©The Author(s) 2025.

World J Orthop. Dec 18, 2025; 16(12): 110510

Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110510

Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110510

Figure 1 Illustration of the biomechanical principle of halo gravity traction.

A: Depicting a schematic of the sagittal view of a patient on halo traction, where a vertically oriented traction force is applied to the skull and connected to an overhead pulley system. External weight applied through the pulley pulls the spine against gravity; B: Depicting a schematic of the frontal view of a patient demonstrating that the traction is in line with the center of the head and spine.

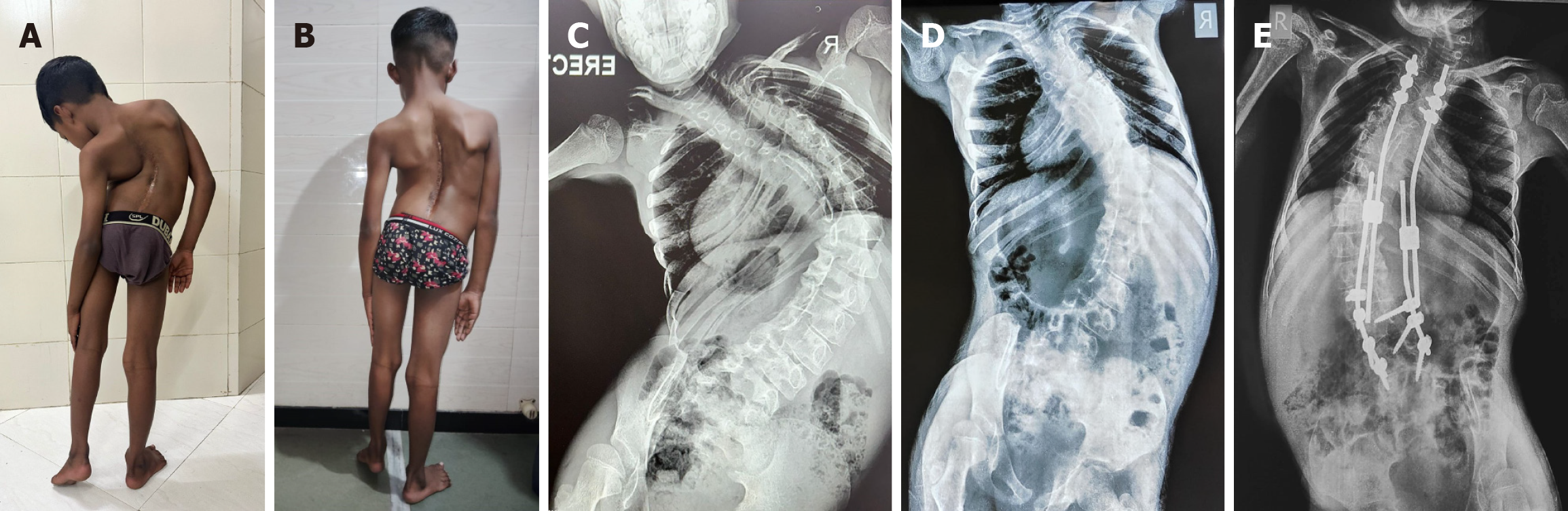

Figure 2 An illustrative example of severe scoliosis corrected with a staged procedure-halo gravity traction followed by posterior instrumentation and fusion.

A: Clinical picture of a 9-year-old boy, previously operated for diastematomyelia with severe thoracolumbar scoliosis with a decompensated curve; B: Clinical picture after application of halo gravity traction for 6 weeks and application of growing rods; C: Preoperative radiograph demonstrating scoliotic curve with a Cobb angle of 114°; D: Radiograph immediately before spinal instrumentation showing a Cobb angle of 76° (38° correction after halo gravity traction for 6 weeks); E: Postoperative radiograph with Cobb angle of 66 degrees after growing rod application.

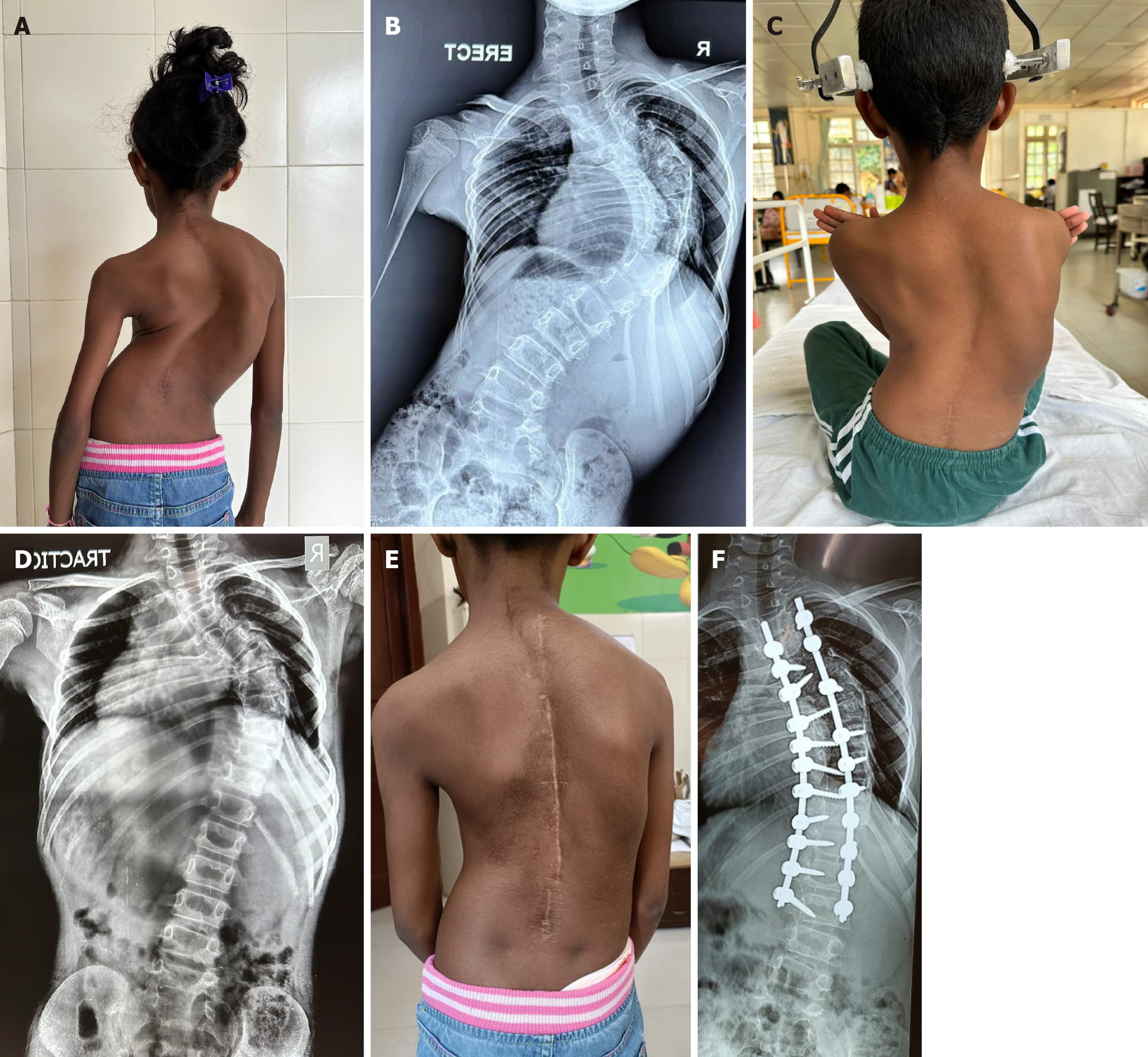

Figure 3 An eleven-year-old girl, previously operated case of spinal cord malformation type 2, was operated on for severe thoraco-lumbar scoliosis with halo gravity traction followed by posterior instrumented fusion.

No spinal osteotomies were done in this patient. A: Pre-operative clinical picture with a decompensated scoliosis; B: Preoperative radiographic image, with a Cobb angle of 96°; C: Patient with halo traction in the ward demonstrating improvement in the scoliosis; D: Radiograph taken immediately before posterior instrumented fusion, Cobb angle has improved to 61°; E: Post-operative clinical picture showing a balanced spine without spinal osteotomies; F: Radiographic image, one year after surgery, with Cobb angle of 31°.

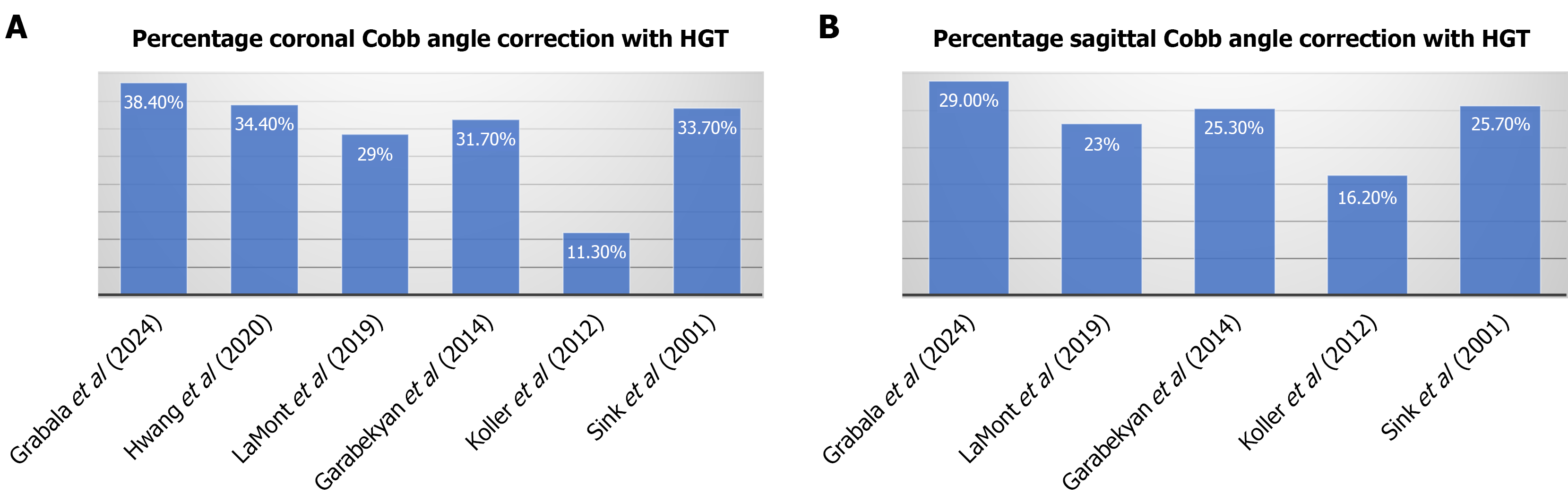

Figure 4 Coronal vs sagittal Cobb angle correction following halo gravity traction.

A: Graphs representing the percentage coronal Cobb angle correction after application of halo gravity traction as per various studies; B: Graphs representing percentage sagittal Cobb angle correction after application of halo gravity traction, as in various studies. HGT: Halo gravity traction.

Figure 5 Illustrative image describing pin positions during halo ring application.

A: Front view - shows safe zone, and pin position on the lateral half of the eyebrow; B: Side view - pin position one cm above eyebrow and medial to the temporalis muscle; C: Top view - shows pin position as seen from above.

Figure 6 Images demonstrate pin placement and halo frame setup.

A: Final assembly of the Halo frame, after insertion of all relevant pins; B and C: Final assembly for halo gravity traction in the ward.

Figure 7 Intra-operative position of an eleven-year-old girl with neurofibromatosis type I, before definitive posterior instrumented fusion.

The image depicts the placement of weight over the halo ring that helps in traction during surgery.

- Citation: Jain MA, Dhawale A, Iqbal MZ, Naseem A, Sagade B, Gorain A, Nene A. Halo gravity traction for pediatric scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis: A review of current evidence and best practices. World J Orthop 2025; 16(12): 110510

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i12/110510.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110510