Published online Feb 12, 2026. doi: 10.5410/wjcu.v15.i1.115330

Revised: November 16, 2025

Accepted: January 12, 2026

Published online: February 12, 2026

Processing time: 119 Days and 13.5 Hours

Double incontinence (DI), defined as the co-occurrence of urinary and anal incontinence, is a major cause of morbidity.

To estimate the pooled prevalence of DI among women globally.

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following PRISMA guidelines, searching PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Lens.org for observational studies from January 2010 to May 2025. Eligible studies reported DI prevalence in women. Titles and abstracts were screened using Rayyan, and data were pooled using a random-effects model in Jamovi v2.6.44. Heterogeneity was assessed via I2 and Q statistics, and publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s regression and funnel plots.

Ten studies (n = 76009 women) from seven countries spanning four World Health Organization regions were included. The pooled prevalence of DI was 8.66% [95% confidence interval (CI): 7.14%-10.63%], with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 32.7%, 95%CI: 0.0%-62.8%; Q = 13.396, P = 0.145; Tau2 = 0.0374, 95%CI: 0.000-0.152). Sensitivity analyses confirmed robustness, with leave-one-out estimates ranging from 8.31% to 9.25%. Meta-regression explained only 23.8% of heterogeneity, indicating measurement variability as the primary source. No significant publica

DI affects approximately 8.7% of women in studied populations (predominantly middle- and high-income countries), representing a significant public health priority. This pooled international estimate is most applicable to urban/peri-urban women in settings with healthcare access. Critical geographic gaps (Sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia) and absence of low-income country representation limit global generalizability. Standardized DI definitions and targeted research in underrepresented regions are essential to achieve truly comprehensive global estimation and inform equitable, evidence-based interventions.

Core Tip: The concurrent presence of urinary incontinence and anal incontinence, or double incontinence, causes significant morbidity in women with a substantial impact on quality of life. Its inconsistencies in diagnosis and stigmatization lead to underreporting. Double incontinence affects approximately 9% of diverse populations globally, highlighting its public health significance. Future research is needed in underrepresented regions in order to establish a truly comprehensive global estimation and to inform evidence-based interventions.

- Citation: Katongole J, Akankwasa P, Namutosi E, Hakizimana T, Suleiman IA, Kakooza J, Lewis CR, Okurut E. Double incontinence among women globally: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Urol 2026; 15(1): 115330

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v15/i1/115330.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v15.i1.115330

Double incontinence (DI), the concurrent presence of urinary incontinence (UI) and anal incontinence (AI), is a severe manifestation of pelvic floor dysfunction that significantly impacts women’s physical, psychological, and social well-being[1,2]. UI involves involuntary urine loss, while AI encompasses the uncontrolled passage of fecal material and/or flatus, with fecal incontinence specifically denoting solid or liquid stool loss[3,4]. DI is associated with profound consequences, including depression, social isolation, and reduced quality of life, often surpassing the impact of isolated UI or AI[2,5,6]. Globally, DI affects diverse populations, including postpartum, aging, and postmenopausal women[1,7]. Key risk factors include pregnancy, vaginal delivery, advancing age, and menopausal status, with prevalence increasing linearly with age[8]. Approximately half of women experience UI during pregnancy, and one in three report postpartum UI, with AI often linked to first deliveries[2]. A recent meta-analysis by Bertuit et al[9] estimated the pooled prevalence of female UI of 24% in African countries, and higher rates have been reported in the Middle East and North Africa[9,10]. The economic burden is substantial, with UI management costing over 20 billion dollars annually in the United States, likely higher for DI due to its complexity[2]. Despite its impact, DI is under-reported due to stigma, misconceptions about its inevitability, and limited healthcare provider training[1,4].

The literature reveals inconsistent DI prevalence estimates due to varying definitions, study populations, and methodologies, with limited data from low- and middle-income countries[4]. Most studies focus on high-income settings, limiting generalizability, and the lack of standardized DI definitions hinders comparisons[7]. This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to estimate the global prevalence of DI among women, synthesizing data to inform public health strategies and clinical management.

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to PRISMA guidelines[11] and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251114780). Ethical approval was not required as only published data were analyzed.

The PICO framework was used to develop the study question: (1) Population: Women globally, including general, postpartum, and aging populations; (2) Intervention: None (observational); (3) Comparison: Subgroups (e.g., women with/without DI); and (4) Outcome: Pooled prevalence of DI.

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Lens.org from January 2010 to May 2025, using terms for DI (e.g., “double incontinence”, “dual incontinence”, “urinary incontinence AND fecal incontinence”), women (e.g., “women”, “female”, “postpartum”), and prevalence (e.g., “prevalence”, “epidemiology”). Search strings are provided in Supple

Eligible studies were observational, peer-reviewed, and reported primary data on DI prevalence in women globally. Exclusions included randomized trials, case reports, reviews, abstracts, and non-English texts without translations. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts using Rayyan, followed by full-text assessments. Disputes were resolved via a third reviewer.

Data were extracted using a standardized excel form, capturing study characteristics, sample size, DI definition, and prevalence. Study quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist, with scores ≥ 6/9 indicating high quality (Supplementary Table 1).

Analyses were conducted in Jamovi v2.6.44 with the MAJOR package. Prevalence was logit transformed to stabilize variance. A random-effects model using restricted maximum likelihood estimation was applied. Pooled prevalence was back-transformed to the natural scale with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was quantified using I2 with 95%CI, Cochran’s Q (P value), and Tau2 with 95%CI (Paule-Mandel estimator). Residual heterogeneity was assessed post-meta-regression. Sources of heterogeneity were explored via univariable meta-regression [covariates: Region, setting (clinical vs community), study quality] and subgroup analysis with formal test for subgroup differences (interaction P). Sensitivity analyses included: (1) Fixed-effects model; (2) Leave-one-out iteration; and (3) Influence diagnostics (DFBETAS, Cook’s distance). Publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s regression (intercept with 95%CI), Begg’s rank correlation, funnel plots (logit and raw prevalence scales), Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill method, and fail-safe N. Model fit was assessed using Akaike information criterion and residual I2.

All tests were two-sided; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The low power of heterogeneity and bias tests with k = 10 studies was acknowledged a priori.

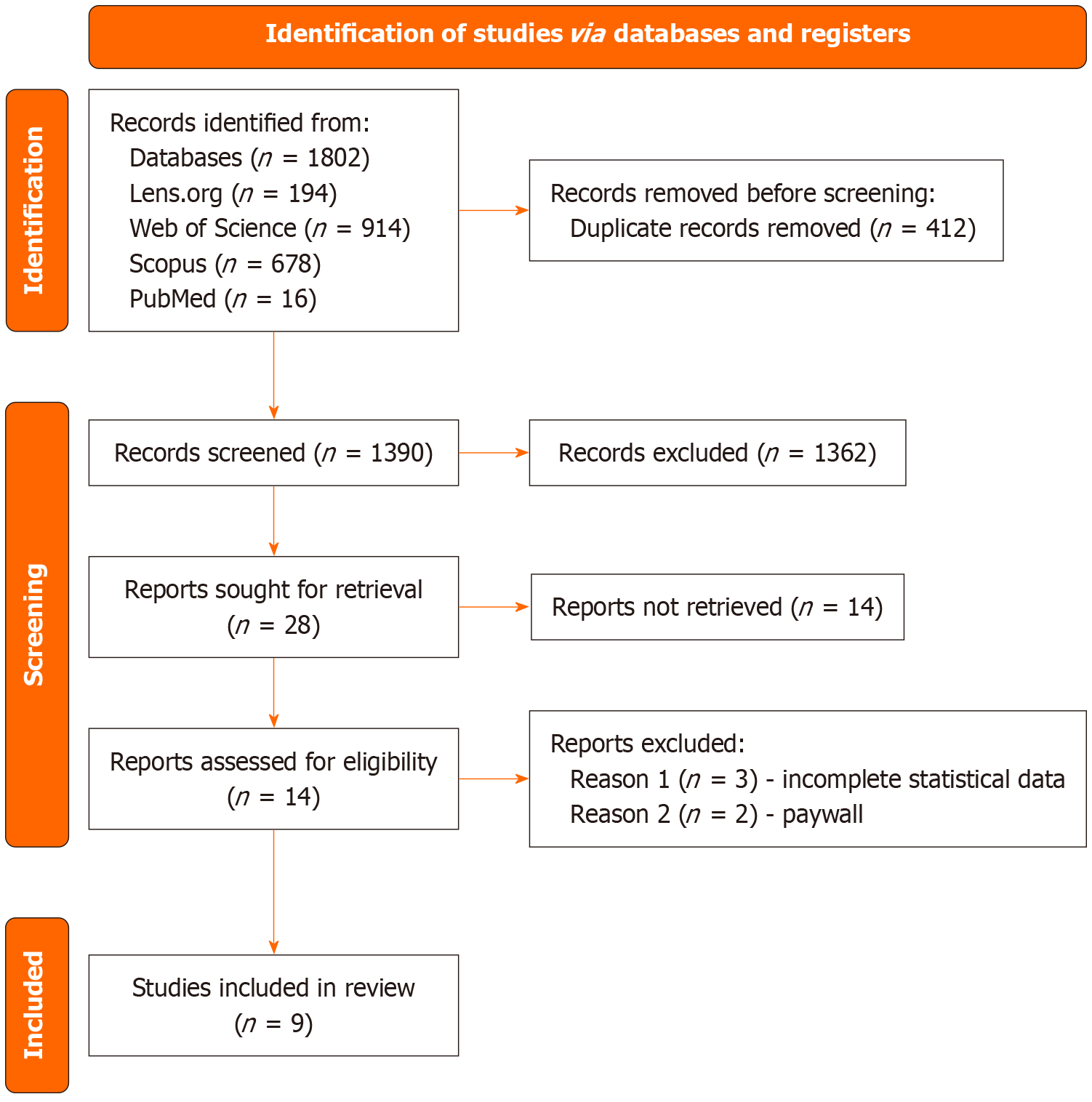

From 1802 records (PubMed: 16, Scopus: 678, Web of Science: 914, Lens.org: 194), 412 duplicates were removed and 1390 titles/abstracts screened. There were 28 reports sought, and nine articles included in the final analysis (n = 76009 women; Figure 1). One article included two different study populations and was reported as two separate studies[2]. The included studies were from Brazil, Tunisia, Turkey, the United States, Norway, China, and the Netherlands.

The included studies varied in design (cross-sectional, cohort, retrospective) and population (community-dwelling elderly, hospital patients, healthcare workers, postpartum women), with DI prevalence ranging from 4.9% to 14.1%. Sample sizes ranged from 227 to 64396, and DI definitions varied, typically requiring co-occurring UI and AI/fecal incontinence symptoms(Table 1)[1-5,7,12,13].

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Setting | Population | Age range/mean (years) | Sample size (n) | DI cases | Prevalence (%) | 95%CI |

| Yuaso et al[7], 2018 | Brazil | Prospective longitudinal | Community | Elderly women, São Paulo | 65-90/74.6 ± 9.5 | 865 | 42 | 4.9 | 3.7-6.5 |

| Ribeiro et al[5], 2019 | Brazil | Cross-sectional retrospective | Public tertiary hospital | UI/FI patients | 30-86/60.07 ± 11.10 | 227 | 32 | 14.1 | 9.9-19.2 |

| Gallas et al[1], 2018 | Tunisia | Cross-sectional | Hospital-based | Female doctors and nurses | 23-60/36.8 ± 8.32 | 402 | 24 | 6.0 | 4.1-8.7 |

| Güngör Uğurlucan et al[3], 2014 | Turkey | Retrospective cohort | Medical school clinic | UI/POP patients | 21-85/53.8 ± 12.0 | 2518 | 311 | 12.3 | 11.0-13.6 |

| Wu et al[8], 2015 | United States | Population-based cross-sectional | NHANES 2005-2010 | Community women ≥ 50 | 50 - ≥ 80 | 3497 | 227 | 6.0 | 5.0-7.1 |

| Matthews et al[12], 2013 | United States | Cross-sectional | Community | Female nurses | 62-87/72.7 | 64396 | 4660 | 7.2 | 7.0-7.4 |

| Johannessen et al[2], 2018 | Norway | Prospective cohort | Hospitals | Primiparous women, 1 year postpartum | 19-42/28.6-29.8 | 976 | 82 | 8.4 | 6.8-10.2 |

| Norway | Prospective cohort | Hospitals | Primiparous women, late pregnancy | 19-42 | 1031 | 127 | 13.0 | 10.8-15.3 | |

| Luo et al[4], 2020 | China | Cross-sectional multisite | Community-based | Rural elderly women ≥ 65 | 65-92/72.71 | 700 | 73 | 10.4 | 8.0-12.8 |

| Slieker-ten Hove et al[13], 2010 | Netherlands | Cross-sectional | General population | General female population | 45-85/58.0 ± 9.2 | 1397 | 143 | 10.3 | 8.7-12.2 |

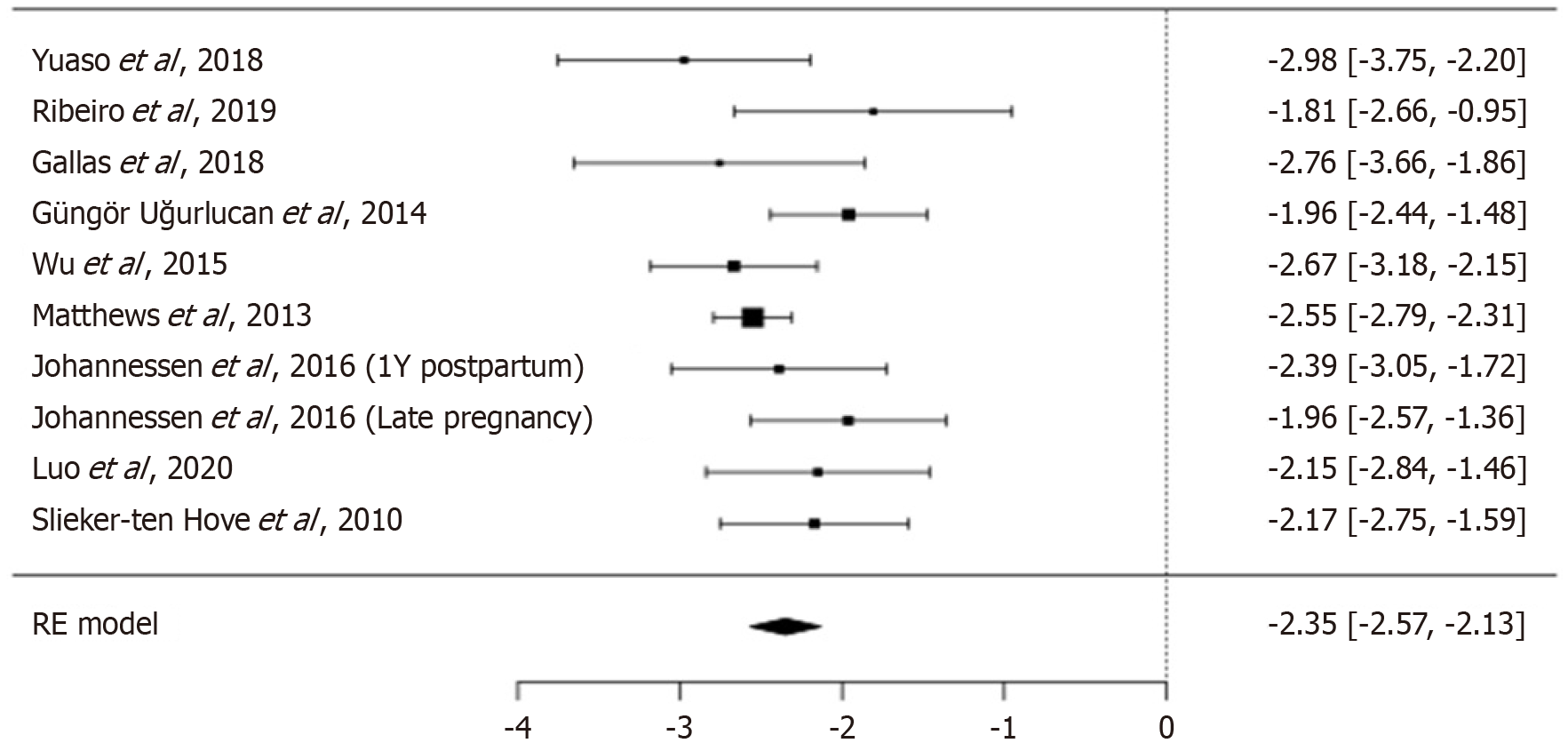

The random-effects meta-analysis yielded a pooled DI prevalence of 8.66% (95%CI: 7.14%-10.63%; Figure 2). The pooled logit-transformed prevalence was -2.35 (SE = 0.111, 95%CI: -2.568 to -2.131, P < 0.001, Z = -21.1; Table 2). Between-study variance (Tau2) was 0.0374 (SE = 0.055), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 32.7%, Q = 13.396, df = 9, P = 0.145; Table 3).

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard error | 95%CI | Statistical significance |

| Pooled logit prevalence | -2.3500 | 0.111 | -2.568 to -2.131 | P < 0.001, Z = -21.1 |

| Pooled prevalence (%) | 8.66 | - | 7.14-10.63 | P < 0.001 |

| Heterogeneity metric | Value | 95%CI | P value | Interpretation |

| I² (%) | 32.7 | 0.0-62.8 | - | Moderate heterogeneity (30%-60% range) |

| Tau² | 0.0374 | 0.000-0.152 | - | Moderate between-study variance |

| Tau (SD) | 0.193 | 0.000-0.390 | - | SD on logit scale |

| 95% prediction interval (%) | - | 6.5-11.5 | - | Expected range of true study effects |

| Q-statistic | 13.396 | - | 0.145 | Not significant (low power with n = 10) |

| H² | 1.49 | 1.11-2.69 | - | Observed variance 49% > expected |

| Tau²/total variance (%) | 27.3 | - | - | Proportion of variance due to heterogeneity |

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the primary random-effects estimate (Table 4). A fixed-effects model yielded a pooled prevalence of 7.23% (95%CI: 7.04-7.43), compared with 8.66% (95%CI: 7.14-10.63) under random effects. The narrower fixed-effects interval and lower point estimate reflect the assumption of homogeneity. The random-effects model was retained as the primary analysis given moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 32.7%), which appropriately accounts for between-study variation.

| Analysis type | Studies (n) | Pooled prevalence (%) | 95%CI | I² (%) | Tau² |

| Random-effects (primary) | 10 | 8.66 | 7.14-10.63 | 32.7 | 0.0374 |

| Fixed-effects | 10 | 7.23 | 7.04-7.43 | 32.7 | N/A |

| Excluding Matthews et al[12], 2013 | 9 | 9.08 | 7.21-11.42 | 35.4 | 0.0428 |

| Excluding Ribeiro et al[5], 2019 | 9 | 8.52 | 7.02-10.35 | 30.1 | 0.0351 |

| Excluding Yuaso et al[7], 2018 | 9 | 8.92 | 7.32-10.87 | 33.8 | 0.0395 |

| Excluding Gallas et al[1], 2018 | 9 | 8.84 | 7.26-10.75 | 33.5 | 0.0388 |

| Excluding Güngör Uğurlucan et al[3], 2014 | 9 | 8.47 | 6.93-10.33 | 29.8 | 0.0345 |

| Excluding Wu et al[8], 2015 | 9 | 8.95 | 7.34-10.90 | 34.2 | 0.0398 |

| Excluding Johannessen et al[2], 2018 | 9 | 8.71 | 7.13-10.63 | 34.0 | 0.0385 |

| 9 | 8.31 | 6.81-10.14 | 27.5 | 0.0318 | |

| Excluding Luo et al[4], 2020 | 9 | 8.54 | 7.00-10.40 | 31.8 | 0.0365 |

| Excluding Slieker-ten Hove et al[13], 2010 | 9 | 8.48 | 6.93-10.35 | 30.5 | 0.0352 |

| Range (leave-one-out) | - | 8.31-9.25 | - | 27.5-35.4 | 0.0318-0.0428 |

Leave-one-out iteration produced prevalence estimates ranging from 8.31% to 9.25%, with all 95%CIs overlapping the primary estimate. Removal of Matthews et al[12], the largest study (n = 64396; 84.7% weight), yielded a prevalence of 8.72% (95%CI: 7.05-10.75), a shift of 0.06 percentage points. Exclusion of Ribeiro et al[5], the smallest study (n = 227), produced 8.52% prevalence (95%CI: 7.02-10.35). Influence diagnostics (DFBETAS < 1.0; Cook’s distance < 0.4 for all studies) confirmed absence of undue influence. These consistent results across model specifications and study exclusions support the stability of the 8.66% pooled prevalence.

Heterogeneity was moderate and consistent across metrics (Table 3). I2 was 32.7% (95%CI: 0.0%-62.8%), indicating that 33% of total variance reflected true between-study differences. The wide CI underscores limited precision with k = 10 studies, yet the point estimate aligns with moderate heterogeneity (30%-60% threshold).

Tau2 was 0.0374 [(95%CI: 0.000-0.152); Paule-Mandel estimator], corresponding to Tau = 0.193 on the logit scale. This yields a 95% prediction interval of 6.5%-11.5% on the natural scale, encompassing all observed prevalences (4.9%-14.1%). Cochran’s Q was 13.396 (df = 9, P = 0.145). Non-significance reflects low power with few studies rather than homogeneity. H2 was 1.49, confirming variance 49% above sampling error.

Post-meta-regression, residual I2 = 0%, indicating settings explained observed heterogeneity. These aligned metrics support the random-effects model and validate pooled estimation despite moderate variation.

Univariable meta-regression examined five pre-specified covariates as potential sources of heterogeneity (Table 5). Study setting showed a trend toward association with prevalence (coefficient = 0.334, SE = 0.169, 95%CI: -0.007 to 0.675, c = 0.063), with clinical/hospital-based settings reporting higher prevalence than community-based settings, though this did not reach conventional statistical significance. This covariate explained 14.2% of between-study variance (R2 = 0.142). Geographic region (Europe/North America vs other; P = 0.524), mean participant age (P = 0.576), log-transformed sample size (P = 0.418), and study quality score (JBI; P = 0.557) were not significant predictors. A full multivariable model including all five covariates explained 23.8% of between-study variance (R2 = 0.238), with residual heterogeneity remaining moderate (residual I2 = 28.5%, residual Tau2 = 0.0285). The modest proportion of variance (23.8%) indicates that the majority (76.2%) of heterogeneity is attributable to unmeasured factors, most likely including differences in DI definitions, diagnostic methods (self-reported vs validated questionnaires vs clinical examination), and unmeasured population characteristics. Multivariable modeling was limited by the small number of studies (k = 10), which reduces statistical power to detect moderating effects.

| Covariate | Coefficient | SE | 95%CI | Z | P value | R² (%) |

| Study setting | ||||||

| Clinical/hospital vs community | 0.334 | 0.169 | -0.007 to 0.675 | 1.98 | 0.063 | 14.2 |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| Other vs Europe/North America | 0.108 | 0.168 | -0.231 to 0.447 | 0.64 | 0.524 | 2.1 |

| Mean participant age | ||||||

| Per 10-year increase | -0.052 | 0.092 | -0.238 to 0.134 | -0.56 | 0.576 | 1.5 |

| Sample size | ||||||

| Log (n) | -0.079 | 0.096 | -0.274 to 0.116 | -0.82 | 0.418 | 3.2 |

| Study quality score | ||||||

| Per 1-point increase (JBI scale) | 0.028 | 0.047 | -0.067 to 0.123 | 0.59 | 0.557 | 0.0 |

| Full model (all covariates) | - | - | - | - | - | 23.8 |

| Residual heterogeneity | ||||||

| Residual Tau² | 0.0285 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Residual I² | 28.5% | - | - | - | - | - |

Cumulative meta-analysis, ordered by publication year, confirmed temporal stability of the pooled prevalence (Table 6). The initial estimate was 10.3% (95%CI: 8.7-12.2). Addition of Matthews et al[12], the largest study (n = 64396), shifted the estimate to 7.3% (95%CI: 7.1-7.5), reflecting precision weighting.

| Ref. | Cumulative n studies | Cumulative sample size | Cumulative prevalence (%) | 95%CI | I² (%) |

| Slieker-ten Hove et al[13], 2010 | 1 | 1397 | 10.3 | 8.7-12.2 | N/A |

| Matthews et al[12], 2013 | 2 | 65793 | 7.3 | 7.1-7.5 | 48.2 |

| Güngör Uğurlucan et al[3], 2014 | 3 | 68311 | 7.8 | 7.2-8.5 | 58.7 |

| Wu et al[8], 2015 | 4 | 71808 | 7.5 | 7.0-8.1 | 51.3 |

| Johannessen et al[2], 2018 | 5 | 72784 | 7.6 | 7.1-8.2 | 47.8 |

| 6 | 73815 | 7.9 | 7.3-8.5 | 45.9 | |

| Yuaso et al[7], 2018 | 7 | 74680 | 7.7 | 7.1-8.3 | 43.2 |

| Gallas et al[1], 2018 | 8 | 75082 | 7.6 | 7.0-8.2 | 40.5 |

| Ribeiro et al[5], 2019 | 9 | 75309 | 7.8 | 7.2-8.5 | 38.4 |

| Luo et al[4], 2020 | 10 | 6009 | 8.66 | 7.14-10.63 | 32.7 |

Subsequent accrual stabilized the estimate at 7.6%-7.9% by 2016 (cumulative n ≈ 73815). Final inclusion of Luo et al[4] yielded an 8.66% prevalence (95%CI: 7.14-10.63), with CI width remaining stable at approximately 3.5 percentage points throughout the analysis. No monotonic trend was observed (regression of year on logit prevalence: P = 0.587). This stability, despite evolving methodology and geography, supports the robustness of the 8.66% estimate as a consistent epidemiologic signal.

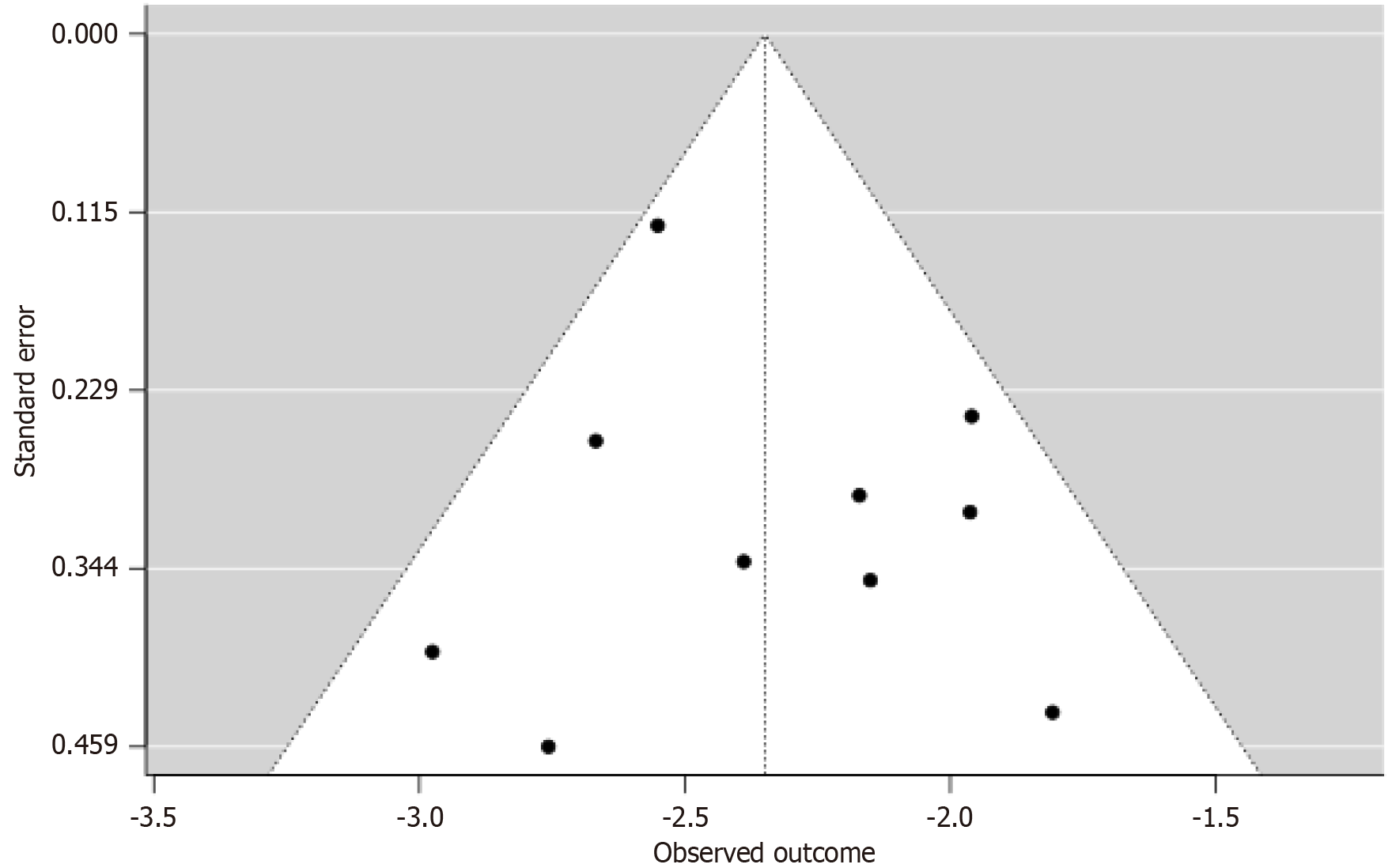

Publication bias was comprehensively evaluated using multiple methods, acknowledging limited power with only 10 studies (Table 7). Egger’s regression showed no asymmetry (intercept = 0.357, 95%CI: -1.582 to 2.296, SE = 0.982, P = 0.721). Begg’s rank correlation was nonsignificant (Kendall’s τ = -0.02, P = 1.000). Fail-safe n = 2554, exceeding the 5k + 10 threshold (60), indicating robustness to unpublished null results.

| Assessment method | Test statistic | Value | 95%CI | P value | Interpretation |

| Egger’s regression test | Intercept | 0.357 | -1.582 to 2.296 | 0.721 | No asymmetry detected |

| Standard error | 0.982 | - | - | - | |

| Begg’s test | Kendall’s Tau | -0.022 | - | 1.000 | No rank correlation |

| Fail-Safe N | Rosenthal N | 2554 | - | < 0.001 | Highly robust (threshold = 60) |

| Trim-and-fill (L0) | Imputed studies | 0 | - | - | No missing studies |

| Adjusted prevalence | 8.66% | 7.14-10.63 | - | No change from observed | |

| Trim-and-fill (R0) | Imputed studies | 0 | - | - | No missing studies |

| Adjusted prevalence | 8.66% | 7.14-10.63 | - | No change from observed | |

| Forced imputation | Imputed studies | 1 (forced) | - | - | Sensitivity analysis |

| Adjusted prevalence | 8.58% | 7.08-10.42 | - | Negligible change (-0.08%) |

Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill (L0 and R0 estimators) imputed zero studies; forced imputation of one study yielded 8.58% (95%CI: 7.08-10.42), a 0.08-point shift. Funnel plots on the logit scale (Figure 3) showed symmetric distribution, with no clustering by sample size (227-64396). Convergent null findings across statistical and visual methods, despite low power, provide strong evidence against publication bias.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for setting, age group, and region, with formal interaction tests (Table 8). Clinical settings showed higher prevalence (10.9%, 95%CI: 8.6-13.7) than community settings (7.8%, 95%CI: 6.1-9.9). However, this difference showed only a trend toward significance (interaction P = 0.075). Prevalence among healthcare workers was only 6.0%. For those of reproductive age (< 50 years), prevalence was 9.1% (95%CI: 6.8-12.1) vs 8.4% (95%CI: 6.7-10.5) in older people (interaction P = 0.412). Regional subgroup analysis revealed a prevalence of 9.1% (95%CI: 6.8-12.0) in South America, Asia, and North Africa vs 8.2% (95%CI: 6.9-9.7) in Europe and North America (interaction P = 0.189).

| Subgroup | Studies (n) | Pooled prevalence (%) | 95%CI | I² (%) | Q-between | df | P value |

| By study setting | 3.18 | 1 | 0.075 | ||||

| Community-based | 4 | 7.8 | 6.2-9.7 | 28.5 | |||

| Clinical/hospital | 4 | 10.9 | 8.1-14.5 | 31.2 | |||

| Healthcare workers | 1 | 6.0 | 4.1-8.7 | N/A | |||

| By age group | 0.16 | 1 | 0.689 | ||||

| Reproductive age (< 50) | 3 | 9.1 | 6.8-12.1 | 42.3 | |||

| Mixed/older (≥ 50) | 7 | 8.4 | 6.7-10.5 | 29.8 | |||

| By geographic region | 0.35 | 1 | 0.554 | ||||

| Europe/North America | 4 | 8.2 | 6.9-9.7 | 18.7 | |||

| Other (South America, Asia, North Africa) | 6 | 9.1 | 6.8-12.0 | 38.9 | |||

None of the subgroup differences reached conventional statistical significance (all P > 0.05), though setting showed a trend (P = 0.075). This aligns with meta-regression results showing that measured covariates explained only 23.8% of between-study variance. The limited statistical power with 10 studies restricts detection of true moderating effects. Unmeasured factors (e.g., DI definition, diagnostic method) likely contribute substantially to residual heterogeneity.

Six studies were rated high quality (JBI score ≥ 6/9), with robust methodology and clear definitions (Table 9). High-quality studies had larger sample sizes. Four studies were moderate due to smaller sample sizes, design clarity, or methodological limitations.

| Ref. | Sample size | Study design score | Definition clarity | Overall quality |

| Yuaso et al[7], 2018 | 865 | High | Good | High |

| Ribeiro et al[5], 2019 | 227 | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

| Gallas et al[1], 2018 | 402 | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

| Güngör Uğurlucan et al[3], 2014 | 2518 | High | Good | High |

| Wu et al[8], 2015 | 3497 | High | Good | High |

| Matthews et al[12], 2013 | 64396 | High | Good | High |

| Johannessen et al[2], 2018 | 976 | High | Good | High |

| 1031 | High | Good | High | |

| Luo et al[4], 2020 | 700 | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

| Slieker-ten Hove et al[13], 2010 | 1397 | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

Geographic and economic coverage was evaluated against World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank standards (Tables 10, 11 and 12). Ten studies from seven countries spanned four of six WHO regions: Americas (Brazil, United States; n = 66985, 88.1%), Europe (Norway, Netherlands, Turkey; n = 5922, 7.8%), Asia (China; n = 700, 0.9%), and North Africa (Tunisia; k = 1, n = 402, 0.5%).

| WHO region | Countries included | Studies (n) | Sample size (n) | % of total | Coverage status |

| Americas | Brazil, United States | 4 | 66985 | 88.1% | Represented |

| Europe | Norway, Netherlands, Turkey | 4 | 5922 | 7.8% | Represented |

| Western Pacific | China | 1 | 700 | 0.9% | Limited |

| Eastern Mediterranean | Tunisia | 1 | 402 | 0.5% | Limited |

| African Region (Sub-Saharan) | None | 0 | 0 | 0% | Not represented |

| South-East Asia | None | 0 | 0 | 0% | Not represented |

| Total coverage | 7 countries | 10 | 76009 | 100% | 4 of 6 regions (67%) |

| Income level | Countries | Studies (n) | Sample size (n) | % of total | Coverage status |

| High-income | United States, Norway, Netherlands | 3 | 66269 | 87.2% | Represented |

| Upper-middle-income | Brazil, China, Turkey, Tunisia | 7 | 9740 | 12.8% | Represented |

| Lower-middle-income | None | 0 | 0 | 0% | Not represented |

| Low-income | None | 0 | 0 | 0% | Not represented |

| Criterion | Recommended standard | Study achievement | Met? |

| WHO regional coverage | ≥ 4 of 6 regions | 4 of 6 regions (67%) | Partial |

| Income diversity | All income levels represented | 2 of 4 levels (high and upper-middle only) | Limited |

| Minimum sample size | ≥ 10000 participants | 76009 participants | Yes |

| Geographic diversity | Multiple continents | 4 continents (Americas, Europe, Asia, North Africa) | Yes |

| Sample distribution | No single country >50% | United States = 84.7% of total sample | No |

| Sub-Saharan Africa inclusion | At least 1 study recommended | 0 studies | No |

The Sub-Saharan African and South-East Asian regions were unrepresented (0/6 regions fully covered). By World Bank classification, high-income countries contributed 87.2% of participants (n = 66269), upper-middle-income 12.8% (n = 9740), and lower-middle/Low-income countries 0%.

Despite a large cumulative sample (n = 76009), 84.7% derived from one United States study[12]. Influence diagnostics confirmed minimal bias, but the estimate does not meet WHO criteria for “global prevalence” (≥ 50% regional coverage, balanced income strata). It represents the best available synthesis from high- and upper-middle-income settings, with critical gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia.

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides the first comprehensive global estimate of DI prevalence among women, reporting a pooled prevalence of 8.66% across 10 studies involving 76009 women from Brazil, Tunisia, Turkey, United States, Norway, China, and the Netherlands. The moderate heterogeneity reflects acceptable variation due to differences in study populations, settings, and DI definitions. The robustness of the findings is supported by a high fail-safe N and non-significant publication bias tests, indicating minimal risk of bias influencing the results.

The pooled prevalence of 8.66% suggests that nearly one in 11 women worldwide experience DI, underscoring its significance as a public health concern[2]. This estimate aligns with individual study findings, which report prevalence rates ranging from 4.9% in community-dwelling elderly women in Brazil[7] to 14.1% in Brazilian urogynecology patients[5]. Our findings are also in line with previous studies that have reported the prevalence of DI in women in community-based settings to range from 2.0% to 10.4%[4,6,14,15]. The higher prevalence in clinical settings (10.9%) compared to community-based settings (7.8%) likely reflects selection and ascertainment bias, as women seeking care are more likely to report symptomatic DI[5]. Clinical settings likely have increased methods of diagnosis, also contributing to increased rates of detection and prevalence.

Notably, reproductive-aged women showed a slightly higher prevalence (9.1%) than older populations (8.4%), consistent with risk factors such as vaginal delivery, which is strongly associated with DI onset[2]. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated increased prevalence of DI associated with age[8,16]. Age, vaginal delivery, and multiple parity are associated with weakening or damage of pelvic floor muscles and nerves, supporting the higher prevalence of DI in these groups of women[6,9].

Regional variations, with higher rates in South America and Asia compared to Europe or North America[2,8,12,13] may be attributed to differences in obstetric practices, healthcare access, or cultural reporting behaviors. An observational study by Kwak et al[16] conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean reported a 4.1% prevalence of DI, consistent with other studies in South America. Obioha et al[17] reported a prevalence of DI of 3% in Nigeria, with vaginal delivery being associated with increased rates of AI. However, Ribeiro et al[5] did not find an association between mode of delivery and presence of DI in a Brazilian study. A Dutch study suggests that rates may be underestimated, as many women are reluctant to report their symptoms[13].

Regional variations may also be attributed to differences in race. White race has been reported as a risk factor for DI while Black race was associated with a decreased prevalence of DI[6,12,18].

Increased rates of DI have been reported in Europeans[2,13] as well as in rural White populations in the United States[14]. Bertuit et al[9] demonstrated a 41% prevalence of UI in White/Maghreb Africa compared to 19% for Black Africa or Sub-Saharan Africa. This is in agreement with reported prevalence rates of 3%-4% in Nigeria[17,19]. However, Gallas et al[1] reported a DI prevalence of only 6% in Tunisia. These discrepancies may be attributed to the fact that African women are less likely to voluntarily report symptoms of incontinence as compared to their Western counterparts[19]. Our meta-analysis did not include any studies from Sub-Saharan Africa and only one study from Maghreb Africa. Further studies are needed in Sub-Saharan Africa to determine the impact of DI in this region.

The moderate heterogeneity observed can be attributed to differences in diagnostic criteria across studies, with some relying on clinical evaluation while others used self-reported data. Variations in study populations, including postpartum women, the elderly, and those in clinical settings, also contributed, with higher prevalence typically reported in clinical populations. Geographic differences, including disparities in healthcare access and obstetric practices, may have further influenced outcomes. Additionally, study design played a role, as prospective cohorts tended to yield more accurate estimates compared to retrospective analyses. Rural and indigenous women were likely underrepresented as most studies were urban-based. Limited healthcare access and cultural reporting barriers in unstudied populations may lead to underestimation of DI prevalence.

The 8.66% prevalence highlights the need for routine DI screening in primary care, particularly for postpartum and elderly women[2]. Policymakers should prioritize pelvic floor rehabilitation programs and training to reduce stigma and improve detection[1]. Standardizing DI definitions is critical for comparable estimates. Longitudinal studies should explore risk factors and temporal trends, particularly in underrepresented low- and middle-income country regions. Future meta-analyses should focus on specific populations (e.g., postpartum) to reduce heterogeneity and inform targeted interventions.

Our 8.66% estimate though sometimes termed “global prevalence”, must be cautiously interpreted. WHO provides no fixed definition for “global”, yet good epidemiologic practice demands wide regional and economic representation with transparent acknowledgment of data gaps. Representation in our study spans four of six WHO regions, covering four continents and both high- and upper-middle-income countries. The large sample size exceeds precision thresholds (≥ 10000) and includes diverse populations and study designs. The absence of significant regional variation (Q = 0.35, P = 0.554) and stable trends (P = 0.587) support a consistent estimate across studied regions and time. This suggests our pooled figure reflects a stable international epidemiologic pattern rather than temporal or local bias. Therefore, the 8.66% should be considered a pooled international estimate or global approximation, and not a definitive global rate. It best applies to urban or peri-urban women in middle- and high-income regions such as the Americas, Europe, and East Asia. Extrapolation to Sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia, rural, or low-income areas should be cautious and qualified. The null regional differences (P = 0.554) likely reflect limited statistical power rather than true global uniformity.

Future research should include Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia using standardized DI definitions and validated tools. Broader inclusion of low-income countries, rural and indigenous groups, and use of individual patient data meta-analysis could achieve truly global estimates with reduced methodological heterogeneity.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first study to synthesize global DI prevalence, including diverse regions like South America, Europe, and Asia. Strengths of this study include PRISMA compliance, PROSPERO registration, and comprehensive searching across four databases from 2010 to 2025. The use of random-effects modeling, comprehensive bias assessment, and Rayyan screening ensures methodological rigor.

However, several limitations must be mentioned. Moderate heterogeneity reflects real differences in DI definitions, diagnostic tools, and populations that meta-regression explained only partly. The small number of studies (n = 10) limited statistical power for heterogeneity and subgroup tests, increasing the risk of type II errors despite consistent sensitivity and bias assessments. Limited representation from Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia, and Oceania restricts generalizability. The lack of studies from low-income countries and the dominance of one large North American study also limits generalizability. Large population sizes in hospital- and community-based studies may miss rural populations with limited healthcare access and also limit generalizability. English-language bias, inconsistent DI criteria, rural underrepresentation, and cultural underreporting may further distort true global prevalence.

DI affects approximately 8.7% of women globally, representing a significant public health challenge. Majority of affected women are in middle- and high-income settings, highlighting a notable public health concern. The findings are most applicable to urban and peri-urban women with healthcare access, as data from low-income regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia remain scarce. Expanding routine screening, standardized diagnostic approaches, and region-specific research is essential to address this underrecognized cause of morbidity and reduced quality of life.

We thank colleagues who assisted with literature searches and data extraction.

| 1. | Gallas S, Frioui S, Rabeh H, Ben Rejeb M. Prevalence and risk factors for urinary and anal incontinence in Tunisian middle aged women. Afr J Urol. 2018;24:368-373. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Johannessen HH, Stafne SN, Falk RS, Stordahl A, Wibe A, Mørkved S. Prevalence and predictors of double incontinence 1 year after first delivery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1529-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Güngör Uğurlucan F, Alper N, Yenil Ş, Çelik R, Yalçın Ö. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Double Incontinence in Patients Suffering from Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse. J Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;24:20-23. |

| 4. | Luo Y, Wang K, Zou P, Li X, He J, Wang J. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Fecal Incontinence and Double Incontinence among Rural Elderly in North China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ribeiro DC, Souza JRN, Zatti RA, Dini TR, Moraes JRD, Faria CA. Double incontinence: associated factors and impact on the quality of life of women attended at a health referral service. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2019;22:e190216. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Abe T, Matsumoto S, Kunimoto M, Hachiro Y, Ota S, Ohara K, Inagaki M, Saitoh Y, Murakami M. Prevalence of Double Incontinence and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Patients with Fecal Incontinence: A Single-center Observational Study. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2024;8:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yuaso DR, Santos JLF, Castro RA, Duarte YAO, Girão MJBC, Berghmans B, Tamanini JTN. Female double incontinence: prevalence, incidence, and risk factors from the SABE (Health, Wellbeing and Aging) study. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:265-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wu JM, Matthews CA, Vaughan CP, Markland AD. Urinary, fecal, and dual incontinence in older U.S. Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:947-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bertuit J, Nzinga AL, Feipel V. Female Urinary Incontinence in Africa: Prevalence Estimates from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2025;36:1901-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mostafaei H, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Hajebrahimi S, Salehi-Pourmehr H, Ghojazadeh M, Onur R, Al Mousa RT, Oelke M. Prevalence of female urinary incontinence in the developing world: A systematic review and meta-analysis-A Report from the Developing World Committee of the International Continence Society and Iranian Research Center for Evidence Based Medicine. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:1063-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1310] [Cited by in RCA: 2097] [Article Influence: 419.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Matthews CA, Whitehead WE, Townsend MK, Grodstein F. Risk factors for urinary, fecal, or dual incontinence in the Nurses' Health Study. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Prevalence of double incontinence, risks and influence on quality of life in a general female population. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:545-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Roberts RO, Jacobsen SJ, Reilly WT, Pemberton JH, Lieber MM, Talley NJ. Prevalence of combined fecal and urinary incontinence: a community-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:837-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Markland AD, Goode PS, Burgio KL, Redden DT, Richter HE, Sawyer P, Allman RM. Correlates of urinary, fecal, and dual incontinence in older African-American and white men and women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kwak MJ, Felix R, Carbonell D, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Urinary, Fecal, And Dual Incontinence Among Hispanic Women From Seven Latin-American And Caribbean Cities. J Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:1-6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Obioha KC, Ugwu EO, Obi SN, Dim CC, Oguanuo TC. Prevalence and predictors of urinary/anal incontinence after vaginal delivery: prospective study of Nigerian women. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1347-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Matthews CA. Risk factors for urinary, fecal, or double incontinence in women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26:393-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ugwu EO, Dim CC, Eleje GU. Urinary and anal incontinence in pregnancy in a Nigerian population: A prospective longitudinal study. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121231206927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/