Published online Sep 5, 2018. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v9.i4.31

Peer-review started: June 1, 2018

First decision: July 9, 2018

Revised: August 20, 2018

Accepted: August 26, 2018

Article in press: August 27, 2018

Published online: September 5, 2018

Processing time: 96 Days and 15.6 Hours

To describe the characteristics of adults who needed to see a doctor in the past year but could not due to the extra cost and assess the impact of limited financial resources on the receipt of routine fecal occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy for colon cancer screening among insured patients.

Data obtained from the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System included 215436 insured adults age 50-75 years. We computed frequencies, adjusted odds ratios (aORs), and 95%CIs using SAS v9.3 software.

Nine percent of the study population needed to see a doctor in the past year but could not because of cost. The numbers were significantly higher among those aged 50-64 (P < 0.0001), Non-Hispanic Whites (P < 0.0001), and those with a primary care physician (P < 0.0001) among other factors. Adjusting for possible confounders, aORs for not seeing the doctor in the past year because of cost were: stool occult blood test within last year aOR = 0.88; 95%CI: 0.76-1.02, sigmoidoscopy within last year aOR = 0.72; 95%CI: 0.48-1.07, colonoscopy within the last year aOR = 0.91; 95%CI: 0.81-1.02.

We found that the limited financial resources within the past 12 mo were significantly associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) non-screening. Patients with risk factors identified in this study should adhere to CRC guidelines and should receive financial help if needed.

Core tip: There is scarcity of data about role of “out-of-pocket costs” among insured patients. From a prospectively collected database of more than 200000 insured individuals, we found that almost 9% of the population could not see a doctor due to an out-of-pocket cost issue. This occurrence was significantly higher in African- Americans, and those without primary care physicians. Undergoing the stool occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy in past one-year was significantly associated with not following up with a physician because of cost. The results of our study show that limited financial resources are significantly associated with colorectal cancer non-screening in the insured Americans.

- Citation: Perisetti A, Khan H, George NE, Yendala R, Rafiq A, Blakely S, Rasmussen D, Villalpando N, Goyal H. Colorectal cancer screening use among insured adults: Is out-of-pocket cost a barrier to routine screening? World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2018; 9(4): 31-38

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v9/i4/31.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v9.i4.31

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States after breast and lung cancer[1]. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the five-year survival rate for CRC patients between the years 2007 and 2013 was only 64.9%[2]. As per the American Cancer Society (ACS, 2017), approximately 135430 patients would be diagnosed with CRC, representing 8% of all new cancer cases[3]. The mortality rates have been declining in the past decades which is thought to be mainly due to the widespread use of CRC screening[3]. The rate of decline in the CRC-related mortality has accelerated slightly; from 2005 to 2014, with rates decreased by an average of 2.5% per year[3]. However, this progress has lagged in the high-poverty and rural areas of the United States, including the lower Mississippi Delta and parts of Appalachia[2]. In the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable (NCCRT), almost 1500 organizations have committed to reducing CRC as a significant public health problem and are working toward an ambitious goal of reaching 80% screening rate for CRC by 2018[4].

The screening rate for CRC was 52.1% in 2008 and 62.6% in 2015[5]. Colonoscopy can reduce CRC mortality by almost 50%[6]. Screening rates are known to be higher among individuals with high income and higher education[7]. Unfortunately, for many individuals, CRC screening is not a priority due to multiple possible reasons. Over the past decade, intense research has been focused on predictors of CRC screening to improve the screening rates[8]. Availability of health insurance, the level of income, educational status, and access to a personal doctor, obesity, and race were significant predictors of CRC non-screening rates[9-11]. Though uninsured individuals are at high-risk for non-screening, studies related to the barriers to CRC screening among insured individuals are scarce[9].

The financial burden of CRC screening is huge in the United States[3]. In a comparative effectiveness study on CRC screening procedures, the yearly cost for providing fecal immunochemical tests (FITs) to 5863 patients was estimated to be $1.47 million whereas the annual cost for providing colonoscopies for 4869 patients was expected to be $5.17 million[12]. However, the adenoma detection rate with FIT’s was only 1.6% as compared to the colonoscopies, which detected 23.6% of adenoma[12]. Therefore, while costs vary considerably, the differences between the tests’ sensitivities are worth the extra cost. Beyond screening costs, medical costs of treatment were even more extreme in the United States In 2014, the direct medical costs of CRC added up to roughly $14 billion[3].

With the introduction of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), a larger percentage of adults obtained health insurance[13]. We studied the barriers to routine CRC screening in an “insured population” which might predict who will be screened in the future. Even though a larger percentage of adults are becoming “insured”, the “out-of-pocket” costs for CRC screening might also affect the screening rate[14]. There is a limited data on the barriers to screening in insured adults, but “out-of-pocket costs” appear to be emerging as an essential factor in the prediction of screening[15]. Despite having health insurance, the out-of-pocket cost might be an important variable for potential recipients of the screening and hence could be a target for future research. Several studies have studied the effects of out-of-pocket costs on uninsured individuals, but there is a huge gap in the research about these effects on insured individuals.

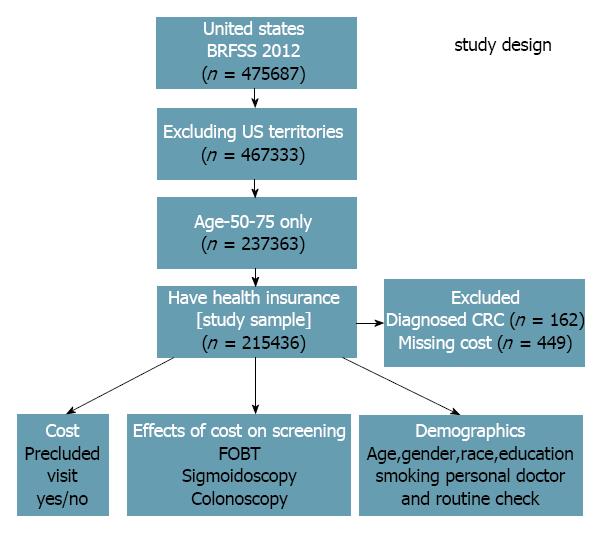

We utilized the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2012, a United States national database, to apply individual predictors affecting the CRC screening. BRFSS is a random-digit-dialed telephone survey of the noninstitutionalized United States civilian population aged 18 and older. Individuals were asked the demographic and health-related questions such as the insurance status, visits to doctors in specified time periods, screenings received, and influence of “out-of-pocket” visiting a physician and getting screened. Initially, 475687 individuals were surveyed in the BRFSS 2012 (Figure 1). Excluding United States territories (Guam, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Northern Mariana Islands, and United States Virgin Islands), 467333 individuals were evaluated. Of these individuals, 237363 were aged between 50 to 75 years, and 216047 had health insurance. Financial data was not available regarding 449 people, and 162 were already diagnosed with CRC. Excluding these, a study sample of 215436 was obtained.

Demographic characteristics of the population are described in Table 1. Among these individuals with cost constraints, subjects were divided into an age 50-64 year group (10%, early CRC screening) and age 60-75 year group (5%, late CRC screening). We applied United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and ACS recommendations to assess the CRC screening rates among individuals who could and could not see a doctor due to cost (out-of-pocket) constraints. We computed frequencies, adjusted odds ratios (aORs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using Surveyfreq and Surveylogistic. SAS v.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to analyze the data in a manner that accounts for the BRFSS’s complex sample survey design.

| Variables | Cost precluded a doctor visit1 | Cost did not affect a doctor visit | P-value | Odds ratio (99%CI) |

| Total (n = 215436) | 16517 (9) | 198919 (91) | ||

| Age group (n) | ||||

| 50-64 (127569) | 12149 (73.6) | 115420 (58.0) | < 0.0001 | |

| 65-75 (87867) | 4368 (26.4) | 83499 (42.0) | 2.01 (1.92, 2.11) | |

| Gender (n) | ||||

| Male (86028) | 5442 (32.9) | 80586 (40.5) | < 0.0001 | |

| Female (129408) | 11075 (67.1) | 118333 (59.5) | 0.72 (0.69-0.75) | |

| Race/ethnicity (n) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic (177916) | 11806 (71.5) | 166110 (83.5) | < 0.0001 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic (16861) | 2107 (12.8) | 14754 (7.4) | 0.50 (0.47-0.53) | |

| Hispanic (7847) | 1049 (6.4) | 6798 (3.4) | 0.46 (0.41-0.51) | |

| Others (10314) | 1321 (8.0) | 8993 (4.5) | 0.48 (0.43-0.54) | |

| Education attainment (n) | ||||

| Did not Graduate High School (15280) | 2367 (14.3) | 12,913 (6.5) | < 0.0001 | |

| Graduated High School (62826) | 5439 (32.9) | 57387 (28.8) | 0.75 (0.70-0.80) | |

| Attended College/Technical School (58305) | 4852 (29.4) | 53453 (26.9) | 0.78 (0.74-0.83) | |

| Graduated College/Technical School (78388) | 3795 (23.0) | 74593 (37.5) | 1.40 (1.32-1.48) | |

| Health status (n) | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good (169114) | 8841 (53.5) | 160273 (80.6) | < 0.0001 | |

| Fair/poor (45648) | 7594 (46.0) | 38054 (19.1) | 0.28 (0.26-0.29) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal (2666) | 280 (1.7) | 2386 (1.2) | 0.0205 | |

| Overweight (60265) | 4099 (24.8) | 56166 (28.2) | 0.97 (0.82-1.15) | |

| Obese (77582) | 5177 (31.3) | 72405 (36.4) | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) | |

| Current smokers (n) | ||||

| Yes (31599) | 4119 (24.9) | 27480 (13.8) | < 0.0001 | 2.09 (1.99-2.20) |

| No (179993) | 12034 (72.9) | 167959 (84.4) | ||

| Binge drinkers2 (n) | ||||

| Yes (18355) | 1349 (8.2) | 17006 (8.5) | 0.9101 | |

| No (189647) | 14486 (87.7) | 175161 (88.1) | 0.96 (0.89-2.20) | |

| Have a personal doctor or health care, provider | ||||

| Yes, at least one (200482) | 14657 (88.7) | 185825 (93.4) | < 0.0001 | |

| No (14554) | 1801 (10.9) | 12753 (6.4) | 0.56 (0.52-0.60) |

Out of 215436 adults aged between 50 and 75 years, 9% (16517) individuals could not see a doctor due to out-of-pocket cost constraints even when in need of screening (Table 1). The prevalence of adults who could not afford to visit a doctor in the last 12 mo because of “out-of-pocket cost” was significantly higher among 50-64 years old individuals than 65-75 year (P < 0.0001); men compared to females (P < 0.0001); Non-Hispanic Whites in comparison to Non-Hispanic Blacks (P < 0.0001); those who were college graduates compared to those who did not graduate from high school (P < 0.0001). The prevalence of “unable to see a doctor due to cost constraint” in the past 12 mo was unusually high among respondents who were: Healthy adults in comparison to the adults with fair or poor health (P < 0.0001), non-smokers versus current smokers (P < 0.0001), and the individuals with a doctor compared to those without a personal doctor (P < 0.0001).

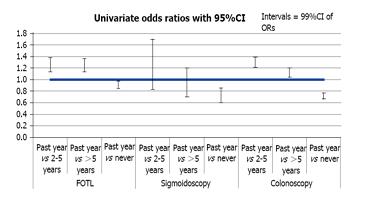

Among adults aged 50-75 years, 5913 individuals who never received a colonoscopy screening due to out-of-pocket cost constraints were lower than those without cost constraint (OR = 0.72). Similar observations were noted for the use of sigmoidoscopy and FOBT (Table 2). To assess the trend of CRC screening, we used the data from BRFSS 2008 and 2010 together with that for 2012. We compared adults with out-of-pocket cost constraint to adults who did not report a cost constraint, and found a significant association in receipt of a colonoscopy within the last 12 months for BRFSS 2008, 2010, and 2012 [aOR = 0.77; 95%CI: 0.69-0.85, 0.90 (0.82-0.99), 0.90 (0.80-1.00); respectively]. This was adjusted for age, gender, race, education level, general health status, having a personal doctor, the length of time since the last routine checkup, and per capita primary care physicians with a univariate logistic model (Figure 2). The odds of getting a colonoscopy screening in the past 12 months improved from 2008 to 2012 [aOR = 0.77; 95%CI: 0.69-0.85; 2008 vs 0.90 (0.80-1.00); 2012]. However, this was not seen with FOBT [aOR = 0.93; 95%CI: 0.83-1.05; 2008 vs 0.88 (0.77-1.01), 2012] or sigmoidoscopy [aOR = 0.72; 95%CI: 0.49-1.04; 2008 vs 0.69 (0.46-1.03), 2012], indicating there might be a paradigm shift towards colonoscopy as a preferred way of CRC screening compared to FOBT or sigmoidoscopy in recent years.

| Variables | Cost precluded a doctor visit | Cost did not preclude a doctor visit | P-value | Odds ratio (99%CI) |

| Time since last blood stool test (n) | ||||

| Within the past year (20496) | 1420 (9.1) | 19076 (10.0) | < 0.0001 | |

| Within the past 2 to < 5 yr (29863) | 1838 (11.8) | 28025 (14.9) | 1.25 (1.14-1.38) | |

| 5 or more years (25290) | 1569 (10.1) | 23721 (12.6) | 1.24 (1.13-1.36) | |

| Never (128556) | 10717 (68.9) | 117839 (62.5) | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) | |

| Time since last sigmoidoscopy (n) | ||||

| Within the past year (1053) | 80 (0.5) | 973 (0.5) | < 0.0001 | |

| Within the past 2 to < 5 yr (2645) | 172 (1.0) | 2473 (1.2) | 1.18 (0.82-1.70) | |

| 5 or more years (2888) | 238 (1.4) | 2650 (1.3) | 1.24 (1.13-1.36) | |

| Never (57443) | 5913 (35.8) | 51530 (25.9) | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) | |

| Time since last colonoscopy (n) | ||||

| Within the past year (33454) | 2316 (14.0) | 31138 (15.7) | < 0.0001 | |

| Within past 2 to < 5 yr (77619) | 4634 (28.1) | 72985 (36.7) | 1.29 (1.21-1.39) | |

| 5 or more years (28253) | 1931 (11.7) | 26322 (13.2) | 1.12 (1.04-1.20) | |

| Never (57443) | 5913 (35.8) | 51530 (25.9) | 0.72 (0.67-0.77) |

Our study indicates that out-of-pocket cost is a potential barrier in the colonoscopy for colon cancer screening among the insured population. Studies identifying barriers to CRC screening among insured adults are rare. Our study focuses on the “insured adults” compared to other studies that target the uninsured groups[16]. While the need to look at the uninsured population is essential, this study indicates that the same factors that limit screening colonoscopy in uninsured also affect many of the insured. With more adults obtaining health insurance due to the expanded ACA, concern about the out-of-pocket costs is increasing. Despite the expansion of health insurance, there are potential hidden costs that remain a barrier to the screening process[16-18]. Understanding the specifics of a health care plan might delineate some of the costs involved in the process.

The USPSTF recommends the use of either FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy as the approved CRC screening methods beginning at the age of 50 years in average-risk individuals[19]. Colonoscopy is the most preferred and accurate of all the screening methods but is also the most expensive[19-21]. FOBT can reduce the number of deaths from CRC by approximately 15% to 33%[21]. FOBT is a non-invasive test and can be easily done at home[21]. For patients avoiding screening due to embarrassment, social stigma, or lack of financial resources, FOBT can be a great solution to raise screening rates. People aged 50 to 60 years who are screened with sigmoidoscopy have a 70% lower risk of death due to CRC compared to those not screened[22]. Sigmoidoscopy is only needed every 5-years, making it convenient for patients living in the rural areas with limited transportation and medical care[23]. Lastly, screening colonoscopies have been shown to reduce the risk of death by 60% to 70%[20]. Colonoscopies are needed every ten years as recommended by the USPSTF, which helps to counteract its high cost[23]. While endoscopy procedures are invasive, the time and money spent on fewer screenings overall can be a great motivator for rural patients to increase their screening rate for CRC[22]. In the recent years, the virtual colonoscopy has been developed, which is performed via CT scan but in much less invasive fashion[24]. With this test, there are fewer risks of complications as well[24]. However, due to the lack of evidence for assessing the effectiveness of virtual colonoscopy due to the limited number of studies, it has not been accepted as a mainstream screening method. Moreover, extracolonic incidental findings on virtual colonoscopy can lead to over diagnosis and over treatment[23]. Some insurance companies including Medicare still do not cover this procedure making it a high out-of-pocket cost screening method not only for those who are uninsured but also for insured individuals. As one could expect, out-of-pocket costs affect all everyone in the population, and thus, all sectors of the population need to be studied in regards to this particular barrier to investigating whether this barrier is a significant driver of low CRC screening rates.

The ACS reports that disparities in CRC survival time are predominantly due to socioeconomic variables such as race/ethnicity, insurance coverage, and income[3]. These disparities also drive the access to early screening procedures, which influence the patients’ prognosis ultimately[3]. For instance, Non-Hispanic Blacks and American Indians or Alaskan Natives are the most likely to be diagnosed with metastatic CRC[3]. Non-Hispanic Whites, as well as Asian and Pacific Islanders, are most likely to be diagnosed with the local CRC, which is much easier to treat and cure[3]. Also, 5-year survival rates also indicate disparities[3]. For instance, only 11% of Non-Hispanic Blacks versus 14% of Non-Hispanic Whites live for 5-years after diagnosis of metastatic CRC[3].

Most healthcare insurance carriers divide the costs between premium (monthly fee to the insurance carrier), deductible (initial payment by beneficiary before insurance payment), cost-sharing (percentage of cost shared by insurance carrier and beneficiary), co-payment (cost for routine services which is not paid by deductible) and out-of-pocket cost (which is the absolute payment for healthcare cost annually). ACA recommends zero cost-sharing and zero co-payment (which includes screening colonoscopy)[13]. However, the amount of deductible and out-of-pocket cost remains unclear. Although out-of-pocket costs and co-payments are useful in a more meaningful utilization of the health care system, their use in screening procedures is debatable[17].

Screening colonoscopy is traditionally covered by most of the insurance carriers. However, if during the screening procedure, a lesion is identified, removed, and biopsied, it is termed as “diagnostic or therapeutic” colonoscopy. In most events, there would be additional costs related to pathology, anesthesia and facility fees. This leads to an ill-defined area, where screening colonoscopies turn into a diagnostic and may result in high co-payment and out-of-pocket cost to the patient[17]. These costs are difficult to predict, given that different insurance carriers charge differently (including within or out of network groups) which leads to varying costs for colonoscopies in the United States[14]. Also, state-specific rules apply with regards to the extent of coverage for the screening procedures[18]. It was previously reported that health insurance plans with high deductibles have a lower percentage of screening colonoscopy[15]. These hidden costs make the receipt of colonoscopy a costly affair for the beneficiary and might prevent the widespread screening of CRC[14].

The lack of health insurance, educational level, smoking, alcohol intake, non-availability of a personal doctor, race, and employment status are among some of the important barriers to routine CRC screening[9-11,25]. These barriers could be divided into provider, practice, or patient based[1,16]. In recent years there has been an increased need for the system-based methods to promote screening explicitly targeting patient-related barriers[26]. Among the obstacles which could potentially be reversible, lack of insurance coverage remains an important one[11,13,16]. Among barriers to colonoscopy, lack of a personal doctor, ethnicity, low socioeconomic status, lack of education, rural location and non-availability of health care coverage constitutes a vulnerable section[8-10,22,27]. Over the last few years, there has been a push to find an answer on how to raise the low CRC screening rates. Use of health information technologies, computerized reminders, mailed letters, clinician feedback, narrative interventions, a culturally targeted navigation system, care plan, clear goal setting, performance-based financial incentive, and personal telephone outreach has been found to increase the adherence to CRC screening[26,28-33]. Patients undergoing screening for other cancers like prostate, breast, or cervical are usually more adherent to CRC screening which indicates overall health as a variable for screening. This might be utilized by the health care providers to discuss the CRC screening during patient visits for other cancer screening[34]. Also, an active discussion about health care reforms and coverage with the patient and physician could probably help. An interactive multimedia computer program (IMCP) to expand psychosocial factors for promoting CRC screening was tried, but with limited success[35].

One of the strengths of this study is the inclusion of a large random sample. Furthermore, information about confounding variables affecting the colorectal screening helped in effective comparison. Availability of BRFSS data over 2008, 2010 and 2012 helped in predicting a trend. Also, the unique aspect of our focus on the insured individuals’ sheds light on an aspect of out-of-pocket barriers to screening that has not been explored prior to this study.

There are some potential limitations to our study. BRFSS is based on non-institutionalized adults and not patient-based data. However, as screening involves adults without symptoms, this is being of low significance. There are some missing data in the BRFSS that could limit our study interpretation. Subjects with precluded visits were more likely to have missed FOBT (P < 0.0001) as well as sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy (P < 0.0001) than individuals without a precluded visit. This is expected, given that adults who cannot afford to get screening due to the cost are more likely not to report or do not recall any screening events. Our data predominately includes white non-Hispanics population that could limit the validity of results. Given the one-time telephonic survey and cross-sectional causality could not be determined. Adults without access to a landline or cell phone are excluded from this survey. It is limited to adults speaking English or Spanish language. It is also obvious that some respondents may not give the information in its entirety during the self-reporting telephonic conversation. The results are limited to the US healthcare system, therefore, might not apply to other countries because of variation in colon cancer screening guidelines.

Our findings that out-of-pocket cost may be a barrier to the receipt of colonoscopy might have a potential role in future, larger studies. As we see the trend of increased recognition of colonoscopy as a CRC screening option compared to FOBT or sigmoidoscopy, the rate of receipt of colonoscopies is expected to rise in the future. This would probably be a paradigm shift with colonoscopy taking over as a predominant screening for CRC screening. Given the reversible nature of insurance coverage issues, a payment program targeting the vulnerable population either federal or state-funded among the insured adults might reduce the bridge between the target and current screening rate. Formulating designs and protocols to isolate the vulnerable adults from the impact of high out-of-pocket costs for screening might decrease the CRC mortality. Use of health savings accounts and access to insurance plans, which cover a large portion of the out-of-pocket costs, educating individuals and discussing these models probably will move closer to the targeted screening rate.

Over the past decade, intense research has been focused on predictors of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening to improve the screening rates. Availability of health insurance, the level of income, educational status, and access to a personal doctor, obesity, and race were found to be significant predictors of CRC non-screening rates in the past. Though uninsured individuals are at high-risk for non-screening, studies related to the barriers to CRC screening among insured individuals are scarce.

There is only limited information if out-of-pocket cost restraints in the insured population affect the receipt of coloscopy for CRC screening.

The main objective was to investigate if out-of-pocket cost restraint plays a part in not getting the screening colonoscopy.

The study was performed from a prospectively collected telephone database named Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (2012) included 215,436 insured adults age 50-75 years. We computed frequencies, adjusted odds ratios (aORs), and 95%CIs using SAS v9.3 software.

Nine percent of the insured population needed to see a doctor in the past year but could not because of cost. The numbers were significantly higher among those aged 50-64 (P < 0.0001), Non-Hispanic Whites (P < 0.0001), and those with a primary care physician (P < 0.0001) among other factors. Adjusting for possible confounders, aORs for not seeing the doctor in the past year because of cost were: stool occult blood test within last year aOR = 0.88; 95%CI: 0.76-1.02, sigmoidoscopy within last year aOR = 0.72; 95%CI: 0.48-1.07, colonoscopy within the last year aOR = 0.91; 95%CI: 0.81-1.02.

Out-of-pocket cost is a barrier to the receipt of colonoscopy in the insured population.

Further steps should be taken to target the insured population to increase the colon cancer screening.

We are grateful to Abe Sahmoun PhD (Director of research affairs, University of North Dakota School of Medicine) for his help with the statistical analysis and methodology. The authors also thank Dr. Edwin Grimsley, MD, MACP, for help in the development of audio core tip about the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Abdel-Salam OME, De Lusong MAA, Dumitrascu DL, Lee SH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25600] [Article Influence: 1706.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 2. | National Cancer Institute. Screening rates for several cancers miss their targets.2015. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2015/screening-targets. |

| 3. | American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts figures 2017-2019.2017. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2019.pdf. |

| 4. | National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. 80% by 2018.2018. Available from: http://nccrt.org/what-we-do/80-percent-by-2018/. |

| 5. | Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, Ganiats T, Levin T, Woolf S, Johnson D. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1501] [Cited by in RCA: 1436] [Article Influence: 62.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1952] [Cited by in RCA: 2379] [Article Influence: 169.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer vital statistics.2011. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/cancerscreening/colorectalcancer/index.html. |

| 8. | Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, Thompson T, Shapiro JA, Vernon SW, Coates RJ. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult U.S. population. Cancer. 2004;100:2093-2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cokkinides VE, Chao A, Smith RA, Vernon SW, Thun MJ. Correlates of underutilization of colorectal cancer screening among U.S. adults, age 50 years and older. Prev Med. 2003;36:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | James TM, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, Feng C, Ahluwalia JS. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening: a guideline-based analysis of adherence. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:228-233. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU. Health insurance and mortality in US adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2289-2295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wong MC, Ching JY, Chan VC, Sung JJ. The comparative cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening using faecal immunochemical test vs. colonoscopy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sommers BD, Wilson L. Fifty-four million additional Americans are receiving preventive services without cost-sharing under the Affordable Care Act. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation 2012; Issue brief Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/fifty-four-million-additional-americans-are-receiving-preventive-services-without-cost-sharing-under-affordable-care-act. |

| 14. | Ladabaum U, Levin Z, Mannalithara A, Brill JV, Bundorf MK. Colorectal testing utilization and payments in a large cohort of commercially insured US adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1513-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wharam JF, Graves AJ, Landon BE, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Two-year trends in colorectal cancer screening after switch to a high-deductible health plan. Med Care. 2011;49:865-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, Allen H, Baicker K; Oregon Health Study Group. THE OREGON HEALTH INSURANCE EXPERIMENT: EVIDENCE FROM THE FIRST YEAR. Q J Econ. 2012;127:1057-1106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 901] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Selby JV, Fireman BH, Swain BE. Effect of a copayment on use of the emergency department in a health maintenance organization. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:635-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jost TS. Health insurance exchanges: legal issues. J Law Med Ethics. 2009;37 Suppl 2:51-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1005] [Cited by in RCA: 1081] [Article Influence: 60.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 968] [Cited by in RCA: 1185] [Article Influence: 91.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Birkner B, Stock C. Diagnostic performance of guaiac-based fecal occult blood test in routine screening: state-wide analysis from Bavaria, Germany. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:427-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Coughlin SS, Thompson TD. Colorectal cancer screening practices among men and women in rural and nonrural areas of the United States, 1999. J Rural Health. 2004;20:118-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | U.S. Preventive Service Task Force. Final recommendations statement - Colorectal cancer: Screening2016. Available from: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening2#consider. |

| 24. | Rawl SM, Skinner CS, Perkins SM, Springston J, Wang HL, Russell KM, Tong Y, Gebregziabher N, Krier C, Smith-Howell E. Computer-delivered tailored intervention improves colon cancer screening knowledge and health beliefs of African-Americans. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:868-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Peterson NB, Dwyer KA, Mulvaney SA, Dietrich MS, Rothman RL. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1105-1112. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, Weil J, Balsley K, Ranalli L, Lee JY, Cameron KA, Ferreira MR, Stephens Q. Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1235-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wheeler SB, Kuo TM, Goyal RK, Meyer AM, Hassmiller Lich K, Gillen EM, Tyree S, Lewis CL, Crutchfield TM, Martens CE. Regional variation in colorectal cancer testing and geographic availability of care in a publicly insured population. Health Place. 2014;29:114-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Robinson CM, Cassells A, Greene MA, Dunn VH, Falkenstern KM, De Leon R, Beach ML. Telephone outreach to increase colon cancer screening in medicaid managed care organizations: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dillard AJ, Fagerlin A, Dal Cin S, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Narratives that address affective forecasting errors reduce perceived barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dulko D, Pace CM, Dittus KL, Sprague BL, Pollack LA, Hawkins NA, Geller BM. Barriers and facilitators to implementing cancer survivorship care plans. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:575-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kinney AY, Boonyasiriwat W, Walters ST, Pappas LM, Stroup AM, Schwartz MD, Edwards SL, Rogers A, Kohlmann WK, Boucher KM. Telehealth personalized cancer risk communication to motivate colonoscopy in relatives of patients with colorectal cancer: the family CARE Randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:654-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Levin TR, Jamieson L, Burley DA, Reyes J, Oehrli M, Caldwell C. Organized colorectal cancer screening in integrated health care systems. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33:101-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Murphy CC, Vernon SW, Haddock NM, Anderson ML, Chubak J, Green BB. Longitudinal predictors of colorectal cancer screening among participants in a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2014;66:123-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Carlos RC, Underwood W 3rd, Fendrick AM, Bernstein SJ. Behavioral associations between prostate and colon cancer screening. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:216-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jerant A, Kravitz RL, Sohler N, Fiscella K, Romero RL, Parnes B, Tancredi DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Slee C, Dvorak S. Sociopsychological tailoring to address colorectal cancer screening disparities: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:204-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |