Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.107181

Revised: April 21, 2025

Accepted: June 10, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 227 Days and 9.7 Hours

The reference ranges for biochemical parameters can fluctuate due to factors like altitude, age, gender, and socioeconomic conditions. These values are crucial for interpreting laboratory data and guide clinical treatment decisions. Currently, there is no established set of reference intervals for cord blood biochemical para

To create cord blood biochemical parameters reference intervals specifically for Mumbai, India.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in an Indian tertiary care hospital. This study focused on healthy newborns with normal birth weight, born to pregnant mothers without health issues. Cord blood samples, approximately 2-3 mL in volume, were collected from 210 term neonates. These samples were divided into fluoride (glucose) and clot activator (serum) tubes and were subsequently analyzed in the institute's biochemical laboratory. The data obtained from the analysis was then subjected to statistical analysis. The result of the Shapiro-Wilk test suggested non-normality in the data distribution. Consequently, non-parametric statistics were utilized for analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test was utilized to compare parameter distributions among different factors, including the infant’s sex, delivery method, maternal age, and obstetric history. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

The following represent the median figures and central 95 percentile reference intervals for biochemical parameters in umbilical cord blood of newborns: Serum direct bilirubin = (0.1–0.55) mg/dL, indirect bilirubin = (0.64–2.26) mg/dL, total bilirubin = (0.62–3.14) mg/dL, creatinine = (0.27–0.76) mg/dL, sodium = (128.19–143.26) mmol/L, chloride = (100.19–111.68) mmol/L, potassium = (1.62–9.98) mmol/L and plasma glucose = (24.75–94.23) mg/dL. Statistically significant differences were observed in serum sodium, potassium, and plasma glucose levels when comparing delivery modes.

This is the pioneering study in which first time, the biochemical reference intervals in cord blood for newborns are established in western India. The values are applicable for newborns from this area. Larger study throughout the country is required.

Core Tip: The reference ranges for biochemical parameters can fluctuate due to factors like altitude, age, gender, and socioeconomic conditions. These values are crucial for interpreting laboratory data and guide clinical treatment decisions. Currently, there is no established set of reference intervals for cord blood biochemical parameters of newborns. This study seeks to create these reference intervals.

- Citation: Sabnis K, Ghanghurde S, Shukla A, Sukheja D, Rojekar MV. Towards improved neonatal care: Developing reference intervals for biochemical parameters in umbilical cord blood: An Indian study. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(4): 107181

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i4/107181.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.107181

A reference interval is defined as a range that, when applied to the population served by a laboratory, appropriately includes the majority of individuals who share similar characteristics with the reference group, while excluding others[1]. Reference intervals are among the most commonly utilized tools in clinical decision-making, aiding physicians in diagnosing medical conditions and identifying diseased individuals. Hence, it is essential for the laboratory community to dedicate sufficient resources to the proper establishment of these intervals. However, due to challenges in recruiting an adequate number of reference individuals, there is a scarcity of studies focused on reference intervals for biochemical analytes in neonates. As a result, existing reference intervals often reflect values derived from healthy adults. This study, therefore, aims to establish reference intervals for commonly tested biochemical analytes specifically in neonates.

To prevent misunderstanding, it is important to acknowledge that the term “normal” can carry various interpretations. Rather than using outdated terms like “normal values” or “normal ranges” as substitutes for reference range or reference intervals (RIs), it is advisable to use the more accurate and widely accepted terms “reference range” or “reference interval”[1]. These terms have been broadly adopted in medical practice to reduce ambiguity and promote clarity.

Interpretation of laboratory data is essential in patient management, including evaluating whether a patient’s results fall within the normal reference interval and determining suitability for clinical and vaccine trials. The application of RIs is central to these processes[2]. These RIs can vary due to several factors such as age, sex, race, geographical location, and dietary habits. Numerous studies worldwide have demonstrated age-related variations in biochemical parameters. Infants, in particular, show significant quantitative and qualitative differences in these parameters compared to older children and adults[3]. Therefore, it has been concluded that using adult reference ranges to assess pediatric blood samples is highly inappropriate.

Using reference intervals derived from a different geographical region or age group for a specific target population can lead to suboptimal patient management and inefficient resource utilization[4]. Furthermore, when individual laboratories establish their own RIs, discrepancies often arise in the resulting reference intervals that are not justified by factors affecting analysis or differences specific to population[5]. Recent studies have developed neonatal RIs for biochemical analytes based on local populations. In this context, our study aimed to establish reference intervals for common biochemical analytes—plasma glucose, serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and serum electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, and chloride—in term newborns from India.

The biochemical profile of neonates can be affected by various factors, including the mother’s lifestyle choices—such as smoking and alcohol consumption—and her medical history, including conditions like diabetes mellitus, eclampsia, and hypertension[6-9]. Furthermore, factors such as the mode of delivery, number of previous pregnancies, and obstetric and abortion history can also influence neonatal biochemical parameters. These types of variations in reference intervals—arising from geographical location, lifestyle, and other aforementioned factors—highlight the critical need to establish reference intervals that take such variations into account.

Umbilical cord blood collection (UCBC) is a safe and non-invasive method. Neither mother nor fetus get harmed in this. Apart from minor risks associated with delayed cord clamping and cord milking—which may influence certain biochemical parameters[10]—UCBC remains a relatively simple and safe technique for obtaining blood samples. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that UCBC offers higher sensitivity and accuracy in predicting disease outcomes compared to peripheral venous blood collection, supporting its reliability as a predictive tool[11]. Therefore, for the present study, the cord blood collection method was employed. This study aimed to establish reference intervals for cord blood biochemical parameters in a tertiary care hospital and teaching institute in western India.

A cross-sectional study was conducted after due approval from the ICEC in a tertiary care hospital attached to a medical college in western part of Maharashtra, India. The study was conducted from October 2022 to December 2022. Study participants were recruited from mothers coming to the hospital to get delivery service.

Cross-sectional study was carried out among healthy, term neonates (37 to 42 weeks of gestational age) with normal birth weight, born to apparently healthy mothers and receiving delivery services at the institution. Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guideline C28-A3 recommended at least 120 samples per group for estimating the 95% reference interval[12]. Strategy used was ‘a priori selection’ in which eligible mothers were selected in the age group of 18 to 45 years. Total 210 subjects were recruited in this study.

Mothers were excluded if they had a medical disorder like infectious diseases (Hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency virus, Syphilis), chronic diseases (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus), complications during pregnancy (preeclampsia) or parturition, psychiatric illness, or addictions (e.g., smoking, excessive alcohol intake). Exclusion was established by a combination of diagnostic tests— such as neonatal screening tests (Perkin Elmer system), thyrotropin, Biotinidase, immunoreactive Trypsinogen determination, results from ultrasound, and clinical history.

The inclusion criteria of mothers were hemoglobin 12.0 g/dL or higher[13], and an inter-pregnancy interval of 18 months or longer, as defined by the World Health Organization[14]. Furthermore, posteriori selection strategy was used to select eligible neonates—i.e., with a gestational age of 37 to 42 weeks and with a 5th-minute Apgar score of 7 or greater. Neonates with respiratory distress, meconium aspiration, apparent congenital anomalies (e.g., Down syndrome, cystic fibrosis, neural tube defects, or congenital hypothyroidism), or true knots of umbilical cords were not included in the study.

Prior to initiating data collection, all involved professionals were briefed on the study objectives, the criteria for participant selection, data confidentiality and safety precautions related to collection, transport, and storage of cord blood samples. To gather demographic details and a brief medical history, a structured questionnaire was administered to mothers who met the inclusion criteria and provided their consent to participate.

Due to the physically demanding nature of childbearing, the attending midwives obtained informed written consent in line with the standards set by the Helsinki Declaration and assisted the consenting women to complete the questionnaire before being admitted to the labor room. Cord blood sampling was performed only after the placenta was fully delivered and separated from the mother, and the umbilical cord was cut following clamping. The cord was clamped within one minute after birth, and 4-5 mL of blood was drawn from the umbilical vein using a sterile needle and syringe. The operation room (OR) nurse collected the samples into vacutainers (BD vacutainers)— one containing sodium fluoride for blood glucose measurement, and plain vacutainers for analyzing serum electrolytes, bilirubin, and creatinine. The samples were sent immediately to the biochemistry laboratory for evaluation.

As per the protocol of routine prenatal care, participants of the study were tested for retro viral disease via rapid diagnostic tests, Australian antigen test and Syphilis using venereal disease research laboratory test. Ultrasonography was done to rule out any gross congenital defects.

Both external and internal quality control measures were conducted in a timely manner. Internal quality control was performed daily—prior to the test run, intermittently during the run, and upon completion. Cord blood sample collection was carried out by experienced OR nurses in accordance with established guidelines for cord blood collection. All procedures were performed in strict adherence to the respective standard operating procedures.

Over the course of 3 months, 210 blood samples were collected by operation theater staff from umbilical vein of the expelled placenta, into appropriate vacutainers (gray for estimating sugar and plain vacutainer for serological parameters) and sent to laboratory immediately for analysis. Namely plasma glucose, serum creatinine, serum ele

After meticulously reviewing all data collected from the questionnaire and laboratory results for completeness and accuracy, we inputted the data into MS Excel and performed further analysis using IBM® SPSS® Statistics. As per the CLSI recommendation, we calculated the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles for biochemical parameters in 210 neonates[10], To com

Data were assessed for outliers using the sorting method, and identified outliers were removed using the trimming method. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to check whether data is normally distributed or not.

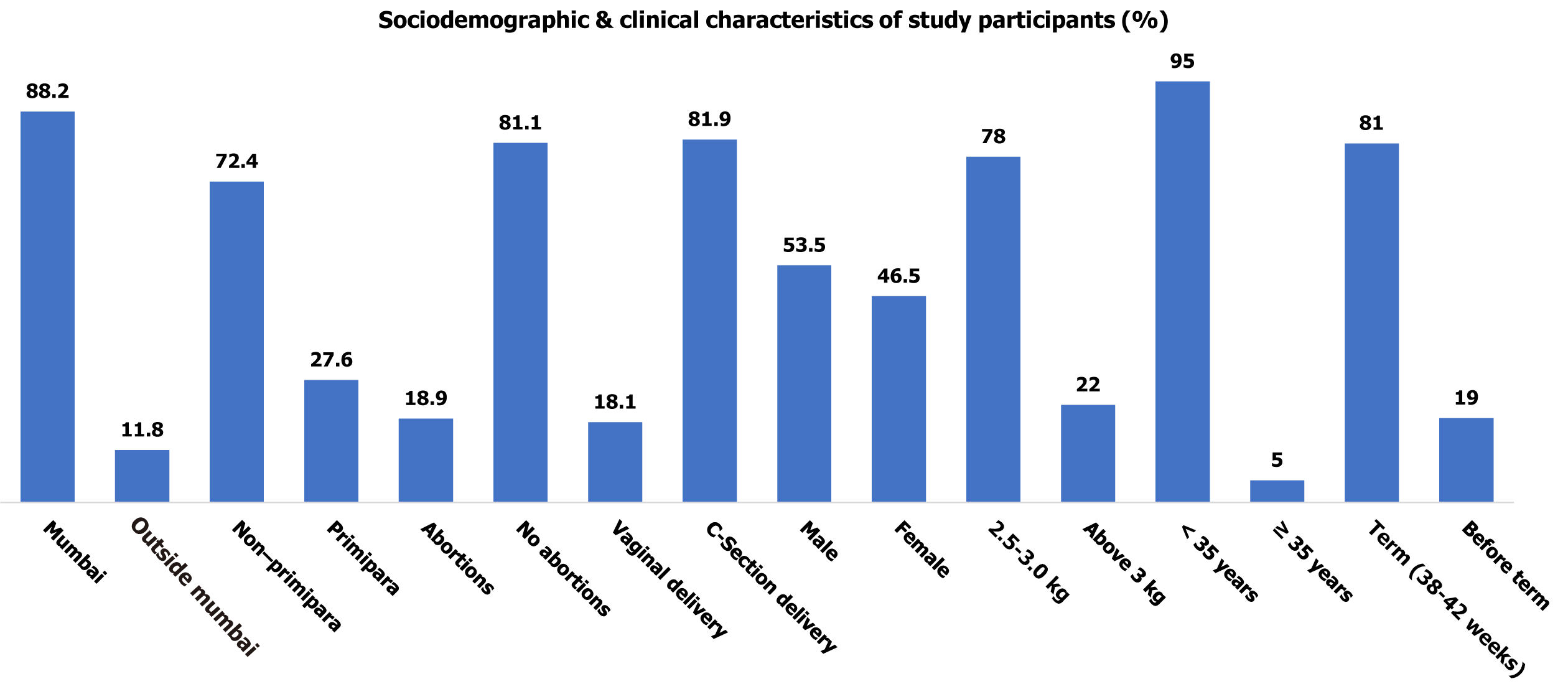

210 full-term, healthy neonates were enrolled in the study, with 112 (53.5%) males and 98 (46.5%) females. Approximately 81.3% of the mothers were in the age group of 18–30 years, and 12% resided outside the metropolitan area. Among the 210 mothers, 27.56% were primiparous. The relatively high proportion of caesarean sections observed in the study may be attributed to a substantial number of referrals from peripheral centers, as the study site serves as the only public-sector tertiary care hospital within a 50-kilometer radius. Complete sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Information | Number of subjects | Percentage | |

| Resident of | Mumbai | 185 | 88.2 |

| Outside Mumbai | 25 | 11.8 | |

| Parity | Non–primipara | 152 | 72.4 |

| Primipara | 58 | 27.6 | |

| Obstetric history1 | Abortions | 40 | 18.9 |

| No abortions | 170 | 81.1 | |

| Delivery mode | Vaginal delivery | 38 | 18.1 |

| C-Section delivery2 | 172 | 81.9 | |

| Sex of neonate | Male | 112 | 53.5 |

| Female | 98 | 46.5 | |

| Weight of neonate | 2.5–3.0 kg | 164 | 78 |

| Above 3 kg | 46 | 22 | |

| Maternal age | < 35 years | 199 | 95 |

| > or = 35 years | 11 | 5 | |

| Gestational age of infant | Term (38-42 weeks) | 170 | 81 |

| Before term | 40 | 19 | |

No statistically significant differences in any of the biochemical parameters were found with respect to the mother's obstetric history (primiparous vs multiparous) or the infant's sex (male vs female) (P > 0.05). An independent Mann–Whitney U test revealed a statistically significant difference in the measured parameters between the different delivery modes (P < 0.05) (As displayed in Table 2).

| Parameters | P value | Median | ||

| By sex | Mode of delivery | Obstetric history | ||

| Serum bilirubin (T) | 0.9278 | 0.1305 | 0.1800 | 1.9 |

| Serum bilirubin (D) | 0.5564 | 0.2016 | 0.9971 | 0.3 |

| Serum bilirubin (I) | 0.3965 | 0.1461 | 0.5466 | 1.4 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.2804 | 0.7301 | 0.5292 | 0.56 |

| Serum sodium | 0.4030 | 0.0128 | 0.7638 | 136.3 |

| Serum potassium | 0.5892 | 0.0411 | 0.7086 | 5.085 |

| Serum chloride | 0.7847 | 0.1800 | 0.6612 | 106 |

| Plasma glucose | 0.8293 | 0.0039 | 0.8404 | 57.2 |

A comprehensive summary of the upper and lower reference intervals for biochemical analytes in neonatal umbilical cord blood has been provided in Table 3. Except serum sodium, potassium and plasma glucose, there was no statistical significance observed in case of mode of delivery.

| Parameter | Sex | N | Median | Mean | Max | Min | Reference interval | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| Serum bilirubin (T) | Male | 112 | 1.85 | 1.824 | 3.2 | 0.25 | 0.509 | 3.139 |

| Female | 98 | 1.8 | 1.834 | 3.17 | 0.3 | 0.687 | 2.981 | |

| Combined | 210 | 1.9 | 1.879 | 3.24 | 0.25 | 0.618 | 3.14 | |

| Serum bilirubin (D) | Male | 112 | 0.3 | 0.318 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.095 | 0.541 |

| Female | 98 | 0.3 | 0.326 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.095 | 0.565 | |

| Combined | 210 | 0.3 | 0.354 | 1.22 | 0.1 | 0.097 | 0.55 | |

| Serum bilirubin (I) | Male | 112 | 1.16 | 1.159 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.7276 | 2.036 |

| Female | 98 | 1.2 | 1.334 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.7234 | 1.944 | |

| Combined | 210 | 1.4 | 1.453 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 0.644 | 2.262 | |

| Serum creatinine | Male | 112 | 0.55 | 0.492 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.248 | 0.736 |

| Female | 98 | 0.545 | 0.515 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 0.282 | 0.748 | |

| Combined | 210 | 0.56 | 0.511 | 0.72 | 0.31 | 0.2677 | 0.755 | |

| Serum sodium | Male | 112 | 137 | 136.075 | 142.3 | 137 | 129.392 | 142.76 |

| Female | 98 | 136.2 | 135.51 | 142.6 | 124 | 127.03 | 143.99 | |

| Combined | 210 | 136.3 | 135.72 | 142.6 | 124 | 128.19 | 143.26 | |

| Serum potassium | Male | 112 | 5.31 | 5.77 | 9.89 | 3.9 | 2.16 | 9.37 |

| Female | 98 | 4.955 | 5.592 | 9.6 | 3.9 | 1.952 | 9.233 | |

| Combined | 210 | 5.085 | 5.797 | 15.41 | 3.9 | 1.62 | 9.98 | |

| Serum chloride | Male | 112 | 106.1 | 105.94 | 113.3 | 97 | 99.65 | 112.23 |

| Female | 98 | 106.65 | 106.08 | 111 | 97.8 | 100.65 | 111.52 | |

| Combined | 210 | 106 | 105.94 | 113.3 | 97 | 100.19 | 111.68 | |

| Plasma glucose | Male | 112 | 55.6 | 59.74 | 91.8 | 33.4 | 17.85 | 101.62 |

| Female | 98 | 59 | 59.073 | 94.8 | 42.1 | 34.742 | 83.4036 | |

| Combined | 210 | 57.2 | 59.49 | 94.8 | 31.6 | 24.75 | 94.23 | |

The combined median values and central 95th percentile reference intervals for cord blood analytes are presented in Table 3. We also have included a comparative analysis between the existing reference intervals of cord blood and those provided by Sysmex for neonates aged 0–24 hours, along with reference data from previously published studies. As most previous studies have reported their findings as mean ± SD, the comparisons in the present study were performed accordingly and are presented in a similar format in Table 4.

| Parameter | PVB[19] | Current Study | China[17] | Korea[16] | ||

| RI | RI | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.33–0.71 | 0.1-0.55 | 0.3 | 0.354 | NA | NA |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | NA | 0.64-2.262 | 1.4 | 1.453 | NA | NA |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.19–16.6 | 0.62-3.14 | 1.9 | 1.879 | NA | 0.5 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.32–0.92 | 0.27-0.76 | 0.56 | 0.511 | NA | 0.38 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 102–111 | 100.19-111.68 | 106 | 105.94 | 101 | NA |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.7–5.9 | 1.62–9.98 | 5.085 | 5.797 | 4.05 | NA |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 133–146 | 128.19-143.26 | 136.3 | 135.72 | 135 | NA |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 30–60 | 24.75–94.23 | 57.2 | 59.49 | NA | 96.5 |

A complete summary of sex specific upper and lower margins for the biochemical parameters’ reference ranges of from umbilical cord blood is provided in Table 3. The combined median, mean and central 95 percentiles reference interval of cord blood parameters are also shown in Table 3.

Establishing reference intervals for neonates, infants, and children is demanding task as their physiological attributes undergo constant changes during their development[15]. During the initial hours and days after birth, there are notable alterations in the blood, particularly in newborns[16]. Furthermore, the majority of research studies have been performed on hospitalized individuals instead of healthy neonates, resulting in limited evidence for establishing reference intervals for neonates[15]. Consequently, it is crucial to establish these reference intervals specifically for healthy neonates.

There was no previously reported statistical significance in the mode of delivery, sex of the infant or the obstetrics history for serum creatinine which is in accordance with the study conducted in Korea[16].

There was no statistical significance in the mode of delivery for serum sodium, potassium and chloride levels which is in accordance to the result obtained from a study conducted in China[17], it is important to note that this study describes not cord blood parameters but postnatal (day 1-3) levels of concerned parameters. Although a statistical significance was obtained in case of mode of delivery for serum levels of potassium in this study.

This study also found narrowed reference interval for serum levels of total bilirubin, sodium whereas widened interval is seen in serum direct bilirubin, chloride, potassium and plasma glucose.

The high glucose levels in the cord blood of Indian neonates might be associated with the higher prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus among pregnant women in India. Another reason might be the lower insulin sensitivity and higher fat mass in Indian babies which could lead to higher glucose levels. A higher glucose level in Korean neonates may be associated with their higher levels of insulin resistance and lower insulin secretion capacity in comparison to Indian neonates[18].

A higher prevalence of maternal anemia in the Indian population can lead to fetal hypoxia and acidosis which may be associated with the high levels of potassium in the fetal bloodstream. Stress due to labor may also be a cause for these high levels. After comparing the two studies, it was realized that Indian cord blood has elevated potassium levels as compared to Chinese cord blood. This may be associated with differences in fetal-maternal circulation as well as difference in maternal nutrition. The high level of potassium due to hemolysis is ruled out as hemolysis would result in evident elevation of other electrolytes as well.

Lowered serum sodium in Indian cord blood in comparison to peripheral venous blood may be due to high prevalence of malnutrition. Another cause may be difference in environmental factors such as temperature and climate. Indian samples showed higher sodium levels than Chinese which may be associated with dietary preferences in India i.e. higher salt intake.

Deviations seen in Indian levels of bilirubin maybe associated with different dietary preferences, different environmental factors, and genetic variabilities.

Establishing reference intervals is essential for interpreting biochemical variations in neonatal care. However, to date, there are only few published reference intervals for cord blood biochemical markers in neonates from India. The current study provides various statistical parameters (i.e., Reference interval, mean, median etc.), that enables the reader to develop a comprehensive understanding of the available literature. Although the study was conducted on a smaller population in Mumbai, its applicability is broad due to the diversity of the participants' backgrounds. Nevertheless, confirmation of the results is necessary through larger sample sizes from different regions of the country to ensure wider utilization.

A key limitation of this study is the absence of stratified reference intervals based on variables such as ethnicity, gestational age, and mode of delivery. Ideally, separate reference ranges accounting for these factors would enhance clinical applicability; however, this study provides generalized intervals without such subgroup differentiation.

The authors would like to acknowledge study participants for their kind collaboration, Rajiv Gandhi Medical College and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Hospital for the material support, labor room and operation theatre nurses, and lab technicians of the hospital for the unreserved support.

| 1. | Ceriotti F. Prerequisites for use of common reference intervals. Clin Biochem Rev. 2007;28:115-121. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Zeh CE, Odhiambo CO, Mills LA. Laboratory Reference Intervals in Africa. In: Moschandreou TE, Editors. Blood Cell - An Overview of Studies in Hematology. Intech Open, 2012. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Proytcheva MA. Issues in neonatal cellular analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:560-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Berg J, Lane V. Pathology Harmony; a pragmatic and scientific approach to unfounded variation in the clinical laboratory. Ann Clin Biochem. 2011;48:195-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rifai N, Chiu R, Young I, Burnham C, Wittwer C. Tietz textbook of laboratory medicine. 7th ed. Missouri: Elsevier, 2023: 167-9. |

| 6. | Zawiejska A, Wender-Ozegowska E, Radzicka S, Brazert J. Maternal hyperglycemia according to IADPSG criteria as a predictor of perinatal complications in women with gestational diabetes: a retrospective observational study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:1526-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aydin BK, Yasa B, Moore JP, Yasa C, Poyrazoglu S, Bas F, Coban A, Darendeliler F, Winters SJ. Impact of Smoking, Obesity and Maternal Diabetes on SHBG Levels in Newborns. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2022;130:335-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Rawi NH, Al-Saeed AH, Al-Ani NK, Al-Hadithi TS. Influence of maternal lifestyle on neonatal creatinine levels. J Clin Neonatol. 2018;7:219-222. |

| 9. | de Ruyter H, Aitokari L, Lahti S, Riekki H, Huhtala H, Lakka T, Laivuori H, Kurppa K. Maternal gestational hypertension, smoking and pre-eclampsia are associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in overweight offspring. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103:1183-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Murali M, Sethuraman G, Vasudevan J, Umadevi L, Devi U. Delayed cord clamping versus cord milking in vigorous neonates ≥35 weeks gestation born via cesarean: A Randomized clinical trial. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2023;16:597-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sabnis K, Ghanghurde S, Shukla A, Sukheja D, Rojekar MV. An Indian perspective for umbilical cord blood haematological parameters reference interval. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23:287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Boyd JC. Defining laboratory reference values and decision limits: populations, intervals, and interpretations. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:83-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | WHO. Haemoglobin concentration for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2011. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1. |

| 14. | WHO. Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing. Geneva, Switzerland. June 13-15, 2005; 1-45. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-07.1. |

| 15. | Siest G. Study of reference values and biological variation: a necessity and a model for Preventive Medicine Centers. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42:810-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Choi SJ, Lee S, Lee B, Jang JY, Cho J, Uh Y. Comparison of neonatal reference intervals for 23 biochemical analytes in the cord blood-A single center study in South Korea. Turk J Pediatr. 2019;61:337-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang K, Zhu X, Zhou Q, Xu J. Reference intervals for 26 common biochemical analytes in term neonates in Jilin Province, China. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Salis ER, Reith DM, Wheeler BJ, Broadbent RS, Medlicott NJ. Hyperglycaemic preterm neonates exhibit insulin resistance and low insulin production. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1:e000160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rifai N, Chiu R, Young I, Burnham C, Wittwer C. Tietz textbook of laboratory medicine. 7th ed. Missouri: Elsevier, 2023: 1392-1467. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/