Published online Jun 9, 2024. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v13.i2.91268

Revised: April 13, 2024

Accepted: April 18, 2024

Published online: June 9, 2024

Processing time: 164 Days and 10.1 Hours

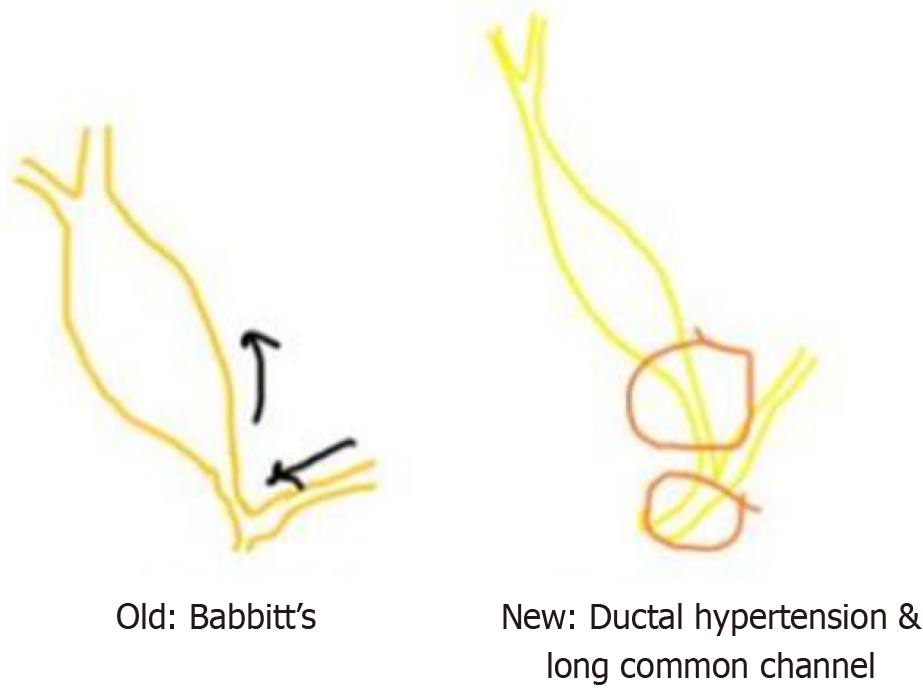

The choledochal cyst (CC) can be better termed as biliary tract malformation because of the close association of embryology and etiology in the causation of CC. Contrary to Babbitt's postulation of reflux, damage and dilatation, reflux was not demonstrable as the causative factor in all varieties of CC. High pressure in the biliary system, otherwise termed ductal hypertension, is put forth as an alternative to explain the evolution of CC. The forme fruste type, which does not find a place in the standard classification, typifies the ductal hypertension hypothesis. Hence a closer, in-depth review would be able to highlight this apt terminology of biliary tract malformation.

Core Tip: The biliary tract malformation has undergone a metamorphosis from its previous nomenclature of choledochal cyst owing to a variety of reasons. The etiology, embryopathology and the current classification require revisiting due to the same. The review looks at the same in detail.

- Citation: Govindarajan KK. Current status of the biliary tract malformation. World J Clin Pediatr 2024; 13(2): 91268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v13/i2/91268.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v13.i2.91268

Choledochal cyst (CC) accounts for 1/1000 to 1/150000 live births, with high incidence in Asia, especially Japan. The majority (80%) would present by ten years of age. Less than 1% of the benign biliary tract disorders are due to CC, accounting for the relative rarity in adults. Being a disease of children, CC shares a closer link with embryo pathogenesis[1,2].

The classification of CC into various types considers the dilatation/segment of the biliary tract involved. This may have an etio-pathological association. The old school of thought (Babbitt) is subject to debate as the postulation does not satisfactorily explain the different types of CC. Hence a review of embryology is in order to understand the drift to the current thinking[1,2].

The traditional concept referred to inflammation as the initiating factor, leading to damage and dilatation. Based on contrast reflux into the pancreatic duct during intraoperative cholangiography, Babbitt suggested that pancreatic enzyme backflow into the bile duct initiates inflammatory damage to the bile duct resulting in progressive dilatation with CC formation. According to this pancreatic reflux-induced etiology, Amylase levels may need to be elevated to justify the presence of reflux[3]. But the cyst Amylase level measurements do not universally show an increase. Rather, what is known, is an inverse co-relation of the CC size with the cyst pressure[4]. Hence, an increase in the intraluminal pressure arising from distal bile duct obstruction was shown as the offending factor in the causation of CC. Relative stenosis of the distal bile duct could be the primary factor which can cause elevation of pressure with resultant intraductal hypertension[5]. Not only does this go against traditional thinking but it also sets up the stage for reconsideration of etiology (Figure 1).

The ductal plate malformation is the embryological basis of Caroli’s disease. At the time of bile duct formation, initial thin plates (single layer) of bile duct around the portal vein get reinforced (double layer), resulting in robust bile ductules after extensive resorption. In case of failure to complete resorption with partial/incomplete retention of the primitive ductal plate can lead to large dilated segments. When this occurs at the level of the segmental ducts or intermediate-size ducts, the resultant insult can be either Caroli’s disease or Caroli’s syndrome, respectively[6].

A different mechanism must be highlighted at this juncture for the evolution of the CC types I/II/IV. The pancreatic duct and common bile duct join together to form a common channel, which is sandwiched between the sphincter of Oddi (entry into D2) and the sphincters of choledochus and pancreaticus. Thus the common channel is usually a short length of ‘uneventful’ passage. Trouble brews when the common channel lengthens for various embryological factors, as the anomalous junction of the biliary and pancreatic with abnormal sphincters lets loose the tight compartmentalization of fluid travel, resulting in reflux of pancreatic contents across into the bile duct. The stage is now set for reflux, inflammation and damage. Thus the presence of a long common channel would lead to a vicious cycle of stasis and dilatation, ultimately evolving into a CC. Should an anomalous proliferation of the biliary epithelium occur during fetal life, this common channel will become longer than the length of the sphincter (which remains constant) with the accompaniment of reflux[7].

Choledochocele or Type III CC stands apart from the other counterparts due to a different mechanism of patho

In addition, Caroli’s disease, in view of its familial association and link to hepatic fibrosis, is possibly a separate and different type from the rest of the biliary tract malformation and it may have to stand out as a different entity. Of note embryologically is its relation to ductal plate malformation which pursues another recognizably different pathway[10].

The hallmark of CC, namely gross biliary ductal dilatation, can sometimes not be present but may have clinically significant pain abdomen, as identified in a unique subtype of CC, namely the ‘forme fruste’ type of CC. The presence of marginal dilatation or absent dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct with malunion of the pancreato-biliary junction is referred to as the ‘forme fruste’ type of CC. The striking relief of symptoms (pain abdomen) post -operatively, after the bile duct is separated from the pancreatic duct during surgical reconstruction (excision of bile duct and roux en y hepatico-jejunostomy) has firmly established the association of ductal hypertension in this subtype[11]. A combination of long common channel with a minimal dilated common bile duct (< 10 mm) noted on an intra-op cholangiogram or Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio Pancreatography helps in the identification of this condition[12].

Hamada et al[13] considered the dilatation of bile duct by grouping them into two categories, one with biliary dilatation in combination with abnormal pancreato-biliary junction (congenital biliary dilatation or CC) and the other with only abnormal pancreato-biliary junction.

The elaboration of abnormal pancreato-biliary junction or pancreato-biliary malunion is out of scope as it deserves an in-depth and focussed review.

Todani’s classification of CC dates back to 1977, which attempts to put together the various types as per the understanding of the causation of CC relevant at that point in time. Over a period of time, newer studies have changed the understanding of the etiology of CC, prompting a relook into the traditional classification. Not only the surgical treatment but also the malignancy risk is different among the CC types suggesting a newer regrouping logically agreeable to the etiology as well[14]. A simpler Kings’ college classification which is a management-based classification has been proposed as an alternative[15,16]. But none are widely adopted in current clinical practice.

Varied etiology owing to molecular mechanisms has been put forth recently. Analysis of the molecular characteristics has shown that the cystic and fusiform types of CC have different molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis[17]. A higher rate of harmful alleles in genes involved in soft tissue disorders and conditions related to tissue overgrowth may be linked to the formation of the stenotic distal bile duct, ultimately resulting in proximal dilatation and CC[18]. Further studies are required to characterise in detail the genetic polymorphisms involved in the pathogenesis of CC.

CC appears to be a misnomer and biliary tract malformation, the current terminology is apt and justifiably in line with the evolving etiopathology. In continuum, the same logic is applicable to the Alonso Lej classification of CC as well, which needs to give way to a system of modified sorting of the various types of Biliary Tract malformation.

| 1. | Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts: part 1 of 3: classification and pathogenesis. Can J Surg. 2009;52:434-440. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Singham J, Yoshida EM, Scudamore CH. Choledochal cysts: part 2 of 3: Diagnosis. Can J Surg. 2009;52:506-511. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Babbitt DP, Starshak RJ, Clemett AR. Choledochal cyst: a concept of etiology. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Turowski C, Knisely AS, Davenport M. Role of pressure and pancreatic reflux in the aetiology of choledochal malformation. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1319-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Davenport M, Basu R. Under pressure: choledochal malformation manometry. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:331-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vijayan V, Tan CE. Development of the human intrahepatic biliary system. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1999;28:105-108. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Pancreatic juice can reflux into the bile duct in patients without anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1021-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wheeler WIC. An unusual case of obstruction to the common bileduct (choledochocele?). Br J Surg. 1940;27:446-448. |

| 9. | Alonso-Lej F, Rever Wb Jr, Pessagno DJ. Congenital choledochal cyst, with a report of 2, and an analysis of 94, cases. Int Abstr Surg. 1959;108:1-30. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Desmet VJ. Congenital diseases of intrahepatic bile ducts: variations on the theme "ductal plate malformation". Hepatology. 1992;16:1069-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thomas S, Sen S, Zachariah N, Chacko J, Thomas G. Choledochal cyst sans cyst--experience with six "forme fruste" cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shimotakahara A, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, Okada Y, Yanai T, Lane GJ, Miyano T. Forme fruste choledochal cyst: long-term follow-up with special reference to surgical technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1833-1836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hamada Y, Ando H, Kamisawa T, Itoi T, Urushihara N, Koshinaga T, Saito T, Fujii H, Morotomi Y. Diagnostic criteria for congenital biliary dilatation 2015. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:342-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mathur P, Gupta PK, Udawat P, Mittal P, Nunia V. Hepatobiliary malformations: proposed updation of classification system, clinicopathological profile and a report of largest pediatric giant choledochal cyst. HPB (Oxford). 2022;24:422-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dabbas N, Davenport M. Congenital choledochal malformation: not just a problem for children. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mishra PK, Ramaswamy D, Saluja SS, Patil N, Chandrashekhar S. Unusual variants of choledochal cyst: how to classify. Am Surg. 2013;79:E162-E164. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lv Y, Xie X, Pu L, Wang Q, Wang J, Pu S, Ai C, Liu Y, Chen J, Xiang B. Molecular Characteristics of Choledochal Cysts in Children: Transcriptome Sequencing. Front Genet. 2021;12:709340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wong JK, Campbell D, Ngo ND, Yeung F, Cheng G, Tang CS, Chung PH, Tran NS, So MT, Cherny SS, Sham PC, Tam PK, Garcia-Barcelo MM. Genetic study of congenital bile-duct dilatation identifies de novo and inherited variants in functionally related genes. BMC Med Genomics. 2016;9:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/