Published online Dec 19, 2019. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v9.i2.14

Peer-review started: May 20, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: September 5, 2019

Accepted: November 20, 2019

Article in press: November 20, 2019

Published online: December 19, 2019

Processing time: 215 Days and 5.6 Hours

ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels were originally found in cardiac myocytes by Noma in 1983. KATP channels were formed by potassium ion-passing pore-forming subunits (Kir6.1, Kir6.2) and regulatory subunits SUR1, SU2A and SUR2B. A number of cells and tissues have been revealed to contain these channels including hepatocytes, but detailed localization of these subunits in different types of liver cells was still uncertain.

To investigate the expression of KATP channel subunits in rat liver and their localization in different cells of the liver.

Rabbit anti-rat SUR1 peptide antibody was raised and purified by antigen immunoaffinity column chromatography. Four of Sprague-Dawley rats were used for liver protein extraction for immunoblot analysis, seven of them were used for immunohistochemistry both for the ABC method and immunofluorescence staining. Four of Wistar rats were used for the isolation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and Kupffer cells for both primary culture and immunocytochemistry.

Immunoblot analysis showed that the five kinds of KATP channel subunits, i.e. Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B, were detected in liver. Immunohistochemical staining showed that Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 were weakly to moderately expressed in parenchymal cells and sinusoidal lining cells, while SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B were mainly localized to sinusoidal lining cells, such as HSCs, Kupffer cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells. Immunoreactivity for SUR2A and SUR2B was expressed in the hepatocyte membrane. Double immunofluorescence staining further showed that the pore-forming subunits Kir6.1 and/or Kir6.2 colocalized with GFAP in rat liver sections and primary cultured HSCs. These KATP channel subunits also colocalized with CD68 in liver sections and primary cultured Kupffer cells. The SUR subunits colocalized with GFAP in liver sections and colocalized with CD68 both in liver sections and primary cultured Kupffer cells. In addition, five KATP channel subunits colocalized with SE-1 in sinusoidal endothelial cells.

Observations from the present study indicated that KATP channel subunits expressed in rat liver and the diversity of KATP channel subunit composition might form different types of KATP channels. This is applicable to hepatocytes, HSCs, various types of Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells.

Core tip: ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels have been found to be ubiquitously distributed in a variety of cell types and tissues, but the present study revealed that five kinds of KATP channel subunits are expressed in rat liver by applying western blot analysis, immunohistochemistry, and immunocytochemistry of rat liver tissue and primary cultured cells. These KATP channel subunits were not only localized in hepatocytes but also in sinusoidal cells, such as hepatic stellate cells, Kupffer cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells. This was demonstrated using specific marker labelling, such as GFAP for hepatic stellate cells, CD68 for Kupffer cells, and SE-1 for sinusoidal endothelial cells. The wide diversity of KATP channel subunit compositions in rat liver might correspond to their various functions in hepatocytes and sinusoidal cells.

- Citation: Zhou M, Yoshikawa K, Akashi H, Miura M, Suzuki R, Li TS, Abe H, Bando Y. Localization of ATP-sensitive K+ channel subunits in rat liver. World J Exp Med 2019; 9(2): 14-31

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315X/full/v9/i2/14.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v9.i2.14

ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels were found ubiquitously distributed in a variety of cells and tissues[1], such as pancreatic β cells[2-5], skeletal muscle[6], neurons and glial cells[7-9], kidney[10-13], and liver[14,15]. KATP channels close at high concentrations of intracellular ATP and open at low concentrations during ischemia[7,16-18], and couple altered energy metabolism with membrane potential[19,20]. KATP channels are hetero-octamers composed of two kinds of subunits: the four pore-forming subunit Kir6.x (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2), and the four regulatory subunit sulfonylurea receptor SUR (SUR1, SUR2A, or SUR2B)[21-24]. Their physiological and pharmacological functions depend on their subunit compositions[25-27]. In the hypothalamus, glucose homeostasis is controlled by glucagon and catecholamine, which are counter-regulatory hormones, and these functions are involved with KATP channels[26,28]. The liver is also an organ that directly takes part in glucose metabolism with changes in intracellular ATP (ATPi) concentrations during which KATP channels are quite sensitive. The mRNA of KATP channels in liver is detected by northern blot analysis[14], KATP channels play roles in regulating hepatocyte proliferation in primary rat hepatocytes[29]. However, there are no detailed references on the localization of KATP channel molecules and their functions in the liver with respect to hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), Kupffer cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs). In addition to glucose metabolism, the liver has important functions in regeneration after injury and partial hepatectomy, as well as some functions of immune defense because of Kupffer cells. HSCs are localized between SECs and hepatocytes, and are activated during liver injury, producing many growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines, and also excessive extracellular matrix. They are also known as one of the reasons for hepatic fibrosis after liver injury recovery[30-33]. We are interested in clarifying the relationships between KATP channel subunits and hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, HSCs, and SECs in the liver during normal and pathological conditions.

Since there is no detailed information on the localization of KATP channel molecules in the liver with respect to different cells, we focused on the expression and localization of these KATP channel subunits in liver, and supply morphological data to help understand what functions they could play in parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells.

Sprague-Dawley and Wistar rats were supplied by CLEA Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). This study was conducted according to the protocols of the Animal Research Committee of Akita University. We handled the animals according to the Guidelines of Akita University for Animal Experimentation. Rats used in this study were kept under constant environmental conditions in group cages (2-3 rats per cage) with 12 h light/dark cycles, and normal food and water were given.

Male SD rats (4-8 wk) under deep anesthesia were perfused through the left ventricle with cold Zamboni fixatives (2 g paraformaldehyde solved in 15 mL of saturated picric acid and Karasson Schwlt’s phosphate buffer solution added to make 100 mL). Liver tissue blocks were taken and further fixed in the same fixative for 6 h at 4 °C, and then changed to 30% sucrose in PBS until they sank to the bottom. No-fixed liver tissue was also taken for GFAP immunostaining. Cryosections were cut 10 µm thick with a Leica CM1950 cryostat, thaw-mounted on glass slides (MAS-coated, Matsunami Industries, Kishiwada, Japan) and stored at -20 °C before use. Liver samples for immunoblot analysis were directly taken out without fixation, put into dry ice powder, and stored at -80 °C until use.

Male Wistar rats (400-500 g body mass), maintained on a normal chow diet, were used. Rats were perfused via the portal vein in situ with pre-perfusion solution (Ca2+/Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 10 mM hydroxyethyl piperazine ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 0.5 mM EGTA, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, and 5 mM glucose; pH 7.2) for 5 min at 37 °C, followed by collagenase solution (HBSS) containing 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM CaCl2, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, and 0.5 mg/mL bacterial collagenase; pH 7.5) for 15 min at 37 °C at a flow rate of 15 mL/min. Liver digested by collagenase solution was excised, dispersed, and filtered through stainless mesh. Isolation of HSCs and Kupffer cells was performed based on cell size and density[34]. To eliminate most of the parenchymal cells, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 50 × g for 1 min. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 50 × g for 3 min. The supernatant of the second run was centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min to pellet non-parenchymal cells. The non-parenchymal cells in the pellet were further centrifuged at 700 × g for 30 min in 25% (v/v) Percoll PLUS solution (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, United States). HSCs were enriched in the supernatant, and Kupffer cells were mostly enriched in the pellet with other types of cells. The supernatant enriched in HSCs was diluted with 2 volumes of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min to wash out Percoll PLUS. All centrifugations were performed at 4 °C. The cell fractions enriched in HSCs and Kupffer cells were suspended in culture media (DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin), and then plated on glass-bottom dishes coated with poly-L-lysine (Matsunami Glass, Osaka, Japan). Twelve to sixteen hours later, the cells were washed to remove debris, and then used for immunocytochemistry.

Rabbit anti-rat SUR1 antibody was generated by immunization with a synthetic 22-mer peptide, NH2-DSALVLSPAARNCSLSQECALD-(COOH) (Biologica Co. Nagoya, Japan), which corresponds to amino acid residues of 1038-1059 of rat SUR1 (GenBank Accession No. L40624). Antiserum was purified by peptide antigen immunoaffinity column chromatography.

SDS/PAGE was performed as the procedure of Laemmli. Proteins were treated with modified sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 25% glycerol, 0.01% Bromophenol blue, and 10% 2-mercaptoethanol). After electrophoresis, proteins (10 µg/lane) were subsequently transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (NENTM Life Science, Boston, MA, United States) using a semi-dry transfer unit (Hoefer TE70 series; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). After blocking with 5% BLOT-QuickBlocker (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, CA, United States) in PBS at room temperature overnight, immunoblotting was carried out by incubating the PVDF membranes with polyclonal goat anti-human Kir6.1 and/or Kir6.2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit anti-rat SUR1, SUR2A and/or SUR2B antibody[35], each diluted to 1:1000, respectively, for 1 h at room temperature. Following thorough washing with PBS-T (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20), the PVDF membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (NA9340; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology, England), or HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (AP180P), each diluted 1:3000. Signals were visualized with chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology, England), and PVDF membranes were exposed to XOMAT film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, United States) in the dark room. Negative controls and specificity verification of the SUR1 antibody were performed using the antigen peptide preabsorption test.

After air drying for 30 min, cryosections of liver were treated with 0.3% Tween-20 in PBS for 45 min at room temperature. Sections were blocked either with 5% normal rabbit serum or 5% normal goat serum for 30 min, and then incubated with goat anti-human Kir6.1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-human Kir6.2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit anti-rat SUR1, SUR2A, and/or SUR2B, each diluted at 1:500. After washing with PBS three times, the biotinylated rabbit anti-goat IgG, or biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, were applied to sections. As a negative control, the immunoreactive solution was prepared without the primary antibody, and an absorption test was also confirmed by pre-incubation with peptide antigen.

To show whether the pore-forming subunits Kir6.1 and/or Kir6.2 are colocalized with the regulatory subunits SUR1, SUR2A and/or SUR2B in the liver, sections were incubated with a mixture of goat anti-human Kir6.1 and rabbit anti-rat SUR1, and/or anti-rat SUR2A, and/or SUR2B; or a mixture of goat anti-human Kir6.2 with rabbit anti-rat SUR1, SUR2A and/or SUR2B antibody, each diluted 1:500, respectively, for 12 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with a mixture of Alexa488-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (A21432; Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) and Alexa594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A21207; Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR), each diluted 1:200.

To determine whether the KATP channel subunit molecules colocalize with HSCs, Kupffer cells and/or SECs, sections were incubated with a mixture of mouse anti-GFAP (marker of HSCs), or incubated with a mixture of mouse anti-CD68 (marker of Kupffer cells), and/or incubated with a mixture of mouse anti-SE-1 antibody (marker of SECs) and one of the KATP channel subunit antibodies, such as goat anti-human Kir6.1, goat anti-human Kir6.2, rabbit anti-rat SUR1, rabbit anti-rat SUR2A, and/or rabbit anti-rat SUR2B, respectively, each diluted 1:200. After thoroughly washing with PBS, the liver sections were then incubated for 30 min with a mixture of the appropriate fluorescent Alexa 488 or Alexa 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) each diluted 1:200. Finally, the sections stained above were mounted with aqueous mounting medium (Thermo, Pittsburgh, PA, United States).

Primary cultured HSCs and Kupffer cells were fixed with Zamboni’s fixatives for 5 min and then double immunofluorecent staining was carried out as (1) mouse anti-GFAP with one of the antibodies of the pore-forming subunits Kir6.1 and/or Kir6.2, and/or one of the antibodies of the regulatory subunits SUR1, SUR2A and/or SUR2B; (2) mouse anti-CD68 with one of the antibodies of goat anti-human Kir6.1, and/or Kir6.2, and rabbit anti-rat SUR1, SUR2A and/or SUR2B; (3) goat anti-human Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 with one of the antibodies of rabbit anti-rat SUR1, SUR2A, and/or SUR2B. After thoroughly washing with PBS, the dishes were incubated for 30 min with the appropriate fluorescent Alexa 488- or Alexa 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) each diluted 1:200. Fluorescence image signals were acquired using an Olympus microscope (BX51; Tokyo, Japan) and a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR2A and SUR2B were expressed in rat liver (Figure 1A). For the anti-SUR1 antibody, immunoblot analysis showed that the molecular weight of SUR1 was about 100 kDa with some weak small bands below. After preincubation with immunizing peptide from which the antibody was raised, the SUR1 band disappeared (Figure 1B, +peptide).

Immunohistochemistry revealed that immunoreactivity for Kir6.1 was widely and weakly observed in hepatocytes in the hepatic lobules (Figure 2A), as well as in the endothelia of the central vein, the branches of the hepatic artery, and the portal vein at the portal area (Figure 2C). The intensity of immunoreactivity was gradually decreased along the liver plate from the central vein to the distal area (Figure 2A). Weak immunoreactivity for Kir6.1 was expressed in the cell membrane and cytoplasm of hepatocytes. Under high magnification, the Kir6.1 protein was observed as punctate immunoreactive products in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes and sinusoidal lining cells (Figure 2B). When the anti-Kir6.1 antibody was omitted or preincubated with antigen peptide, significant immunoreactivity could not be observed (Figure 2D).

Immunoreactivity for Kir6.2 was also weakly distributed in the hepatic lobule (Figure 3A) and in the endothelium of the central vein, the branches of the hepatic artery, and the portal vein in the portal area (Figure 3C). The intensity of immunoreactivity was gradually decreased along the liver plate (Figure 3A and B). Weak immunoreactivity for Kir6.2 was expressed in the cell membrane and cytoplasm of hepatocytes. Under high magnification, the immunoreactive products for Kir6.2 could be observed as rough granules in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes and sinusoidal lining cells (Figure 3B). When the anti-Kir6.2 antibody was omitted or pre-incubated with immunizing antigen peptides, no significant immunoreactivity could be observed (Figure 3D).

Immunoreactivity for SUR1 was quite different from that for Kir6.1 and Kir6.2. Moderate immunoreactivity for SUR1 was distributed in small sinusoidal lining cells with round, ovular, or spindle shapes beside the liver plate (Figure 4A and B), and also in the endothelial cells of the branches of hepatic artery and portal veins at the portal area (Figure 4C). The intensity was not decreased along the liver plate. In hepatocytes, the immunoreactivity for SUR1 was hardly observed in the cytoplasm, and only faintly in the cell membrane (Figure 4B). When the anti-SUR1 antibody was omitted or preincubated with immunizing peptide antigen, the positive immunoreactivity disappeared (Figure 4D).

Immunoreactivity for SUR2A was distributed in the hepatic lobule with moderate intensity around the central vein (Figure 5A), and gradually attenuated along the liver plate. It was mainly localized in irregular- or spindle-shaped cells in the sinusoidal lining (Figure 5B). Weak immunoreactivity for SUR2A was expressed in the cell membrane of hepatocytes. In the portal area, it was weakly expressed in the branches of hepatic arteries and portal veins (Figure 5C).

Immunoreactivity for SUR2B was widely and weakly distributed in the hepatic lobule (Figure 6A). It was mainly localized in small round or oval-shaped cells in the sinusoidal lining. Weak immunoreactivity for SUR2B was expressed in the cell membrane of hepatocytes (Figure 6B). The intensity of immunoreactivity was gradually decreased along the liver plate from the central vein to the distal area (Figure 6A). In the portal area, it was moderately expressed in the branches of the hepatic artery and portal vein, and was especially intense in the bile duct (Figure 6C). When the anti-SUR2A or anti-SUR2B antibodies were omitted or preincubated with each immunizing peptide antigen, the immunoreactivity for SUR2A and/or SUR2B disappeared (Figures 5D and 6D).

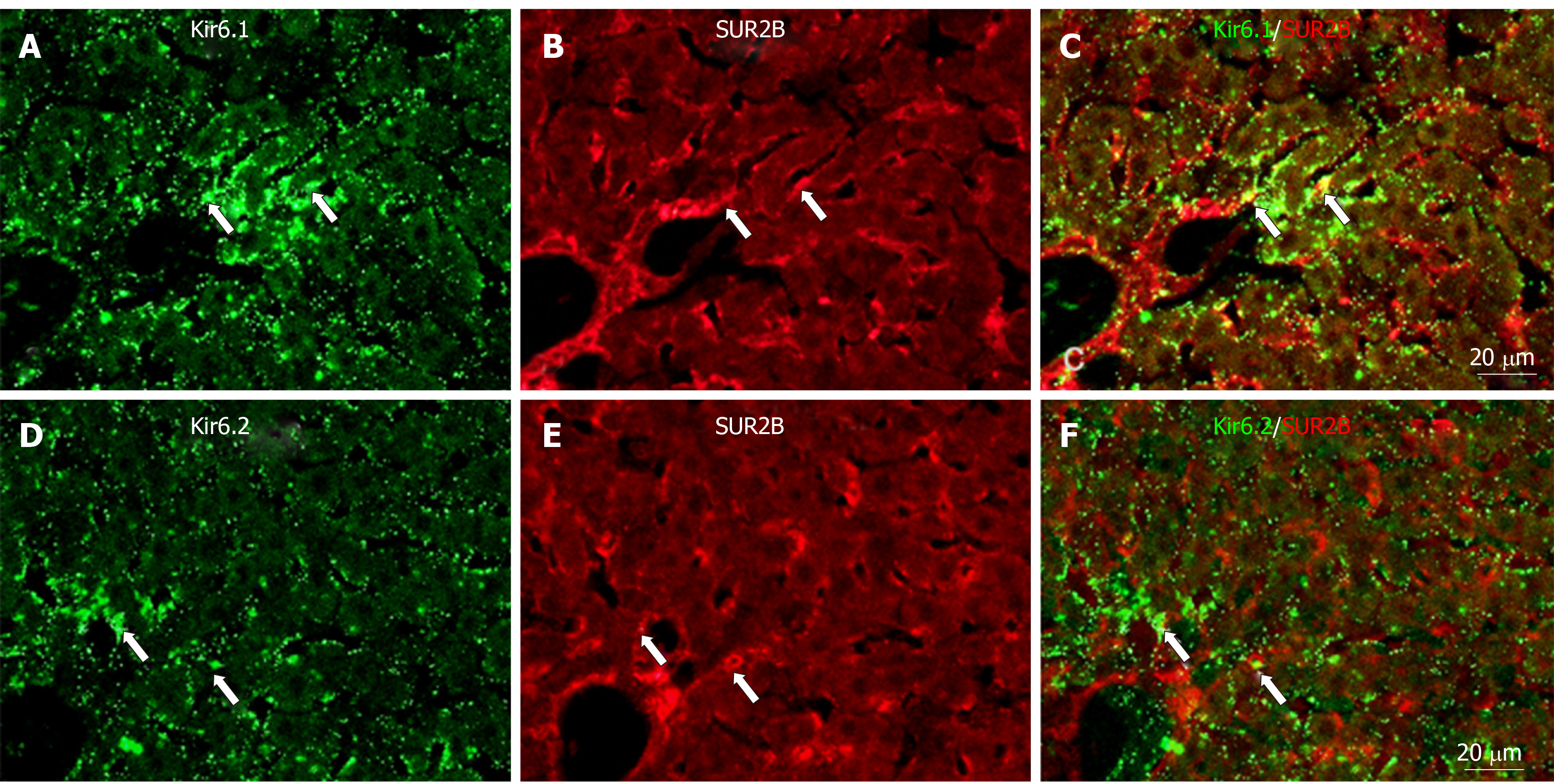

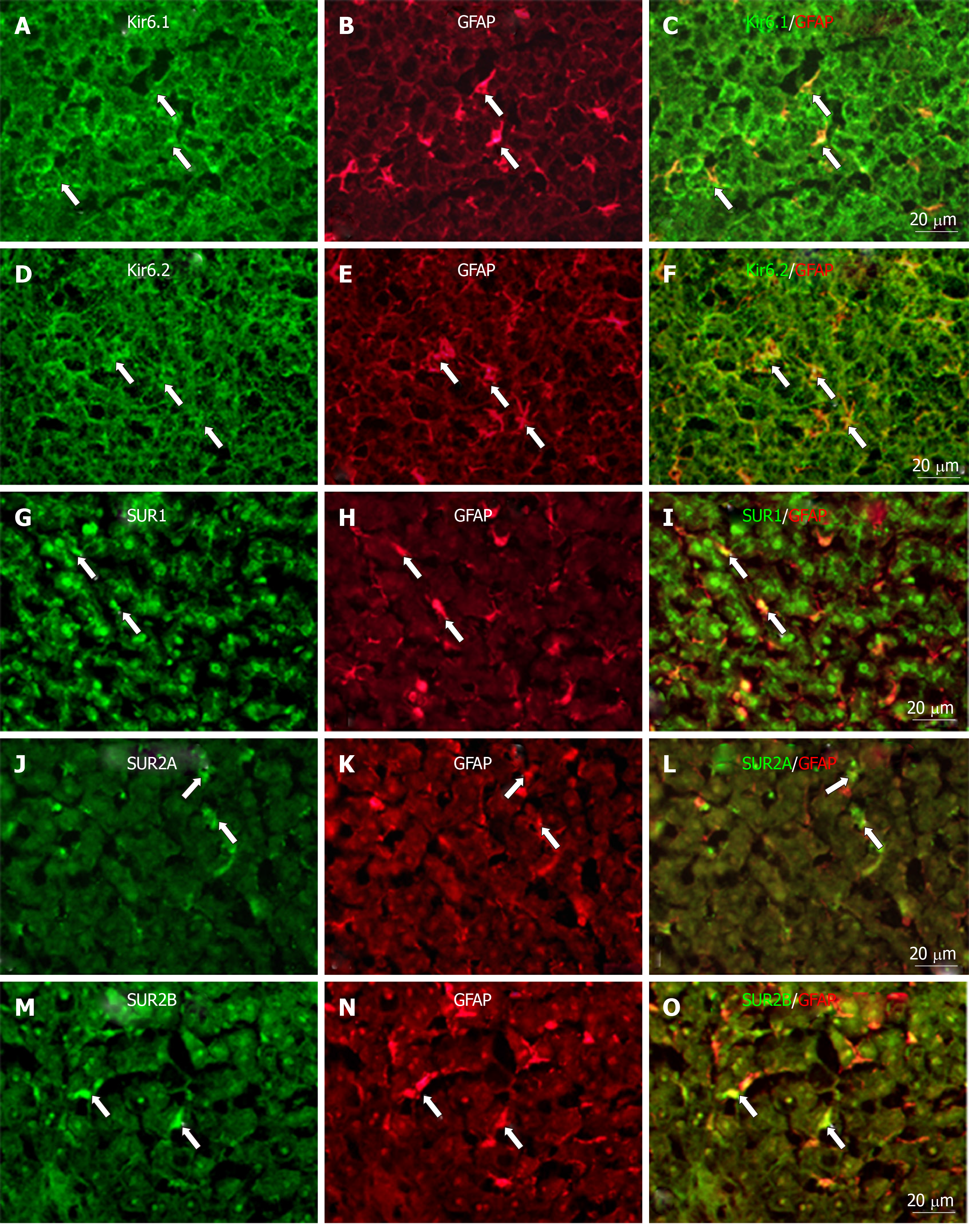

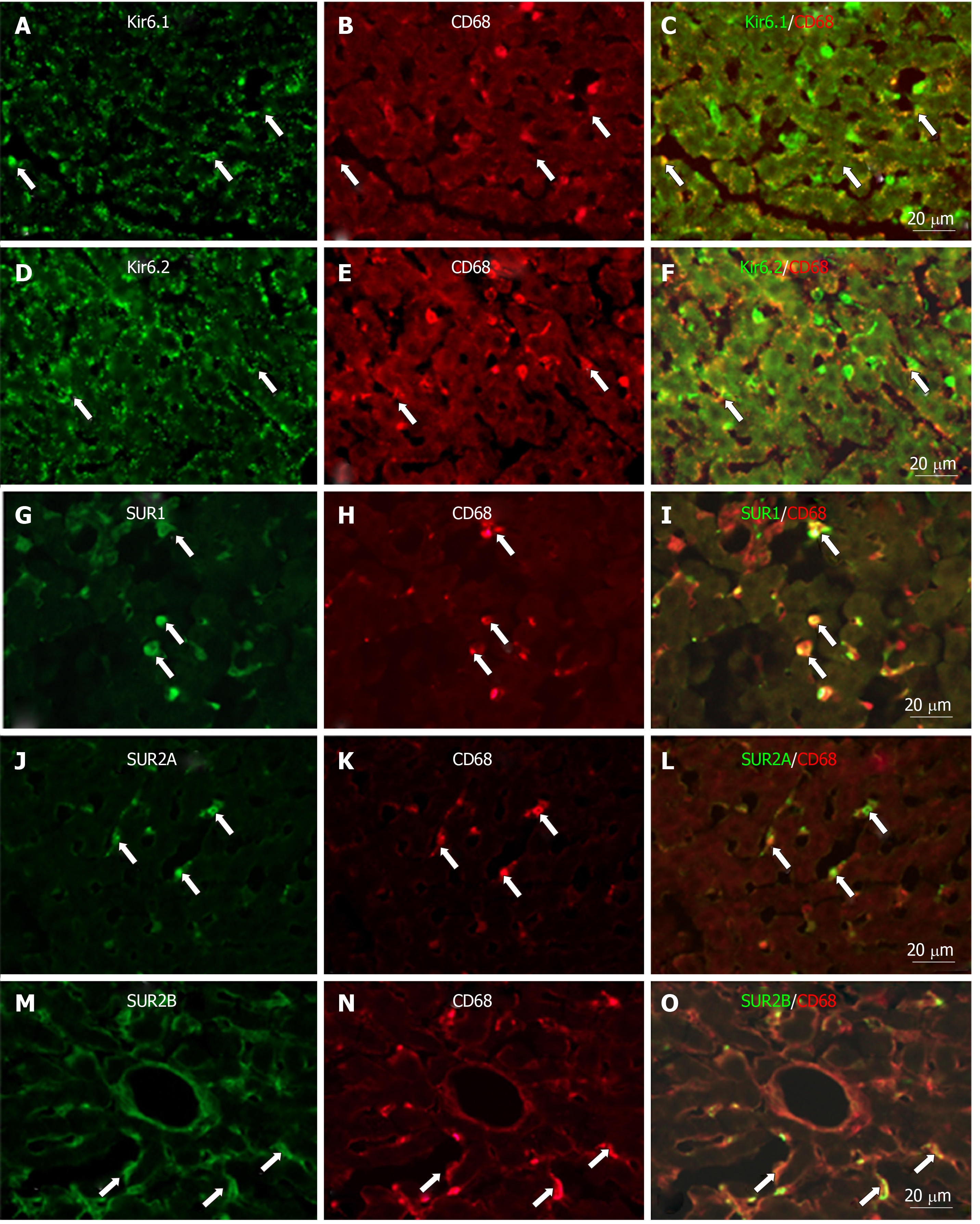

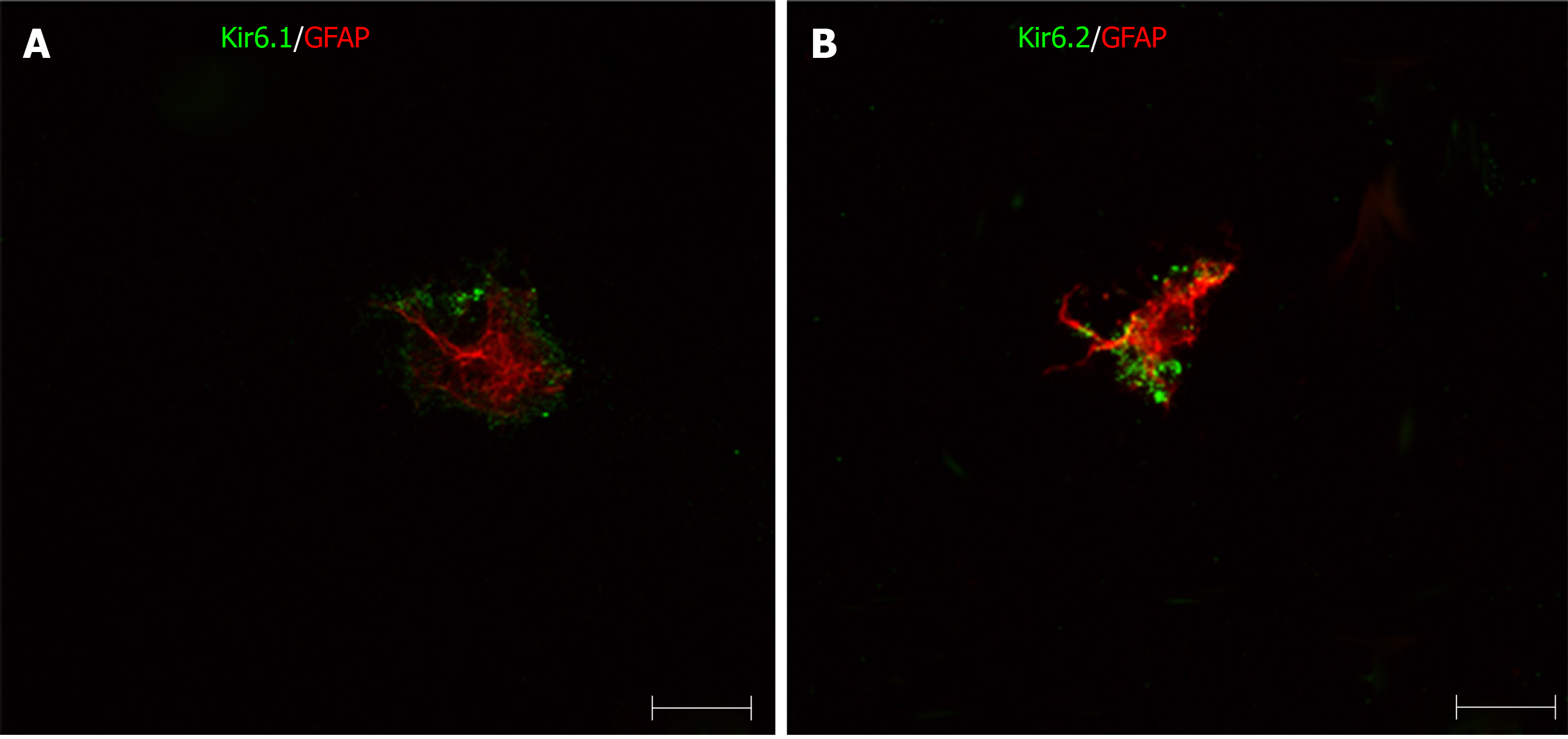

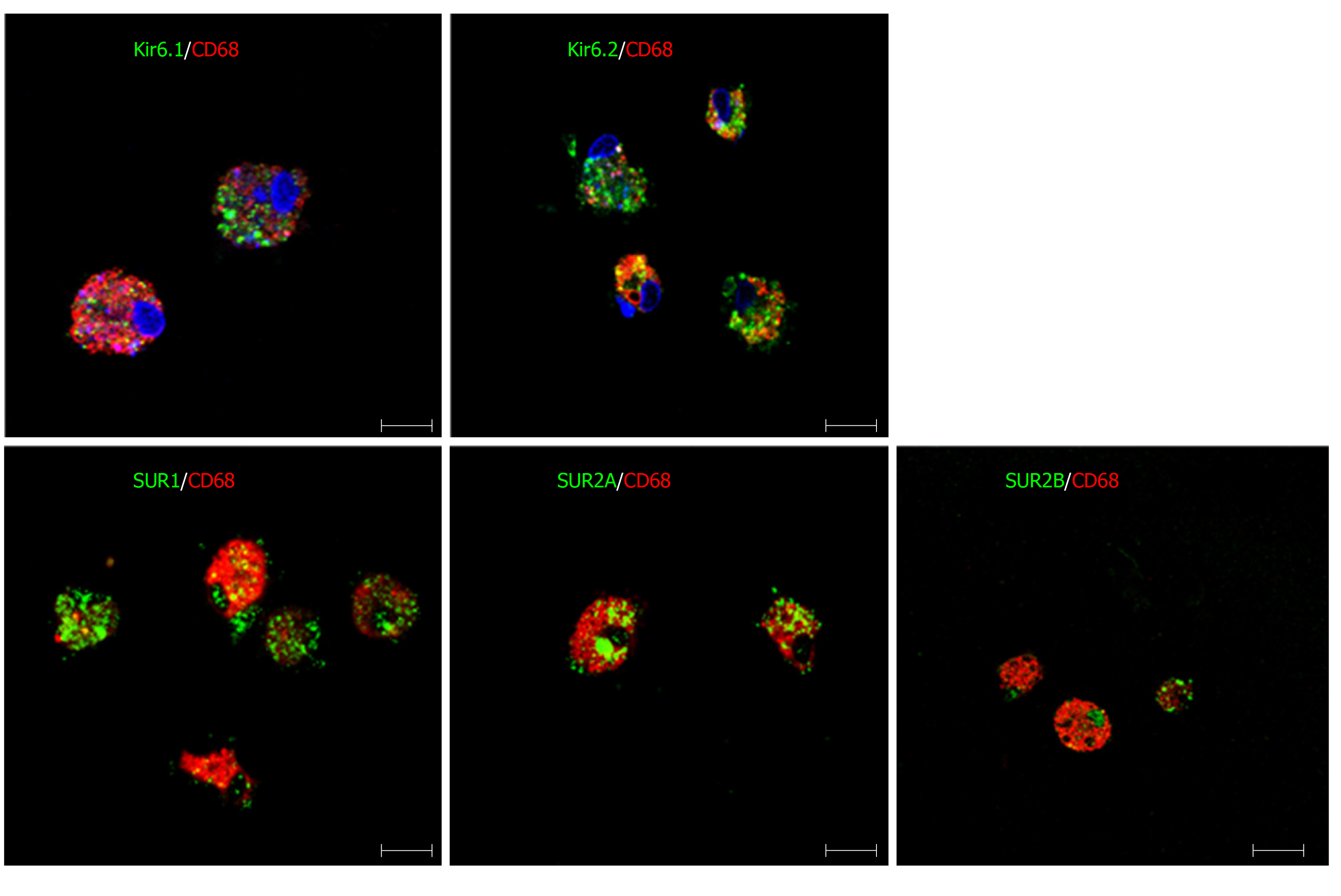

To show if pore-forming subunits are co-localized with regulatory subunits in rat liver, immunofluorescence double staining was performed. Positive immunoreactivity of Kir6.1 (Kir6.1+) and Kir6.2 (Kir6.2+) was detected as green fluorescence (Alexa488, Figures 7A, 7D, 8A, 8D, 9A and 9D), and that of SUR1 (SUR1+), SUR2A (SUR2A+) and SUR2B (SUR2B+) was detected as red fluorescence (Alexa594, Figures 7B, 7E, 8B, 8E, 9B, and 9E). In hepatocytes, Kir6.1+ and/or Kir6.2+ were hardly observed to be colocalized with SUR1+, SUR2A+, and/or SUR2B+. Instead, in a small number of round, oval, or spindle-shaped cells located beside the sinusoid, Kir6.1+ and/or Kir6.2+ cells were colocalized with that for SUR1, SUR2A, and/or SUR2B (Figures 7C, 7F, 8C, 8F, 9C, and 9F). When labeled by GFAP, a marker of HSCs, some of the Kir6.1+ and/or Kir6.2+ cells were colocalized with GFAP beside the sinusoid (Figure 10). GFAP+ cells also showed immunoreactivity to SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B in the sinusoidal lining (Figure 10). When labeled with CD68, a marker of Kupffer cells, a few CD68+ cells were colocalized with Kir6.1 and Kir6.2, and more of these small CD68+ cells were showed immunoreactivity to SUR1, SUR2A and SUR2B (Figure 11).

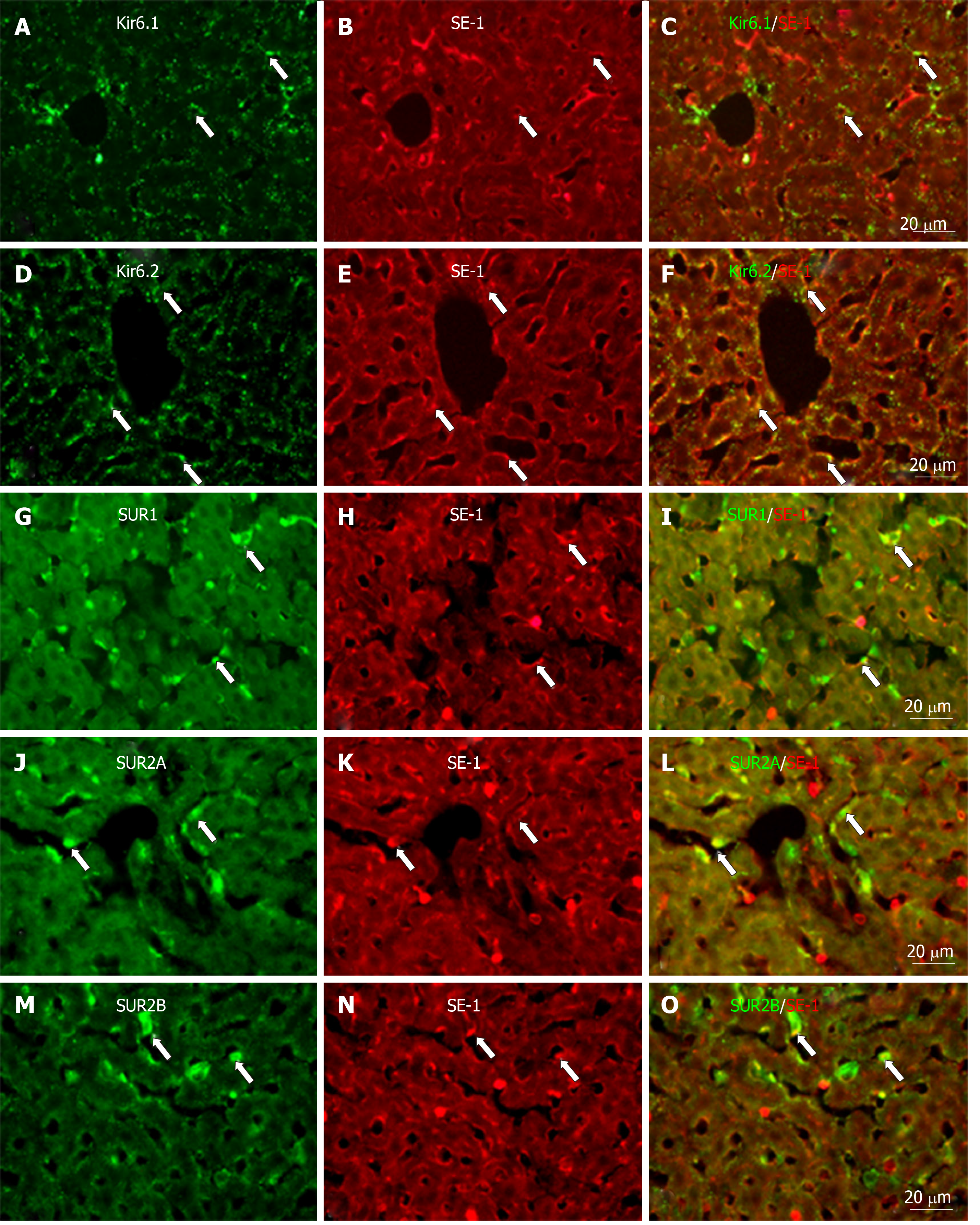

Similarly, when labeled with SE-1, a marker of SECs, a few SE-1+ cells colocalized with Kir6.1, SUR1, and SUR2B. On the other hand, a number of SE-1+ cells colocalized with Kir6.2 and SUR2A, respectively (Figure 12).

Primary HSCs were labeled with GFAP antibody. GFAP+ cells also showed positive immunoreactivity for Kir6.1 and/or Kir6.2 (Figure 13). This result indicated that the pore-forming subunits of the KATP channel were expressed in HSCs. In these HSCs, immunoreactivity for Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 were located in the peripheral cytoplasm, and that for GFAP was located in the perinuclear region. Colocalization of SURs and GFAP in primary HSCs has not been observed.

Primary Kupffer cells showed immunoreactivity for CD68, which confirmed them to be Kupffer cells. When incubating these cells with antibodies of KATP channel subunits, the CD68+ cells showed immunopositive reactivity for Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B (Figure 14).

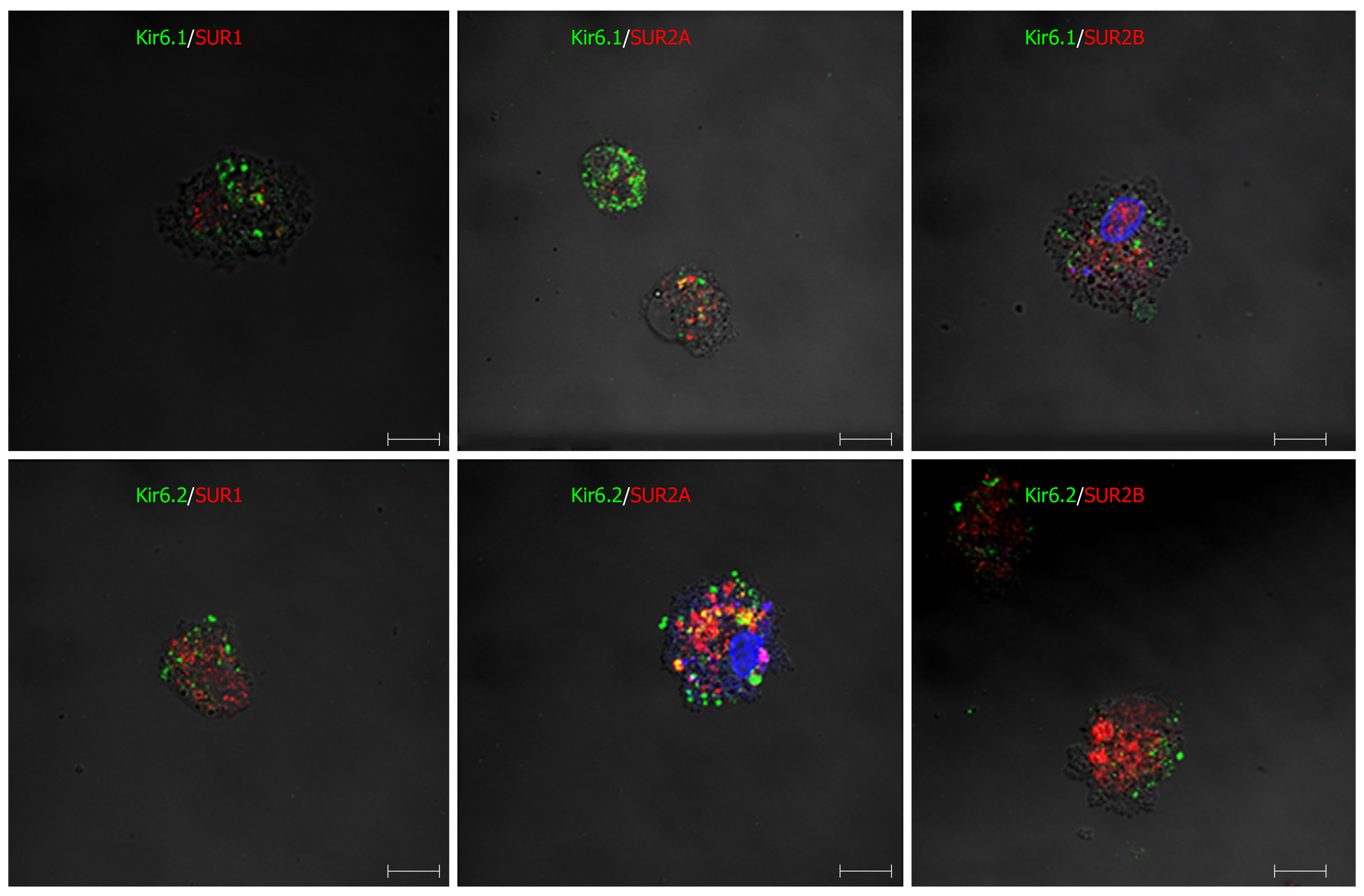

Furthermore, when primary Kupffer cells were incubated with multiple paired combined antibodies of pore-forming subunits and regulatory subunits, they showed immunoreactivity for Kir6.1/SUR1, Kir6.1/SUR2A, Kir6.1/SUR2B, Kir6.2/SUR1, Kir6.2/SUR2A, and Kir6.2/SUR2B (Figure 15). The immunoreactive products for KATP channel subunits exhibited a punctate or granular appearance.

In this study, a new polyclonal anti-SUR1 antibody was generated and applied to investigate the exhibition and localization of SUR1 in rat liver. Its specificity was assessed by preabsorption with an immunizing peptide antigen in western blot analysis (Figure 1B). The most significant band at 100 kDa disappeared in the presence of the immunizing antigen, showing the high specificity of the antiserum. The specificity of the antisera for SUR2A and SUR2B was demonstrated elsewhere[35]. The expression of five kinds of KATP channel subunits in rat liver extract was revealed by western blot analysis with the antibodies, including this new anti-SUR1, and every antibody revealed their corresponding band in the liver extract, respectively (Figure 1). This means that the rat liver contains five kinds of KATP channel subunits: Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B.

In liver sections, immunoreactivity for Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR2A and SUR2B was weakly to moderately expressed around the central vein and gradually decreased along the liver plate (Figures 2, 3, 5, and 6), but the immunoreactivity for SUR1 showed no such tendency (Figure 4). The Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 pore-forming subunits of the KATP channel were weakly expressed in hepatocytes and sinusoidal lining cells, such as HSCs, Kupffer cells, and SECs. Under high magnification, the Kir6.1 protein was detected as punctate immunoreactive products (Figure 2B) and the Kir6.2 protein was detected as granular immunoreactive products, indicating that Kir6.1 was located in the mitochondria and Kir6.2 in the endoplasmic reticulum, as shown in previous studies on rat brain[8,9]. The regulatory subunits SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B were mainly located in small cells, and exhibited staining in sinusoidal cells and weak staining in the cell membrane of hepatocytes.

The KATP channels play important roles in hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, ischemia and hypoxia[16,36]. Kir6.1 mRNA and protein are upregulated during myocardial infarction[17,37,38]. When the liver is in ischemia followed by reperfusion, hepatocytes around the central veins were more markedly degenerated than those in the peripheral zone of the liver lobule[38]. During liver ischemia, the different degenerated zonal areas are accordant with the liver blood supply being made up of different gradients of oxygen, hormones, and metabolites, as well as zonal differences form periportal to perivenous[39,40]. The similar zonal differences in immunoreactivity for Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR2A, and SUR2B might indicate that these subunits of KATP channels have some relationship with the protection of hepatocytes, though colocalization of these subunits was hardly observed in the sections of normal rat liver. KATP channels are important in liver regeneration for keeping a higher ATP content in liver tissue during partial hepatectomy[15] since, clinically, hepatocyte regeneration is a key point for partial liver transplantation.

It is well known that, in addition to parenchymal cells, the liver consists of three other kinds of cells, i.e. HSCs, Kupffer cells, and SECs[41]. HSCs are located between hepatocytes and SECs[31]. They store large amounts of vitamin A and produce extracellular matrix for liver fibrogenesis[31,41]. The pore-forming subunits (Kir6.1 and Kir6.2) were clearly colocalized in HSCs with GFAP both in liver sections and primary cells (Figures 10 and 13). Although the regulatory subunits (SURs) were not yet observed in primary HSCs, they were colocalized in HSCs with GFAP in liver sections (Figure 11). These results might indicate that the KATP channels have some relation to HSC matrix secretion and fibrogenesis.

In addition to the metabolism of glucose, lipids, hormones, and various substances, the liver also plays important roles in the immune response to eliminate pathogens, such as microorganisms, endotoxins, portal antigens, and tumor cells, and Kupffer cells are responsible for these crucial functions of host defense[42]. There are several subsets of Kupffer cells categorized by the cytokines they produce, such as CD11b+, CD68+, CD11b- and/or CD68-, CD32, and so on[40,43]. Kupffer cells can also be divided into two groups: bone marrow-derived macrophages and sessile hepatic macrophages. These different groups of Kupffer cells play different roles in the liver. For instance, when mice were given food with high-fat or high-cholesterol, CD68+ Kupffer cells decreased while CD11b+ Kupffer cells increased in number[40]. KATP channels exhibit different physiological and pharmacological functions depending on their subunit composition[26]. For example, Kir6.2 with SUR1 is strongly sensitive to the KATP channel activator diazoxide, but not to other activators such as pinacidil[25], while Kir6.2 with SUR2A is strongly sensitive to pinacidil and cromakalin but only weakly to diazoxide[26]. The diversity of subunit composition of KATP channels in Kupffer cells might correspond to different types of Kupffer cells or to their various functional stages.

In SECs, SE-1 immunopositive cells were colocalized in different numbers with the five kinds of KATP channel subunits, respectively (Figure 12). It is well known that SECs are highly specialized endothelial cells (with different classifying types) located between blood, hepatocytes and HSCs[31]. In the physiological state, SECs have a low proliferation rate. They maintain HSC quiescence, thus inhibiting intrahepatic vasoconstriction and fibrosis development under normal conditions. They are also differentially renewable under physiological and pathological conditions[44]. They are also involved in liver regeneration following acute liver injury and partial hepatectomy[45]. They play a key role in promoting liver regeneration by orchestrating the harmonious regeneration of the different cell types and renew themselves with asynchronous liver regeneration[44]. In the present study, SECs showed different combinations of Kir6.x and SURs, which indicates that they have multiple kinds of KATP channels corresponding with their multiple functions under physiological and pathological conditions.

The present study is, to our knowledge, the first report that HSCs, Kupffer cells, and SECs contain KATP channel subunits. Further investigation is needed to elucidate their functions in detail in liver metabolism, immunity, and fibrogenesis during liver injury.

ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels coupling nutrient metabolism to membrane potential are sensitive to intracellular ATP concentrations and ATP/ADP ratios. KATP channels are hetero-octameric in composition, formed by four pore-forming subunits including Kir6.1 and Kir6.2, which belong to the inward rectifying potassium channel family, and four regulatory subunits, SUR1, SUR2A and SUR2B, which belong to members of the ATP-binding cassette protein family. KATP channels were considered to be involved in cellular functions, such as pancreatic β cell secretion, muscle and neuronal excitability, and so on.

How KATP channels work in liver hepatocytes and sinusoidal cells is important to help understand liver function under normal and injury conditions. The first step is to characterize the localization and distribution of KATP channel subunits in different cells of the liver. This research focused on the localization and distribution of KATP channel subunits in hepatocytes and sinusoidal cells of rat liver. This research will provide the basic data to guide further research in medicine exploitation and clinical treatment for related liver diseases.

To investigate the expression of KATP channel subunits in rat liver and their localization in different cells of the liver.

In order to obtain basic knowledge of KATP channel subunits in rat liver distribution and localization, extracted liver protein was used for immunoblot analysis, cryosections of liver were used for immunohistochemistry, and primary cultured hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and Kupffer cells were used for immunocytochemistry.

In the present study, five types of KATP channel subunits, including Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, SUR2A and SUR2B, were expressed in rat liver as revealed by immunoblot analysis and immunohistochemistry. Double immunofluorescence staining of cryosections, primary cultured HSCs and Kupffer cells showed that not only hepatocytes, but also HSCs, Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) contain KATP channel subunits.

The present study revealed that KATP channel subunits are expressed in rat liver, which is the first report that HSCs, Kupffer cells, and SECs contain KATP channel subunits formed by Kir6.1/SUR1, Kir6.1/SUR2A, Kir6.1/SUR2B, Kir6.2/SUR1, Kir6.2/SUR2A, and Kir6.2/SUR2B. Different combinations of KATP channels have different physiological and pharmacological characteristics. Thus, this research will supply basic experimental data to guide further exploration of liver function under normal and injury conditions.

In the present study, all experiments were performed under normal conditions. Thus, further study is needed to elucidate changes in KATP channel subunit composition under different metabolic states, including ischemia and hypoxia in vitro and/or in vivo with the use of KATP channel openers and blockers, such as diazoxide, pinacidil, glibenclamide, and tolbutamide.

| 1. | Inagaki N, Inazawa J, Seino S. cDNA sequence, gene structure, and chromosomal localization of the human ATP-sensitive potassium channel, uKATP-1, gene (KCNJ8). Genomics. 1995;30:102-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aguilar-Bryan L, Clement JP 4th, Gonzalez G, Kunjilwar K, Babenko A, Bryan J. Toward understanding the assembly and structure of KATP channels. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:227-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ashcroft FM, Kakei M, Kelly RP. Rubidium and sodium permeability of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in single rat pancreatic beta-cells. J Physiol. 1989;408:413-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ashcroft SJ, Ashcroft FM. Properties and functions of ATP-sensitive K-channels. Cell Signal. 1990;2:197-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 533] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aizawa T, Asanuma N, Terauchi Y, Suzuki N, Komatsu M, Itoh N, Nakabayashi T, Hidaka H, Ohnota H, Yamauchi K, Yasuda K, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T, Hashizume K. Analysis of the pancreatic beta cell in the mouse with targeted disruption of the pancreatic beta cell-specific glucokinase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:460-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, Wang CZ, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Seino S. A family of sulfonylurea receptors determines the pharmacological properties of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:1011-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 724] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Akaike N, Jin YH, Koyama S. Functional interaction between Na(+)-K+ pump and KATP channels in the CNS neurons under experimental brain ischemia. Jpn J Physiol. 1997;47 Suppl 1:S50-S51. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Zhou M, Tanaka O, Sekiguchi M, Sakabe K, Anzai M, Izumida I, Inoue T, Kawahara K, Abe H. Localization of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit (Kir6. 1/uK(ATP)-1) in rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;74:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhou M, Tanaka O, Suzuki M, Sekiguchi M, Takata K, Kawahara K, Abe H. Localization of pore-forming subunit of the ATP-sensitive K(+)-channel, Kir6.2, in rat brain neurons and glial cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;101:23-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anzai N, Kawahara K, Sakai T, Komatsu Y, Inagaki N, Seino S. Localization of the inward rectifier subunit ukatp-1 (kir6.1) in adult rat kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:1275. |

| 11. | Kawahara K, Anzai N. Potassium transport and potassium channels in the kidney tubules. Jpn J Physiol. 1997;47:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou M, He HJ, Suzuki R, Tanaka O, Sekiguchi M, Yasuoka Y, Kawahara K, Itoh H, Abe H. Expression of ATP sensitive K+ channel subunit Kir6.1 in rat kidney. Eur J Histochem. 2007;51:43-51. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zhou M, He HJ, Tanaka O, Suzuki R, Sekiguchi M, Yasuoka Y, Kawahara K, Itoh H, Abe H. Localization of the sulphonylurea receptor subunits, SUR2A and SUR2B, in rat renal tubular epithelium. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;214:247-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Inagaki N, Tsuura Y, Namba N, Masuda K, Gonoi T, Horie M, Seino Y, Mizuta M, Seino S. Cloning and functional characterization of a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues, including pancreatic islets, pituitary, skeletal muscle, and heart. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5691-5694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nakagawa Y, Yoshioka M, Abe Y, Uchinami H, Ohba T, Ono K, Yamamoto Y. Enhancement of liver regeneration by adenosine triphosphate-sensitive K⁺ channel opener (diazoxide) after partial hepatectomy. Transplantation. 2012;93:1094-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yokota R, Tanaka M, Yamasaki K, Araki M, Miyamae M, Maeda T, Koga K, Yabuuchi Y, Sasayama S. Blockade of ATP-sensitive K+ channels attenuates preconditioning effect on myocardial metabolism in swine: myocardial metabolism and ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Int J Cardiol. 1998;67:225-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Akao M, Otani H, Horie M, Takano M, Kuniyasu A, Nakayama H, Kouchi I, Murakami T, Sasayama S. Myocardial ischemia induces differential regulation of KATP channel gene expression in rat hearts. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3053-3059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yokoshiki H, Sunagawa M, Seki T, Sperelakis N. ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic, cardiac, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C25-C37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP 4th, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1279] [Cited by in RCA: 1236] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aguilar-Bryan L, Clement JP 4th, Nelson DA. Sulfonylurea receptors and ATP-sensitive potassium ion channels. Methods Enzymol. 1998;292:732-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Molecular biology of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:101-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Babenko AP, Gonzalez GC, Bryan J. Hetero-concatemeric KIR6.X4/SUR14 channels display distinct conductivities but uniform ATP inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31563-31566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Inagaki N, Seino S. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: structures, functions, and pathophysiology. Jpn J Physiol. 1998;48:397-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shyng S, Nichols CG. Octameric stoichiometry of the KATP channel complex. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:655-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bryan J, Vila-Carriles WH, Zhao G, Babenko AP, Aguilar-Bryan L. Toward linking structure with function in ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Diabetes. 2004;53 Suppl 3:S104-S112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Seino S, Miki T. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;81:133-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tricarico D, Mele A, Lundquist AL, Desai RR, George AL, Conte Camerino D. Hybrid assemblies of ATP-sensitive K+ channels determine their muscle-type-dependent biophysical and pharmacological properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1118-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pocai A, Lam TK, Gutierrez-Juarez R, Obici S, Schwartz GJ, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L, Rossetti L. Hypothalamic K(ATP) channels control hepatic glucose production. Nature. 2005;434:1026-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 29. | Malhi H, Irani AN, Rajvanshi P, Suadicani SO, Spray DC, McDonald TV, Gupta S. KATP channels regulate mitogenically induced proliferation in primary rat hepatocytes and human liver cell lines. Implications for liver growth control and potential therapeutic targeting. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26050-26057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shiratori Y, Imazeki F, Moriyama M, Yano M, Arakawa Y, Yokosuka O, Kuroki T, Nishiguchi S, Sata M, Yamada G, Fujiyama S, Yoshida H, Omata M. Histologic improvement of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C who have sustained response to interferon therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:517-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 547] [Cited by in RCA: 541] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Mezaki Y, Yamaguchi N, Yoshikawa K, Miura M, Imai K, Itoh H, Senoo H. Insoluble, speckled cytosolic distribution of retinoic acid receptor alpha protein as a marker of hepatic stellate cell activation in vitro. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:687-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Troeger JS, Mederacke I, Gwak GY, Dapito DH, Mu X, Hsu CC, Pradere JP, Friedman RA, Schwabe RF. Deactivation of hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis resolution in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1073-83.e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stewart RK, Dangi A, Huang C, Murase N, Kimura S, Stolz DB, Wilson GC, Lentsch AB, Gandhi CR. A novel mouse model of depletion of stellate cells clarifies their role in ischemia/reperfusion- and endotoxin-induced acute liver injury. J Hepatol. 2014;60:298-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Alpini G, Phillips JO, Vroman B, LaRusso NF. Recent advances in the isolation of liver cells. Hepatology. 1994;20:494-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhou M, He HJ, Tanaka O, Sekiguchi M, Kawahara K, Abe H. Localization of the ATP-sensitive K(+) channel regulatory subunits SUR2A and SUR2B in the rat brain. Neurosci Res. 2012;74:91-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Seino S. Physiology and pathophysiology of K(ATP) channels in the pancreas and cardiovascular system: a review. J Diabetes Complications. 2003;17:2-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Akao M, Sakurai T, Horie M, Otani H, Takano M, Kouchi I, Murakami T, Sasayama S. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade abolishes specific K(ATP)channel gene expression in rats with myocardial ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2239-2247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Oktar GL, Demir Amac N, Elmas C, Arslan M, Goktas G, Iriz E, Erer D, Zor MH, Tatar T. The histopathological effects of levosimendan on liver injury induced by myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2015;116:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Dombrowski F, Evert M. Revelation of simple and complex liver acini after portal transplantation of pancreatic islets or thyroid follicles in rats. Hepatology. 2007;45:705-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Katz NR. Metabolic heterogeneity of hepatocytes across the liver acinus. J Nutr. 1992;122:843-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Schieferdecker HL, Schlaf G, Jungermann K, Götze O. Functions of anaphylatoxin C5a in rat liver: direct and indirect actions on nonparenchymal and parenchymal cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:469-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ikarashi M, Nakashima H, Kinoshita M, Sato A, Nakashima M, Miyazaki H, Nishiyama K, Yamamoto J, Seki S. Distinct development and functions of resident and recruited liver Kupffer cells/macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1325-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kinoshita M, Uchida T, Sato A, Nakashima M, Nakashima H, Shono S, Habu Y, Miyazaki H, Hiroi S, Seki S. Characterization of two F4/80-positive Kupffer cell subsets by their function and phenotype in mice. J Hepatol. 2010;53:903-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Poisson J, Lemoinne S, Boulanger C, Durand F, Moreau R, Valla D, Rautou PE. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells: Physiology and role in liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66:212-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 761] [Article Influence: 84.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Ping C, Xiaoling D, Jin Z, Jiahong D, Jiming D, Lin Z. Hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells promote hepatocyte proliferation early after partial hepatectomy in rats. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:576-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gencdal G S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Ma YJ