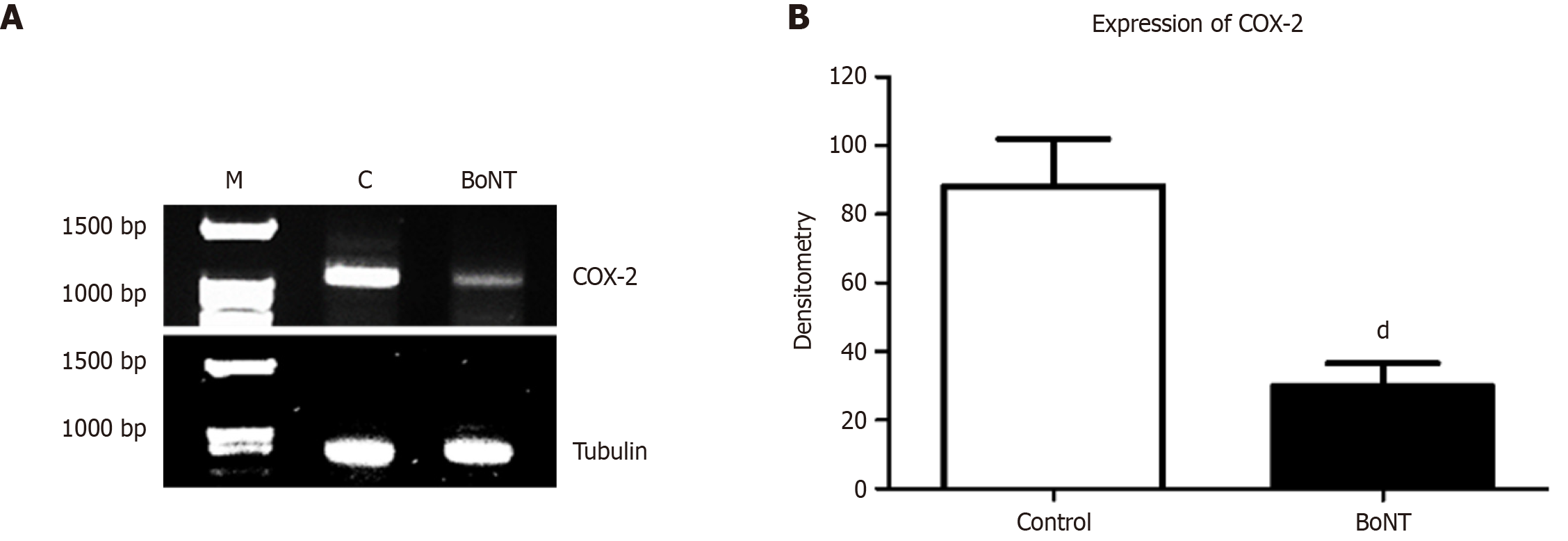

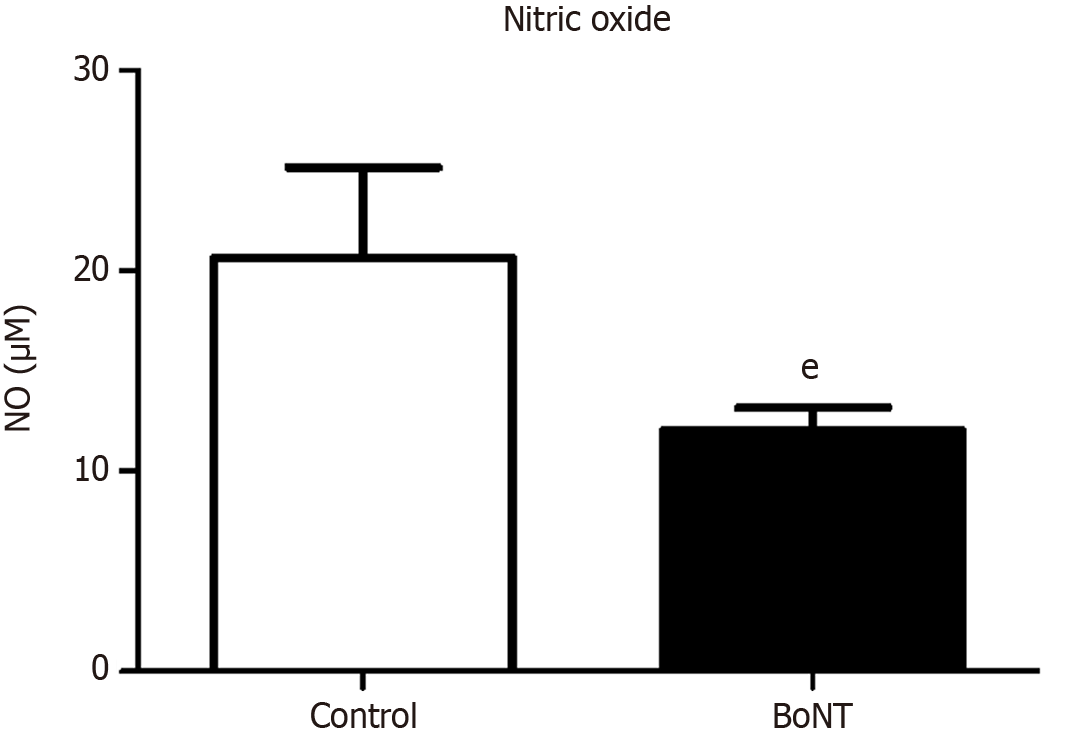

The densitometry assessment of the RT-PCR product indicated a marked reduction in mRNA expression of COX-2 in hippocampal tissues of the BoNT-treated group than the control group (Control = 88% ± 14 vs BoNT = 30% ± 7) (Figure 4). Results from the Griess assay indicated that NO levels were significantly reduced in the hippocampal extracts of BoNT-treated mice compared to control mice. (Control = 20.7 ± 3.7 vs BoNT = 12 ± 1.6) (Figure 5).

Sustaining hippocampal neurogenesis is important for cognitive functions in the physiological state[1]. Aging and neuroinflammation in brain disorders play a detrimental role in suppressing neurogenesis, accounting for progressive memory loss, anxiety, and depressive-like symptoms[14,15]. Thus, pharmacological interventions targeting neuroinflammatory pathways in the brain might aid in the development of potential therapies for neural regeneration. Recent reports indicate that administering a mild dose of BoNT via the intramuscular route diminishes innate anxiety and enhances learning and memory in experimental aging mice. This effect is considered to result from BoNT-mediated neuroprotection and antioxidant activities in the brains of the aging experimental mice[11,12]. In this study, we elucidate the pro-neurogenic mechanisms of BoNT, demonstrating its ability to increase the number of DCX-positive cells, which are considered to be immature neurons actively representing the ongoing neurogenic process in the hippocampus of the adult brain. These immature neurons originate from NSCs in the subgranular zone of the hippocampal DG, where they subsequently differentiate into newborn neurons, thereby supporting learning and memory[1]. Furthermore, an increased number of BrdU-labelled NSCs that differentiate into NeuN-positive neurons indicates the frequency of terminal differentiation of immature neurons, which can functionally integrate into the hippocampal neural circuitry[17]. Therefore, the observed increase in BrdU/NeuN-positive cells following BoNT treatment clearly validates its neurogenic potential, which may functionally contribute to enhanced neuroplasticity and corroborates earlier studies suggesting that BoNT improves learning and memory[12].

The mechanism by which BoNT enhances the neurogenic process could be speculated in two possible directions: Either through modulation of motor-sensory input or by suppressing neuroinflammation. One proposed mechanism is that BoNT indirectly modulates neurogenesis by altering peripheral muscle activity, thereby influencing afferent feedback and cortical excitability, which in turn can impact hippocampal neuroregenerative plasticity[18]. On the other hand, considering its well-established anti-inflammatory properties, BoNT-mediated suppression of microglial activity could facilitate a proneurogenic environment in the aging hippocampus by reducing the release of adverse factors such as NO, COX, and other pro-inflammatory mediators that interfere with cell cycle parameters of NSCs in the hippocampus. Notably, Wang et al[19] reported that following 48 hours of treatment with BoNT, SH-SY5Y cells exhibit induced ex

Pathogenic conditions such as PD have been associated with elevated levels of proinflammatory molecules[21]. BoNT administration has been reported to suppress the expression of proinflammatory genes in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced experimental models of PD[22]. In general, activated microglia represent the predominant source of neuroinflammation, contributing to the pathogenesis associated with behavioral deficits. Li et al[23] reported that 3 days of BoNT injections attenuated depressive-like behaviors in association with reduced activation of microglia in the hippocampus of a reserpine-induced mouse model of PD. While the destructive role of activated microglia is well established, aging and neurological diseases are often associated with a shift from the anti-inflammatory M2 to the pro-inflammatory M1 microglial phenotype as a contributing factor that disrupts neuroplasticity through the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 beta[24-26]. The simultaneous inhibition of M1 microglia and promotion of M2 microglia has been proposed to offer therapeutic benefits for neuroregeneration in the brain under adverse conditions[27]. Therefore, the BoNT-mediated shift from M1 to M2 microglia could be highly relevant for enhancing neurogenesis in the hippocampus, as it may reduce the secretion of neuroinflammatory and oxidative stress markers.

The increased level of COX-2 has been linked to the activation of microglia and induction of free radical mediated oxidative damage and impaired hippocampal neurogenesis. A study by Chuang et al[28] reported that intravesical administration of BoNT inhibited the expression of COX-2 and E-type prostanoid receptor-(EP)-4 which in turn at

Solabre Valois et al[16] reported that the incubation of hippocampal neurons with a non-toxic C-terminal region of the receptor-binding domain of heavy chain BoNT promoted the axonal outgrowth of dendritic arborizations via the activation of small Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate (Rac)-1 Rho guanosine triphosphate hydrolases and ex

In summary, this study provides compelling evidence that therapeutic BoNT can modulate hippocampal neurogenesis and suppress neuroinflammation, highlighting its emerging role as a therapeutic agent for neurological disorders associated with memory loss, beyond its traditional neuromuscular applications.

Hippocampal neurogenesis is essential for regulating mood and memory. Whereas reduced hippocampal neurogenesis has been linked to anxiety and memory deficits. BoNT treatment facilitates proneurogenic and anti-inflammatory effects in the hippocampal DG of aging experimental animals, accompanied by a marked reduction in COX-2 expression. The enhanced neurogenic process and neuroprotection may serve as the underlying foundation for the procognitive and anxiolytic effects of BoNT treatment. Thus, BoNT holds promise for treating anxiety, neurodegenerative disorders, and dementia (Figure 6).

The authors would like to thank Prof. Anusuyadevi Muthuswamy for their helpful scientific discussions and suggestions on the plan and protocol of the manuscript. Authors acknowledge UGC-SAP and DST-FIST for the infrastructure of the Department of Animal Science, Bharathidasan University. The authors acknowledge University Science Instrumentation Centre (USIC)-BDU for providing access to the confocal microscopic facility funded by DST-PURSE (Phases 1 and 2). The authors thank Dr. Muthu Kumar, USIC-BDU, for the excellent technical support with the confocal microscopy.

| 1. | Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2119] [Cited by in RCA: 2042] [Article Influence: 136.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Couillard-Despres S, Winner B, Schaubeck S, Aigner R, Vroemen M, Weidner N, Bogdahn U, Winkler J, Kuhn HG, Aigner L. Doublecortin expression levels in adult brain reflect neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 701] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Davies DS, Ma J, Jegathees T, Goldsbury C. Microglia show altered morphology and reduced arborization in human brain during aging and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:795-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fornari Laurindo L, Aparecido Dias J, Cressoni Araújo A, Torres Pomini K, Machado Galhardi C, Rucco Penteado Detregiachi C, Santos de Argollo Haber L, Donizeti Roque D, Dib Bechara M, Vialogo Marques de Castro M, de Souza Bastos Mazuqueli Pereira E, José Tofano R, Jasmin Santos German Borgo I, Maria Barbalho S. Immunological dimensions of neuroinflammation and microglial activation: exploring innovative immunomodulatory approaches to mitigate neuroinflammatory progression. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1305933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vijitruth R, Liu M, Choi DY, Nguyen XV, Hunter RL, Bing G. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates microglial activation and secondary dopaminergic cell death in the mouse MPTP model of Parkinson's disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nagano T, Tsuda N, Fujimura K, Ikezawa Y, Higashi Y, Kimura SH. Prostaglandin E(2) increases the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in cultured rat microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 2021;361:577724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1424-C1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4009] [Cited by in RCA: 3891] [Article Influence: 129.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bahdar ZI, Abu-El-Rub E, Almazari R, Alzu'bi A, Al-Zoubi RM. The molecular mechanism of nitric oxide in memory consolidation and its role in the pathogenesis of memory-related disorders. Neurogenetics. 2025;26:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nigam PK, Nigam A. Botulinum toxin. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kandasamy M. Perspectives for the use of therapeutic Botulinum toxin as a multifaceted candidate drug to attenuate COVID-19. Med Drug Discov. 2020;6:100042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yesudhas A, Radhakrishnan RK, Sukesh A, Ravichandran S, Manickam N, Kandasamy M. BOTOX® counteracts the innate anxiety-related behaviours in correlation with increased activities of key antioxidant enzymes in the hippocampus of ageing experimental mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;569:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yesudhas A, Roshan SA, Radhakrishnan RK, Abirami GPP, Manickam N, Selvaraj K, Elumalai G, Shanmugaapriya S, Anusuyadevi M, Kandasamy M. Intramuscular Injection of BOTOX® Boosts Learning and Memory in Adult Mice in Association with Enriched Circulation of Platelets and Enhanced Density of Pyramidal Neurons in the Hippocampus. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:2856-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vergil Andrews JF, Selvaraj DB, Kumar A, Roshan SA, Anusuyadevi M, Kandasamy M. A Mild Dose of Aspirin Promotes Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Working Memory in Experimental Ageing Mice. Brain Sci. 2023;13:1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hurley LL, Tizabi Y. Neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and depression. Neurotox Res. 2013;23:131-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ahmad MA, Kareem O, Khushtar M, Akbar M, Haque MR, Iqubal A, Haider MF, Pottoo FH, Abdulla FS, Al-Haidar MB, Alhajri N. Neuroinflammation: A Potential Risk for Dementia. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Solabre Valois L, Shi VH, Bishop P, Zhu B, Nakamura Y, Wilkinson KA, Henley JM. Neurotrophic effects of Botulinum neurotoxin type A in hippocampal neurons involve activation of Rac1 by the non-catalytic heavy chain (HC(C)/A). IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2021;10:196-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kempermann G, Gast D, Kronenberg G, Yamaguchi M, Gage FH. Early determination and long-term persistence of adult-generated new neurons in the hippocampus of mice. Development. 2003;130:391-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 734] [Cited by in RCA: 771] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Luvisetto S, Marinelli S, Rossetto O, Montecucco C, Pavone F. Central injection of botulinum neurotoxins: behavioural effects in mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15:233-240. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wang L, Ringelberg CS, Singh BR. Dramatic neurological and biological effects by botulinum neurotoxin type A on SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, beyond the blockade of neurotransmitter release. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;21:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hwang S, Seo M, Lee TH, Lee HJ, Park JW, Kwon BS, Nam K. Comparison of the Effects of Botulinum Toxin Doses on Nerve Regeneration in Rats with Experimentally Induced Sciatic Nerve Injury. Toxins (Basel). 2023;15:691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pajares M, I Rojo A, Manda G, Boscá L, Cuadrado A. Inflammation in Parkinson's Disease: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cells. 2020;9:1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 520] [Cited by in RCA: 554] [Article Influence: 92.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ham HJ, Yeo IJ, Jeon SH, Lim JH, Yoo SS, Son DJ, Jang SS, Lee H, Shin SJ, Han SB, Yun JS, Hong JT. Botulinum Toxin A Ameliorates Neuroinflammation in the MPTP and 6-OHDA-Induced Parkinson's Disease Models. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2022;30:90-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li Y, Yin Q, Li Q, Huo AR, Shen TT, Cao JQ, Liu CF, Liu T, Luo WF, Cong QF. Botulinum neurotoxin A ameliorates depressive-like behavior in a reserpine-induced Parkinson's disease mouse model via suppressing hippocampal microglial engulfment and neuroinflammation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44:1322-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Woodburn SC, Bollinger JL, Wohleb ES. The semantics of microglia activation: neuroinflammation, homeostasis, and stress. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 528] [Article Influence: 105.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang G, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Li D, Liu J, Zhang F. Age-Associated Dopaminergic Neuron Loss and Midbrain Glia Cell Phenotypic Polarization. Neuroscience. 2019;415:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gao J, Li L. Enhancement of neural regeneration as a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer's disease (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2023;26:444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yang Z, Liu B, Yang LE, Zhang C. Platycodigenin as Potential Drug Candidate for Alzheimer's Disease via Modulating Microglial Polarization and Neurite Regeneration. Molecules. 2019;24:3207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chuang YC, Yoshimura N, Huang CC, Wu M, Chiang PH, Chancellor MB. Intravesical botulinum toxin A administration inhibits COX-2 and EP4 expression and suppresses bladder hyperactivity in cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis in rats. Eur Urol. 2009;56:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | von Bernhardi R, Eugenín-von Bernhardi L, Eugenín J. Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kandasamy M. Theta rhythm as a real-time quantitative marker for non-invasive analysis of adult neurogenesis in the intact brain. J Biol Methods. 2025;e99010061. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/