Published online Jan 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.114078

Revised: October 30, 2025

Accepted: December 15, 2025

Published online: January 18, 2026

Processing time: 119 Days and 17.8 Hours

Salvage of the infected long stem revision total knee arthroplasty is challenging due to the presence of well-fixed ingrown or cemented stems. Reconstructive options are limited. Above knee amputation (AKA) is often recommended. We present a surgical technique that was successfully used on four such patients to convert them to a knee fusion (KF) using a cephalomedullary nail.

Four patients with infected long stem revision knee replacements that refused AKA had a single stage removal of their infected revision total knee followed by a KF. They were all treated with a statically locked antegrade cephalomedullary fusion nail, augmented with antibiotic impregnated bone cement. All patients had successful limb salvage and were ambulatory with assistive devices at the time of last follow-up. All were infection free at an average follow-up of 25.5 months (range 16-31).

Single stage cephalomedullary nailing can result in a successful KF in patients with infected long stem revision total knees.

Core Tip: Long stem infected revision total knees are challenging and are often treated with above the knee amputation. The authors provide a limb salvage technique for conversion to a knee fusion. A lateral approach to the femur and tibia with extended osteotomies allows for implant removal. A long cephalomedullary nail, supplemented with antibiotic cement, provides for a functional fusion. This a major surgical procedure that will likely involve blood transfusions and intensive care management, and post operative wound problems are common. However, if successful, patients can expect to walk with a shoe lift and a walking aide.

- Citation: Georgiadis GM, Arefi IA, Drees SM, Nair A, Wagner D, Lawrence AC. Cephalomedullary fusion nails for treatment of infected stemmed revision total knee arthroplasty: Four case reports. World J Orthop 2026; 17(1): 114078

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i1/114078.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.114078

Infection after a revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a devastating complication. It may often be the result of staged treatment of previous prosthetic infection. Chronic antibiotic suppression without surgery is usually not successful. Excisional arthroplasties are unstable and poorly tolerated but can be considered in selected patients[1]. Additional revision arthroplasty procedures can be considered. However not all infections can be successfully resolved, and some patients may not be medically able to undergo repeated surgeries. At that point, knee fusion (KF) or above knee amputation (AKA) are possible remaining options. The optimal treatment is a matter of debate, and becomes a shared decision between patients, their families and clinicians[2-6].

In the presence of persistent infection, AKA is the best procedure to eradicate infection[3]. However, it often is associated with the need for repeated surgeries, high mortality, and poor function[7-9]. Although some patients can be satisfied with an AKA[10,11], others will not accept this procedure. KF for treatment of an infected total knee can be associated with significant complications[12,13]. Despite this it can be a durable solution that is associated with better overall function than an AKA[6,7,14,15].

We present four patients with persistent infected revision stemmed total knee arthroplasties in which an AKA was recommended. All were painful and had undergone previous attempts at resolution of their infection. Each refused an above the knee amputation.

Case 1: A 73-year-old male presented with right prosthetic knee pain, inability to ambulate and sepsis.

Case 2: A 78-year-old female presented with right prosthetic knee pain, swelling and inability to ambulate.

Case 3: A 59-year-old male presented with right prosthetic knee pain and inability to ambulate.

Case 4: An 84-year-old male presented with left revision prosthetic knee pain, inability to ambulate and sepsis.

Each presented with pain, persistent infection as documented with aspirate culture and laboratory studies.

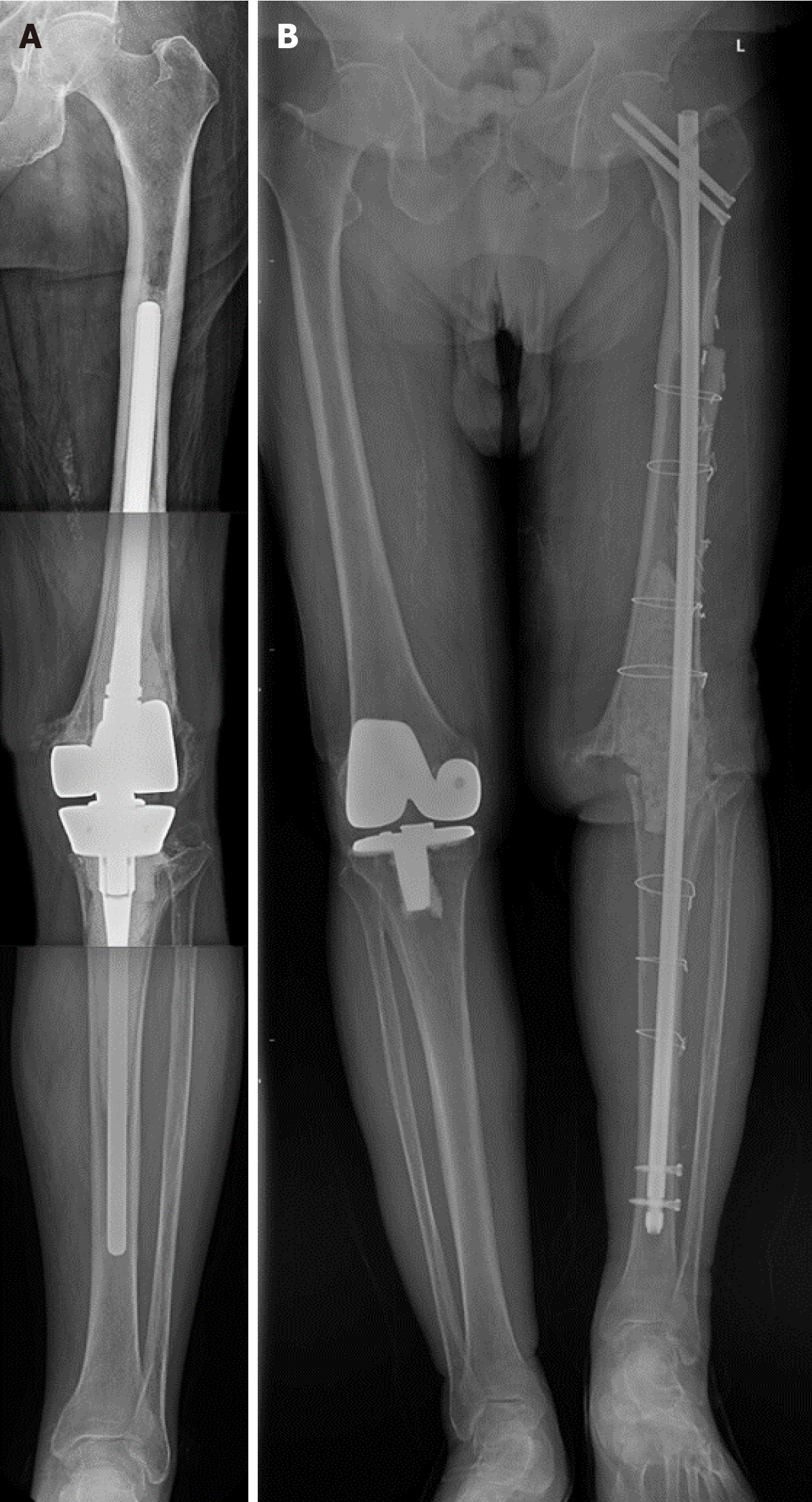

Case 1, 2 and 3 had undergone numerous previous surgeries (Table 1). Case 4 (an 84-year-old man) with multiple medical comorbidities including chronic kidney disease and numerous surgeries on his left prosthetic knee had a long stem revision rotating hinge prosthesis in place (Figure 1A). He developed recurrent infection that did not respond to arthrotomy, exchange of the articulating components, and intravenous antibiotics. He became septic and an urgent AKA was recommended. Both he and his family refused amputation, but did consent to a KF.

| Case | Age | Sex | BMI (kg/m2) | Comorbidities | Prior knee surgeries | Description of surgeries (year) | Previous post-operative infective organism |

| 1 | 73 | M | 63 | Morbid obesity; coronary artery disease; type 2 diabetes; atrial fibrillation neuropathy/chronic ipsilateral heel sore; hypertension; chronic venous stasis - right leg; sleep apnea; chronic anemia | 4 | Initial right TKA (2010); articulating antibiotic cement spacer (2016); long stem revision (2016); debridement with prosthesis retention (2019) | Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis |

| 2 | 78 | F | 28 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; hypertension; history of deep vein thrombus; history of melanoma; history of basal cell cancer | 3 | Initial right TKA (2005); long stem revision rotating hinge TKA (2019); arthrotomy (2023) | Coagulase negative staphylococcus |

| 3 | 59 | M | 42 | Morbid obesity; dyslipidemia; history of alcoholism | 5 | Initial right TKA (2020); arthrotomy (2021); arthrotomy/poly exchange (2021); articulating knee spacer (2021); long stem revision TKA (2021) | Streptococcus mitis; Enterobacter cloacae; Enterococcus faecalis; Coagulase negative staphylococcus |

| 4 | 84 | M | 27 | Stage 3 chronic kidney disease; hypothyroidism; chronic pulmonary disease; carotid stenosis; hypertension; Alzheimer’s disease; sleep apnea | 7 | Initial left TKA (2015); articulating spacer (2016); revision TKA (2017); patellar realignment (2017); second articulating spacer (2017); long stem rotating hinge revision TKA (2018); arthrotomy/poly exchange (2022) | Serratia marcescens |

All had multiple medical comorbidities (Table 1).

All patients had multiple healed anterior knee scars from previous surgeries.

Laboratory results indicated pre-operative infective organisms (Table 1).

Prior to operative intervention, radiography imaging was conducted.

Infected long stem TKA.

Single stage removal of the long stem revision TKA and insertion of cephalomedullary fusion nail.

The patient underwent surgery for removal of her chronically infected long stem revision and insertion of an antibiotic cement spacer and cephalomedullary fusion nail.

Single stage removal of the long stem revision TKA and insertion of cephalomedullary fusion nail.

Single stage removal of the long stem revision TKA and insertion of cephalomedullary fusion nail. He had an 11.5 mm diameter by 70 cm nail placed (Figure 1B). He developed a post operative wound dehiscence that healed without further surgery. He had daily dressing changes for 5 weeks. He received a 6-week course of intravenous antibiotics. He was ambulatory with a walker during his initial hospital stay, and advanced to independent ambulation with Lofstrand forearm crutches and a shoe lift.

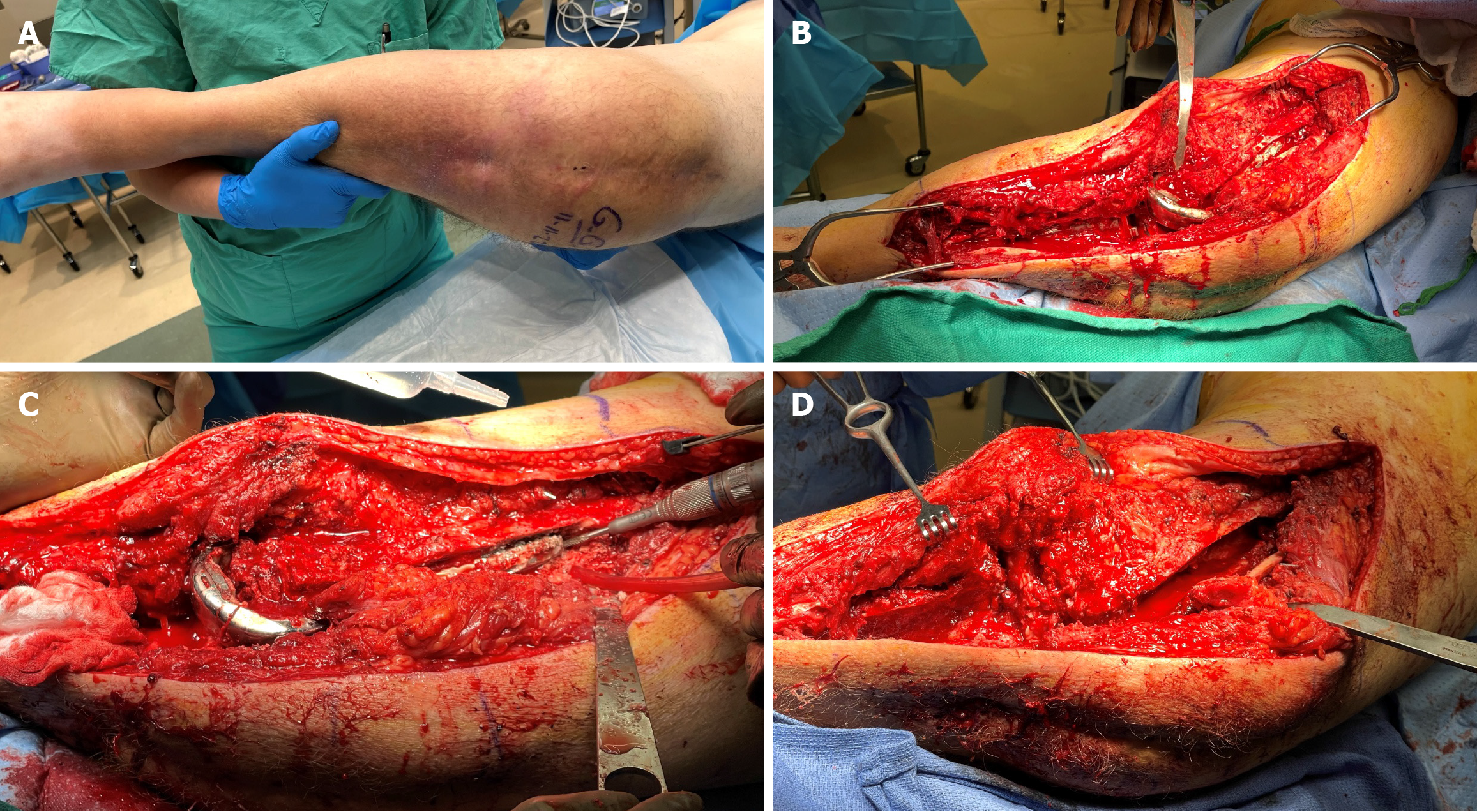

Following general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation, a urinary catheter and radial arterial line were inserted. The patient was placed in the lateral decubitus position on a radiolucent table (Figure 2A). A long lateral incision was made over the femur, knee and tibia, away from the previous anterior incisions. Laterally based osteotomies of the femur and tibia were used to remove the long stems of the infected knee components (Figure 2B-D)[16]. The patellar button and all retained cement were removed. After extensive lavage the wounds were closed and a separate prep, drape, and new surgical set up was employed.

A long cephalomedullary antegrade nail (Smith and Nephew Trigen KF Nail, Memphis, TN, United States) was inserted with C-arm fluoroscopic assistance. The femoral and tibial osteotomies were repaired using 18-gauge stainless steel monofilament cerclage wires around the long fusion nail. The lower extremity was shortened as needed to attempt bone contact between the femur and tibia and to assist with wound closure. Proximal fixation was accomplished with two 6.5 mm cephalomedullary screws. All nails were distally locked with two lateral-to-medial 5.0 mm screws. Two packages (80 g) of manually prepared antibiotic cement containing 6 g of powdered vancomycin and 4.8 g of powdered tobramycin was placed in the bony defects at the knee and metaphyseal areas of the femur and tibia. The wounds were closed over suction drains.

Patient was ambulatory with a walker and shoe lift at his last follow-up visit (28 months).

Patient was ambulatory with a walker and shoe lift at her last follow-up visit (27 months).

Patient was ambulatory with a cane and shoe lift 31 months post KF.

Patient was ambulatory with a crutch and shoe lift. He died 16 months later from unrelated causes.

Patient demographics, operative summary, and outcomes are presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3. There were 3 males and one female. The average age was 73.5 years. Body mass index ranged from 27 kg/m2 to 63 kg/m2. The average number of preoperative surgeries on the affected knee prior the KF procedure was 4.75 (range 3 to 7).

| Case | Operative knee | Pre-op revision implant | Fusion nail diameter (mm)/Length (mm) | Operative time (hours) | Estimated blood loss (mL) | Intra-operative transfusion (mL) |

| 1 | Right | Stryker triathlon revision CCK | 13/700 | 6 | 3600 | 1800 |

| 2 | Right | Biomet rotating hinge OSS | 11.5/700 | 8 | 3500 | 1800 |

| 3 | Right | Biomet vanguard revision SSK | 11.5/800 | 10 | 1500 | 1200 |

| 4 | Left | Biomet rotating hinge OSS | 11.5/700 | 10 | 400 | 300 |

| Case | ICU LOS (days) | Wound complication | Total post-op knee surgeries (n) | Description of subsequent surgeries | Follow-up (months) | Ambulatory at last follow-up |

| 1 | 7 | Wound dehiscence | 1 | Incision and drainage ipsilateral thigh abscess | 28 | Yes, with rolling platform walker and heel lift |

| 2 | 8 | Wound dehiscence | 3 | Incision/drainage leg skin graft substitute; skin graft | 27 | Yes, with walker and shoe lift |

| 3 | 3 | Wound dehiscence | 1 | Skin graft substitute | 31 | Yes, with cane and shoe lift |

| 4 | 1 | Wound dehiscence | 0 | N/A | 16 (deceased) | Yes, with Lofstrum crutch and shoe lift |

The average time in the surgical suite was 8.5 hours, which included the two separate operative procedures and set up time between them. All patients went to the intensive care unit intubated and were extubated the following day. The average blood loss was 2250 mL (400 mL to 3600 mL), and all patients received intraoperative blood transfusions (average 1275 mL, range 300 mL to 3600 mL). They spent an average of 4.75 days in the intensive care unit (range 1 to 8).

All patients experienced some form of wound dehiscence. Three required further surgery. At the time of latest follow-up, all were clinically infection free, off antibiotics, and none had a draining sinus. All were ambulatory with waking aides (walker, crutches, cane) and three used an external shoe lift. All were satisfied with their decision to salvage their lower extremity. No specific patient reported outcome measures were performed. The average follow-up was 25.5 months (range 16 to 31). Three of the patients were alive at the time of this report. One died of causes unrelated to his knee surgery (see illustrative case).

AKA results in inferior clinical results to KF, with many patients unable to walk. Thus, KF should be strongly considered a superior salvage procedure. Better functional results can be expected, including some degree of ambulation. A variety of techniques are available to perform KF, including external fixation, plating, intramedullary nailing, specialized modular nails, and combined modalities in the setting of failed TKA[17]. The complication rates for KF after periprosthetic knee infection can be high[18].

Our series represents a distinct subset of these patients: Those with long stem infected revision prostheses. Unfortunately, surgical treatment options are more limited in this group. External fixation and plating are not possible. Modular fusion nails offer the advantage restoration of limb length and alignment[19-22] but may not provide enough proximal fixation. Long antegrade fusion nails can provide good clinical results[23-25] but can place the patient at risk for peri-implant fracture of the proximal femur if cephalomedullary fixation is not employed[26]. Attempted arthrodesis can be performed in 1 or 2 stages depending on the virulence of the organism, soft tissue envelope, patient factors and surgeon preference. Bone loss at the knee can be filled with allograft, metal spacers or cement[27].

These patients have had previous anterior knee incisions that predispose them to wound problems and the potential need for local or free flap coverage. The senior author chose a lateral approach to intentionally avoid the anterior soft tissues, along with shortening as needed to allow for wound closure and bony contact between the femur and tibia. Although all had some level of post operative wound dehiscence, no patient required flap coverage, and all eventually healed. Three of the four patients had a limb length discrepancy and required an external shoe lift. Makhdom et al[27] used a similar technique employing an antibiotic coated cephalomedullary nail.

This case report has several limitations. It is a small clinical case series, and as such it may not be applicable to patients in other settings. No patient reported outcome measures were performed. The follow-up was relatively short, and it is possible that the 3 surviving patients may develop late infection with longer follow-up[28]. The knee was not studied with advanced imaging like a metal reducing computerized tomography scan to assess bony fusion. The antibiotic cement block around the nail likely functioned as an artificial functional fusion[27]. The three survivors could develop implant loosening with longer follow-up. Many patients may not be able to tolerate such an extensive surgery and surgeons may opt for an amputation instead of such a complex reconstruction.

In summary KF should be strongly considered in the treatment of an infected long stem revision TKA that has failed previous two stage re-implantation. Only long cephalomedullary nails offer satisfactory stability after implant removal and protection of the proximal femur in this setting. This is a complex reconstruction with many potential complications, including death. However, if successful, patients can expect to walk with assistive devices and shoe lift due to limb shortening. Post operative wound problems and secondary surgeries for wound coverage are common. Late infection is possible and could result in subsequent AKA or hip disarticulation or mortality[6].

The authors would like to thank Sundaye Moore, for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

| 1. | Goldman AH, Clark NJ, Taunton MJ, Lewallen DG, Berry DJ, Abdel MP. Definitive Resection Arthroplasty of the Knee: A Surprisingly Viable Treatment to Manage Intractable Infection in Selected Patients. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:855-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Carr JB 2nd, Werner BC, Browne JA. Trends and Outcomes in the Treatment of Failed Septic Total Knee Arthroplasty: Comparing Arthrodesis and Above-Knee Amputation. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1574-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Edgar MC, Alderman RJ, Scharf IM, Jiang SH, Davison-Kerwood M, Zabawa L. A comparison of outcomes for above-knee-amputation and arthrodesis for the chronically infected total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2023;33:2933-2941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hoveidaei AH, Ghaseminejad-Raeini A, Esmaeili S, Movahedinia M, Karbasi S, Khonji MS, Nwankwo BO, Shrestha A, Conway JD. Knee fusion versus above knee amputation as two options to deal with knee periprosthetic joint infection. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2024;144:5229-5238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hungerer S, Kiechle M, von Rüden C, Militz M, Beitzel K, Morgenstern M. Knee arthrodesis versus above-the-knee amputation after septic failure of revision total knee arthroplasty: comparison of functional outcome and complication rates. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Knee Fusion or Above-The-Knee Amputation after Failed Two-Stage Reimplantation Total Knee Arthroplasty. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2015;3:241-243. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Abouei M, Elhessy AH, Conway JD. Functional Outcome of Above-Knee Amputation After Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2023;22:101149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fedorka CJ, Chen AF, McGarry WM, Parvizi J, Klatt BA. Functional ability after above-the-knee amputation for infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1024-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hantouly AT, Lawand J, Alzobi O, Hoveidaei AH, Salman LA, Hameed S, Ahmed G, Citak M. High mortality rate and restricted mobility in above knee amputation following periprosthetic joint infection after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2024;144:5273-5282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Juryn MS, Ekhtiari S, Wolfstadt JI, Backstein DJ. Above-Knee Amputation Following Chronically Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty: Patient-Reported Satisfaction and Functional Outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2025;40:486-493.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Orfanos AV, Michael RJ, Keeney BJ, Moschetti WE. Patient-reported outcomes after above-knee amputation for prosthetic joint infection. Knee. 2020;27:1101-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aparicio G, Otero J, Bru S. High Rate of Fusion but High Complication Rate After Knee Arthrodesis for Infected Revision Total Knee Replacement. Indian J Orthop. 2020;54:616-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schwarzkopf R, Kahn TL, Succar J, Ready JE. Success of different knee arthrodesis techniques after failed total knee arthroplasty: is there a preferred technique? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:982-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen AF, Kinback NC, Heyl AE, McClain EJ, Klatt BA. Better function for fusions versus above-the-knee amputations for recurrent periprosthetic knee infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2737-2745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yeung CM, Lichstein PM, Varady NH, Maguire JH, Chen AF, Estok DM 2nd. Knee Arthrodesis Is a Durable Option for the Salvage of Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:3261-3268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pasquier GJM, Huten D, Common H, Migaud H, Putman S. Extraction of total knee arthroplasty intramedullary stem extensions. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2020;106:S135-S147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | MacDonald JH, Agarwal S, Lorei MP, Johanson NA, Freiberg AA. Knee arthrodesis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:154-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mercurio M, Gasparini G, Cofano E, Zappia A, Familiari F, Galasso O. Knee Arthrodesis for Periprosthetic Knee Infection: Fusion Rate, Complications, and Limb Salvage-A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12:804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stavrakis AI, Mayer EN, Devana SK, Chowdhry M, Dipane MV, McPherson EJ. Outcomes of Modular Knee Arthrodesis for Challenging Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Arthroplast Today. 2022;13:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Coden G, Bartashevskyy M, Berliner Z, Niu R, Freccero D, Bono J, Abdeen A, Smith EL. Modular Knee Arthrodesis as Definitive Treatment for Periprosthetic Infection, Bone Loss, and Failure of the Extensor Mechanism After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2024;25:101261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gallusser N, Goetti P, Luyet A, Borens O. Knee arthrodesis with modular nail after failed TKA due to infection. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25:1307-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Namdari S, Milby AH, Garino JP. Limb salvage after infected knee arthroplasty with bone loss and extensor mechanism deficiency using a modular segmental replacement system. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:977.e1-977.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brown NM, Balkissoon R, Saltzman BM, Haughom B, Li J, Levine B, Sporer S. Knee Arthrodesis With an Intramedullary Antegrade Rod as a Salvage Procedure for the Chronically Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4:e20.00082-e20.00086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bargiotas K, Wohlrab D, Sewecke JJ, Lavinge G, DeMeo PJ, Sotereanos NG. Arthrodesis of the knee with a long intramedullary nail following the failure of a total knee arthroplasty as the result of infection. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89 Suppl 2 Pt.1:103-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Razii N, Abbas AM, Kakar R, Agarwal S, Morgan-Jones R. Knee arthrodesis with a long intramedullary nail as limb salvage for complex periprosthetic infections. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26:907-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Panagiotopoulos E, Kouzelis A, Matzaroglou Ch, Saridis A, Lambiris E. Intramedullary knee arthrodesis as a salvage procedure after failed total knee replacement. Int Orthop. 2006;30:545-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Makhdom AM, Fragomen A, Rozbruch SR. Knee Arthrodesis After Failed Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:650-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Balato G, Rizzo M, Ascione T, Smeraglia F, Mariconda M. Re-infection rates and clinical outcomes following arthrodesis with intramedullary nail and external fixator for infected knee prosthesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/