Published online Jun 9, 2024. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v13.i2.91275

Revised: April 21, 2024

Accepted: May 14, 2024

Published online: June 9, 2024

Processing time: 164 Days and 6.2 Hours

The technological evolution of bronchoscopy has led to the widespread adoption of flexible techniques and their use for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Currently, there is an active debate regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of rigid vs flexible bronchoscopy in the treatment of foreign body aspiration.

To evaluate our experience with tracheobronchial foreign body extraction using flexible bronchoscopy and provide a literature overview.

This was a single-centre retrospective study. Twenty-four patients were enrolled between January 2017 and January 2023. Medical records of patients aged below 18 years who were admitted to authors’ affiliated institution with a suspected diagnosis of foreign body aspiration were collected from hospital’s database to Microsoft Excel 2019. Data were analysed using MedCalc Statistical Software.

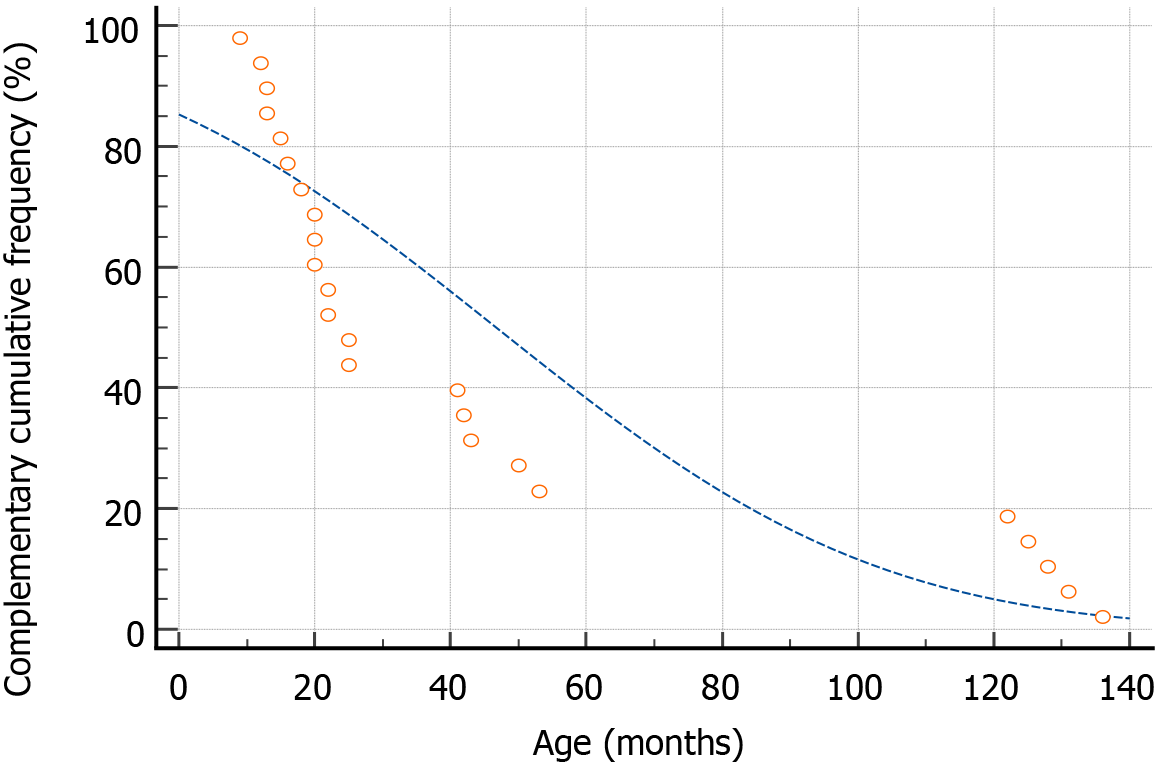

Patient ages varied from 9 months to 11 years. The median age was 23.5 months, 95% confidence interval (CI) 19.49-44.77. We observed age clustering in children with foreign body aspiration at our institution with three age subgroups: (1) 0-25 months; (2) 40-60 months; and (3) 120-140 months. We expectancy of an organic tracheobronchial foreign body was significantly higher in 0-25 months subgroup than that in older ones when subgroups 40-60 and 120-140 months were combined together (odds ratio = 10.0, 95%CI: 1.44-29.26, P = 0.0197). Successful foreign body extraction was performed in all cases. Conversion to a rigid bronchoscope was not required in any of the cases. No major complications (massive bleeding, tracheobronchial tree perforation, or asphyxia) were observed.

Flexible bronchoscopy is an effective and safe method for tracheobronchial foreign body extraction in children.

Core Tip: Foreign body aspiration is a well-known paediatric emergency issue, with a peak incidence at the age of 1-2 years. According to guidelines, rigid bronchoscopy remains the most widespread and acceptable treatment option for foreign body aspiration, while the role of flexible bronchoscopy is mainly limited to diagnostic purposes. A growing body of research has confirmed the safety and efficacy of flexible bronchoscopy as a therapeutic option. Literature data and our data indicate that flexible bronchoscopy may be considered a competitive alternative to rigid techniques, especially in relation to the distal tracheobronchial tree in young children.

- Citation: Sautin A, Marakhouski K, Pataleta A, Sanfirau K. Flexible bronchoscopy for foreign body aspiration in children: A single-centre experience. World J Clin Pediatr 2024; 13(2): 91275

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v13/i2/91275.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v13.i2.91275

A known history of paediatric therapeutic bronchoscopy began during the first half of the 20th century. This was associated with the development and usage of appropriate equipment-rigid bronchoscopes, prototype of which was developed in 1904 by famous American otorhinolaryngologist[1]. One of the first documented cases of tracheobronchial foreign body extraction via bronchoscopy in children was the extraction of chestnut parts from the youngest described patient, at 13 months of age, by Dr Hill[2], which was described in an article published in 1912. Earlier, in 1911, the “father of bronchoscopy”, published a series of 19 cases of foreign body extractions from the tracheobronchial tree in children aged 14 months to 7 years[2].

The equipment and personal experience improved over time and the procedure ceased to be exceptional. For example, 75 foreign bodies of the tracheobronchial tree in children aged ≥ 6 months were extracted via rigid technique by Burrington and Cotton[3] over a 5-year period in their late 60 s.

A new era of bronchoscopy began with the development of the flexible fibreoptic bronchoscope in 1967 by the Japanese doctor[1]. The use of flexible fibreoptic bronchoscopes for foreign body extraction was limited to single cases in adults and experimental animal research. Six out of seven successful cases of tracheobronchial foreign body extraction via flexible bronchoscope in adults were described in 1977[4] and 267 out of 300 (89%) were described in 1978[5].

In contrast to adults, the use of flexible bronchoscopy in children, especially therapeutic flexible bronchoscopy, is limited by several factors. The main of which is the small diameter of the airways and, therefore, the need for appropriate small-diameter devices. The first flexible bronchoscope made was about 6 mm in diameter which is comparable to the diameter of the trachea of a one-year-old child, not to mention the bronchi. At the end of 1978, Olympus Corporation developed a prototype bronchoscope with a 3.5 mm outer diameter and 1.2 mm working channel (BF3C4). The only diagnostic capabilities of which were described by Wood and Sherman[6], who performed 211 procedures in children ranging in age from newborns weighing 840 g to 14-year-old patients. In the same article, published in 1980, the following statement was found: “Most authorities suggest that flexible bronchoscopy cannot (or should not) be performed on children younger than about ten years”, reflecting the dominant opinion of the medical community of that time[6]. Thereafter, the first ultrathin bronchoscope equipped a 2.8 mm insertion tube outer diameter and 1.2 mm working channel was introduced in 2004 (Olympus BF-XP60)[7]. However, even nowadays, paediatric flexible bronchoscopy remains an exclusive add-on to endoscopy, with a unique pathology requiring special equipment and a long educational process.

For a long time, the main indication for bronchoscopy in children was foreign body aspiration. Currently, this remains the primary indication for rigid bronchoscopy in children. Data available from the United States showed that the frequency of choking injuries increased; there were 26 cases per 100000 patients aged 0-19 years for the period 2011-2016, compared with 19 cases per 100000 for the period 2005-2010[8]. The peak incidence of foreign body aspiration is noted at the age of 1-2 years[9-11]. Younger children are at special risk; patients aged below 5 years accounted for 73% of nonfatal injuries and 75% of choking fatalities[8]. The foreign body aspiration-related mortality rate is 1% in children aged from 1 to 15 years and up to 4% in infants, according to Health reports by the Federal Government of Germany[12].

According to current guidelines, removal of the airway foreign body should be performed using rigid bronchoscopy, while flexible bronchoscopy is considered only an auxiliary tool intended mainly for diagnostic purposes (pre- and postoperative examinations)[13,14]. However, flexible bronchoscopy is a well-known, safe, and widely accepted procedure involving several therapeutic modalities.

We hypothesized that this adherence to rigid method may be explained by historical circumstances and accumulated experience of medical community, as well as the lack of better alternatives in the past due to technical limitations of flexible equipment. In this study we aimed to evaluate our experience with tracheobronchial foreign body extraction using flexible bronchoscopy and provide a literature review.

This was a single centre, retrospective study. Twenty-four patients were enrolled in the study over a 5-year period from January 2017 to January 2023 (Table 1). Medical records of patients aged below 18 years were collected from patients who were admitted to the authors’ affiliated national paediatric surgery centre with a suspected diagnosis of foreign body aspiration. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Republican Scientific and Practical Centre of Paediatric Surgery (IRB No. 8.0). Date: 20/03/2023).

| Patient | Age (months) | FB localization | Distal end outer diameter of bronchoscope (mm) | Endoscopic instrument | Type of anaesthesia (LMA/ET) |

| 1 | 53 | Right main bronchus | 4.2 | Retrieval basket | ET, extraction with extubation |

| 2 | 13 | Left main bronchus | 3.1 | Tripod type forceps | ET, through the tube |

| 3 | 41 | Right main bronchus | 4.2 | Alligator jaw forceps | LMA |

| 4 | 122 | Intermediate bronchus | 3.1 | Rat tooth forceps | ET, extraction with extubation |

| 5 | 25 | Left main bronchus | 3.1 | Retrieval basket | LMA |

| 6 | 22 | Intermediate bronchus | 3.1 | Retrieval basket | ET, through the tube |

| 7 | 136 | Right lower lobe bronchus | 4.2 | N/D | LMA |

| 8 | 125 | Right main bronchus | 6.2 | Tripod type forceps | LMA |

| 9 | 16 | Left main bronchus | 3.1 with switching to 4.2 | Rat tooth forceps | LMA |

| 10 | 42 | Intermediate bronchus | 6.2 | Alligator jaw forceps | LMA |

| 11 | 25 | Right upper lobe bronchus | 3.1 with switching to 4.2 mm | Rat tooth forceps + retrieval net | LMA |

| 12 | 50 | Left lower lobe bronchus | 3.1 | Rat tooth forceps | LMA |

| 13 | 20 | Right lower lobe bronchus | 3.1 | Retrieval basket | LMA |

| 14 | 13 | Left main bronchus | 3.1 | N/D | LMA |

| 15 | 20 | Left lower lobe bronchus | 3.1 | Tripod type forceps + retrieval basket | ET, through the tube |

| 16 | 43 | Right upper lobe + lower lobe bronchi | 3.1 | Retrieval basket | ET, through the tube |

| 17 | 18 | Right main bronchus | 3.1 | Tripod type forceps | ET, extraction with extubation |

| 18 | 128 | Right lower lobe bronchus | 4.2 | Retrieval net | ET, extraction with extubation |

| 19 | 22 | Right lower lobe bronchus | 4.2 | Tripod type forceps + retrieval basket | ET, through the tube |

| 20 | 131 | Right main bronchus | 6.2 | N/D | LMA |

| 21 | 20 | Right main bronchus | 3.1 | Retrieval basket | LMA |

| 22 | 15 | Left main bronchus | 3.1 | Retrieval basket | LMA |

| 23 | 9 | Right upper lobe bronchus | 3.9 | Alligator jaw forceps | ET, through the tube |

| 24 | 12 | Right main bronchus | 3.1 | Snare | ET, extraction with extubation |

To extract the vast majority of foreign bodies, bronchoscopes BF-XP190 (distal end outer diameter 3.1 mm; instrument channel 1.2 mm) and BF-P190 (distal end outer diameter 4.2 mm; instrument channel 2.0 mm) were used; one foreign body was extracted using portable endoscope MAF-GM2 (distal end outer diameter 3.9 mm; instrument channel 1.5 mm) and three more using BF-1TH190 (distal end outer diameter 6.2 mm; instrument channel 2.8 mm). All the endoscopes were manufactured by Olympus Corporation (Tokyo, Japan).

As a working instrument, we used endoscopic grips, such as a retrieval basket, tripod type, forceps, a retrieval net, alligator jaw forceps, rat tooth forceps, and a snare, depending on the type of foreign body and operator’s experience. Three experts in gastrointestinal endoscopy (including gastrointestinal foreign body extraction) and bronchoscopy performed the extractions. The extraction was performed under general anaesthesia using artificial airways with a laryngeal mask or an endotracheal tube, under the supervision of a competent anaesthesiologist. Notably, the endoscope should be at least 1 mm thinner than the inner diameter of the endotracheal tube to avoid tube dislocation and equipment damage[13]. Furthermore, the inner endotracheal tube diameter can be too small to extract a large foreign body, without fragmentation. In such cases, our strategy was to extract the foreign body along with the endotracheal tube during planned extubation.

Data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2019 (version 2109, build 14430.20306). Thereafter, the data were analysed using MedCalc® Statistical Software version 22.016 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org, 2023). We used univariate analysis (mean, median) with calculation of confidence interval (CI). Analysis of patient age cumulative frequency distribution was used. Then, we analysed the odds ratio (OR) and relative risk to find the strength of the association between different age groups.

Patient ages varied from 9 months to 11 years. The mean age was 46.7 months (95%CI: 27.91-65.5). The median age was 23.5 months (95%CI: 19.49-44.77).

We observed age clustering in children with foreign body aspiration who underwent endoscopic intervention at our institution. There were three age subgroups: (1) 0-25 months; (2) 40-60 months; and (3) 120-140 months (Figure 1). Fourteen of the 24 patients (58.3%) were aged < 25 months.

Fifty percent of tracheobronchial foreign bodies (12 out of 24) were of inorganic origin, most often plastic toy products or parts thereof. In several cases, a screw, a dental pulp extractor, and a light-emitting diode were found. The remaining 50% of cases were of organic origin (nuts, sunflower seeds, and orange peels). Only four of the 24 foreign bodies were radiopaque and could be seen on radiography.

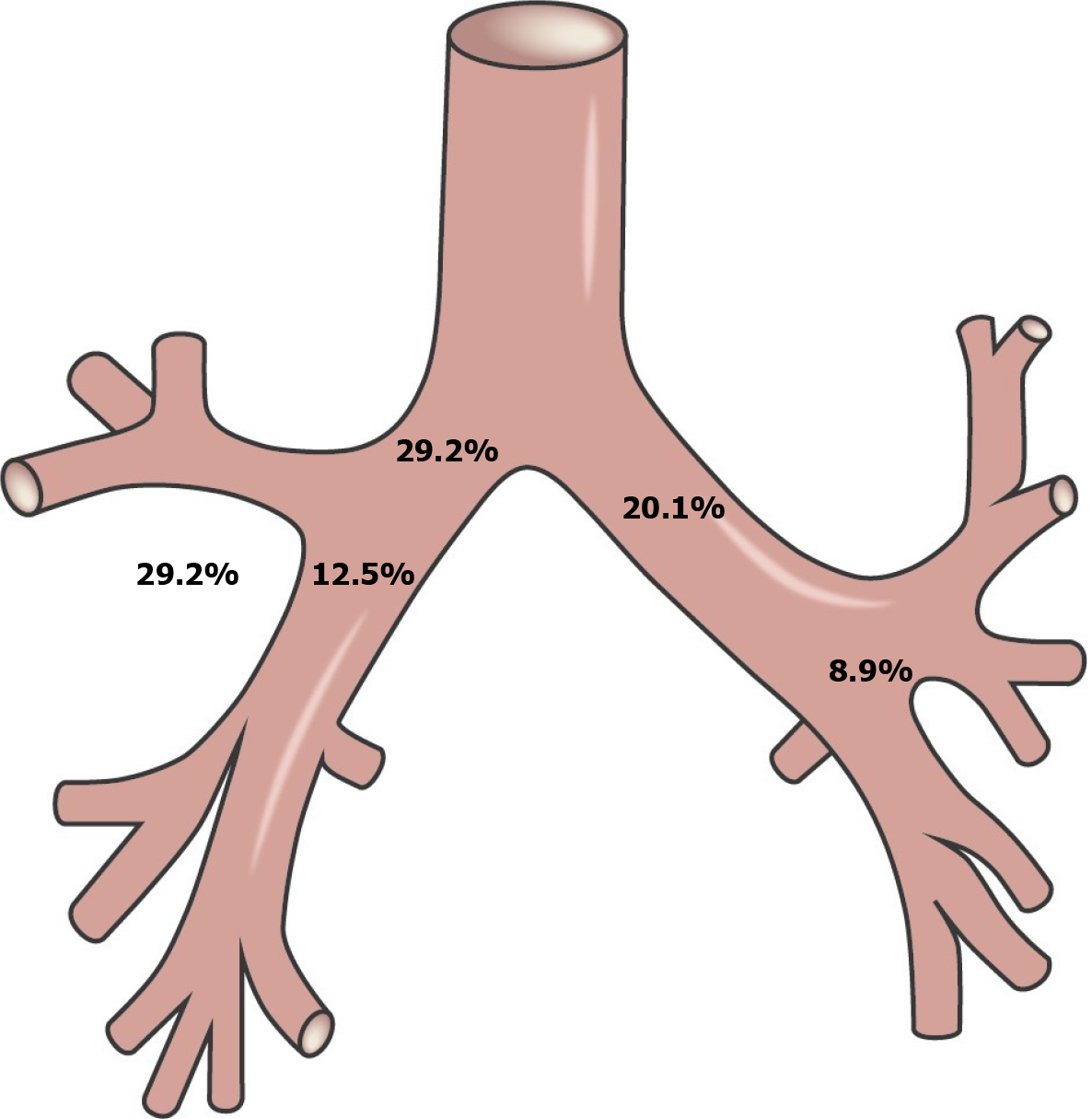

Most often, 17 of 24 (71%) foreign bodies were localised in the right parts of the tracheobronchial tree, whereas only 7 of 24 (29%) foreign bodies were found in the left parts (Figure 2 and Table 2). In addition, we analysed the origin of the foreign body and its topography after aspiration according to the age subgroup (Table 3).

| Tracheobronchial tree localization | Number of cases | % |

| Right main bronchus | 7 | 29.2 |

| Left main bronchus | 5 | 20.1 |

| Intermediate bronchus | 3 | 12.5 |

| Right lobar bronchi | 7 | 29.2 |

| Left lobar bronchi | 2 | 8.9 |

| Age (month) | Topography | Origin of foreign body | ||

| Large bronchi | Lobar and segmental bronchi | Organic (%) | Non-organic (%) | |

| 0-25 | 9 | 5 | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) |

| 40-60 | 3 | 2 | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

| 120-140 | 3 | 2 | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

Analysis of the OR and relative risk of finding topographic differences in foreign body localisation after aspiration between the age subgroups was not statistically significant. However, we found that expectancy of an organic tracheobronchial foreign body was significantly higher in 0-25 months subgroup than that in older ones when subgroups 40-60 and 120-140 months were combined together (OR = 10.0, 95%CI: 1.44-29.26, P = 0.0197).

Successful foreign body extraction was performed in all cases (Table 1). Conversion to a rigid bronchoscope was not required in any of the cases. In 11 of the 24 cases, foreign body extraction was performed using endotracheal tubes of various diameters. No major complications (massive bleeding, perforation of the tracheobronchial tree, or asphyxia) were noted, and no minor complications (transient hypoxia and laryngeal oedema) were recorded.

Foreign body aspiration represents one of the very frequent accidents in children. Young children tend to put small objects into the mouth, they also often eat during activity and move around with food in the mouth. Quite often older siblings or even parents represent a risk as they may give the young child food inappropriate for age, such as nuts, peanuts, seeds[15].

That might be one of the reasons why airway foreign bodies are mostly organic in nature (64%-93%)[10,16,17]. In

The recommendations of the currently existing guidelines favour rigid bronchoscopy as the method of choice for tracheobronchial foreign body extraction[13,14,19]. Some authorities state that flexible bronchoscopy can be used for foreign body extraction but only if the operator has the ability to quickly switch to a rigid bronchoscope[12,13]. Based on a survey of German specialists in paediatric pulmonology in 2017, it was reported that only 20% of medical centres in Germany prefer to use flexible bronchoscopy for foreign body removal[12]. Authors of this survey state that this approach is more common in centres with a relatively small number of manipulations and explained this percentage by the lack of equipment and sufficient expertise and skills in performing rigid bronchoscopy.

Schramm et al[12] concluded that rigid bronchoscopy is a more effective and safer method (the success rate of the "primary flexible method" is 73.9%, while the success rate of the "primary rigid method" is 99.4%), which, however, is not consistent with data found in literature (Table 4).

| Ref. | Number of patients | Efficacy of flexible bronchoscopy alone (%) | Complications (%) |

| Ding et al[10] | 165 | 97.6 (161/165) | Transient hypoxia and tachypnoea; one severe complication (no specified) |

| Tenenbaum et al[11] | 28 | 100 (28/28) | No/no specified |

| Kim et al[16] | 20 | 90 (18/20) | 10 (n = 2), mild laryngeal oedema |

| Yüksel et al[17] | 31 | 93.5 (29/31) | 0 |

| Tang et al[22] | 1027 | 91.7 (938/1027) | 12.9 (transient hypoxia); 2.3 (bleeding, laryngeal oedema, bradycardia, airway leak) |

| Golan-Tripto et al[23] | 40 | 95 (38/40) | 0 |

| Suzen et al[24] | 24 | 100 (24/24) | 8.4 laryngeal oedema |

| Ciftci et al[25] | 283 | 92 (260/283) | 3.5 (transient hypoxia and bradycardia); 3.9 (minor bleeding); 3.9 (minor nosebleed); 2.8 (laryngeal oedema) |

A number of studies have confirmed the safety and effectiveness of flexible bronchoscopy as a therapeutic procedure for foreign body aspiration[10,11,16,20,21], suggesting that it can be a first-line therapy for the extraction of foreign bodies[17,20-23], with up to 100% efficiency in experienced hands[11,24]. Fewer complications were noted in comparison to rigid bronchoscopy, as well as a shorter duration (42 min vs 58 min[20] and 36 min vs 53 min)[23]. For example, Tang et al[22] reported a 91.3% success rate for foreign body removal with a flexible endoscope in a retrospective evaluation of 1027 children. Notably, all the above studies emphasised the importance of suitable equipment and endoscopic tools, as well as sufficient experience and skills of the personnel performing the extraction.

Despite the high success rates for flexible bronchoscopy, it should be recognised that the rigid technique has a high efficiency (97%-99.7%), which has been repeatedly demonstrated in a large number of children[25-27]. Simultaneously, less invasiveness and a shorter duration of manipulation are expected advantages of the flexible technique, which should be reflected in fewer complications. We also actively used rigid bronchoscopy for foreign body aspiration at our centre until 2014; however, the appearance of flexible bronchoscopes of various diameters and appropriate endoscopic tools displaced this method.

A large study published in 2017 involving 197 European centres performing paediatric bronchoscopy provided two interesting facts: (1) 65 of 197 centres had only flexible bronchoscopes and no rigid bronchoscopes at all; and (2) 38 of 148 centres providing 24/7 care for patients with suspected tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration did not have rigid bronchoscopes[28].

Our experience indicates that flexible bronchoscopy is a competitive alternative to rigid techniques, particularly in relation to the distal tracheobronchial tree in young children. Despite having a rigid bronchoscope set and the skills to perform this manipulation, we have not used rigid bronchoscopy for the aspiration of foreign bodies since 2017. Furthermore, our commitment to flexible bronchoscopy can be explained by the availability of several appropriate endoscopic instruments for a 1.2-mm working channel.

The main limitation of this study is that the majority of available studies, including this article, were retrospective analyses with a low level of evidence. This information can be manipulated depending on the personal preferences of the expert.

Successful bronchoscopy intervention is the result of multidisciplinary teamwork (anaesthesiologists and endoscopy experts). We believe that at least one multicentre randomised controlled trial with the following points should be performed: (1) A large number of patients should be included; (2) all complications (minor and major) with pre-agreed unified criteria should be noted; (3) a comparison of the procedure duration should be included; and (4) operator experience should be considered. We report that flexible bronchoscopy is an effective and safe method for tracheobronchial foreign body extraction in children.

| 1. | Panchabhai TS, Mehta AC. Historical perspectives of bronchoscopy. Connecting the dots. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:631-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hill W. Foreign Bodies removed with the aid of Upper Bronchoscopy in an Infant 13 months old. Proc R Soc Med. 1912;5:37-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Burrington JD, Cotton EK. Removal of foreign bodies from the tracheobronchial tree. J Pediatr Surg. 1972;7:119-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hiller C, Lerner S, Varnum R, Bone R, Pingelton W, Kerby G, Ruth W. Foreign body removal with the flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope. Endoscopy. 1977;9:216-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cunanan OS. The flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope in foreign body removal. Experience in 300 cases. Chest. 1978;73:725-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wood RE, Sherman JM. Pediatric flexible bronchoscopy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980;89:414-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Diez-Ferrer M, Gratacos AR. Ultrathin Bronchoscopy: Indications and Technique. In: Díaz-Jimenez J, Rodriguez A. (eds) Interventions in Pulmonary Medicine. Springer, Cham. 2018;35-45. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Chang DT, Abdo K, Bhatt JM, Huoh KC, Pham NS, Ahuja GS. Persistence of choking injuries in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;144:110685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dongol K, Neupane Y, Das Dutta H, Raj Gyawali B, Kharel B. Prevalence of Foreign Body Aspiration in Children in a Tertiary Care Hospital. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021;59:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ding G, Wu B, Vinturache A, Cai C, Lu M, Gu H. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration in children: A retrospective single-center cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tenenbaum T, Kähler G, Janke C, Schroten H, Demirakca S. Management of Foreign Body Removal in Children by Flexible Bronchoscopy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2017;24:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schramm D, Ling K, Schuster A, Nicolai T. Foreign body removal in children: Recommendations versus real life-A survey of current clinical management in Germany. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:656-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schramm D, Freitag N, Nicolai T, Wiemers A, Hinrichs B, Amrhein P, DiDio D, Eich C, Landsleitner B, Eber E, Hammer J; Special Interest Group on Pediatric Bronchoscopy of the Society for Pediatric Pneumology (GPP) and invited Societies involved in pediatric airway endoscopy. Pediatric Airway Endoscopy: Recommendations of the Society for Pediatric Pneumology. Respiration. 2021;100:1128-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pérez-Frías J, Moreno Galdó A, Pérez Ruiz E, Barrio Gómez De Agüero MI, Escribano Montaner A, Caro Aguilera P; Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica. [Pediatric bronchoscopy guidelines]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:350-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Goussard P, Pohunek P, Eber E, Midulla F, Di Mattia G, Merven M, Janson JT. Pediatric bronchoscopy: recent advances and clinical challenges. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2021;15:453-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim K, Lee HJ, Yang EA, Kim HS, Chun YH, Yoon JS, Kim HH, Kim JT. Foreign body removal by flexible bronchoscopy using retrieval basket in children. Ann Thorac Med. 2018;13:82-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yüksel H, Yaşar A, Açıkel A, Topçu İ, Yılmaz Ö. May the first-line treatment for foreign body aspiration in childhood be flexible bronchoscopy? Turk J Emerg Med. 2021;21:184-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Antón-Pacheco JL, Martín-Alelú R, López M, Morante R, Merino-Mateo L, Barrero S, Castilla R, Cano I, García A, Gómez A, Luna-Paredes MC. Foreign body aspiration in children: Treatment timing and related complications. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;144:110690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, Brown KK, Costabel U, du Bois RM, Drent M, Haslam PL, Kim DS, Nagai S, Rottoli P, Saltini C, Selman M, Strange C, Wood B; American Thoracic Society Committee on BAL in Interstitial Lung Disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1004-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 773] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | De Palma A, Brascia D, Fiorella A, Quercia R, Garofalo G, Genualdo M, Pizzuto O, Costantino M, Simone V, De Iaco G, Nex G, Maiolino E, Schiavone M, Signore F, Panza T, Cardinale F, Marulli G. Endoscopic removal of tracheobronchial foreign bodies: results on a series of 51 pediatric patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36:941-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kapoor R, Chandra T, Mendpara H, Gupta R, Garg S. Flexible Bronchoscopic Removal of Foreign Bodies from Airway of Children: Single Center Experience Over 12 Years. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56:560-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tang LF, Xu YC, Wang YS, Wang CF, Zhu GH, Bao XE, Lu MP, Chen LX, Chen ZM. Airway foreign body removal by flexible bronchoscopy: experience with 1027 children during 2000-2008. World J Pediatr. 2009;5:191-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Golan-Tripto I, Mezan DW, Tsaregorodtsev S, Stiler-Timor L, Dizitzer Y, Goldbart A, Aviram M. From rigid to flexible bronchoscopy: a tertiary center experience in removal of inhaled foreign bodies in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1443-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Suzen A, Karakus SC, Erturk N. The role of flexible bronchoscopy accomplished through a laryngeal mask airway in the treatment of tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;117:194-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ciftci AO, Bingöl-Koloğlu M, Senocak ME, Tanyel FC, Büyükpamukçu N. Bronchoscopy for evaluation of foreign body aspiration in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1170-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gang W, Zhengxia P, Hongbo L, Yonggang L, Jiangtao D, Shengde W, Chun W. Diagnosis and treatment of tracheobronchial foreign bodies in 1024 children. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:2004-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Boufersaoui A, Smati L, Benhalla KN, Boukari R, Smail S, Anik K, Aouameur R, Chaouche H, Baghriche M. Foreign body aspiration in children: experience from 2624 patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:1683-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Schramm D, Yu Y, Wiemers A, Vossen C, Snijders D, Krivec U, Priftis K, Eber E, Pohunek P. Pediatric flexible and rigid bronchoscopy in European centers-Availability and current practice. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:1502-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/