Published online Jan 21, 2026. doi: 10.5315/wjh.v12.i1.115355

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: December 29, 2025

Published online: January 21, 2026

Processing time: 96 Days and 18.9 Hours

Hereditary spherocytosis (HS) is the most common congenital hemolytic anemia in children, and splenectomy remains the standard treatment. However, posto

To identify risk factors for PST in children with HS after splenectomy and develop a predictive nomogram model.

We retrospectively analyzed 230 children with HS who underwent total sple

Among 230 patients, 158 (68.7%) developed PST. Univariate analysis showed associations with preoperative hemoglobin < 90 g/L (P = 0.03), reticulocyte > 6% (P = 0.001), total bilirubin > 34 μmol/L (P = 0.04), preoperative platelet count < 150 × 109/L (P = 0.02), and transfusion ≥ 10 mL/kg (P = 0.01). Multivariate regression identified reticulocyte > 6% [odds ratios (OR) = 2.46, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.35-4.48, P = 0.003], preoperative platelet count < 150 × 109/L (OR = 1.95, 95%CI: 1.12-3.39, P = 0.02), and transfusion ≥ 10 mL/kg (OR = 1.88, 95%CI: 1.09-3.24, P = 0.02) as independent predictors. The nomogram achieved an area under the curve of 0.92 (95%CI: 0.87-0.96), with good calibration and clinical net benefit across thresholds of 0.2-0.7.

PST is frequent after splenectomy in pediatric HS. The nomogram integrating reticulocyte percentage, platelet count, and transfusion volume provides an accurate and clinically useful tool for risk prediction and individualized perioperative management.

Core Tip: Postoperative thrombocytosis is a frequent complication following splenectomy in children with hereditary spherocytosis, yet its predictors remain unclear. In this large cohort of 230 patients, we identified elevated reticulocyte count, low preoperative platelet count, and higher transfusion volume as independent risk factors. Based on these parameters, we developed and validated a nomogram with excellent discriminative power, good calibration, and strong clinical utility. This practical tool enables early risk stratification and individualized perioperative management, potentially reducing thrombotic complications and improving outcomes in pediatric hereditary spherocytosis patients undergoing splenectomy.

- Citation: Zhang T, Li ZC, Pan ZB, Qi SQ, Tang R. Nomogram-based prediction of post-splenectomy thrombocytosis in children with hereditary spherocytosis. World J Hematol 2026; 12(1): 115355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6204/full/v12/i1/115355.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5315/wjh.v12.i1.115355

Hereditary spherocytosis (HS) is one of the most common inherited hemolytic anemias, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1 in 2000 individuals in Western countries, while being relatively rare in Asia; however, the diagnosis rate has been increasing in recent years[1,2]. The pathogenesis is associated with mutations in genes encoding red blood cell membrane skeleton proteins (e.g., ankyrin, spectrin, and band 3), which lead to increased erythrocyte fragility and shortened lifespan, thereby resulting in chronic hemolysis[3,4].

The clinical manifestations of HS are highly heterogeneous. Patients with mild disease may remain asymptomatic or present only with mild anemia, whereas severe cases often exhibit overt hemolytic jaundice, splenomegaly, and complications such as cholelithiasis[5,6]. At present, splenectomy remains one of the most important therapeutic strategies for children with moderate to severe HS, as it can significantly improve anemia and hemolysis, thereby enhancing quality of life[7,8]. Nevertheless, the loss of splenic function may induce postoperative thrombocytosis (PST), a common com

Previous studies have reported that the incidence of PST in children ranges from 60% to 80%. Although most cases are mild to moderate, a subset of patients may experience marked thrombocytosis (> 1000 × 109/L), which substantially increases the risk of portal vein thrombosis, cerebral thrombosis, and cardiovascular complications[10-12]. The un

To date, systematic investigations on PST following splenectomy in HS patients remain limited, particularly studies establishing risk prediction models based on clinical parameters[15]. The present study aimed to bridge this gap by analyzing a large single-center cohort of 230 pediatric HS patients who underwent splenectomy to identify independent risk factors and develop a nomogram for predicting PST probability. This model seeks to facilitate preoperative risk assessment and individualized management to prevent thrombotic complications after splenectomy.

A retrospective study was conducted on 230 children diagnosed with HS who underwent total splenectomy at Anhui Provincial Children’s Hospital from November 2018 to September 2025. Patients were divided into two groups according to the occurrence of PST: The thrombocytosis group (n = 158) and the normal platelet group (n = 72). Inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosis of HS confirmed by clinical manifestations, family history, osmotic fragility test, eosin-5’-maleimide binding test, and genetic testing when available; (2) Underwent splenectomy with complete perioperative data; and (3) Pos

General clinical characteristics were collected, including age, sex, intraoperative blood loss, and transfusion volume. Preoperative hematological parameters were recorded, including hemoglobin, platelet count, reticulocyte percentage, total bilirubin, and other relevant biochemical indices. Postoperative platelet parameters were measured at 6-10 days after surgery, including platelet count, mean platelet volume (MPV), plateletcrit, and platelet distribution width. This time frame was selected based on prior pediatric hematology studies showing that platelet elevation peaks within one week after splenectomy.

PST was defined as a platelet count ≥ 500 × 109/L within 6-10 days postoperatively, consistent with prior literature and pediatric hematology standards. The highest value within this period was used for analysis to reduce inter-day variability.

Missing data were examined for each variable. When missingness was < 5%, complete-case analysis was applied; when ≥ 5%, multiple imputation using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method was performed. Before model construction, all continuous variables were checked for nonlinearity using restricted cubic splines, and multicollinearity was assessed by variance inflation factor, with variance inflation factor > 5 considered indicative of collinearity.

All statistical analyses were independently reviewed by a biomedical statistician prior to submission. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using independent-sample t tests. Categorical variables were expressed as n (%), and comparisons were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Univariate logistic regression was applied to identify potential risk factors for PST, and variables with statistical significance were entered into multivariate logistic regression to determine independent predictors. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Independent predictors identified from multivariate analysis were incorporated into a nomogram prediction model using R software (version 4.0.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Model performance was evaluated by: (1) Discrimination: Assessed by receiver operating characteristic curve and area under the curve (AUC); (2) Ca

A total of 230 children with HS who underwent total splenectomy were included, of whom 158 (68.7%) developed PST and 72 (31.3%) remained within the normal platelet range. Baseline characteristics including age, sex, body mass index, preoperative hemoglobin, history of transfusion, family history, and splenic size were comparable between the two groups (all P > 0.05). However, the thrombocytosis group had a higher mean reticulocyte percentage (5.6% ± 1.8% vs 4.9% ± 1.6%, P = 0.03), suggesting enhanced marrow compensatory activity (Table 1).

| Variables | Thrombocytosis group (n = 158) | Normal platelet group (n = 72) | P value |

| Age (years) | 9.4 ± 2.3 | 9.1 ± 2.5 | 0.36 |

| Sex (male/female) | 90/68 | 42/30 | 0.88 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 18.9 ± 2.4 | 18.6 ± 2.2 | 0.42 |

| Preoperative Hb (g/L) | 92.1 ± 11.6 | 94.5 ± 12.2 | 0.27 |

| Reticulocyte (%) | 5.6 ± 1.8 | 4.9 ± 1.6 | 0.03 |

| History of transfusion, n (%) | 45 (28.5) | 17 (23.6) | 0.41 |

| Splenic size (longest diameter, cm) | 15.2 ± 2.1 | 14.9 ± 2.3 | 0.49 |

At postoperative days 6-10, the thrombocytosis group showed markedly elevated platelet counts [(689.2 ± 103.5) × 109/L vs (342.8 ± 84.6) × 109/L, P < 0.001]. MPV was significantly lower (9.1 ± 1.2 fL vs 10.2 ± 1.3 fL, P < 0.001), and plateletcrit was significantly higher (0.35% ± 0.07% vs 0.21% ± 0.05%, P < 0.001). Platelet distribution width was slightly increased in the thrombocytosis group (14.8 ± 2.1 vs 13.9 ± 1.9, P = 0.04) (Table 2).

| Variables | Thrombocytosis group (n = 158) | Normal platelet group (n = 72) | P value |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 689.2 ± 103.5 | 342.8 ± 84.6 | < 0.001 |

| Mean platelet volume (fL) | 9.1 ± 1.2 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| Plateletcrit (%) | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| Platelet distribution width (%) | 14.8 ± 2.1 | 13.9 ± 1.9 | 0.04 |

Univariate analysis identified several factors significantly associated with PST, including preoperative hemoglobin <

| Variables | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Reticulocyte (%) | 1.42 | 1.11-1.83 | 0.004 |

| Preoperative platelet count | 1.27 | 1.08-1.56 | 0.02 |

| Mean platelet volume | 0.81 | 0.69-0.95 | 0.01 |

| Transfusion volume | 1.35 | 1.05-1.72 | 0.03 |

| Splenic size (cm) | 1.10 | 0.92-1.32 | 0.18 |

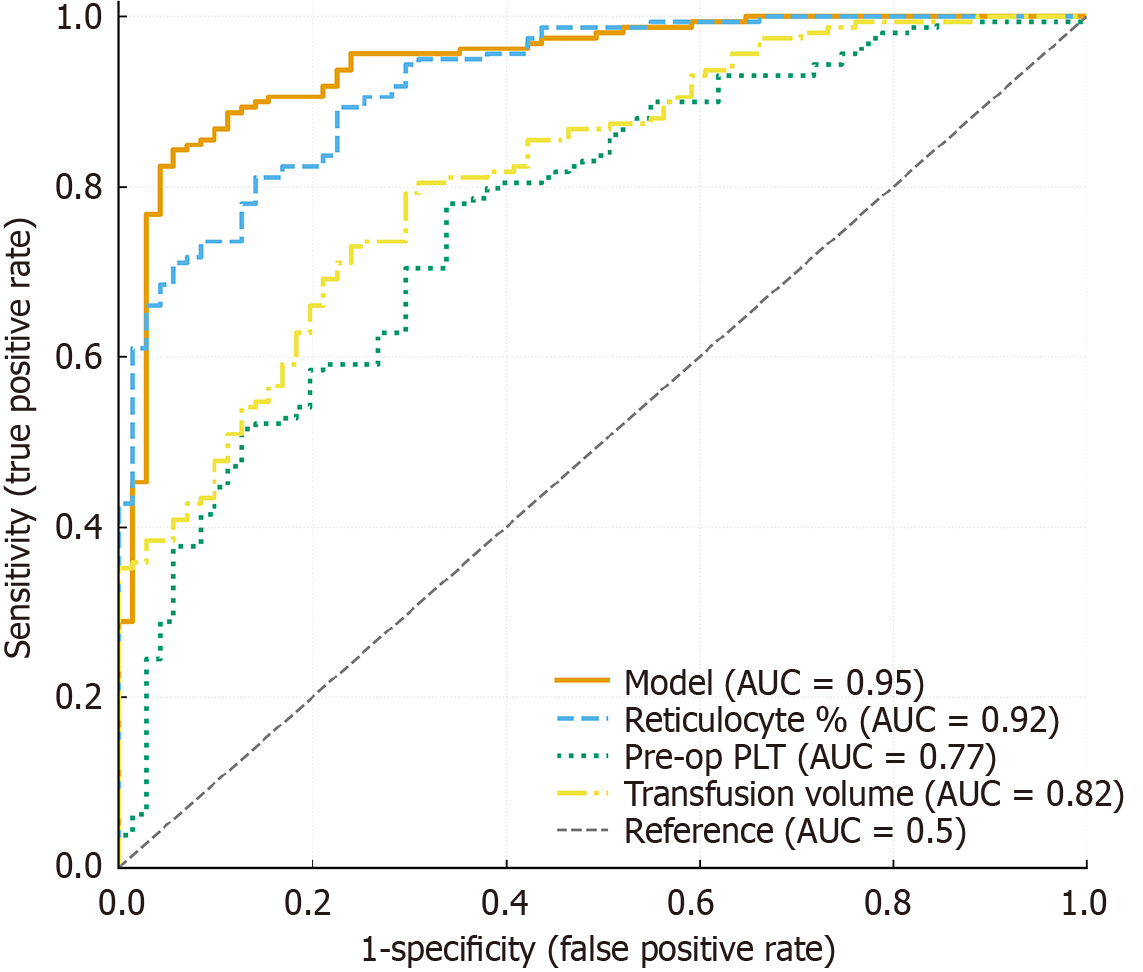

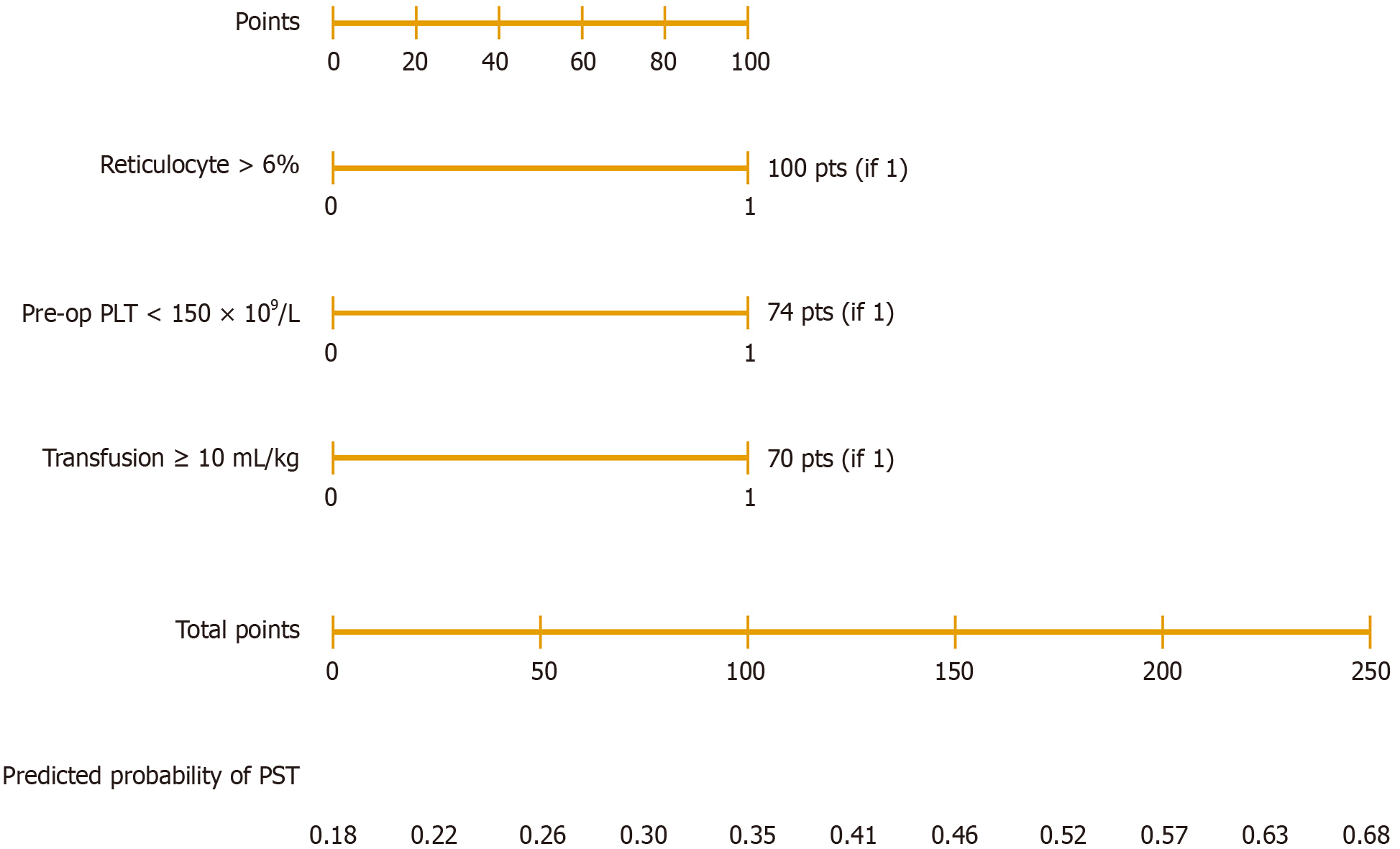

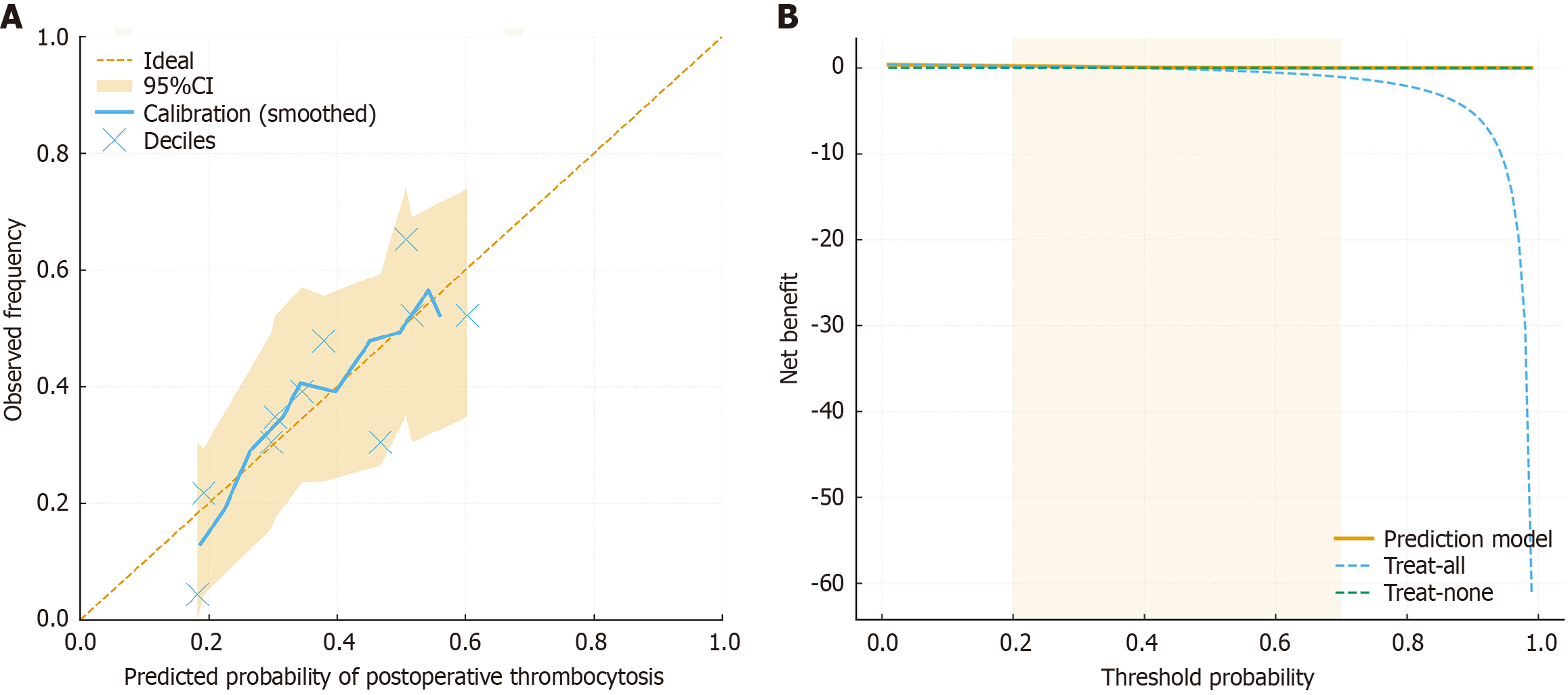

The discriminative performance of the nomogram model was first evaluated using receiver operating characteristic analysis. The model demonstrated excellent discrimination, with an AUC of 0.92 (95%CI: 0.87-0.96), which outperformed all individual predictors (reticulocyte AUC = 0.79, preoperative platelet count AUC = 0.76, transfusion AUC = 0.78, MPV AUC = 0.73; all P < 0.01) (Table 4, Figure 1). Based on the independent predictors identified by multivariate logistic re

| Predictors | AUC | 95%CI | P value |

| Reticulocyte (%) | 0.79 | 0.73-0.85 | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative platelet count | 0.76 | 0.69-0.83 | 0.002 |

| Transfusion volume | 0.78 | 0.72-0.84 | 0.001 |

| MPV | 0.73 | 0.66-0.80 | 0.004 |

| Combined model | 0.92 | 0.87-0.96 | < 0.001 |

The present study demonstrated that the incidence of PST among children with HS was 68.7%, which is consistent with previously reported rates of 60%-80%[16,17]. Although PST in most children is transient, extreme elevations in platelet counts (> 1000 × 109/L) may lead to serious complications such as portal vein thrombosis, cerebrovascular events, and even pulmonary embolism[18,19]. Therefore, perioperative identification and prediction of high-risk patients is of paramount clinical importance. This study is the first to construct a visualized nomogram model specifically for pre

A lower preoperative platelet count suggests significant splenic sequestration of platelets. Removal of the spleen abolishes this trapping effect, resulting in an abrupt “rebound” thrombocytosis, consistent with findings in both pediatric and adult studies[22,23]. Transfusion ≥ 10 mL/kg likely contributes through inflammatory mediator release, transient hemodynamic shifts, and stimulation of hematopoietic cytokines such as interleukin-6 and thrombopoietin, which en

The nomogram achieved an AUC of 0.92, indicating outstanding discrimination, while the calibration curve showed close agreement between predicted and observed risks. The DCA demonstrated net benefit across a clinically meaningful probability range (0.2-0.7), confirming that using this model to guide monitoring or prophylaxis decisions would improve patient outcomes compared with treating all or none. Clinically, the model allows stratified management: (1) High-risk patients can undergo intensified postoperative platelet monitoring and receive prophylactic antithrombotic therapy (e.g., low-dose aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin) as indicated[25]; and (2) Low-risk patients can avoid unnecessary prophylaxis, minimizing bleeding risk and drug-related adverse effects. Compared with prior studies that only explored single-factor associations, our work integrates multivariable predictors into a validated, easy-to-use graphical tool, bridging the translational gap between statistical modeling and bedside decision-making.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this was a single-center retrospective analysis, and potential selection bias cannot be fully excluded. Second, genetic subtyping and inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., interleukin-6, throm

In summary, PST is common among children with HS, occurring in approximately two-thirds of patients. Elevated reticulocyte count, low preoperative platelet count, and high transfusion volume were identified as independent predictors of PST. The nomogram model incorporating these variables demonstrated excellent discrimination, calibration, and clinical usefulness, providing a practical and visualized tool for individualized perioperative risk prediction. Early recognition of high-risk patients enables clinicians to optimize monitoring and preventive strategies, thereby reducing thrombotic complications and improving surgical outcomes in pediatric HS.

The authors thank the biomedical statistician for the independent review of statistical methods and analyses. We also appreciate the contributions of the nursing staff and laboratory technicians at Anhui Provincial Children’s Hospital for their assistance with patient care and data collection.

| 1. | Nakatsu Y, Yamada K, Ueda J, Onogi A, Ables GP, Nishibori M, Hata H, Takada A, Sawai K, Tanabe Y, Morita M, Daikohara M, Watanabe T. Genetic polymorphisms and antiviral activity in the bovine MX1 gene. Anim Genet. 2004;35:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Eber S, Lux SE. Hereditary spherocytosis--defects in proteins that connect the membrane skeleton to the lipid bilayer. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:118-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Perrotta S, Gallagher PG, Mohandas N. Hereditary spherocytosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1411-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Da Costa L, Galimand J, Fenneteau O, Mohandas N. Hereditary spherocytosis, elliptocytosis, and other red cell membrane disorders. Blood Rev. 2013;27:167-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Crary SE, Buchanan GR. Vascular complications after splenectomy for hematologic disorders. Blood. 2009;114:2861-2868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Passon RG, Howard TA, Zimmerman SA, Schultz WH, Ware RE. Influence of bilirubin uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A promoter polymorphisms on serum bilirubin levels and cholelithiasis in children with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:448-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Laverdière C, Cheung NK, Kushner BH, Kramer K, Modak S, LaQuaglia MP, Wolden S, Ness KK, Gurney JG, Sklar CA. Long-term complications in survivors of advanced stage neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:324-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iolascon A, Andolfo I, Barcellini W, Corcione F, Garçon L, De Franceschi L, Pignata C, Graziadei G, Pospisilova D, Rees DC, de Montalembert M, Rivella S, Gambale A, Russo R, Ribeiro L, Vives-Corrons J, Martinez PA, Kattamis A, Gulbis B, Cappellini MD, Roberts I, Tamary H; Working Study Group on Red Cells and Iron of the EHA. Recommendations regarding splenectomy in hereditary hemolytic anemias. Haematologica. 2017;102:1304-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Das A, Bansal D, Ahluwalia J, Das R, Rohit MK, Attri SV, Trehan A, Marwaha RK. Risk factors for thromboembolism and pulmonary artery hypertension following splenectomy in children with hereditary spherocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bader-Meunier B, Gauthier F, Archambaud F, Cynober T, Miélot F, Dommergues JP, Warszawski J, Mohandas N, Tchernia G. Long-term evaluation of the beneficial effect of subtotal splenectomy for management of hereditary spherocytosis. Blood. 2001;97:399-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Guizzetti L. Total versus partial splenectomy in pediatric hereditary spherocytosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1713-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Englum BR, Rothman J, Leonard S, Reiter A, Thornburg C, Brindle M, Wright N, Heeney MM, Jason Smithers C, Brown RL, Kalfa T, Langer JC, Cada M, Oldham KT, Scott JP, St Peter SD, Sharma M, Davidoff AM, Nottage K, Bernabe K, Wilson DB, Dutta S, Glader B, Crary SE, Dassinger MS, Dunbar L, Islam S, Kumar M, Rescorla F, Bruch S, Campbell A, Austin M, Sidonio R, Blakely ML, Rice HE; Splenectomy in Congenital Hemolytic Anemia Consortium. Hematologic outcomes after total splenectomy and partial splenectomy for congenital hemolytic anemia. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hall BJ, Reiter AJ, Englum BR, Rothman JA, Rice HE. Long-term hematologic and clinical outcomes of splenectomy in children with hereditary spherocytosis and sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Khan PN, Nair RJ, Olivares J, Tingle LE, Li Z. Postsplenectomy reactive thrombocytosis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2009;22:9-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Burr M, Wittman P. The influence of a therapy dog on a pediatric therapy organization: A mini ethnography. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;38:101083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sun L, Du J, Li Y. A new method for dividing the scopes and priorities of air pollution control based on environmental justice. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28:12858-12869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu Y, Liao L, Lin F. The diagnostic protocol for hereditary spherocytosis-2021 update. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35:e24034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zvizdic Z, Kovacevic A, Milisic E, Jonuzi A, Vranic S. Clinical course and short-term outcome of postsplenectomy reactive thrombocytosis in children without myeloproliferative disorders: A single institutional experience from a developing country. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Attina' G, Triarico S, Romano A, Maurizi P, Mastrangelo S, Ruggiero A. Role of Partial Splenectomy in Hematologic Childhood Disorders. Pathogens. 2021;10:1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lin YK, Cai XR, Hong HJ, Chen JZ, Chen YL, Du Q. Risk factors of portal vein system thrombosis after splenectomy: a meta-analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2023;93:2806-2819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Heldahl MG, Eksveen B, Bunne M. Cochlear implants in eight children with Down Syndrome - Auditory performance and challenges in assessment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;126:109636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stringer MD, Lucas N. Thrombocytosis and portal vein thrombosis after splenectomy for paediatric haemolytic disorders: How should they be managed? J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54:1184-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim EJ, Kim YE, Jang JH, Cho EH, Na DL, Seo SW, Jung NY, Jeong JH, Kwon JC, Park KH, Park KW, Lee JH, Roh JH, Kim HJ, Yoon SJ, Choi SH, Jang JW, Ki CS, Kim SH. Analysis of frontotemporal dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and other dementia-related genes in 107 Korean patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;72:186.e1-186.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Batista MV, Ulrich J, Costa L, Ribeiro LA. Multiple Primary Malignancies in Head and Neck Cancer: A University Hospital Experience Over a Five-Year Period. Cureus. 2021;13:e17349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3515] [Cited by in RCA: 3858] [Article Influence: 192.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ. 2015;350:g7594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1604] [Cited by in RCA: 2656] [Article Influence: 241.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Boccatonda A, Gentilini S, Zanata E, Simion C, Serra C, Simioni P, Piscaglia F, Campello E, Ageno W. Portal Vein Thrombosis: State-of-the-Art Review. J Clin Med. 2024;13:1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/