Published online Nov 9, 2021. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v10.i6.151

Peer-review started: January 7, 2021

First decision: May 6, 2021

Revised: June 7, 2021

Accepted: September 22, 2021

Article in press: September 22, 2021

Published online: November 9, 2021

Processing time: 305 Days and 14.4 Hours

Firearm-associated injuries (FAIs) are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in children living in the United States. Most victims of such injuries survive, but may experience compromised function related to musculoskeletal injuries. Although complex firearm-associated fractures (FAFs) often require specialized orthopaedic, vascular, and plastic surgical intervention, there is minimal research describing their management and outcomes. The purpose of this study is to describe the epidemiology and presentation of pediatric FAFs, as well as evaluate the management and outcomes of these injuries.

To describe the epidemiology and presentation of pediatric FAFs, as well as evaluate the management and outcomes of these injuries.

A retrospective chart review was performed at a major, pediatric level 1 trauma center. The study included patients aged 18 or younger who presented with FAIs between 2008-2018. Additional data was collected on patients with FAFs inclu

Between 2008 and 2018, there were a total of 61 patients who presented with FAIs. In this cohort, 21 patients (34%) sustained FAFs (25 fractures) with a mean age of 11 (Range: 10 mo to 18 years old) at the time of presentation. Approximately 52% (n = 11) of patients with FAFs were male, 76% (n = 8 and n = 8, respectively) identified as black or other, and 71% (n = 15) had government insurance. FAFs were most commonly noted in the upper extremity (n = 7) and lower extremity (n = 6). In patients with FAFs, the mean ISS at presentation was 11.38 (Range: 2-38), and 24% of patients (n = 5) were classified as having a major trauma. There were no significant differences in age, sex, race, and payor type in FAF patients that presented with and without major trauma (P > 0.05). When comparing FAF and non-FAF patients, there was a statistically significant difference in ISS (11.38 vs 14.45, P = 0.02). In total, 33% (n = 7) of patients with FAFs required orthopaedic surgical management, which was most commonly comprised of debridement (n = 6/7, 86%), and 14% (n = 1/7) of these patients required coordinated care with plastic and/or vascular surgery. There were no significant differences in age and payor type in patients with FAFs treated with and without orthopaedic surgery. Of the patients with FAFs, 52% (n = 11) had a minimum 90-d follow-up, and 48% (n = 10) had a minimum 2-year follow-up. Two patients were readmitted within 90-d, while one patient required a reoperation within 2-years.

Over 25% of FAIs in pediatric patients result in FAFs. FAFs often present to pediatric trauma centers and the majority of these injuries occur in non-Caucasian males with government insurance. Most FAFs do not need orthopaedic surgical management; 14% of these injuries require subspecialty care by orthopaedic surgery, vascular surgery, or plastic surgery. Patients with FAFs also have lower ISS compared to patients who sustained FAIs without fracture. Thus, these patients should be treated at pediatric trauma centers with specialty care and additional research is needed to focus prevention efforts, understand reasons for poor follow-up, and evaluate outcomes after injury.

Core Tip: Over 25% of firearm-associated injuries (FAIs) in pediatric patients result in firearm-associated fractures (FAFs). FAFs often present to pediatric trauma centers and the majority of these injuries occur in non-Caucasian males with government insuran

- Citation: Lieu V, Carrillo LA, Pandya NK, Swarup I. Pediatric firearm-associated fractures: Analysis of management and outcomes. World J Clin Pediatr 2021; 10(6): 151-158

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v10/i6/151.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v10.i6.151

Firearm-associated injuries (FAIs) are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in children living in the United States. Recently, the injuries and fatalities associated with firearms have come to the forefront of public discourse in the United States. These injuries account for almost twenty pediatric hospitalizations per day across the country[1], and represent the cause of death for a quarter of adolescents 15-19 years old[2].

Despite the large number of children affected by firearm-related violence, there is a paucity of literature focusing on the rates of firearm associated fractures (FAFs) as well as the orthopaedic management of these injuries. Additionally, there are few studies focusing on concomitant injuries that occur with FAFs, such as vascular and soft tissue injuries. In a study by Blumberg et al[3], the incidence of FAFs in patients < 20 years of age between 2003 to 2012 was 90.7 per 100000 admissions. These patients were more likely to be male, African American, and older in age. The authors also noted an increase in overall incidence of FAFs during the study period, with the largest increase in children ages 0-4. These findings underscore the need for additional research focusing on the epidemiology, management, and outcomes of FAFs so that health care professionals are better able to counsel and manage patients, as well as inform policy makers to allocate resources and focus on prevention programs.

The aim of this study was to describe the epidemiology and presentation of fractures secondary to firearm injuries among children and adolescents at a major metropolitan trauma center over a ten-year period. In addition, we aimed to assess the management and outcomes of these complex musculoskeletal injuries. We hypothe

A retrospective chart review was performed at a major pediatric level 1 trauma center. This study included patients aged 18 or younger that presented with a FAI between 2008 and 2018. Additional data was collected on patients specifically presenting with a FAF. Patients with isolated fractures of the hand, spine, skull, face, or ribs were excluded. This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Patients were identified from an institutional trauma database, which provided initial demographic and clinical data. This database captures all patients with FAIs seen in the emergency room. Charts for patients with FAFs were reviewed to collect additional clinical and radiographic data. Demographic data included patient age, sex, race, and payor status. Clinical data included year of presentation, fracture location, injury severity score (ISS), surgical management, need for other surgical services, rates of 90-d and 2-year follow-up, as well as 90-d and 2-year radiographic and clinical outcomes. The data were summarized using counts, percentages, ranges, and means. Univariate analyses comprised of student’s t-test and chi-square analysis were performed to compare differences in patients with and without FAFs, with and without other major trauma, and patients that were or were not treated with ortho

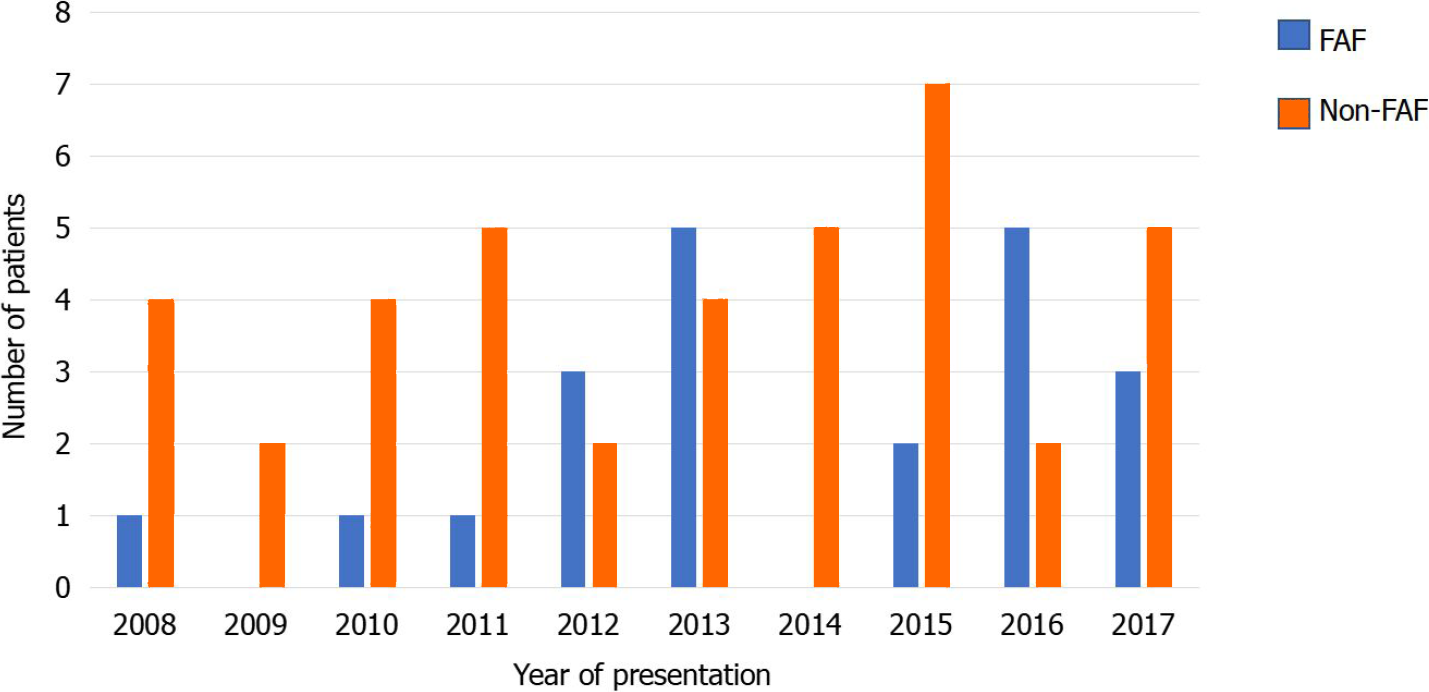

During the ten-year study period, we identified a total of 61 patients who sustained FAIs (Figure 1). Of these, 21 patients (34%) suffered FAFs and presented for care at our institution. The average age at time of presentation for all FAIs was 11 years, and approximately 70% of patients (n = 43) were male. Approximately 80% of patients identified as black or other (n = 25 and n = 24, respectively), and 59% (n = 36) had government insurance (Table 1). The mean ISS for all FAIs was 14.48 (Range: 4 to 50).

| Number | |

| Age at injury | |

| 0–12 years old | 9 (43%) |

| 13–18 years old | 12 (57%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 11 (52%) |

| Female | 10 (48%) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 2 (10%) |

| Black | 8 (38%) |

| White | 2 (10%) |

| Other | 8 (38%) |

| Unknown | 1 (5%) |

| Insurance payor | |

| Government | 15 (71%) |

| Non-government | 6 (29%) |

| Location of fracture | |

| Upper extremity | 7 (28%) |

| Lower extremity | 6 (24%) |

| Foot | 5 (20%) |

| Pelvis | 5 (20%) |

| Unknown | 2 (8%) |

| AO fracture classification | |

| 14.A1 | 61A1.3 |

| 14A3 | 61A2.2 |

| 14B1 | 61A2.3 |

| 14B2 | 62A2.1 |

| 21.B1 | 81.1.C3 |

| 2R2C3 | 82.C3 |

| 31.3A3 | 82C1 |

| 32.C3 | 84B |

| 33A3.2 | 87.C3 |

| 34B1.2 | |

| 42.A2 | |

| Injury severity score | |

| ≤ 15 | 16 (76%) |

| > 15 | 5 (24%) |

| Treatment | |

| Orthopaedic surgical management | 7 (33%) |

| Debridement1 | 6 (86%) |

| Internal fixation1 | 5 (71%) |

| Both1 | 4 (57%) |

| No orthopaedic surgical management | 10 (48%) |

| Unknown | 4 (19%) |

There were 25 FAFs in 21 patients over the study period. Of the patients who sustained FAFs, the average age at time of presentation was 11 years, and 52% were male (n = 11). Approximately 76% identified as black or other (n = 7 and n = 9, respectively), and 67% (n = 14) had government insurance. The most common fracture locations included the upper extremity (n = 7) and lower extremity (n = 6), specifically in the scapula and femur (n = 3 and n = 3, respectively). Four patients had multiple fractures, of which two patients had both FAFs in the foot; one patient had both FAFs in the pelvis; and one patient had FAFs in the pelvis and lower extremity. The mean ISS at presentation was 11.38 (Range: 2 to 38), and 24% of patients (n = 5) were classified as having a major trauma, defined as an ISS greater than 15. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, race, and payor between patients with and without major trauma (P > 0.05).

In total, 33% of patients (n = 7) required orthopaedic surgical management, which was most commonly comprised of debridement (n = 6, 86%) and internal fixation (n = 5, 71%). Internal fixation consisted of a variety of methods, including Kirschner wires, intramedullary devices, and plating (Table 1). Intramedullary devices were commonly used for lower extremity FAFs and k-wires or plate fixation was commonly used for upper extremity FAFs. There were no significant differences in sex and payor between patients treated with and without orthopaedic surgery.

In this cohort, approximately 14% of patients (n = 3/21) needed coordinated care with plastic and/or vascular surgery. Of the remaining patients, 48% of patients (n = 10) were treated non-operatively with modified weight-bearing, bracing, or splinting.

Among all FAF patients, 52% (n = 11) had a minimum 90-d follow-up and 48% (n = 10) had a minimum 2-year follow-up. Of the 7 patients treated with orthopaedic surgery, 5 patients (71%) had 90-d follow-up, and 5 patients (71%) had two–year follow-up. All patients with radiographs at two-years had evidence of radiographic healing. In this cohort, 1 patient (14%) was readmitted within 90-d for ulnar nerve reconstruction, and 1 patient (14%) required a reoperation within 2-years for a hardware removal and a subsequent reoperation for revision fixation for malunion.

In our study, 66% patients (n = 40) had a FAI without an associated fracture. In this group, the average age at time of presentation was 11 years. Eighty percent (n = 32) of these patients were male, and 85% identified as black or other (n = 18 and n = 16, respectively). 50% of these patients had government insurance. There was no statistically significant difference in age, sex, race, and payor between our FAF and non-FAF group (P > 0.05). However, there was a statistically significant difference in average ISS between FAF and non-FAF patients (P = 0.02) with average scores of 9.5 for FAF patients and 14.5 for non-FAF patients.

The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 3443 fatalities and 18227 nonfatal FAIs occurred in patients below 19 years old in 2017 alone[4]. In a retrospective analysis of emergency department and ambulatory visits from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, Srinivasan et al[5] calculated an annual rate of FAIs of 23.9 per 100000 children between 2001 and 2010. A similar trend was noted for FAFs by Blumberg et al[3] with a recent increase in the number of such fractures.

Our study identified a total of 61 patients affected by FAIs over the last 10 years. Of this group, 21 patients experienced a total of 25 fractures. The majority of FAFs occurred within the last 5 years of the study period. The increasing incidence of FAFs in the last 5 years as well as the affected patient population is consistent with previous studies[3,5-10]. A previous study noted an increase in nonfatal FAFs over a 10-year period, and another study noted an overall increase in FAFs over time[3,5]. Ad

The majority of FAIs in this study were noted to occur in non-Caucasian males and patients with government insurance. This trend was also found in our FAF patients and is representative of our patient population. These findings are consistent with findings from a large database study, which noted FAFs were more commonly found in patients who were male, black, and uninsured in comparison to children who were being evaluated for non-firearm related complaints[5]. This pervasive trend under

In general, many patients with FAFs do not need orthopaedic surgical management, but orthopaedic, vascular, or plastic surgical care may be required in up to half of all patients with FAFs. This is consistent with our hypothesis and the current literature, which supports the use of local wound care and antibiotics among low-velocity gunshot wounds with stable fracture patterns[11]. However, injuries caused by high-energy weapons or those with an unstable fracture pattern, vascular injury, or significant soft tissue defects may require formal surgical irrigation and debridement, fixation, vascular repair, or grafting, with intravenous antibiotics. In addition, a recent study by Berg et al[9] noted that FAFs were 1.9 times more likely to be associated with vascular and nerve injury, which may require care coordination across specialties.

In our study, approximately a third of our patients required orthopaedic surgical management, and approximately 14% of these patients needed coordinated care with plastic and/or vascular surgery. There were no significant differences in sex and payor between patients treated with and without orthopaedic surgery. Despite the lower rates of operative intervention, this finding highlights the importance of multispecialty care and a practice of having these patients managed at major trauma centers. This finding may be critical for those patients requiring orthopaedic surgical management.

This study has several limitations. This is a single center study and our sample size is small, which may affect the generalizability of our findings as well as our ability to perform analyses that are adequately powered. However, our institution serves a racially and socioeconomically diverse population, and it is the only level 1 pediatric trauma center in this geographic region. Additionally, this study only has short and long-term follow-up for approximately half of the cohort, and it has limited clinical and functional data for evaluation. This limitation may be due to the high rate of referrals to our institution, but it could also reflect the need for continued emphasis on follow-up for this patient population. Although we have a low rate of patient follow-up, readmission and reoperation were noted to occur. Thus, this finding emphasizes the need for closer follow-up to monitor for complications such as infection, malunion, and nonunion, which have been well-documented in the literature[11-13]. Lastly, we do not have any patient-reported outcome measures, which limits our ability to compare outcomes to other patients or populations.

In conclusion, FAFs are noted in approximately a third of all FAIs. FAFs have become increasingly more common at our institution, and there is a high rate of FAFs among certain demographic and socioeconomic groups. While these injuries can cause lasting effects on these patients, they may not be associated with major trauma. These findings are consistent with previous studies and should serve as a call to providers, administrators, and policy makers to investigate and propose ways to address this issue. The findings from this study also underscore the need for multidisciplinary care and close follow-up to minimize the risk of readmission, reoperation, and poor outcomes. Patients with FAFs often have complex needs and should be treated at pediatric institutions with specialty care. Additional effort is needed to maintain follow-up and decrease the risk for readmission after this injury. The identification of factors, which may prevent follow-up in this population, could provide areas to target future interventions to ensure adequate care and optimize outcomes in these patients.

Firearm-associated injuries (FAIs) are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in children living in the United States. Recently, the injuries and fatalities associated with firearms have come to the forefront of public discourse in the United States.

Most victims of such injuries survive, but may experience compromised function related to musculoskeletal injuries. Although complex firearm-associated fractures (FAFs) often require specialized orthopaedic, vascular, and plastic surgical inter

The purpose of this study is to describe the epidemiology and presentation of pediatric FAFs, as well as evaluate the management and outcomes of these injuries.

A retrospective chart review was performed at a major, pediatric level 1 trauma center. The study included patients aged 18 or younger who presented with FAIs between 2008-2018. Additional data was collected on patients with FAFs including demo

Between 2008 to 2018, there were a total of 61 patients who presented with FAIs. In this cohort, 21 patients (34%) sustained FAFs (25 fractures) with a mean age of 11 (Range: 10 mo to 18 years old) at the time of presentation. FAFs were most commonly noted in the upper extremity (n = 7) and lower extremity (n = 6). In total, 33% (n = 7) of patients with FAFs required orthopaedic surgical management, which was most commonly comprised of debridement (n = 6/7, 86%), and 14% (n = 1/7) of these patients required coordinated care with plastic and/or vascular surgery. Of the patients with FAFs, 52% (n = 11) had a minimum 90-d follow-up, and 48% (n = 10) had a minimum 2-year follow-up. Approximately 2 patients were readmitted within 90-d, while one patient required a reoperation within 2-years.

Over 25% of FAIs in pediatric patients result in FAFs. FAFs often present to pediatric trauma centers and the majority of these injuries occur in non-Caucasian males with government insurance. Most FAFs do not need orthopaedic surgical management; 14% of these injuries require subspecialty care by orthopaedic surgery, vascular surgery, or plastic surgery. Patients with FAFs also have lower ISS compared to patients who sustained FAIs without fracture. Thus, these patients should be treated at pediatric trauma centers with specialty care and additional research is needed to focus pre

Additional effort is needed to maintain follow-up and decrease the risk for read

| 1. | Leventhal JM, Gaither JR, Sege R. Hospitalizations due to firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Perkins C, Scannell B, Brighton B, Seymour R, Vanderhave K. Orthopaedic firearm injuries in children and adolescents: An eight-year experience at a major urban trauma center. Injury. 2016;47:173-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Blumberg TJ, DeFrancesco CJ, Miller DJ, Pandya NK, Flynn JM, Baldwin KD. Firearm-associated Fractures in Children and Adolescents: Trends in the United States 2003-2012. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38:e387-e392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Allareddy V, Nalliah RP, Rampa S, Kim MK, Allareddy V. Firearm related injuries amongst children: estimates from the nationwide emergency department sample. Injury. 2012;43:2051-2054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Srinivasan S, Mannix R, Lee LK. Epidemiology of paediatric firearm injuries in the USA, 2001-2010. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:331-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | DiScala C, Sege R. Outcomes in children and young adults who are hospitalized for firearms-related injuries. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1306-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Berg RJ, Okoye O, Inaba K, Konstantinidis A, Branco B, Meisel E, Barmparas G, Demetriades D. Extremity firearm trauma: the impact of injury pattern on clinical outcomes. Am Surg. 2012;78:1383-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen AD, Ultee KHJ, Bucknor A, Chattha A, Ruan QZ, Lee BT, Afshar S, Lin SJ. A Study of 39,478 Firearm Injuries in the Pediatric Population: Trends over Time and Disparities in Flap Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Karkenny, AJ, Morris J, Hamm JK, Maguire K, Toro J, Stone M, Fornari E, Schulz JF. Follow-up and Functional Outcomes of Pediatric Patients with Firearm Injuries to the Extremities. Pediatrics. 2018;141:1. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Kalesan B, Vasan S, Mobily ME, Villarreal MD, Hlavacek P, Teperman S, Fagan JA, Galea S. State-specific, racial and ethnic heterogeneity in trends of firearm-related fatality rates in the USA from 2000 to 2010. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Arslan H, Subasi M, Kesemenli C, Kapukaya A, Necmioğlu S, Kayikçi C. Problem fractures associated with gunshot wounds in children. Injury. 2002;33:743-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Letts RM, Miller D. Gunshot wounds of the extremities in children. J Trauma. 1976;16:807-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Naranje SM, Gilbert SR, Stewart MG, Rush JK, Bleakney CA, McKay JE, Warner WC Jr, Kelly DM, Sawyer JR. Gunshot-associated Fractures in Children and Adolescents Treated at Two Level 1 Pediatric Trauma Centers. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Pediatric Spine Study Group; International Perthes Study Group; SCFE Longitudinal International Prospective Registry; American Academy of Pediatrics; Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America; American Orthopaedic Association Emerging Leaders Program; American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; Alpha Omega Alpha Medical Honor Society.

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mayr J S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY