Published online Feb 12, 2026. doi: 10.5410/wjcu.v15.i1.114046

Revised: October 2, 2025

Accepted: January 12, 2026

Published online: February 12, 2026

Processing time: 148 Days and 8.2 Hours

Bladder diverticulum refers to an outpouching of the bladder wall. This condition can involve only the bladder mucosa or extend to include the entire lining of the bladder wall, including the muscles. Bladder diverticula can be congenital or ac

Core Tip: A bladder diverticulum is the outpouching of the bladder wall, which can be congenital or acquired, affecting individuals of all ages. Congenital cases are more common in the young, while acquired ones typically occur in adults. Although rare, it can cause significant distress due to recurrent infections or urinary symptoms. Diagnosis relies on clinical evaluation and imaging. Management has evolved from non-surgical to various surgical approaches, including laparoscopic and robotic-assisted techniques. It emphasizes a management strategy predicated on first identifying and treating the underlying cause of outlet obstruction, which may obviate the need for complex diverticulectomy in selected cases. This review presents a practical approach supported by imaging and operative techniques for easier understanding.

- Citation: Khalid A, Obadele OG, Alabi TO, Nedjim SA, Abdulwahab-Ahmed A, Mungadi IA. Practical approach to the review of bladder diverticulum and its management. World J Clin Urol 2026; 15(1): 114046

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v15/i1/114046.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v15.i1.114046

Bladder diverticulum refers to the outpouching of bladder mucosa between the fibers of the detrusor muscle, resulting in a thin-walled structure that connects to the bladder lumen through an opening known as an ostium or neck. The size of the muscular defect can influence whether the diverticulum has a narrow or wide neck. The wall of the diverticulum consists of urothelium, lamina propria, scattered thin muscle fibers, and an adventitial layer, but it lacks a functional muscularis propria[1]. The muscle fibers are densely packed around the neck of the diverticulum, gradually decreasing in density in the side walls, and are sparse at the dome[2]. Bladder diverticula are uncommon but not rare, and they can affect individuals of any sex or age group. In the pediatric population, the incidence is about 1.7%, but it is more pre

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation and imaging studies. Radiographic examination often confirms the diagnosis while investigating vague symptoms such as hematuria, dysuria, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). The condition can cause significant distress due to pain from recurrent infections or discomfort stemming from lower urinary tract symptoms. Management of bladder diverticula may include non-surgical treatments, open surgery, laparoscopic or robotic-assisted surgical excision, and endoscopic procedures. Asymptomatic cases or those without aggravating conditions may be monitored and surveilled. In long-standing cases or with large diverticula, an open surgical approach may be beneficial, and addressing any underlying causes is crucial to prevent recurrence. This paper aims to review the literature on bladder diverticulum and its management, accompanied by investigative and operative images which are included to enhance clarity and comprehension.

Congenital or primary bladder diverticula, also known simply as primary diverticula, are more frequently observed in the pediatric population, particularly in boys under the age of 10[3]. These diverticula are most often solitary and large, typically found in a bladder with a smooth wall, and are rarely associated with malignancy. They are primarily located superolateral to the ureteric orifice and may either engulf, impinge upon, or remain separate from the vesicoureteric junction, with or without associated vesicoureteric reflux (VUR)[6,7]. Additionally, they have been noted in association with various congenital syndromes, including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Williams syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, and Menkes syndrome[8-10].

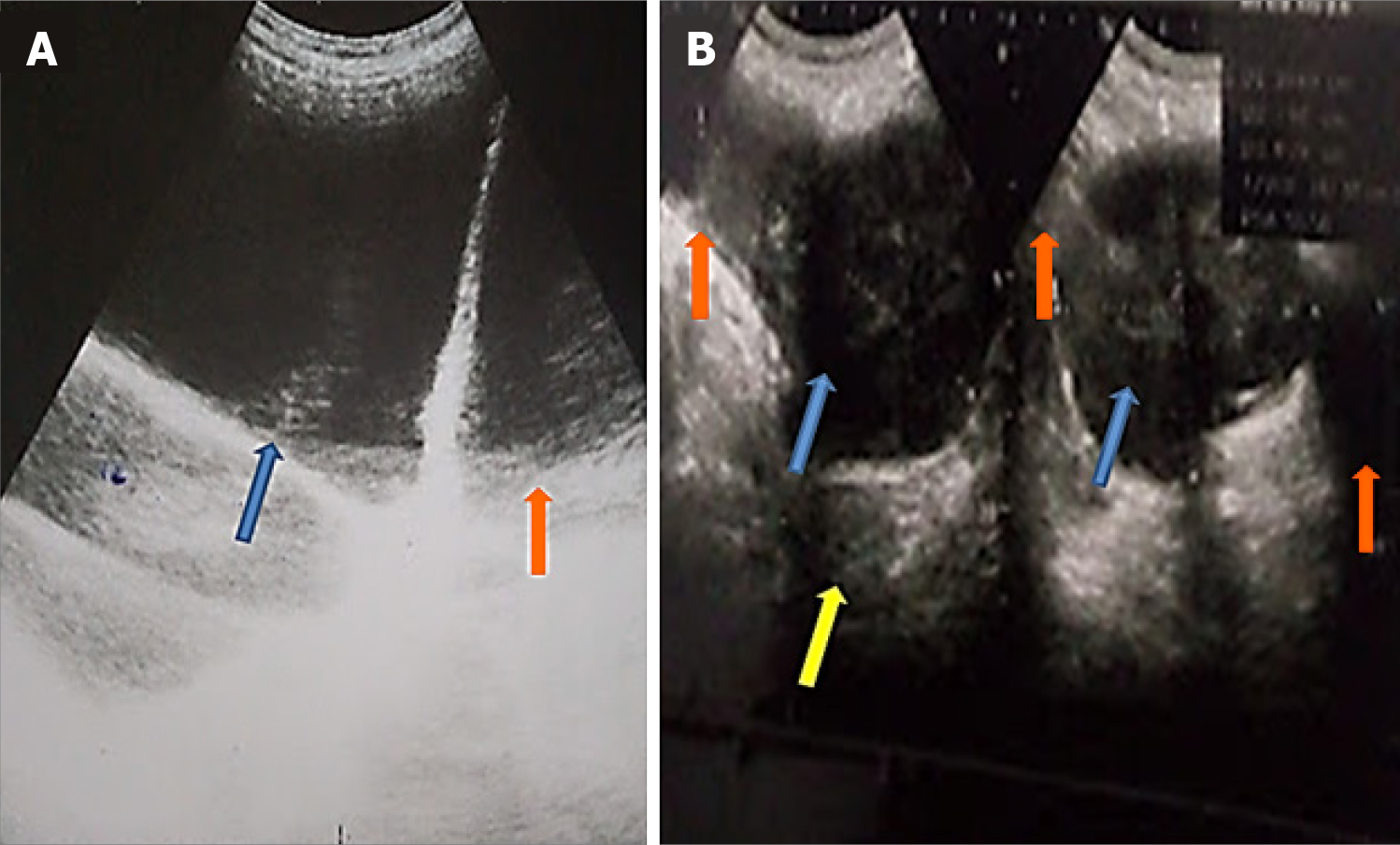

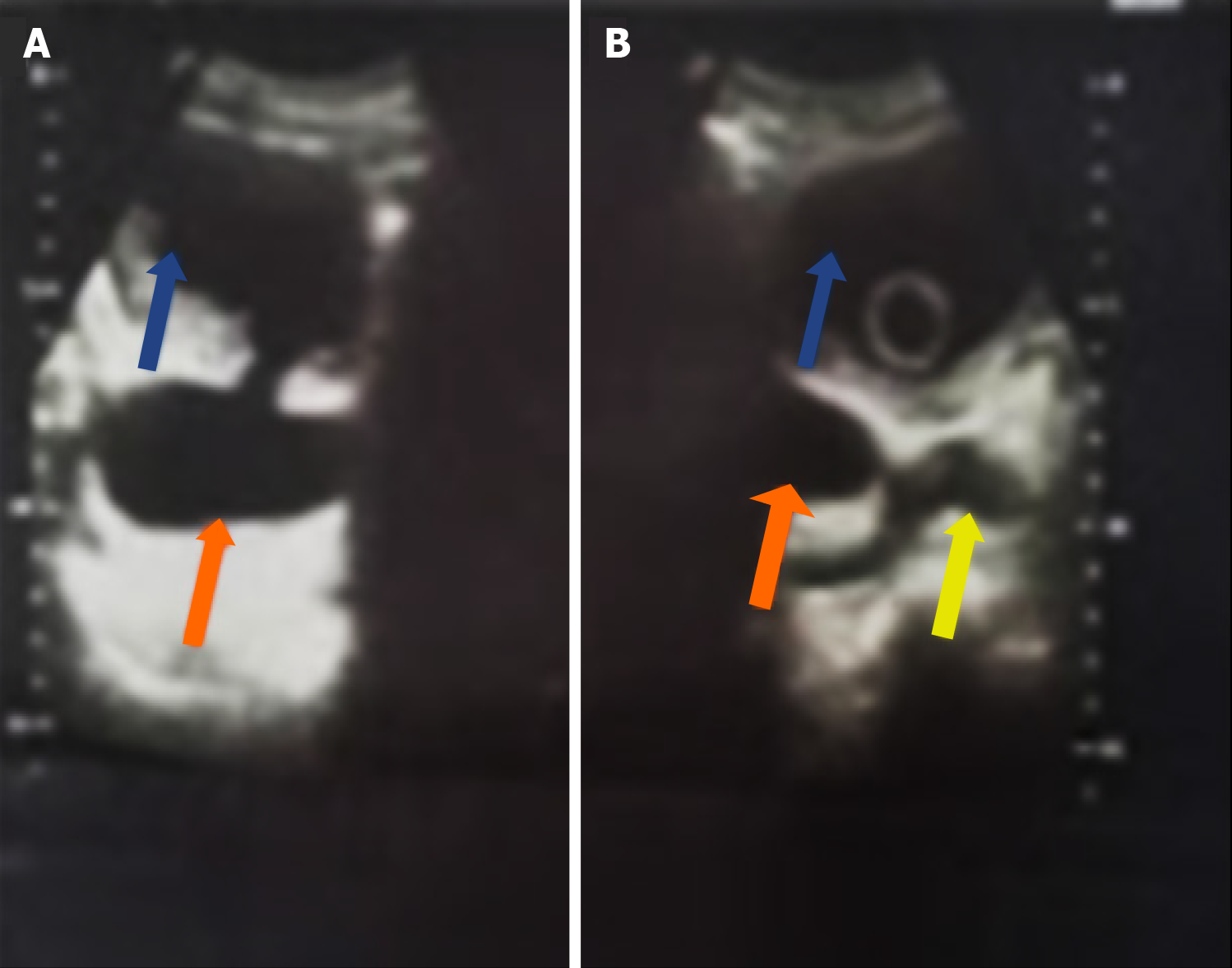

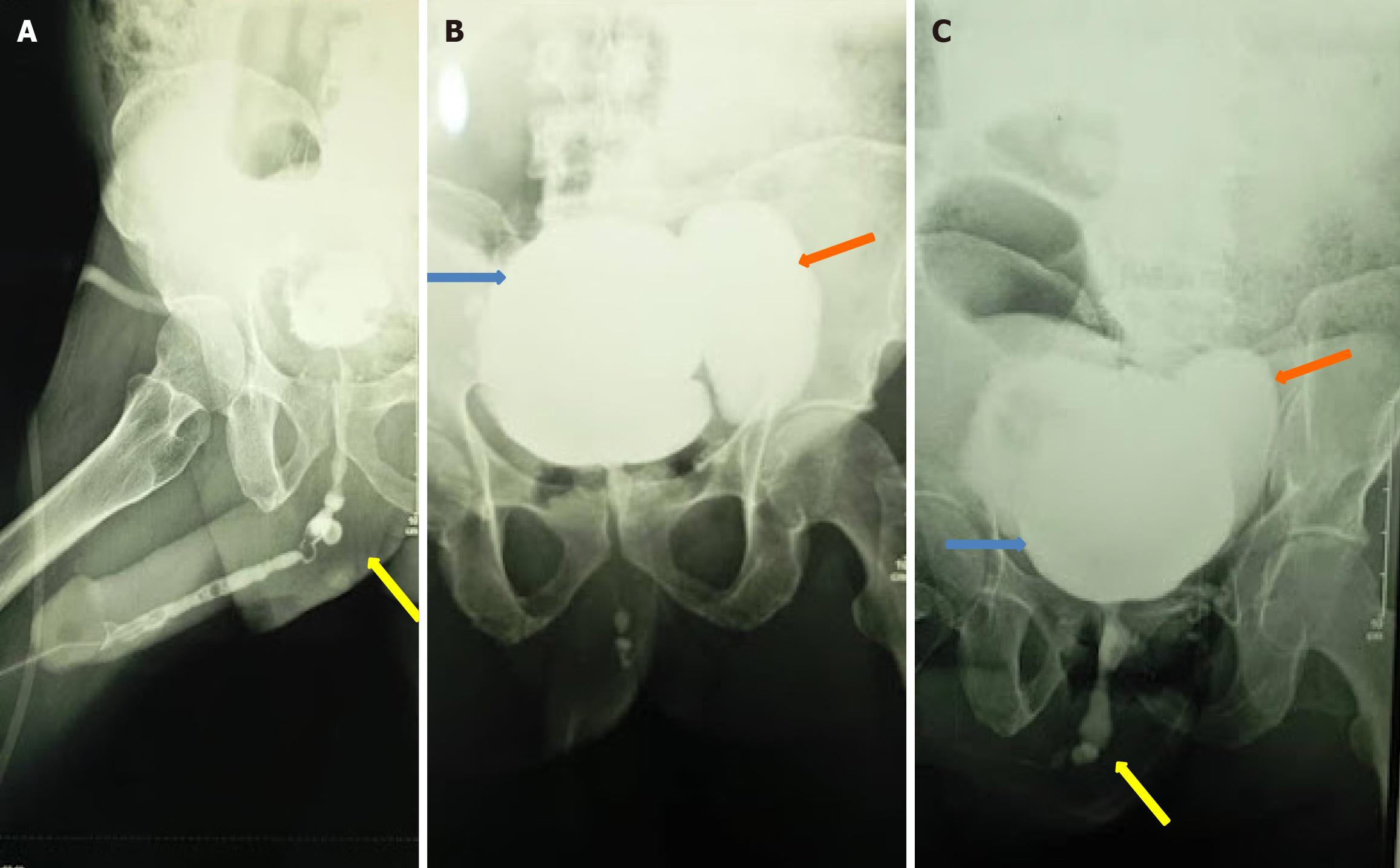

Acquired or secondary diverticula, by contrast, are commonly found in adults over the age of 60, with a male-to-female ratio of 9:1[1,4]. These diverticula are usually multiple and are located in trabeculated, thick-walled bladders. They may be associated with primary malignancies in 0.8% to 13% of cases[11]. Acquired diverticula can occur anywhere in the bladder but are more frequently found at weak points, such as the ureterovesical junction and the bladder dome. The development of acquired diverticula is often the result of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO), which can be caused by conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (Figures 1, 2, and 3), urethral stricture disease (Figure 4), repeated infections, or iatrogenic factors. In children, secondary diverticula can arise from various obstructions. For example, in boys with posterior urethral valves, these diverticula can serve as a pressure relief mechanism to protect the kidneys from damage and maintain bladder function[2]. When a diverticulum includes the ureteral orifice in the context of a neurogenic bladder along with VUR, it is referred to as a “Hutch” diverticulum[12].

Congenital bladder diverticula are a developmental failure of the detrusor musculature, typically resulting from its hypoplasia, predominantly involving the Waldeyer fascial sheath[6]. Acquired diverticula, on the other hand, are the result of BOO, repeated infection or iatrogenic causes. Obstruction at the bladder neck or along the urethra raises bladder voiding pressures. It pushes the bladder mucosa through the gap in the detrusor musculature of the bladder wall to form a sac[13]. Some of the causes of BOO include prostate enlargement, urethral stricture, neurogenic bladder, posterior urethral valves, anterior urethral diverticulum, and detrusor external sphincter dyssynergia. These diverticula frequently resolve after treatment of the outlet obstruction, especially when small. Severe and recurrent UTI have also been implicated in the pathophysiology of secondary diverticula[2]. It is thought that inflammation weakens the bladder muscle and leads to diverticula formation in the absence of outlet obstruction. Bladder diverticula may also be iatrogenic. It is usually the result of mucosa protrusion through a weak point in the suture line after an inadequate reapproximation of the muscular layers of the bladder wall during cystotomy repair or antireflux surgery[1,14,15].

Bladder diverticula may increase in size to the extent that they compress the bladder neck or proximal urethra, resulting in a vicious cycle. The increased outlet resistance stimulates additional filling of the diverticulum during micturition, with a resultant cumulative enlargement of the diverticulum and worsening of obstruction[2]. A giant bladder diverticulum refers to one with a size greater than 10 cm × 8 cm or over 150 mL in volume[16]. A huge bladder diverticulum may herniate through the femoral or inguinal canal, forming a part of the hernia sac, an entity known as a sliding hernia[17,18]. Also, a diverticulum may incorporate the ureteral orifice, resulting in VUR, although it remains unclear whether the paraureteral diverticulum causes reflux or is merely associated with it. Spontaneous perforation of a congenital bladder diverticulum is a rare occurrence but has been reported, and can result in morbid outcomes if detected late[19,20]. Malignancy, which could be urothelial, sarcomatous or mixed in origin, can occur within a bladder diverticulum. Intradiverticular tumours occur almost exclusively in adults, and the transitional cell carcinoma has the highest incidence of 70%-80%. They tend to be more aggressive than their bladder counterparts, due to the lack of a defined detrusor musculature with a potential for early extravesical disease extension[21].

Bladder diverticula can sometimes have no impact on a person's health, but in other cases, they can cause vague and nonspecific symptoms. Often, bladder diverticula are discovered accidentally during imaging studies or endoscopic procedures performed for unrelated issues, such as UTI, haematuria, or lower urinary tract symptoms[1].

When bladder diverticula are large, the symptoms are typically linked to urinary stasis, which occurs when the bladder fails to empty completely during urination. This can lead to a feeling of fullness in the lower abdomen. Patients may report discomfort from inadequate bladder emptying and the need to void multiple times.

The most common issue arising from primary bladder diverticula is acute UTI due to stasis, which may present symptoms such as fever, painful urination, and lower abdominal or loin pain[22]. In some cases, large bladder diverticula may cause nonspecific abdominal symptoms, including gastrointestinal obstruction, dyspepsia, epigastric pain, and a palpable abdominal mass. In rare situations, they may lead to an acute abdomen due to spontaneous rupture[19,23,24]. There have also been cases of inguinal hernias containing bladder diverticula.

Other less common manifestations include acute urinary retention, enuresis, bladder stones, hematuria, and the potential development of malignancy due to chronic irritation from prolonged contact of the diverticular mucosa with carcinogenic substances[25-27].

The initial evaluation of a bladder diverticulum involves gathering a comprehensive medical history and conducting a thorough physical examination, which includes a digital rectal examination. However, the diagnosis of bladder diverticula primarily depends on radiographic and endoscopic findings.

Abdominal ultrasonography is an economical and readily available option with no risk of radiation exposure; however, it has low sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing bladder diverticula. On ultrasound, a diverticulum appears as an anechoic cavity that communicates with the urinary bladder (Figures 1 and 2). Additionally, significant post-void residual urine may also be detected through ultrasonography.

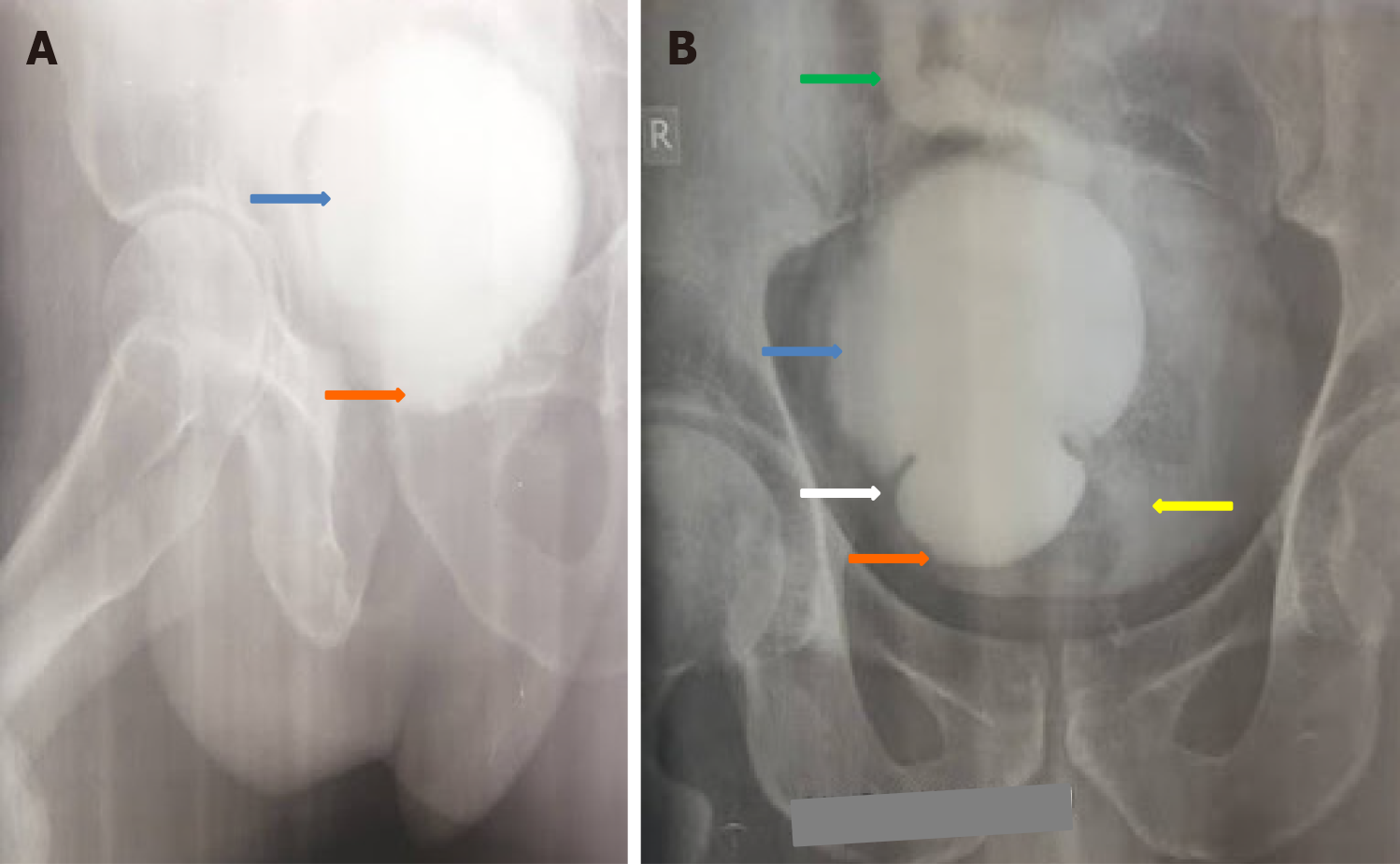

Contrast imaging studies are vital in identifying the underlying etiology of BOO and confirming the presence of bladder diverticula. The retrograde urethrogram is used to diagnose urethral strictures (Figure 4). The voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), including anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views, confirms bladder diverticula (Figures 3, 4, and 5). Furthermore, the VCUG provides information regarding the location, number, size, anatomy, any associated VUR, and importantly, post-void residual volume[1]. Bladder diverticula are part of a radiological continuum that includes cellules and saccules[1]. A fluoroscopically monitored VCUG is an excellent study for detecting bladder diverticula, as an anomalous voiding into the diverticulum with its paradoxical enlargement may be observed. This occurs due to contrast outflow from the relatively high-pressure bladder into the low-pressure diverticulum during detrusor contraction.

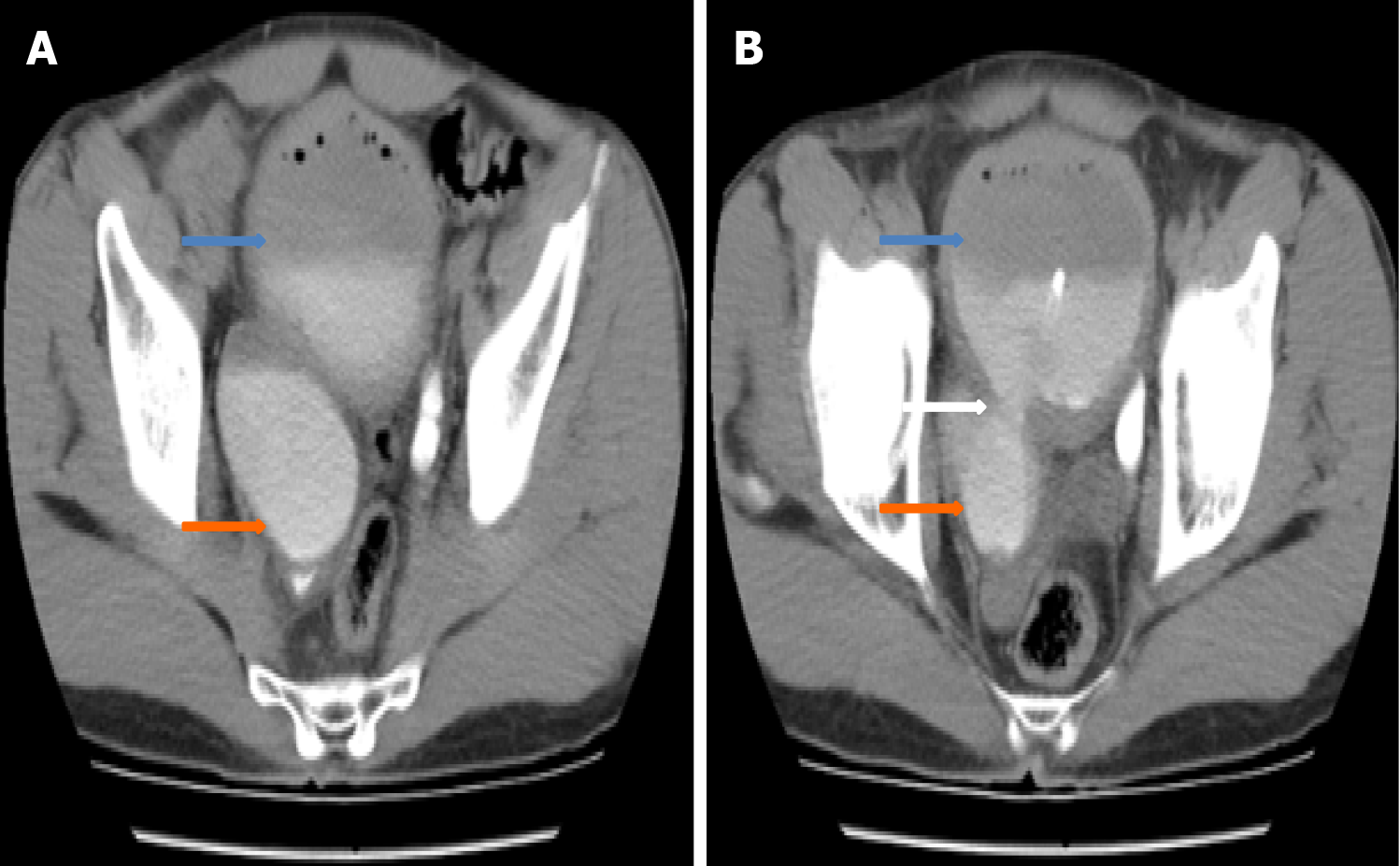

A contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) scan (Figure 6) provides cross-sectional images of the lower urinary system and offers additional information, such as thickened bladder wall, medial or lateral deviation of the ipsilateral ureter, intradiverticular tumors and their loco-regional spread, and stones within the diverticulum[28,29]. Magnetic resonance imaging may complement the findings of previous investigations or be utilized in cases where a diagnostic dilemma remains unresolved after other imaging studies, particularly in complicated bladder diverticula cases.

Preoperative urodynamic studies are very useful in identifying underlying abnormalities such as BOO, impaired compliance, and/or neurogenic voiding dysfunction. Addressing these issues may potentially resolve the patient’s symptoms[1].

Endoscopic examination of the interior of diverticula is best performed via flexible cystoscopy. Identifying the size and location of the diverticula relative to the ureters and bladder outlet is crucial for proper surgical planning[1]. This is particularly important in laparoscopic bladder diverticulectomy, where the endoscopic light guides the initial dissection. Ideally, urine for cytology should be obtained from the diverticulum, and biopsies of any abnormal epithelium or lesions within the diverticulum should be taken cautiously to avoid perforation during the endoscopy.

The bladder diverticular wall is composed of several layers, including urothelium, lamina propria (or subepithelial connective tissue), scattered thin muscle fibers, and adventitia[1,27]. Congenital diverticula typically include all layers of the bladder wall, while acquired diverticula lack the muscularis propria. Often, there is an outer shell made of a fibrous capsule or pseudocapsule, which can create a suitable surgical plane for excision. While some muscle fibers can be observed around the neck of the diverticulum, they progressively decrease in number along the side walls and are least present at the dome[2]. Other common findings may include inflammation, erosion, and granulation tissue formation. Large bladder diverticula may empty poorly during micturition due to a hypoplastic or absent muscularis propria layer.

Bladder diverticula are often discovered accidentally during radiological examinations, appearing as fluid-filled cavities near the bladder. They can be misdiagnosed as similar conditions, including bladder ears, hourglass bladder, vesical hernias, ectopic ureters, ureteroceles, and postoperative lymphoceles[28]. Other potential differential diagnoses include urachal cysts, prostatic utricle cysts, Müllerian duct cysts, and blind-ending bifid ureters. Additionally, less common congenital conditions to consider are vesicourethral diverticulum, incomplete bladder duplication, and bladder septation[29].

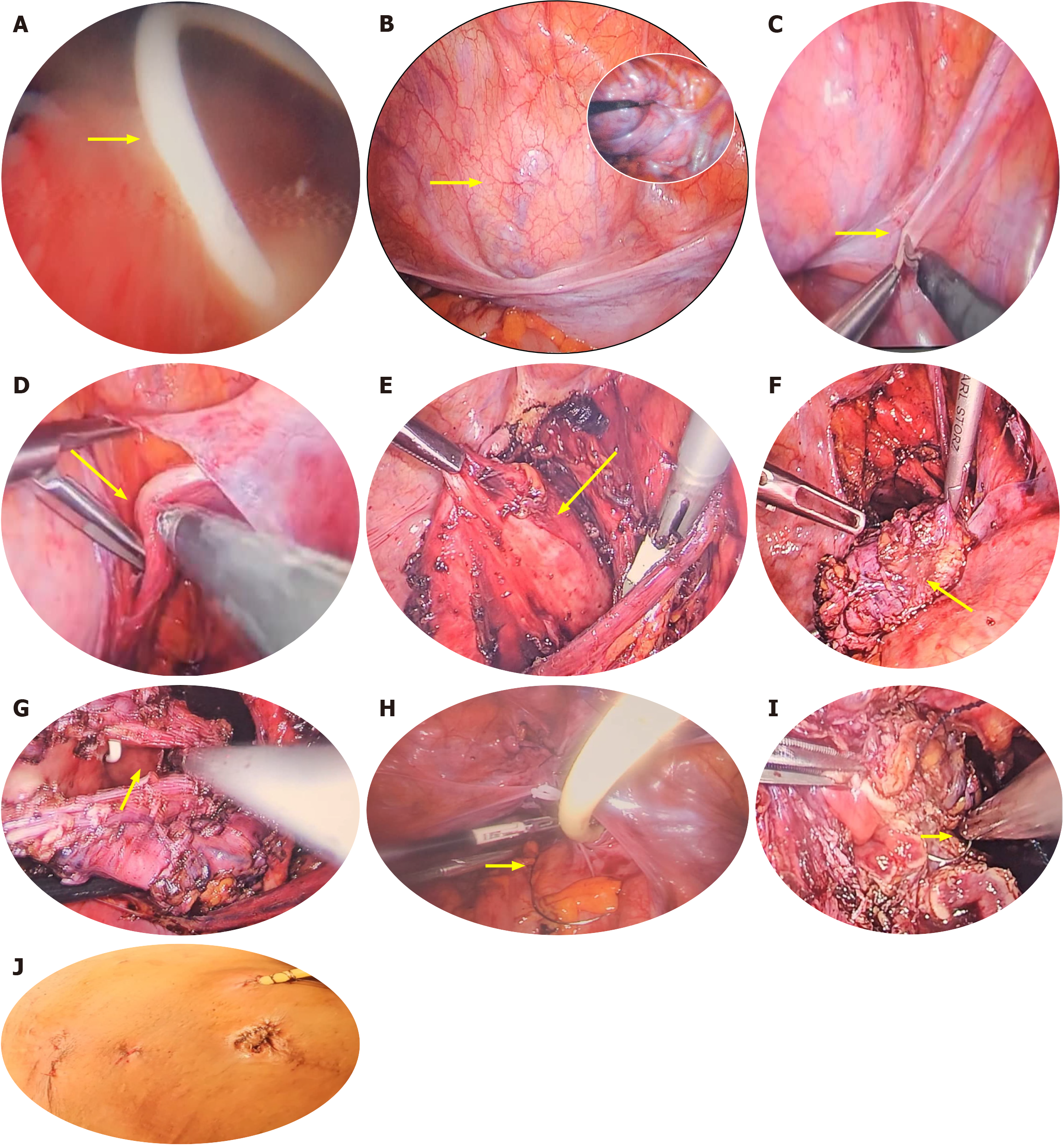

Management options for treating bladder diverticula include expectant management, open surgical excision, laparoscopic or robotic surgical excision, and endoscopic care. Many factors must be considered when deciding on the appropriate therapy. If BOO is determined to be the cause of a secondary diverticulum, it should be treated definitively before or concurrently with a formal diverticulectomy (Figures 7 and 8). Also, it must be stated that treating the BOO alone can often lead to resolution or significant improvement of secondary diverticula, making formal excision unnecessary in many cases (Figure 7). In cases of primary bladder diverticulum, particularly with paraureteral diverticula, a successful paraureteral diverticulectomy typically suffices. This is because the lower urinary tract symptoms or BOO in these cases usually result from the compression of the bladder neck by the paraureteral diverticulum during voiding (Figures 5, 6, and 9).

Non-surgical therapy using an indwelling catheter or clean intermittent catheterization is intended for patients with inadequate bladder emptying after addressing BOO, or for those who are either unwilling or unable to undergo surgical excision. If treating the underlying BOO leads to satisfactory emptying of the diverticulum, surgery may not be necessary, and only monitoring should be initiated. Diverticular surveillance includes urine microscopy and culture, urine cytology, and periodic cystoscopy. Additionally, upper tract monitoring through ultrasonography and renal function assessment is recommended.

Surgical intervention becomes necessary if the diverticulum is symptomatic or if complications arise, such as diverticular stones, chronic relapsing UTIs, carcinoma, or deteriorating urinary tract conditions due to VUR or obstruction.

Endoscopic management involves transurethral resection (TUR) of the diverticular neck, which may be combined with fulguration of the entire urothelium of the diverticulum[27]. This approach is beneficial for patients who are older, unfit for laparoscopic surgery, or those requiring TUR of the prostate alongside a poorly draining diverticulum. The procedure includes making multiple incisions at the diverticular ostium and deepening them to the muscular fibers of the bladder wall, using either an infraumbilical knife or a resectoscope loop[1]. Although this technique widens the neck of the diverticulum, facilitating improved drainage during voiding, it does carry a risk of urinary retention due to reversed flow into the low-pressure diverticulum. Combining this method with fulguration of the lining of the diverticulum can significantly reduce its size or lead to obliteration[30].

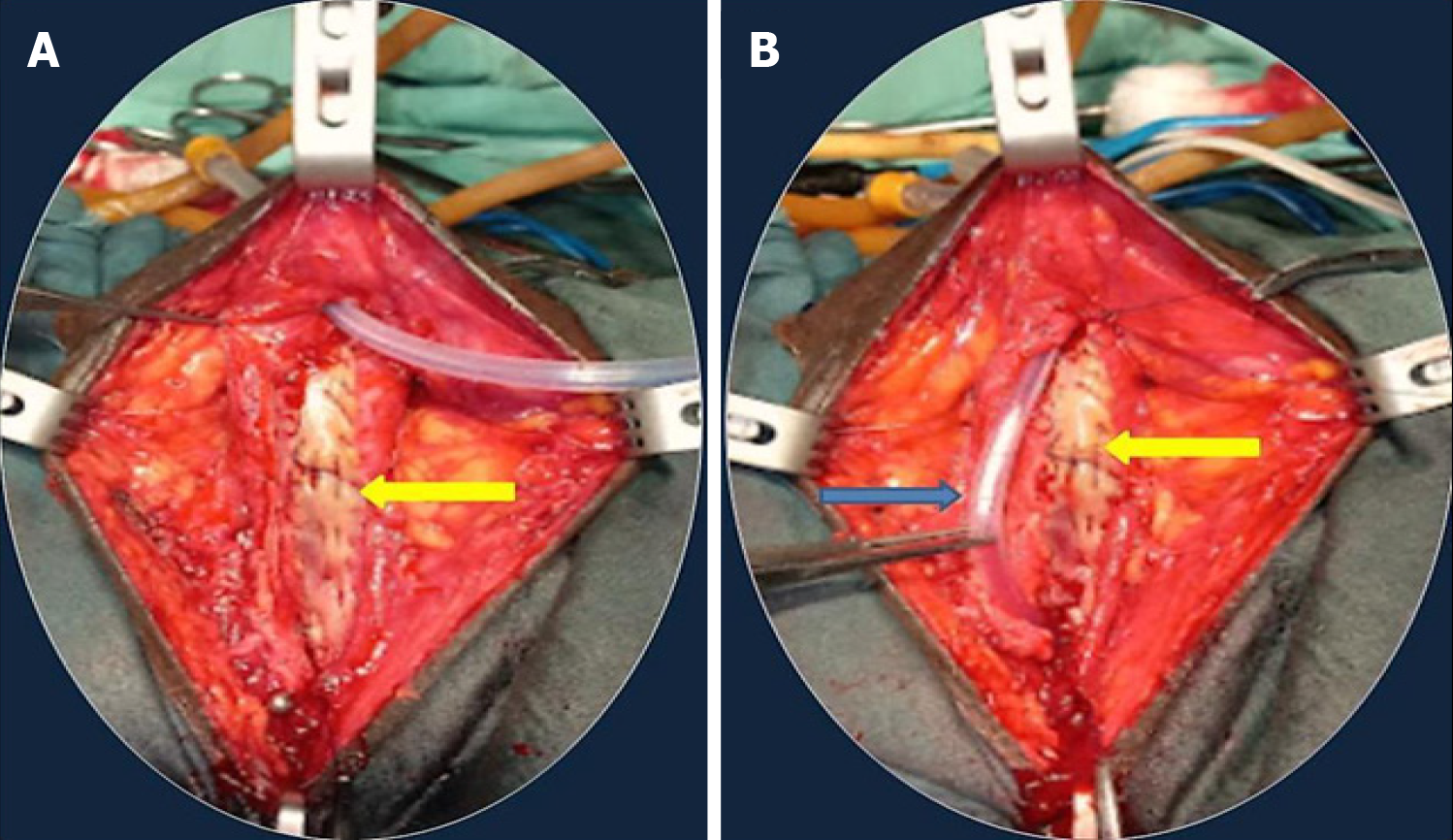

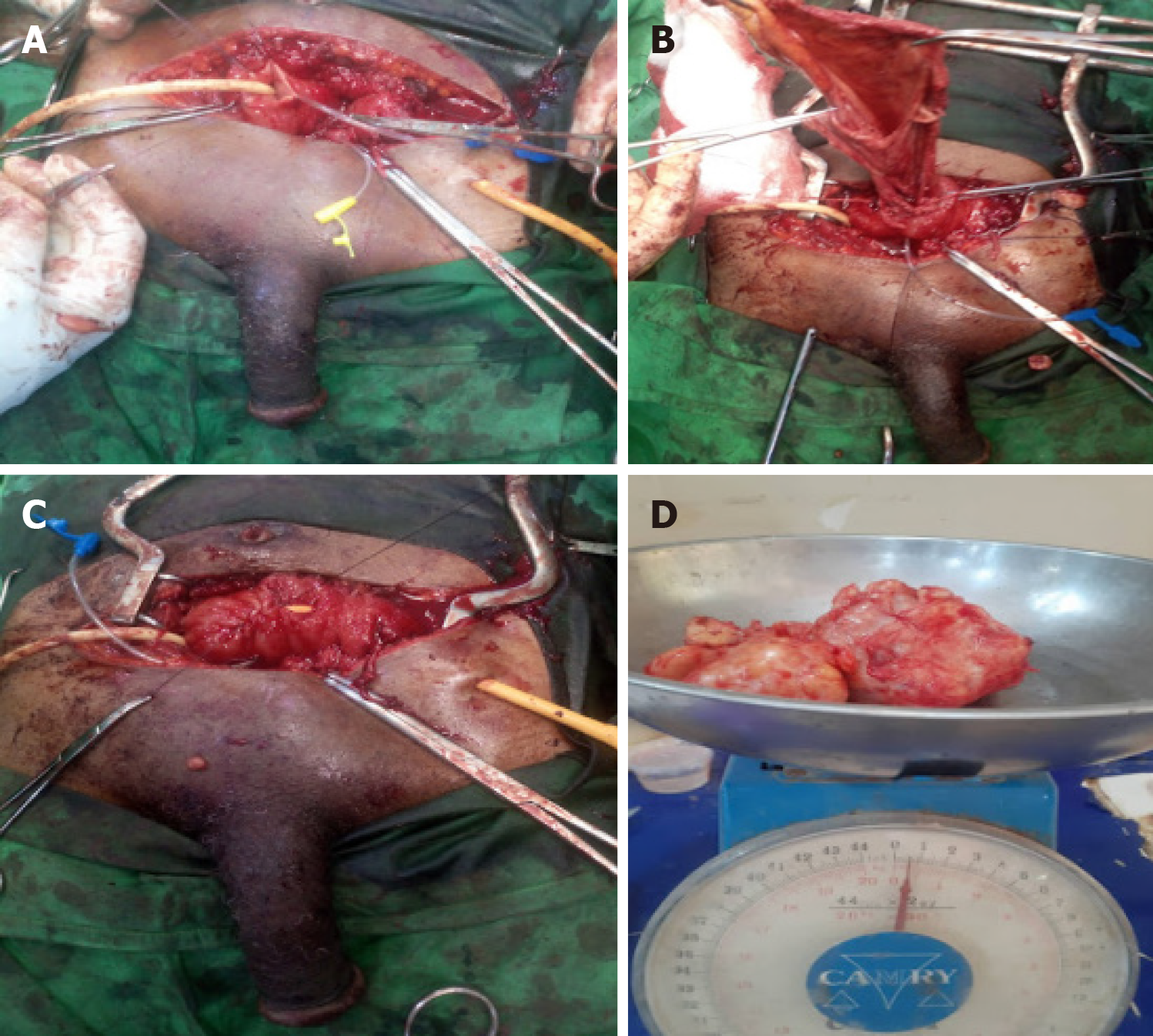

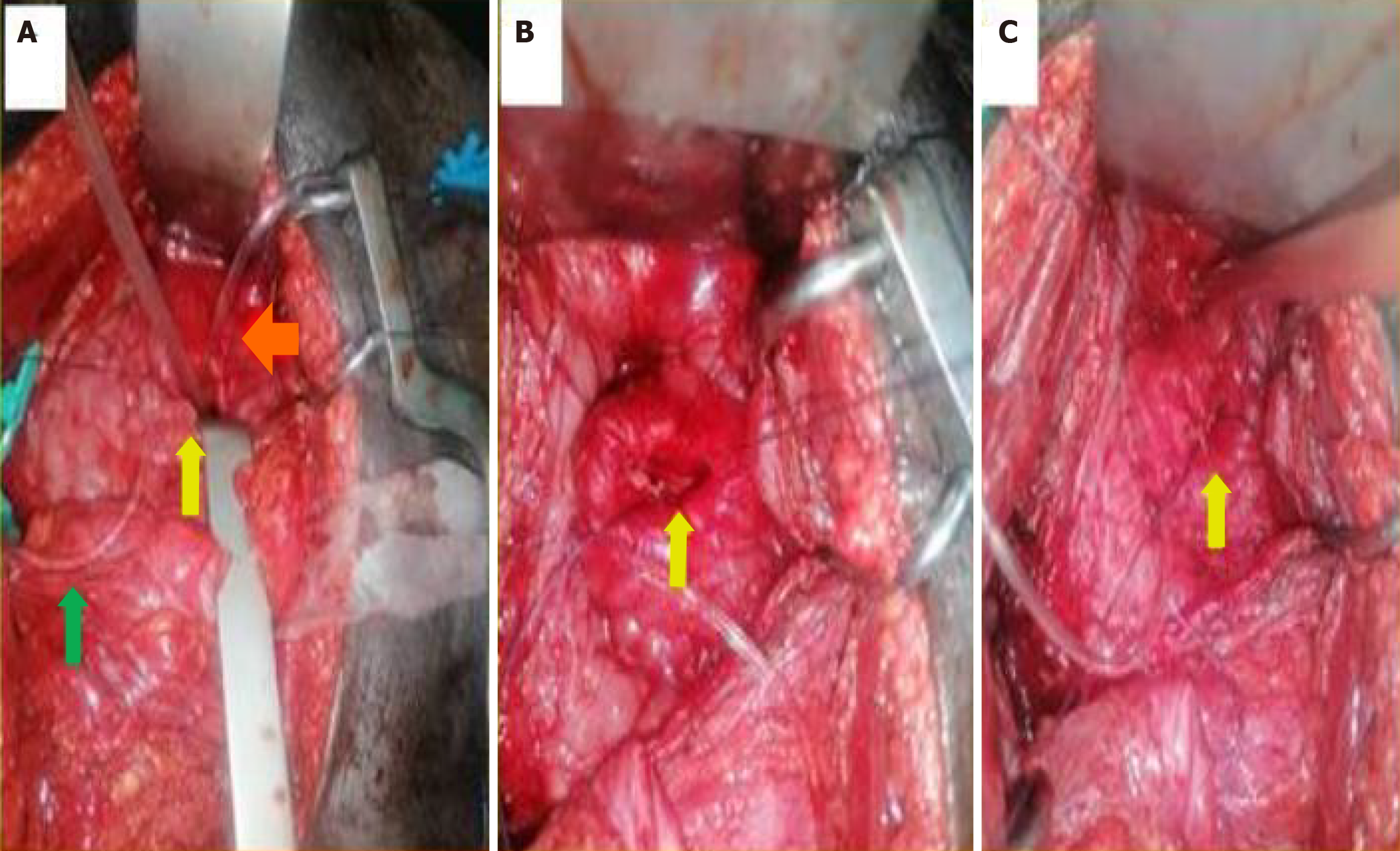

Surgical diverticulectomy is often curative and can be performed using various techniques, including open surgery, laparoscopic methods, or robotic assistance. Open diverticulectomy is commonly conducted through a transvesical approach (Figures 8 and 9). Generally, the bladder is accessed extraperitoneally via an infraumbilical midline or transverse incision, followed by careful development of the retropubic space. Ureteral stenting and meticulous dissection are crucial to avoid ureteral injury, as many bladder diverticula are located near the ureters (Figure 9A) or may adhere to them.

The transvesical approach, first described in 1906 by Hampton Young, involves creating an anterior wall cystotomy with proper retraction to visualize the diverticular neck (Figure 9B)[29]. For small diverticula without extravesical adhesions or inflammation, the diverticulum can be grasped at its base with an Allis clamp, pulled through the neck, and everted into the bladder. The mucosa of the diverticulum at the ostium is then circumferentially incised and excised, with the defect in the bladder wall closed using absorbable sutures in two layers (Figure 9C). The risk of inadvertently injuring surrounding structures is significant due to the blind pull technique. If eversion of the diverticulum is complicated by adhesions or inflammation, or if the diverticulum is too large for complete exposure during eversion, a submucosal excision may be performed[1]. In this case, the neck of the diverticulum is identified, mobilized, and sharply circumscribed with scissors or electrocautery. The plane between the diverticulum and its fibrous pseudocapsule is identified, and with circumferential traction on the neck edges using Allis clamps, both sharp and blunt dissection is performed to free the diverticulum from its pseudocapsule before detaching it. Typically, drainage of the potential space left by the pseudocapsule is unnecessary after the two-layer closure of the resulting defect.

For individuals with large diverticula and/or significant peridiverticular inflammation, a combined intravesical and extravesical approach may be required, as a purely transvesical approach may not be feasible[1]. Following an anterior cystotomy and circumferential incision of the diverticular neck, the surgeon’s finger can be introduced into the diverticulum to locate remaining parts, which may also be packed with moist gauze[29]. If mobile enough, the anterior aspect of the neck is brought into the operative field outside the bladder. Initially, the anterior part of the neck is dissected free of tissue, exposed, and incised extravesically. Then, the entire neck is circumferentially mobilized and transected, after which the diverticular wall is mobilized and dissected free of its attachments as described earlier. In some cases, it may be necessary to divide the ipsilateral superior vesical pedicle or extend the original cystotomy incision in a “T” fashion to facilitate exposure and delivery of the diverticulum[1]. This technique typically involves the complete removal of the diverticulum along with the fibrous pseudocapsule. In cases where the diverticulum closely adheres to surrounding vital structures, it may be necessary to leave parts of the fibrous pseudocapsule in place.

Minimally invasive techniques, including laparoscopy (Figures 10 and 11) and robotic-assisted diverticulectomy, have been implemented in surgical diverticulectomy[31,32]. Both intra- and extraperitoneal approaches have been described. Approaching the diverticulum extravesically, while simultaneously using intraoperative cystoscopic transillumination, can help in locating the diverticulum within the retroperitoneal tissues (Figure 10A-C)[33]. Several non-randomized case series suggest that the outcomes of these minimally invasive techniques are comparable to those of traditional open methods[34,35].

Complications arising from diverticula include stone formation, recurrent UTIs, malignancy, and upper urinary tract deterioration due to VUR or obstruction. These issues stem from urine stasis within the diverticula, leading to chronic inflammation.

One of the most serious complications following surgical diverticulectomy is injury to the ureter, either intramurally or at the pelvic level, which can occur particularly during the dissection of a large diverticulum. However, this injury can typically be prevented or at least detected early and repaired effectively through the placement of an ipsilateral ureteral stent.

For a partial transection of the ureter, primary repair using Vicryl 5-0 sutures combined with ureteral stenting is usually adequate. In cases of severe damage or complete transection of the distal third of the ureter, ureteric reimplantation-possibly with a psoas hitch-is required[1].

Additional complications can include hemorrhage, urinary fistulas, injury to the rectum or bowel, and pelvic abscesses. A less severe issue is leakage of urine from the bladder, which may resolve on its own if a Foley catheter is left in place for a few additional days, provided that the underlying obstruction has been addressed.

Approximately one-third of these lesions can be cured or significantly improved with TUR[29]. Open excision of the diverticulum is typically curative for the benign form (Figure 11), although it is crucial to address the underlying cause to prevent recurrence or the development of another diverticulum. The prognosis is generally poor for cases involving intradiverticular carcinoma, mainly due to delayed or challenging diagnoses and the risk of early extravesical disease extension[21]. However, there have been reports of relatively high five-year survival rates of around 70%, attributed in part to earlier diagnoses facilitated by advanced imaging techniques and a lower threshold for cystoscopy, along with prompt, aggressive surgical intervention[36].

The bladder diverticulum is a rare condition that can cause significant distress for those affected. In children, it primarily occurs as a developmental issue, while in adults, it often results from common urologic conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia and urethral stricture, among others. Diagnosing this condition can be challenging; however, a tailored clinical evaluation, combined with appropriate imaging investigations such as abdominal ultrasound, contrast radiography, and CT scans, can facilitate accurate diagnosis when necessary. These imaging techniques play a crucial role in management planning, helping to determine suitable treatment options and anticipate outcomes. Treatment should be individualized based on the underlying cause of the diverticulum, the extent of the condition, associated complications, available local resources, patient preferences, and the surgeon's experience. This is important because open, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted surgical approaches can yield relatively comparable outcomes when applied to well-selected patients.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all hospital staff and management for their support in creating an environment conducive to medical training, patient care, and research.

| 1. |

Rovner ES.

Bladder and female urethral diverticula. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. |

| 2. | Nguyen H, Cilento B. Bladder diverticula, urachal anomalies, and other uncommon anomalies of the bladder. In: Gearhart JP, Rink RC, Mouriquand PDE, editors. Pediatric Urology. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders, 2010: 416-424. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Blane CE, Zerin JM, Bloom DA. Bladder diverticula in children. Radiology. 1994;190:695-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Idrees MT, Alexander RE, Kum JB, Cheng L. The spectrum of histopathologic findings in vesical diverticulum: implications for pathogenesis and staging. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1223-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abou Zahr R, Chalhoub K, Ollaik F, Nohra J. Congenital Bladder Diverticulum in Adults: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Urol. 2018;2018:9748926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Garat JM, Angerri O, Caffaratti J, Moscatiello P, Villavicencio H. Primary congenital bladder diverticula in children. Urology. 2007;70:984-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boechat MI, Lebowitz RL. Diverticula of the bladder in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1978;7:22-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hebert KL, Martin AD. Management of Bladder Diverticula in Menkes Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Urology. 2015;86:162-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Burrows NP, Monk BE, Harrison JB, Pope FM. Giant bladder diverticulum in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type I causing outflow obstruction. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:109-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Melekos MD, Asbach HW, Barbalias GA. Vesical diverticula: etiology, diagnosis, tumorigenesis, and treatment. Analysis of 74 cases. Urology. 1987;30:453-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Raheem OA, Besharatian B, Hickey DP. Surgical management of bladder transitional cell carcinoma in a vesicular diverticulum: case report. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:E60-E64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gkalonaki I, Anastasakis M, Panteli C, Patoulias I. Hutch diverticulum: from embryology to clinical practice. Folia Med Cracov. 2022;62:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gerridzen RG, Futter NG. Ten-year review of vesical diverticula. Urology. 1982;20:33-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hernández J, Waguespack RL, Horton M, Rozanski TA. Acute urinary retention due to an iatrogenic bladder diverticulum. J Urol. 1997;158:1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chertin B, Prat O. Iatrogenic bladder diverticula following caesarean section. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1707-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhengqiang W, Yinglei W, Cheng L, Dongbing Z. One-stage laparoscopy combined with resectoscope in the treatment of huge bladder diverticulum, multiple stones in diverticulum, multiple stones in bladder and benign prostatic hyperplasia: A case report. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1036222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nabavizadeh R, Nabavizadeh B, Hampton LJ, Nabavizadeh A. Herniation of a urinary bladder diverticulum: diagnosis and management of a fluctuating inguinal mass. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016217947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Omari AH, Alghazo MA. Urinary bladder diverticulum as a content of femoral hernia: a case report and review of literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Britto MM, Yao HHI, Campbell N. Delayed diagnosis of spontaneous rupture of a congenital bladder diverticulum as a rare cause of an acute abdomen. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:E385-E387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Leahy O, Grummet J. Splash! The spontaneous rupture of a bladder diverticulum: a rare cause of an acute abdomen. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:792-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Clayman RV, Shahin S, Reddy P, Fraley EE. Transurethral treatment of bladder diverticula. Alternative to open diverticulectomy. Urology. 1984;23:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pieretti RV, Pieretti-Vanmarcke RV. Congenital bladder diverticula in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Akbulut S, Cakabay B, Sezgin A, Isen K, Senol A. Giant vesical diverticulum: a rare cause of defecation disturbance. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3957-3959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kumar S, Jayant K, Barapatra Y, Rani J, Agrawal S. Giant Urinary Bladder Diverticula presenting as Epigastric Mass and Dyspepsia. Nephrourol Mon. 2014;6:e18918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Favorito LA. Bladder diverticula with more than 5 cm increases the risk of acute urinary retention in BPH. Int Braz J Urol. 2018;44:662-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kong MX, Zhao X, Kheterpal E, Lee P, Taneja S, Lepor H, Melamed J, Deng FM. Histopathologic and clinical features of vesical diverticula. Urology. 2013;82:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pham KN, Jeldres C, Hefty T, Corman JM. Endoscopic Management of Bladder Diverticula. Rev Urol. 2016;18:114-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cermak S, Putman S. [Micturition Complaints in Men: One Symptom, Multiple Causes]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2018;107:593-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gil-Vernet JM. Bladder diverticulectomy. In: Graham SD, editor. Glenn’s Urologic Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1998: 205-209. |

| 30. | Yamaguchi K, Kotake T, Nishikawa Y, Yanagi S, Namiki T, Ito H. Transurethral treatment of bladder diverticulum. Urol Int. 1992;48:210-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Khonsari S, Lee DI, Basillote JB, McDougall EM, Clayman RV. Intraoperative catheter management during laparoscopic excision of a giant bladder diverticulum. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:47-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hora M, Eret V, Stránský P, Trávníček I, Dolejšová O, Chudáček Z, Petersson F, Hes O, Chłosta P. Laparoscopic urinary bladder diverticulectomy combined with photoselective vaporisation of the prostate. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2015;10:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Janardanan S, Nigam A, Moschonas D, Perry M, Patil K. Urinary Bladder Diverticulum: A Single-Center Experience in the Management of Refractory Lower Urinary Symptoms Using a Robotic Platform. Cureus. 2023;15:e42354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Myer EG, Wagner JR. Robotic assisted laparoscopic bladder diverticulectomy. J Urol. 2007;178:2406-10; discussion 2410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Porpiglia F, Tarabuzzi R, Cossu M, Vacca F, Terrone C, Fiori C, Scarpa RM. Is laparoscopic bladder diverticulectomy after transurethral resection of the prostate safe and effective? Comparison with open surgery. J Endourol. 2004;18:73-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Baniel J, Vishna T. Primary transitional cell carcinoma in vesical diverticula. Urology. 1997;50:697-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/