Published online Feb 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.115188

Revised: October 28, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: February 18, 2026

Processing time: 117 Days and 9.7 Hours

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is increasingly performed in elderly patients with osteoarthritis, yet preoperative frailty is associated with adverse outcomes. Limi

To evaluate the association between preoperative frailty, assessed by the modified Frailty Index, and postoperative complications, hospital length of stay (LOS), 90-day readmission rates, and 1-year functional recovery in elderly Pakistani patients undergoing primary TKA.

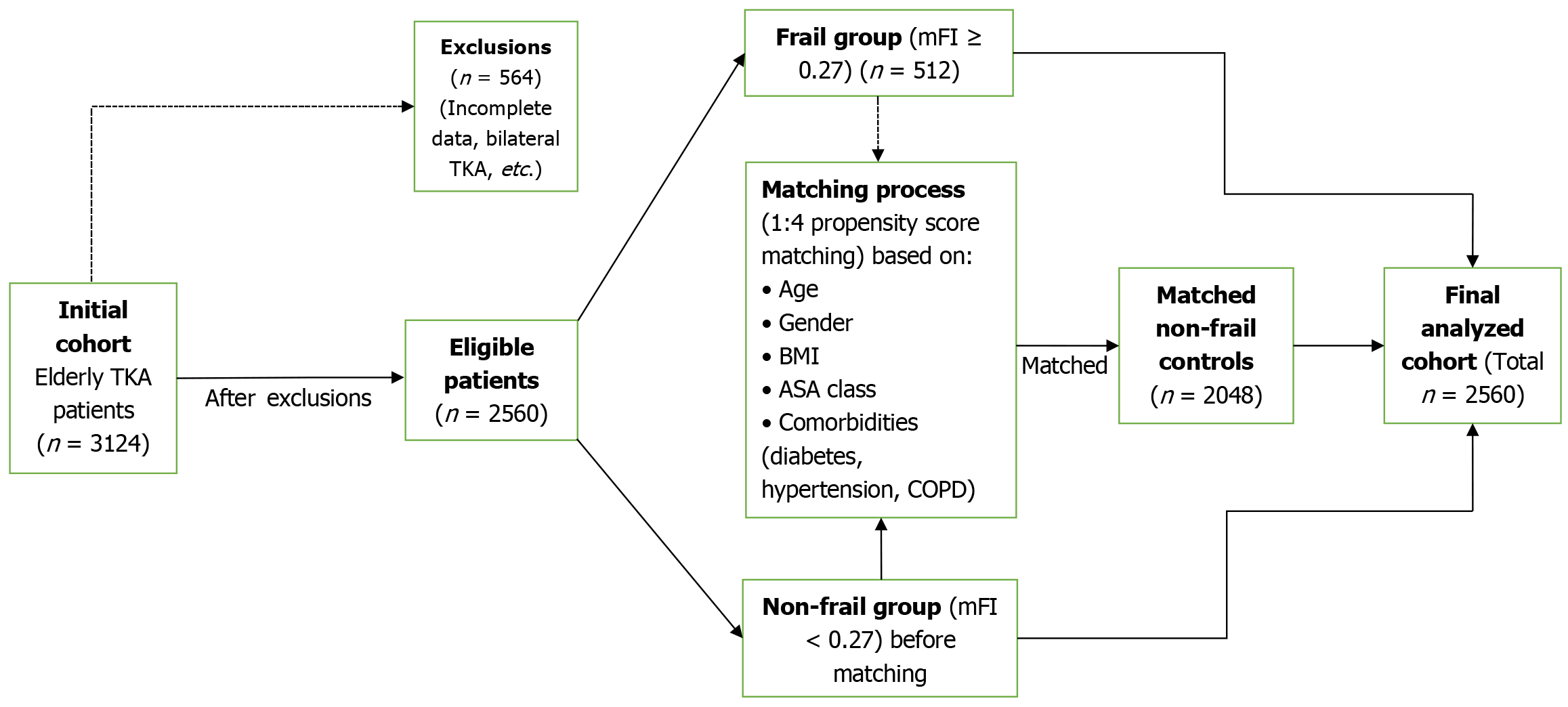

This retrospective cohort study analyzed de-identified records from Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur, Pakistan (from January 2015 to September 2025). Patients aged ≥ 65 years with primary unilateral TKA for osteoarthritis were included. Frail patients (n = 512) were propensity score-matched 1:4 to non-frail controls (n = 2048) using nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.1. Propensity score estimation followed established methodological standards. Logistic regression, t-tests, χ2 tests, and Kaplan-Meier analyses were used, with P < 0.05 denoting significance. Sensitivity analyses addressed alternative modified Frailty Index thresholds, matching overlap and missing data.

Post-matching, groups were balanced. Frail patients had higher composite complications [21.1% vs 9.2%; adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 2.61, 95%CI: 2.05-3.32; P < 0.001], including surgical site infection (OR = 3.12, 95%CI: 2.18-4.46; P < 0.001), deep vein thrombosis (OR = 2.85, 95%CI: 1.92-4.23; P < 0.001), and pulmonary embolism (OR = 4.02, 95%CI: 2.45-6.59; P < 0.001). LOS was prolonged (5.6 ± 1.9 days vs 3.9 ± 1.5 days; P < 0.001), readmissions increased (17% vs 4%; OR = 4.74, 95%CI: 3.56-6.31; P < 0.001), and 1-year Knee Society Score was lower (75.5 ± 10.2 vs 85.1 ± 8.1; P < 0.001), with smaller delta Knee Society Score (30.3 ± 11.4 vs 39.0 ± 10.2; P < 0.001), approaching the minimal clinically important difference of approximately 9 points. Sensitivity analyses confirmed robustness.

Preoperative frailty is associated with increased complications, extended LOS, higher readmissions, and impaired functional recovery in elderly TKA patients in this Pakistani cohort. These findings are most directly applicable to tertiary care centers in Pakistan with comparable patient complexity and resource availability. Extrapolation to primary care or markedly different healthcare systems requires further validation. Routine frailty screening may aid risk stratification and perioperative management in similar settings, considering regional challenges such as high tuberculosis prevalence.

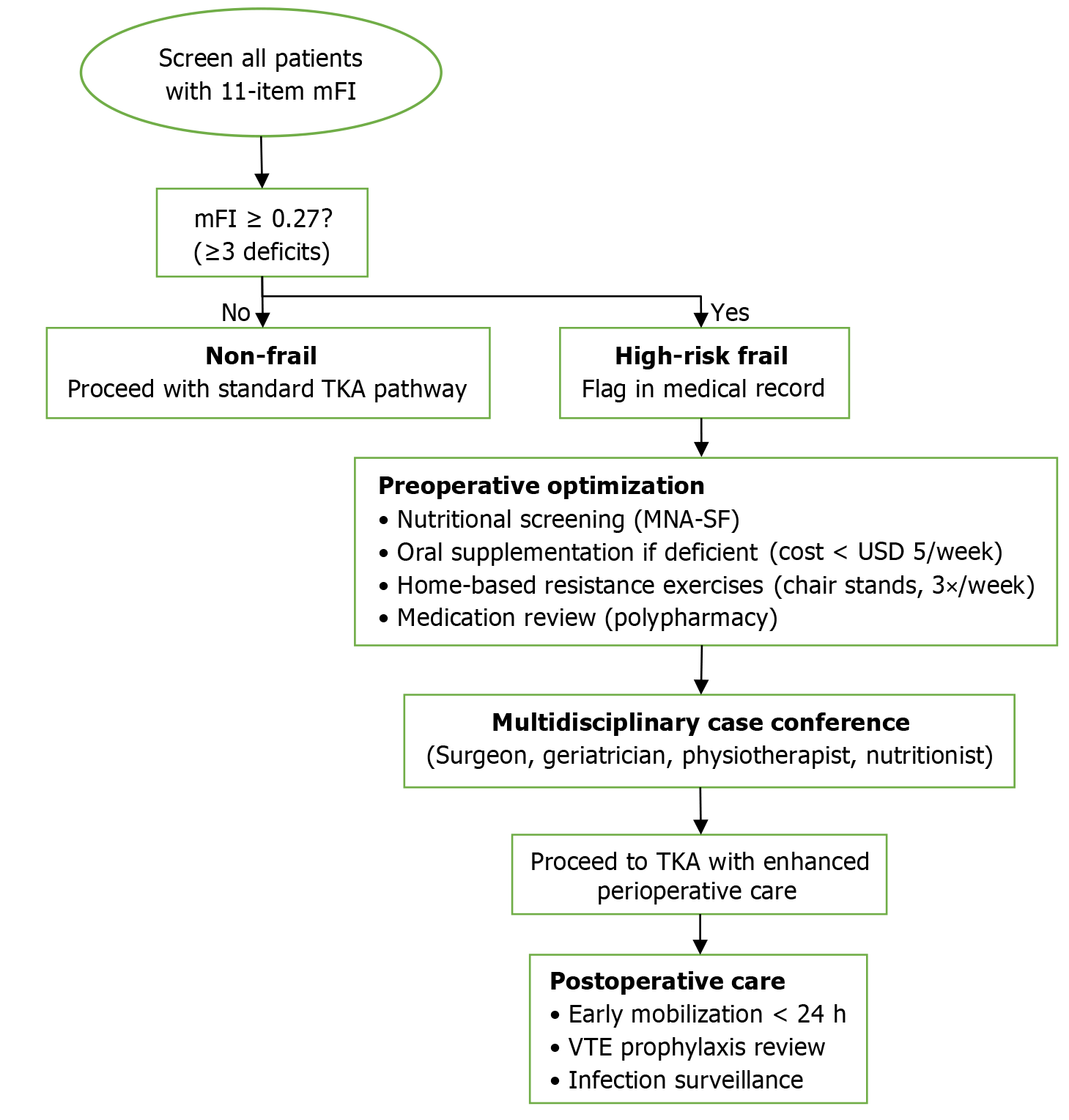

Core Tip: This retrospective cohort study from Pakistan demonstrates that preoperative frailty, assessed by the modified Frailty Index, significantly increases postoperative complications, hospital length of stay, and 90-day readmissions while impairing 1-year functional recovery in elderly patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Findings are most applicable to tertiary referral centers in Pakistan. Routine frailty screening could enhance risk stratification and perioperative management in resource-limited settings, addressing challenges like high tuberculosis prevalence to optimize outcomes and reduce healthcare burdens. A practical pathway includes: (1) The modified Frailty Index ≥ 0.27 to flag high-risk; (2) Initiate low-cost prehabilitation (nutritional screening/supplementation, home-based resistance exercises, medication review); and (3) Multidisciplinary review before surgery.

- Citation: Yasin MB, Raheel M, Ahmed MM, Ashfaq S, Asim HS, Rauf MQ, Fahim R, Chhetri R. Impact of preoperative frailty on complications, readmissions, and functional recovery following total knee arthroplasty in elderly patients. World J Orthop 2026; 17(2): 115188

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i2/115188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.115188

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a highly effective surgical intervention for end-stage knee osteoarthritis, particularly in the elderly population, where it aims to alleviate pain, restore function, and improve quality of life[1]. With global aging trends, the demand for TKA among individuals aged 65 years and older has surged, with projections indicating a 129% increase in primary TKA procedures in the United States by 2030[2]. However, elderly patients often present with multifaceted vulnerabilities, including frailty, a multidimensional syndrome characterized by decreased physiological reserves, increased susceptibility to stressors, and diminished resilience[3,4]. Frailty has been increasingly recognized as a critical preoperative risk factor in orthopedic surgery, associated with higher rates of postoperative complications, prolonged hospital stays, delayed functional recovery, and increased healthcare utilization[5]. A recent study confirmed frailty as a robust predictor of adverse arthroplasty outcomes across diverse populations[6].

In resource-constrained settings like Pakistan, where osteoarthritis prevalence is high[7], TKA outcomes can be particularly influenced by preoperative health status. A systematic review of frailty in arthroplasty highlights a paucity of data from South Asia, with most evidence derived from Western cohorts[5]. While studies from India have explored frailty in orthopedic surgery[8,9], localized evidence from Pakistan is limited, necessitating region-specific research to guide clinical practice. This gap is particularly relevant given Pakistan's unique epidemiological profile, including high burdens of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), which may exacerbate complication risks in frail patients. Common frailty tools, such as the modified Frailty Index (mFI), offer a practical means to stratify risk by evaluating comorbidities and functional deficits[10]. Prior studies from Western cohorts have linked frailty to adverse events like infections, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and reduced knee function scores post-TKA[11,12]. This study aimed to investigate the association of preoperative frailty, as assessed by the 11-item mFI, with: (1) Postoperative complications; (2) Hospital length of stay (LOS) and 90-day readmission rates; and (3) Functional recovery at 1-year follow-up in elderly patients undergoing TKA at a major Pakistani tertiary care hospital.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted using de-identified electronic medical records from the Bahawal Victoria Hospital (BVH) database in Bahawalpur, Pakistan, spanning from January 2015 to September 2025. BVH is a leading tertiary care institution that maintains a comprehensive registry of orthopedic procedures aligned with the Pakistan National Joint Registry (PNJR) standards[13]. The study was approved by the BVH Institutional Review Board (No. 2025-ORTH-012), with a waiver of informed consent granted due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of anonymized data. This waiver was justified on the basis that the research involved no more than minimal risk to subjects, the waiver would not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects, and the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver. Approval permitted analysis of existing records, including those up to September 2025. All patient privacy rights were observed, and no patient names, initials, or hospital numbers were included in the text, figures, or tables.

Patients aged ≥ 65 years who underwent primary unilateral TKA for osteoarthritis were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision code M17 and Current Procedural Terminology code 27447. This represented approximately 80% of all elderly TKA cases performed at the institution during the study period, with the remainder excluded primarily due to bilateral procedures or revisions. Exclusion criteria included bilateral TKA (n = 140), revision procedures (n = 60), acute trauma cases (n = 40), and incomplete frailty or outcome data (n = 324; defined as > 20% missing variables for mFI components or primary outcomes). Patterns of excluded cases showed no significant differences in age or gender (P > 0.05). Ethnic background and urban/rural status were extracted from demographic fields where available. The cohort from this tertiary referral center may represent patients with more complex pathology or higher comorbidity burdens compared to those in general or rural settings, potentially introducing selection bias, which is addressed in the limitations.

Preoperative frailty was assessed using the 11-item mFI, derived from chart-reviewed variables (Supplementary Table 1). The mFI score was calculated as the number of deficits divided by 11, with ≥ 0.27 (≥ 3 deficits) classifying patients as frail, consistent with validated thresholds for the 11-item mFI in arthroplasty[14,15]. This threshold was selected based on validated cutoffs in orthopedic and arthroplasty literature, demonstrating predictive utility for adverse outcomes in TKA cohorts using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data[14,15]. Sensitivity analyses were performed using alternative thresholds (e.g., ≥ 0.36 or binary: 0 vs ≥ 1 deficits) to assess result stability.

Frail patients were matched 1:4 to non-frail controls using propensity score matching (PSM) to minimize confounding. Propensity scores were estimated via logistic regression including covariates: (1) Age (continuous); (2) Gender; (3) Body mass index (continuous); (4) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification; (5) Diabetes; (6) Hypertension; and (7) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These covariates were selected based on their known prognostic relevance for frailty status and TKA outcomes. Matching was performed using nearest-neighbor method with a caliper of 0.1 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score, following established methodological guidance. The 1:4 ratio was chosen to maximize statistical power while maintaining match quality. Pre-matching, frail patients had higher rates of unmatched mFI components (e.g., functional dependence: 25% vs 5%). Balance was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMDs), with all post-matching SMDs < 0.1, indicating excellent balance (Table 1). A Supplementary Figure 1 illustrating propensity score overlap (common support) is provided. After matching, the cohort included 512 frail patients and 2048 non-frail controls (total n = 2560). A pre-specified power analysis, assuming a 15% complication rate difference based on prior studies (α = 0.05, 1:4 ratio), confirmed > 95% power; post-hoc analysis verified > 99%. Completeness of follow-up was high, with < 2% loss for 90-day outcomes and 6.5% overall for 1-year functional assessments.

| Characteristic | Frail pre-match | Non-frail pre-match (n = 2512) | SMD pre-match | Frail post-match (n = 512) | Non-frail post-match (n = 2048) | SMD post-match |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 73.5 ± 5.5 | 71.2 ± 4.8 | 0.45 | 72.3 ± 5.1 | 72.1 ± 4.9 | 0.04 |

| Gender: Female (%) | 65.0 | 58.0 | 0.14 | 60.9 | 60.4 | 0.01 |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD) | 32.1 ± 4.2 | 29.8 ± 3.9 | 0.56 | 30.5 ± 4.0 | 30.4 ± 3.9 | 0.03 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists III and IV (%) | 45.0 | 25.0 | 0.42 | 30.1 | 29.0 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 55.0 | 35.0 | 0.41 | 40.6 | 40.1 | 0.01 |

| Hypertension (%) | 80.0 | 60.0 | 0.43 | 69.9 | 69.5 | 0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (%) | 30.0 | 15.0 | 0.35 | 19.9 | 20.0 | 0.00 |

Primary outcomes were postoperative complications within 90 days, defined as a composite of surgical site infection (SSI) (per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria as superficial or deep infection requiring intervention), DVT (confirmed by Doppler ultrasound), pulmonary embolism (confirmed by computed tomography angiography), periprosthetic fracture (radiographically confirmed), and pneumonia (expanded in sensitivity analyses). Complications were adjudicated by two independent reviewers blinded to frailty status, with discrepancies resolved by consensus to minimize information bias. Secondary outcomes included LOS (days from surgery to discharge), 90-day readmission rates (for TKA-related causes per International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, e.g., infection, thrombosis), and functional recovery assessed by the Knee Society Score (KSS) at 1-year follow-up [range 0-100, higher scores indicate better function; minimal clinically important difference (MCID) approximately 9 points][16,17]. Baseline KSS was extracted where available (92% of cohort) to calculate delta KSS (change from baseline). Time to achieve KSS ≥ 80 (representing good to excellent function)[17] was analyzed, with standardized follow-up at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months.

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± SD and compared using independent t-tests or Welch's t-test for unequal variances. Categorical variables were presented as n (%) and analyzed with χ2 tests. Odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI were calculated using logistic regression for binary outcomes, in the matched cohort, adjusted for residual confounders (history of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, functional dependence, ethnic group, urban/rural status). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used for time-to-event outcomes, with log-rank tests for group differences; competing risks were handled via Fine-Gray models in sensitivity analyses. Missing data (< 5% for key variables) was handled via complete case analysis, with multiple imputation (using mice package in R) tested in sensitivity (no alterations). To address matching overlap, sensitivity excluded cases outside common support. Additional sensitivities used alternative mFI thresholds (e.g., ≥ 0.36), stratification by procedure era (2015-2020 vs 2021-2025; interaction P > 0.05), unadjusted ORs from matched cohort, and multivariable regression on unmatched cohort to assess PSM robustness. All analyses were performed in R version 4.3.1. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. This study adheres to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines, with key items integrated throughout (e.g., variable definitions, confounding control, bias discussion).

A total of 3124 elderly TKA patients were initially identified; after exclusions and matching, 2560 were analyzed (Figure 1). Pre-matching characteristics showed imbalances (e.g., higher ASA III and IV in frail: 45% vs 25%, SMD = 0.42), which were resolved post-matching (all SMD < 0.1; Table 1). Demographic and comorbidity profiles were well-balanced between groups in the matched cohort, with the cohort predominantly urban (85%) and from diverse ethnic backgrounds (Urdu-speaking 45%, Sindhi 25%, Punjabi 15%, others 15%).

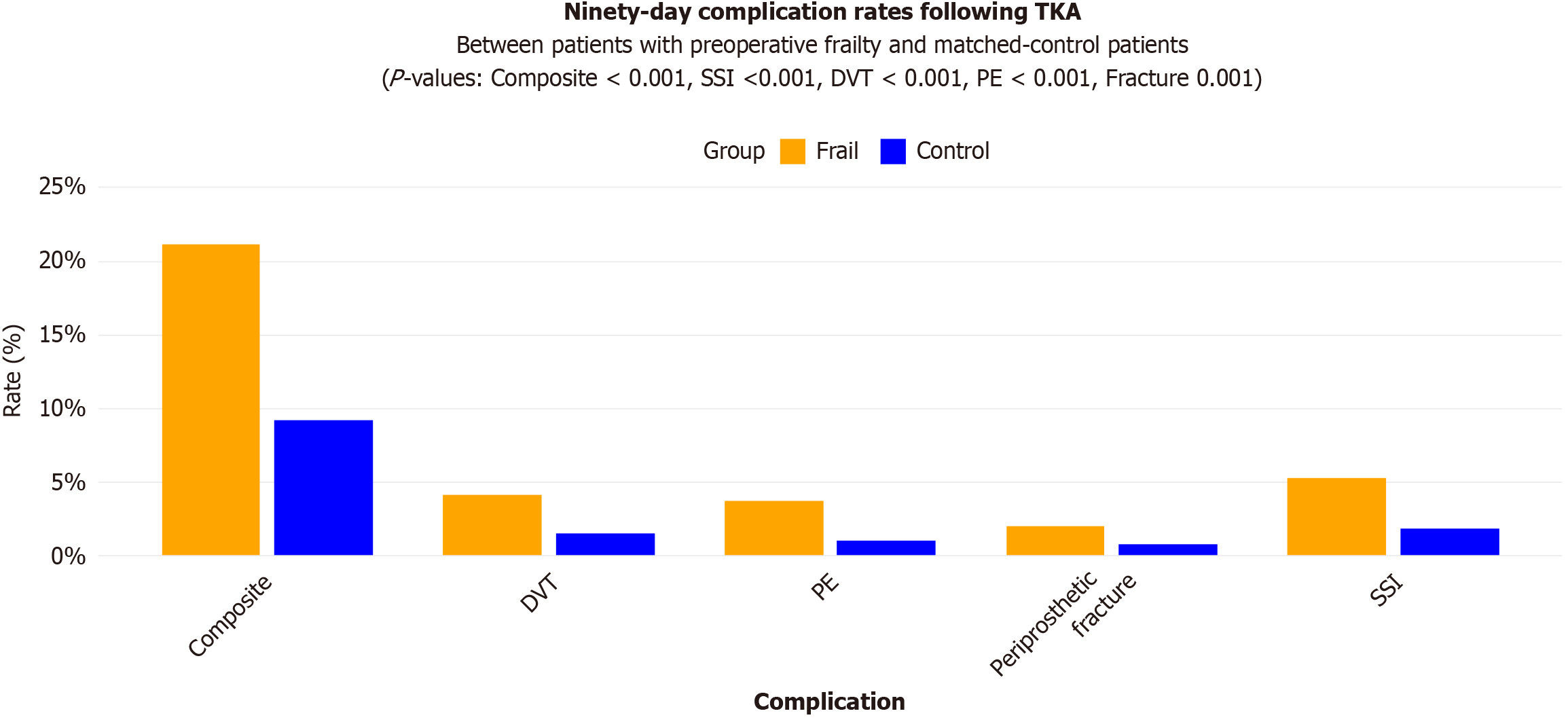

Postoperative complication rates were significantly higher in the frail group. The composite complication rate was 21.1% in frail patients vs 9.2% in non-frail patients (adjusted OR = 2.61; 95%CI: 2.05-3.32; P < 0.001). Specific complications included higher odds of SSI (OR = 3.12; 95%CI: 2.18-4.46; P < 0.001), DVT (OR = 2.85; 95%CI: 1.92-4.23; P < 0.001), and pulmonary embolism (OR = 4.02; 95%CI: 2.45-6.59; P < 0.001; Table 2 and Figure 2). Unadjusted ORs from the matched cohort were similar (e.g., composite OR = 2.64; 95%CI: 2.07-3.36), and multivariable regression on the unmatched cohort yielded comparable estimates (OR = 2.58; 95%CI: 2.01-3.30), supporting PSM effectiveness.

| Complication | Frailty (%) | Control (%) | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Composite | 21.1 | 9.2 | 2.61 | 2.05-3.32 | < 0.001 |

| Surgical site infection | 5.3 | 1.8 | 3.12 | 2.18-4.46 | < 0.001 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 4.1 | 1.5 | 2.85 | 1.92-4.23 | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3.7 | 1.0 | 4.02 | 2.45-6.59 | < 0.001 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 2.0 | 0.8 | 2.56 | 1.45-4.52 | 0.001 |

Healthcare utilization metrics showed prolonged LOS in frail patients (5.6 ± 1.9 days vs 3.9 ± 1.5 days; P < 0.001) and higher 90-day readmission rates (17% vs 4%; adjusted OR = 4.74; 95%CI: 3.56-6.31; P < 0.001; Table 3). Loss to follow-up for 90-day outcomes was minimal (< 2%).

| Utilization | Frailty | Control | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Readmission (%) | 17.0 | 4.2 | 4.74 | 3.56-6.31 | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay (days), mean ± SD) | 5.6 ± 1.9 | 3.9 ± 1.5 | - | - | < 0.001 |

Functional recovery at 1 year was inferior in the frail group, with mean KSS scores of 75.5 ± 10.2 vs 85.1 ± 8.1 (P < 0.001) and lower delta KSS (30.3 ± 11.4 vs 39.0 ± 10.2; P < 0.001; Table 4). The difference in delta KSS (8.7 points) approaches the MCID of approximately 9 points, suggesting clinical relevance. Baseline KSS was similar (45.2 ± 9.8 vs 46.1 ± 9.4; P = 0.312). Time to achieve KSS ≥ 80 was significantly delayed in frail patients (median 8 months vs 5 months; log-rank P < 0.001). Loss to follow-up for 1-year KSS was 8% in frail vs 5% in non-frail (P = 0.12); sensitivity analyses with imputation did not alter findings. Additional sensitivities using alternative mFI thresholds (e.g., ≥ 0.36) showed consistent associations, though with attenuated effect sizes.

| Outcome | Frailty (mean ± SD) | Control (mean ± SD) | P value |

| Baseline KSS | 45.2 ± 9.8 | 46.1 ± 9.4 | 0.312 |

| 1-year KSS | 75.5 ± 10.2 | 85.1 ± 8.1 | < 0.001 |

| Delta KSS | 30.3 ± 11.4 | 39.0 ± 10.2 | < 0.001 |

In this large retrospective cohort study from a Pakistani tertiary hospital, preoperative frailty, as measured by the mFI, was associated with significantly higher postoperative complications, extended LOS, increased readmissions, and poorer functional recovery in elderly TKA patients. These findings align with international literature, where frailty has been shown to predict adverse outcomes in arthroplasty[18,19]. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 47 studies similarly reported a 2.2-fold to 3.8-fold increased risk of major complications in frail patients undergoing joint replacement[5]. For instance, frail patients exhibited 2.61-fold increased odds of complications, mirroring reports from United States cohorts using similar indices[20-22]. However, complication rates (e.g., SSI 5.3%, DVT 4.1%) were higher than typical Western benchmarks (SSI approximately 1%-2%, DVT approximately 1%), potentially reflecting regional epidemiological challenges in Pakistan, a high-burden country for TB[23]. TB-related prosthetic joint infections, though rare (approximately 1% globally), pose diagnostic and management difficulties in resource-limited settings, where delayed presentation and limited access to advanced diagnostics may exacerbate risks in frail patients. The elevated complication rates may stem from frailty's impact on immune function, wound healing, and thromboembolic risk[24], compounded by local factors such as nutritional deficiencies or variable antibiotic prophylaxis protocols.

Prolonged LOS and readmissions in frail patients highlight resource implications, straining healthcare systems in low-income and middle-income countries where bed availability and surgical capacity are limited. In Pakistan, increased utilization could translate to substantial economic burdens, emphasizing the need for cost-effective interventions. Functional recovery, assessed via KSS, was notably delayed, consistent with studies linking frailty to muscle weakness and reduced mobility[25]. The delta KSS difference (8.7 points) approaches the MCID (approximately 9 points)[17], indicating clinically meaningful impairment that may affect quality of life and independence in this population.

These results are most directly generalizable to tertiary care centers in Pakistan with similar patient complexity, referral patterns, and resource availability. Caution is advised when extrapolating to primary care settings, rural hospitals, or healthcare systems with markedly different infrastructure, without further validation.

This underscores the need for targeted interventions, such as prehabilitation programs focusing on nutrition, exercise, and comorbidity optimization[22], tailored to regional constraints. To enhance clinical translation, we propose a practical frailty-based pathway (Figure 3): The mFI ≥ 0.27 to high-risk flag.

It including (1) Nutritional screening (e.g., mini nutritional assessment-short form) to oral supplementation if deficient (cost < United State Dollar 5/week); (2) Home-based resistance exercises (chair stands, ankle weights; 3 ×/week, supervised via phone); (3) Medication review for polypharmacy and fall risk; (4) Multidisciplinary case conference before surgery; and (5) Postoperative early mobilization with physiotherapy within 24 hours.

For example, addressing morbid obesity (prevalent in 50% of the cohort) in frail patients could mitigate risks of infection or mechanical failure, though multi-stage revisions remain challenging in resource-limited hospitals.

Limitations include the retrospective design, potential coding biases in hospital records (mitigated by dual review and blinding), lack of data on frailty severity, socioeconomic variables, surgical duration, or surgeon volume (not available in the registry), single-center setting limiting generalizability to rural or lower-resource Pakistani populations (patients at tertiary centers may have more complex cases, introducing selection bias), no long-term outcomes beyond 1 year (e.g., revision rates), residual confounding despite matching and adjustments (post-match SMDs < 0.1, but overlap may bias toward null), temporal changes over the 10-year period (addressed via stratification but not fully eliminated), selection bias from exclusions (18% dropout, analyzed and balanced between groups), information bias from retrospective data, and missing data handling (complete case with imputation sensitivity). The direction of biases likely attenuates associations (e.g., toward null). Potential publication bias in cited literature was not assessed; findings may not extend to other South Asian countries. No initial pre-specified power calculation, though updated. Strengths include the large sample from a PNJR-aligned registry, rigorous propensity matching with SMD assessment, and sensitivity analyses, and region-specific insights adding to sparse South Asian data.

Preoperative frailty assessment using the mFI is associated with higher risks of complications, prolonged hospitalization, and impaired functional recovery in elderly TKA patients at this Pakistani center. These findings are most applicable to tertiary referral centers in Pakistan and should not be over-generalized to primary care or dissimilar healthcare systems without validation. Integrating routine frailty screening could enhance risk stratification, patient counseling, and perioperative care in similar settings, particularly considering regional challenges like high TB prevalence and resource constraints, though findings may not generalize nationally. A structured, low-cost prehabilitation pathway – focusing on nutrition, home exercise, and medication review – offers a feasible implementation strategy. Prospective, multicenter studies are needed to validate these findings and evaluate the impact of frailty-targeted interventions on long-term outcomes.

| 1. | Noble PC, Gordon MJ, Weiss JM, Reddix RN, Conditt MA, Mathis KB. Does total knee replacement restore normal knee function? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Singh JA, Yu S, Chen L, Cleveland JD. Rates of Total Joint Replacement in the United States: Future Projections to 2020-2040 Using the National Inpatient Sample. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:1134-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 833] [Article Influence: 119.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1488] [Cited by in RCA: 1418] [Article Influence: 94.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4832] [Cited by in RCA: 6588] [Article Influence: 506.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu Y, Ying H, Yu D, Mao Y, Yan M, Li H, Zeng Y, Zhai Z. Positive Correlation Between the Femur Neck Shaft and Anteversion Angles: A Retrospective Computed Tomography Analysis in Patients With Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:538-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kinsey TL, Anderson DN, Phillips VM, Mahoney OM. Disease Progression After Lateral and Medial Unicondylar Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3441-3447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tayyab M, Ahmad M, Shah RM, Shah S, Khan AA, Syed R, Shabir M, Khan A, Ali M, Syed F. Burden of Osteoarthritis in Pakistan and Its Provinces From 1990 to 2021: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study. Cureus. 2025;17:e90967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schmucker AM, Hupert N, Mandl LA. The Impact of Frailty on Short-Term Outcomes After Elective Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2019;10:2151459319835109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rao AR, Singh S, Gudeti B, Mehta PK, Malhotra R, Chakrawarty A, Dey AB, Chatterjee P. Frailty assessment as a predictor of postoperative complications and life space in Indian older adults undergoing elective major orthopaedic surgery: A prospective study from a tertiary care centre. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Plus. 2025;2:100198. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Pulik Ł, Jaśkiewicz K, Sarzyńska S, Małdyk P, Łęgosz P. Modified frailty index as a predictor of the long-term functional result in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty. Reumatologia. 2020;58:213-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manrique J, Komnos GA, Tan TL, Sedgh S, Shohat N, Parvizi J. Outcomes of Superficial and Deep Irrigation and Debridement in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1452-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang Y, Che K, Deng J, Tang X, Jing W, He X, Yang J, Zhang W, Yin M, Pan C, Huang X, Zhang Z, Ni J. Assessing the Impact of Frailty on Infection Risk in Older Adults: Prospective Observational Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024;10:e59762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pakistan Arthroplasty Society. About PNJR. Pakistan Arthroplasty Society Website. 2025. Available from: https://www.arthroplasty.org.pk/about-pnjr/. |

| 14. | Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, Peters D, Rubinfeld I. Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J Surg Res. 2013;183:104-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 660] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McMasters KM. Life, Surgery, and the Philosophy of Dry Creek. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Scuderi GR, Bourne RB, Noble PC, Benjamin JB, Lonner JH, Scott WN. The new Knee Society Knee Scoring System. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:3-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright RJ, Wright EA, Sledge CB; Kinemax Outcomes Group. Validity and responsiveness of the Knee Society Clinical Rating System in comparison with the SF-36 and WOMAC. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1856-1864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wall BJ, Wittauer M, Dillon K, Seymour H, Yates PJ, Jones CW. Clinical frailty scale predicts outcomes following total joint arthroplasty. Arthroplasty. 2025;7:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Afilalo J. Frailty in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: Why, When, and How to Measure. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2011;5:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Usmani BA, Lakhdir MPA, Sameen S, Batool S, Odland ML, Goodman-Palmer D, Agyapong-Badu S, Hirschhorn LR, Greig C, Davies J. Exploring the priorities of ageing populations in Pakistan, comparing views of older people in Karachi City and Thatta. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0304474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li Y, Du J, He L, Chen Y, Liu L, Yan H. A longitudinal study on the correlation between postoperative complications and frailty in older patients with joint disorders. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2025;37:214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jin Y, Tang S, Wang W, Zhang W, Hou Y, Jiao Y, Hou B, Ma Z. Preoperative frailty predicts postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty in older patients: a prospective observational study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2024;15:657-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khalid T, Ben-Shlomo Y, Bertram W, Culliford L, England C, Henderson E, Jameson C, Jepson M, Palmer S, Whitehouse MR, Wylde V. Prehabilitation for frail patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement: protocol for the Joint PREP feasibility randomised controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023;9:138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024. |

| 25. | Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Parametric mixture models to evaluate and summarize hazard ratios in the presence of competing risks with time-dependent hazards and delayed entry. Stat Med. 2011;30:654-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/