Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.106027

Revised: April 9, 2025

Accepted: May 26, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 288 Days and 4.8 Hours

In critical care practice, difficult airway management poses a substantial chal

To review the local experience of using ECMO support in patients with difficult airway management.

This retrospective case series study includes patients with difficult airway management who required ECMO support at a tertiary hospital in a Middle Eastern country.

Between 2016 and 2023, a total of 13 patients required ECMO support due to challenging airway patency in the operating room. Indications for ECMO encompassed various diagnoses, including tracheal stenosis, external tracheal compression, and subglottic stenosis. Surgical interventions such as tracheal resection and anastomosis often necessitated ECMO support to maintain adequate oxygenation and hemodynamic stability. The duration of ECMO support ranged from standby mode (ECMO implantation is readily available) to several days, with relatively infrequent complications observed. Despite the challenges encountered, most patients survived hospital discharge, highlighting the effectiveness of ECMO in managing difficult airways.

This study underscores the crucial role of ECMO as a life-saving intervention in selected cases of difficult airway management. Further research is warranted to refine the understanding of optimal management strategies and improve outcomes in this challenging patient population.

Core Tip: Veno-venous Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV ECMO) is occasionally used in airway obstruction, but the literature remains limited. Difficult airway management can be fatal without advanced support strategies. Complex and deformed airways can challenge even the most experienced anesthesiologist. Current approaches and techniques for such patients may be inadequate. VV ECMO can be a bridge to definitive airway establishment and surgical intervention. VV ECMO can be safely and effectively instigated during the perioperative period and can avoid mishaps in difficult and failed intubation scenarios. Multidisciplinary team engagement and meticulous planning are key to the successful management of cases with difficult airways.

- Citation: Eltahir M, Fawzy I, Ibrahim AS, Ibrahim EA, Mazhar R, Shallik NAE, El-Menyar A, Shehatta AL. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in patients with difficult airway management: Case series of 13 patients. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(4): 106027

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i4/106027.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i4.106027

Difficult airway management refers to conditions where an experienced anesthesiologist struggles to maintain adequate oxygenation and ventilation using standard techniques[1]. Central airway obstruction due to neck or thoracic lesions or tumors is a particularly perilous emergency with high mortality[2]. Traditional airway management techniques, such as nasal oxygen, face mask, bag-valve-mask ventilation, fiberoptic endoscopy, endotracheal intubation, and surgical airway, may be ineffective in managing severe and anatomically complex airway obstruction. Failure to secure a patent airway results in hypoxia, hypercapnia, and cardiorespiratory collapse and may lead to cardiac arrest and severe neurological damage. Unfortunately, a paucity of literature addresses effective management strategies for this life-threatening condition[3].

Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV ECMO) provides temporary respiratory support using venous drainage, oxygenation, and decarboxylation and pumping well-oxygenated blood back to the patient, and it has been used successfully in patients with severe respiratory failure due to acute respiratory distress syndrome, trauma, and sepsis[4]. There is limited evidence on the safety and efficacy of ECMO in patients with central airway obstruction. Few case reports have described the successful use of ECMO in patients with airway obstruction due to tracheal tumors, laryngeal edema, and trauma[5-9]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of case reports and case series concluded that ECMO could be a viable option in patients with difficult airway management. However, further studies are needed to evaluate its efficacy and safety[10]. Herein, we describe our experience with 13 patients with difficult airway management who were referred for ECMO support. ECMO was proposed as a protective first-line strategy in difficult airway cases until a definitive surgical intervention was performed. We aim to explore the potential benefits and risks of this complex and invasive intervention to help refine the indications for ECMO use in this setting.

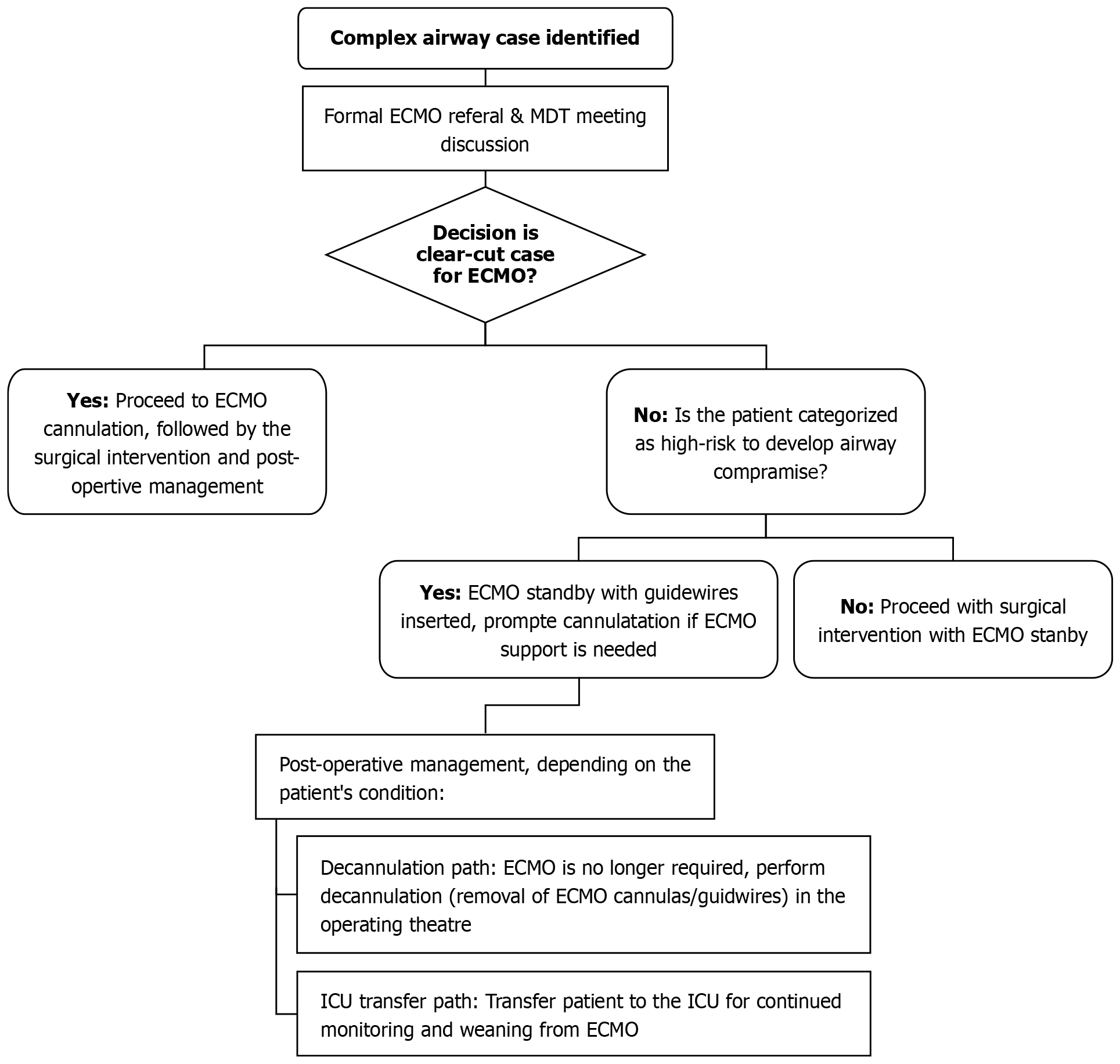

A retrospective analysis was conducted after obtaining institutional review board approval (MRC-04-24-385) at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC). All documented cases with ECMO application for difficult airway procedures between 2016 and 2023 were reviewed and analyzed. Data were retrieved from the electronic medical record and operative documentation at HMC, Qatar. Collected data included patients’ demographics, comorbidity, diagnosis, and management. Figure 1 summarizes the process of using ECMO support for complex airway procedures at HMC.

A total of 13 cases (8 females and five males) were identified. The most common reasons for ECMO consultation were tracheal stenosis (six patients) and subglottic stenosis (three patients). VV ECMO support was fully deployed in seven cases. ECMO support and team were readily available with or without inserting guidewires in the femoral veins for the rest of the cases (n = 6). The duration of ECMO support ranged between 45 min and 16 days. The patient who required the prolonged ECMO run (23 days) is the only mortality in this series. Otherwise, only one patient sustained cardiac arrest and was successfully resuscitated. The patient who required the longest ECMO support unfortunately did not survive. During management, he remained on VV ECMO for 16 days. In later stages, 21 days after decannulation from ECMO, his clinical status deteriorated, for which escalation to VA ECMO or additional right ventricular support was considered. However, given the patient's underlying diagnosis of advanced metastatic cancer with significant vascular and airway compression and worsening hemodynamic status despite maximal supportive measures, VA ECMO was deemed unlikely to provide additional benefit. The multidisciplinary team concluded that further escalation would not change the overall prognosis.

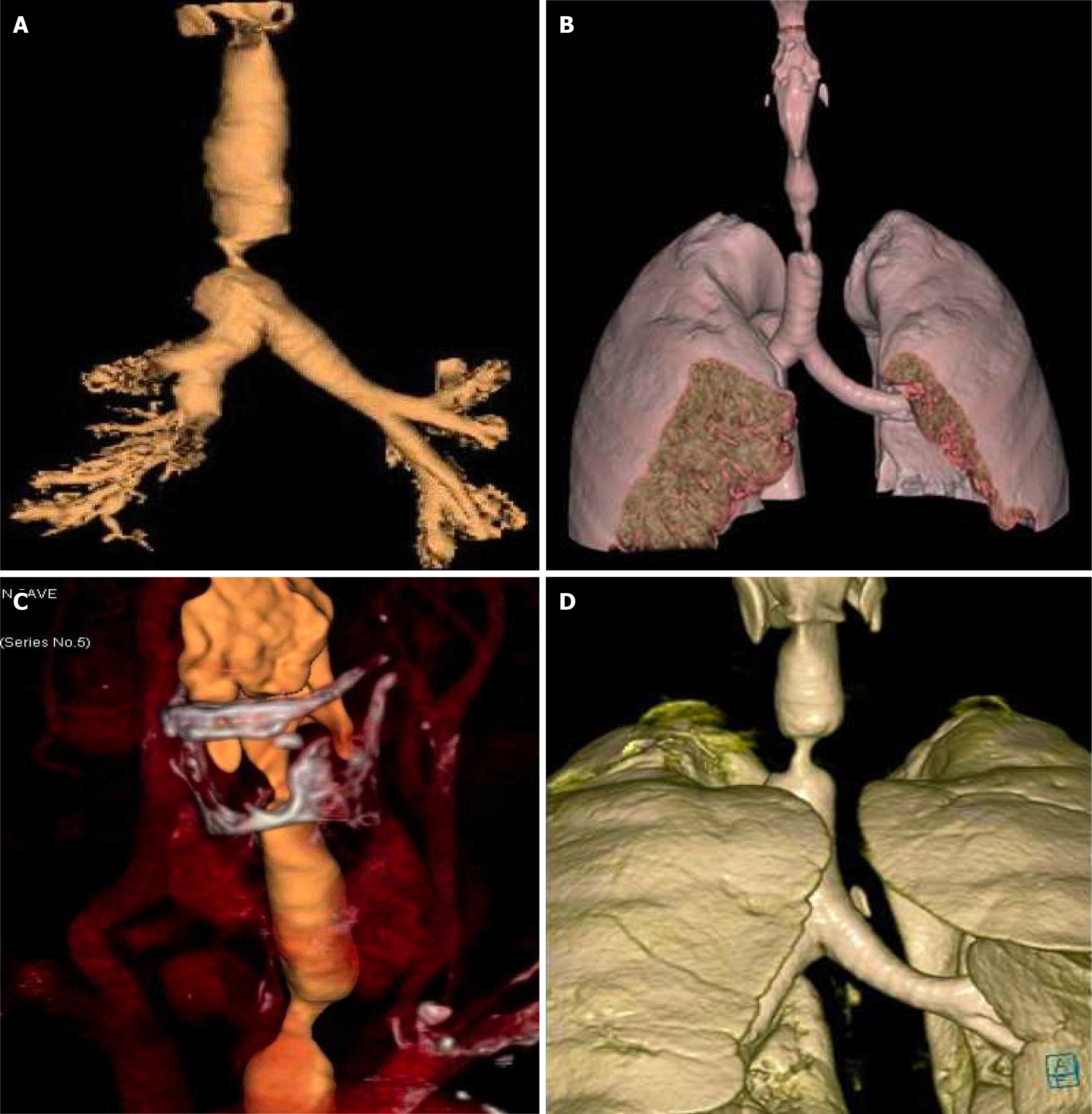

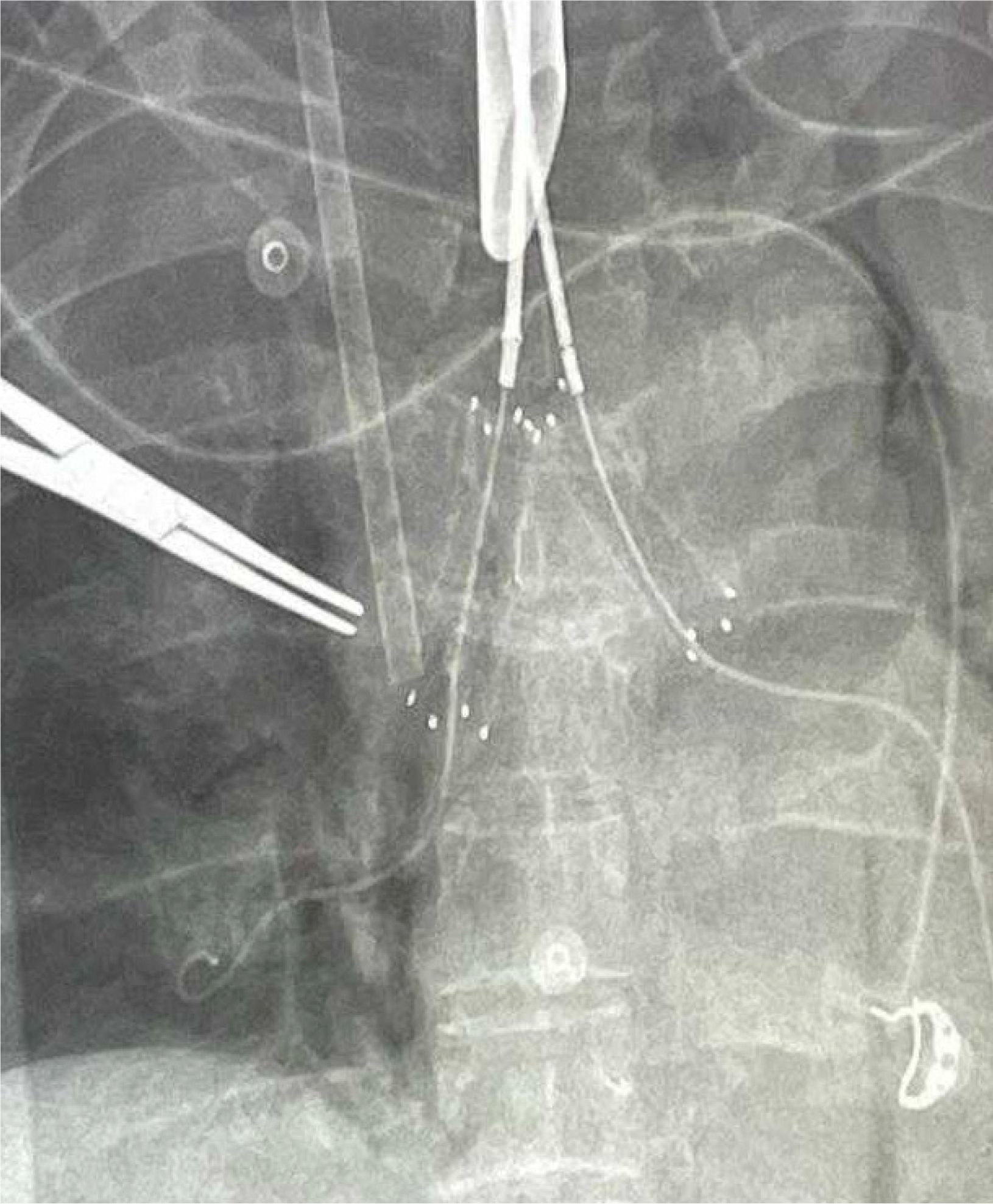

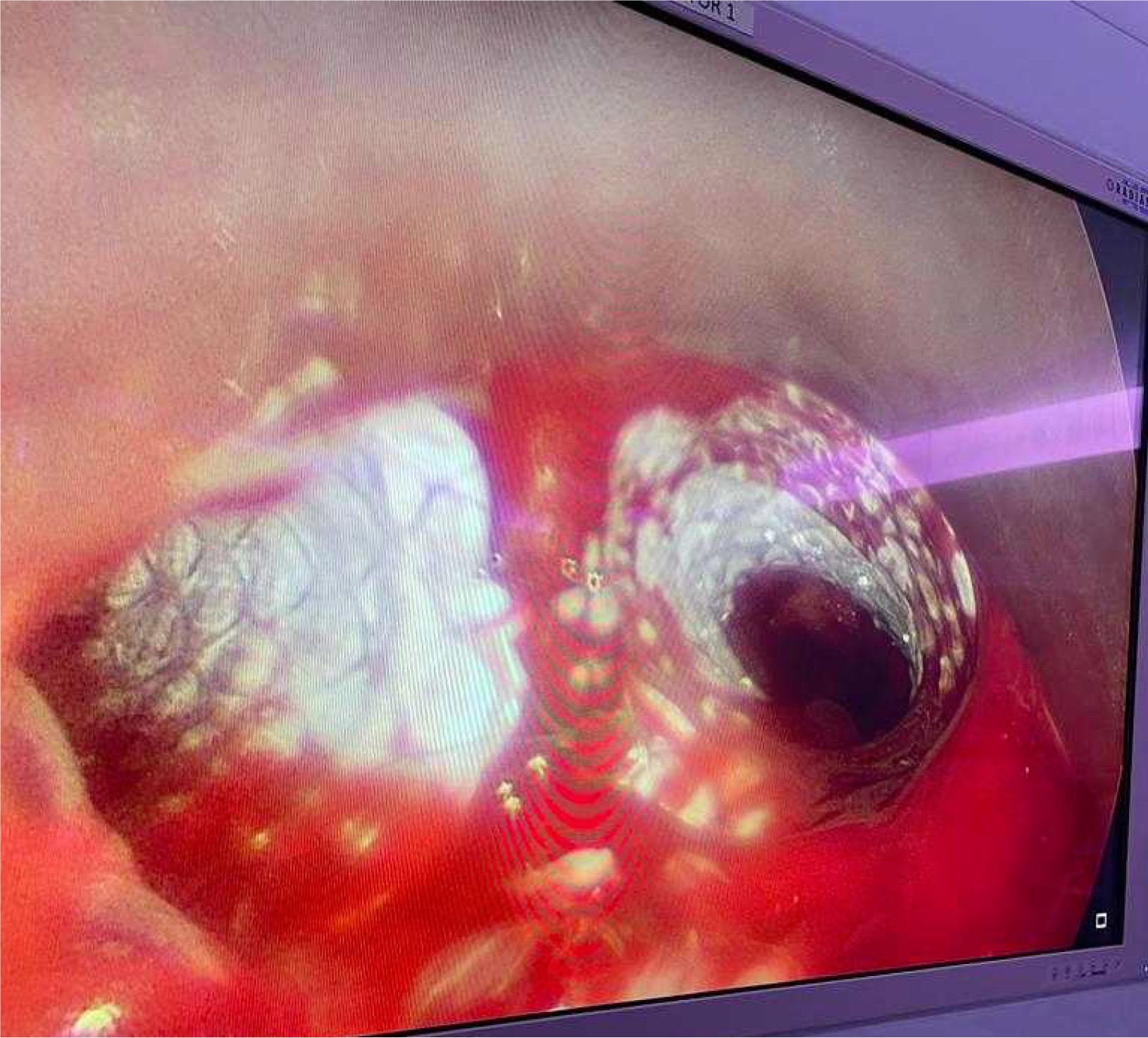

No systemic anticoagulation was administered in the perioperative period, and we did not observe any issues with circuit clotting or ECMO membrane dysfunction. Only one patient developed tension pneumothorax whilst on ECMO, which was unrelated to ECMO. This complication was unrelated to ECMO itself. The cause was tracheal perforation during intubation due to the sharp end of a Tribute endotracheal tube stylet in a patient with severe tracheal stenosis. The situation was recognized promptly and managed appropriately. We did not observe ECMO-related complications. Table 1 summarizes the patients’ data, including demographics, diagnosis, computed tomography (CT) findings, surgical and ECMO procedures, and outcomes. Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 are examples of airway difficulties in our cohort (Fluoroscopy X-ray, CT scan, and bronchoscopy imaging). Pain and nutritional management were integral parts of patient care. Pain control was achieved using multimodal analgesia, including opioids and sedatives tailored to each patient's needs. Nutritional support was initiated early, with a preference for enteral feeding; parenteral nutrition was used when enteral access was not feasible or contraindicated.

| Patient | Age | Gender | Morbidity | Diagnosis | CT findings | Type of ECMO | ECMO duration | Surgical intervention | Complications on ECMO | 90 days outcome |

| 1 | 29 | Male | Non | T- lymphoblastic leukemia | Near-total tracheal obstruction | ECMO team standby | 0 days | Non, intubated and underwent chemotherapy | N/A | Alive |

| 2 | 54 | Male | HTN, CAD | Post COVID intubation subglottic stenosis | Subglottic tracheal stenosis | ECMO standby guidewires inserted | 0 days | Tracheal resection with end-to-end anastomosis | N/A | Alive |

| 3 | 44 | Male | Non | Recurrent follicular thyroid cancer | External tracheal compression | ECMO team standby | 0 days | Tumor excision + neck dissection and sternectomy with reconstruction | N/A | Alive |

| 4 | 64 | Female | HTN, DM | Post COVID intubation subglottic stenosis | Fibrous band at the level of second tracheal ring | ECMO team Standby | 0 days | Excision and balloon dilatation | N/A | Alive |

| 5 | 37 | Female | HTN, DM, CKD | Tracheal stenosis post prolonged intubation | 50% subglottic stenosis | ECMO team standby | 0 days | Tracheal dilation | N/A | Alive |

| 6 | 68 | Female | HTN, CAD | Tracheal tumor | Mediastinal tumor infiltrating into the distal trachea and bronchi, bilaterally | VV ECMO | 5 days | Tumor debulking and bilateral bronchial/tracheal stenting | N/A | Alive |

| 7 | 70 | Female | HTN | Post COVID intubation tracheal stenosis | Tracheal stenosis | ECMO team standby | 5 days | Tracheal dilation + stenting | N/A | Alive |

| 8 | 50 | Female | Non | Tracheal stenosis post COVID-19 | Long segment of subglottic tracheal stenosis | VV ECMO | 45 minutes | Tracheal dilation + stenting | N/A | Alive |

| 9 | 50 | Male | Non | Tracheal stenosis post COVID-19 | Tracheal stenosis | VV ECMO | 2 days | Tracheal resection and anastomosis | N/A | Alive |

| 10 | 28 | Female | Non | Thyroid cancer with pulmonary metastasis | External tracheal compression | VV ECMO | 11 days | Endobronchial lesion removal and stenting | N/A | Alive |

| 11 | 44 | Male | Non | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Mediastinal mass causing near-total tracheal obstruction | ECMO team Standby | 0 days | Non, intubated and underwent chemotherapy | N/A | Alive |

| 12 | 28 | Female | CKD, lung cancer | Metastatic lung adenocarcinoma | Large intra tracheal tumor expanding over 80% of the lumen | VV ECMO | 16 days | Failed balloon dilatation and stenting, underwent. Radiotherapy | N/A | Died 21 days after ECMO decannulation |

| 13 | 29 | Male | Non | Post traumatic airway injury stenosis | Tracheal stenosis with surrounding soft tissue component | VV ECMO | 10 days | Tracheal dilatation and stenting | Tension pneumothorax cardiac arrest | Alive |

| 4 months later the patient developed SOB and strider | Tracheal stent in situ with distal stenosis | Narrowing below the lower end of the stents about 8 mm in diameter | No ECMO was available | 0 | Flexible + rigid bronchoscopy, extraction of tracheal stent, +- replacement with shorter stent +- thoracotomy and tracheal repair | N/A | Failed ventilation and died on the theatre table | |||

This case series demonstrates that VV ECMO support can add further safety to airway management and facilitate challenging surgery. In our cases, VV ECMO support was feasible and did not pose additional risk to the patients. Difficult airway management poses significant challenges in anesthetics and critical care practice, requiring advanced techniques and interventions to ensure patient safety and better outcomes. Asphyxia and respiratory failure are the main causes of death in patients with airways oppressed by adjacent tumors[10]. Stent placement has become a common minimally invasive intervention for airway obstruction caused by tumors[10]. In patients with severe airway obstruction due to neck and chest tumors, stent placement poses significant risks. These risks include complete airway obstruction due to inadequate ventilation and severe bleeding caused by stent contact with highly vascular tumors[10]. Although stent placement can provide temporary relief, surgical intervention remains the most effective long-term treatment for these patients. Additionally, stents can migrate or fracture, leading to potential complications[7,11,12].

ECMO has shown promise in supporting patients with critical airway obstruction during stent placement[7]. ECMO can buy time to plan and implement adequate treatment, thereby minimizing procedure-related complications. Further

In this case series, we observed a broad range of presentations and management strategies. The demographics of the patient cohort reflect a diversity of age groups and comorbidities, highlighting the complexity of cases encountered in clinical practice. Notably, most patients were females, not males. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were prevalent comorbidities among the cohort. Surgery was the most effective treatment for all cases subjected to surgical procedures.

No formal guidelines or algorithm is currently available to help clinical teams decide on ECMO deployment for complex airway or thoracic procedures except for the American Society of Anesthesiologists 2022 Guidelines[14]. The latter recommends initiating ECMO when considered appropriate and available. The authors admit a lack of conclusive evidence despite their recommendations. Notably, the guideline does not suggest early or elective ECMO but rather an emergency implantation in adult and pediatric populations. This may be a less favorable strategy in anticipated and known difficult airways as time constraints, worsening hypoxia, cardiovascular instability secondary to severe hypoxia, and hypercarbia, in addition to the time needed to establish ECMO flow, make favorable neurological outcomes less likely. In our institution, ECMO for such cases is offered following a thorough multidisciplinary review, where there is a consensus that the proposed procedure or airway poses significant risk and conventional airway management is deemed inadequate, is associated with high risk, or is unlikely to be successful. The current model at HMC starts with a formal referral for ECMO support ahead of complex thoracic or airway procedures, followed by a review by the ECMO team. A multidisciplinary team meeting is held to formulate the proposed management plan in the operating theatre. Informed consent is obtained (or emergency consent is required in case of an uncooperative or unconscious patient), and a full explanation is provided to the patient. In cases that are considered clear-cut, bifemoral venous cannulation is performed, and ECMO flow is established, followed by definitive airway management and surgical intervention. In high-risk patients, guidewires are inserted under aseptic techniques and ultrasound guidance in both common femoral veins. Both guidewires are kept in situ under complete aseptic conditions for the entire duration of surgery. This facilitates quick cannulation for ECMO when required and minimizes the risk of significant hypoxia. At the end of the procedure, depending on continuing assessment and multidisciplinary input, guidewires are removed, or decannulation of ECMO in the operating theatre upon completion of the procedure, or the patient is transferred to intensive care unit with full ECMO support pending improvement and/or stabilization.

In this cohort, the indications for ECMO varied among our patients, with tracheal stenosis and external tracheal compression being the most common diagnoses. Tracheal stenosis, whether due to traumatic injury, neoplastic ob

The duration of ECMO support varied widely among our patients, ranging from standby mode (ECMO team and equipment readily available in the OR without ECMO cannulation) up to 16 days of full ECMO support. ECMO provides a vital bridge to ensure adequate oxygenation and hemodynamic stability throughout the procedure for patients un

Complications associated with ECMO therapy were infrequent in our cohort, with only one patient experiencing cardiac arrest during ECMO support. Despite the inherent risks associated with ECMO, most of our patients survived discharge, highlighting the effectiveness of this advanced support modality in managing difficult airways. Notably, one patient in the present study died (perioperative ECMO support was temporarily unavailable during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic). This could underscore the importance of patient selection and prognostic assessment in decision-making as resource management of ECMO during the crisis and pandemic is critical[15,16]. Factors such as the presence of advanced malignancies may portend a poorer prognosis despite aggressive interventions and careful consideration of goals of care and end-of-life planning before considering ECMO. In the present study, recirculation (the drainage cannula withdraws reinfused oxygenated blood without passing through the systemic circulation)[17] was actively considered throughout patient management. Venous cannula placement was optimized, and flow dynamics were monitored closely. No signs of significant recirculation were suspected in our cases.

This study has some limitations, which may limit the generalizability of findings, as practice patterns may differ in other institutions. The retrospective nature, few procedures, and small sample size warrant careful interpretation of the results.

VV ECMO support can be a life-saving intervention for patients experiencing severe airway compromise. ECMO deployment as a bridge to surgical intervention can facilitate complex thoracic surgical procedures and provide the surgical team with optimum peri-procedural conditions. This report highlights the process of the “unconventional” ECMO application for surgical procedures at HMC. Our retrospective analysis provides insights into the management of difficult airways with ECMO support. Despite the complexity of the cases encountered, ECMO emerged as a crucial adjunct in facilitating airway stabilization and supporting patients through complex surgical interventions and critical illness. Continued refinements in ECMO technology and multidisciplinary collaboration are essential in further improving outcomes for patients with challenging airway pathology.

| 1. | Kollmeier BR, Boyette LC, Beecham GB, Desai NM, Khetarpal S. Difficult Airway. 2023 Apr 10. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Cervantes A, Chirivella I. Oncological emergencies. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:iv299-iv306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liang L, Su S, He Y, Peng Y, Xu S, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Yu H. Early extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as bridge for central airway obstruction patients caused by neck and chest tumors to emergency surgery. Sci Rep. 2023;13:3749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, Demoule A, Lavoué S, Guervilly C, Da Silva D, Zafrani L, Tirot P, Veber B, Maury E, Levy B, Cohen Y, Richard C, Kalfon P, Bouadma L, Mehdaoui H, Beduneau G, Lebreton G, Brochard L, Ferguson ND, Fan E, Slutsky AS, Brodie D, Mercat A; EOLIA Trial Group, REVA, and ECMONet. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965-1975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1417] [Cited by in RCA: 1586] [Article Influence: 198.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stokes JW, Katsis JM, Gannon WD, Rice TW, Lentz RJ, Rickman OB, Avasarala SK, Benson C, Bacchetta M, Maldonado F. Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation during high-risk airway interventions. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021;33:913-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bozer J, Vess A, Pineda P, Essandoh M, Whitson BA, Seim N, Bhandary S, Awad H. Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for a Difficult Airway Situation-A Recommendation for Updating the American Society of Anesthesiologists' 'Difficult Airway Algorithm'. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2023;37:2646-2656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yunoki K, Miyawaki I, Yamazaki K, Mima H. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation-Assisted Airway Management for Difficult Airways. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:2721-2725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Grant BM, Ferguson DH, Aziz JE, Aziz SM. Successful use of VV ECMO in managing negative pressure pulmonary edema. J Card Surg. 2020;35:930-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fan Z, Zhu S, Chen J, Wen J, Li B, Liao X. The application of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in emergent airway management - a single-center retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2024;19:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malpas G, Hung O, Gilchrist A, Wong C, Kent B, Hirsch GM, Hart RD. The use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the anticipated difficult airway: a case report and systematic review. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65:685-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bi Y, Chen H, Li J, Fu P, Ren J, Han X, Wu G. Fluoroscopy-guided removal of individualised airway-covered stents for airway fistulas. Clin Radiol. 2018;73:832e1-832e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang Y, Luo M, Wang B, Qin Z, Zhou R. Perioperative, protective use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in complex thoracic surgery. Perfusion. 2022;37:590-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hong Y, Jo KW, Lyu J, Huh JW, Hong SB, Jung SH, Kim JH, Choi CM. Use of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in central airway obstruction to facilitate interventions leading to definitive airway security. J Crit Care. 2013;28:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, Abdelmalak BB, Agarkar M, Dutton RP, Fiadjoe JE, Greif R, Klock PA, Mercier D, Myatra SN, O'Sullivan EP, Rosenblatt WH, Sorbello M, Tung A. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2022;136:31-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 177.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Agerstrand C, Dubois R, Takeda K, Uriel N, Lemaitre P, Fried J, Masoumi A, Cheung EW, Kaku Y, Witer L, Liou P, Gerall C, Klein-Cloud R, Abrams D, Cunningham J, Madahar P, Parekh M, Short B, Yip NH, Serra A, Beck J, Brewer M, Fung K, Mullin D, Oommen R, Stanifer BP, Middlesworth W, Sonett J, Brodie D. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Coronavirus Disease 2019: Crisis Standards of Care. ASAIO J. 2021;67:245-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rabie AA, Elhazmi A, Azzam MH, Abdelbary A, Labib A, Combes A, Zakhary B, MacLaren G, Barbaro RP, Peek GJ, Antonini MV, Shekar K, Al-Fares A, Oza P, Mehta Y, Alfoudri H, Ramanathan K, Ogino M, Raman L, Paden M, Brodie D, Bartlett R. Expert consensus statement on venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation ECMO for COVID-19 severe ARDS: an international Delphi study. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Abrams D, Bacchetta M, Brodie D. Recirculation in venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2015;61:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/