Peer-review started: April 28, 2021

First decision: July 8, 2021

Revised: August 5, 2021

Accepted: December 22, 2021

Article in press: December 22, 2021

Published online: January 24, 2022

Processing time: 267 Days and 11.8 Hours

Co-stimulatory molecules are key mediators in the regulation of immune responses and knowledge of its different families, structure, and functions has improved in recent decades. Understanding the role of co-stimulatory molecules in pathological processes has allowed the development of strategies to modulate cellular functions. Currently, modulation of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules has been applied in clinical applications as therapeutic targets in diseases and promising results have been achieved.

Core Tip: Several reviews of co-stimulatory molecules have been published, however, this review summarizes the historical aspects, the cellular and molecular mechanisms of the different families of costimulatory molecules implied in processes of health and disease. All of this knowledge has been applied to develop different drugs targeting costimulatory molecules in different diseases like cancer and autoimmune diseases.

- Citation: Velazquez-Soto H, Real F, Jiménez-Martínez MC. Historical evolution, overview, and therapeutic manipulation of co-stimulatory molecules. World J Immunol 2022; 12(1): 1-8

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2824/full/v12/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5411/wji.v12.i1.1

Regulation of the immune response is a crucial process in the initiation and control of inflammatory phenomena. Various mechanisms capable of regulating T cell activation have been described. Co-stimulatory molecules were initially described as accessory signals present in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that interacted with T cells during the immunological synapse[1]. They comprise a diversity of glycoproteins expressed in the membrane of APCs, and they interact with other glycoproteins that function as their receptors on T cells, modulating in a positive or negative way the activation, proliferation, differentiation, and function of T cells[2]. In recent decades, advances in the knowledge of co-stimulatory molecules and the development of biological drugs allowed a therapeutical targeting of co-stimulatory molecules in distinct diseases[3].

A two-signal model of T cell activation was first proposed in the second half of the 1960s. The two signals were antigen recognition by an antigen receptor and the interaction with co-stimulatory molecules. Although the mechanisms were not known, the model proposed that in the absence of a second signal or "co-stimulation," the T cell would enter a state of paralysis or inactivation[4,5]. By the second half of the 1980s, a series of investigations had experimentally demonstrated the existence of co-stimulatory molecules and their participation in T cell activation[6-9]. The findings resulted in the description of a diversity of molecules and the investigation of their function in different disease models, which led to therapeutic applications. One example is the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, awarded to Tsuku Honjo and James P Alisson, for their contributions to the discovery of cytotoxic T lym

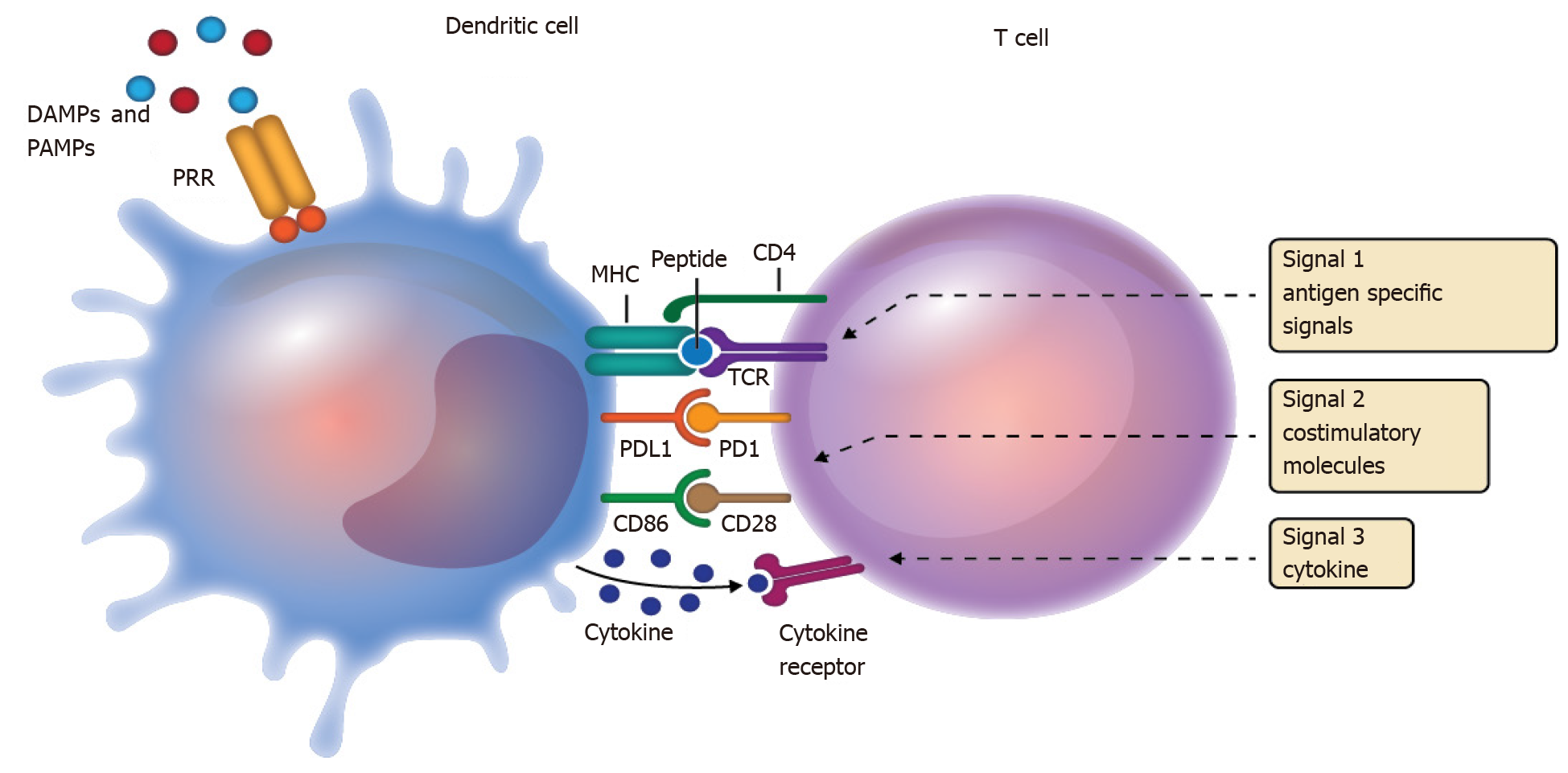

APCs are part of the innate immune system and act as an interface between antigen recognition and the adaptive response of T cells during antigen presentation[3]. Activation of T cells requires the appropriate activation and integration of three signals. The first signal is the antigen, which is presented in the context of the major histocompatibility complex, and its recognition by the T cell receptor (TCR). The first signal is not sufficient to activate T cells. Activation continues with a second signal that involves the participation of surface molecules expressed on dendritic cells that interact with their respective receptors on the T cell. The third signal involves the production of cytokines, which not only favor the activation state but also promote the polarization of T cells into their various helper/cytotoxic subpopulations[3,13] (Figure 1). In that dynamic microenvironment, the spatiotemporal expression of various co-stimulatory molecules on dendritic cells and T cells, as part of the second signal, is the key to regulating T cell activation, inhibition, survival, and polarization.

Co-stimulatory molecules are transmembrane glycoproteins that induce activation or inhibition cascades that enhance or diminish TCR signaling[14,15]. Stimulatory, or activating signals (co-stimulation by CD28 or CD40), lead to the production of growth factors, cell expansion, and survival. Inhibitory signals (co-inhibition by PD1 or CTL-4) attenuate TCR-induced signals, resulting in decreased cell activation, inhibition of growth factor production, inhibition of cell cycle progression, and in some cases, promotion of cell death[14].

Co-stimulatory molecules are divided into two main families by their molecular structure. The first (Table 1) is the immunoglobulin superfamily which includes CD226, the CD2/signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family, T cell immunoglobulin and mucin (TIM) family, butyrophilin (BTN) family, and leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor (LAIR) family. Because of its historical relevance, the most studied is the B7 family, which includes CD80, CD86, and its receptor CD28. The second (Table 2) is the tumor necrosis factor superfamily (TNFR SF), which includes three subfamilies, the divergent type (OX-40, CD27, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein), the S-type (CD267), and the conventional type [FAS, herpes virus entry mediator, receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (RANK), and CD40]. CD40 and its ligand CD40L are the most investigated co-stimulation molecules of the TNFR SF[3].

| IgSF co-stimulatory molecules | Function | Cells expressing the receptor | Ligand | Cells expressing the ligand |

| CD28 | Activation | Constitutive in T cells | CD80, CD86 | CD80: Inducible in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells. CD86: Constitutive in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells |

| ICOS (CD278) | Activation | Inducible in T, B, and NK cells | ICOSL | Constitutive in macrophages, dendritic cells, B and T cells |

| CTLA-4 (CD152) | Inhibition | Inducible in T cells | CD80, CD86 | CD80: Inducible in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells. CD86: Constitutive in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells |

| PD-1 (CD279) | Inhibition | Inducible in T, and B cells, macrophages | PD-L1, PD-L2 | PD-L1: Constitutive in dendritic cells, B and T cells. PD-L2: Inducible in dendritic cells and monocytes |

| PD-1H (VISTA) | Inhibition | Monocytes, neutrophils, T cells | Unknown | Unknown |

| BTLA (CD272) | Inhibition | B and T cells | HVEM, UL144 | Monocytes, B and T cells |

| B71 (CD80), B72 (CD86) | Activation/Inhibition | CD80: Inducible in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells. CD86: Constitutive in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells | CD28, CTLA-4 | CD28: Constitutive in T cells. CTLA-4: Inducible in T cells |

| B7H1 (CD274, PDL1) | Inhibition | Constitutive in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells | PD-1, B71 | PD-1: Inducible in macrophages, B and T cells. CD80: Inducible in dendritic cells, monocytes, B and T cells |

| TNFR SF co-stimulatory molecules | Function | Cells expressing the receptor | Ligand | Cells expressing the ligand |

| OX40 (CD134) | Activation | Activated and regulatory T cells | OX40L | T cells, macrophages, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, dendritic cells, tumor cells |

| CD27 (TNFR SF7) | Activation | T and B cells, NK cells | CD70 | NK, T and B cells |

| GITR (CD357) | Activation | T cells | GITRL | T cells |

| CD30 (TNFR SF8) | Activation | T and B cells | CD30L | T cells |

| HVEM (CD270) | Activation | Monocytes, T and B cells | LIGHT, BTLA, CD160, LTα3, HSV1gD | Monocytes and APCs |

| FAS (CD95) | Activation | NK and T cells | FASL | Dendritic cells, NK, T cells, neutrophils |

| CD40 (TNFR SF5) | Activation | All B-cell lineages except plasma cells, macrophages, activated monocytes, follicular dendritic cells, interdigitating dendritic cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts | CD40L | Activated CD4+ T cells, some CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, basophils, platelets monocytes and mast cells |

| RANK (CD265) | Activation | Osteoclast and dendritic cells | RANKL | Osteoblasts, T cells |

| TACI (CD267) | Inhibition | B and plasma cells | BAFF, APRIL | Stromal cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages |

The involvement of co-stimulatory molecules in clinical conditions has been explored. Mutations in ICOSL, CD40, or C267 have been associated with immunodeficiencies; increased expression of CD86, CD28, CD27, and CD70 has been reported in autoimmune diseases and allergies[16-23]. Some of the most interesting findings are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

| Molecule | Disease | Alteration | Ref. |

| CD86 | Rheumathoid arthritis | Increased expression in B cells | [16] |

| ICOSL | Combined immunodeficiency | Mutation | [17] |

| CTLA-4 | Mycosis fungoides | Increased expression in T cells | [18] |

| CD28 | Tuberculosis | Decreased expression in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells | [19] |

| CD28 | Graves’ disease | Increased expression in T cells | [20] |

| Molecule | Disease | Alteration | Ref. |

| CD27 | Lupus erythematosus | Increased expression in plasmablasts | [21] |

| CD70 | Lupus erythematosus | Increased expression in plasmablasts | [21] |

| CD40 | Hyper IgM Syndrome | Mutations | [22] |

| CD30 | Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis | Increased expression in T cells | [23] |

| CD267 | Common variable immunodeficiency | Mutations | [24] |

Numerous scientific studies have shown the involvement of co-stimulatory molecules in the regulation of the inflammatory process[3]. Subsequently, both experimental trials in various disease models and preclinical trials have demonstrated promising results achieved by the therapeutic manipulation of these molecules[24,25]. The preclinical results support their application at the clinical level either by inhibiting the function of activating co-stimulatory molecules to promote tolerogenic functions or by inhibiting inhibitory co-stimulatory molecules to promote pro-inflammatory functions.

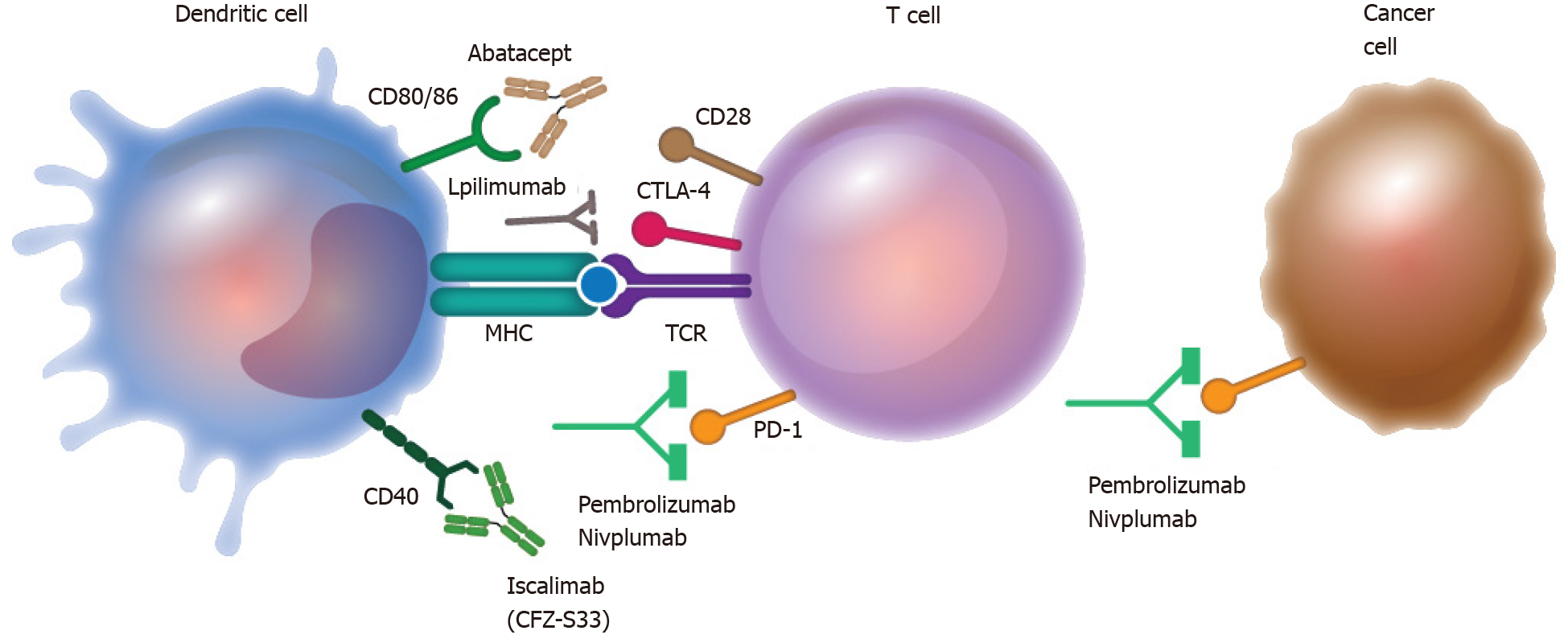

Blockade of the co-inhibitory molecules PD1 and CTLA-4 by the monoclonal antibodies pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, and nivolumab is a therapeutic indication in cancer treatment, particularly melanoma. On the other hand, therapeutic approaches for autoimmune diseases have exploited the blockade of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80/CD86 by abatacept or CD40 by iscalimab. In both cases, co-stimulatory molecule-targeted therapies have shown promising results[26-32] (Figure 2 and Table 5).

| Disease | Therapeutic target | Manipulation | Outcome | Ref. |

| Brain metastases melanoma | PD-1 and CTLA-4 | Blockade with mAbs (nivolumab + ipilimumab) | 55% of treated patients reduced tumor size. 21% showed full response | [27] |

| Melanoma | PD-1 | Blockade with mAbs (pembrolizumab or nivolumab) | 19% of treated patient reduced tumor size | [28] |

| Melanoma | PD-1 | Blockade with mAbs (pembrolizumab) | 33% of treated patient reduce size tumor | [29] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | CD80/CD86 | Blockade with soluble receptor (abatacept) | Reduction in the disease index | [30] |

| Psoriatic arthritis | CD80/CD86 | Blockade with soluble receptor (abatacept) | Musculoskeletal clinical improving | [31] |

| Sjögren syndrome | CD40 | Blockade with recombinant antibody (CFZ533 or iscalimab) | Reduction in the disease index | [32] |

| Kidney graft | CD40 | Blockade with recombinant antibody (CFZ533 or iscalimab) | Transplant success rate similar to tacrolimus treatment, but with a lower probability of adverse effects and infections | [33] |

Challenging limitations need to be overcome before these therapeutical tools are approved for clinical use[33]. Nevertheless, understanding the function and the possibility of therapeutic manipulation of co-stimulatory molecules represents a milestone for immunology and pharmacology. The knowledge gained from the study of co-stimulatory molecules has allowed a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of many diseases. The therapeutic use of these molecules has been well exploited in autoimmune diseases and oncology, where they serve as effective adjuvants to conventional therapy. However, we should not exclude the potential that these molecules have in many other contexts. They will undoubtedly continue to be an area of great interest for research and drug development.

| 1. | Weaver CT, Hawrylowicz CM, Unanue ER. T helper cell subsets require the expression of distinct costimulatory signals by antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8181-8185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2216] [Cited by in RCA: 2392] [Article Influence: 184.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kinnear G, Jones ND, Wood KJ. Costimulation blockade: current perspectives and implications for therapy. Transplantation. 2013;95:527-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bretscher P, Cohn M. A theory of self-nonself discrimination. Science. 1970;169:1042-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1250] [Cited by in RCA: 1184] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bretscher PA. The history of the two-signal model of lymphocyte activation: A personal perspective. Scand J Immunol. 2019;89:e12762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Roska AK, Lipsky PE. Dissection of the functions of antigen-presenting cells in the induction of T cell activation. J Immunol. 1985;135:2953-2961. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Jenkins MK, Pardoll DM, Mizuguchi J, Quill H, Schwartz RH. T-cell unresponsiveness in vivo and in vitro: fine specificity of induction and molecular characterization of the unresponsive state. Immunol Rev. 1987;95:113-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jenkins MK, Ashwell JD, Schwartz RH. Allogeneic non-T spleen cells restore the responsiveness of normal T cell clones stimulated with antigen and chemically modified antigen-presenting cells. J Immunol. 1988;140:3324-3330. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mueller DL, Jenkins MK, Schwartz RH. An accessory cell-derived costimulatory signal acts independently of protein kinase C activation to allow T cell proliferation and prevent the induction of unresponsiveness. J Immunol. 1989;142:2617-2628. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271:1734-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2582] [Cited by in RCA: 2910] [Article Influence: 97.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11:3887-3895. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ledford H, Else H, Warren M. Cancer immunologists scoop medicine Nobel prize. Nature. 2018;562:20-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:984-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1000] [Cited by in RCA: 1028] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu Z, Shen J, Wang MH, Yi T, Yu Y, Zhu Y, Chen B, Chen J, Li L, Li M, Zuo J, Jiang H, Zhou D, Luan J, Xiao Z. Comprehensive molecular profiling of the B7 family of immune-regulatory ligands in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1207841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Catalán D, Aravena O, Sabugo F, Wurmann P, Soto L, Kalergis AM, Cuchacovich M, Aguillón JC; Millenium Nucleus on Immunology and Immunotherapy P-07-088-F. B cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients show important alterations in the expression of CD86 and FcgammaRIIb, which are modulated by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Roussel L, Landekic M, Golizeh M, Gavino C, Zhong MC, Chen J, Faubert D, Blanchet-Cohen A, Dansereau L, Parent MA, Marin S, Luo J, Le C, Ford BR, Langelier M, King IL, Divangahi M, Foulkes WD, Veillette A, Vinh DC. Loss of human ICOSL results in combined immunodeficiency. J Exp Med. 2018;215:3151-3164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wong HK, Wilson AJ, Gibson HM, Hafner MS, Hedgcock CJ, Berger CL, Edelson RL, Lim HW. Increased expression of CTLA-4 in malignant T-cells from patients with mycosis fungoides -- cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:212-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Bernal-Fernandez G, Espinosa-Cueto P, Leyva-Meza R, Mancilla N, Mancilla R. Decreased expression of T-cell costimulatory molecule CD28 on CD4 and CD8 T cells of mexican patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberc Res Treat. 2010;2010:517547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bossowski A, Stasiak-Barmuta A, Urban M. Relationship between CTLA-4 and CD28 molecule expression on T lymphocytes and stimulating and blocking autoantibodies to the TSH-receptor in children with Graves' disease. Horm Res. 2005;64:189-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jacobi AM, Mei H, Hoyer BF, Mumtaz IM, Thiele K, Radbruch A, Burmester GR, Hiepe F, Dörner T. HLA-DRhigh/CD27high plasmablasts indicate active disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:305-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lanzi G, Ferrari S, Vihinen M, Caraffi S, Kutukculer N, Schiaffonati L, Plebani A, Notarangelo LD, Fra AM, Giliani S. Different molecular behavior of CD40 mutants causing hyper-IgM syndrome. Blood. 2010;116:5867-5874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Magaña D, Aguilar G, Linares M, Ayala-Balboa J, Santacruz C, Chávez R, Estrada-Parra S, Garfias Y, Lascurain R, Jiménez-Martínez MC. Intracellular IL-4, IL-5, and IFN-γ as the main characteristic of CD4+CD30+ T cells after allergen stimulation in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Mol Vis. 2015;21:443-450. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Romberg N, Chamberlain N, Saadoun D, Gentile M, Kinnunen T, Ng YS, Virdee M, Menard L, Cantaert T, Morbach H, Rachid R, Martinez-Pomar N, Matamoros N, Geha R, Grimbacher B, Cerutti A, Cunningham-Rundles C, Meffre E. CVID-associated TACI mutations affect autoreactive B cell selection and activation. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4283-4293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Esensten JH, Helou YA, Chopra G, Weiss A, Bluestone JA. CD28 Costimulation: From Mechanism to Therapy. Immunity. 2016;44:973-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 71.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ford ML, Larsen CP. Translating costimulation blockade to the clinic: lessons learned from three pathways. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:294-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, Hamid O, Hodi FS, Moschos SJ, Khushalani NI, Lewis K, Lao CD, Postow MA, Atkins MB, Ernstoff MS, Reardon DA, Puzanov I, Kudchadkar RR, Thomas RP, Tarhini A, Pavlick AC, Jiang J, Avila A, Demelo S, Margolin K. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Melanoma Metastatic to the Brain. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:722-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 960] [Cited by in RCA: 1030] [Article Influence: 128.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Beaver JA, Hazarika M, Mulkey F, Mushti S, Chen H, He K, Sridhara R, Goldberg KB, Chuk MK, Chi DC, Chang J, Barone A, Balasubramaniam S, Blumenthal GM, Keegan P, Pazdur R, Theoret MR. Patients with melanoma treated with an anti-PD-1 antibody beyond RECIST progression: a US Food and Drug Administration pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:229-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Kefford R, Joshua AM, Patnaik A, Hwu WJ, Weber JS, Gangadhar TC, Hersey P, Dronca R, Joseph RW, Zarour H, Chmielowski B, Lawrence DP, Algazi A, Rizvi NA, Hoffner B, Mateus C, Gergich K, Lindia JA, Giannotti M, Li XN, Ebbinghaus S, Kang SP, Robert C. Association of Pembrolizumab With Tumor Response and Survival Among Patients With Advanced Melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 857] [Article Influence: 85.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, Songcharoen S, Berman A, Nayiager S, Saldate C, Li T, Aranda R, Becker JC, Lin C, Cornet PL, Dougados M. Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1096-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mease PJ, Gottlieb AB, van der Heijde D, FitzGerald O, Johnsen A, Nys M, Banerjee S, Gladman DD. Efficacy and safety of abatacept, a T-cell modulator, in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1550-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fisher B, Zeher M, Ng WF, Bombardieri M, Posch M, Papas AS, Farag AM, Daikeler T, Bannert B, Kivitz AJ, Carsons SE, Isenberg DA, Barone F, Bowman S, Espie P, Wieczorek G, Moulin P, Floch D, Dupuy C, Ren X, Faerber P, Wright AM, Hockey HU, Rotte M, Rush JS, Gergely P. The Novel Anti-CD40 Monoclonal Antibody CFZ533 Shows Beneficial Effects in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Phase IIa Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trial Arthritis Rheumatol. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nashan B, Tedesco H, van den Hoogen MW. CD40 Inhibition with CFZ533 - A New, Fully Human, Non-Depleting, Fc Silent mAB - Improves Renal Allograft Function While Demonstrating Comparable Efficacy vs. Tacrolimus in De-Novo CNI-Free Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2018;102:S366. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chames P, Van Regenmortel M, Weiss E, Baty D. Therapeutic antibodies: successes, limitations and hopes for the future. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:220-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1021] [Cited by in RCA: 1250] [Article Influence: 73.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Immunology

Country/Territory of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gong N, Mankotia DS S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR