Published online Jan 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.114482

Revised: October 21, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: January 18, 2026

Processing time: 111 Days and 6.6 Hours

Aseptic loosening remains the leading cause of revision in primary total hip arthroplasty (pTHA). However, the literature demonstrates significant variability regarding the relative contributions of different factors.

To investigate the key determinants of aseptic loosening, we performed a sys

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library was conducted, encompassing studies from database inception to January 1, 2025. Meta-analyses were performed to evaluate factors associated with aseptic loosening following pTHA. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were systematically applied at each stage to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility. Study quality was assessed using standardized categories. Pooled odds ratio (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval were calculated with random- or fixed-effects models to generate reliability estimates, and study heterogeneity was visualized using forest plots. Ten factors, categorized into patient-, surgeon-, and device-related domains, were reviewed and meta-analyzed. Funnel plot analysis demonstrated a relatively symmetrical distribution, suggesting minimal publica

A meta-analysis of 20 studies (520789 participants) found a pooled prevalence of 1.96%. Significant risk factors for aseptic loosening after pTHA included elevated body mass index (OR = 1.116, P < 0.001), higher Charlson comorbidity index (OR = 1.378, P < 0.001), prosthesis-related factors (OR = 1.497, P < 0.001), and adverse lifestyles (OR = 2.198, P = 0.037). Protective factors were non-white race (OR = 0.445, P < 0.001) and favorable genetics (OR = 0.723, P < 0.001). Male sex increased risk (OR = 1.232, P = 0.016), while age and anatomy were not significant. Surgical expertise showed a slight protective effect (OR = 1.048, P < 0.001). A comprehensive under

The identification of these factors is critical for risk mitigation. High-risk patients should receive targeted coun

Core Tip: Aseptic loosening is the main cause of failure in primary total hip arthroplasty, yet the key risk factors remain unclear. Our meta-analysis of 20 studies clarifies this: Modifiable factors like high body mass index, comorbidity burden, and prosthesis choice significantly increase risk, while surgical expertise is protective. This evidence enables surgeons to identify high-risk patients and prioritize modifiable factors, paving the way for personalized prevention strategies and improved implant longevity.

- Citation: Li GQ, Zhang J, Huang Y. Factors associated with aseptic loosening after primary total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Orthop 2026; 17(1): 114482

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i1/114482.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.114482

Primary total hip arthroplasty (pTHA) remains the gold-standard surgical treatment for end-stage hip pathologies, demonstrating consistent efficacy in pain alleviation, functional recovery, and quality-of-life improvement[1]. Despite its clinical success, the increasing volume of pTHA procedures has revealed significant complications that impose considerable healthcare burdens through elevated costs and extended hospitalizations[2,3]. Among these complications, aseptic loosening emerges as the leading cause of late-term implant failure[4,5], though its multifactorial etiology and underlying biological mechanisms require further elucidation. The current evidence base demonstrates substantial heterogeneity in reported risk factors[6,7], underscoring the imperative for systematic evaluation. This knowledge gap necessitates a comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence to inform clinical decision-making and guide future research directions. Through systematic review and meta-analysis, we seek to quantify the factors that associated with aseptic loosening after pTHA.

The protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number CRD42023447688). This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in strict accordance with both the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 6.3) reported by Page et al[8].

A systematic literature search was performed to identify studies examining factors for aseptic loosening following pTHA. Four databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library) were searched from inception through January 1, 2025. The search strategy incorporated the following key concepts using Boolean operators: Risk factors: ("Risk Factor" OR "Health Correlates" OR "Population at Risk" OR "Risk Score"); implant failure: ("Prosthesis Failure" OR "Aseptic Loosening" OR "Prosthesis Survival" OR "Prosthesis Migration"); surgical procedure: ("Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip" OR "Total Hip Arthroplasty" OR "Hip Prosthesis Implantation"). Potentially eligible articles were screened based on title or abstract, followed by full-text review. Reference lists of included studies were manually searched to identify additional relevant publications. The complete search syntax is detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

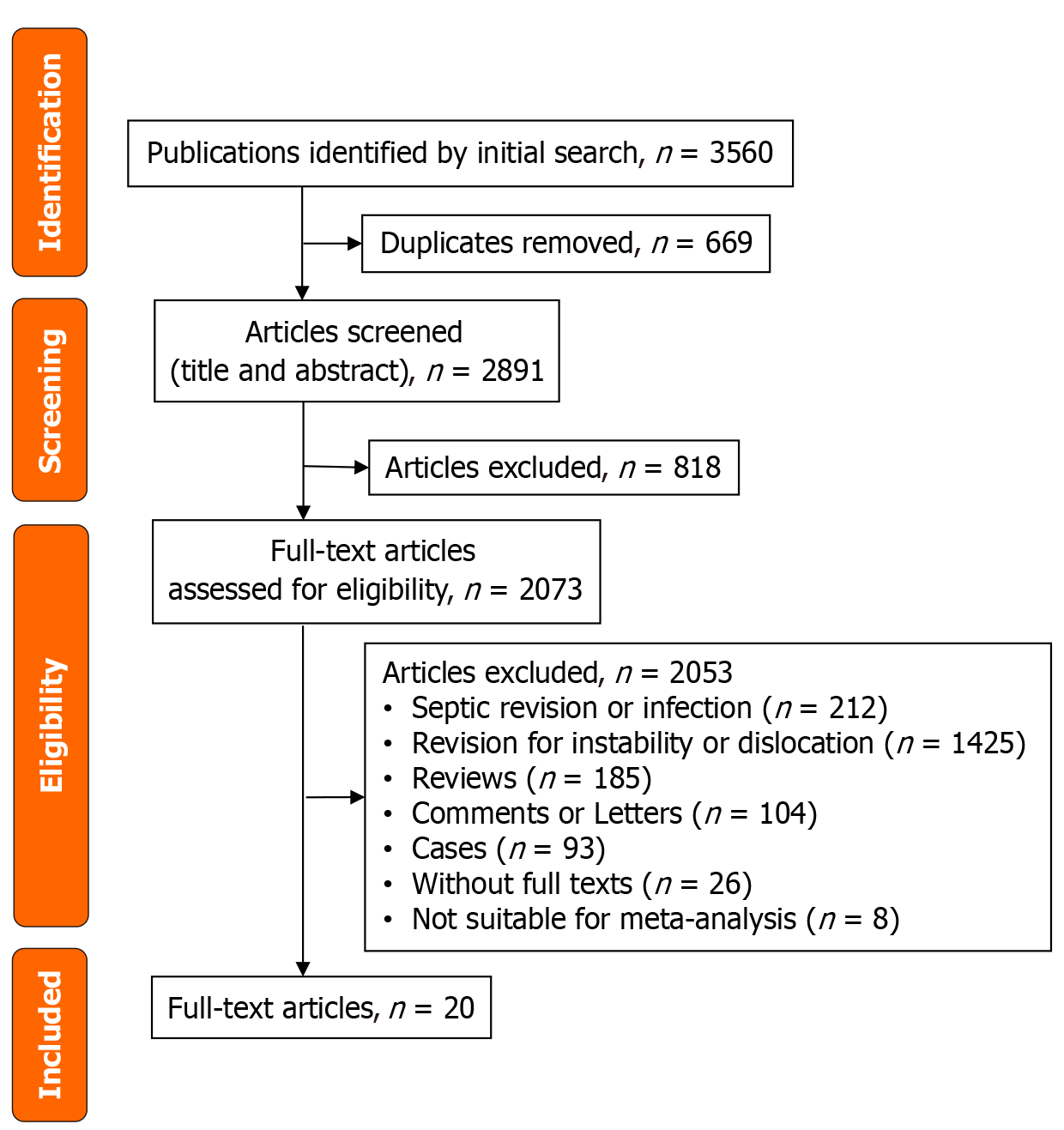

Studies were included if they met the following criterias: (1) Investigations examining factors for aseptic loosening following pTHA; (2) Sample size over 30 participants; (3) Minimum follow-up duration of 1 year; and (4) Reported odds ratio (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI). Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) Studies involving septic revisions, periprosthetic infections, or revisions for instability or dislocation; (2) Non-original research publications (reviews, commentaries, letters, or case reports); (3) Unavailable full-text articles; and (4) Studies with insufficient data for meta-analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process, demonstrating the systematic application of these criteria to ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility.

The study selection process was conducted through independent screening and data extraction by two researchers (Li GQ and Huang Y). All identified records were imported into EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics) for duplicate removal. The researchers independently evaluated titles and abstracts for eligibility, with any discrepancies resolved through consensus discussion or arbitration by a third investigator (Zhang J). Using a standardized extraction form, the same researchers collected the following data: Study characteristics: First author, publication year, country, and study design; population details: Sample size, mean age, and follow-up duration; outcome measures: Aseptic loosening rates; statistical analyses: Methods employed and significant risk factors for aseptic loosening. All extracted data were cross-verified, with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer (Zhang J).

The methodological quality of included cohort studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which assesses three domains: (1) Selection; (2) Comparability; and (3) Outcome evaluation, through eight specific criteria. Cross-sectional studies were appraised using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) checklist, consisting of eleven items rated as "yes", "no", or "unclear". Two independent reviewers (Li GQ and Huang Y) conducted the quality assessments, with any discrepancies resolved through consultation with a third author (Zhang J).

All outcome metrics and raw data were tabulated in Microsoft Excel (version 16.16.2). Data management, effect size transformation, and calculation of pooled mean effect sizes were performed using comprehensive meta-analysis software (version 3.3.070). OR were pooled and forest plots were generated. The meta-analyses employed the inverse variance method. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with thresholds defined as follows: < 40% (low), 40%-60% (moderate), and > 60% (high). Pooled effect sizes with corresponding 95%CI were calculated. Heterogeneity was further evaluated using the Cochrane Q-statistic and I² statistic. A fixed-effect model was applied when I2 ≤ 50% and P > 0.1; otherwise, a random-effects model was used to provide more conservative estimates. In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by sequentially removing individual studies and reperforming the meta-analysis to observe changes in the pooled effect size and heterogeneity. When data extraction or standardized effect size calculation was not feasible, eligible studies were described narratively.

A systematic literature search across multiple databases initially identified 2891 potentially eligible studies. In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a rigorous multi-stage screening process. During initial screening, we excluded 212 studies focusing on septic revision or periprosthetic joint infection, as these topics were not relevant to our research objectives. Subsequent screening eliminated 1425 studies examining revision procedures for instability or dislocation, which fell outside our study scope. We further excluded 185 review articles (lacking original data), 104 commentaries or editorials (without substantive research content), and 93 case reports (due to small sample sizes and potential bias). Twenty-six studies were excluded because full-text versions were unavailable for thorough assessment. In addition, we excluded 8 studies that were methodologically unsuitable for meta-analysis due to insufficient outcome reporting or study design limitations. Finally, of total 20 studies were included.

The reviewed studies exhibited the following key characteristics: Authorship, country of origin, study design, follow-up duration, sample size, number of aseptic loosening cases and rates, age, and NOS scores (Table 1). These studies featured substantial sample sizes (range: 39-290770; total n = 520789) and extended follow-up periods (range: ≤ 2 years to ≥ 16 years). Conducted between 2005 and 2024 across eleven countries (United Kingdom, United States, Denmark, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Finland, Sweden, China, Ireland, and France), the majority employed cohort designs (n = 17), with three utilizing case-control methodologies. Participants' mean age predominantly ranged from 60 years to 70 years, with one exception reporting 46.5 years. Aseptic loosening cases varied substantially (4-1260 cases), with rates demonstrating considerable heterogeneity (0.2%-6.57%) with the pooled rate was 1.96%. All studies demonstrated good methodological quality, as evidenced by NOS scores of 6-8. Table 1 comprehensively summarizes these study characteristics, illustrating their diversity in design, population parameters, and outcome measures.

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Follow-up (years) | Participations | AL | AL rates, % | Age (years) | NOS |

| Davis et al[61], 2020 | United Kingdom | Cohort study | ≥ 7.5 | 290770 | 1260 | 0.43 | 73.17 | 7 |

| Amstutz et al[49], 2015 | United States | Case-control study | 8.58 | 1375 | 27 | 1.96 | 46.5 | 7 |

| Benson et al[35], 2022 | Denmark | Cohort study | 4.4 (1.1-5.9) | 53605 | 479 | 0.89 | NA | 7 |

| Bordini et al[15], 2007 | Italy | Cohort study | ≥ 6 | 4750 | 134 | 2.82 | NA | 6 |

| Jud et al[42], 2024 | Switzerland | Cohort study | NA | 2459 | 14 | 0.56 | 63.8 ± 12.7 | 7 |

| Wagener et al[62], 2024 | Germany | Cohort study | 2-10 | 255 | 255 | NA | 73 | 7 |

| Budin et al[34], 2024 | United States | Cohort study | 2 | 32811 | 721 | 2.19 | 69.1 ± 8.3 | 8 |

| Magruder et al[32], 2024 | United States | Cohort study | ≤ 2 | 11025 | 160 | 1.45 | NA | 6 |

| Aro et al[13], 2012 | Finland | Cohort study | 2 | 39 | NA | NA | 61.5 (41-78) | 6 |

| Electricwala et al[23], 2016 | United States | Cohort study | 8.7 ± 8.1 | 257 | NA | NA | 67 ± 13 | 7 |

| Münger et al[14], 2006 | Sweden | Case-control study | 5.3 ± 3.1 | 50534 | 725 | 1.43 | 63 ± 9.5 | 8 |

| Layson et al[29], 2024 | United States | Cohort study | 2 | 55601 | NA | 1.91 | 68-72 | 7 |

| Clauss et al[58], 2013 | Switzerland | Cohort study | ≥ 16 | 156 | 139 | NA | NA | 7 |

| Khatod et al[43], 2014 | United States | Cohort study | 2.2 (1.2-5.1) | 36834 | 635 | 1.72 | 65.5 ± 11.7 | 8 |

| Stelmach et al[45], 2015 | Germany | Cohort study | NA | 465 | 234 | NA | 52.80 ± 12.8 | 7 |

| Wedemeyer et al[44], 2009 | Germany | Cohort study | 7.17-8.41 | 87 | 87 | NA | 69.31 ± 10.27 | 7 |

| Lee et al[56], 2024 | China | Cohort study | ≥ 1 | 1995 | 4 | 0.2 | 61.9 ± 13.8 | 7 |

| Lunn et al[33], 2005 | Ireland | Case-control study | 5.7 (2-11) | 217 | 101 | NA | 67.6 ± 9.6 | 6 |

| Halawi et al[26], 2016 | United States | Cohort study | 7.6 ± 2.56 | 426 | 28 | 6.57 | 46.9 ± 7.1 | 7 |

| Boyer et al[19], 2019 | France | Cohort study | 5.5 | 30733 | NA | NA | NA | 6 |

The analyzed factors were categorized into three groups: Patient-related factors, surgical-related factors, and implant-related factors (Table 2). Patient-related factors commonly examined across studies included age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle factors encompassed tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and physical activity levels. Comorbidity factors consisted of the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease. Additionally, genetic factors and biomarkers, including polymorphisms, were analyzed. Surgical factors included surgical approach, procedure duration, and surgeon experience. Implant-related factors comprised implant type, fixation method, and component size. Table 2 also summarizes the statistical methods employed in each included study.

| Ref. | Statistics | Factors |

| Davis et al[61], 2020 | KM survival analysis and Cox regression analyses | Age, sex, head composition, and stem fixation method |

| Amstutz et al[49], 2015 | Multivariate analysis and Cox proportional hazard ratio | Age, gender, BMI, abduction arc, UCLA activity score, center-edge angle, cup abduction, component size, and diagnosis |

| Benson et al[35], 2022 | KM survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression model | Age, sex, CCI, fixation type, duration and start of thromboprophylaxis, use of vitamin K antagonists, NOAC, aspirin, and platelet inhibitors |

| Bordini et al[15], 2007 | Multivariate survival analysis and Cox proportional -hazards model | Age, gender, diagnosis, Charnley score, right or left side, surgeon’s skill, and type of components |

| Jud et al[42], 2024 | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | Age, non-steroidal antirheumatics, and nicotine |

| Wagener et al[62], 2024 | KM method and Cox proportional hazards model | Age, sex, BMI, ASA, diagnosis, comorbidities, surgerical approach, duration of surgery, hip type, Dorr type, revision time and type |

| Budin et al[34], 2024 | Multivariable logistic regression | Age, sex, tobacco use, and LOS |

| Magruder et al[32], 2024 | Logistical regression | Age, sex, and CCI |

| Aro et al[13], 2012 | KM and logistic-regression model | Age, BMI, local BMD, T-score of the operated hip, and canal flare index |

| Electricwala et al[23], 2016 | Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons | BMI |

| Münger et al[14], 2006 | Multivariate conditional logistic regressions | Age, sex, indication for surgery, height, weight, BMI, and mobility level |

| Layson et al[29], 2024 | Multivariate logistic regressions | Age, sex, alcohol abuse, CCI, diabetes, obesity, CKD, history of cancer and tumors, CHF, CVD, RA, liver disease, and tobacco use |

| Clauss et al[58], 2013 | Multivariable Cox regression analysis with stepwise variable selection | Age, sex, primary diagnosis, type of implant, implant material, stem offset, stem size, type of cup, and head diameter |

| Khatod et al[43], 2014 | Multivariate Cox models | Age, gender, race, BMI, diabetes, ASA, implants, techniques, surgeons, and hospital factors |

| Stelmach et al[45], 2015 | Cox regression models | Age, BMI, gender, BCL2-938 polymorphisms |

| Wedemeyer et al[44], 2009 | Cox regression models | Age, gender, weight, height, BMI, BCL2-938C>A and CALCA-1786T>C polymorphisms, defects of acetabular and femoral |

| Lee et al[56], 2024 | Multivariate logistic regression model | Age, stem type, sex, BMI, diagnosis, CCI, stem alignment, and canal fill ratio |

| Lunn et al[33], 2005 | Logistic regression analysis | Age, HFE gene mutations C282Y and H63D genotype |

| Halawi et al[26], 2016 | Multivariate logistic regression | Age, sex, BMI, CCI, diagnosis, approach, prior surgery, head size, articulation |

| Boyer et al[19], 2019 | Cox multivariate regression model | BMI, gender, age, diabetes, weight, height |

The methodological quality was assessed using standardized tools: The NOS for cohort studies and the AHRQ checklist for case-control studies. The NOS evaluation revealed that most cohort studies demonstrated high methodological quality (scores 6-8), with particularly rigorous outcome assessment methods. However, variability was observed in their approaches to confounding factor adjustment and cohort selection (Table 3). Similarly, the AHRQ assessment of three case-control studies indicated inconsistencies, primarily in sampling transparency and the reporting of analysis exclusions (Table 4). The overall high quality of the included studies strengthens the reliability of our findings.

| Ref. | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | |||||

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | ||

| Davis et al[61], 2020 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Benson et al[35], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Bordini et al[15], 2007 | 1 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Jud et al[42], 2024 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Wagener et al[62], 2024 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Budin et al[34], 2024 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Magruder et al[32], 2024 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Aro et al[13], 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Electricwala et al[23], 2016 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Layson et al[29], 2024 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Clauss et al[58], 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Khatod et al[43], 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Stelmach et al[45], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Wedemeyer et al[44], 2009 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Lee et al[56], 2024 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Halawi et al[26], 2016 | 1 | N/A | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Boyer et al[19], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

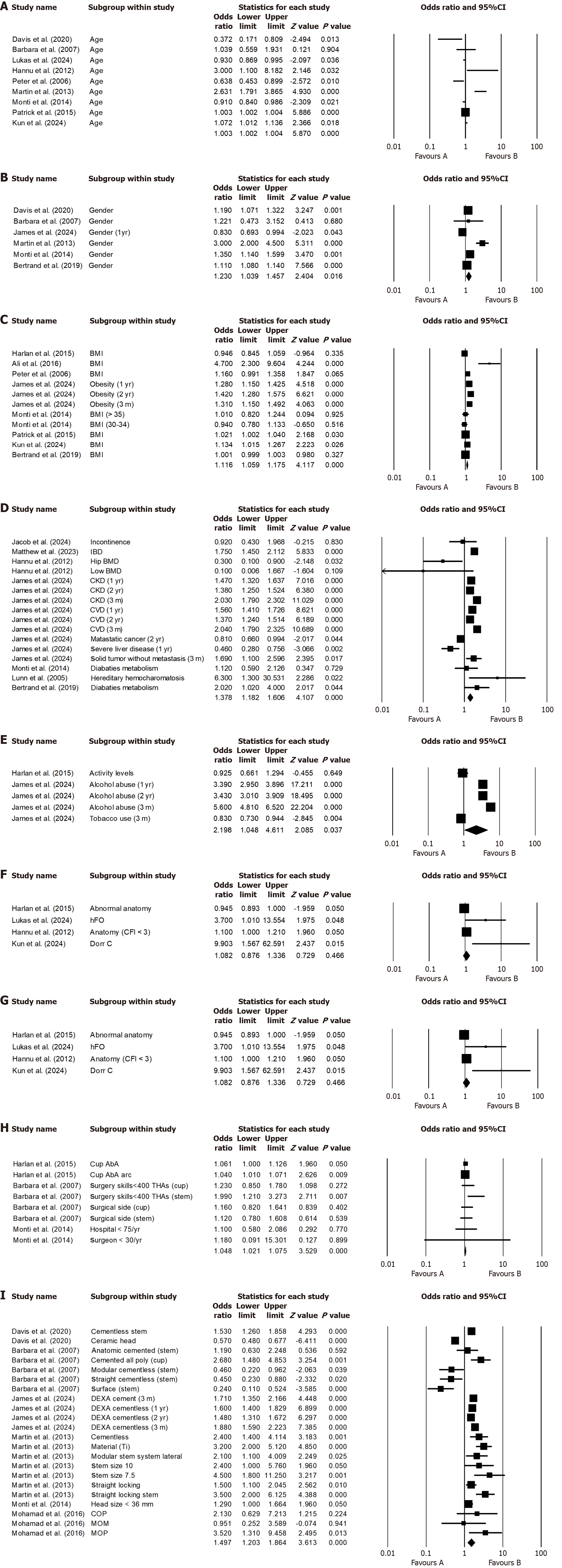

The meta-analysis synthesized multiple factors associated with aseptic loosening, presenting pooled OR with 95%CI, heterogeneity measures, and statistical significance (Table 5). The strongest risk factors included BMI, CCI, prosthesis type, and lifestyle factors, all demonstrating significantly elevated OR. Protective factors such as race and genotype showed reduced OR. Non-significant factors including age and anatomical characteristics showed no clinically meaningful associations. Further more, we also performed sensitivity analyses and the results were robust.

| Factors | Pooled OR | LL 95%CI | UL 95%CI | P value | I2 | Effects model |

| Age | 0.998 | 0.911 | 1.093 | 0.964 | 86.033 | R |

| Gender (male) | 1.232 | 1.039 | 1.460 | 0.016 | 87.230 | R |

| BMI | 1.116 | 1.059 | 1.175 | < 0.001 | 91.057 | R |

| CCI | 1.378 | 1.182 | 1.606 | < 0.001 | 88.230 | R |

| Lifestyle | 2.198 | 1.048 | 4.611 | 0.037 | 99.140 | R |

| Diagnosis | 1.162 | 1.009 | 1.338 | 0.037 | 61.546 | R |

| Anatomy | 1.082 | 0.876 | 1.336 | 0.466 | 82.582 | R |

| Race | 0.445 | 0.302 | 0.655 | < 0.001 | 0.000 | F |

| Genetype | 0.723 | 0.617 | 0.849 | < 0.001 | 0.000 | F |

| Surgical skills | 1.048 | 1.021 | 1.075 | < 0.001 | 12.78 | F |

| Prosthesis | 1.497 | 1.203 | 1.864 | < 0.001 | 89.958 | R |

Age demonstrated no significant correlation (OR = 0.998, 95%CI: 0.911-1.093, P = 0.964) in Figure 2A. The analysis revealed that age was not significantly associated with aseptic loosening (OR = 0.998, 95%CI: 0.911-1.093, P = 0.964), which suggested that age did not play a significant role in influencing the aseptic loosening within the examined population.

Male sex was significantly associated with a 23.2% higher risk of the aseptic loosening, as evidenced by an OR of 1.232 (95%CI: 1.039-1.460, P = 0.016) (Figure 2B). This finding suggests that male participants had a notably elevated risk compared to their female counterparts in the study population.

The study revealed a significant association between BMI and aseptic loosening, demonstrating a strong positive relationship (OR = 1.116, 95%CI: 1.059-1.175, P < 0.001). This indicates that each unit increase in BMI was associated with an 11.6% higher risk. Figure 2C further supports a potential causal relationship between elevated BMI levels and increased risk of the aseptic loosening.

Higher comorbidity burden was significantly associated with an elevated risk of the aseptic loosening, as evidenced by an OR of 1.378 (95%CI: 1.182-1.606), indicating a strong relationship between comorbidity burden and increased risk. The Figure 2D suggested that patients with a higher comorbidity burden face a substantially greater likelihood of experiencing the risk of the aseptic loosening.

The study revealed that a specific lifestyle factor was significantly associated with a 2.2-fold elevation in disease risk of aseptic loosening, as evidenced by an OR of 2.198 (95%CI: 1.048-4.611, P = 0.037). Figure 2E shows the OR of lifestyle for aseptic loosening after pTHA. This association suggests that individuals adhering to these lifestyles may face more than double the risk compared to those who do not.

The statistical analysis revealed a marginally significant association between diagnosis and aseptic loosening, with an OR of 1.162 (95%CI: 1.009-1.338, P = 0.037) (Figure 2F). This suggests a modest yet potentially clinically relevant relationship that warrants further investigation. In contrast, anatomical factors demonstrated no statistically significant association (OR = 1.082, 95%CI: 0.876-1.336, P = 0.466) in Figure 2G, indicating these variables may not be meaningful predictors in this context. Notably, non-white race showed substantial protective effects against the risk of aseptic loosening, with significantly reduced odds (OR = 0.445, 95%CI: 0.302-0.655, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Figure 1). This pronounced racial disparity highlights the potential influence of sociodemographic or genetic factors that merit additional exploration in future studies.

The analysis demonstrated that higher levels of surgical skills were associated with a modest but statistically significant reduction in aseptic loosening risk with OR = 0.952, 95%CI: 0.928-0.979, P < 0.001), as illustrated in Figure 2H. This inverse relationship suggests that for each unit increase in surgical proficiency, patients experienced approximately a 4.8% decrease in the likelihood of aseptic loosening. These findings underscore the importance of surgical expertise as a potentially modifiable factor in reducing risk of aseptic loosening.

The selection of prosthesis type demonstrated a substantial influence on clinical outcomes, as evidenced by a statistically significant OR of 1.497 (95%CI: 1.203-1.864, P < 0.001). This robust association, illustrated in Figure 2I, indicates that appropriate prosthesis selection increased the likelihood of positive treatment outcomes by approximately 50%, highlighting the critical importance of individualized implant choice in achieving optimal surgical results. The narrow 95%CI and highly significant P value further strengthen the reliability of these findings, suggesting that prosthesis selection should be carefully considered in clinical decision-making.

pTHA demonstrates excellent long-term survivorship, yet aseptic loosening remains a significant complication results from either inadequate initial fixation or progressive mechanical fixation loss[9-11]. Given the varying degrees of association among known factors, a comprehensive understanding of these elements is essential for prevention, necessitating systematic evaluation after pTHA. Our systematic review analyzed aseptic loosening incidence among 520789 pTHA patients, revealing an overall rate of 1.96%. The findings underscore the multifactorial etiologies involving patient characteristics, surgical techniques, and prosthesis selection. Multivariate analysis identified risk factors: Elevated BMI (OR = 1.116, P < 0.001), comorbidities (OR = 1.378, P < 0.001), prosthesis characteristics (OR = 1.497, P < 0.001), and lifestyles (OR = 2.198, P = 0.037). Protective factors included non-white ethnicity (OR = 0.445, P < 0.001) and favorable genetic predisposition (OR = 0.723, P < 0.001). Male showed modest risk elevation (OR = 1.232, P = 0.016), while age and anatomical factors demonstrated no significant association. Surgical experience exhibited a slight protective effect (OR = 1.048, P < 0.001). These results highlight the complex interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in aseptic loosening pathogenesis, emphasizing the need for personalized risk assessment and management strategies.

Age: Studies suggest that age influences the risk of aseptic loosening[12,13]; however, our study did not identify a significant association (OR = 0.998, 95%CI: 0.911-1.093). Younger patients may face a higher risk of aseptic loosening due to increased activity levels, which can induce greater dynamic mechanical stress at the bone-implant interface, accelerating micromotion, wear, and prosthetic fatigue failure. In contrast, elderly patients typically exhibit a lower risk, attributable to reduced mechanical loading from decreased activity and age-related anatomical changes, such as femoral medullary cavity narrowing, diminished bone remodeling capacity, and osteoporosis-induced alterations in bone-prosthesis congruence. Whereas younger patients are more prone to failure from high-cyclic loading, elderly patients may experience cement-bone interface failures due to poor bone quality. Our findings indicate no significant correlation between age and aseptic loosening risk, suggesting that age alone may not be a determining factor. This discrepancy with prior studies could stem from limited cohort sizes, insufficient raw data, or our inclusion criteria restricting analysis. Future investigations should employ larger cohorts to clarify this potential association. These results highlight the importance of age-specific clinical management: Younger and active patients may benefit from closer surveillance and activity modification, whereas elderly patients with compromised bone quality may require careful preoperative assessment to optimize outcomes.

Gender: Our study reveals sex-specific differences in pTHA outcomes, contrasting with prior research[14-17]. While female patients demonstrated higher aseptic loosening risks potentially attributable to smaller implant sizes (particularly femoral heads), male patients showed significantly greater failure risk (OR = 1.232, 95%CI: 1.039-1.460, P = 0.016), consistent with previous findings from Inacio et al[18]. These discrepancies may stem from variations in study populations, follow-up durations, and failure definitions. Mechanistically, males increased aseptic loosening risk appears multifactorial. As for biomechanical factors, higher cumulative prosthetic loads from greater activity levels and BMI accelerate micromotion-induced osteolysis. As for anatomical considerations, larger femoral heads may paradoxically reduce stability. As for biological differences, gender-specific bone remodeling responses to mechanical stress may occur, potentially influenced by differential bone mineral density (BMD) patterns or protective factors against infectious loosening or differential BMD patterns. These findings underscore the importance of sex-specific surgical approaches, including optimized component sizing, stability enhancement techniques, and personalized activity

BMI: Consistent with previous researches[14,19-23], our meta-analysis demonstrates a significant dose-dependent association between elevated BMI and increased risk of aseptic loosening (OR = 1.116, 95%CI: 1.059-1.175, P < 0.001). Biomechanically, excessive body weight amplifies joint reaction forces, accelerating polyethylene wear and periprosthetic osteolysis through overload, while simultaneously increasing shear stresses at bone-implant interfaces, thereby promoting fretting wear and micromotion. Furthermore, adipose-derived inflammatory cytokines may act synergistically with mechanical factors to exacerbate bone resorption through metabolic pathways. These findings underscore the critical importance of perioperative BMI management in clinical practice. Encourage sustained weight reduction through diet, low-impact exercise, and fall-prevention support to minimize repetitive mechanical stress.

CCI: A higher comorbidity burden, as assessed by the CCI, significantly increased the odds of implant loosening (OR = 1.378, 95%CI: 1.182-1.606, P < 0.001), consistent with prior studies linking CCI to aseptic loosening[21,24-28]. This association may be attributed to multiple mechanisms, including compromised bone quality in patients with osteoporosis or low BMD, which elevates complication risks[13,29-31]. Implant-derived wear debris triggers macrophage activation and periprosthetic osteoclast-mediated bone resorption through an aseptic inflammatory response, driven by cellular and humoral factors. These findings suggest a shared inflammatory pathway underlying implant failure, warranting further experimental investigation. Comorbidities may converge on common pathways, such as poor initial fixation due to osteoporotic bone (increasing micromotion), impaired osseointegration, and chronic inflammation that exacerbates mechanical stress. Additionally, nutritional deficiencies, iron overload, and hyperglycemia may further hinder bone-implant integration[32,33]. Indirect factors, such as urinary tract infection-related bacteremia in incontinent patients, could also contribute to prosthetic failure by seeding the implant interface reported by Budin et al[34], underscoring the complex relationship between systemic health and implant longevity. Preoperative risk assessment and long-term monitoring are essential to mitigate loosening and manage bone resorption progression. Conditions like diabetes, osteoporosis, or chronic inflammatory disorders impair bone remodeling and compromise implant fixation. Optimize metabolic control, manage BMD, and coordinate perioperative care (e.g., endocrinology, rheumatology consults, and urinary infection) to maintain bone quality and reduce the relevant risk[35].

Lifestyle: Multiple studies have established a link between elevated physical activity levels and increased rates of aseptic loosening[36,37], though some reports found no significant association Malik et al[38]. Our study corroborates these findings, demonstrating that smoking combined with high physical activity more than doubles the risk of aseptic loosening (OR = 2.198, 95%CI: 1.048-4.611, P = 0.037). Biomechanical analysis reveals that excessive motion - particularly during dynamic movements requiring extreme hip range of motion - exacerbates prosthetic wear through three key mechanisms: Increased cyclic loading on the acetabular component, especially in edge-loading positions; accelerated polyethylene wear due to sustained impingement during extreme flexion/abduction; and progressive micromotion at the bone-implant interface caused by unbalanced force distribution. These findings highlight the need for activity-specific rehabilitation protocols, particularly for patients engaged in occupations or sports involving extreme hip kinematics. Moreover, smoking further compounds the risk by impairing bone healing, creating a hazardous synergy in which mechanical stressors exceed the prosthesis’s fatigue resistance while compromised osseointegration fails to maintain stable fixation. Therefore, personalized rehabilitation strategies should be implemented. Moreover, promote smoking cessation, moderate alcohol use, and adherence to physiotherapy with progressive strengthening to sustain implant stability.

Diagnosis: Multiple studies have demonstrated the significance of preoperative diagnosis in predicting aseptic loosening[17,39,40]. Our findings corroborate these observations, (OR = 1.162, 95%CI: 1.009-1.338, P = 0.037). Potential underlying mechanisms encompass systemic/Local inflammation, peri-prosthetic microenvironment alterations, disease activity levels, postoperative mobility restrictions, glucocorticoid effects, heightened immune responses, and bone metabolism disturbances. Clinically, these findings underscore the importance of rigorous disease management, appropriate biologic agent use, and routine radiographic surveillance - even in asymptomatic patients - to facilitate early detection of component loosening. Future research should investigate targeted modulation of inflammatory pathways to enhance prosthesis longevity. Crucially, preoperative diagnosis should not singularly guide fixation strategy selection, as bone quality and patient activity levels appear more predictive of loosening risk than the original arthropathy etiology.

Anatomy: Existing research demonstrates that anatomical variations impact implant longevity[41,42]; however, our meta-analysis found no statistically significant association (OR = 1.082, 95%CI: 0.876-1.336, P = 0.466), potentially due to limited studies available for pooled analysis. Nevertheless, three key mechanisms underscore the clinical relevance of anatomical factors in implant loosening: Poor initial fixation - dysplastic acetabuli [low central-endge (CE) angle] or stovepipe femurs, e.g., low canal flare index (CFI) reduce implant-bone contact, increasing micromotion; compromised load transfer - osteoporotic bone exhibits inadequate stress shielding resistance, causing subsidence, while distal fixation dependence in stovepipe femurs promotes proximal bone resorption; and implant-bone mismatch - anatomic stems fail in non-anatomic canals, and excessive stem rigidity elevates fracture risk in osteoporotic bone. Although our quantitative synthesis showed nonsignificant results, we recommend thorough preoperative assessment of CE angle, CFI, and Dorr classification to guide implant selection. High-risk patients (e.g., Dorr C/Low CFI) may benefit from cemented stems or extensively porous-coated designs, while acetabular dysplasia cases might require augmentation (e.g., bone grafts/jumbo cups). Future research should investigate patient-specific implants for extreme anatomies, finite element analyses of load distribution across femoral morphologies, and bone-strengthening therapies to enhance fixation in compromised bone stock.

Ethnicity and polymorphisms: In addition to the factors included in our meta-analysis, ethnicity and genetic polymorphisms were also found to significantly influence aseptic loosening risk. While existing studies report conflicting findings regarding racial disparities between White and Black populations[16,43,44], our analysis demonstrates a protective effect in non-White populations (OR = 0.445, 95%CI: 0.302-0.655, P < 0.001), with Hispanic (HR = 0.49) and Asian (HR = 0.35) patients showing particularly lower risks compared to White patients. These ethnic disparities may arise from variations in femoral geometry, BMD, activity patterns, and genetic predispositions affecting bone remodeling. However, the limited number of studies examining racial factors (only one reporting OR) underscores the need for standardized demographic reporting to minimize bias and enhance comparability. Furthermore, genetic polymorphisms exhibited a significant protective effect (OR = 0.723, 95%CI: 0.617-0.849, P < 0.001)[45,46]. potentially mediated through biological pathways involving macrophage apoptosis regulation (e.g., BCL2 expression) and neuropeptide-mediated osteogenic signaling, which collectively influence wear particle-induced inflammation and bone remodeling. Future studies should systematically report both ethnicity and genetic polymorphisms to better elucidate their roles in aseptic loosening.

Research consistently identifies surgical technique and operator expertise as primary determinants of early implant loosening[47-52]. Our study corroborates these findings, demonstrating a significant protective effect against aseptic loosening (OR = 1.048, 95%CI: 1.021-1.075, P < 0.001), where each incremental improvement in technical proficiency corresponded to reduced failure risk. Experienced surgeons achieve superior component positioning, including optimal acetabular inclination and femoral stem alignment, thereby minimizing edge loading and abnormal stress distributions. Next, meticulous bone preparation - particularly preservation of cancellous bone architecture and proper cementation technique - enhances primary stability. Conversely, less experienced operators demonstrate higher rates of technical errors such as varus stem placement, incomplete cement mantles, and inadequate impaction grafting, all of which predispose to early micromotion and compromised osseointegration. These observations highlight the clinical relevance of structured surgical training programs and volume-outcome relationships in pTHA. However, heterogeneity in volume classification methodologies may account for discrepancies across studies. Surgeon fellowship training may require modification to mitigate potential risks.

Multiple studies have investigated the influence of implant characteristics on aseptic loosening risk[53-61]. Prosthesis-related factors demonstrated statistically significant yet inconsistent effects (OR = 1.497, 95%CI: 1.203-1.864, P < 0.001). The underlying mechanisms may be explained by several factors. First, fixation method selection significantly impacts outcomes: Cementless stems exhibit higher early failure rates than cemented fixation, likely due to differences in proximal load transfer efficiency. Second, bearing surface materials play a crucial role, with ceramic heads demonstrating lower wear rates and consequently reduced particle-induced osteolysis risk compared to metal counterparts. Third, component positioning affects long-term stability; excessive acetabular abduction angles may increase loading in Charnley zones II and III, potentially compromising fixation[62].

While modern designs such as hydroxyapatite-coated stems show enhanced osseointegration, certain configurations like metal-on-metal articulations exhibit time-dependent failure patterns reported by Khatod et al[63]. These findings highlight the critical importance of patient-specific prosthesis selection: Cementless fixation may be preferable for younger patients with adequate bone stock, whereas ceramic bearings suit active individuals. Additionally, precise component alignment is essential for long-term success. Tailor component selection to patient anatomy and bone stock, ensure precise alignment, and favor proven fixation techniques to achieve durable osseointegration. Given the current limitations in high-quality evidence, further research is warranted to elucidate risk factors associated with aseptic loosening in contemporary implant designs, and determine whether modification of identified risk factors can reduce aseptic loosening incidence following pTHA.

This study represents the most up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis examining factors associated with aseptic loosening following pTHA. A key strength is the inclusion of over 520789 participants, enhancing the statistical power of our findings. Additionally, the diversity of assessed factors-encompassing patient-, surgeon-, and implant-related variables - improves the generalizability of our results. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, while meta-analysis cannot establish causal mechanisms, we mitigated potential bias and improved efficiency through multiple imputation techniques. Second, our analysis was restricted to English-language studies from four databases, and methodological quality varied significantly across included studies. Many lacked raw OR data, preventing the calculation of certain relevant factors. Nevertheless, our stringent eligibility criteria ensured a baseline level of evidence, supporting the plausibility of our conclusions. Additionally, some factors (e.g., race) had insufficient data for robust meta-analysis, warranting further investigation. Third, inconsistencies in reported factors across studies may reflect differences in methodology, leading to the exclusion of some relevant but unsuitable data. Fourth, prospective studies on loosening risk factors remain scarce, however, retrospective studies were deemed acceptable for our prognostic analysis.

The differential significance of these variables underscores the complexity of the aseptic loosening and the need for multifactorial analysis. We focused on patient-, surgeon-, and implant-related factors, other contributors may exist. Despite numerous studies examining these variables, insufficient raw data precluded stratified analyses. Furthermore, due to the extensive timeframe and variability in the included studies, we could not thoroughly assess evolving trends in polyethylene processing, sterilization methods, implant design, or surgical techniques. A more precise analysis would require a large, homogenous cohort with uniform implant designs, surgical approaches, and material properties. Given the current evidence, future studies must prioritize methodological rigor to better delineate these risk factors.

A thorough understanding of risk factors is essential for clinical decision-making in pTHA, as it enables the identification of patients at increased risk of aseptic loosening. Surgeons should counsel pTHA patients regarding this potential complication. Such awareness facilitates targeted interventions for high-risk individuals, including personalized treatment plans, optimized surgical techniques, and improved prosthetic designs to reduce loosening incidence.

| 1. | Sowers CB, Carrero AC, Cyrus JW, Ross JA, Golladay GJ, Patel NK. Return to Sports After Total Hip Arthroplasty: An Umbrella Review for Consensus Guidelines. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51:271-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Duman S, Çamurcu İY, Uçpunar H, Sevencan A, Akıncı Ş, Şahin V. Comparison of clinical characteristics and 10-year survival rates of revision hip arthroplasties among revision time groups. Arch Med Sci. 2021;17:382-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Longo UG, Papalia R, Salvatore G, Tecce SM, Jedrzejczak A, Marcozzi M, Piergentili I, Denaro V. Epidemiology of revision hip replacement in Italy: a 15-year study. BMC Surg. 2022;22:355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chougle A, Hemmady MV, Hodgkinson JP. Severity of hip dysplasia and loosening of the socket in cemented total hip replacement. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hauer G, Rasic L, Klim S, Leitner L, Leithner A, Sadoghi P. Septic complications are on the rise and aseptic loosening has decreased in total joint arthroplasty: an updated complication based analysis using worldwide arthroplasty registers. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2024;144:5199-5204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kolundzić R, Orlić D. [Particle disease--aseptic loosening of the total hip endoprosthesis]. Lijec Vjesn. 2008;130:16-20. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Zinar R, Schmalzried TP. Why hip implants fail: Patient, surgeon, or device? Semin Arthroplasty. 2015;26:118-120. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7062] [Cited by in RCA: 5601] [Article Influence: 1120.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 9. | McArthur BA, Scully R, Patrick Ross F, Bostrom MPG, Falghren A. Mechanically Induced Periprosthetic Osteolysis: A Systematic Review. HSS J. 2019;15:286-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Athanasou NA. The pathobiology and pathology of aseptic implant failure. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pegios VF, Kenanidis E, Tsotsolis S, Potoupnis M, Tsiridis E. Bisphosphonates' use and risk of aseptic loosening following total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. EFORT Open Rev. 2023;8:798-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Carender CN, Bothun CE, Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT, Abdel MP, Bedard NA. Contemporary Aseptic Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients ≤50 Years of Age: Results of >500 Cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2024;106:1108-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Aro HT, Alm JJ, Moritz N, Mäkinen TJ, Lankinen P. Low BMD affects initial stability and delays stem osseointegration in cementless total hip arthroplasty in women: a 2-year RSA study of 39 patients. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:107-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Münger P, Röder C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Busato A. Patient-related risk factors leading to aseptic stem loosening in total hip arthroplasty: a case-control study of 5,035 patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:567-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bordini B, Stea S, De Clerico M, Strazzari S, Sasdelli A, Toni A. Factors affecting aseptic loosening of 4750 total hip arthroplasties: multivariate survival analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin YS, DeClercq JJ, Ayers GD, Gilmor RJ, Collett G, Jain NB. Incidence and Clinical Risk Factors of Post-Operative Complications following Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: A 10-Year Population-Based Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2023;13:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cherian JJ, Jauregui JJ, Banerjee S, Pierce T, Mont MA. What Host Factors Affect Aseptic Loosening After THA and TKA? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:2700-2709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Inacio MC, Ake CF, Paxton EW, Khatod M, Wang C, Gross TP, Kaczmarek RG, Marinac-Dabic D, Sedrakyan A. Sex and risk of hip implant failure: assessing total hip arthroplasty outcomes in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:435-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Boyer B, Bordini B, Caputo D, Neri T, Stea S, Toni A. What are the influencing factors on hip and knee arthroplasty survival? Prospective cohort study on 63619 arthroplasties. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105:1251-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Peters RM, van Steenbergen LN, Stewart RE, Stevens M, Rijk PC, Bulstra SK, Zijlstra WP. Patient Characteristics Influence Revision Rate of Total Hip Arthroplasty: American Society of Anesthesiologists Score and Body Mass Index Were the Strongest Predictors for Short-Term Revision After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:188-192.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Szymski D, Walter N, Krull P, Melsheimer O, Schindler M, Grimberg A, Alt V, Steinbrueck A, Rupp M. Comparison of mortality rate and septic and aseptic revisions in total hip arthroplasties for osteoarthritis and femoral neck fracture: an analysis of the German Arthroplasty Registry. J Orthop Traumatol. 2023;24:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schiffner E, Latz D, Thelen S, Grassmann JP, Karbowski A, Windolf J, Jungbluth P, Schneppendahl J. Aseptic Loosening after THA and TKA - Do gender, tobacco use and BMI have an impact on implant survival time? J Orthop. 2019;16:269-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Electricwala AJ, Narkbunnam R, Huddleston JI 3rd, Maloney WJ, Goodman SB, Amanatullah DF. Obesity is Associated With Early Total Hip Revision for Aseptic Loosening. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:217-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rysinska A, Sköldenberg O, Garland A, Rolfson O, Aspberg S, Eisler T, Garellick G, Stark A, Hailer N, Gordon M. Aseptic loosening after total hip arthroplasty and the risk of cardiovascular disease: A nested case-control study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ng MK, Kobryn A, Emara AK, Krebs VE, Mont MA, Piuzzi NS. Decreasing trend of inpatient mortality rates of aseptic versus septic revision total hip arthroplasty: an analysis of 681,034 cases. Hip Int. 2023;33:1063-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Halawi MJ, Brigati D, Messner W, Brooks PJ. Total hip arthroplasty in patients 55 years or younger: Risk factors for poor midterm outcomes. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9:103-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kleeman-Forsthuber L, Vigdorchik JM, Pierrepont JW, Dennis DA. Pelvic incidence significance relative to spinopelvic risk factors for total hip arthroplasty instability. Bone Joint J. 2022;104-B:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Goh GS, Shohat N, Abdelaal MS, Small I, Thomas T, Ciesielka KA, Parvizi J. Serum Glucose Variability Increases the Risk of Complications Following Aseptic Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104:1614-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Layson JT, Hameed D, Dubin JA, Moore MC, Mont M, Scuderi GR. Patients with Osteoporosis Are at Higher Risk for Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures and Aseptic Loosening Following Total Hip Arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2024;55:311-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Solomon LB, Studer P, Abrahams JM, Callary SA, Moran CR, Stamenkov RB, Howie DW. Does cup-cage reconstruction with oversized cups provide initial stability in THA for osteoporotic acetabular fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3811-3819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gallo J, Havranek V, Zapletalova J, Lostak J. Male gender, Charnley class C, and severity of bone defects predict the risk for aseptic loosening in the cup of ABG I hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Magruder ML, Parsa S, Gordon AM, Ng M, Wong CHJ. Inflammatory bowel disease patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty have higher odds of implant-related complications. Hip Int. 2024;34:498-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lunn JV, Gallagher PM, Hegarty S, Kaliszer M, Crowe J, Murray P, Bouchier-Hayes D. The role of hereditary hemochromatosis in aseptic loosening following primary total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:542-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Budin JS, Waters TL, Collins LK, Cole MW, Winter JE, Delvadia BP, Iloanya MC, Sherman WF. Incontinence Is an Independent Risk Factor for Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2024;27:101355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Benson TE, Andersen IT, Overgaard S, Fenstad AM, Lie SA, Gjertsen JE, Furnes ON, Pedersen AB. Association of perioperative thromboprophylaxis on revision rate due to infection and aseptic loosening in primary total hip arthroplasty - new evidence from the Nordic Arthroplasty Registry Association (NARA). Acta Orthop. 2022;93:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ollivier M, Frey S, Parratte S, Flecher X, Argenson JN. Does impact sport activity influence total hip arthroplasty durability? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:3060-3066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Gschwend N, Frei T, Morscher E, Nigg B, Loehr J. Alpine and cross-country skiing after total hip replacement: 2 cohorts of 50 patients each, one active, the other inactive in skiing, followed for 5-10 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Malik MH, Gray J, Kay PR. Early aseptic loosening of cemented total hip arthroplasty: the influence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and smoking. Int Orthop. 2004;28:211-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Böhler C, Weimann P, Alasti F, Smolen JS, Windhager R, Aletaha D. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity and the risk of aseptic arthroplasty loosening. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Schreiner MM, Straub J, Apprich S, Staats K, Windhager R, Aletaha D, Böhler C. The influence of biological DMARDs on aseptic arthroplasty loosening: a retrospective cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024;63:970-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, Wood TJ; the Hamilton Arthroplasty Group. Intermediate to Long-Term Outcomes and Causes of Aseptic Failure of an At-Risk Femoral Stem. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104:896-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Jud L, Rüedi N, Dimitriou D, Hoch A, Zingg PO. High femoral offset as a risk factor for aseptic femoral component loosening in cementless primary total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2024;48:1217-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Khatod M, Cafri G, Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW. Risk factors for total hip arthroplasty aseptic revision. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1412-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wedemeyer C, Kauther MD, Hanenkamp S, Nückel H, Bau M, Siffert W, Bachmann HS. BCL2-938C>A and CALCA-1786T>C polymorphisms in aseptic loosened total hip arthroplasty. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:250-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Stelmach P, Wedemeyer C, Fuest L, Kurscheid G, Gehrke T, Klenke S, Jäger M, Kauther MD, Bachmann HS. The BCL2 -938C>A Promoter Polymorphism Is Associated with Risk for and Time to Aseptic Loosening of Total Hip Arthroplasty. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Streit MR, Haeussler D, Bruckner T, Proctor T, Innmann MM, Merle C, Gotterbarm T, Weiss S. Early Migration Predicts Aseptic Loosening of Cementless Femoral Stems: A Long-term Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1697-1706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Godoy-Santos AL, D'Elia CO, Teixeira WJ, Cabrita HB, Camanho GL. Aseptic loosening of total hip arthroplasty: preliminary genetic investigation. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:297-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Miettinen SS, Mäkinen TJ, Laaksonen I, Mäkelä K, Huhtala H, Kettunen J, Remes V. Early aseptic loosening of cementless monoblock acetabular components. Int Orthop. 2017;41:715-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Amstutz HC, Le Duff MJ. Aseptic loosening of cobalt chromium monoblock sockets after hip resurfacing. Hip Int. 2015;25:466-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zampelis V, Flivik G, Kesteris U. No effect of femoral canal jet-lavage on the stability of cementless stems in primary hip arthroplasty: a randomised RSA study with 6 years follow-up. Hip Int. 2020;30:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | de Waard S, Sierevelt IN, Jonker R, Hoornenborg D, van der Vis HM, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Haverkamp D. The migration pattern and initial stability of the Optimys short stem in total hip arthroplasty: a prospective 2-year follow-up study of 33 patients with RSA. Hip Int. 2021;31:507-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Dammerer D, Keiler A, Putzer D, Lenze F, Liebensteiner M, Thaler M. Different wear in two highly cross-linked polyethylene liners in THA: wear analysis with EBRA. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141:1591-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lex JR, Evans S, Parry MC, Jeys L, Stevenson JD. Acetabular complications are the most common cause for revision surgery following proximal femoral endoprosthetic replacement : what is the best bearing option in the primary and revision setting? Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B:1633-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Vercruysse LYG, Milne LP, Harries DTC, de Steiger RN, Wall CJ. Lower Revision Rates and Improved Stability With a Monoblock Ceramic Acetabular Cup. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39:985-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | van der Lelij TJN, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Kaptein BL, Koster LA, Ljung P, Nelissen RGHH, Toksvig-Larsen S. Migration and clinical outcomes of a novel cementless hydroxyapatite-coated titanium acetabular shell: two-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial using radiostereometric analysis. Bone Joint J. 2024;106-B:136-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lee KH, Hung YT, Chang CY, Wang JC, Tsai SW, Chen CF, Wu PK, Chen WM. The cementless taper wedge vs. fit-and-fill stem in primary total hip arthroplasty: risk of stem-related complication differs across Dorr types. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2024;144:2839-2847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Schwarze J, Theil C, Gosheger G, Dieckmann R, Moellenbeck B, Ackmann T, Schmidt-Braekling T. Promising results of revision total hip arthroplasty using a hexagonal, modular, tapered stem in cases of aseptic loosening. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Clauss M, Gersbach S, Butscher A, Ilchmann T. Risk factors for aseptic loosening of Müller-type straight stems: a registry-based analysis of 828 consecutive cases with a minimum follow-up of 16 years. Acta Orthop. 2013;84:353-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kannan A, Owen JR, Wayne JS, Jiranek WA. Loosely implanted cementless stems may become rotationally stable after loading. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2231-2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Müller U, Gautier E, Roeder C, Busato A. The relationship between cup design and the radiological signs of aseptic loosening in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Davis ET, Pagkalos J, Kopjar B. A higher degree of polyethylene irradiation is associated with a reduced risk of revision for aseptic loosening in total hip arthroplasties using cemented acetabular components: an analysis of 290,770 cases from the National Joint Registry of England, Wales, Northern Island and the Isle of Man. Bone Joint Res. 2020;9:563-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Wagener N, Pumberger M, Hardt S. Impact of fixation method on femoral bone loss: a retrospective evaluation of stem loosening in first-time revision total hip arthroplasty among two hundred and fifty five patients. Int Orthop. 2024;48:2339-2350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Khatod M, Inacio MC, Dell RM, Bini SA, Paxton EW, Namba RS. Association of Bisphosphonate Use and Risk of Revision After THA: Outcomes From a US Total Joint Replacement Registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3412-3420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/