Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110530

Revised: July 9, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 192 Days and 0.4 Hours

Low back pain is a major cause of disability worldwide, with intervertebral disc degeneration contributing to nearly 40% of cases. Conventional treatments focus on symptom relief without addressing the underlying degeneration. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), a regenerative therapy rich in growth factors, offers potential the

To evaluate the efficacy of intradiscal autologous PRP injection in reducing pain and improving function in patients with chronic lumbar disc prolapse.

This pilot quasi-experimental study was conducted in tertiary care centre between July 2022 and June 2024. The study involved comparing the outcomes between group A (n = 17) who failed to respond to conservative treatment measures and received intradiscal PRP injection with group B (n = 22) who responded to conservative treatment. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and Functional Rating Index (FRI) scores were recorded at baseline, 3 weeks, and 6 weeks for both the groups.

Forty patients were enrolled in the study. The PRP group demonstrated significant improvement in VAS and FRI scores compared to baseline. While both groups improved from their respective baselines, direct between-group comparisons are limited by baseline differences in symptom severity. Patients who failed conservative trial showed significant improvement following PRP intervention, with outcomes approaching those observed in physiotherapy responders.

Intradiscal PRP injection significantly improved pain and function in patients with lumbar disc disease, with clinical improvements that approached the level observed in physiotherapy responders, despite baseline differences in symptom severity. PRP shows promise as an effective treatment for lumbar disc pathology; however, these preliminary findings are limited by the small sample size and short follow-up, warranting larger trials with long-term evaluation.

Core Tip: Intradiscal autologous platelet-rich plasma injection significantly reduced pain and improved function in chronic lumbar disc prolapse patients unresponsive to physiotherapy, achieving outcomes comparable to physiotherapy responders at 3 and 6 weeks. While these preliminary findings are encouraging, the brief 6-week follow-up period precludes assessment of durability, and larger studies with extended follow-up are essential to establish long-term efficacy, evaluate potential structural effects and safety.

- Citation: Mounisamy P, Dwajan A, Sahoo D, Jeyaraman N, Muthu S, Ramasubramanian S, Jeyaraman M. Efficacy of intradiscal autologous platelet-rich plasma injection in chronic lumbar disc prolapse: A quasi-experimental study. World J Orthop 2025; 16(12): 110530

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i12/110530.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110530

Low back pain (LBP) is currently recognized as the leading cause of physical disability worldwide[1]. In 2020, there were over 500 million cases of LBP globally, and this number is expected to rise to more than 800 million by 2050[2]. Among the various etiologies of LBP, intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration stands out as a predominant cause, contributing to nearly 40% of cases[3,4]. IVD degeneration not only results in chronic pain but also imposes a substantial burden of disability and financial costs on individuals and healthcare systems alike[5,6]. Beyond the physical manifestations, LBP secondary to disc degeneration is associated with profound psychological and social distress, further complicating the overall health and quality of life of affected individuals. IVD degeneration involves progressive loss of extracellular matrix components (proteoglycans, collagen) mediated by increased enzymatic activity (metalloproteinases, caspases, aggrecanases) and fibronectin fragment accumulation. The loss of proteoglycans, which play a crucial role in maintaining the osmotic pressure of the disc, leads to diminished hydration capacity under stress. Consequently, the IVDs lose fluid and height, a process that contributes to disc bulging and the potential for disc protrusion, extrusion, and sequestration[4,7,8]. Moreover, the loss of aggrecan, a critical proteoglycan in the disc matrix, has been shown to reduce the suppression of neuronal ingrowth, thereby exacerbating discogenic pain. Current therapeutic approaches for managing IVD degeneration and its associated LBP are predominantly palliative, focusing on symptom relief rather than addressing the underlying degeneration. These strategies include spinal surgery, anti-inflammatory medications, and physiotherapy[9]. However, such interventions do not restore the damaged disc and may inadvertently accelerate the degeneration of adjacent discs, leading to a perpetuation of the degenerative cycle. This limitation underscores the need for regenerative treatment modalities that can both alleviate symptoms and promote disc repair[10,11].

The advent of regenerative medicine has introduced novel therapeutic avenues, among which the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has garnered significant attention. PRP is rich in growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor beta-1, basic-fibroblast growth factor, and epidermal growth factor, all of which play pivotal roles in promoting cellular proliferation and tissue regeneration[12,13]. Given the IVD's inherently low vascularity and limited regenerative capacity, the potential of intradiscal PRP injections to potentially influence disc pathophysiology is particularly compelling, though structural regeneration remains unproven without imaging confirmation. However, despite the theoretical benefits, clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of PRP in the treatment of IVD degeneration remains sparse. The majority of studies to date consist of case series or prospective trials, with a paucity of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that could provide robust evidence for its efficacy. The existing literature on the use of PRP for disc-related pathologies is largely limited without comparative treatment arms[14-18]. Additionally, while some studies have reported improvements in pain and functional outcomes following PRP treatment, the heterogeneity in study designs, outcome measures, and follow-up durations complicates the interpretation of results. Therefore, there is a critical need for well-designed RCTs to elucidate the therapeutic potential of PRP in this context and to establish standardized protocols for its use.

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of intra-discal autologous PRP injection in reducing LBP and improving functional outcomes in participants with lumbar disc disease as measured by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and Functional Rating Index (FRI) scores.

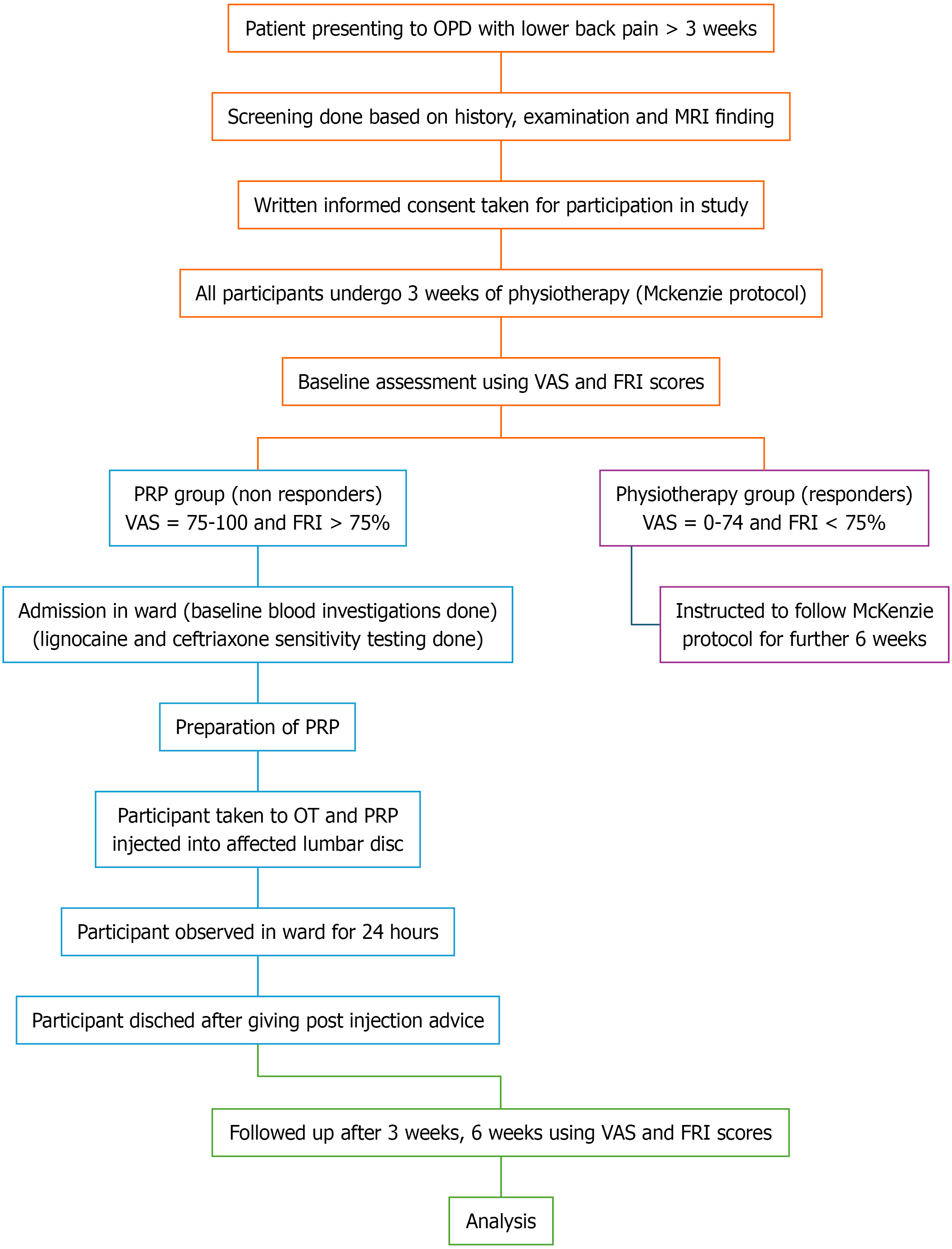

The study was conducted in Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), a tertiary care center in Puducherry, India between July 2022 and June 2024 after approval from the JIPMER Institutional Ethics Committee with approval document JIP/IEC/2022/072 dated 10 October, 2022. The study was a longitudinal, quantitative, quasi-experimental pilot study with a non-equivalent control group design with a convenient sampling method. The flowchart of the methodology of the study is depicted in Figure 1.

The study included two groups: Group A and group B. Group A included patients presenting with single level lumbar disc disease who were classified as non-responders to 3 weeks of physiotherapy by McKenzie protocol. They underwent intradiscal autologous PRP injection in the involved disc. Group B consists of patients with lumbar disc disease who were classified as responders to 3 weeks of physiotherapy by McKenzie protocol. They were instructed to continue physiotherapy until 6 weeks.

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged between 18 to 50 years with single level lumbar disc disease in stages of protrusion or extrusion that corresponds to the clinical findings noted in the patient with maintained IVD height of at least 50% of the adjacent level on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Exclusion criteria: Patients with spinal dysmorphism, neurological deficit, sequestered disc fragments, previous surgical intervention for spine, facet arthropathy, sacroiliac joint pain, and traumatic spine injury; patients with known bleeding disorder or on anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs; pregnant women; patients with psychiatric illness; patients with peripheral neuropathy due to diabetes, leprosy, syphilis; patients with malignant disorders; patients with infective discitis and systemic infections like human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C were excluded from the study.

All the selected participants were instructed to undergo 3 weeks of physiotherapy based on McKenzie back protocol[19]. This protocol consisted of a series of back and core strengthening exercises which were performed sequentially in a controlled manner. The exercises were demonstrated and taught to the participants by the investigator and further instructions were given to continue the same at home on a twice-daily basis- in the morning and evening. The approximate time taken to complete all the exercises in sequence was 40 minutes. The participants were contacted via phone call weekly to ensure their adherence to the regimen.

The participants were assessed using VAS and FRI scores after 3 weeks of physiotherapy and grouped as responders or non-responders. PRP group: Non-responders to physiotherapy with VAS score ≥ 75 mm and FRI score ≥ 75%; Physiotherapy group: Responders to physiotherapy with VAS < 75 mm and FRI score < 75%. The VAS and FRI were self-administered by each participant and the scores were calculated and recorded by the investigator serially at baseline, 3 and 6 weeks.

The physiotherapy responder group was selected as a pragmatic comparator to assess whether PRP could offer meaningful improvement in patients who had failed conservative care. This design reflects real-world clinical decision-making, where non-responders are typically escalated to more invasive options. Using physiotherapy responders as a benchmark allowed us to evaluate the potential of PRP as a non-surgical alternative. While not equivalent at baseline, this grouping was ethically and clinically appropriate for a pilot quasi-experimental framework.

With the help of the differential centrifugation method, autologous PRP was prepared[20]. About 1.4 mL of acid citrate dextrose adenine was added to 2 sterile conical bottom centrifugation tubes of 15 mL capacity (Tarsons® SpinwinTM, India). A total of 20 mL of whole blood was drawn from the antecubital vein using a 16G butterfly needle and deposited in 2 conical tubes and subjected to 1st centrifugation at a rate of 1100 rpm for 15 minutes. The plasma was transferred to another sterile conical tube using an 18G spinal needle under a biosafety cabinet, which was further subjected to 2nd centrifugation at a rate of 3100 rpm for 20 minutes. A total of 2 mL of PRP was isolated and transported to the operation theatre (OT).

In OT, under strict aseptic precautions, the participant was positioned prone with a pillow placed under the abdomen to reduce lumbar lordosis. A fluoroscope was employed to visualize the landmarks for needle insertion. Following cleaning and draping, 5 mL 2% lignocaine is infiltrated along the needle track. The fluoroscope was angulated cranio-caudally to align the vertebral endplates parallel at the level of interest.

The fluoroscope was rotated ipsilateral oblique in a mediolateral direction depending on the side of percutaneous access (toward the right on the patient’s right side and the left on the patient’s left side). A Tuohy needle (18G) was inserted 5 cm away from the midline with an angulation of 15-20 degrees directed toward the disc, using the Kambian triangle as a reference[21].

The endpoint of needle insertion was defined as the center of the disc, which was verified with C-arm imaging using both anteroposterior and lateral views (Figure 2). The PRP was transferred to a 5 mL syringe connected to the Tuohy needle and injected into the disc until increased resistance was felt in the plunger and the solution could no longer be easily injected. Sterile dressing was applied and the participant was shifted to a supine position.

The participants were observed for 15 minutes in the recovery room for any adverse reaction, after which they were shifted back to the ward. In-patient bed rest was advised for 24 hours. The participants were advised bed rest along with tablet paracetamol 500 mg thrice daily for 3 days then as needed. Patients were instructed to avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, and any other analgesics or medications that might affect platelet function. Strict instructions were given to avoid lifting heavy weights or squatting or forward bending, and travel by two- or four-wheeled vehicles for 3 months after injection. The participant resumed work and other activities as tolerated, with instructions to avoid engaging in activities that exacerbated the pain. The participants were followed up at 3 weeks and 6 weeks post-injection and were assessed by VAS and FRI scores.

The participants were instructed to continue the Mckenzie protocol for another 6 weeks. The participants were contacted weekly via telephone to check adherence to the same. The assessment was done using VAS and FRI scores at 3 weeks and 6 weeks on an outpatient basis. The participant resumed work and other activities as tolerated, with instructions to avoid engaging in activities that exacerbated the pain.

All categorical variables such as gender, occupation, level of disc prolapse, and type of disc prolapse were expressed as frequency/percentages. All continuous variables such as age, platelet count, the volume of PRP obtained, the volume of PRP injected, VAS, and FRI scores at baseline, after 3 weeks and 6 weeks were expressed as mean and SD. The distribution of data was explored using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The comparison of categorical variables like gender, occupation, and level of disc prolapse between the groups was done using the χ2/Fisher exact test. To compare the longitudinal changes in clinical outcomes between groups, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed. The within-subject factor was time (baseline, 3 weeks, and 6 weeks), and the between-subject factor was treatment group (PRP vs physiotherapy). The dependent variables analyzed were the VAS and FRI scores. The interaction effect (group × time) was evaluated to determine whether the pattern of change over time differed significantly between groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Additional comparisons of change scores between groups were assessed using independent t-tests. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d for within-group changes, partial η² for repeated measures ANOVA) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were calculated to quantify the magnitude and precision of observed effects. The data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 26.0 (IBM Corp, Chicago, IL, United States). With an alpha error assumed at 5%, a P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Given baseline imbalances, we performed additional baseline-adjusted analyses using ANCOVA to control for initial symptom severity when comparing between-group outcomes.

After screening for eligibility, 40 participants were recruited for the study. Eighteen participants were assigned to the PRP group and 22 participants were assigned to the physiotherapy group based on their response to conservative regimen. A participant in the PRP group developed a vasovagal reaction during the procedure. Therefore, the procedure was abandoned and the participant was managed appropriately. This participant was excluded from the analysis. The remaining 39 participants (17 in the PRP group and 22 in the physiotherapy group) were followed up for 6 weeks with no patients lost to follow-up.

The demographic characteristics of age, gender, and occupation were similar between the PRP and the physiotherapy groups, with no statistically significant differences observed, as shown in Table 1. The clinical parameters of the levels and location of disc prolapse were similar between the two groups, with no significant differences observed, as shown in Table 1.

| Demographic characteristics | PRP group (n = 17) | Physiotherapy group (n = 22) | P value | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 28.9 ± 8.6 | 31.8 ± 7.8 | 0.271 | |

| Sex | Male | 16 (94.1) | 19 (86.4) | 0.422 |

| Female | 1 (5.9) | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Occupation | Labourer | 6 (35.3) | 4 (18.2) | 0.462 |

| Farmer | 2 (11.8) | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Factory worker | 2 (11.8) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Student | 3 (17.6) | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Others | 4 (23.5) | 11 (50) | ||

| Level of disc disease | L3-L4 | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.3852 |

| L4-L5 | 6 (35.3) | 11 (50.0) | ||

| L5-S1 | 10 (58.8) | 11 (50.0) | ||

| Location of disc herniation | Left paracentral | 4 (23.5) | 3 (13.6) | 0.6012 |

| Posterocentral | 9 (52.9) | 15 (68.2) | ||

| Right paracentral | 4 (23.5) | 4 (18.2) | ||

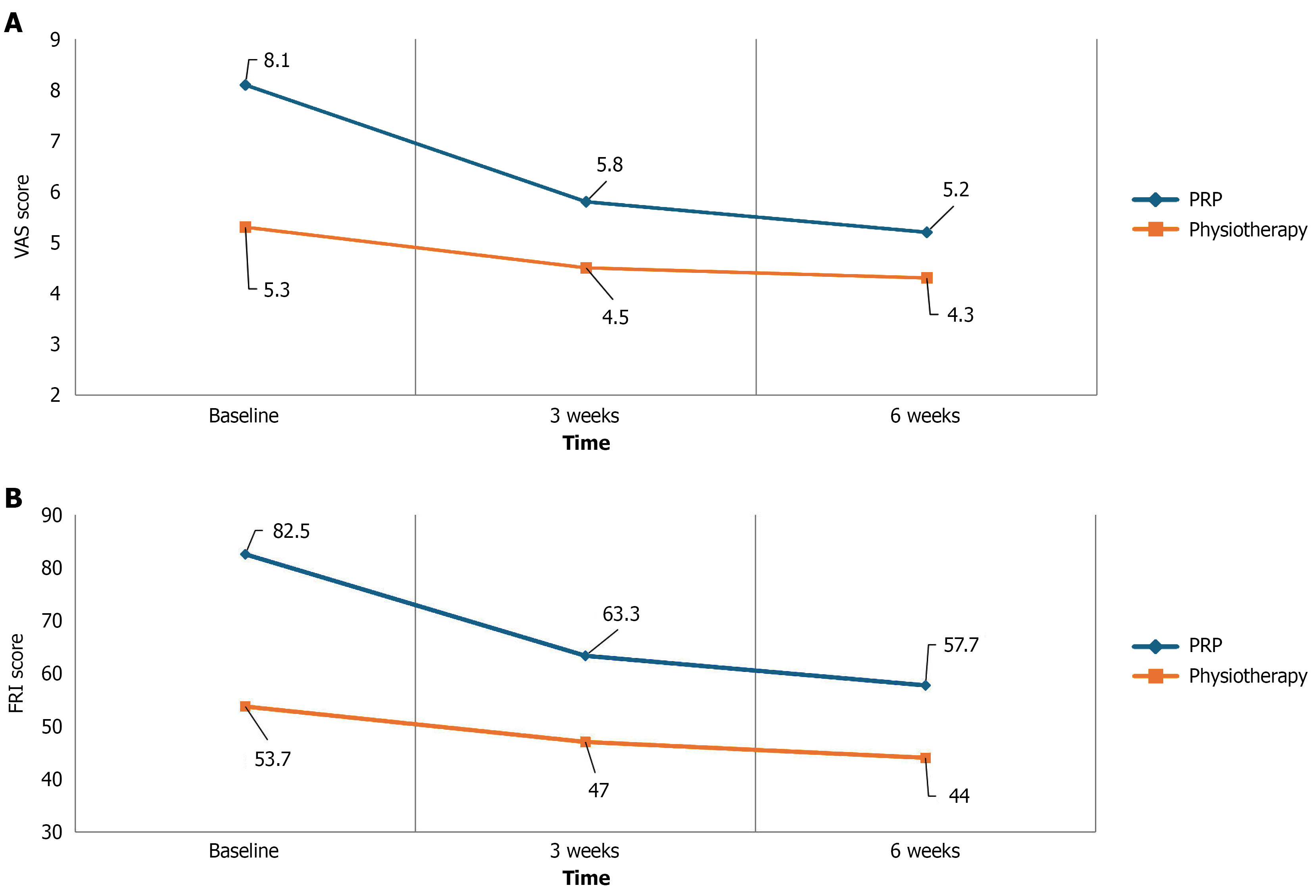

The PRP group showed a greater reduction in VAS scores over time compared to the physiotherapy group as shown in Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 3A. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a significant group × time interaction (P < 0.05), indicating a differing pattern of improvement between groups. Pairwise comparisons confirmed statistically significant reductions in VAS from baseline to both 3 and 6 weeks in the PRP group as shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Descriptive statistics | Group | Mean | SD |

| VAS baseline | PRP (n = 17) | 8.171 | 0.6622 |

| Physiotherapy (n = 22) | 5.355 | 1.5668 | |

| Total (n = 39) | 6.582 | 1.8822 | |

| VAS week-3 | PRP (n = 17) | 5.847 | 1.8101 |

| Physiotherapy (n = 22) | 4.550 | 2.1456 | |

| Total (n = 39) | 5.115 | 2.0852 | |

| VAS week-6 | PRP (n = 17) | 5.224 | 1.9273 |

| Physiotherapy (n = 22) | 4.323 | 1.9859 | |

| Total (n = 39) | 4.715 | 1.9870 |

| Time (I) | Time (J) | Mean difference (I-J) | SE | Sig.1 (P value) | 95%CI for difference1 | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Baseline | 3 weeks | 1.564a | 0.256 | < 0.05 | 0.922 | 2.206 |

| 6 weeks | 1.989a | 0.247 | < 0.05 | 1.371 | 2.608 | |

| 3 weeks | Baseline | -1.564a | 0.256 | < 0.05 | -2.206 | -0.922 |

| 6 weeks | 0.425 | 0.188 | 0.089 | -0.047 | 0.897 | |

| 6 weeks | Baseline | -1.989a | 0.247 | < 0.05 | -2.608 | -1.371 |

| 3 weeks | -0.425 | 0.188 | 0.089 | -0.897 | 0.047 | |

FRI scores improved significantly over time in the PRP group compared to the physiotherapy group, with a significant Group × Time interaction on repeated measures ANOVA (P < 0.05; Tables 4 and 5; Figure 3B).

| Descriptive statistics | Group | Mean | SD |

| FRI baseline | PRP (n = 17) | 82.500 | 6.6144 |

| Physiotherapy (n = 22) | 53.750 | 16.3436 | |

| Total (n = 39) | 66.282 | 19.3553 | |

| FRI week-3 | PRP (n = 17) | 63.3824 | 17.27401 |

| Physiotherapy (n = 22) | 47.0455 | 17.36575 | |

| Total (n = 39) | 54.1667 | 18.96442 | |

| FRI week-6 | PRP (n = 17) | 57.7941 | 16.90697 |

| Physiotherapy (n = 22) | 44.0909 | 20.00812 | |

| Total (n = 39) | 50.0641 | 19.72248 |

| Time (I) | Time (J) | Mean difference (I-J) | SE | Sig.1 (P value) | 95%CI for difference1 | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Baseline | 3 weeks | 12.911a | 2.294 | < 0.05 | 7.159 | 18.663 |

| 6 weeks | 17.182a | 2.697 | < 0.05 | 10.418 | 23.947 | |

| 3 weeks | Baseline | -12.911a | 2.294 | < 0.05 | -18.663 | -7.159 |

| 6 weeks | 4.271a | 1.433 | < 0.05 | 0.678 | 7.865 | |

| 6 weeks | Baseline | -17.182a | 2.697 | < 0.05 | -23.947 | -10.418 |

| 3 weeks | -4.271a | 1.433 | < 0.05 | -7.865 | -0.678 | |

The PRP group showed significantly greater reductions in VAS and FRI scores compared to the physiotherapy group at both 3 and 6 weeks, as confirmed by independent t-tests (P < 0.05; Table 6). We acknowledge this allocation method resulted in significant baseline differences between groups (PRP group: VAS = 8.2 ± 0.7, FRI = 82.5 ± 6.6; physiotherapy group: VAS = 5.4 ± 1.6, FRI = 53.8 ± 16.3). Therefore, our primary analysis focuses on within-group changes over time rather than direct between-group comparisons.

| Outcome | 3 weeks | 6 weeks | ||

| Value | P value | Value | P value | |

| PRP group (n = 17) | ||||

| VAS score | 2.32 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 | 2.94 ± 1.5 | 0.02 |

| FRI score | 19.11 ± 17.1 | < 0.001 | 24.70 ± 15.5 | 0.004 |

| Physiotherapy group (n = 22) | ||||

| VAS score | 0.81 ± 1.4 | < 0.001 | 1.03 ± 1.4 | 0.012 |

| FRI score | 6.70 ± 11.5 | < 0.01 | 9.66 ± 17.5 | 0.017 |

The mean volume of PRP obtained per patient was 3.70 ± 0.4 mL, of which an average of 2.5 ± 0.56 mL was injected into the affected disc. The mean baseline platelet count was 2.9 × 105/μL of whole blood. Platelet concentration in the PRP samples ranged from 5 × 105/μL to 10 × 105/μL, representing an approximate 2.5- to 4-fold increase over baseline levels. 105/μL, corresponding to 2.5 to 4 times the baseline whole blood platelet count.

One patient in the PRP group experienced a vasovagal episode during the procedure, which was promptly managed with procedure discontinuation. No cases of discitis, infection, or neurological complications were observed during the 6-week follow-up period.

Effect sizes for the PRP group were substantial (Cohen's d = 1.8 for VAS improvement, d = 1.4 for FRI improvement at 6 weeks), though confidence intervals remain wide due to the small sample size (95%CI for VAS change: 1.2-3.7 points; 95%CI for FRI change: 16.8-32.6 points).

The most frequent cause of adult LBP is degenerative disc disease. Genetic, mechanical, environmental factors and senescence can contribute to this disorder. IVDs help transmit loads by absorbing compressive pressures due to their unique structure. The extracellular matrix is usually lost during degeneration, and pro-inflammatory factors are elevated. Chronic discogenic pain is caused by endplate calcification, which decreases permeability, inhibits nutrition transfer into the disc, and increases strain on nearby joints. Treatments often begin with conservative therapy and may progress to surgical interventions if necessary. The IVD has limited regenerative potential due to its avascular nature. In recent years, there has been a surge in the use of PRP in the treatment of orthopaedic disorders. Platelets, which are a major component of PRP, are extracted from autologous whole blood and release growth factors that aid in tissue creation and repair by regulating cell proliferation and promoting differentiation, stimulating angiogenesis, and facilitating the synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins. The literature indicates that it is more effective at reducing pain and improving mobility than conventional physical therapy for treating musculoskeletal conditions including but not limited to adhesive capsulitis and tendinopathies[22,23]. In comparison, relatively little research has been done to determine the effectiveness of PRP in lumbar disc herniation (LDH). To the best of our knowledge, no study has compared the therapeutic effects of PRP with physiotherapy in individuals presenting with symptomatic LDH. This research sought to bridge this gap in the current understanding.

In the present study, the mean age of the study population was 30.1 years which was comparable to the study done by Akeda et al[24] (33.8 years) and Jain et al[25] (34.75 years). In the present study, the majority of the participants recruited were males (89.7%) which was in contrast to studies done by Zhang et al[13], Tuakli-Wosornu et al[26], Levi et al[27], and Ruiz-Lopez and Tsai[28] where more female patients had symptomatic LDH. L4-L5 (43.6%) and L5-S1(53.8%) were the most common levels involved in the present study which was in line with previous research[13,25,27,29-31]. Paracentral involvement was seen in 15 (38.5%) participants and posterocentral in 24 (61.5%) participants. This is in contrast to a study done by Wongjarupong et al[32] where the paracentral type of disc involvement was most commonly seen.

The average volume of PRP injected in a single disc was 1.8 mL with an SD of 0.4 mL which was marginally more as compared to previous clinical trials[24,26,27,33]. The results demonstrated that intradiscal PRP injection and physiotherapy both reduced pain and improved functional outcomes in patients with symptomatic LDH but the magnitude of improvement was more in the PRP group. Specifically, the PRP group showed a mean decrease in VAS scores of 2.32 points after 3 weeks and 2.94 points after 6 weeks, and a mean decrease in FRI scores of 19.11 points after 3 weeks and 24.70 points after 6 weeks. The physiotherapy group showed significantly smaller improvements, with a mean decrease in VAS scores of 0.81 points after 3 weeks and 1.03 points after 6 weeks, and a mean decrease in FRI scores of 6.70 points after 3 weeks and 9.66 points after 6 weeks.

In 2017, Akeda et al[24] published a clinical trial including six patients who had chronic LBP. After lumbar discs were identified using MRI and provocative discography, 2.0 mL of PRP serum was injected into the nucleus pulposus. Over six months, they saw a considerable reduction in pain with no adverse effects[24]. Thirty-five individuals received 47 intradiscal PRP injections in the thoracic and lumbar disc from Bodor et al[29] in 2014. Two-thirds of the patients showed a substantial decline in their Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) ratings. PRP was injected into the nucleus pulposus of degenerative discs seen on discography by Navani and Hames[33] in 2015, who recruited six patients with persistent discogenic LBP. Verbal Pain Scores and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) both showed improvements over 24 weeks, with no negative side effects[33].

In 2016, Levi et al[27] found a 50% reduction in VAS scores and a 30% reduction in VAS and ODI scores at 6 months in 47% of participants treated with intradiscal PRP. The present study aligns with these results, demonstrating significant pain and disability reductions in the PRP group. A RCT was conducted by Tuakli-Wosornu et al[26] in 2016 to evaluate the use of intradiscal PRP treatment in patients with chronic LBP. Pain, disability, and physical function scores were all significantly improved in the PRP group. This improvement was evident after 1 week and was sustained till at least 8 weeks post-procedure. No adverse effects were noted[26].

A preliminary investigation with 10 patients suffering from persistent lumbar disc prolapse was carried out by Bhatia and Chopra[34] in 2016. After injecting 5 milliliters of autologous PRP close to the affected nerve root, they saw a gradual improvement in symptoms that persisted for at least 12 weeks after the procedure[34]. These results were further consolidated by the results of a randomized control trial done by Ruiz-Lopez and Tsai[28] in 2020 who demonstrated that epidural injections of autologous PRP were found to be superior to steroids in reducing back pain and improving functional outcomes in patients with LDH[28]. Similar studies conducted earlier demonstrated the effectiveness of PRP in improving pain and disability scores[13,31,35].

In a prospective trial done in 2017, Akeda et al[24] recruited fourteen patients who had symptomatic LDH. They reported a 71% pain reduction within one month and significant disability score reductions in 79% of patients treated with PRP. The use of PRP releasate was a highlighting feature of this study[24]. In a 2019 study, Cheng et al[36] assessed the long-term effects of intradiscal PRP injections in 29 individuals who had symptomatic LDH. They saw considerable improvements in both pain [Nutritional Risk Score (NRS)] and function (FRI score and SF-36 scale) for 5-9 years post-procedure[36]. Jain et al[25] in 2020 reported a prospective clinical trial linking improvements in LBP and functional outcomes to platelet concentration in PRP injections, demonstrating a favorable correlation between reductions in NRS and ODI scores and the number of platelets in the PRP sample at 3 months and 6 months[25]. In our study, platelet concentration was measured in each PRP preparation, ranging from 5 × 105/μL to 10 × 105/μL (approximately 2.5 to 4 times baseline). The clinical improvements observed in pain and function are consistent with the findings of Jain et al[25], supporting the relevance of adequate platelet dosing in therapeutic response.

The therapeutic value of PRP for LBP was the subject of a systematic review by Machado et al[16] in 2023. They discovered that PRP treatment for the lumbar spine has a well-established safety profile with a low frequency of adverse events, and is typically supported by level II data[16]. Our findings are supported by the review article published by Guerrero-Molina et al[37] in 2023, which summarizes the growing clinical evidence for PRP in the treatment of LDH and highlights its potential as a minimally invasive alternative for discogenic pain management.

Regarding the safety profile, injections of autologous PRP in the spine have resulted in minimal complications. Zhang et al[13] reported that a participant developed infective discitis post-procedure. Bodor et al[29] reported vasovagal episodes in two patients during the procedure but no adverse effects were noted due to PRP itself. The alignment of this study's results with the existing body of research further supports the effectiveness and safety of intradiscal PRP injections in the management of LDH. These results indicate that PRP injections may be a promising treatment option, offering a more effective alternative to traditional physiotherapy. This could potentially lead to faster recovery times and improved quality of life for patients.

The study has limitations to acknowledge. This study was limited by a small sample size. A larger sample size would have strengthened the results obtained. The follow-up period in this study was only 6 weeks. To determine the effectiveness of intradiscal injections of autologous PRP, a longer follow-up period would have been more appropriate.

The use of physiotherapy responders as a comparison group introduces inherent selection bias, as the baseline characteristics, including pain severity and response trajectory, differ from those of PRP candidates. This must be taken into account when interpreting the comparability of outcomes across groups. While significant baseline differences existed in pain and disability scores between the two groups due to the nature of group allocation, the primary aim was to evaluate the trajectory of clinical improvement within each group and assess whether PRP-treated non-responders could achieve outcomes similar to physiotherapy responders over time. Nonetheless, this inherent baseline difference limits direct group comparability and should be considered when interpreting the results.

Although provocative discography has historically been used to detect discogenic pain, we chose not to employ it in this study due to its invasive nature and potential risks, including discitis, acceleration of disc degeneration, and the provocation of new or worsened pain. Instead, we adopted a stringent diagnostic approach that combined clinical features, MRI findings and physiotherapy response. Our institutional ethics committee approved this strategy, con

One key limitation of this study is the absence of follow-up MRI, which could have provided insights into structural disc changes. Given the short 6-week follow-up, ethical constraints, and limited resources, imaging was deferred. Further, Given the small sample size, the study was not powered to detect small differences; therefore, effect sizes and confidence intervals were emphasized to convey the clinical magnitude and precision of the findings. Future studies should include long-term MRI follow-up to correlate clinical outcomes with disc regeneration.

Future research should focus on larger, multicentric RCTs with longer follow-up periods to confirm the long-term efficacy and safety of intradiscal autologous PRP injections. The studies should include long term MRI follow-up and biochemical outcome measures to establish the durability, safety, and broader applicability of this treatment approach. Additionally, studies exploring the underlying mechanisms of PRP in promoting disc healing and regeneration would be valuable. It would also be beneficial to compare PRP injections with other emerging treatments for LDH to determine the most effective therapeutic approaches.

The findings from the current study suggest intradiscal autologous PRP injection demonstrated early clinical improvement in pain and function among patients with lumbar disc prolapse who failed to respond to physiotherapy achieving outcomes comparable to those of physiotherapy responders at 6 weeks. However, these findings represent early clinical responses only and should be interpreted as preliminary evidence requiring validation through longer-term studies to assess durability of benefits. Longer-term studies are necessary to confirm sustained benefits and evaluate structural regenerative effects.

| 1. | Wu A, March L, Zheng X, Huang J, Wang X, Zhao J, Blyth FM, Smith E, Buchbinder R, Hoy D. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 923] [Article Influence: 153.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990-2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5:e316-e329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 567] [Cited by in RCA: 872] [Article Influence: 290.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Diwan AD, Melrose J. Intervertebral disc degeneration and how it leads to low back pain. JOR Spine. 2023;6:e1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mohd Isa IL, Teoh SL, Mohd Nor NH, Mokhtar SA. Discogenic Low Back Pain: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatments of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lazaro-Pacheco D, Mohseni M, Rudd S, Cooper-White J, Holsgrove TP. The role of biomechanical factors in models of intervertebral disc degeneration across multiple length scales. APL Bioeng. 2023;7:021501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Farley T, Stokke J, Goyal K, DeMicco R. Chronic Low Back Pain: History, Symptoms, Pain Mechanisms, and Treatment. Life (Basel). 2024;14:812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jha R, Bernstock JD, Chalif JI, Hoffman SE, Gupta S, Guo H, Lu Y. Updates on Pathophysiology of Discogenic Back Pain. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oichi T, Taniguchi Y, Oshima Y, Tanaka S, Saito T. Pathomechanism of intervertebral disc degeneration. JOR Spine. 2020;3:e1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Lin CC, Chenot JF, van Tulder M, Koes BW. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:2791-2803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 963] [Article Influence: 120.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Farag M, Rezk R, Hutchinson H, Zankevich A, Lucke‐Wold B. Intervertebral disc degeneration and regenerative medicine. Clin Transl Discov. 2024;4:e289. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Romaniyanto, Mahyudin F, Sigit Prakoeswa CR, Notobroto HB, Tinduh D, Ausrin R, Rantam FA, Suroto H, Utomo DN, Rhatomy S. An update of current therapeutic approach for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: A review article. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;77:103619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chang Y, Yang M, Ke S, Zhang Y, Xu G, Li Z. Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma on Intervertebral Disc Degeneration In Vivo and In Vitro: A Critical Review. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:8893819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang J, Liu D, Gong Q, Chen J, Wan L. Intradiscal Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for Discogenic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Trial. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:9563693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Apostolakis S, Kapetanakis S. Platelet-Rich Plasma for Degenerative Spine Disease: A Brief Overview. Spine Surg Relat Res. 2024;8:10-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mohammed S, Yu J. Platelet-rich plasma injections: an emerging therapy for chronic discogenic low back pain. J Spine Surg. 2018;4:115-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Machado ES, Soares FP, Vianna de Abreu E, de Souza TADC, Meves R, Grohs H, Ambach MA, Navani A, de Castro RB, Pozza DH, Caldas JMP. Systematic Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma for Low Back Pain. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang H, Zhu J, Xia Y, Li Y, Fu C. Application of platelet-rich plasma in spinal surgery. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1138255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kawabata S, Akeda K, Yamada J, Takegami N, Fujiwara T, Fujita N, Sudo A. Advances in Platelet-Rich Plasma Treatment for Spinal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:7677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mann SJ, Stretanski MF, Singh P. McKenzie Back Exercises. 2025 Jul 7. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Muthu S, Krishnan A, Ramanathan KR. Standardization and validation of a conventional high yield platelet-rich plasma preparation protocol. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;82:104593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Park JW, Nam HS, Cho SK, Jung HJ, Lee BJ, Park Y. Kambin's Triangle Approach of Lumbar Transforaminal Epidural Injection with Spinal Stenosis. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35:833-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pretorius J, Mirdad R, Nemat N, Ghobrial BZ, Murphy C. The efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections compared to corticosteroids and physiotherapy in adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop. 2024;47:35-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Serya SSMA, Neseem NO, Shaat RM, Nour. a. K, Senna MK. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injection in comparison to physical therapy for treatment of chronic partial supraspinatus tear. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil. 2021;48:10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Akeda K, Ohishi K, Masuda K, Bae WC, Takegami N, Yamada J, Nakamura T, Sakakibara T, Kasai Y, Sudo A. Intradiscal Injection of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Releasate to Treat Discogenic Low Back Pain: A Preliminary Clinical Trial. Asian Spine J. 2017;11:380-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jain D, Goyal T, Verma N, Paswan AK, Dubey RK. Intradiscal Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for Discogenic Low Back Pain and Correlation with Platelet Concentration: A Prospective Clinical Trial. Pain Med. 2020;21:2719-2725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tuakli-Wosornu YA, Terry A, Boachie-Adjei K, Harrison JR, Gribbin CK, LaSalle EE, Nguyen JT, Solomon JL, Lutz GE. Lumbar Intradiskal Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Injections: A Prospective, Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Study. PM R. 2016;8:1-10; quiz 10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Levi D, Horn S, Tyszko S, Levin J, Hecht-Leavitt C, Walko E. Intradiscal Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for Chronic Discogenic Low Back Pain: Preliminary Results from a Prospective Trial. Pain Med. 2016;17:1010-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ruiz-Lopez R, Tsai YC. A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Pilot Study Comparing Leucocyte-Rich Platelet-Rich Plasma and Corticosteroid in Caudal Epidural Injection for Complex Chronic Degenerative Spinal Pain. Pain Pract. 2020;20:639-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bodor M, Toy A, Aufiero D. Disc Regeneration with Platelets and Growth Factors. In: Lana J, Andrade Santana M, Dias Belangero W, Malheiros Luzo A, editors. Platelet-Rich Plasma. Lecture Notes in Bioengineering. Berlin: Springer, 2014. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Xu Z, Wu S, Li X, Liu C, Fan S, Ma C. Ultrasound-Guided Transforaminal Injections of Platelet-Rich Plasma Compared with Steroid in Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Study. Neural Plast. 2021;2021:5558138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gupta A, Chhabra HS, Singh V, Nagarjuna D. Lumbar Transforaminal Injection of Steroids versus Platelet-Rich Plasma for Prolapse Lumbar Intervertebral Disc with Radiculopathy: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Pilot Study. Asian Spine J. 2024;18:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wongjarupong A, Pairuchvej S, Laohapornsvan P, Kotheeranurak V, Jitpakdee K, Yeekian C, Chanplakorn P. "Platelet-Rich Plasma" epidural injection an emerging strategy in lumbar disc herniation: a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Navani A, Hames A. Platelet-rich plasma injections for lumbar discogenic pain: A preliminary assessment of structural and functional changes. Tech Reg Anesthesia Pain Manag. 2015;19:38-44. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bhatia R, Chopra G. Efficacy of Platelet Rich Plasma via Lumbar Epidural Route in Chronic Prolapsed Intervertebral Disc Patients-A Pilot Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:UC05-UC07. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Singh GK, Talawar P, Kumar A, Sharma RS, Purohit G, Bhandari B. Effect of autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on low back pain in patients with prolapsed intervertebral disc: A randomised controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2023;67:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cheng J, Santiago KA, Nguyen JT, Solomon JL, Lutz GE. Treatment of symptomatic degenerative intervertebral discs with autologous platelet-rich plasma: follow-up at 5-9 years. Regen Med. 2019;14:831-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Guerrero-Molina AL, Cruz-Álvarez MG, Tenopala-Villegas S. [Bibliographic review of the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma treatment in lumbar disc herniation]. Acta Ortop Mex. 2023;37:290-295. [PubMed] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/