Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110510

Revised: July 9, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 192 Days and 17.6 Hours

The surgical treatment of severe scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis in the pediatric population is complicated and has high morbidity and mortality risks. Severe scoliosis has traditionally been defined by a coronal Cobb angle of greater than 90° or 100°. The usual corrective methods for these patients have been anterior or posterior release and osteotomies using a combined anterior-posterior or poste

Core Tip: Halo gravity traction (HGT) provides a safe and gradual approach to more severe scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis in the pediatric population, while decreasing the risk of surgery, as well as improving spinal flexibility, pulmonary function, and nutritional status. It minimizes the need for extensive procedures like vertebral column resection. Even though protocols do vary, there is initial evidence to support 3-11 weeks of traction, and to monitor carefully for pin-site complications as well as neurological complications for monitoring of HGT in children. Overall, HGT serves to improve surgical safety and or outcome for children with complex spinal deformities.

- Citation: Jain MA, Dhawale A, Iqbal MZ, Naseem A, Sagade B, Gorain A, Nene A. Halo gravity traction for pediatric scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis: A review of current evidence and best practices. World J Orthop 2025; 16(12): 110510

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i12/110510.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110510

Recent developments in traction techniques are transforming the approach to eliminating extreme spinal deformities. Early techniques utilizing cranial tongs had significant risks of permanent neurological injury and limited application[1,2]. In the 1950s and 1960s, Nickel et al[3] at Rancho Los Amigos Hospital introduced the halo-plaster vest, an innovative treatment for post-polio paralytic spinal deformities. Stagnara developed halo gravity traction (HGT) in the latter part of the 1970s, altering the system to be used in a wheelchair to gradually physiologically correct spinal deformities safely and effectively[4]. Stagnara also looked closely at the consideration of contraindications for HGT, including cervical kyphosis, spinal stenosis, cervical instability, and ligamentous laxity. Refinements of, specifically, traction, continue to expand available treatment options and increase the benefits and decrease possible complications when considering surgical options to treat severe spine deformity.

This review shall provide a thorough overview of HGT in the pediatric population with scoliosis or kyphoscoliosis. We will cover the biomechanical principles of HGT, the indications and contraindications, application techniques, post-traction protocols, clinical benefit, possible complications, and considerations for prevention and management.

The rationale for using HGT is its ability to further improve the spinal deformity, flexibility, and decrease the risk of neurologic complications during the operation[5-7]. HGT utilizes the principles of skeletal traction and gravity-assisted countertraction (Figure 1). It can negate the decompensation caused by gravity in a progressive curve. The results of repeated long-term loading with external weight over weeks to months (depending on age, severity of the deformity, and condition of the spine) can provide a linear or axial release or stretch effect with a response similar to that of liga

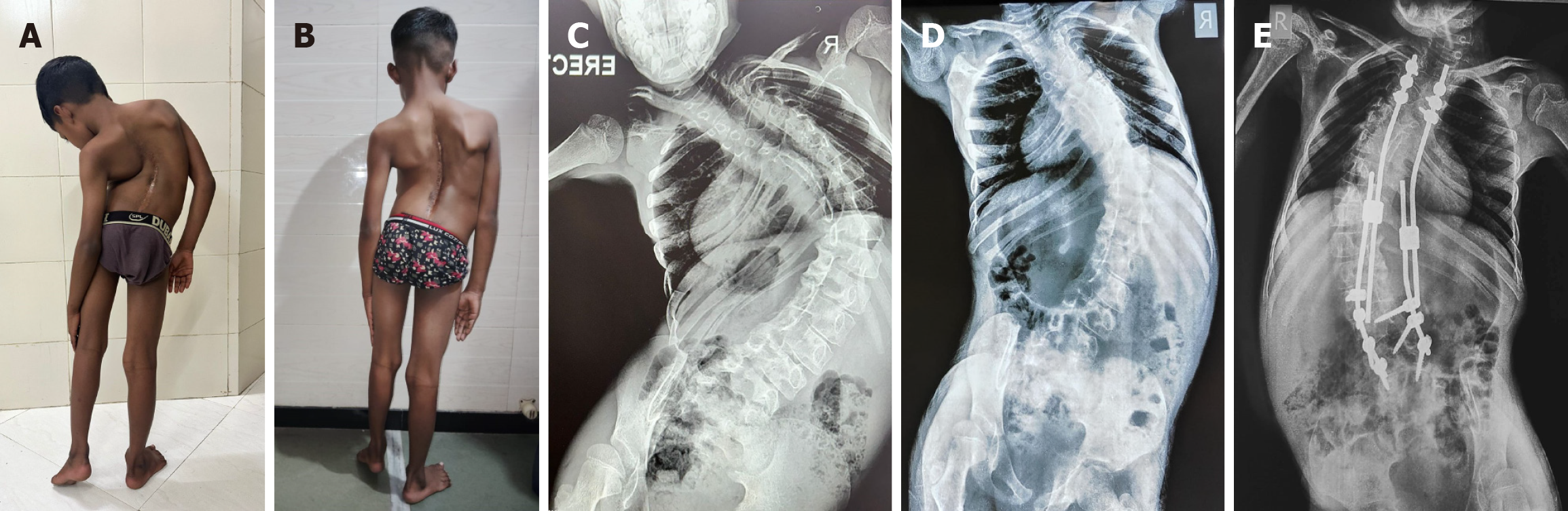

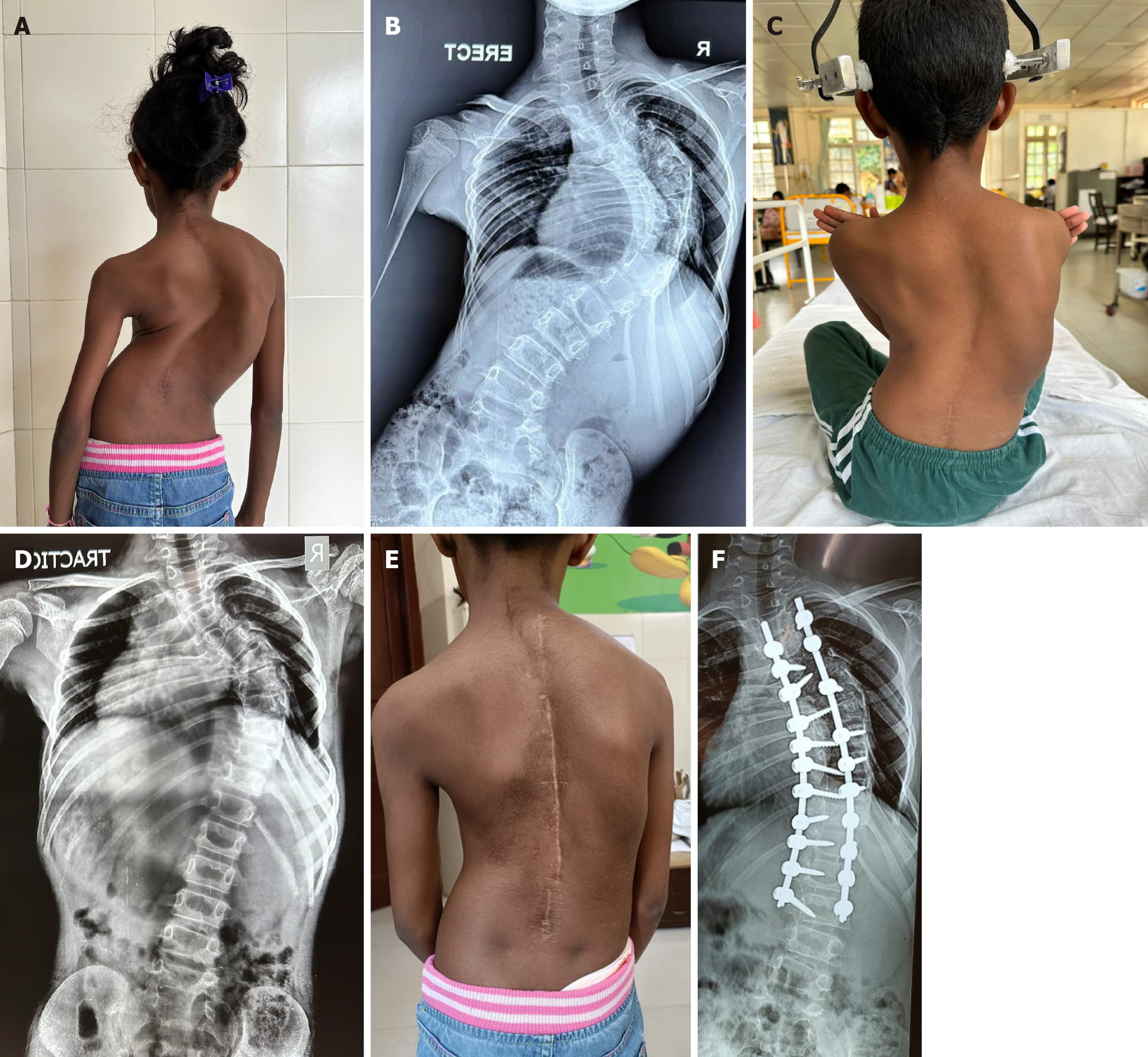

The HGT has been used for various indications in literature, but there are no standardized guidelines for its use in scoliosis correction. The most well-established indication is for severe scoliosis or kyphoscoliosis. The literature defines a severe deformity as one with an upright Cobb angle of more than 90°-100°. Also, these patients may demonstrate severe restrictive patterns on their pulmonary function tests before surgery (Figure 2), if evaluated with preoperative pulmonary function tests. Absolute contraindications include spinal instability, intradural or extradural lesions, severe canal stenosis, cranial fractures, being under 1 year of age or having open fontanelles, and cutaneous lesions or wounds over potential pin sites. Relative contraindications include polytrauma, severe chest trauma, and systemic skeletal fragility such as osteogenesis imperfecta.

Preoperative HGT has unique benefits for children with a diagnosis of severe scoliosis (or kyphoscoliosis), which can have multiple interrelated challenges. These challenges can include diminished respiratory function, elevated risk of neurological compromise, increased intraoperative blood loss, and/or poor nutritional status[10]. In providing a safe, gradual trajectory toward improvement, HGT may improve patient’s spinal flexibility, pulmonary function, and provide improvement in bodily function in general before definitive surgery to improve intraoperative risk and postoperative complications.

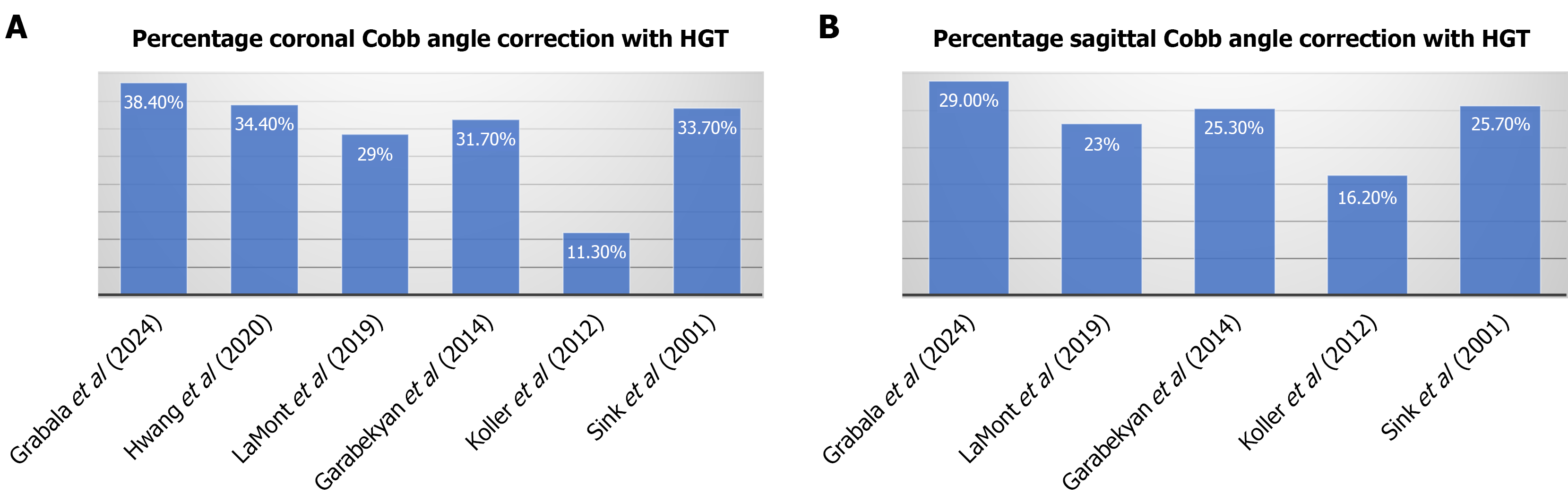

HGT provides gradual correction of the complex three-dimensional deformity throughout the coronal, sagittal, and axial planes before undergoing definitive surgery (Figure 3). Literature described a variable degree of correction in the sagittal and coronal planes (Figure 4). Bogunovic et al[11] reported an average improvement of 35% (in both planes) in a cohort of patients who underwent HGT. This correction before a definitive surgery has been shown to reduce the requirement of vertebral column resection (VCR). Consistent with the above findings, Sponseller et al[12] compared cohorts with and without preoperative HGT. They revealed a VCR rate of 3% in patients who had undergone preoperative HGT, compared to a 30% in those treated without HGT, a statistically significant difference. They concluded that VCR could be avoided in a significant number of patients who underwent pre-operative HGT. In patients who have been treated with HGT, the apparatus was also used intra-operatively, with the maximum weight tolerated by the patient prior to surgery, being applied for traction intra-operatively.

Poor bone quality is frequently associated with severe spinal deformities[13]. When correction is attempted without preoperative HGT, the definitive construct often requires extensive rod contouring, which imposes high mechanical stress at the bone-implant interface and increases the risk of early or gradual implant failure[14]. By contrast, if substantial correction is achieved preoperatively with HGT, in-situ definitive fusion can be performed. This reduces the mechanical load on the construct, minimizes stress at the bone-implant junction, and subsequently lowers the likelihood of implant failure[5].

The most frequent cause of neurological deficit during spinal deformity correction is the application of excessive traction over a short period of time. HGT mitigates this risk by providing gradual, sustained correction, allowing progressive stretching of the soft tissues and spinal cord. This process is thought to “train” the cord to accommodate further correction safely[15]. Moreover, HGT permits serial neurological assessment in the awake patient, thereby reducing the likelihood of unrecognized neurologic injury that may occur with rapid intraoperative correction[16].

Restrictive pattern in pulmonary function test (PFT) arises due to chest wall deformities caused by severe scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis. Ineffective diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle function due to the underlying neuromuscular or syndromic associations typically worsens respiratory compromise.

The effect of distraction-based correction techniques on pulmonary function has been examined in several studies (Table 1)[6,11,17]. Bogunovic et al[11] assessed 33 patients and reported an average improvement of at least 20% in PFT values after traction compared to baseline values. Koller et al[6] assessed a similar variable on patients with severe, rigid scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis via HGT, and noted a mean forced vital capacity (FVC) increase of 7.0% from the initial PFT to the final PFT during traction. Glotzbecker et al[18] examined the relationship between thoracic dimensions and pulmonary functioning among patients with scoliosis. They reported that T1-T12 height, T1-S1 height, maximum chest width, and pelvic inlet width all had a significant correlation with PFTs. Thus, improving thoracic dimensions will improve respiratory function. In a series of 107 patients assessed by LaMont et al[19], there was a significant improvement in mean thoracic height (T1-T12), where traction accounted for 78% of the T1-T12 height gain. There was a 14.5% and 24% improvement in FVC percentage of predicted value and FVC absolute value, respectively, from pre-traction to two-year follow-up. Bumpass et al[17] examined the effect of correction of severe spinal deformity in a pediatric population. In pediatric patients, improved PFTs were correlated with younger age and pre-operative HGT. The authors concluded that the improvement in PFTs was due to the presence of growth potential of the lung and thoracic cage following correction of deformity.

| Ref. | Year | Sample size | Mean follow-up | Pre-traction FVC/FEV1 | Post traction FVC/FEV1 | FVC/FEV1 at final follow-up |

| Grabala et al[38] | 2024 | 20 | 3.8 years | 54.5%/60.8% | 66.7%/70.1% | 74.9%/75.9% |

| LaMont et al[19] | 2019 | 107 | 2 years | 38%/37.7% | 43.9%/42.1% | 43.5%/43.2% |

| Koller et al[6] | 2012 | 45 | 33 months | FVC%-49.5% | FVC%-49.5% | FVC%-45% |

| Wang et al[28] | 2024 | 33 | NA | 43.5%/41.9% | 47.3%/45.2% | NR |

| Iyer et al[9] | 2019 | 30 | 16 months | 75.43%/64.35% | 68.11%/ 60.83% | NR |

| Garabekyan et al[16] | 2014 | 21 | 2.4 years | FVC-1.31 L, FEV1-1.01 L | FVC-1.61 L, FEV1-1.3 L | NR |

| Bogunovic et al[11] | 2013 | 33 | NA | 45.4%/43.7% | 53.1%/52.7% | NR |

Patients with severe scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis typically present with a low body mass index and poor nutritional status. On initial and continued HGT, some studies have noted improvements in nutrition (Table 2). Several studies have recommended focused nutritional build-up strategies to address nutrition during traction. McIntosh et al[10] reported that the mean weight for the majority of their patients in HGT was 4.3 SD below the mean. However, they provided regular nutritional supplementation and improved the weight to within 2 SD below the mean by the 11th week of traction using the dietitian and rehabilitation program. Additionally, a poor pre-operative nutritional status has been identified as an independent risk factor for unplanned admission within 30 days of spine surgery[20]. Hence, poor nutritional status, pre-operatively, is a known modifiable risk factor to reduce complications after surgery.

| Ref. | Year | Sample size | Mean follow-up | Mean age at surgery (years) | BMI before traction (kg/m2) | BMI at surgery (kg/m2) | Duration of halo in days | Maximum weight applied (SD) |

| Wang et al[28] | 2024 | 33 | NA | 17.79 | 17.2 ± 3.9 | 17.7 ± 3.7 | 129 ± 63 | 45.2% (± 13.2%) of body weight |

| Iyer et al[9] | 2019 | 30 | 16 months | 9.0 | 15.1 ± 1.9 | 16.1 ± 2.0 | 79 ± 43 | 50% of body weight |

Toombs et al[21] conducted a retrospective study of 393 patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis from developing countries. They concluded that more severe curves at the time of surgery correlated with greater blood loss. Therefore, a pre-operative reduction in the severity of the curve by HGT, can reduce the intraoperative blood loss.

The halo ring must be placed in accordance with the anatomical considerations for safe pin placement (Figure 5). For appropriate pre-operative planning, a pre-operative computed tomography scan of the skull must be performed to measure the thickness of the skull. The thickness of the skull is not a uniform measurement, as there are anatomical differences in skull thickness. The greatest thickness of the skull is in the direct posterior area, followed by the direct anterior, posterolateral, anterolateral, and the direct lateral in that order.

There are specific guidelines to consider for safe and effective pin placement. The ring must be placed at or below the maximum width of the skull. The skull-to-ring distance must be at each pin-site within 1 cm whenever possible. Pins should be placed as perpendicular to the bone at each pin-site as possible[22]. The treating surgeon must be aware of the following pin insertion safe zones: Antero-lateral pins - preferably 1 cm above the lateral margin of the eyebrow. Thus, it is medial to the temporalis muscle and lateral to the supra-orbital and supra-trochlear nerves, postero-lateral pins - preferably 1 cm posterior and above the pinna of the ear. There should be no fewer than six pins in children, as per the consensus[23]. One should avoid the following sites for pin insertion: Direct anterior - to prevent violating the frontal sinus or damaging the supra-orbital nerve, direct posterior - in the supine position, the posterior pin would have direct pressure and impact sleep, direct lateral - the thinnest section of the skull, therefore a maximum chance of breaching the temporal fossa. Also, direct lateral pins can tether the temporalis muscle and affect chewing.

As a general rule, McIntosh et al[10] state that torque in inch-pound will be approximately equal to that child’s age until 8 years of age. Therefore, for a 4-year-old, the pins would be tightened to a torque of 4 inch-pounds. Certain torque-limiting wrenches are available to achieve this. Numerous children undergoing a halo frame application have either abnormal anatomy or metabolic bone disease. For these patients, and for anyone less than 5 years of age, Bauer et al[14] recommended using ‘finger-tightened torque’ because it has better tactile feedback in thin skulls.

The equipment needed for the application of the halo frame include a halo ring that is appropriately sized, at least six pins, two positioning pins, a torque-limiting wrench, appropriately sized spanners, a local anesthetic of your choosing, as well as two assistants to stabilize the frame and one surgeon to insert the pins[14,24] The application of the halo frame is performed under general anesthesia. Local anesthesia can be infiltrated around the pre-determined pin sites either before or after pin insertion. The patient should be positioned supine on a standard table, providing adequate room surrounding the head for ease of movement while placing the pins. As described before, the ring should be placed below or at the level of the maximum width of the skull. When the ring is correctly positioned, it can be temporarily stabilized with two positioning pins on either side of the ring.

The first four pins should be inserted into two diagonally opposite holes in each of the safe zones and be finger-tightened until the pins contact the skin. After that, two diagonally opposite pins are tightened to the appropriate torque, followed by tightening the remaining two diagonally opposite pins. After those four pins have been engaged and tightened to round, the last two pins can be placed according to your predetermined plan and available space (Figure 6A). Once all pins are secured, mild traction is applied to the frame to confirm proper fixation and stability (Figure 6B and C).

There is no agreement about the duration to maintain the halo. Various authors have advocated for different durations of application (Table 3). Park et al[25] stated maximum correction occurred within 2 weeks, while Hwang et al[26] and Letts et al[27] found maximum correction occurred during the first week, and Wang et al[28] applied traction for an average of 18 weeks in their study. Hwang et al[26] also recommended that traction in excess of 3 weeks would not be beneficial. However, the majority of authors tend to apply traction between 3 weeks and 11 weeks[6,19,25,26]. The time to apply traction can be based on the magnitude, flexibility of the curve, and patient response to HGT. If the surgeon believes the patient would benefit from considering additional time in traction, the surgery should be deferred[23].

| Ref. | Year | Sample size | Mean follow-up | Mean age at surgery (years) | Mean traction time | Maximum weight applied (% body weight) | Coronal Cobb correction | Sagittal Cobb correction | ||||||

| Pre-traction coronal Cobb (degrees) | Post traction coronal Cobb (% correction) | Coronal Cobb after surgery (% correction) | Cobb at final follow-up | Pre-traction sagittal Cobb | Post traction sagittal Cobb (% correction) | Sagittal Cobb at final surgery (% correction) | Sagittal Cobb at final follow-up | |||||||

| Grabala et al[38] | 2024 | 20 | 3.8 years | 16.5 | 36 days | 50 | 124 | 76.4 (38.4) | 45 (63.7) | 44.09 | 96.5 | 68.5 (29) | 45.8 (52.5) | 44 |

| Hwang et al[26] | 2020 | 59 | NA | 15.2 | 3.1 weeks | 44 | 96.98 | 63.38 (34.4) | 32.58 (65.9) | 39.4 | 26.5 | NA | 22.2 (16) | 23.5 |

| LaMont et al[19] | 2019 | 107 | 2 years | 11.3 | 82.1 days | 49.50 | 92.6 | 65.8 (29) | 47 (50) | 48.4 | 74 | 56.8 (23.2) | 47.7 (35.5) | 50.9 |

| Garabekyan et al[16] | 2014 | 21 | 2.4 years | 13 | 77 days | 50 | Major curve-101; compensatory minor curve-63 | Major curve-69 (31.6); compensatory minor curve-41 (34.9) | Major curve-58 (43); compensatory minor curve-39 (38) | Major curve-62; compensatory minor curve-44 | 67 | 50 (25.4) | 47 (29.8) | 50 |

| Koller et al[6] | 2012 | 45 | 33 months | 24 | 30 days | 33 | 106 | 94 (11.3) | 76 (28.3) | 84 | 90.7 | 76 (16.2) | 70 (22.8) | 76 |

| Sink et al[5] | 2001 | 21 | NA | 7.4 | 13 weeks | 25 to 50 | 83 | 55 (33.7) | 51 (38.5) | 61 | 97 | 72 (25.8) | NA | 82 |

Once the child is comfortable in the halo frame, weight is generally applied beginning on day two. Weight is applied slowly, starting with 1 kg or 2 kg. Each day, the weight can be increased (by 1 kg or 2 kg) based on tolerance. The weight may be increased up to a maximum of 50% of the body weight. The patient may complain of discomfort, neck pain, and pin-site pain. In these situations, the weight may be decreased for a period of time and re-established once the pain is relieved. The weight should be applied full-time, but at night while sleeping, the weight can be decreased for the comfort of the child. At night, the weight can be hung on the end of the bed with a pulley, along with a raised head end.

Pin-site dressing should be changed daily, and vigilance for pin-site infection is paramount. The authors recommend daily dressing with sterile precautions and normal saline to clean the pin-site. Patients should be monitored daily for neurological status, including cranial nerve and brachial plexus examination. Special attention to the examination should be performed when the traction weight is increased.

Some centers allow for an inpatient facility of traction application; in these cases, the patients can see a respiratory therapist and a dietician daily. This can allow for improvement in the overall nutritional status of the child while the child is receiving HGT. In an outpatient setting, the patients are discharged when they are comfortable enough and are seen weekly for pin-site review. In the outpatient setting, however, compliance with traction cannot be monitored.

After a child has achieved the target correction in the frame, the definitive surgery is planned. The halo frame is used intraoperatively to maintain correction of the deformity, with the maximum tolerated weight during the traction phase being applied during the definitive surgery (Figure 7).

Complications associated with HGT have been well-documented in the literature through numerous case series and categorized into three types: Halo-ring related, traction force related, or neurological complications[29].

Pin loosening: Most common complication, occurring in approximately 30%[9]. More prevalent in the older age group and common in anterior pins as opposed to posterior. The neuromuscular scoliosis group has a higher incidence of pin loosening.

Pin-site infection: More common in children than adults or neuromuscular groups. Two types, superficial and deep, have been described in the literature.

Pin penetration/mispositioning: More likely to occur in younger children with thin skulls due to the over-tightening of pins, which can lead to cranial osteomyelitis and possible brain abscess[30]. Mispositioning can lead to injury to the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, which may manifest as pain or paresthesia over the forehead region.

Pressure sores: These are more frequently observed in non-ambulatory, neuromuscular type patients and in older age individuals.

Complications associated with traction forces, relate to the amount of traction force applied and the length of time traction is applied for. Such complications are primarily related to the halo-pelvic traction, but at least in the case of HGT, the same precautions should also apply. Tredwell and O'Brien[31] noted cervical apophyseal degeneration in 47.4% of patients in their series. O'Brien et al[32] stated there was a 50% rate of degenerative changes in the cervical spine after 3.5 years of surgery, when high traction factors or traction times were reached. Rinella et al[29] obtained weekly cervical spine radiographs in their series to prevent over-distraction. As a rule, traction beyond 50% of body weight was not applied. Transient neurodeficit was also documented; however, they were reversible with a decreased traction force.

According to Popescu et al[33], the incidence of neurological complications was as high as 26.3% of patients. Some patients presented with headache, vertigo, upper limb numbness, and transient palsy. None of the patients in their series had any permanent neurological deficit due to traction. Qian et al[34] reported transient brachial plexus palsy, which fully recovered following three months of rehabilitation and drug therapy. Thin soft bone in young children, osteomalacia, and poor nutritional status are some of the patient-related risk factors for hardware loosening-related complications, but neuromuscular scoliosis is one of the etiologies linked to a high complication rate[33]. In addition to the above complications that occur later in the course of treatment, early complications can occur if the standard technique of pin insertion with the safe zones is not utilized as described above.

The most commonly experienced complication is pin site infection or loosening, which occurs in nearly 30% of patients. Our standard care of pin-sites is to dress once per day with saline. If the pin-site has both pain and redness, we re-dress twice per day and start the patient on oral antibiotics. If the infection worsens, with discharge from the pin-site, we use IV antibiotics, along with dressings using 5% povidone-iodine solution. If this fails, we remove the pin, do thorough debridement, and select a new site to insert a new pin. Iyer et al[9] report the rate of halo revision due to infection is 6.7%.

Traction-related injuries result from the duration and amount of traction given. Therefore, in the case of HGT, the amount of traction was limited to 50% of body weight. In the case of a developing neurodeficit, the weight is lowered promptly by 2 kg, and the patient is observed for recovery.

Since HGT also has contraindications and complications, a few authors have tried other approaches as an alternative to managing severe scoliosis with rigid curves to potentially shorten hospital stays and other complications.

Discussing Buchowski et al[35] in a cohort of 10 patients who had temporary internal distraction (TID) with posterior and/or anterior releases. The patients had 1-2 episodes of distraction and final surgical fusion. They reported a mean curve correction of 53% after release and distraction, and an 80% mean correction after surgical fusion, when comparing the preoperative Cobb angle. The authors mentioned that the technique provided preservation of normal thoracic lordosis and kyphosis in nearly every patient. There were no neurologic complications reported in their cohort. The authors mentioned equivalent results to other patients with HGT, with the relative benefit of shorter hospital stay (Table 4). Cheng et al[36] conducted a similar study based on TID, and then staged posterior fusion. They reported 46% and 60.4% improvements in the major coronal curve, as well as a 50.9% and 64.8% improvement in thoracic kyphosis after the first and final surgery. There was also a reported statistically significant improvement with follow-up PFTs and nutritional status after surgery. Hu et al[37] investigated a subset of patients exhibiting scoliosis with an angle of > 130° with a similar treatment algorithm. The Cobb angle in this group improved from an average of 148.8° before surgery to 55 degrees after final fusion. They concluded that the use of TID resulted in significantly less risk than HGT and VCR. It demonstrated a high level of correction of the spinal deformities and PFT with minimal complications.

| Ref. | Sample size | Preoperative deformity | Deformity after temporary internal distraction (stage 1) | Deformity after final fusion (stage 2) | Complication | Blood loss | FEV1% | FVC% | Loss of correction at final follow up |

| Cheng et al[38] | 18 | Cobb angle: 129.8°; K angle: 94.7° | Cobb angle: 70.5°; K angle: 46.2° | Cobb angle: 51.8°; K angle: 32.9° | Intraoperative loss of SSEP signals in 1 case; pleural effusion in 2 cases; subcutaneous hydrops in 1 case; no permanent neurodeficit, infection, implant failure | 211 mL in stage 1; 1597 mL in stage 2 | 58.6 to 67.6 (stage 1) | 61.2 to 70.3 (stage 1) | 3.3° of coronal correction and 2.6° of sagittal correction lost at final follow up |

| Hu et al[37] | 11 | Cobb angle: 149°; K angle: 79° | Cobb: 79°; K angle: 59° | Cobb angle: 55°; K angle: 35° | Paralytic ileus in 1 which resolved conservatively; no neurodeficit; no implant failure | 210 mL in stage 1; 1512 mL in stage 2 | 61.4 to 71.3 (stage 1); 71.3 to 76.3 (stage 2) | 59.3 to 68.7 (stage 1); 68.7 to 71.2 (stage2) | No significant deterioration in spinal alignment or PFT |

| Buchowski et al[35] | 10 | Cobb angle: 104° | Cobb angle: 49° | Cobb angle: 20° | Spontaneous pneumothorax in one case; one death unrelated to surgery; no neurodeficit, infection or implant failure | NR | NR | NR | NR |

The studies previously discussed only described the use of TID alone, and there was no direct comparison of TID and HGT. Grabala et al[38] conducted a comparative study of two groups of patients with severe scoliosis. They documented 63% and 70% improvement in coronal deformity, and 55% and 60% improvement in sagittal deformity with the HGT and TID surgeries, respectively. Surgery improved lumbar lordosis and anterior vertebral translation. Trunk height showed greater benefits with HGT. Both of these procedures showed significant improvement in PFT, and there were no differences in improvement in PFT between the two groups. The Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22) score improved significantly from 2.88 to 4.33 in the HGT group and 3.22 to 4.46 in the TID group, with no statistical difference between the groups. According to their study, although the overall complication rate was markedly higher in HGT than in TID, upon closer scrutiny of the data, the only real difference between the two groups was in the incidence of neck and back pain (HGT 55%; TID 7%).

Oliveira et al[39] conducted a comparative study of posterior release followed by HGT or TID, followed by staged posterior fusion. The two groups were similar regarding clinical and surgical characteristics before surgery. Patients not subjected to HGT needed larger number of VCR and had lower implant density. They concluded no procedure as superior to the other although HGT may be safer in the hands of less experienced surgeon (Table 5).

| Ref. | Sample size | Preoperative deformity | Deformity after temporary internal distraction (stage 1) | Deformity after final fusion (stage 2) | Complication | Blood loss (mL) | FEV1% | FVC% | Loss of Correction at final follow up | |

| Grabala et al[38] | HGT | 20 | Cobb angle: 124°; K angle: 96.5° | NA | Cobb angle: 45°; K angle: 45.8° | Neuromonitoring alerts in 15% cases; pin tract infection: 35%; deep infections: 5%; pneumonia: 10%; neck/back pain: 55% | 588 | 60.8 to 70.1 after HGT; 74.4 after fusion; 74.9 at final follow-up | 54.5 to 66.7 after HGT; 73.4 after fusion; 75.9 at final follow up | NR |

| TID | 42 | Cobb angle: 122°; K angle: 92° | NA | Cobb angle: 37.4°; K angle: 36.2° | Neuromonitoring alerts in 12% cases; deep infections: 2%; pneumonia: 5%; neck/back pain: 7% | 282 + 458 in each stage | 58 to 66 after TID; 71.2 after fusion; 78 at final follow up | 49 to 55.2 after TID; 67 after fusion; 76 at final follow up | NR | |

| Oliveira et al[39] | HGT | 12 | Cobb angle: 104.6°; K angle: 43.5° | Cobb after HGT: 85.6° | Cobb angle: 49.5°; K angle: 30.3° | Intraoperative neurodeficit: 3 cases; pneumothorax: 6 cases; implant failure: 1 case; infection: 1 case | 1642.22 ± 1058.79 | NA | NA | NR |

| TID | 7 | Cobb angle: 100°; K angle: 40.7° | Cobb after TID: 94.7° | Cobb angle: 39.5°; K angle: 30.5° | Intraoperative neurodeficit: 4 cases; pneumothorax: 3 cases; implant failure: 2 cases; infection: 1 case | 1400.00 ± 718.33 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Caubet and Emans[40] | HGT | 13 | Cobb angle: 92°; K angle: 99.5° | NA | Cobb angle: 40% improved | 3 patients with neurodeficit; implant loosening in 7 patients | NA | NA | NA | Loss of kyphosis correction: 29%; loss of scoliosis correction: 20% |

| SR | 14 | Cobb angle: 73.3°; K angle: 67.6° | NA | Cobb angle: 63% improve | 2 patients with neurodeficit; implant loosening in 9 patients | NA | NA | NA | Loss of kyphosis correction: 26%; loss of scoliosis correction: 9% | |

| Control group | 71 | NA | Cobb angle: 41% improved | 3 patients with neurodeficit; implant loosening in 20 patients | NA | NA | NA | Loss of kyphosis correction: 15%; loss of scoliosis correction: 5% |

The HGT has relatively scant long-term data on curve progression. Several authors reported short-term to mid-term radiological or clinical parameters[5,29,38]. Grabala et al[38] demonstrated the superiority of the correction with two years of follow-up on curve correction. They reported a change in Cobb angle from 124 degrees before halo, and 76 degrees after traction (61% correction). Following final surgery, this improved to a 44-degree Cobb angle, and this same Cobb angle was maintained at 2-year follow-up of 45 degrees. Final follow-up at 2 years demonstrated no significant differences regarding thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, apical vertebral translation, or thoracic height. In terms of pulmonary function, they reported a significant difference in predicted FVC percentage in the HGT group. Additionally, predicted forced expiratory volume 1 values similarly demonstrated significant differences during follow-up.

Sink et al[5] presented a retrospective study in a cohort of 12 patients who were treated with preoperative halo traction followed by posterior fusion (with or without instrumentation). These authors reported some loss of correction in the radiographs following spinal fusion surgery. They reported an average loss of correction in the Cobb angle of 9.5° at 1 year. The average loss of correction in the sagittal plane was 10.8 degrees. The authors noted a greater maintenance of the correction in the instrumented curves.

Rinella et al[29] performed a retrospective assessment in 33 cases of severe scoliosis managed with a staged approach with a variable period of HGT application, with a mean follow-up of 44 months and an average age of surgery of 13.2 years. They demonstrated a correction of mean coronal Cobb from 84° to 46° with a preserved final follow-up angle of 53°. Similarly, the mean sagittal Cobb angle was corrected from 78° to 46°, with a preserved final follow-up angle of 51°. There was a loss of correction of 7° in the sagittal plane and 4° in the coronal plane. Curve progression occurred in 2 of the 33 patients who were revised later. Literature supports that the curve correction is maintained at final follow-ups. These patients do require long-term follow-up to check curve progression, especially if it is in the context of early surgery and patients have growth potential.

The HGT has been recommended as a possible treatment to be used with anterior spinal releases and bracing to obtain partial correction. This could be used to subsequently place guided growth or growing rod constructs. Iyer et al[9] in their series reported outcomes of pre-operative halo traction used before guided growth/growing rod surgery. They demonstrated improvements of 29 % in both sagittal and coronal deformity, which was corrected further during growth rod surgery to an improvement of 40% and 35%, respectively. In their 16-month follow-up data, the reoperation rate was 23% (7 patients) for various reasons.

Caubet and Emans[40] conducted a comparative analysis of surgical release and HGT before the implantation of the growing rod or expandable device. The correction of scoliosis immediately post-operatively was 40% and kyphosis was 48%. The increase in thoracic spine length and height was also greater in the HGT group compared to the surgical release group. In the long-term results, following their multiple planned distractions, the correction of kyphosis was greater in the HGT group, while scoliosis correction was better in the surgical release group. Furthermore, the thoracic spine length and height were improved more in the HGT group than in the surgical release group. At the final follow-up, the overall loss in correction of scoliosis and kyphosis that resulted from these procedures was 20% and 29% respectively in the HGT group, and 9% and 26% in the surgical release group. Ultimately, they concluded that HGT is advantageous for patients with severe kyphoscoliosis, given the ease of incorporating expandable devices with it and the difficulty in applying these devices with severe deformity.

In their study, LaMont et al[19] studied 37 patients with early-onset scoliosis who received preoperative halo traction for a mean of 14.7 weeks, with the maximum amount of traction being 57% of the patient’s body weight. After traction, 24 patients underwent treatment with a growing rod construct, 7 underwent posterior spinal fusion, and 6 underwent anterior and posterior fusion. Coronal Cobb improved from 92 degrees pre-traction to 62° post-traction and 47° Cobb angle at 2-year follow-up. Sagittal Cobb improved from 71 degrees preoperative to 51° post-traction and 43° at 2-year follow-up. Improvement in thoracic and spinal height, and nutritional improvements in patients with early-onset scoliosis were also documented.

The HGT can be of value in early-onset scoliosis patients; however, the patients with early-onset scoliosis tend to demonstrate more loss of correction because they have more remaining growth. Therefore, these patients with early-onset scoliosis will need to be monitored even closely because they are at a greater risk of curve progression and implant failures.

The incidence of spinal fusion is not primarily related to the adjunct of HGT. Fusion surgery done in conjugation with HGT has been shown to have a notable union and fusion rate, and only a few instances of non-union or pseudarthrosis formation have been noted. In the Iyer et al[9] series, while all patients met spinal fusion criteria, 7 (23.3%) patients underwent re-operation. The re-operation etiology cited was: Broken implants (10%), deep infection (6.7%), wound dehiscence (3.3%), and other (3.3%). In the Rinella et al[29] series, the re-operation rate was noted to be 6 % (2 cases). One case with anterior graft dislodgement 2 weeks postoperatively, and the other with curve progression and prominent instrumentation. Garabekyan et al[16] in their series noted complications in 8 out of 21 patients, with progression of kyphosis in one patient and pseudarthrosis with painful hardware in another; it is worth noting that the patient with pseudarthrosis had the hardware partially removed and underwent revision bone graft and fusion.

Koller et al[6] performed a thorough study of 45 patients with severe spinal deformity, with a mean follow-up of 33 months, who received preoperative HGT followed by surgically fusing their deformity. They found a significantly improved sagittal and coronal Cobb angle. They also reported improvements in coronal and sagittal balance, improvement in lung function, and a good patient satisfaction rate of 87% at final follow-up. They noted a mean coronal correction loss of 8 degrees and a sagittal correction loss of 6 degrees in their series. Most patients achieved good, solid fusion; however, they recorded two cases of non-union, one case of coronal decompensation, and loss of kyphosis correction. In their study, additional surgery was required for twelve patients (27%), 7 of whom required revision surgery, 7 patients received a rib-hump resection.

In their research, Grabala et al[38] used the SRS-22 revised questionnaire to measure quality of life. The mean pre-operative total score increased significantly from 3.22 to 4.46. In the research of Nemani et al[15], there was a significant improvement in SRS-22 and visual analogue scale. SRS 22 improved from 3.5 to 4.5, and visual analogue scale leg and back improved from 1.5 to 0.6 and 1.6 to 0.4, respectively.

Preoperative HGT is a practical means of sequentially correcting severe scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis. The literature indicates the effectiveness of HGT in improvement of curve magnitude, improvement of Pulmonary function, and a decrease in the risk of neurodeficit, implant failure, and blood loss. Preoperative planning, respecting safe zones, and limiting torque when inserting screws are imperative for successful application of the halo apparatus. There is various post-traction protocols used, with no post hoc data to indicate one protocol is superior to another. A surgeon should be aware of complications and their management. HGTs allow for 30% to 50% correction of the curvature preoperatively. Displacement of the vertebrae in adolescents and adult patients may not be corrected at follow-up; however, children with early-onset scoliosis may lose the correction due to more growth remaining. There is a lack of long-term results of HGT in the literature. Most of the literature is level IV retrospective studies, and more robust research is warranted to allow standardization of practice around the world.

| 1. | Oakley PA, Betz J, Haas JW. A History of Spine Traction. J Vertebral Subluxation Res. 2007;1-12. |

| 2. | Barnett GH, Hardy RW. Gardner tongs and cervical traction. Med Instrum. 1982;16:291-292. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Nickel VL, Perry J, Garrett A, Heppenstall M. The halo. A spinal skeletal traction fixation device. By Vernon L. Nickel, Jacquelin Perry, Alice Garrett, and Malcolm Heppenstall, 1968. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;4-11. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Stagnara P. [Cranial traction using the "Halo" of Rancho Los Amigos]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1971;57:287-300. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sink EL, Karol LA, Sanders J, Birch JG, Johnston CE, Herring JA. Efficacy of perioperative halo-gravity traction in the treatment of severe scoliosis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:519-524. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Koller H, Zenner J, Gajic V, Meier O, Ferraris L, Hitzl W. The impact of halo-gravity traction on curve rigidity and pulmonary function in the treatment of severe and rigid scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis: a clinical study and narrative review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:514-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Watanabe K, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Kim YJ, Hensley M, Koester L. Efficacy of perioperative halo-gravity traction for treatment of severe scoliosis (≥100°). J Orthop Sci. 2010;15:720-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang Z, Liu Y, Qi L, Wu S, Li J, Wang Y, Jiang B. Does Preoperative Halo-Gravity Traction Reduce the Degree of Deformity and Improve Pulmonary Function in Severe Scoliosis Patients With Pulmonary Insufficiency? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:767238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Iyer S, Boachie-Adjei O, Duah HO, Yankey KP, Mahmud R, Wulff I, Tutu HO, Akoto H; FOCOS Spine Research Group. Halo Gravity Traction Can Mitigate Preoperative Risk Factors and Early Surgical Complications in Complex Spine Deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44:629-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McIntosh AL, Ramo BS, Johnston CE. Halo Gravity Traction for Severe Pediatric Spinal Deformity: A Clinical Concepts Review. Spine Deform. 2019;7:395-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bogunovic L, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Luhmann SJ. Preoperative Halo-Gravity Traction for Severe Pediatric Spinal Deformity: Complications, Radiographic Correction and Changes in Pulmonary Function. Spine Deform. 2013;1:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sponseller PD, Takenaga RK, Newton P, Boachie O, Flynn J, Letko L, Betz R, Bridwell K, Gupta M, Marks M, Bastrom T. The use of traction in the treatment of severe spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:2305-2309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ramo BA, Johnston CE. Halo-Gravity Traction. In: Akbarnia BA, Thompson GH, Yazici M, El-Hawary R, editors. The Growing Spine. Cham: Springer, 2022: 485-499. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Bauer JM, Yang S, Yaszay B, Mackenzie WGS. Pediatric Halo Use: Indications, Application, and Potential Complications. J Pediatr Soc North Am. 2024;9:100129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nemani VM, Kim HJ, Bjerke-Kroll BT, Yagi M, Sacramento-Dominguez C, Akoto H, Papadopoulos EC, Sanchez-Perez-Grueso F, Pellise F, Nguyen JT, Wulff I, Ayamga J, Mahmud R, Hodes RM, Boachie-Adjei O; FOCOS Spine Study Group. Preoperative halo-gravity traction for severe spinal deformities at an SRS-GOP site in West Africa: protocols, complications, and results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40:153-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Garabekyan T, Hosseinzadeh P, Iwinski HJ, Muchow RD, Talwalkar VR, Walker J, Milbrandt TA. The results of preoperative halo-gravity traction in children with severe spinal deformity. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2014;23:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bumpass DB, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Stallbaumer JJ, Kim YJ, Wallendorf MJ, Min WK, Sides BA. Pulmonary function improvement after vertebral column resection for severe spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:587-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Glotzbecker M, Johnston C, Miller P, Smith J, Perez-Grueso FS, Woon R, Flynn J, Gold M, Garg S, Redding G, Cahill P, Emans J. Is there a relationship between thoracic dimensions and pulmonary function in early-onset scoliosis? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:1590-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | LaMont LE, Jo C, Molinari S, Tran D, Caine H, Brown K, Wittenbrook W, Schochet P, Johnston CE, Ramo B. Radiographic, Pulmonary, and Clinical Outcomes With Halo Gravity Traction. Spine Deform. 2019;7:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Mehta AI, Cheng J, Bagley CA, Karikari IO. Preoperative Nutritional Status is an Independent Predictor of 30-day Hospital Readmission After Elective Spine Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41:1400-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Toombs C, Lonner B, Fazal A, Boachie-Adjei O, Bastrom T, Pellise F, Ramadan M, Koptan W, ElMiligui Y, Zhu F, Qiu Y, Shufflebarger H. The Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis International Disease Severity Study: Do Operative Curve Magnitude and Complications Vary by Country? Spine Deform. 2019;7:883-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Copley LA, Pepe MD, Tan V, Sheth N, Dormans JP. A comparison of various angles of halo pin insertion in an immature skull model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1777-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Roye BD, Campbell ML, Matsumoto H, Pahys JM, Welborn MC, Sawyer J, Fletcher ND, McIntosh AL, Sturm PF, Gomez JA, Roye DP, Lenke LG, Vitale MG; Children’s Spine Study Group. Establishing Consensus on the Best Practice Guidelines for Use of Halo Gravity Traction for Pediatric Spinal Deformity. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40:e42-e48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shaw KA, Griffith M, Schmitz ML, Brahma B, Fletcher ND, Murphy JS. Application of a Halo Fixator for the Treatment of Pediatric Spinal Deformity. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2021;11:e20.00005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Park DK, Braaksma B, Hammerberg KW, Sturm P. The efficacy of preoperative halo-gravity traction in pediatric spinal deformity the effect of traction duration. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2013;26:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hwang CJ, Kim DG, Lee CS, Lee DH, Cho JH, Park JW, Baik JM, Lee KB. Preoperative Halo Traction for Severe Scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020;45:E1158-E1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Letts RM, Palakar G, Bobecko WP. Preoperative skeletal traction in scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:616-619. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Wang J, Hai Y, Han B, Zhou L, Zhang Y. Preoperative halo-gravity traction combined with one-stage posterior spinal fusion surgery following for severe rigid scoliosis with pulmonary dysfunction: a cohort study. BMC Surg. 2024;24:286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rinella A, Lenke L, Whitaker C, Kim Y, Park SS, Peelle M, Edwards C 2nd, Bridwell K. Perioperative halo-gravity traction in the treatment of severe scoliosis and kyphosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:475-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Victor DI, Bresnan MJ, Keller RB. Brain abscess complicating the use of halo traction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:635-639. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Tredwell SJ, O'Brien JP. Apophyseal joint degeneration in the cervical spine following halo-pelvic distraction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1980;5:497-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | O'Brien JP, Yau AC, Hodgson AR. Halo pelvic traction: a technic for severe spinal deformities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;179-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Popescu MB, Ulici A, Carp M, Haram O, Ionescu NS. The Use and Complications of Halo Gravity Traction in Children with Scoliosis. Children (Basel). 2022;9:1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Qian BP, Qiu Y, Wang B. Brachial plexus palsy associated with halo traction before posterior correction in severe scoliosis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006;123:538-542. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Buchowski JM, Bhatnagar R, Skaggs DL, Sponseller PD. Temporary internal distraction as an aid to correction of severe scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2035-2041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cheng X, Ma H, Tan R, Wu J, Zhou J, Zou D. Two-stage posterior-only procedures for correction of severe spinal deformities. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hu HM, Hui H, Zhang HP, Huang DG, Liu ZK, Zhao YT, He SM, Zhang XF, He BR, Hao DJ. The impact of posterior temporary internal distraction on stepwise corrective surgery for extremely severe and rigid scoliosis greater than 130°. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:557-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Grabala P, Galgano MA, Grabala M, Buchowski JM. Radiological and Pulmonary Results of Surgical Treatment of Severe Idiopathic Scoliosis Using Preoperative Halo Gravity Traction Compared with Less Invasive Temporary Internal Distraction in Staged Surgery in Adolescents. J Clin Med. 2024;13:2875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Oliveira JAA, Paiva AC, Afonso PPCC, Almeida PC, Visconti RDR, Meireles RDSP. The use of cranial halo traction versus temporary internal distraction in staged surgery for severe scoliosis: a comparative study. Coluna. 2021;20:254-259. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Caubet JF, Emans JB. Halo-gravity traction versus surgical release before implantation of expandable spinal devices: a comparison of results and complications in early-onset spinal deformity. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/