Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.109963

Revised: June 15, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 204 Days and 23.2 Hours

In this aging population, lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) reduces walking distance and impairs functionality. The definitive treatment is still controversial.

To assess the efficacy of physical therapy and surgery in improving function and reducing pain levels in patients with LSS, both in the short and long term.

This prospective study screened patients aged 50-80 years with LSS and divided them into two groups based on certain criteria: Surgical and conservative. The conservative group received a supervised physical therapy and exercise program for 45 minutes, five days a week, for one month. The surgery group underwent micro endoscopic decompression surgery based on their LSS levels. Assessments, conducted before treatment and at one-month and one-year intervals, included the participants' walking distance, pain level using the visual analog scale, func

The study comprised 40 participants, equally divided into surgical and conservative treatment groups, with no significant demographic differences. After one year, both groups exhibited similar changes in walking distance and pain levels. However, the conservative group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in sub-parameters of functional activity and symptom severity of the SSS. After one year, the surgical group showed greater func

Both treatments showed comparable efficacy in core outcomes (pain, walking distance). However, complementary advantages were observed: Conservative management demonstrated superior improvement in SSS functional subscales, while surgery yielded greater gains in daily living activities and low-back-pain-related disability.

Core Tip: Lumbar spinal stenosis is a common cause of pain and functional limitation in older adults. Surgery is frequently performed, but its long-term superiority over conservative treatments remains controversial. This study found no significant long-term difference between surgical and conservative treatments regarding pain relief, walking distance, and functionality. However, the surgical group showed greater improvements in disability scores. These findings support the use of supervised physical therapy as an effective first-line treatment, potentially reducing the need for surgery.

- Citation: Ayyildiz A, Yilmaz A, Erinç S, Aydin L, Ayyıldız H, Yilmaz F. One-year follow-up of conservative and surgical treatment results for patients diagnosed with lumbar spinal stenosis. World J Orthop 2025; 16(12): 109963

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i12/109963.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.109963

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a painful spinal disorder characterized by pain in the buttocks and lower extremities. Low back pain may also be present. It results from a lack of space for neural and vascular structures in the lumbar spine. Patients experience increased pain while walking, standing, and extending their lumbar region. However, symptoms are alleviated by lumbar flexion, sitting, and cycling[1]. Studies have found that the incidence of patients diagnosed with LSS among those with low back pain ranges from 13% to 29%[1-3]. A Framingham study of patients over 60 years old reported LSS prevalence ranging from 19% to 47%[4]. The utilization of magnetic resonance imaging has led to a recent increase in these rates[2]. Degenerative changes in the spine play a significant role in LSS development, and its prevalence increases with an aging population[1]. In this ageing population, LSS reduces walking distance and impairs functionality[1,5].

LSS is the most common indication for spinal surgery in patients aged 65 years and older[2,4,6,7]. Decompression surgery is the standard treatment for LSS patients[8]. The long-term effect of surgery on LSS remains controversial. A 2016 Cochrane study reported that surgical and conservative treatments have comparable outcomes for LSS, but the included studies had low evidence levels and heterogeneous physical therapy modalities, making definitive conclusions difficult[9].

This study aimed to examine the short- and long-term effects of physical therapy and surgery and compare their effectiveness in improving both function and pain levels.

This prospective clinical study was conducted between March 2020 and October 2023. Ethics committee approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the authors’ affiliated institutions. All patients were informed, and their written consent was obtained. This study was conducted according to the CONSORT guidelines.

The outpatient clinic of our Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department screened 62 patients based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria required participants to be 50-80 years old, have pain and neurogenic claudication for at least four weeks, have LSS confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, and have an Neurogenic Claudication caused by LSS score[10] of more than 11/19. Other causes of low back pain were excluded.

Exclusion criteria included prior lumbar surgery, physical therapy for LSS in the past three months, previous lumbar injections, inflammatory low back pain, spinal stenosis due to spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis, a history of trauma or suspected vertebral fracture. Additionally, patients with serious cardiopulmonary disease, malignancy, pregnancy, or psychiatric illness were excluded.

After screening, surgical indications such as progressive neurological deficit, unresponsiveness to conservative treatment, and cauda equina syndrome were assessed. Patients who met surgical criteria and were evaluated by a surgeon were assigned to the surgery group, while the remaining patients were assigned to the physical therapy group. The surgery group underwent decompression treatment based on their LSS levels. The surgical procedure is performed through an incision in the posterior muscles. The lamina bone is responsible for forming the posterior aspect of the spinal canal, thereby creating a roof over the spinal cord. The removal of the lamina and thickened ligament provides increased space for the nerves and facilitates the removal of osteophytes. Necessary sterilization and wound care were meticulously taken care of during and after the surgery. After the surgery, the patient was hospitalized in the ward and the wound was monitored for a while.

The physical therapy group received inpatient physical therapy and exercise. Physical therapy modalities included hot packs, therapeutic electrical neurostimulation (TENS), and ultrasound. A frequency of between 50 and 150 Hertz was preferred for TENS. This level was adjusted according to the patient's tolerance. Patients could feel the stimulation strongly yet comfortably. Hot packs and TENS were applied for 20 minutes each. Ultrasound application was performed at 1 MHz frequency and 1 W/cm² intensity. Patients followed William’s exercise protocol, supervised by a physiotherapist, aimed at strengthening lumbar flexion, preventing lumbar extension, and reinforcing abdominal and gluteal muscles. The exercise program lasted four weeks, with sessions five times per week for 45 minutes. Warm-up and cool-down phases lasted five minutes each. Patients were also given a home exercise program post-discharge. Patients were called by phone once a week to evaluate their compliance with the exercises and to give advice about continuity.

Patients were evaluated before treatment, at one month, and one year after treatment. Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, occupation, and educational status, were recorded pre-treatment. At each follow-up, patients were assessed for walking distance, pain levels with visual analog scale (VAS), and sensory deficits. Functional status was measured using the Istanbul low back pain disability index (ILBDI), Swiss Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire (SSS), and Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) Index.

Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum values, frequency, and ratio. In the power analysis, 36 patients were identified as sample size with a confidence interval of 90%. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed variable distribution. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for inde

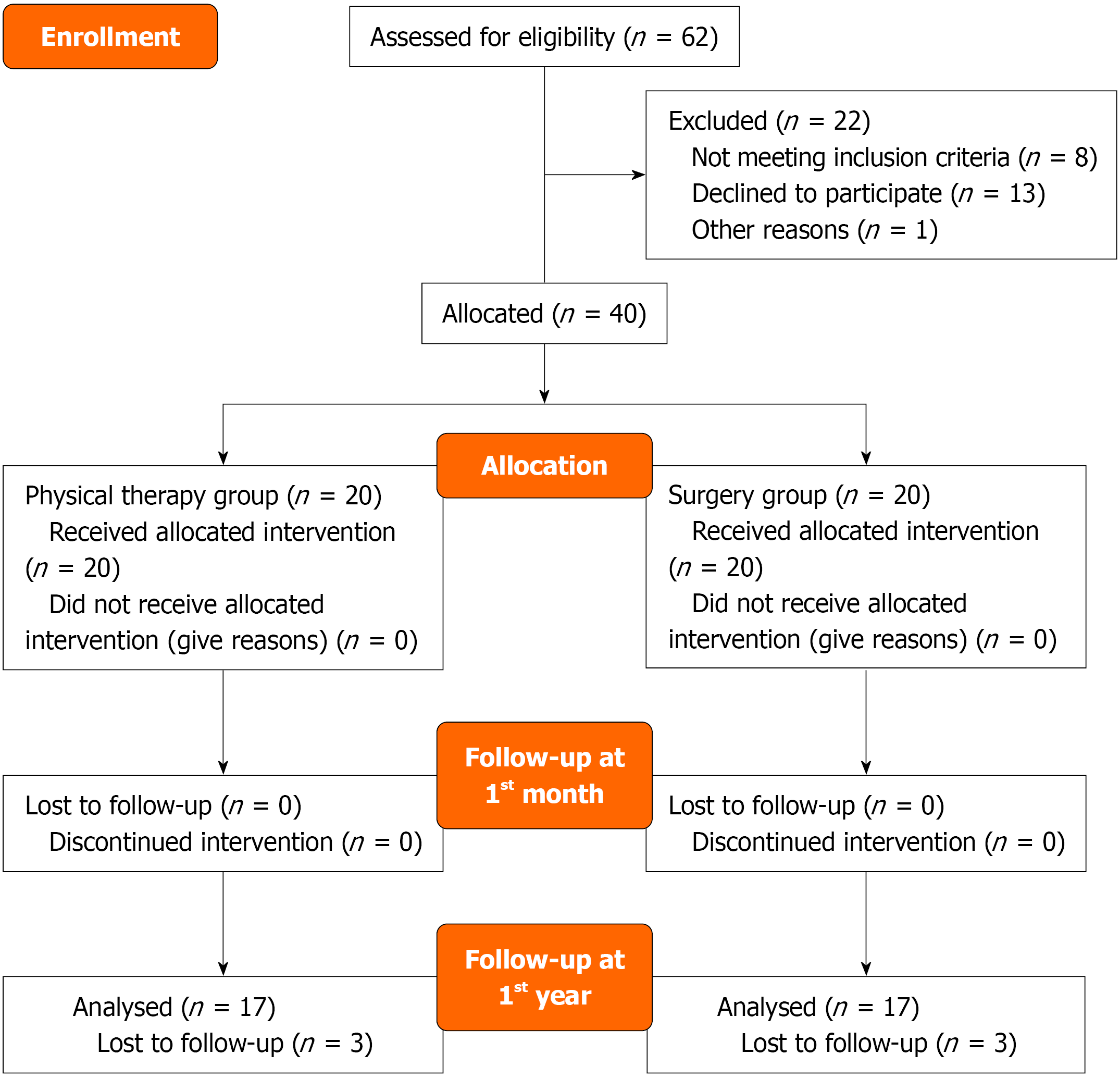

Out of 62 screened patients, 40 were included. All 40 completed the one-month follow-up, but only 34 completed the one-year follow-up (Figure 1). Demographic characteristics are detailed in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between groups regarding age, gender, education, and occupational status (P = 0.096, P = 0.074, P = 0.744 and P = 0.212, respectively).

| Min-max | Median | mean ± SD/n (%) | ||

| Age | 55.0-83.0 | 65.0 | 65.3 ± 7.21 | |

| Sex | Female | 25 (62.5) | ||

| Male | 15 (37.5) | |||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 33 (82.5) | ||

| Active worker | 7 (17.5) | |||

| Educational status | Uneducated | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Primary school | 14 (35) | |||

| Middle school | 10 (25) | |||

| High school | 12 (30) | |||

| University | 3 (7.5) | |||

| Sensory loss | (-) | 24 (60) | ||

| (+) | 16 (40) | |||

| Incontinence | (-) | 27 (67.5) | ||

| (+) | 13 (32.5) | |||

| Spinous process sensitivity | (-) | 30 (75) | ||

| (+) | 10 (25) | |||

| Paravertebral muscle spasm | (-) | 10 (25) | ||

| (+) | 30 (75) | |||

| Duration of pain | 30.0-450.0 | 150.0 | 216.1 ± 139.0 | |

| Hand-ground distance | 0.0-70.0 | 15.0 | 21.6 ± 20.9 | |

| Walking distance (m) | 10.0-600.0 | 100.0 | 143.8 ± 164.5 | |

| Visual pain score during movement | 5.0-10.0 | 8.0 | 8.1 ± 1.4 | |

| Visual pain score during resting | 0.0-8.0 | 3.5 | 3.4 ± 2.1 | |

| Visual pain score during night | 0.0-9.0 | 4.0 | 3.8 ± 2.8 | |

| ILBDI score | 11.0-81.0 | 40.0 | 40.1 ± 15.7 | |

| NEADL score | 12.0-56.0 | 31.5 | 33.4 ± 13.9 | |

| Symptom severity scale of SSS | 12.0-32.0 | 20.0 | 21.0 ± 5.4 | |

| Physical function scale of SSS | 5.0-90.0 | 10.0 | 14.5 ± 17.8 | |

The conservative group exhibited significantly lower rates of incontinence and hand-ground distance compared to the surgical group (P = 0.018). However, there were no significant differences in spinous process tenderness, paravertebral muscle spasm rates, or pain duration between groups (P = 0.144, P = 0.144 and P = 0.179, respectively) (Table 2).

| Surgery group | Conservative group | P value | ||||

| n (%) | Median | n (%) | Median | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.7 ± 6.80 | 63.5 | 67.1 ± 7.4 | 68.5 | 0.0961 | |

| Sex | Female | 12 (60.0) | 13 (55.0) | 0.0742 | ||

| Male | 8 (40.0) | 7 (35.0) | ||||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 15 (75.0) | 18 (90.0) | 0.2122 | ||

| Active worker | 5 (25.0) | 2 (10.0) | ||||

| Educational status | ||||||

| Uneducated | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.7442 | |||

| Primary school | 6 (30.0) | 8 (40.0) | ||||

| Middle school | 5 (25.0) | 5 (25.0) | ||||

| High school | 7 (35.0) | 5 (25.0) | ||||

| University | 1 (5.0) | 2 (10.0) | ||||

| Incontinence | (-) | 10 (50.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0.0182 | ||

| (+) | 10 (50.0) | 3 (15.0) | ||||

| Spinous process sensitivity | (-) | 13 (65.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0.1442 | ||

| (+) | 7 (35.0) | 3 (15.0) | ||||

| Paravertebral Muscle spasm | (-) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (35.0) | 0.1442 | ||

| (+) | 17 (85.0) | 13 (65.0) | ||||

| Duration of pain (mean ± SD) | 194.0 ± 153.3 | 120.0 | 238.3 ± 123.1 | 200.0 | 0.1791 | |

| Hand-ground distance (mean ± SD) | 32.5 ± 21.9 | 30.0 | 10.8 ± 13.1 | 6.0 | 0.0011 | |

There were no significant differences in sensory deficit rates before treatment, at one month, and one-year post-treatment within and between groups (P > 0.05). Both groups showed significant increases in walking distance at both one month and one-year post-treatment (P = 0.001 and P = 0.002), but the improvements did not significantly differ between groups (P = 0.1) (Table 3).

| Surgery group | Conservative group | P value | |||

| mean ± SD | Median | mean ± SD | Median | ||

| Walking distance (m) | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 132.5 ± 182.5 | 50.0 | 155.0 ± 148.3 | 100.0 | 0.1731 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 241.8 ± 230.7 | 150.0 | 184.5 ± 135.4 | 150.0 | 0.7431 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 349.4 ± 259.8 | 200.0 | 255.3 ± 195.8 | 150.0 | 0.2371 |

| Change compared to pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | 109.3 ± 149.4 | 50.0 | 29.5 ± 31.5 | 30.0 | 0.1001 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0012 | 0.0022 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | 200.0 ± 213.1 | 100.0 | 99.4 ± 142.1 | 50.0 | 0.2111 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0012 | 0.0042 | |||

| Visual pain score during movement | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 8.0 ± 1.1 | 8.0 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 8.0 | 0.6281 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 5.8 ± 2.6 | 6.0 | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 7.0 | 0.1161 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 5.5 ± 2.6 | 6.0 | 6.6 ± 2.2 | 7.0 | 0.2241 |

| Change compared to pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | -2.2 ± 2.5 | -1.5 | -1.1 ± 1.2 | -1.0 | 0.1891 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | -2.5 ± 2.6 | -2.0 | -1.7 ± 1.7 | -1.0 | 0.5941 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0032 | 0.0032 | |||

| Visual pain score during resting | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 3.0 | 3.9 ± 2.0 | 4.0 | 0.1851 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.5 | 3.6 ± 2.5 | 3.5 | 0.0091 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 2.6 ± 2.7 | 2.0 | 0.1031 |

| Change compared to pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | -1.7 ± 1.7 | -2.0 | -0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0121 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0072 | 0.0832 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | -1.6 ± 1.7 | -2.0 | -1.4 ± 1.7 | -1.0 | 0.8991 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0062 | 0.002 | |||

| Visual pain score during night | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 3.6 ± 2.5 | 4.0 | 4.1 ± 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.6231 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 1.5 | 3.7 ± 3.3 | 3.0 | 0.1321 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 1.2 ± 1.7 | 0.0 | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 3.0 | 0.0581 |

| Change compared to pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | -1.5 ± 2.1 | 0.0 | -0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.1501 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0112 | 0.0842 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | -1.9 ± 2.3 | 0.0 | -1.2 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.5491 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0012 | 0.012 | |||

The VAS scores with movement, at rest, and at night in the surgical group significantly decreased at 1 month and 1 year after treatment compared to pretreatment (P = 0.002 and P = 0.003; P = 0.007 and P = 0.006; P = 0.011 and P = 0.001, respectively). Similarly, in the conservative group, VAS scores during movement significantly decreased at 1 month and 1 year after treatment compared to pretreatment (P = 0.003 and P = 0.003, respectively). However, the VAS score at rest and at night in the 1st month after treatment did not show significant change compared to pretreatment in the conservative group (P = 0.083; P = 0.084, respectively). In the conservative group, there was a significant decrease in VAS scores at rest and at night in the first year after treatment compared to pretreatment (P = 0.004; P = 0.011, respectively). The decrease in VAS score at rest before and one month after treatment in the surgical group was significantly higher than in the conservative group (P = 0.012). There was no significant difference between the surgical and conservative groups in the reduction of VAS scores at rest and at night before and one year after treatment (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

There was no significant difference in ILBDI and NEADL scores between the two groups before treatment, 1 month after treatment, and 1 year after treatment (P = 0.379, P = 0.401, P = 0.73; P = 0.278, P = 0.371, P = 0.796 respectively). However, in the surgery group, there was a significant difference in ILBDI and NEADL scores at both 1 month and 1 year after treatment compared to before treatment (P = 0.001 and P = 0.001; P = 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively). A significant difference in ILBDI and NEADL values was observed in the conservative group at 1 month (P < 0.001 and P = 0.004, respectively). However, no significant difference was found at 1 year (P = 0.075 and P = 0.457, respectively). The change in NEADL scores at 1 year was significantly higher in the surgical group compared to the conservative group (P = 0.019) (Table 4).

| Surgery group | Conservative group | P value | |||

| mean ± SD | Median | mean ± SD | Median | ||

| ILBDI score | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 43.4 ± 17.4 | 42 | 36.9 ± 13.5 | 38 | 0.3791 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 34.8 ± 13.8 | 37.5 | 32.2 ± 13.5 | 34.5 | 0.4011 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 31.2 ± 12.2 | 30 | 31.4 ± 11.8 | 28 | 0.7301 |

| Change compared to Pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | -8.6 ± 11.4 | -5.5 | -4.7 ± 5.4 | -2 | 0.4291 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0012 | 0.0002 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | -10.9 ± 12.6 | -4 | -4.2 ± 8.4 | -3 | 0.1561 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0012 | 0.0752 | |||

| NEADL score | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 30.8 ± 14.1 | 25.5 | 36.0 ± 13.6 | 35 | 0.2781 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 37.0 ± 14.2 | 38.5 | 41.4 ± 13.1 | 43 | 0.3711 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 39.2 ± 13.2 | 39 | 38.5 ± 13.1 | 37 | 0.7961 |

| Change compared to pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | 6.2 ± 6.8 | 3 | 5.4 ± 7.7 | 2 | 0.5661 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0012 | 0.0042 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | 8.2 ± 7.2 | 6 | 1.4 ± 7.8 | 1 | 0.0191 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0012 | 0.4572 | |||

| Symptom severity scale of SSS | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 22.0 ± 5.4 | 22 | 20.0 ± 5.4 | 20 | 0.2381 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 17.3 ± 5.3 | 15.5 | 21.8 ± 6.6 | 21 | 0.0181 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 20.2 ± 5.7 | 20 | 10.6 ± 4.6 | 9 | 0.0011 |

| Change compared to pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | -4.7 ± 4.5 | -4 | 1.7 ± 4.1 | 0 | 0.0011 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0002 | 0.0422 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | -1.5 ± 2.9 | -1 | -8.2 ± 4.2 | -9 | 0.0011 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0632 | 0.0012 | |||

| Physical function scale of SSS | |||||

| Pre-treatment | 11.3 ± 3.2 | 11 | 10.7 ± 4.2 | 9 | 0.2211 |

| Post-treatment 1st month | 10.4 ± 5.3 | 10 | 8.4 ± 2.3 | 8 | 0.0151 |

| Post treatment 1st year | 10.8 ± 2.4 | 10 | 1.5 ± 3.3 | 0 | 0.0011 |

| Change compared to pre-treatment | |||||

| Post-treatment 1st month change | -0.8 ± 1.6 | -1 | -2.2 ± 3.2 | -1.5 | 0.2651 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.0542 | 0.0012 | |||

| Post-treatment 1st year change | -0.4 ± 2.4 | 0 | -9.3 ± 5.7 | -8 | 0.0011 |

| Intra-group change P value | 0.5122 | 0.0002 | |||

There was no significant difference in the two sub-parameters of the SSS between both groups before treatment (P = 0.238 and P = 0.221, respectively). However, in the conservative group, both sub-parameters showed a significant difference at 1 month and 1 year compared to pretreatment (P = 0.042 and P = 0.001; P = 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). In the surgical group, only the symptom severity scale of SSS showed a significant change at 1 month compared to pretreatment (P < 0.001). Significant differences were found in the symptom severity scale of SSS at both 1 month and 1 year (P = 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively) when evaluating these changes. However, significant differences were only found in the physical function scale of SSS in the 1st year (P = 0.001) (Table 4).

Although LSS is the most common indication for spinal surgery in the elderly population, studies have not yet provided high-level evidence to confirm its surgical efficacy. Consequently, the long-term efficacy of LSS treatment remains a subject of debate. In the present study, both the surgical and conservative treatment groups exhibited comparable long-term outcomes with regard to pain reduction and walking distance. While the surgical group demonstrated enhanced functionality in activities of daily living in the long term, the conservative group exhibited significant improvement, particularly in the physical activity subscale of the SSS Scale, which is specifically designed for LSS evaluation. This finding suggests that there is no clear superiority between surgical and conservative treatments for LSS in one-year follow-up.

From a mechanistic perspective, surgical and conservative treatments for LSS address different pathological contributors to symptomatology. Surgical decompression has been demonstrated to directly alleviate neural compression by removing hypertrophic ligamentum flavum, osteophytes, and lamina[11]. This process increases the diameter of the spinal canal and relieves mechanical pressure on the cauda equina and nerve roots[11,12]. This anatomical restoration can result in more immediate improvements in neurogenic claudication and daily functioning. Conversely, conservative treatment primarily targets secondary pathophysiological processes, such as muscular imbalance, altered biomechanics, and inflammation. Modalities like TENS and therapeutic ultrasound reduce pain perception via gate control theory and enhance local circulation, while flexion-based exercises improve spinal alignment and promote central canal space by reducing lumbar lordosis[13,14]. Consequently, while surgery resolves structural impingement, physical therapy may achieve functional recovery by modifying neuromuscular control, improving flexibility, and enhancing spinal stability over time[13].

The observational cohort study by Atlas et al[15] evaluated patients diagnosed with LSS who underwent either surgical or conservative treatment over a period of 8-10 years. The study concluded that the surgical group demonstrated superior outcomes in terms of leg pain and functionality when compared to the conservative group. However, both groups exhibited similar results regarding low back pain, other symptoms, and patient satisfaction. In a subsequent study, Atlas et al[16] emphasised that surgical intervention should be prioritised for cases that do not respond to non-surgical approaches. Furthermore, emphasis was placed on the significance of patient education, pain management, exercise, and physical therapy, particularly during the early stages of LSS. Similarly, Amundsen et al[17] conducted a clinical study with a 10-year follow-up, recommending conservative treatment with close monitoring. Surgical intervention was proposed exclusively for patients who had not attained long-term relief through conservative measures. Sengupta and Herkowitz[18] also advocated for the prioritisation of conservative treatment before surgery.

The findings of the present study are consistent with, and further support the conclusions of Louis-Sidney et al[19], who examined the comparative effectiveness of conservative vs surgical treatments for LSS in an Afro-Caribbean popu

Surgical treatment of LSS is frequently performed, but it may lead to muscle weakness and spinal instability due to intraoperative muscle dissection and tissue damage. A systematic review by Mo et al[20] concluded that while surgery provides faster pain relief than exercise therapy, it does not enhance joint flexibility or muscle strength. This limitation was attributed to surgical trauma to the paravertebral muscles and impaired lumbar alignment. Their evaluation of physical function using the SF-36 and Oswestry Disability Index revealed no significant superiority of surgery over exercise therapy. Wei et al[21] further noted that surgery is more effective in pain reduction, but it carries a higher risk of complications. Similarly, Macedo et al[22] reported that surgery led to greater improvements in pain and disability within the first two years but found no significant difference between surgical and conservative treatments regarding walking distance. However, like other physical therapy studies, the studies included in this review are heterogeneously distri

The SPORT study compared surgical and non-surgical interventions for LSS, reporting that surgery was superior in pain relief and functionality after a four-year follow-up. However, a heterogeneous mix of treatment protocols in the non-surgical group, including physical therapy, epidural injections, and chiropractic treatment, compromised the study's ability to determine the actual effectiveness of surgery[23]. Consequently, Minetama et al[24] suggested that supervised physical therapy and exercise may yield outcomes comparable to surgery, emphasizing that non-surgical management should be the first-line treatment, particularly for mild to moderate LSS cases, to minimize healthcare costs and complications. Our study also applied supervised physical therapy under the guidance of a physiotherapist, which we believe enhanced its effectiveness. Prior research has indicated that patients with LSS who engage in supervised physical therapy achieve greater improvements in symptom severity, physical function, walking distance, and pain relief compared to those following a home-based exercise program[25].

A Cochrane review by Zaina et al[9] comparing surgical and conservative treatments for LSS found no significant superiority of either approach in long-term follow-up. The present study found no significant differences between the two groups in terms of pain, walking distance, and overall functionality after one year. Nevertheless, the surgical group demonstrated superior long-term outcomes in the ILBDI test, which measures disability due to low back pain. The marked improvement in SSS symptom severity observed in the conservative group may be indicative of the neuro

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, the lack of randomization and blinding poses a potential source of bias. Lastly, the attrition of six patients during the follow-up period may have influenced the results. Future research should aim to include larger patient cohorts and address these methodological limitations to provide more definitive evidence on the optimal treatment approach for LSS. Additionally, we are aware that a 1-year follow-up period is relatively short to be considered long-term. It would be more appropriate to plan future studies with longer observation periods. Another limitation of our study is the choice of statistical analysis method. Although repeated-measures statistical models are well-suited for longitudinal studies with multiple time-point assessments, we opted for non-parametric tests due to our relatively small sample size and non-normally distributed data. While this approach is statistically valid, more advanced methods such as repeated-measures ANOVA or linear mixed models could provide deeper insight into within-subject changes over time in future studies with larger cohorts. The non-randomized design is a limitation, as it introduces potential selection bias. Patients electing to undergo surgery may have exhibited higher baseline symptom severity or divergent expectations in comparison to those opting for conservative therapy. In addressing this issue, a methodological approach was adopted that entailed the alignment of baseline characteristics and the implementation of non-parametric statistical methodologies, which are deemed particularly suitable for circumstances involving limited sample sizes and skewed data distributions.

The two treatments were found to demonstrate similar levels of efficacy in the primary outcomes (i.e. pain and walking distance). However, a few complementary advantages were observed: Conservative management demonstrated superior improvement in SSS functional subscales, while surgery yielded greater gains in NEADL and ILBDI. Consequently, conservative treatment should be regarded as the primary approach, as it has been demonstrated to reduce healthcare expenditures and minimize surgical complications.

| 1. | Lurie J, Tomkins-Lane C. Management of lumbar spinal stenosis. BMJ. 2016;352:h6234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jensen RK, Schiøttz-Christensen B, Skovsgaard CV, Thorvaldsen M, Mieritz RM, Andresen AK, Christensen HW, Hartvigsen J. Surgery rates for lumbar spinal stenosis in Denmark between 2002 and 2018: a registry-based study of 43,454 patients. Acta Orthop. 2022;93:488-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | ECRI Health Technology Assessment Group. Treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2001;1-5. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kalichman L, Cole R, Kim DH, Li L, Suri P, Guermazi A, Hunter DJ. Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: the Framingham Study. Spine J. 2009;9:545-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim M, Cho S, Noh Y, Goh D, Son HJ, Huh J, Kang SS, Hwang B. Changes in pain scores and walking distance after epidural steroid injection in patients with lumbar central spinal stenosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI, Kreuter W, Goodman DC, Jarvik JG. Trends, major medical complications, and charges associated with surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:1259-1265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1141] [Cited by in RCA: 1114] [Article Influence: 69.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Katz JN, Harris MB. Clinical practice. Lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:818-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Suzuki A, Nakamura H. Microendoscopic Lumbar Posterior Decompression Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zaina F, Tomkins-Lane C, Carragee E, Negrini S. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD010264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Genevay S, Courvoisier DS, Konstantinou K, Kovacs FM, Marty M, Rainville J, Norberg M, Kaux JF, Cha TD, Katz JN, Atlas SJ. Clinical classification criteria for neurogenic claudication caused by lumbar spinal stenosis. The N-CLASS criteria. Spine J. 2018;18:941-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Uri O, Alfandari L, Folman Y, Keren A, Smith W, Paz I, Behrbalk E. Acute disc herniation following surgical decompression of lumbar spinal stenosis: a retrospective comparison of mini-open and minimally invasive techniques. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18:974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Andersen MØ, Carreon LY, Hummel S, Smith EC, Andresen AK. Spinal decompression improves walking capacity in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Brain Spine. 2025;5:104268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Temporiti F, Ferrari S, Kieser M, Gatti R. Efficacy and characteristics of physiotherapy interventions in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2022;31:1370-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ammendolia C, Côté P, Rampersaud YR, Southerst D, Schneider M, Ahmed A, Bombardier C, Hawker G, Budgell B. Effect of active TENS versus de-tuned TENS on walking capacity in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized controlled trial. Chiropr Man Therap. 2019;27:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, Deyo RA, Singer DE. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: 8 to 10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:936-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 430] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Atlas SJ, Delitto A. Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:198-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Amundsen T, Weber H, Nordal HJ, Magnaes B, Abdelnoor M, Lilleâs F. Lumbar spinal stenosis: conservative or surgical management?: A prospective 10-year study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1424-35; discussion 1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sengupta DK, Herkowitz HN. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Treatment strategies and indications for surgery. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:281-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Louis-Sidney F, Duby JF, Signate A, Arfi S, De Bandt M, Suzon B, Cabre P. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Treatment: Is Surgery Better than Non-Surgical Treatments in Afro-Descendant Populations? Biomedicines. 2022;10:3144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mo Z, Zhang R, Chang M, Tang S. Exercise therapy versus surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34:879-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wei FL, Zhou CP, Liu R, Zhu KL, Du MR, Gao HR, Wu SD, Sun LL, Yan XD, Liu Y, Qian JX. Management for lumbar spinal stenosis: A network meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Surg. 2021;85:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Macedo LG, Hum A, Kuleba L, Mo J, Truong L, Yeung M, Battié MC. Physical therapy interventions for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2013;93:1646-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson A, Blood E, Herkowitz H, Cammisa F, Albert T, Boden SD, Hilibrand A, Goldberg H, Berven S, An H. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:1329-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Minetama M, Kawakami M, Teraguchi M, Enyo Y, Nakagawa M, Yamamoto Y, Matsuo S, Nakatani T, Sakon N, Nakagawa Y. Supervised physical therapy versus surgery for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a propensity score-matched analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Minetama M, Kawakami M, Teraguchi M, Kagotani R, Mera Y, Sumiya T, Nakagawa M, Yamamoto Y, Matsuo S, Koike Y, Sakon N, Nakatani T, Kitano T, Nakagawa Y. Supervised physical therapy vs. home exercise for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2019;19:1310-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | McGregor AH, Probyn K, Cro S, Doré CJ, Burton AK, Balagué F, Pincus T, Fairbank J. Rehabilitation following surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. A Cochrane review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:1044-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/