Published online Dec 18, 2024. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v15.i12.1124

Revised: October 8, 2024

Accepted: November 12, 2024

Published online: December 18, 2024

Processing time: 141 Days and 16.1 Hours

The Johnson and Johnson faulty hip implant case represents one of the most si

Core Tip: This study provides a comprehensive examination of regulatory inadequacies within India’s medical device sector, focusing exclusively on the Johnson & Johnson hip implant case. It identifies critical deficiencies in the existing legislative framework, insufficient postmarket surveillance, and a lack of effective accountability mechanisms, all of which pose substantial risks to patient safety. The findings underscore the urgent need for systematic reforms, including the im

- Citation: Menon V. Regulatory gaps in India’s medical device framework: The case of Johnson and Johnson’s faulty hip implants. World J Orthop 2024; 15(12): 1124-1134

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v15/i12/1124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v15.i12.1124

In the dynamic landscape of modern healthcare technologies and solutions, the regulation of medical devices represents the cornerstone for ensuring patient safety, treatment efficacy and public health integrity. From traditional medical implants such as stents, heart valves, breast implants, and artificial joints to Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence-enabled healthcare devices, medical devices have undergone significant evolution and enhancement. Lifesaving medical implants and state-of-the-art medical diagnostic tools represent a broad spectrum of medical devices, each with a unique set of risks and benefits, thereby highlighting the need for regulatory oversight. Effective regulations ensure that medical devices meet minimum safety standards, undergo rigorous testing, and adhere to quality control measures throughout their lifecycle. As technological advancements continue to accelerate, the regulatory landscape must evolve in tandem to address emerging challenges such as cybersecurity threats and ethical considerations.

Against the backdrop of ongoing innovations in the healthcare sector and the imperative for regulatory scrutiny, this paper explores the case of faulty Johnson & Johnson (J&J) hip implants. It chronicles the significant sequence of events from product rollout to the high rate of device failure, culminating in global product recall and widespread victim compensation settlements. Delayed reactions from both the company and Indian regulatory authorities underscore the urgent need for improved oversight.

In light of these observations, this study is guided by the following hypotheses.

The regulatory framework for medical devices in India inadequately addresses emerging risks owing to insufficient postmarket surveillance and lenient approval processes, allowing unsafe products to enter the market without rigorous evaluation.

Shortcomings in regulatory oversight lead to delays in addressing adverse events and impede effective tracking of affected patients, exacerbating the challenges faced by victims.

The J&J hip implant case serves as a critical reminder of the vulnerabilities within India’s medical device regulatory landscape. Despite the introduction of the Medical Devices Rules in 2017, significant loopholes persist, putting patients at risk and increasing reliance on foreign manufacturers.

This study adopts a qualitative case study approach to investigate the J&J faulty hip implant incident, exploring the complex relationships among regulatory frameworks, patient outcomes, and procedural failures that contributed to the crisis. The analysis is based on an extensive review of relevant documents and reports, focusing on key legal frameworks such as the Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940 and the Medical Devices Rules of 2017. Public notices issued by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) are also scrutinized to assess the regulatory response to the incident.

Insights are further drawn from reports by expert committees established by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), including a committee tasked with investigating faulty articular surface replacement (ASR) hip implants and another focused on formulating a compensation model for affected patients. Judicial proceedings, such as the Delhi High Court orders mandating compensation from J&J and the Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed in the Supreme Court, are reviewed to highlight legal efforts to address the issue. This study also considers the Supreme Court’s acceptance of the central compensation scheme for patients who underwent revision surgeries, providing a comprehensive legal and regulatory perspective on the incident.

To capture patient experiences, testimonials from ASR faulty hip implant patients submitted to the expert committee were analyzed, offering firsthand accounts of the incident's impact. Relevant newspaper reports and scholarly articles from reputable journals, such as the British Medical Journal and the National Institutes of Health, were included to contextualize the incident within broader medical and public discourse. Finally, concerns regarding metal-on-metal hip implants documented by the United States FDA are reviewed, along with guidance and resources from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of Australia. Collectively, these sources provide a robust foundation for a thorough analysis of the regulatory, legal, and patient care dimensions of the J&J hip implant incident.

Deputy International Limited (DePuy), a United Kingdom subsidiary of Johnson and Johnson, developed a hip re

DePuy manufactured and sold the ASR XL Acetabular System and ASR Hip Resurfacing System in 2003. After FDA clearance was achieved via the 510(k)-approval process, ASR implants were launched in the United States in 2008. The premarket notification, popularly known as the 510(k)-approval process, preapproves products that are deemed “su

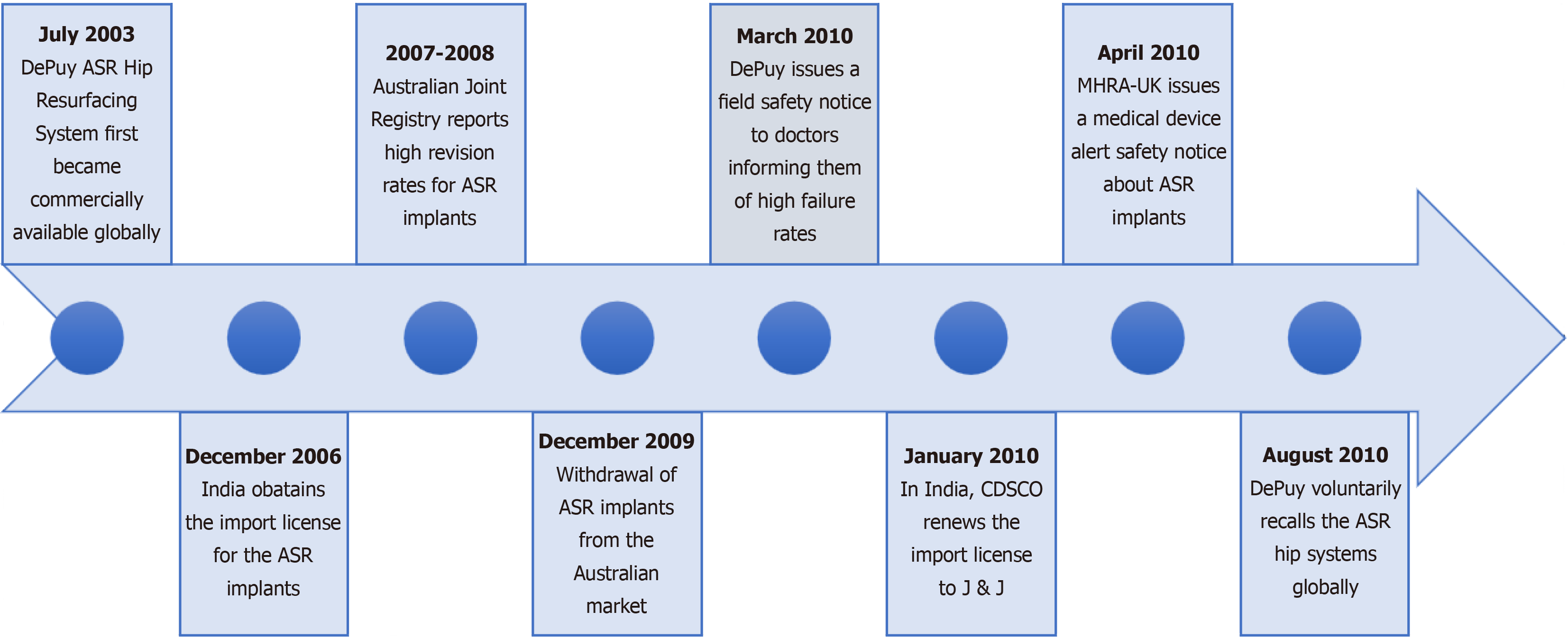

DePuy-engineered ASR hip implants have been used in more than 93,000 hip replacement surgeries worldwide[5]. However, concerns have emerged regarding complaints pertaining to complications associated with the implants. When the artificial ball and socket components interact, friction occurs, which causes wear. In cases where the implant is metal-on-metal, this friction can release metallic particles into the bloodstream, resulting in significant complications that may necessitate revision surgery. Experts have reported that elevated levels of cobalt and chromium in the blood can lead to toxicity and that metal ions are known to harm tissues and organs. In 2007, an analysis by the TGA in Australia revealed that the ASR Hip Resurfacing System had a higher-than-average replacement rate. In 2009, after reporting a high rate of failure, Australia subsequently took the regulatory initiative to withdraw the product from its market[6], setting a precedent for other countries to follow suit. Consequently, DePuy issued a global recall in August 2010. Interestingly, on December 23, 2009, the firm obtained a new registration certificate for ASR implants in India. Thereafter, on January 11, 2010, the firm renewed its import license on the basis of this registration, just a few months before the global product recall[7]. The timeline of the J&J faulty hip implant case, as shown in Figure 1, covers events from the initial release in 2003 to the global recall in 2010.

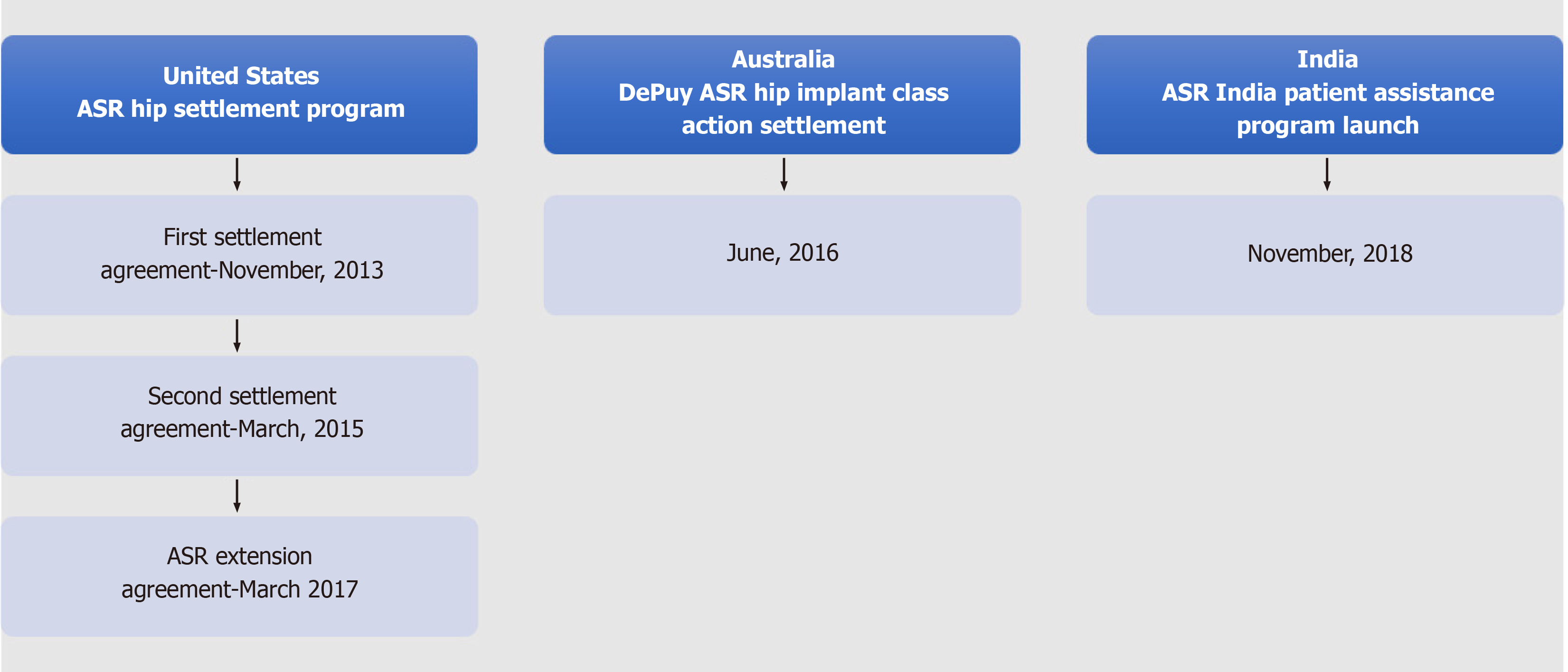

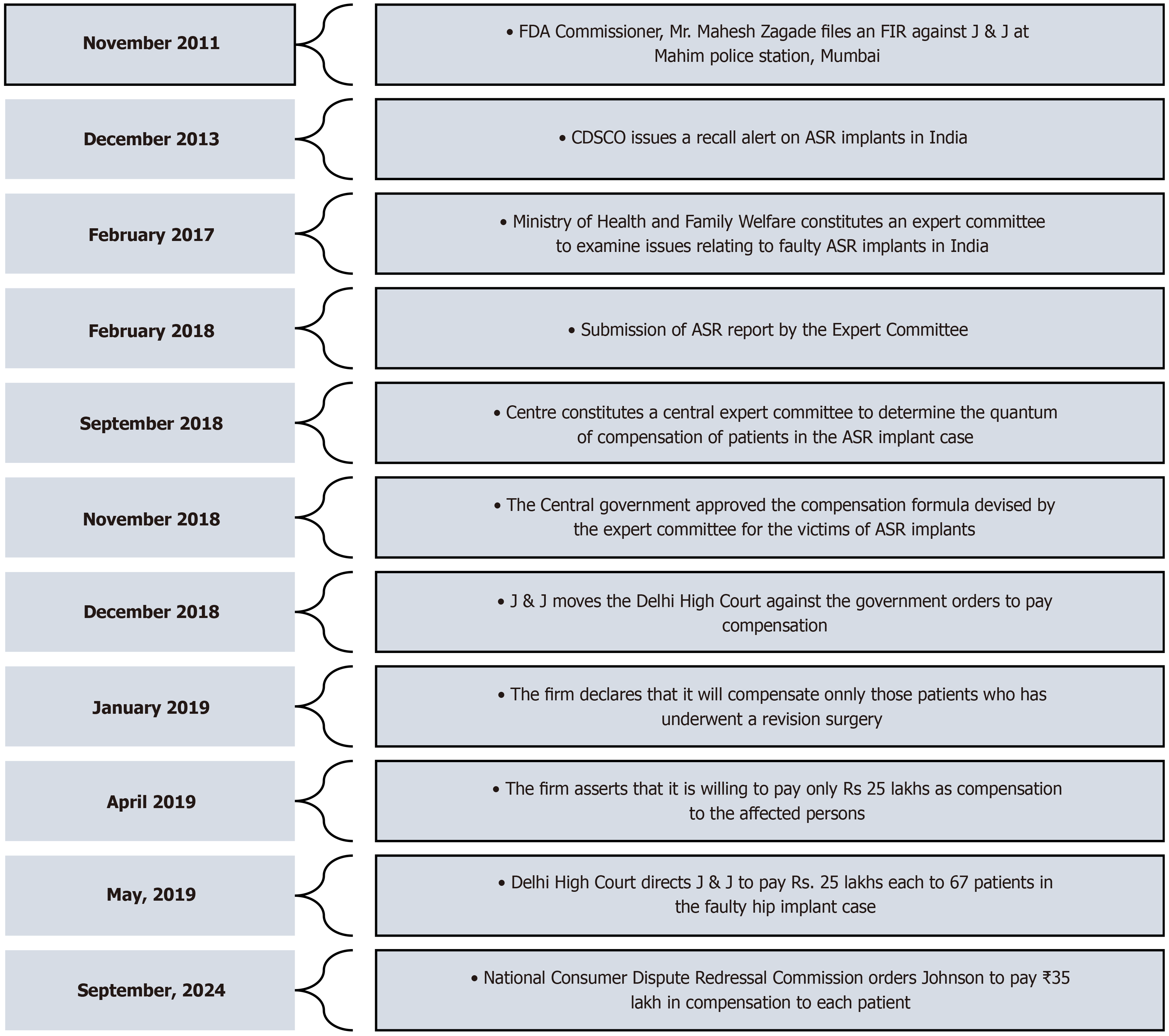

After receiving an anonymous complaint about a patient experiencing severe adverse reactions due to the use of ASR hip plants, the Maharashtra FDA filed an FIR against J&J in 2011. Subsequently, the matter was brought to the attention of CDSCO to raise awareness about faulty hip implants and to revoke J&J’s import license. On April 11, 2012, nearly three years after the global recall of the product, the CDSCO cancelled the product’s import license. The action taken by the CDSCO was prompted by a complaint from the Joint Commissioner of the Food and Drugs Agency, indicating that the firm had not implemented remedial measures or informed patients about the serious defects and adverse effects of the implant. Finally, on December 13, 2013, the CDSCO issued a medical device recall notice for the J&J’s faulty hip implants in India. Nearly 4700 ASR surgeries were carried out in India, of which only approximately 23% could be traced. While no compensation was made by the firm in India, in the United States, the firm agreed to provide compensation of nearly $2.5 billion USD to 8000 claimants[8]. Similarly, in Australia, the class action was settled for $250 million USD. Figure 2 outlines the initiation and settlement timelines of the DePuy ASR implant case in the United States, India, and Australia.

While the company launched a global reimbursement program for revision surgeries in 2010, revision surgeries in India commenced only in 2013[9]. In 2014, the firm went on to state that only out-of-pocket expenses incurred by patients would be reimbursed. Later, in 2017, the Health Ministry established an expert committee led by Dr. Arun Kumar Agarwal, former Dean and Professor of ENT at Maulana Azad Medical College, to investigate the concerns arising from defective ASR implants in India. After the investigation, the committee submitted an extensive report suggesting that the ASR reimbursement program be extended until August 2025, that sincere efforts be made to trace all patients who have received ASR implants and that compensation be granted to all affected patients. The committee also added that the grant of reimbursement, as agreed upon by the firm, for revision surgeries cannot be equated with compensation, as the patients had to undergo revision surgery only owing to the faults associated with the device and the negligence of the firm. Some general recommendations were also put forth by the committee, which included the establishment of an independent registry for monitoring high-risk medical devices, strengthening the Materiovigilance Program of India to monitor adverse events and including provisions for compensation in the Medical Devices Rules 2017. Finally, to determine the amount of compensation, the committee recommended the constitution of central and regional expert committees[10].

As per the recommendations of the report accepted by the Central government, a Central Expert Committee headed by Dr. R.K. Arya was constituted to ascertain the amount of compensation. State-level committees were also formed so that patients could approach and submit detailed application forms along with documents supporting their claims. In ad

Meanwhile, Mr. Goenka, a Delhi resident, filed a PIL in the Supreme Court. Mr. Goenka’s mother was a victim of the faulty implant, and he had already filed a consumer complaint against the J&J subsidiary, which was pending before the National Commission. He noted that although the Agarwal committee was formed to investigate faulty implant cases, few initiatives were taken to identify the large number of patients who underwent surgery. Later, the PIL was disposed of in view of the government’s decision to award compensation to the victims as per the recommendations of the Central Expert Committee[12].

On the basis of the recommendations of the Central Expert Committee, CDSCO directed J&J to pay Rs. 74.5 lakh and Rs. 65 lakh, respectively, to two patients from Maharashtra and Rs. 1 crore and Rs. 90 lakh to two patients from Uttar Pradesh. However, the pharma giants moved the Delhi High Court against the government's orders and stated that they were willing to pay only Rs. 25 lakh each. They also noted that only 250 had registered and that they would compensate them after a verification process. Additionally, the company alleged that the Central Government did not have the power to form the committee or issue directions regarding payment of compensation as per the Drugs and Cosmetics Act. The Delhi High Court directed J&J to pay Rs. 25 lakh to each patient as interim compensation[13]. A final decision regarding whether the compensation needs to be limited to those who underwent revision surgery, as well as the amount of compensation, has not yet been made by the court. Moreover, in September 2024, the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission ordered J&J, along with DePuy Orthopedics Inc. and DePuy Medical, to compensate two elderly women in two distinct cases, with Rs. 35 lakh each, for the significant medical and financial difficulties they faced due to faulty hip implants. The key developments in the J&J faulty hip implant case from 2011 to 2024 are detailed in Figure 3, which provides a comprehensive timeline of events during this period.

The Expert Committee, chaired by Dr. Arun Kumar Agarwal, revealed findings in its report on ASR surgeries in India, pointing to significant gaps in patient follow-up and information dissemination. According to the data, out of approximately 15829 ASR implants imported into the country, only 882 patients, accounting for a total of 1056 surgeries, could be traced through the ASR helpline. The firm informed CDSCO that approximately 4700 procedures were performed, and 1295 unused products were returned to the company as of September 2010[10]. However, the firm did not provide specific patient details, as they contended that such information was confidential and could only be accessed by the treating surgeons and hospitals and that the same information could not be disclosed to a third party. Unfortunately, owing to these factors, nearly 3600 patients remain untraceable, leaving them unaware of the potential defects in their implants without the crucial information needed to seek recourse or proper medical care. Furthermore, it should be noted that despite the implants being recalled in August 2010, the import license for the product was not cancelled until April 2012. This delay allowed the product to remain obtainable in the country regardless of global recall. Furthermore, a public notice regarding the recall was issued by the firm through newspapers only in March 2015, indicating inadequate efforts to locate and notify the affected individuals.

Additionally, India lacks a national registry or comprehensive healthcare database that systematically maintains the details of patients who have received implanted medical devices approved by foreign regulatory bodies. In addition, India did not have an adequate mechanism for monitoring and reporting adverse events related to medical devices at that time. As a result, defective implants continue to be sold to thousands of patients in India, even after global product recall. National registries are essential for tracking all implantable medical devices and facilitating the study of adverse events associated with these devices, ultimately protecting patients and improving their outcomes. In countries such as the United Kingdom, a National Joint Registry provides open-access reports to the public and detailed confidential per

The expert committee established by the Union Health Ministry noted that the firm had withheld crucial information from CDSCO, which was a serious violation of the approval conditions. In March 2009, when the firm sought a re

The report confirmed that nearly 4700 ASR surgeries were performed in India between 2004 and 2010. However, the firm considered only those patients who underwent revision surgery to be eligible for compensation, reducing the number to 254. The committee concluded that metal-on-metal implants result in high levels of cobalt and chromium in the blood, which leads to toxicity and damage to tissues and body organs. The report also states that victims of faulty hip implants were compelled to live a compromised life, putting them in severe pain and agony. It is reasonable to assume that many patients do not opt for revision surgery because of the painful nature of the procedure and that some may have died from their suffering. An article titled “How safe are metal-on-metal hip implants?” published in the British Medical Journal cites a DePuy internal memo from July 2005, which discusses the carcinogenic effects of wear debris from joint replacements. The memo also draws attention to a study suggesting a threefold risk of lymphoma and leukemia ten years after joint replacement, raising concerns about the distant effects[15]. In these circumstances, it is rather unfair to make a classification wherein only patients who underwent revision surgery would be reimbursed. Moreover, every patient who received a faulty hip implant must have experienced some level of harm, regardless of whether it resulted in revision surgery. The report also highlighted that revision surgeries not only negatively affect patients' quality of life but also impose significant physical, mental, psychological, and financial burdens on their families. Therefore, the firm's decision to limit reimbursements to only those patients who underwent revision surgery was unjust and arbitrary.

In addition, revision surgeries were necessary only because of faulty implants and the failure of the firm to take prompt measures to locate the victims. Under these circumstances, manufacturers should bear full responsibility for defective implants and the consequent harm to patients. However, in the absence of specific provisions for compensation under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, the firm contested the actions of the government to establish an expert committee that studied the case and prescribed compensation. Furthermore, the issue of product liability, whereby manufacturers can be held liable for defects in their products, was not defined under the Consumer Protection Act of 1986, creating ambiguities regarding compensation for affected individuals. These issues have set a dangerous precedent for victim compensation in India. Holding manufacturers accountable is crucial for ensuring patient safety and maintaining trust in the healthcare system. Such incidents erode citizens’ trust in systems designed to protect them.

The specifically constituted R K Arya Committee devised a compensation formula for victims of faulty implants on the basis of their age, degree of disability and other factors, whereby they would receive compensation ranging from Rs. 30 lakh to Rs. 1.23 crore[16]. However, the firm challenged this in the Delhi High Court and voluntarily agreed to pay Rs. 25 lakh to patients who have undergone revision surgery. Initially, 289 victims were identified by the CDSCO, 93 of whom underwent revision surgery. After verification, the firm narrowed its list to 67 patients[17]. Furthermore, the findings of the committee revealed that patients not only required revision surgery after the initial procedure but also, in some cases, underwent more than one revision surgery, causing significant physical and mental trauma. In addition, there are reports of multiple instances where patients have suffered from excruciating pain and metallosis (a condition caused by high levels of cobalt and chromium in the body), resulting in reduced sperm motility and even abortion[18]. Some have reported that, despite revision surgery, they have not been able to lead a normal life, causing immense mental distress. While it is acknowledged that no money can truly compensate for their suffering, it is fair for victims to receive compensation according to the committee's formula. Despite clear evidence of implant defects, the firm clarified that their Rs. 25 lakh payments should not be construed as an admission of liability. Ironically, the firm has paid up to $2.5 million in compensation abroad, which contradicts its stance on challenging compensation payments in India.

Until 2017, there was no perceived need to regulate medical devices. It was only after the tragic incident of the J&J faulty hip implant case that India sensed an urgent need to frame rules for the regulation of medical devices. The Medical Device Rules (MDRs) 2017 were drafted, giving effect to Sections 12 and 33 of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940, which came into effect on January 1, 2018. Like countries such as the United States, E.U., Canada, Japan, Australia, and China, MDR 2017 provides a risk-based classification of medical devices. The devices classified as low risk were placed under Class A, those classified as low to moderate risk were placed under Class B, those classified as moderate to high risk were placed under Class C, and those classified as high risk were placed under Class D[19]. The MDR also outlines safety and performance principles for medical devices[20] in accordance with the MoHFW guidelines and compliance with product standards[21] as established by the Bureau of Indian Standards or as notified by the MoHFW periodically. Licensing authorities, namely, the Central Licensing Authority (CLA) and State Licensing Authorities (SLAs), have been established to ensure compliance with national standards and regulations. While the rules concerning the import of all classes of medical devices, manufacturing of class C and class D devices, clinical investigations and approvals are overseen by the CLA, the SLA is tasked with enforcing rules related to the manufacture and distribution of class A and class B devices as well as the sale, stocking, exhibiting, or offering for sale or distribution of medical devices of all classes[22].

MDR 2017 was amended in 2020 to extend its scope to all medical devices. Before the amendment, only notified medical devices were regulated. The MDR (Amendment) Rules 2020 introduced provisions that provided specific deadlines for registering medical devices and obtaining licenses. According to these rules, importers and manufacturers were required to register all unregulated medical devices with the Drug Controller General of India by October 1, 2021. By October 1, 2022, importers, distributors, manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers of Class A and B devices were required to obtain a mandatory license, followed by Class C and D devices by October 1, 2023. Furthermore, for the registration of newly notified medical devices, a certificate of compliance with ISO-13485, accredited by the National Accreditation Board for Certification Bodies or International Accreditation Forum, is mandatory[23]. ISO 13485 aims to establish a robust quality management system for medical devices, ensure compliance with regulatory standards, enhance product safety and effectiveness, and facilitate global market access through consistent quality assurance practices.

On July 6, 2015, the MoHFW, Government of India, launched the Materiovigilance Programme of India (MvPI) at the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission (IPC) in Ghaziabad to monitor the safety of medical devices nationwide. The MvPI systematically collects and analyzes data on medical device-related adverse events, informs regulatory decisions, pro

The term ‘product liability’, though a well-known concept, especially under the Law of Torts, was not explicitly de

This study highlights critical deficiencies in India’s regulatory framework for medical devices, thereby validating both hypotheses.

India currently lacks a distinct legislative framework for regulating medical devices. According to the Medical Devices (Amendment) Rules, 2020, which took effect on April 1, 2020, all medical devices are categorized as drugs under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940. Although there may be similarities in the regulation of drugs, cosmetics, and medical devices, these categories are fundamentally distinct. Drugs encompass medicines and chemical or biological substances utilized for diagnosing, treating, or preventing diseases in humans and animals, whereas medical devices include a wide range of instruments, apparatuses, implants, and similar methods designed for the diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, prevention, or alleviation of diseases. Given the distinct nature of the risks associated with each, regulatory pathways and testing standards must differ to adequately address the unique safety and efficacy requirements. Several countries, including Canada, Brazil, and Japan, have introduced reforms and drafted separate legislation specifically for medical devices, highlighting the need for similar action in India.

The Medical Devices Rules 2017 focus primarily on compensation for clinical investigations involving investigational medical devices, leaving patients who suffer from faulty devices without a clear mechanism to hold manufacturers or importers accountable. Additionally, manufacturers are required to submit a comprehensive dossier that includes vital product specifications, design and manufacturing processes, and a certificate of conformity with recognized standards, as well as provide clinical evidence, conduct risk analyses, and implement postmarketing surveillance. However, the absence of enforceable penalties for failing to meet these obligations creates a significant gap in regulatory oversight. Furthermore, while the MvPI, launched by the IPC, is responsible for monitoring adverse events related to medical devices, reporting such incidents is merely recommended rather than enforced by law. This lack of a mandatory reporting requirement means that authorities face no penalties for failing to document adverse events, creating an environment in which issues may go unreported. Consequently, this significantly delays timely actions and interventions, exacerbating the risks faced by patients who rely on these devices.

The Medical Devices Rules allow import license applications to be submitted to the CLA without requiring clinical investigations if a free sale certificate is issued by regulatory authorities from countries such as the United States, the EU, Australia, Japan, or Canada. While this provision can expedite access to innovative technologies, it poses significant risks, as exemplified by the J&J faulty hip implant case, which underscores the importance of additional national-level testing to identify potential flaws and to protect Indian patients. The lack of rigorous monitoring and accountability for manufacturers leads to gaps in safety oversight. Without stringent local clinical investigation requirements and effective po

India lacks a centralized system to maintain comprehensive records of patients who have received medical devices, which complicates the identification and notification of individuals in the event of device failure. This deficiency often ne

The J&J faulty hip implant case highlights significant vulnerabilities in India’s medical device regulatory system, revealing critical gaps that threaten patient safety and undermine public trust. The alarming delay between the global recall and the local response-over three years-reflects a troubling lack of urgency and accountability. Consequently, 76% of affected patients remain untraceable, and compensation efforts have fallen significantly short, offering minimal re

Creating an independent agency dedicated to medical devices will foster specialized expertise, enable thorough evaluations, enhance compliance oversight, and effectively address unique challenges. This approach will fortify the regulatory framework, prioritizing patient safety and encouraging innovation.

Implementing compulsory clinical investigations for all medical devices—regardless of foreign approvals-will ensure that each product undergoes rigorous assessment aligned with India's specific safety and efficacy standards before entering the market. This strategy will bolster public health protection and strengthen confidence in medical technologies, ensuring that only safe and effective devices reach patients.

Developing a robust enhanced postmarket surveillance program that incorporates a legal mandate for adverse event reporting and real-time data collection to monitor device performance is essential. Involving healthcare professionals in this initiative will nurture a culture of safety and accountability, facilitating the swift identification and resolution of issues, and ultimately enhancing patient protection against faulty medical devices.

Establishing centralized registries to track individuals with implanted medical devices will allow for the rapid identification and notification of affected patients during device failure. This proactive strategy will significantly reduce the risks associated with complications, ensuring timely interventions and support for those affected. By implementing a systematic method for monitoring patient data, regulatory bodies can improve overall safety and responsiveness.

Building partnerships with established authorities such as the United States FDA, the European Medicines Agency, the TGA of Australia, and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency of Japan will enhance India's regulatory fra

Involving healthcare providers, patients, and industry representatives in the regulatory process is crucial for promoting transparency and trust. Conducting public consultations will help identify critical concerns and gather diverse per

Investing in comprehensive training programs for regulators and healthcare professionals is essential for enhancing oversight capabilities. These programs should emphasize advancements in medical technology and regulatory practices, including mechanisms for reporting adverse events. By equipping regulatory personnel to address emerging challenges, this initiative will promote patient safety and restore confidence in the healthcare system.

Developing well-defined legal frameworks to compensate patients harmed by faulty medical devices is essential. These frameworks create transparent pathways for victims to seek restitution, ensuring that they receive appropriate support. Clarity in these processes is vital for building public confidence in the regulatory system and demonstrating commitment to accountability.

Allocating government resources for independent research on the long-term safety and efficacy of medical devices is crucial. This funding will support rigorous studies to inform regulatory decisions and identify potential risks. By prioritizing research, India can strengthen its regulatory framework and increase public confidence in the oversight process, ultimately ensuring patient access to safe medical technologies.

Timely and systematic disclosure of information regarding device approvals, adverse event reports, and postmarket studies is essential to foster public trust and accountability. Prioritizing transparency empowers stakeholders to make informed decisions and enhance safety and responsibility within the medical device industry. This approach will bolster public confidence and improve the overall integrity of healthcare systems.

The implementation of these comprehensive reforms is not merely a necessity; it is also a moral imperative. By establishing a proactive and robust regulatory framework, India can safeguard patient health, restore public confidence, and avert future incidents that may be even more catastrophic than the J&J hip implant cases. The path forward must prioritize not only compliance but also the protection of citizens, ensuring that their health and well-being remain at the forefront of medical device regulation.

Furthermore, while countries such as the United States have enacted the Consolidated Appropriation Act (Omnibus) 2023 to bolster the cybersecurity of modern IoT-enabled medical devices, India’s reliance on legislation that dates back over 80 years introduces significant regulatory vulnerabilities, compromising patient safety and failing to address the demands of contemporary healthcare. Without proactive laws tailored specifically for medical devices, the risk of catastrophic incidents remains a pressing concern.

The J&J case reveals the dangers of insufficient regulation in India’s medical device sector. To prevent similar incidents in the future, the proposed reforms, as outlined above, are crucial for strengthening regulatory oversight, improving device management, and ensuring robust accountability mechanisms-ultimately safeguarding public health and enhancing the effectiveness of the system.

The author would like to express gratitude to Gujarat National Law University (GNLU) for providing access to essential resources that facilitated this research. Sincere thanks are extended to Mr. Vikas Gandhi, Professor at GNLU and colleagues for their invaluable insights and constructive feedback, which significantly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

| 1. | Howard JJ. Balancing innovation and medical device regulation: the case of modern metal-on-metal hip replacements. Med Devices (Auckl). 2016;9:267-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wienroth M, McCormack P, Joyce TJ. Precaution, governance and the failure of medical implants: the ASR((TM)) hip in the UK. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2014;10:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Parliament of Australia. Chapter 3- High revision rates: the consumer experience. Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/senate/community_affairs/completed_inquiries/2010-13/medicaldevices/report/c03. |

| 4. | Sharma VN. Playing with the lives in Johnson & Johnson way, Government authorities failed to provide safety to Indian Patients. 2018. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/lawtics/playing-with-the-lives-in-johnson-johnson-way-government-authorities-failed-to-provide-safety-to-indian-patients/. |

| 5. | Singer N. Johnson & Johnson Recalls Hip Implants. The New York Times. 2010. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/27/business/27hip.html. |

| 6. | Graves SE. What is happening with hip replacement? Med J Aust. 2011;194:620-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mahapatra D. UPA allowed import of faulty Johnson & Johnson implants. The Times of India. 2018. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/upa-allowed-import-of-faulty-johnson-johnson-implants-centre-in-sc/articleshow/67084384.cms. |

| 8. | Meier B. Johnson & Johnson in Deal to Settle Hip Implant Lawsuits. The New York Times. 2013. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/20/business/johnson-johnson-to-offer-2-5-billion-hip-device-settlement.html. |

| 9. | Kaunain Sheriff M. Johnson & Johnson admitted: Many young patients were affected by faulty hip implants, The Indian Express. 2018. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/johnson-johnson-admitted-many-young-patients-were-affected-by-faulty-hip-implants-5331864/. |

| 10. | Report of the Expert Committee to address the issue of faulty ASR hip implants, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2018. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/opencms/system/modules/CDSCO.WEB/elements/common_download.jsp?num_id_pk=ODQ0. |

| 11. | Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Health Ministry approves compensation formula for Hip implant cases. 2018. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1554266. |

| 12. | Arun Kumar Goenka vs. Union of India & Ors., WP(C) 1085/2018 in the Hon'ble Supreme Court of India, Judgement dated January 11, 2019. Available from: https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2018/29965/29965_2018_Order_11-Jan-2019.pdf. |

| 13. | Pramod Kumar Gupta vs Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, CIC/MH&FW/A/2018/131153-BJ. 2019. Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/135245770/. |

| 14. | Vaidya SV, Jogani AD, Pachore JA, Armstrong R, Vaidya CS. India Joining the World of Hip and Knee Registries: Present Status-A Leap Forward. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55:46-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cohen D. How safe are metal-on-metal hip implants? BMJ. 2012;344:e1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ghosh A. Faulty hip implants: Health ministry approves formula for compensation. The Indian Express. 2018. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/faulty-hip-implants-johnson-and-johnson-health-ministry-approves-formula-for-compensation-5471645/. |

| 17. | Singh SR, Perappadan BS. J&J offers ₹25 lakh to all patients for faulty implant. The Hindu. 2019. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/jj-offers-25-lakh-to-all-patients-for-faulty-implant/article27357547.ece. |

| 18. | Kaunain Sheriff M. How Johnson and Johnson hip implants system went wrong. The Indian Express. 2018. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/johnson-and-johnson-how-hip-implants-went-wrong-jp-nada-5331779/. |

| 19. | Rule 4, Medical Devices Rules, 2017 Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2022/m_device/Medical%20Devices%20Rules,%202017.pdf. |

| 20. | Rule 6, Medical Devices Rules, 2017. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2022/m_device/Medical%20Devices%20Rules,%202017.pdf. |

| 21. | Rule 7, Medical Devices Rules, 2017. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2022/m_device/Medical%20Devices%20Rules,%202017.pdf. |

| 22. | Rule 8 (1) & (2), Medical Devices Rules, 2017. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2022/m_device/Medical%20Devices%20Rules,%202017.pdf. |

| 23. | Rule 19B (2) (iii), the Medical Devices (Amendment) Rules, 2020. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/opencms/system/modules/CDSCO.WEB/elements/download_file_division.jsp?num_id=NTU0OQ==. |

| 24. | Seventh Schedule, Medical Devices Rules. 2017. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2022/m_device/Medical%20Devices%20Rules,%202017.pdf. |

| 25. | Sec. 2 (34), Consumer Protection Act, 2019. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15256/1/a2019-35.pdf. |

| 26. | Sec. 84 (1), Consumer Protection Act, 2019 available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15256/1/a2019-35.pdf. |

| 27. | Sec. 2 (35), Consumer Protection Act, 2019. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15256/1/a2019-35.pdf. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/