Published online Feb 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.114984

Revised: October 30, 2025

Accepted: December 8, 2025

Published online: February 18, 2026

Processing time: 123 Days and 19.8 Hours

Some scholars believe that there is a certain correlation between coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and the occurrence of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCF), but no relevant domestic research reports have been published yet. This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of pa

To explore risk factors for senile OVCF during COVID-19 normalization.

Retrospective analysis of 230 OVCF patients (June 2022 to June 2023, percutaneous vertebroplasty, observation group) and 236 controls (June 2020 to June 2021, OVCF surgery). Observation group was split into nucleic acid-positive (n = 85) and negative (n = 145) subgroups. Fracture location/cause, visual analogue scale, activity scores were compared; risk factors identified.

Observation group had 42.2% thoracic fractures and 38.2% cough-induced fractures (both higher than controls, P < 0.05). No significant differences in post-op visual analogue scale (1 day, 1 month) or activity scores (P > 0.05). Nucleic acid results, fracture cause/location correlated (P < 0.05; cause-location r = 0.827). Logistic regression showed fracture cause, nucleic acid result, body mass index, bone mineral density as high-risk factors.

During COVID-19 normalization, cough is the top OVCF cause; thoracic fractures rise. The four factors above are independent risks. For elderly COVID-positive patients with recurrent cough, lung disease treatment, anti-osteoporosis therapy, and thoracic braces prevent thoracic OVCF.

Core Tip: During the normalized prevention and control period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), compared with cases in the same period, cough is the main cause of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture (OVCF), and most fractures are thoracic fractures. After percutaneous vertebroplasty treatment, the improvement of pain and function in patients is not significantly different from that in the same period. Regression analysis shows that cause of fracture, nucleic acid test result, body mass index, and bone mineral density are independent risk factors for thoracic OVCF. For elderly COVID-19-positive patients with recurrent cough, timely and active treatment of lung diseases, aggressive anti-osteoporosis therapy, and wearing a thoracic brace for protection are effective measures to prevent thoracic OVCF.

- Citation: Li YF, Wu CQ, Long Y, Yu QF, Xu W, Zhao JJ, Zhang XY, Li ZK. Risk factors for thoracic-osteoporotic thoracic vertebral compression fractures during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19. World J Orthop 2026; 17(2): 114984

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i2/114984.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.114984

In December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) broke out globally, including in China. The World Health Organization officially classified the COVID-19 epidemic as a public health emergency of international concern in January 2020, which poses a severe threat to human life and health. Through the implementation of sustained and effective epidemic prevention policies, significant achievements have been made in domestic epidemic prevention and control. With the adjustment of COVID-19 management from “class B infectious diseases managed with class A measures” to “class B infectious diseases managed with class B measures”, China has entered a new phase of epidemic prevention and control, shifting the focus from “preventing infection” to “protecting health and preventing severe cases”. Meanwhile, the number of people infected with the virus has increased on a large scale across the country[1]. The COVID-19 epidemic in Shanghai began in late February 2022. According to public information, 1 local asymptomatic infected case was reported in Shanghai on February 24, marking the start of this round of epidemic. After more than two months of continuous efforts, Shanghai fully resumed normal production and living order on June 1, 2022, indicating that this round of epidemic was effectively controlled. Since then, Shanghai has entered the normalized phase of epidemic prevention and control[2].

An epidemiological study in China confirmed that among COVID-19 patients, those aged 30-80 years account for approximately 86.6%, of which 66.5% are over 50 years old. Most of these elderly patients are accompanied by postmenopausal osteoporosis or senile osteoporosis, and some even have concurrent osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCF)[3]. Clinical data show that most patients still have recurrent cough symptoms during the recovery period of COVID-19 infection, which can last for more than 4 weeks. In severe cases, this may lead to thoracolumbar fractures[4]. Some scholars believe that there is a certain correlation between COVID-19 infection and the occurrence of OVCF, but no relevant domestic research reports have been published yet[5,6]. This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients admitted for OVCF and treated with percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19 in Shanghai (after June 1, 2022), aiming to explore the individual differences of OVCF patients during this special period and analyze the risk factors for OVCF.

Patients who were admitted due to OVCF and underwent PVP from June 2022 to June 2023 were collected through the medical record query system as the observation group. Meanwhile, patients with the same diagnosis who were admitted and underwent surgery from June 2020 to June 2021 were collected as the control group. Inclusion criteria: (1) Confirmed diagnosis of OVCF with a single-segment fracture; (2) Meeting the diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis (T-score < -2.5) by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry bone mineral density (BMD) testing, or a Hounsfield unit value < 90 by computed tomography; and (3) Complete medical records. Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with multi-segment fractures; (2) Pa

General conditions of patients before surgery, including gender, age, body mass index (BMI), BMD, cause of onset, fracture location, and COVID-19 nucleic acid test result. Additionally, the visual analogue scale (VAS) score for pain and activity ability score were evaluated before surgery, at 1 day after surgery, and during the re-examination at 1 month after surgery. The Likert 4-point scale was used to assess activity ability, with higher scores indicating better activity ability: 1 point = able to get out of bed and move freely; 2 points = able to get out of bed and move with assistance; 3 points = unable to get out of bed and requiring a wheelchair; 4 points = bedridden and completely unable to get out of bed.

Descriptive analysis: Comparison of general information, fracture location, and cause of onset between the two groups.

Analysis of high-risk factors during the normalized COVID-19 prevention and control period: The observation group was divided into a positive subgroup (n = 85) and a negative subgroup (n = 145) based on COVID-19 nucleic acid test results. The causes of fractures between the two subgroups were compared, and binary logistic regression analysis was performed.

Comparison of surgical efficacy: Comparison between the two periods and between the COVID-19 nucleic acid-positive and negative subgroups.

SPSS 21.0 statistical software (IBM, United States) was used for data processing and analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the normal distribution of measurement data. Measurement data conforming to normal distribution and homogeneous variance were expressed as mean ± SD, and the independent samples t-test was used for comparison between the two groups; otherwise, the non-parametric test was used. Count data were expressed as the

Assignment of independent variables for regression analysis: Fracture segment: Thoracic segment = 1, thoracolumbar segment = 2, lumbar segment = 3; cause of fracture: Cough = 1, fall = 2, fall from height = 3, sprain = 4, lifting heavy objects = 5; nucleic acid test result: Positive = 1, negative = 2; BMI: Underweight (BMI < 18.5) = 1, normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24.0) = 2, overweight (24.0 ≤ BMI < 28.0) = 3, obesity (BMI ≥ 28.0) = 4; BMD: Osteoporosis ( ≤ -2.5) = 1, osteopenia

The observation group included 230 patients, with 56 males and 174 females; the average age was 75.96 ± 6.00 years; the average BMI was 21.80 ± 2.31 kg/m2; the average lumbar BMD was -2.31 ± 0.83 g/cm2. The control group included 236 patients, with 49 males and 187 females; the average age was 76.76 ± 5.44 years; the average BMI was 22.05 ± 2.41 kg/m2, the average lumbar BMD was -2.40 ± 0.67 g/cm2. There were no statistically significant differences in gender, age, BMI, or BMD between the two groups (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 1.

| Parameter | Observation group (n = 230) | Control group (n = 236) | χ2 | P value |

| Gender | 56 males, 174 females | 49 males, 187 females | -1.539 | 0.125 |

| Age (years) | 75.96 ± 6.00 | 76.76 ± 5.44 | -1.518 | 0.130 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.80 ± 2.31 | 22.05 ± 2.41 | -1.107 | 0.269 |

| BMD (g/cm2) | -2.31 ± 0.83 | -2.40 ± 0.67 | 1.280 | 0.201 |

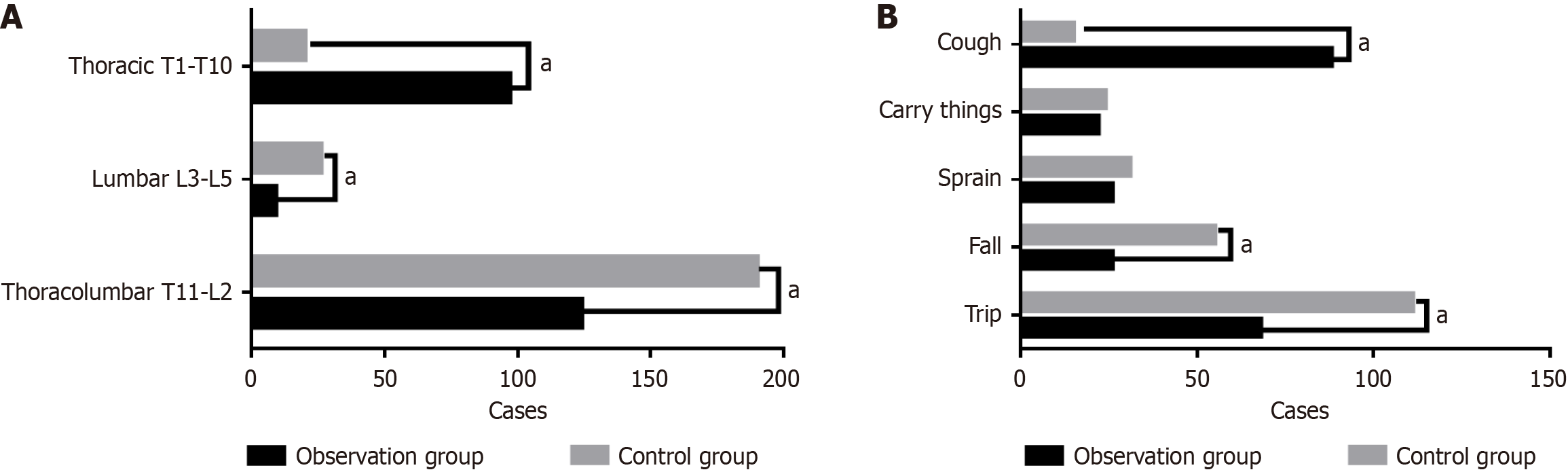

There were statistically significant differences in the cause and location of fractures between the observation group and the control group (P < 0.05). In the observation group, the number of fractures in the thoracolumbar segment, lumbar segment, and thoracic segment was 124 cases (53.9%), 9 cases (3.9%), and 97 cases (42.2%), respectively; in the control group, the number of fractures in the thoracolumbar segment, lumbar segment, and thoracic segment was 190 cases (80.5%), 26 cases (11.0%), and 20 cases (8.5%), respectively. The number of patients with thoracic fractures was significantly increased in the observation group (P < 0.001).

In the observation group, the number of fractures caused by falls at the same level, falls from height, sprains, lifting heavy objects, and coughs was 68 cases (29.6%), 26 cases (11.3%), 26 cases (11.3%), 22 cases (9.6%), and 88 cases (38.2%), respectively; in the control group, the number of fractures caused by the above factors was 111 cases (47.0%), 55 cases (23.3%), 31 cases (13.1%), 24 cases (10.2%), and 15 cases (6.4%), respectively. Cough was the main cause of fractures in the observation group, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). Details are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

| Item | Observation group (n = 230) | Control group (n = 236) | χ2 | P value |

| Fracture location | ||||

| Thoracolumbar segment (T11-L2) | 124 (53.9) | 190 (80.5) | 37.485 | < 0.01a |

| Lumbar segment (L3-L5) | 9 (3.9) | 26 (11.0) | 8.462 | 0.0036a |

| Thoracic segment (T1-T10) | 97 (42.2) | 20 (8.5) | 70.348 | < 0.01a |

| Cause of fracture | ||||

| Fall at the same level | 68 (29.6) | 111 (47.0) | 15.024 | 0.0001a |

| Fall from height | 26 (11.3) | 55 (23.3) | 11.681 | 0.0006a |

| Sprain | 26 (11.3) | 31 (13.1) | 0.363 | 0.546 |

| Lifting heavy objects | 22 (9.6) | 24 (10.2) | 0.0478 | 0.826 |

| Non-cough causes of fracture | 142 | 221 | ||

| Cough | 88 (38.2) | 15 (6.4) | 68.864 | < 0.01a |

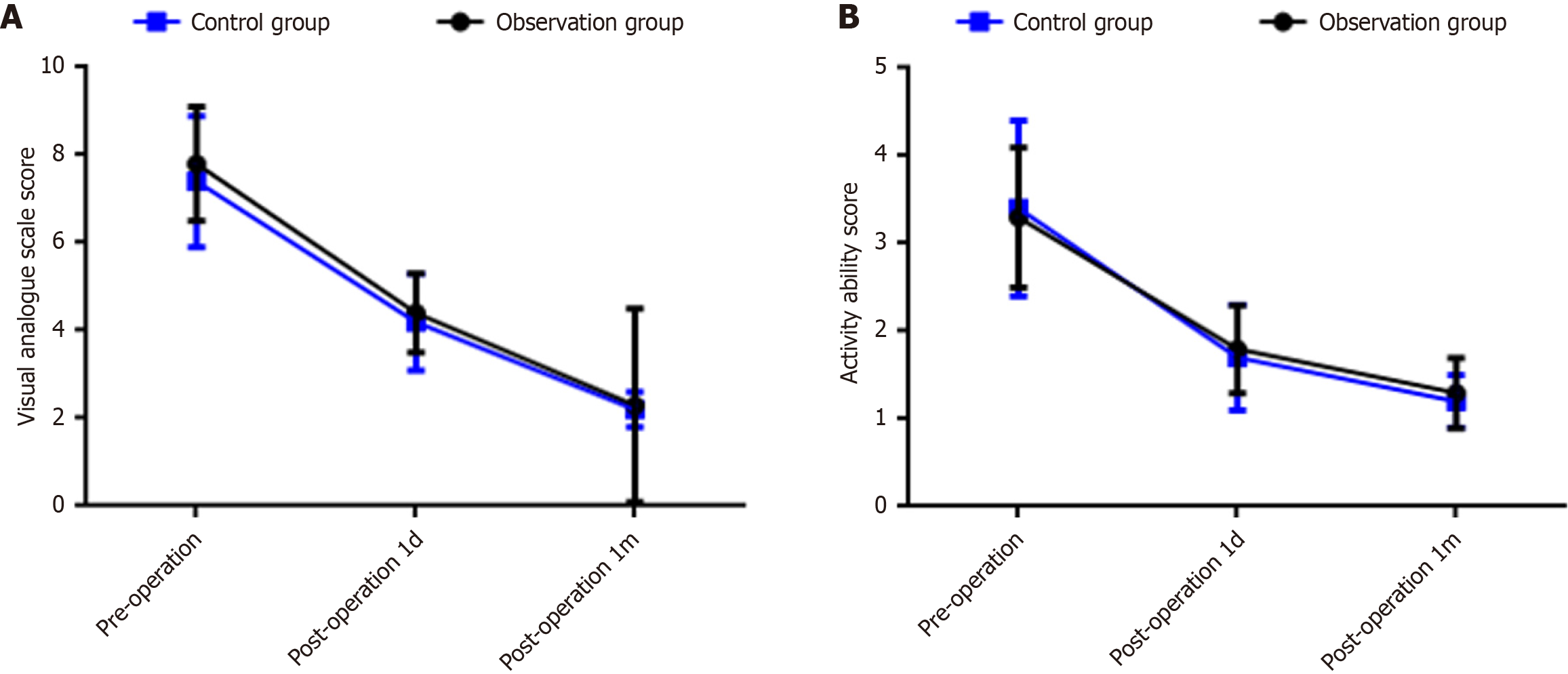

Before surgery, the VAS score of the observation group was significantly higher than that of the control group, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05); there were no statistically significant differences in VAS scores at 7 days and 1 month after surgery, or in activity ability scores before and after surgery between the two groups (P > 0.05). Details are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2.

| Item | Observation group (n = 230) | Control group (n = 236) | t | P value |

| VAS score (points) | ||||

| Pre-operation | 7.8 ± 1.3 | 7.4 ± 1.5 | 2.097 | 0.037 |

| 1 day post-operation | 4.4 ± 0.9a | 4.2 ± 1.1a | 1.457 | 0.146 |

| 1 month post-operation | 2.3 ± 0.5a | 2.2 ± 0.4a | 1.681 | 0.094 |

| Activity ability score (points) | ||||

| Pre-operation | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 0.807 | 0.420 |

| 1 day post-operation | 1.8 ± 0.5a | 1.7 ± 0.6a | 1.328 | 0.185 |

| 1 month post-operation | 1.3 ± 0.4a | 1.2 ± 0.3a | 1.942 | 0.053 |

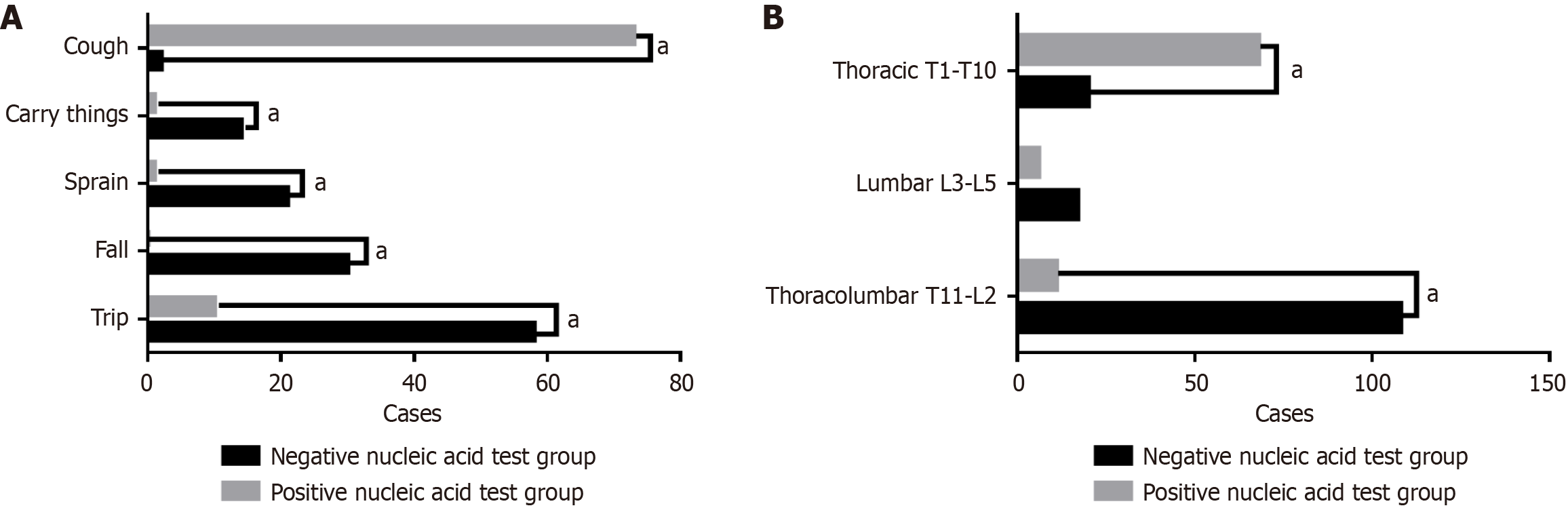

According to the COVID-19 nucleic acid test results, patients in the observation group were divided into the positive subgroup and the negative subgroup. There were significant differences in thoracolumbar fractures and thoracic fractures between the two subgroups with different nucleic acid test results (P < 0.01). All causes of fractures showed statistically significant differences between the two subgroups, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 3.

| Item | Negative subgroup (n = 145) | Positive subgroup (n = 85) | χ2 | P value |

| Fracture location | ||||

| Thoracolumbar segment (T11-L2) | 108 (74.5) | 11 (12.9) | 81.279 | < 0.001a |

| Lumbar segment (L3-L5) | 17 (11.7) | 6 (7.1) | 1.295 | 0.255 |

| Thoracic segment (T1-T10) | 20 (13.8) | 68 (80.0) | 99.437 | < 0.001a |

| Cause of fracture | ||||

| Fall at the same level | 58 (40.90) | 10 (28.24) | 20.515 | < 0.001a |

| Fall from height | 30 (22.76) | 0 (11.76) | 20.224 | < 0.001a |

| Sprain | 21 (14.48) | 1 (9.41) | 10.968 | 0.0009a |

| Lifting heavy objects | 14 (10.66) | 1 (9.41) | 6.149 | 0.0131a |

| Cough | 2 (6.21) | 73 (41.18) | 174.127 | < 0.001a |

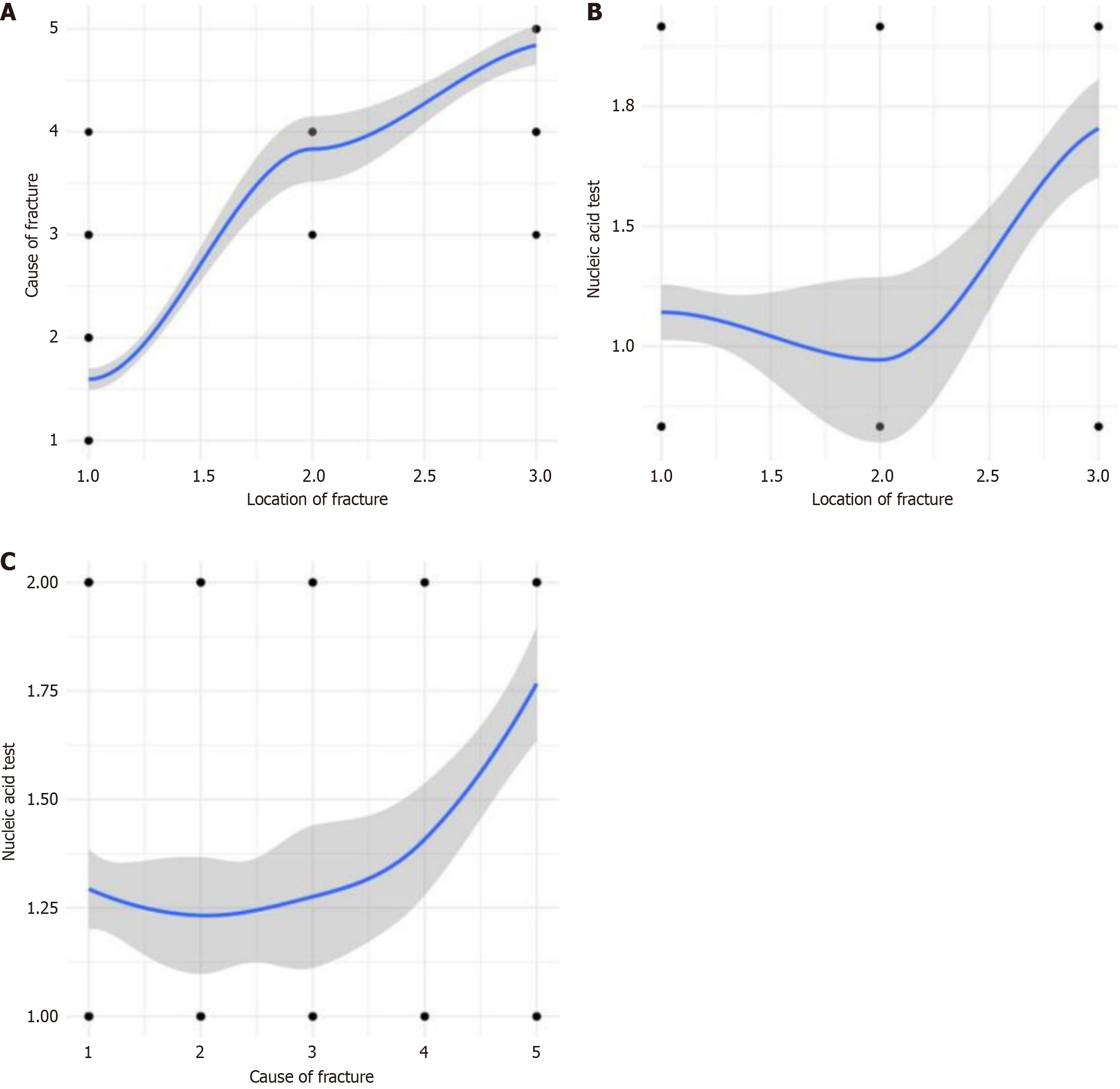

Correlation analysis between cause of fracture and fracture location: The correlation coefficient r = 0.827 (P < 0.01), indicating that the correlation coefficient between cause of fracture and fracture location is statistically significant, and there is a positive correlation between cause of fracture and fracture location (Figure 4A).

Correlation analysis between fracture location and nucleic acid test result: The correlation coefficient r = 0.332 (P < 0.01), indicating that the correlation coefficient between fracture location and nucleic acid test result is statistically significant, and there is a positive correlation between fracture location and nucleic acid test result (Figure 4B).

Correlation analysis between cause of fracture and nucleic acid test result: The correlation coefficient r = 0.287 (P < 0.01), indicating that the correlation coefficient between cause of fracture and nucleic acid test result is statistically significant, and there is a positive correlation between cause of fracture and nucleic acid test result (Figure 4C).

Comprehensive test of model coefficients: Significance < 0.01, indicating that the model is valid. Among the variables in the equation, cause of fracture [P < 0.01, odds ratio (OR) = 3.66], nucleic acid test result (P = 0.01, OR = 4.82), BMI (P < 0.01, OR = 4.69), and BMD (P < 0.03, OR = 3.52) were statistically significant, as shown in Table 5.

| Variable | B | SE | P value | Exponentiated B |

| Gender | 0.244 | 0.666 | 0.714 | 1.276 |

| Age | 0.410 | 0.383 | 0.284 | 1.507 |

| Cause of fracture | 1.298 | 0.197 | 0.000 | 3.660 |

| Nucleic acid test result | 1.573 | 0.613 | 0.010 | 4.821 |

| BMI | 1.546 | 0.406 | 0.000 | 4.691 |

| BMD | 1.259 | 0.424 | 0.003 | 3.521 |

| Constant | -13.451 | 2.461 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

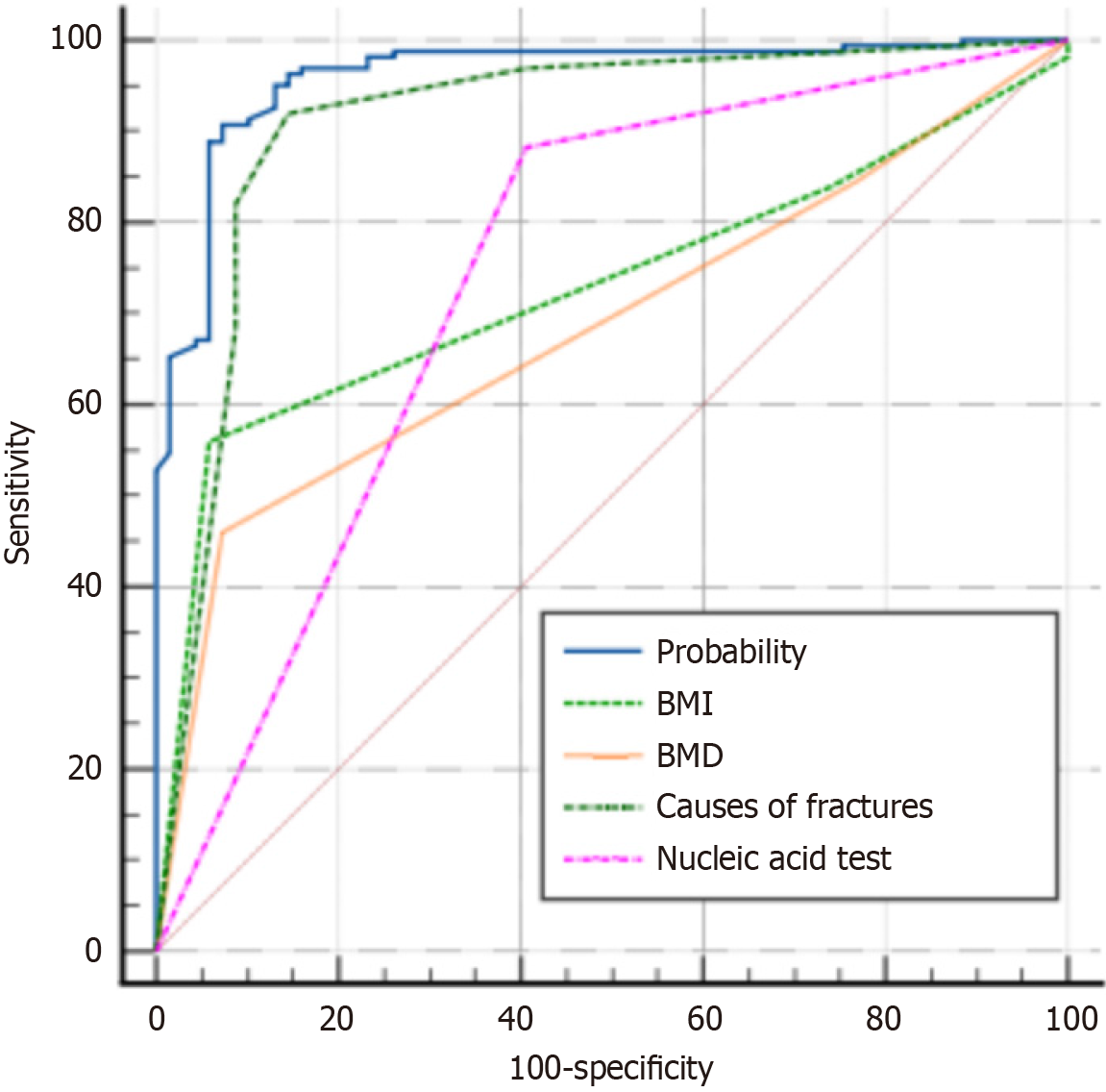

Regression equation: logit (p) = (-13.451) + 1.298 × cause of fracture + 1.573 × nucleic acid test result + 1.546 × BMI + 1.259 × BMD. The probability area under the curve value of the regression equation was 0.961, and other area under the curve values are shown in Table 6 and Figure 5.

| Variable | AUC | SE | 95%CI |

| Probability | 0.961 | 0.0130 | 0.927-0.982 |

| BMI | 0.730 | 0.0304 | 0.667-0.786 |

| BMD | 0.684 | 0.0314 | 0.620-0.744 |

| Cause of fracture | 0.911 | 0.0237 | 0.867-0.945 |

| Nucleic acid test result | 0.738 | 0.0324 | 0.676-0.794 |

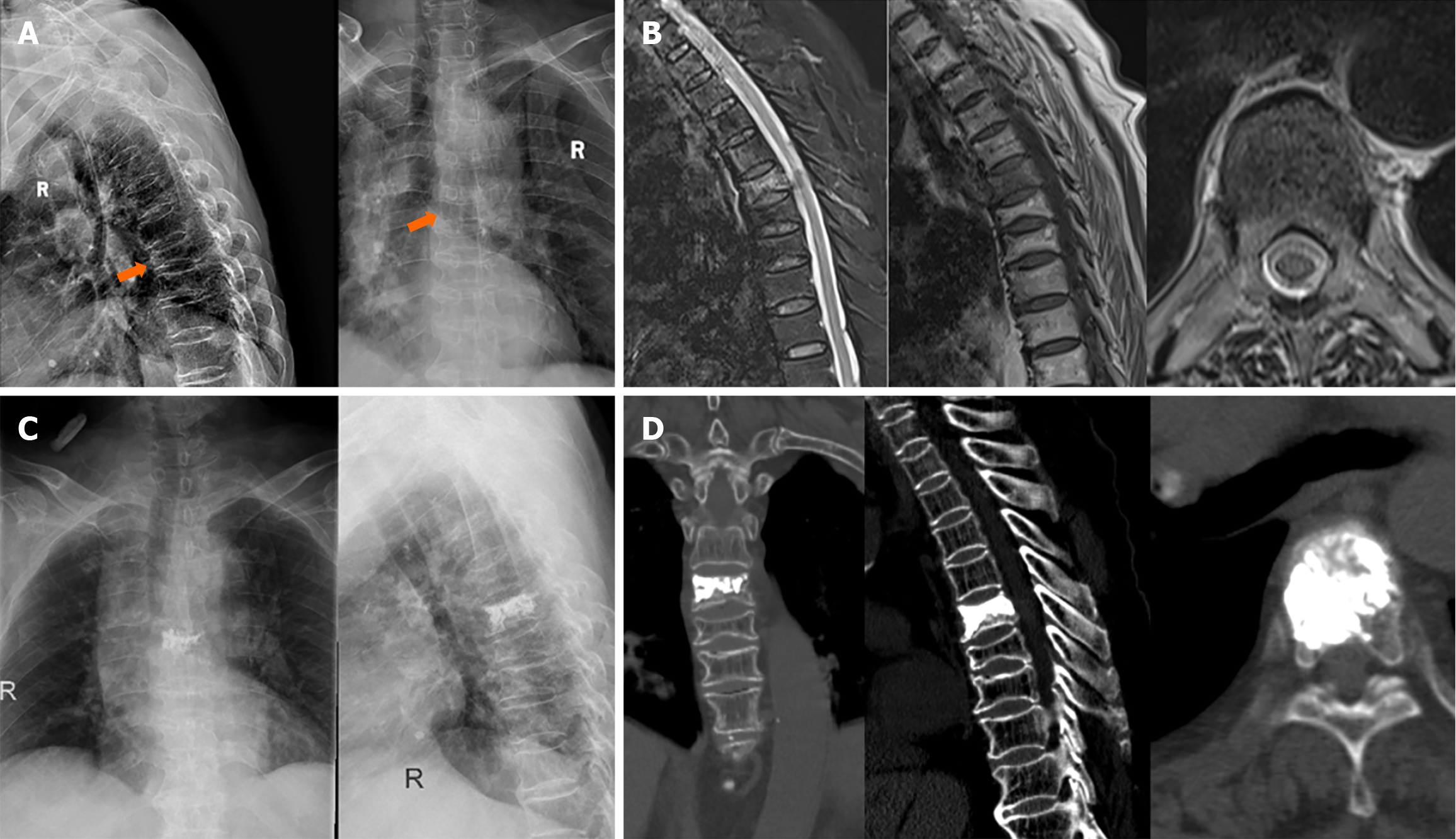

A case, female, 87 years old, tested positive for COVID-19, was admitted to the hospital due to back pain after recurrent cough for 1 month. She was diagnosed with T6 osteoporotic fracture and underwent PVP treatment. The pain symptoms were improved after surgery, as shown in Figure 6.

Currently, there are still few studies on vertebral fractures after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Some studies have reported that vertebral fractures are relatively common in COVID-19 patients, with 36% of patients showing vertebral deformities, but only 3% of patients have a previous diagnosis of osteoporosis. A study by Yu et al[7] suggested that COVID-19 patients have varying degrees of hypercoagulable state, leukocyte aggregation, and vascular inflammation, all of which may damage the blood flow of bone microvessels, thereby promoting the occurrence and development of osteonecrosis. At the same time, cytokines induced by COVID-19, such as interleukin-17, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10, can reduce osteoblast proliferation and induce osteoclast formation, leading to a net decrease in BMD. In a study by Qiao et al[8], hamsters infected with COVID-19 experienced severe bone loss, which could persist until the recovery period. Additionally, the number of osteoclast precursor cells increased, and the type I interleukin-1β receptor was significantly upregulated in CD68-positive cells expressing tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase. This confirms that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection activates the osteoclast cascade, thereby causing damage to the trabecular structure in long bones and axial bones. Therefore, there is a close relationship between COVID-19 infection and bone loss. A study by Patil et al[9] pointed out that the risk of vertebral fractures increases after COVID-19, and chest computed tomography shows that thoracolumbar fractures account for approximately two-thirds of all vertebral fractures. Another study suggested that recurrent cough can lead to osteoporotic thoracic fractures, and many OVCF patients were ignored and missed diagnosis during the epidemic, failing to receive scientific treatment[5,6]. On the other hand, this study shows that OVCF patients during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19 have higher VAS scores than those in the same period. Therefore, OVCF during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19 require attention.

Previous studies have shown that OVCF are most common in the thoracolumbar segment, and the common causes include falls, drops, and lifting heavy objects[10,11]. However, the characteristics of OVCF during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19 are different. During this period, OVCF are most common in the middle thoracic spine, and cough is the main cause of fractures, both of which are significantly higher than those in the same period. World Health Organization led a collaboration of global medical scientists to complete the largest-scale study on long COVID to date. By following up self-reported data from 1.2 million confirmed COVID-19 patients in 22 countries and combining global COVID-19 infection data analysis, it was found that persistent respiratory problems are a group of long-term symptoms after COVID-19 infection[12]. Results from a large-scale domestic study showed that cough is the second most common symptom in COVID-19 patients during hospitalization, after fever, accounting for approximately 67.8%[13]. A study by Davis et al[14] found that the incidence of respiratory diseases in COVID-19 patients is twice that of the general population, and shortness of breath and cough are the most common respiratory symptoms, with 40% and 20% of long COVID patients experiencing these symptoms for at least 7 months, respectively. During this period, the COVID-19 virus spread, and patients developed cough after infection. Elderly patients had a long treatment cycle for COVID-19, and recurrent cough led to middle thoracic fractures[15]. Therefore, middle thoracic fracture location and cough as the cause of onset are the characteristics of senile osteoporotic thoracic vertebral compression fractures during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19 in Shanghai. On the other hand, elderly people have vertebral deformation and ligament relaxation due to osteoporosis, and further bone loss after COVID-19 infection leads to varying degrees of thoracic kyphosis. Coughing exacerbates this kyphosis, resulting in high stress at the middle thoracic spine, which in turn causes thoracic compression fractures[16,17].

In recent years, with the acceleration of the aging process, the incidence of osteoporosis has been increasing year by year. OVCF is a common complication of osteoporosis, mainly manifested as sudden severe pain and progressive kyphosis, which seriously affects the quality of life of elderly patients and significantly increases the mortality rate[18]. PVP is currently the most commonly used method for treating OVCF, which can effectively relieve clinical symptoms and improve the quality of life. Statistical data show that there are up to 44.49 million OVCF patients in China, with more than 1.8 million new cases each year[19]. These patients are often complicated with various underlying diseases, organ dysfunction, and decreased body compensatory capacity[20]. During the COVID-19 epidemic, due to reduced mobility, decreased physical activity, and the combined effects of environment and stress, the skeletal muscle mass of the elderly population decreased, resulting in lumbodorsal muscle soreness. Moreover, recurrent cough after COVID-19 infection aggravated lumbodorsal pain[21].

The study results show that the VAS score for pain in OVCF patients during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19 in Shanghai is higher than that in the same period, which may be related to the cause and location of fractures in the two groups. Thoracic fractures caused by cough have higher VAS scores. However, there is no significant difference in VAS scores between the two periods after vertebroplasty. Therefore, vertebroplasty has a good therapeutic effect on thoracic OVCF caused by cough, and the therapeutic effect remains stable during the follow-up at 1 month after surgery.

Patients during this special period were grouped according to nucleic acid test results. The results showed that 80% of nucleic acid-positive patients had thoracic fractures, and 73% of them had cough as the cause of fracture. During the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19, patients infected with the COVID-19 virus had positive nucleic acid test results, cough was the main clinical manifestation, and recurrent cough-induced thoracic stress fractures were the pathogenesis of fractures. Correlation analysis showed that there were positive correlations between nucleic acid test results, fracture location, and cause of onset. Among them, the correlation between cause of fracture and fracture location was the strongest (correlation coefficient r = 0.827, P < 0.01). The correlations between cause of fracture (r = 0.287) and fracture location (r = 0.332) with nucleic acid test results were weak. Therefore, for elderly patients with positive nucleic acid test results, it is necessary to attach great importance to the screening of OVCF, especially in the case of recurrent cough, and check whether there is percussion pain in the back.

Logistic regression analysis revealed that fracture cause (P < 0.01, OR = 3.66), nucleic acid (P = 0.01, OR = 4.82), BMI (P < 0.01, OR = 4.69), and bone density (P < 0.03, OR = 3.52) were high-risk factors for thoracic OVCF. Among them, the odds ratio of nucleic acid was the highest. The probability area under the curve value of the regression equation was 0.961, indicating a good predictive effect. When coughing was the cause of fracture, nucleic acid was positive, BMI was less than 18.5, and bone density was less than or equal to -2.5, the incidence of thoracic fractures was as high as 96.1%. Additionally, it is worth noting that BMI and bone density are also high-risk factors for thoracic OVCF. These are patient’s own factors that cannot be controlled in the short term, while the cause of fracture and nucleic acid results can be prevented in the short term.

To further identify the risk factors for thoracic OVCF during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19, binary logistic regression analysis showed that cause of fracture, nucleic acid test result, BMI, and BMD were risk factors for thoracic OVCF during this period. The OR from high to low were: Nucleic acid test result (OR = 4.82), BMI (OR = 4.69), cause of fracture (OR = 3.66), and BMD (OR = 3.52). The prediction accuracy of the regression equation was 0.961. Therefore, during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19, it is important to perform thoracic MRI examinations on elderly patients with cough, positive nucleic acid test results, and back pain to prevent missed diagnosis of thoracic OVCF.

In view of the adjustment of epidemic prevention policies, COVID-19 has been classified as a class B infectious disease managed with class B measures. After the full liberalization, medical institutions have received a large number of post-infection patients, among whom there are many patients with chronic cough as the main symptom. When these patients experience persistent and severe thoracolumbar pain during the course of the disease, it is necessary to be alert to the occurrence of OVCF. First, active treatment of COVID-19 and the use of antitussive drugs to relieve cough symptoms are essential. Thoracic brace fixation can well protect against thoracic stress fractures caused by cough. Anti-osteoporosis drugs such as teriparatide and denosumab can reduce the incidence of thoracic OVCF, and special attention should be paid to patients with low BMI. Therefore, during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19, reasonable and standardized diagnosis and treatment, as well as timely and effective intervention, are of great significance for protecting the rapid recovery of patients with thoracic OVCF.

This study retrospectively analyzed clinical cases, first proposed the relationship between COVID-19 infection and the causes and locations of thoracic OVCF, summarized the characteristics of thoracic OVCF during the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19, and proposed effective prevention methods, which have high clinical guiding value. At the same time, there are some limitations. First, this study is a retrospective study, so bias may be introduced in data collection. Second, due to time constraints, no multi-center study was conducted, and the sample size was small, so the conclusions may not be comprehensive. A large-scale multi-center systematic analysis is still needed for the characteristics of OVCF patients during the COVID-19 epidemic.

During the normalized prevention and control period of COVID-19, compared with cases in the same period, cough is the main cause of OVCF, and most fractures are thoracic fractures. After PVP treatment, the improvement of pain and function in patients is not significantly different from that in the same period. Regression analysis shows that cause of fracture, nucleic acid test result, BMI, and BMD are independent risk factors for thoracic OVCF. For elderly COVID-19-positive patients with recurrent cough, timely and active treatment of lung diseases, aggressive anti-osteoporosis therapy, and wearing a thoracic brace for protection are effective measures to prevent thoracic OVCF.

| 1. | Drake TM, Riad AM, Fairfield CJ, Egan C, Knight SR, Pius R, Hardwick HE, Norman L, Shaw CA, McLean KA, Thompson AAR, Ho A, Swann OV, Sullivan M, Soares F, Holden KA, Merson L, Plotkin D, Sigfrid L, de Silva TI, Girvan M, Jackson C, Russell CD, Dunning J, Solomon T, Carson G, Olliaro P, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Turtle L, Docherty AB, Openshaw PJ, Baillie JK, Harrison EM, Semple MG; ISARIC4C investigators. Characterisation of in-hospital complications associated with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK: a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:223-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | The Lancet. China's response to COVID-19: a chance for collaboration. Lancet. 2021;397:1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Song DW, Niu JJ, Meng B, Liu T, Huang LX, Zou J, Yang HL. [Diagnosis and treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture during epidemic prevention and control of coronavirus disease 2019]. Zhonghua Gu Yu Guanjie Waike Zazhi. 2020;13:183-189. |

| 4. | Burki T. China's successful control of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1240-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | di Filippo L, Formenti AM, Doga M, Pedone E, Rovere-Querini P, Giustina A. Radiological Thoracic Vertebral Fractures are Highly Prevalent in COVID-19 and Predict Disease Outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e602-e614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Creecy A, Awosanya OD, Harris A, Qiao X, Ozanne M, Toepp AJ, Kacena MA, McCune T. COVID-19 and Bone Loss: A Review of Risk Factors, Mechanisms, and Future Directions. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2024;22:122-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Yu EW, Tsourdi E, Clarke BL, Bauer DC, Drake MT. Osteoporosis Management in the Era of COVID-19. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35:1009-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Qiao W, Lau HE, Xie H, Poon VK, Chan CC, Chu H, Yuan S, Yuen TT, Chik KK, Tsang JO, Chan CC, Cai JP, Luo C, Yuen KY, Cheung KM, Chan JF, Yeung KW. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces inflammatory bone loss in golden Syrian hamsters. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Patil V, Reddy AD, Kale A, Vadlamudi A, Kishore JVS, Jani C. Incidental Identification of Vertebral Fragility Fractures by Chest CT in COVID-19-Infected Individuals. Cureus. 2022;14:e24867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ma CH, Yang HL, Huang YT, Wu ZX, Cheng HC, Chou WC, Hung CH, Tsai KL. Effects of percutaneous vertebroplasty on respiratory parameters in patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Ann Med. 2022;54:1320-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xu W, Wang S, Chen C, Li Y, Ji Y, Zhu X, Li Z. Correlation analysis between the magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures and the efficacy of percutaneous vertebroplasty: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ashraf N, Abou Shaar B, Taha RM, Arabi TZ, Sabbah BN, Alkodaymi MS, Omrani OA, Makhzoum T, Almahfoudh NE, Al-Hammad QA, Hejazi W, Obeidat Y, Osman N, Al-Kattan KM, Berbari EF, Tleyjeh IM. A systematic review of trials currently investigating therapeutic modalities for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and registered on WHO International Clinical Trials Platform. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023;29:570-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fuggle NR, Singer A, Gill C, Patel A, Medeiros A, Mlotek AS, Pierroz DD, Halbout P, Harvey NC, Reginster JY, Cooper C, Greenspan SL. How has COVID-19 affected the treatment of osteoporosis? An IOF-NOF-ESCEO global survey. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32:611-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:133-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1688] [Cited by in RCA: 2556] [Article Influence: 852.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yu SH, Dong RC, Liu Z, Liu H, Liu YT, Tang SJ. Impact of Sacroiliac Interosseous Ligament Tension and Laxity on the Biomechanics of the Lumbar Spine: A Finite Element Study. World Neurosurg. 2024;185:e431-e441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luo AJ, Liao JC, Chen LH, Lai PL. High viscosity bone cement vertebroplasty versus low viscosity bone cement vertebroplasty in the treatment of mid-high thoracic vertebral compression fractures. Spine J. 2022;22:524-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu SC, Luo AJ, Liao JC. Cement augmentation for treatment of high to mid-thoracic osteoporotic compression fractures, high-viscosity cement percutaneous vertebroplasty versus balloon kyphoplasty. Sci Rep. 2022;12:19404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Maupin JJ, Steinmetz RG, Hickerson LE. A Percutaneous Threaded Wire as a Clamp Technique for Avoiding Wedge Deformity While Nailing Intertrochanteric Femur Fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33:e276-e279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yamauchi K, Adachi A, Kameyama M, Murakami M, Sato Y, Kato C, Kato T. A risk factor associated with subsequent new vertebral compression fracture after conservative therapy for patients with vertebral compression fracture: a retrospective observational study. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 20. | Jian Y, Zhu D, Zhou D, Li N, Du H, Dong X, Fu X, Tao D, Han B. ARIMA model for predicting chronic kidney disease and estimating its economic burden in China. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:2456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kirwan R, McCullough D, Butler T, Perez de Heredia F, Davies IG, Stewart C. Sarcopenia during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions: long-term health effects of short-term muscle loss. Geroscience. 2020;42:1547-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/