Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.102402

Revised: April 23, 2025

Accepted: November 14, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 426 Days and 22.4 Hours

Femur fractures are one of the most serious injuries that occur in the older po

To evaluate the effectiveness of ultrasound (US)-guided FNB in managing preo

This retrospective cohort study included 1577 patients suffering from neck femur fractures. 387 patients were treated with a FNB for pain management upon arrival at the emergency department, the rest were treated with standard analgesia. Pain was assessed from electronic medical records using the visual analogue scale (VAS) pre surgery, 12- and 24-hour post-surgery. To determine morbidity and mortality during hospitalizations and 6 months after, it was collected from ele

In a cohort of 1577 patients, those receiving US-guided FNB had significantly lower preoperative VAS pain scores (1.46 ± 2.49 vs 1.82 ± 2.59, P = 0.001), reduced rehospitalization rates (0.99 ± 1.96 vs 1.46 ± 2.34, P < 0.001), and lower mortality (16% vs 32%, P < 0.001) compared to standard analgesia.

US guided FNB is more effective for pain management compared with standard analgesia. This method was also found to significantly reduce the risk of morbidity in those patients.

Core Tip: We found that ultrasound (US) guided femoral nerve block (FNB) is a safe and effective method to assist in pain management prior to surgery in hip fractures. This method is beneficial in decreasing the risk of morbidity in hip fracture patients as seen in lower rates of rehospitalizations and decreased mortality. We have learned that US guided FNB led to statistically significant lower pain levels prior to surgery compared with the group that received standard analgesia. We have learned that US guided FNB resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the risk of morbidity, specifically a decrease in rehospitalization and mortality 6 months post-surgery. In the future we need to continue to research this area regarding the issue of Being able to ascertain if delirium is decreased in patients undergoing US guided FNB for pain management and if patients had a reduced need for opioids.

- Citation: Klassov Y. Ultrasound guided femoral nerve blocks as a compulsory pain protocol in femoral neck fractures. World J Orthop 2025; 16(12): 102402

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i12/102402.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.102402

Hip and femur fractures are common in patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) and remain one of the most serious injuries that occur in the older population[1]. The mean age of these patients is 81 years and 75% are female[2]. A significant proportion of hip fracture survivors have decreased ability to perform activities of daily living. About half do not regain their pre-fracture functional status, and 10%-20% of those admitted from home require long-term institutional care[3]. Postoperative Mortality in hip fractures is 5%-10% at 30 days and 19%-33% at 1 year[4].

Hip fractures result in severe pain and pain management is often a challenge due to the advanced age, comorbidities, and increased sensitivity to side effects from systemic analgesics in this population[1]. Pain has been shown to be associated with increased production of pro inflammatory cytokines[5], neuro-hormonal stress response, tachycardia, myocardial ischemia, and delayed mobilization, all of which may increase postoperative length of stay and are associated with increased postoperative mortality[2,6].

Under treatment for pain as well as opiate analgesic use in these patients puts them at a higher risk to develop delirium[1], and it’s been demonstrated that delirium can increase mortality risk in elder patients admitted to the intensive care unit[7]. Standard care systemic analgesia includes paracetamol which is usually insufficient to control severe pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug are often contraindicated in this population due to drug-drug interactions and risks of side effects. Opioids are widely used but may be ineffective for pain on movement. Furthermore, their use is associated with potentially serious side effects such as confusion, nausea and constipation[1,3]. Several studies have demonstrated that regional blockades improved pain control, decreased analgesic requirements, and decreased time to first mobili

In a study conducted by Luger et al[9] found that for preoperative acute pain management in elderly patients with hip fractures, regional anesthesia appeared to be superior to systemic pain therapy as seen in the: Pain scores, less additional analgesics and an increase in the troponin T levels in the group treated only with systemic analgesia. Despite the evidence many institutions face difficulties when implementing femoral nerve blocks (FNB) protocols as seen in the following studies: Holdgate et al[10] revealed that of 36 ED in Australia, in patients who presented with a hip fracture, only 7% received an FNB. Mittal and Vermani[11] conducted a national survey in the United Kingdom and found that 74% of the United Kingdom EDs contacted had ultrasound (US) access, but only 10% regularly administered US guided FNBs. This retrospective study intended to establish if FNB should become a routine procedure for pain management in neck of femur fractures instead of the usual analgesic protocol involving opioids. We compared the pain levels and morbidity between patients who had undergone US guided FNB and patients managed with the standard analgesia protocol.

This Retrospective cohort study was approved by the Soroka Medical Center Helsinki Committee. All of the patients identifying information was encoded.

This study was conducted at Soroka Medical center in Beer Sheva, Israel. Patients admitted to Soroka Medical Center ED with femoral neck fractures between the years 2015-2018 were eligible for the study. Inclusion criteria were adults older than 18 years, all sexes and all types of femoral neck fractures as well as bilateral neck of femur fractures. Exclusion criteria were other injuries to the same limb that would interfere with rehabilitation or outcome, open or closed fractures that occurred more the 7 days prior to surgery, Nonunion fractures, Pathologic fracture, Periprosthetic fracture, Associated Spinal injury and non-ambulatory patients. The Data for this study was collected retrospectively from the patient’s electronical medical records using the databases “Chameleon, “Metavision” and “OFEK”.

The FNB intervention was performed by emergency staff physicians and resident physicians upon arrival at the ED. Those staff members had to follow a build in protocol to ensure that the treatment that every patient had was consistent. With the patient in the supine position, the skin over the femoral crease is disinfected and the sterile cover coated transducer is positioned transversely on the inguinal crease to identify the femoral blood vessels, fascia lata, fasica iliaca and femoral nerve. A skin wheal of local anesthetic ais made on the lateral aspect of the thigh about 1 cm away from the lateral edge of the transducer. The echogenic prepared 22G needle is then inserted in plane in a lateral to medial orientation and advanced toward the femoral nerve. Once the needle tip is witnessed close to the nerve and after careful aspiration, 1 to 2 mL of local anesthetic is injected to confirm the proper needle placement by a witnessed spread around the femoral nerve. After confirmation of needle placement, the total amount of 15-20 mL of 1% lidocaine and 15-20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine was injected. The total amount of anesthetic was calculated not to exceed the maximal body weight correlated dose. In patients without contraindications like unbalanced diabetes mellitus or arterial hypertension 10 mg of dexamethasone were added.

The primary outcome was to find if there was a significant difference in pain scores in patients treated with FNB compared with patients treated with the standard analgesia protocol. Pain was assessed from electronic medical records using the visual analogue scale (VAS) pre surgery, 12- and 24-hours post-surgery.

The secondary outcome was to find if there was a significant difference in morbidity in patients treated with FNB compared with patients treated with the standard analgesia protocol. Morbidity was a binary parameter and patients were classified as positive for morbidity if a diagnoses stroke, sepsis, rehospitalization or mortality were found in the patient’s electronical medical records during and hospitalization 6 months after it.

Formal statistical analysis plan was developed for each proposed analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, all statistical analyses were performed on a per-subject basis. Descriptive statistics are provided using summary tables. The statistics for continuous normal distribution variables include mean and standard deviation. Continuous variables that are not normally distributed include median and interquartile range. Categorical variables are described with numbers and percentages. The method of analyses for continuous variables were parametric using t test. Parametric model assump

First, we evaluate the association between morbidity and US guided FNB adjusted for other independent variables using multivariate Logistic regression.

Second, the association between pre procedure VAS and US guided FNB adjusted for other independent variables were analyzed using multivariate Poisson regression.

Statistical analysis will be performed using R-studio [RStudio Team (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/].

A total of 1577 patients were included in the study after inclusion and exclusion criteria. 387 patients received US guided FNB prior to surgery and 1190 received the standard analgesia protocol. The demographics of the two groups were similar with 64% and 65% females respectively. There was a significant difference in the mean age between the groups, 80 (SD ± 11) in the FNB group and 75 (SD ± 15) in the standard analgesia group.

The mean body mass index in both groups was 25.5 (SD ± 4.7) and the majority of the patients had an ASA score of 2, 57% and 55% respectively. The length of hospitalization was similar as well in both groups with a mean of 16 days (SD ± 13) in the FNB group and 15 (SD ± 14) days in the standard analgesia group.

The mean time to surgery in both groups was under 48 hours after admission as per our hospitals protocol. In

Regarding medical background the groups were comparable: In the FNB group 1% had a diagnosis of cerebrovascular accident (CVA), 24% had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and 18% had a diagnosis of ischemic heart disease (IHD). In the standard analgesia group 1.4% had a diagnosis of CVA, 21% had a diagnosis of DM and 21% had a diagnosis of IHD (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 1577) | Standard analgesia protoco (n = 1190) | US guided femoral nerve block (n = 387) | P value1 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 76 (15) | 75 (15) | 80 (11) | < 0.001 |

| Gender, n/N (%) | 0.7 | |||

| Female | 1016/1577 (64) | 770/1190 (65) | 246/387 (64) | |

| Male | 561/1577 (36) | 420/1190 (35) | 141/387 (36) | |

| ASA score, n/N (%) | 0.6 | |||

| 1 | 38/1045 (3.6) | 32/776 (4.1) | 6/269 (2.2) | |

| 2 | 579/1045 (55) | 427/776 (55) | 152/269 (57) | |

| 3 | 377/1045 (36) | 279/776 (36) | 98/269 (36) | |

| 4 | 51/1045 (4.9) | 38/776 (4.9) | 13/269 (4.8) | |

| Unknown | 532 | 414 | 118 | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25.5 (4.7) | 25.5 (4.7) | 25.5 (4.7) | 0.8 |

| CVA, n/N (%) | 21/1577 (1.3) | 17/1190 (1.4) | 4/387 (1.0) | 0.7 |

| T2DM, n/N (%) | 343/1577 (22) | 250/1190 (21) | 93/387 (24) | 0.2 |

| IHD, n/N (%) | 315/1577 (20) | 244/1190 (21) | 71/387 (18) | 0.4 |

| Intra capsular fracture, n/N (%) | 9/1577 (0.6) | 7/1190 (0.6) | 2/387 (0.5) | > 0.9 |

| Extra capsular fracture, n/N (%) | 220/1577 (14) | 154/1190 (13) | 66/387 (17) | 0.052 |

| Time to surgery (hours), mean (SD) | 38 (60) | 39 (68) | 32 (22) | 0.0218 |

| Hospitalization days (days), mean (SD) | 15 (14) | 15 (14) | 16 (13) | 0.3 |

When measuring pain prior to the surgery, VAS levels were significantly lower in the group that received FNB vs the group that received standard analgesia, 1.46 (SD ± 2.490) and 1.82 (SD ± 2.59) respectively as seen in Table 2.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 1577) | Standard analgesia protoco (n = 1190) | US guided femoral nerve block (n = 387) | P value1 |

| Pre surgery VAS score, mean (SD) | 1.73 (2.57) | 1.82 (2.59) | 1.46 (2.49) | 0.001 |

| 12 hours post-surgery VAS score, mean (SD) | 0.70 (1.61) | 0.68 (1.57) | 0.75 (1.73) | 0.3 |

| 24 hours post surgery VAS score, mean (SD) | 0.81 (1.60) | 0.81 (1.55) | 0.83 (1.74) | 0.058 |

| Stroke, n/N (%) | 235/1577 (15) | 184/1190 (15) | 51/387 (13) | 0.3 |

| Sepsis, n/N (%) | 19/1577 (1.2) | 16/1190 (1.3) | 3/387 (0.8) | 0.6 |

| Re hospitalization times, mean (SD) | 1.35 (2.26) | 1.46 (2.34) | 0.99 (1.96) | < 0.001 |

| Mortality, n/N (%) | 439/1577 (28) | 376/1190 (32) | 63/387 (16) | < 0.001 |

No significant decrease in pain levels were seen in the post-surgery measurements in the group that received US guided FNB when compared with the group that received standard analgesia.

When comparing VAS levels 12 hours post-surgery, the mean VAS was slightly higher in the group that received FNB 0.75 (SD ± 1.73) vs 0.68 (SD ± 1.57) in the standard analgesia group, these results were not significant.

When comparing VAS levels 24 hours post-surgery the mean VAS was slightly higher in the group that received FNB, 0.83 (SD ± 1.74) vs a mean VAS of 0.81 (SD ± 1.55) in the group that received standard analgesia, these results were not significant.

After adjusting for other independent variables, the association between lower pre surgery VAS levels and US guided FNB was found to be significant with a 15% decrease in VAS levels in the group that received a FNB as seen in Table 3.

| Predictors | Pre-surgery VAS | ||

| Incidence rate ratios | 95%CI | P value | |

| US guided femoral nerve block | 0.85 | 0.76-0.95 | 0.006 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.99-1.00 | < 0.001 |

| ASA score | 0.88 | 0.81-0.95 | 0.002 |

| Extra capsular fracture | 0.82 | 0.71-0.95 | 0.007 |

| IHD | 1.21 | 1.07-1.36 | 0.003 |

Patients were considered to be suffering from morbidity if they were diagnosed with stroke, sepsis, rehospitalization or death in the 6 months period post-surgery.

In the univariate analysis the rates for sepsis and stroke were not significantly lower in the group that received US guided FNB.

However, the rates for rehospitalization and mortality were significantly lower in the FNB group, a mean of 0.99 (SD ± 1.96) of rehospitalizations vs 1.46 (SD ± 2.34) rehospitalizations in the standard analgesia group and 16% mortality in the FNB group vs 32% mortality in the standard analgesia group.

When dividing the study population into a group that suffered from morbidity and a non-morbidity group, the percentage of patients that received FNB were significantly higher in the non-morbidity group, 30% vs 21% in the morbidity group (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 1577) | Non-morbidity group (n = 572) | Morbidity group, (n = 1005) | P value1 |

| US guided femoral nerve block, n/N (%) | 387/1577 (25) | 174/572 (30) | 213/1005 (21) | < 0.001 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 76 (15) | 72 (17) | 79 (13) | < 0.001 |

| Gender, n/N (%) | 0.4 | |||

| Female | 1016/1577 (64) | 377/572 (66) | 639/1005 (64) | |

| Male | 561/1577 (36) | 195/572 (34) | 366/1005 (36) | |

| ASA score, n/N (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 38/1045 (3.6) | 27/395 (6.8) | 11/650 (1.7) | |

| 2 | 579/1045 (55) | 268/395 (68) | 311/650 (48) | |

| 3 | 377/1045 (36) | 96/395 (24) | 281/650 (43) | |

| 4 | 51/1045 (4.9) | 4/395 (1.0) | 47/650 (7.2) | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25.5 (4.7) | 25.3 (4.4) | 25.5 (4.8) | 0.5 |

| CVA, n/N (%) | 21/1577 (1.3) | 3/572 (0.5) | 18/1005 (1.8) | 0.060 |

| T2DM, n/N (%) | 343/1577 (22) | 83/572 (15) | 260/1005 (26) | < 0.001 |

| IHD, n/N (%) | 315/1577 (20) | 64/572 (11) | 251/1005 (25) | < 0.001 |

| Intra capsular fracture, n/N (%) | 9/1577 (0.6) | 3/572 (0.5) | 6/1005 (0.6) | > 0.9 |

| Extra capsular fracture, n/N (%) | 220/1577 (14) | 89/572 (16) | 131/1005 (13) | 0.2 |

| Time to surgery (hours), mean (SD) | 38 (60) | 36 (73) | 39 (52) | 0.3 |

| Hospitalization days (days), mean (SD) | 15 (14) | 13 (11) | 16 (14) | < 0.001 |

Other independent variables that were found to have a significant association with the non-morbidity group were lower age, higher percentage of population with a lower ASA score, less patients with DM, less patients with IHD, and a shorter hospitalization period (Table 4).

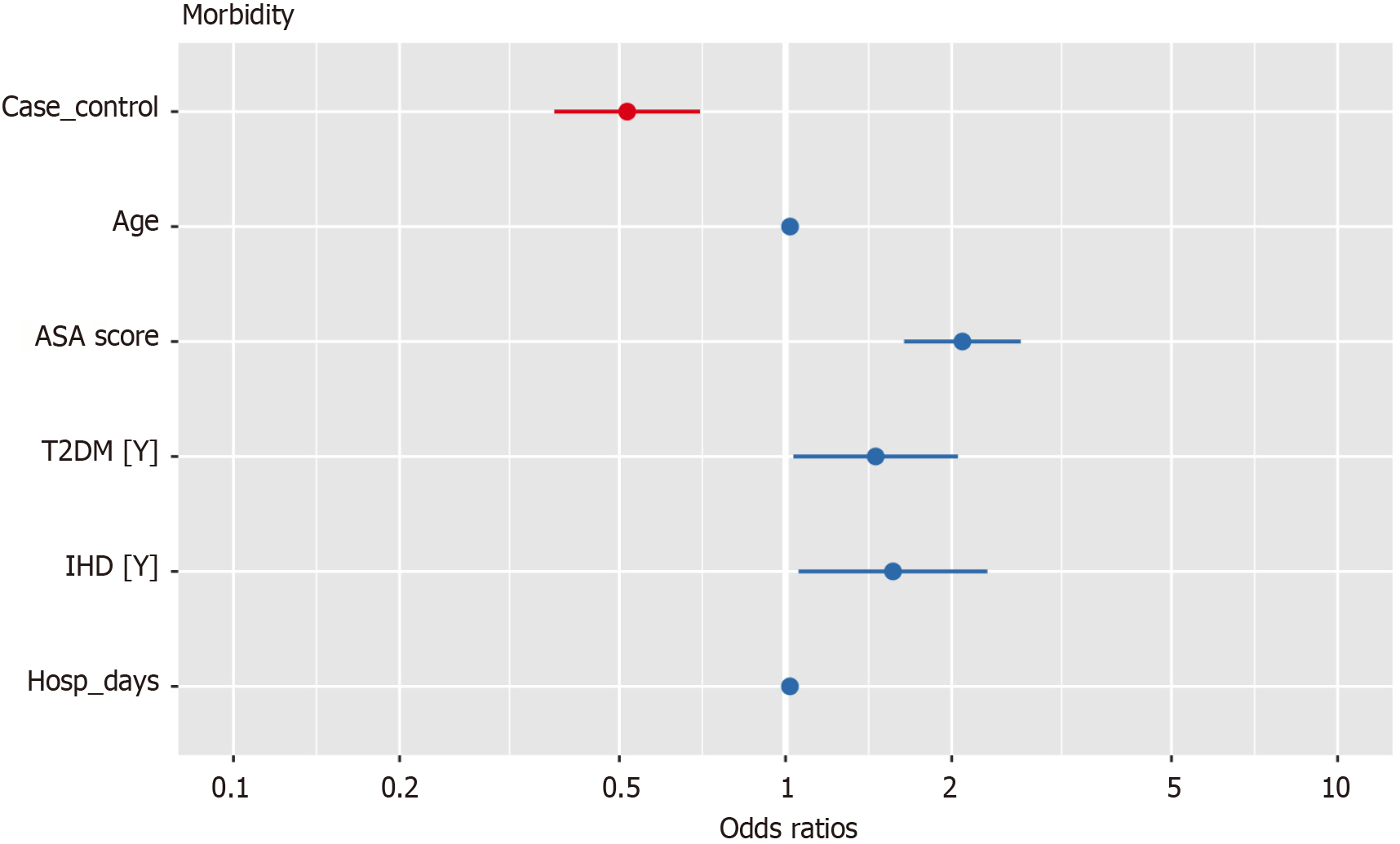

When adjusting for other independent variables the risk of morbidity was significantly lower in the US guided FNB group (OR: 0.52, 95%CI: 0.38-0.70) (Table 5).

| Predictors | Morbidity | ||

| Odds ratios | 95%CI | P value | |

| US guided femoral nerve block | 0.52 | 0.38-0.70 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01-1.03 | < 0.001 |

| ASA score | 2.09 | 1.64-2.68 | < 0.001 |

| T2DM | 1.46 | 1.04-2.06 | 0.032 |

| IHD | 1.57 | 1.06-2.34 | 0.026 |

| Hospitalization days | 1.02 | 1.01-1.03 | 0.002 |

As can be expected the risk of morbidity was significantly higher in older patients, patients with a higher ASA score, patients that have DM or IHD and in longer periods of hospitalizations (Figure 1).

Pain management in hip fractures is crucial for improved outcomes and a faster recovery. Insufficient treatment for pain leads to increased hospital length of stay, delayed ambulation, and long-term functional impairment[6].

In this study we found that US guided FNB led to statistically significant lower pain levels prior to surgery compared with the group that received standard analgesia. Although these results match our hypothesis, from our clinical experience we expected a higher mean VAS in the standard analgesia group prior to surgery.

The mean VAS score in the standard analgesia group was lower than we expected (a mean of 1.82) resulting in a small albeit significant difference in the mean VAS prior to surgery between the two groups. In previous studies the pain scales used vary as well as the reported pain levels found in both the study as well as the control group. For example, In Beaudoin et al[12] pain was measured using the NRS pain scale. 4 hours after intervention mean pain levels were 8 in the control group. In Foss et al[13] the median pain levels in the control group were 2 an hour after intervention using the VRS pain scale. These two examples show the wide variety in pain levels recorded in studies such as this.

Due to the fact this is a retrospective study that is based on electronic databases it is possible there was a human or technical error leading to a lower mean VAS than expected in the standard analgesia group. Performing a prospective study would rectify the possible errors made and provide more precise mean VAS levels.

Despite the smaller than expected difference in VAS levels between the groups our results remained significant after adjusting for other independent variables. Previous studies demonstrate the effectiveness of FNB compared with standard analgesia. For example, a Cochrane review by Guay et al[14] shows an approximate decrease of 2.5 out of 10 in pain levels on movement within 30 minutes after block placement. Our results continue to establish the effectiveness of FNB in hip fractures as seen previously.

We did not find a statistically significant difference in pain levels post-surgery when compared with the standard analgesia group. These results are expected since the analgesia provided after a regional block with 0.5% bupivacaine is expected to last 6-30 hours[15]. The policy in our hospital regarding patients with neck of femur fractures without contraindications is that they undergo surgery within 48 hours, thus it’s not expected that the analgesia from a FNB would continue to work post-surgery. If the FNB were to be repeated closer to surgery it is possible we would see an effect on post-surgical pain levels as was seen in Huh et al[16].

In this study we also found that US guided FNB resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the risk of morbidity, specifically a decrease in rehospitalization and mortality 6 months post-surgery.

Firstly, this is an important finding since other studies have found that FNBs may reduce morbidity but in these studies morbidity consisted of patients suffering from pneumonia and delirium as seen in Guay et al[14]. Interestingly, the mean age in the group that received US guided FNB was 80, 5 years older than the group that received standard analgesia (75). This finding suggests that the population in this group would be at a higher risk for morbidity due to their older age, which further strengthens our results that performing US guided FNB may reduce morbidity in patients with neck of femur fractures compared with using the standard analgesia protocol. Another significant difference between the two groups was the time to surgery. In the FNB group the time to surgery was a mean of 32 hours vs 39 hours in the standard analgesia group. Although it seems this could be a confounding factor and affect the lowered risk for mortality, this is not likely since all patients underwent surgery within the 48-hour period required by our hospital. Also, these results were taken in to account in the statistical analysis and were not found to affect the lowered morbidity found in the FNB group.

Secondly, it’s important to note that other studies did not find that FNBs had an effect on 6 month and 1 year mortality[14,17]. These discrepancies can be settled by future prospective studies examining morbidity and mortality after FNBs in hip fractures.

A primary strength of this study is that it’s based on one of the largest cohorts of hip fracture patients treated with FNB for pain management upon arrival at the ED (387 patients). This large cohort was compared to a large control group consisting of 1190 patients. The large sample size of this study strengthens the validity of our results.

Another important strength is that most of the demographic characteristics were similar reinforcing the comparability of the two groups. Also, in Israel patient’s medical files in hospitals as well as in the community are computerized. The data for this study was extracted from these files thus information regarding mortality and other diagnoses are validated and updated.

Firstly, the retrospective design of the study limits the ability to control for potential biases. The results of this study may be further ascertained by a randomized, double blinded study. Secondly, the information regarding patients’ VAS scores are based on their hospital records. It is possible there was some human or technical error in logging in VAS values leading to a lower-than-expected mean VAS in the standard analgesia group. Thirdly, this study lacked information regarding the possible reduction in opioid use after FNBs and the risk for developing delirium. We were unable to collect enough information regarding patients diagnosed with delirium during their hospitalizations. Being able to ascertain if delirium is decreased in patients undergoing US guided FNB for pain management and if patients had a reduced need for opioids would strengthen the other evidence, we have found regarding the benefits of FNBs.

Our results further support previous studies and suggest that US guided FNB is a safe and effective method to assist in pain management prior to surgery in hip fractures. Our results also show this method is beneficial in decreasing the risk of morbidity in hip fracture patients as seen in lower rates of rehospitalizations and decreased mortality.

| 1. | Ritcey B, Pageau P, Woo MY, Perry JJ. Regional Nerve Blocks For Hip and Femoral Neck Fractures in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. CJEM. 2016;18:37-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sahota O, Rowlands M, Bradley J, Van de Walt G, Bedforth N, Armstrong S, Moppett I. Femoral nerve block Intervention in Neck of Femur fracture (FINOF): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rowlands M, Walt GV, Bradley J, Mannings A, Armstrong S, Bedforth N, Moppett IK, Sahota O. Femoral Nerve Block Intervention in Neck of Femur Fracture (FINOF): a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wiles MD, Moran CG, Sahota O, Moppett IK. Nottingham Hip Fracture Score as a predictor of one year mortality in patients undergoing surgical repair of fractured neck of femur. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:501-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Beilin B, Bessler H, Mayburd E, Smirnov G, Dekel A, Yardeni I, Shavit Y. Effects of preemptive analgesia on pain and cytokine production in the postoperative period. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morrison SR, Magaziner J, McLaughlin MA, Orosz G, Silberzweig SB, Koval KJ, Siu AL. The impact of post-operative pain on outcomes following hip fracture. Pain. 2003;103:303-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bates J, Rhodes SM, Amini R. Ultrasound Guided Femoral Nerve Blocks and the Management of Elder Patients with Hip Fractures. J Hosp Med Mana. 2015;1-4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Guay J, Parker MJ, Griffiths R, Kopp S. Peripheral nerve blocks for hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD001159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Luger TJ, Kammerlander C, Benz M, Luger MF, Garoscio I. Peridural Anesthesia or Ultrasound-Guided Continuous 3-in-1 Block: Which Is Indicated for Analgesia in Very Elderly Patients With Hip Fracture in the Emergency Department? Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2012;3:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Holdgate A, Shepherd SA, Huckson S. Patterns of analgesia for fractured neck of femur in Australian emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas. 2010;22:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mittal R, Vermani E. Femoral nerve blocks in fractures of femur: variation in the current UK practice and a review of the literature. Emerg Med J. 2014;31:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Beaudoin FL, Haran JP, Liebmann O. A comparison of ultrasound-guided three-in-one femoral nerve block versus parenteral opioids alone for analgesia in emergency department patients with hip fractures: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Foss NB, Kristensen BB, Bundgaard M, Bak M, Heiring C, Virkelyst C, Hougaard S, Kehlet H. Fascia iliaca compartment blockade for acute pain control in hip fracture patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:773-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guay J, Kopp S. Peripheral nerve blocks for hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11:CD001159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hadzic A, Carrea A, Clark TB, Gadsen J, Karmakar MK, Sala-Blanch X, Vandepitte CFM, Xu D. Hadzic’s Peripheral Nerve Blocks and Anatomy for Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia (New York School of Regional Anesthesia). 2nd ed. McGraw Hill Education/Medical, 2012: 95. |

| 16. | Huh JW, Park MJ, Lee WM, Lee DH. Effectiveness of Ultrasound-guided Single-injection Triple Nerve Block Before Cementless Bipolar Hip Hemiarthroplasty in Femoral Neck Fractures. Hip Pelvis. 2020;32:142-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Polischuk MD, Kattar N, Rajesh A, Gergis T, King K, Sriselvakumar S, Shelfoon C, Lynch G, Campbell K, Cooke C. Emergency Department Femoral Nerve Blocks and 1-Year Mortality in Fragility Hip Fractures. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2019;10:2151459319893894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/