Published online Nov 6, 2017. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i4.201

Peer-review started: May 3, 2017

First decision: June 15, 2017

Revised: June 15, 2017

Accepted: August 3, 2017

Article in press: August 4, 2017

Published online: November 6, 2017

Processing time: 126 Days and 0.4 Hours

To investigate the putative role of protozoan parasites in the development of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The study included 109 IBS consecutive adult patients fulfilling the Rome III criteria and 100 healthy control subjects. All study subjects filled a structured questionnaire, which covered demographic information and clinical data. Fresh stool samples were collected from patients and control subjects and processed within less than 2 h of collection. Iodine wet mounts and Trichrome stained smears prepared from fresh stool and sediment concentrate were microscopically examined for parasites. Blastocystis DNA was detected by polymerase chain reaction, and Cryptosporidium antigens were detected by ELISA.

A total of 109 IBS patients (31 males, 78 females) with a mean age ± SD of 27.25 ± 11.58 years (range: 16 -60 years) were enrolled in the study. The main IBS subtype based on the symptoms of these patients was constipation-predominant (88.7% of patients). A hundred healthy subjects (30 males, 70 females) with a mean ± SD age of 25.0 ± 9.13 years (range 18-66 years) were recruited as controls. In the IBS patients, Blastocystis DNA was detected in 25.7%, Cryptosporidium oocysts were observed in 9.2%, and Giardia cysts were observed in 11%. In the control subjects, Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium and Giardia were detected in 9%, 0%, and 1%, respectively. The difference in the presence of Blastocystis (P = 0.0034), Cryptosporidium (P = 0.0003), and Giardia (P = 0.0029) between IBS patients and controls was statistically significant by all methods used in this study.

Prevalence of Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium and Giardia is higher in IBS patients than in controls. These parasites are likely to have a role in the pathogenesis of IBS.

Core tip: A mounting body of evidence suggests that infections with protozoan parasites may be implicated in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). However, previous studies from different geographic regions have yielded conflicting results. The present study investigates the infection rate of protozoan parasites in Jordanian IBS patients. Our results indicate that infection with Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia spp. may play a role in the pathogenesis of IBS in a significant proportion of patients. Testing for these parasites in cases of presumed IBS may offer new insights into the pathogenesis of IBS and thus improve its management.

- Citation: Jadallah KA, Nimri LF, Ghanem RA. Protozoan parasites in irritable bowel syndrome: A case-control study. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2017; 8(4): 201-207

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v8/i4/201.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i4.201

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal disorder with a complex etiology and pathogenesis[1,2]. The cause of IBS is not well understood and a combination of genetic, physical, mental health problems and environmental factors have been proposed[3]. Triggers vary among patients, and they may include certain foods, hormones, medications, stress, or an acute episode of gastroenteritis[4,5].

Previous infections and persistent low-grade inflammation may play an important role in the pathogenesis of IBS[6]. Numerous IBS cases develop after acute enteric infection with different pathogens causing what is called post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), where symptoms develop and persist in patients who had not met the Rome criteria before[7,8]. The PI-IBS symptoms have been reported in a significant number of patients following infections with bacteria and viruses[9]. The duration of diarrhea during enteritis has been identified as the strongest risk factor for subsequent IBS development[10], which might reflect the severity of the initial inflammation.

Blastocystis hominis is one of the most common human intestinal protozoa in both developing and developed countries[11,12]. It is common in patients with diarrhea-predominant-IBS[1,13,14], and its possible role in the pathogenesis of IBS has been suggested. Infections with this parasite might be responsible for bowel dysfunction due to the penetration of mucosal layer[14].

Cryptosporidium parvum (C. parvum) accounts for about 20% of diarrheal episodes in children in developing countries and up to 9% of episodes in developed countries[15]. Infections are usually characterized by self-limiting diarrhea (1-2 wk) with severe abdominal pain. However, the duration of clinical symptoms is highly dependent on the person’s immunological status[16], and more severe and long lasting cases may develop in children, the elderly, and immunocopmrimsed individuals[12,17]. Cryptosporidium has been reported in IBS patients, with the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms after an acute episode of cryptosporidiosis despite recovery and parasite clearance[18,19]. Symptoms following C. parvum infection are similar to those described by IBS patients, suggesting that this parasite is a potential cause of PI-IBS.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the possible association of protozoan parasites with IBS. The detection of these pathogens in IBS cases may offer new insights into the pathogenesis and management of this complex disorder.

The study included 109 IBS consecutive adult patients fulfilling the Rome III criteria[5]. The patients were recruited at the gastroenterology outpatient clinics at King Abdullah University Hospital (KAUH) between September 2013 and April 2014.

The diagnosis of IBS was ascertained by an experienced gastroenterologist (KAJ). Patients who did not agree to sign an informed consent were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria were: Positive stool cultures for bacteria; steatorrhea; lactose intolerance; gluten sensitivity. Healthy subjects without current or previous gastrointestinal symptoms, attending the hospital during the same time period for routine examination or accompanying other patients were enrolled in the control group. All study participants gave written informed consent prior to study enrollment.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Abdullah University Hospital and by the Committee of Research on Human subjects at the Jordan University of Science and Technology.

Fresh stool samples were collected from patients and control subjects. All eligible subjects filled a structured questionnaire, which covered demographic information, and clinical data (e.g., IBS history; IBS subtype; previous bacterial, viral, and/or parasitic infection, postinfection treatment and any antibiotic therapy received in the three months prior to enrollement).

Stool samples were processed within less than 2 h of collection. Each sample was divided into two portions before processing. One portion was immediately processed for protozoan parasites and the second portion was kept refrigerated in Eppendorf tube preserved in absolute ethanol (ratio 3:1) for antigen and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing.

Collecting multiple stool samples per subject was not feasible. Therefore, as an alternative, a comprehensive examination of a single fresh stool sample from each subject was done using several laboratory techniques.

For each sample, normal saline wet mounts and Lugol’s iodine wet mounts were microscopically examined to initially observe parasites. To maximize recovery of different parasites stages, all stool samples were concentrated using the formalin-ether acetate sedimentation technique (FEA)[20], which is the Center for Disease Control (CDC) recommended stool concentration method for clinical laboratories. Iodine wet mounts; a trichrome stained smears and modified Kinyoun acid-fast stained smears were prepared from the concentrates. Slides were thoroughly screened (200 to 300 fields) for parasites by an experienced parasitologist using 40 × and 100 × oil immersion objectives, and results were recorded.

All stool samples were tested using an FDA-approved RIDASCREEN®Cryptosporidium ELISA kit (R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. This immunoassay is designed for the qualitative detection of C. parvum and C. hominis antigens in human stool samples.

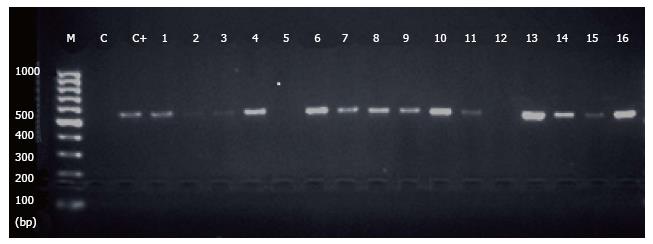

Genomic DNA was extracted from stool samples using QIAamp® Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration and purity were measured using NanoDrop microvolume UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, United States), and DNA was stored at -20 °C for later testing. The primers used were F1 (5′-GGAGGTAGT GACAATAAATC-3′) and BHCR seq3 (5′-TAAGACTACGAG GGT ATCTA-3′) (Integrated DNA Technology, Coralville, United States) targeting the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene of Blastocystis spp. [21]. Each PCR reaction contained 12.5 μL of GoTaq® Green Master Mix solution containing Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl2 and reaction buffers (Promega, United States), 0.5 μL of each primer, 5 μL of sample genomic DNA extract, and 5.5 μL of nuclease free water in a total volume of 25 μL. All PCR runs included a positive control containing the same components with a Blastocystis hominis suspension as DNA template (Microbiologics, United States), and a negative control containing the same components, but without DNA.

PCR amplification was performed using a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp 9600 thermal cycler. PCR amplification conditions were: Denaturation at 95 °C for 7 min, 35 cycles each consisting of denaturation 94 °C for 60 s, annealing at 56 °C for 45 s, followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products and 100 bp DNA ladder (Promega, United States) were loaded into 2% agarose gel, in TBE buffer, and bands were visualized under UV transluminator after staining with ethidium bromide. Positive samples for Blastocystis spp. had the DNA bands of 550-585 bp.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 19, Chicago, IL). Results are expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables (e.g., age), and proportions and percentages for categorical data (e.g., sex). Fisher’s exact test was used in the analysis of nominal variables to determine the significance of differences in parasite infection rates between the patients and the control subjects. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All P-values were two sided.

A total of 109 patients (31 males, 78 females) with a mean age ± SD of 27.25 ± 11.58 years (range: 16 -60 years) were enrolled in the study. A hundred healthy subjects (30 males, 70 females) with a mean ± SD age of 25.0 ± 9.13 years (range 18 - 66 years) were recruited as controls.The two groups were comparable in terms of age, sex and other demographic characteristics.

In the IBS cases, Blastocystis cyst-like form in moderate to many in numbers was observed in 16 (14.7%), Cryptosporidium oocysts were observed in 10 (9.2%) and Giardia lamblia cysts were observed in 9 (8.3%) (Table 1). Nonpathogenic Entamoeba hartmanni and Endolimax nana were each observed in 3 (2.8%) samples. Co-infections with 2 parasites were observed in 2 (1.8%) samples, one had Entamoeba hartmanni with Endolimax nana, and the second had Blastocystis spp. with Endolimax nana.

| Parasites observed | Un concentrates | P value | FEA concentrate | P value | ||

| IBS | Controls | IBS | Controls | |||

| Blastocystis spp. | 16 (14.7) | 3 (3.0) | 0.0034a | 12 (11.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0.0112a |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 10 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0017a | 10 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0017a |

| Giardia lamblia | 9 (8.3) | 1 (1.0) | 0.0197a | 12 (11.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0.0029a |

| Endolimax nana | 3 (2.8) | 1 (1.0) | 0.6228 | 3 (2.8) | 1 (1.0) | 0.6228 |

| Entamoeba hartmanni | 3 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2477 | 5 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2477 |

| Entamoeba histolytica/Entamoeba dipar | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Co-infections with 2 parasites | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.0) | 1 | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.0) | 1 |

In the 100 control samples, B. hominis was observed in 3 (3%) samples, Cryptosporidium in 0 (0%) samples, and Giardia lamblia cyst in 1 (1%) sample. Nonpathogenic Endolimax nana cyst was observed in 1 (1%) sample (Table 2).

| Test | Blastocystis spp. | Cryptosporidium spp. | ||||

| IBS | Controls | P value | IBS | Controls | P value | |

| Iodine wet mounts | 14 (12.8) | 3 (3.0) | 0.0106a | 10 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0017a |

| FEA | 12 (11.0) | 2 (2.0) | 0.0112a | 12 (11.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0003a |

| Trichrome stain | 14 (12.8) | 2 (2.0) | 0.0034a | 12 (11.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0003a |

| PCR | 28 (25.7) | 9 (9.0) | 0.0019a | - | - | - |

| Acid fast stain | - | - | - | 14 (12.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0001a |

| ELISA | ND | ND | - | 6 (5.5) | 1 (1.0) | 0.1211 |

In the iodine wet mount preparations of the sediment of IBS patients, Blastocystis was observed in 12 (11.0%) samples, Cryptosporidium was observed in 10 (9.2%) samples, and Giradia cysts in 12 (11.0%) samples. Other nonpathogenic amoebas were also observed (Table 1).

In the trichrome stained smears of the sediment of IBS patients, Blastocystis was observed in 14 (12.8%), Cryptosporidium oocysts appeared lightly stained or unstained in 12 (11.0%), and Giardia cysts were observed in 12 (11%) (Table 2).

In the control subjects, Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium and Giardia were observed in 2 (2%), 0 (0%), and 1 (1%), respectively. In the IBS patients acid fast stain of the sediment, Cryptosporidium was observed in 14 (12.8%) compared to none (0%) in the control samples.

In the IBS samples, 6 (5.5%) were positive for Cryptosporidium compared to only 1 (1.0%) positive in the controls (Table 2).

The specific DNA band was observed in 28 (25.7%) of the patients, compared to 9 (9%) of the controls (Figure 1). Comparing all methods used for the detection of Blastocystis (Table 2), PCR was more sensitive than the other techniques used. There was a significant difference between the cases and controls in all methods used: Iodine wet mount (P = 0.0106), FEA (P = 0.0112), the trichrome stain (P = 0034), and PCR (P = 0.0019).

Four of five tests used were consistent in the detection of the Cryptosporidium spp. and showed significant difference between the IBS patients and the controls (P values 0.0001 and 0.0017, respectively) (Table 2). Four IBS samples were positive for Blastocystis by all methods tested, and one sample was also positive for Cryptosporidium by ELISA.

The positive results of both parasites were associated with patients having more episodes of abdominal pain and discomfort or bloating than others. The main IBS subtype based on the symptoms of these patients was constipation-predominant IBS-C (88.7% of patients). Furthermore, stool samples were tested for bacterial pathogens (unpublished data), and patients having positive results were excluded from the study.

In this study, we investigated the prevalence of protozoan parasites in stool samples of IBS patients and healthy controls. Our results suggest that the occurrence of Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia spp. may have a role in the pathogenesis of IBS in a significant proportion of patients.

The presence of Blastocystis in 25.6% IBS patients was notably different (P = 0.0019) from the controls (9%), as detected by PCR (Table 2). These results are in agreement with previous studies, which reported higher infection rates of B. hominis in stool samples of IBS patients compared to controls[22,23]. Of note, PCR was reported to be superior over other techniques in the detection of Blastocystis in clinical samples[21].

Blastocystis has been reported as the most common intestinal parasite among both healthy and immunocompromised individuals[12], and highly prevalent in patients with acute and chronic diarrhea. In addition, a higher prevalence of Blastocystis spp. among IBS patients was reported as compared to patients suffering from other gastrointestinal disorders or healthy individuals[22,24]. In their epidemiological study, Giacometti et al[25] reported that Blastocystis was significantly present in IBS patients, suggesting a possible link between this parasite and IBS. Studies from the Middle East, Pakistan, Mexico and Europe[13,16,22,26,27] suggested a pathogenic role of Blastocystis in the etiology of IBS. However, other studies failed to demonstrate an association between Blastocystis and IBS[24,28]. A possible explanation for the differences in reporting could be the small number of IBS patients studied or the different diagnostic methods used. The multifactorial etiology of IBS, including microbiological factors, genetic, and environmental factors may also explain this discrepancy[23]. Blastocystis spp. ability to induce pathophysiological disturbances such as host cell apoptosis, the modulation of host immune response, toxic-allergic reactions leading to a nonspecific inflammation of the colonic mucosa has been linked to the pathogenesis of IBS[29,30]. It is well recognized that B. hominis is the single species infecting humans. However genetic analysis demonstrated antigenic heterogeneity, with nine different Blastocystis types that can infect humans, suggesting that virulent and avirulent species exist[24].

The detection of Cryptosporidium in 12.8% of IBS patients by the acid fast staining as compared to none detected in the control samples by any of the four methods used was statistically significant (Table 2). The relative prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. reported in several developed countries in outbreak and non outbreak settings ranges from 0.1% to 9.1% of clinical cases[11].

Similar to bacterial or other protozoan infections in humans, Cryptosporidium may trigger PI-IBS-like symptoms[19]. A study of immunocompetent rats infected with Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts suggested that cryptosporidiosis results in increased jejunal sensitivity to distension. This infection model mimicked some features of IBS patients, who report visceral pain as a major symptom and increased sensitivity to gut distension. The results of that study allow speculation that cryptosporidiosis may be a potential etiologic factor of IBS and warrant further studies of post cryptosporidiosis bowel disturbances[30]. In addition, an association between C. parvum with IBS was suggested in a study of immunocompetent suckling rat similar to PI-IBS features supported by the longterm pathological changes triggered by this parasite in the intestine[31]. Infections in these rats resulted in jejunal hypersensitivity to distension that was associated with accumulation of activated mast cells at 50 d post-infection[31]. These experimental results are consistent with the observation that diarrhea-predominant IBS patients have a marked increase in mast cell numbers and higher tryptase concentrations in jejunal mucosa[32].

Additionally, our results are in agreement with a previous study[33] that reported the permanent acid fast staining being more sensitive than iodine-stained wet mounts and ELISA for the detection of Cryptosporidium. In fact, acid fast staining is still considered the “gold standard” method routinely used for the detection of this parasite, although it may fail to detect infections in some symptomatic patients.

The presence of Giardia lamblia in IBS patients (8.3%) was also statistically significant in both concentrated and unconcentrated stool sediments (P = 0.0029 and 0.0197, respectively) (Table 2). The relative prevalence of Giardia intestinalis/lamblia in several developed countries in outbreak and other settings ranges from 0.2% to 29.2%[12]. Although most Giardia infections are self-limiting, chronic infections and re-infections can occur. A previous study reported Giardia in 5%-10% of IBS patients and provided evidence of potential cause of chronic PI-IBS symptoms[34]. High frequency of microscopic duodenal inflammation was found in post-giardiasis patients when the infection lasted 2-4 mo, indicating that longer duration of infection is a risk factor for PI-IBS[38]. However, the cause of the PI-IBS clinical manifestations due to Giardia, even after complete elimination of the parasite, remains unexplained.

Parasitic infections, and in particular Blastocystis hominis infection have been reported to be common in diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), suggesting a role for these parasites in the pathogenesis of IBS-D[1,13,14]. Of interest, Blastocystis hominis, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia spp were common also in our study patients, composed mainly of IBS-C subtype. Based on our results, we speculate that these parasites may play a role in the pathogenesis of IBS regardless of the subtype.

In conclusion, the significant presence of the protozoan parasites Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia spp in stool samples of IBS patients suggests a pathogenetic link between these parasites and IBS. Therefore, we recommend the inclusion of parasitological tests in the diagnostic work up for presumed IBS patients. Early diagnosis and treatment of these infections may shorten the duration of the infection and help reduce the risk of development of IBS. Further studies with a larger sample size and studies from epidemiologically different countries should provide more insight into the role of parasitic infections in the pathogenesis of IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder of uncertain etiology and multifaceted pathogenesis. Protozoa, such as Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia spp, are common enteric parasites and their carriage is believed to be linked to IBS.

There were several early published studies of the possible link between parasitic infections and the development of IBS symptoms. However, many of these studies have yielded inconsistent or even contradictory results.

The present study provides new pathophysiological insights into the role of protozoan parasites in IBS. Namely, Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia spp have been found to play a role in the pathogenesis of IBS in a significant proportion of patients.

Investigating the role of protozoan infections in the pathophysiology of IBS is important in clinical practice, especially in light of the opportunity of developing targeted therapies. Future research should focus on the subset of IBS patients with poor response to conventional therapy, and possibly offer newer, more effective treatment options.

Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by a complex pathogenesis, and various clinical manifestations. Protozoan parasites are a group of unicellular, eukaryotic microorganisms, which can infect both humans and animals; they include ciliates, amoebae, and flagellates.

The authors compared clinical data and test results of protozoan parasites for stool samples between in 109 patients with IBS and in 100 control individuals, demonstrated that prevalence of Blastocytosis, Cryptosporidium and Giardia is higher in OBS patients than in controls, and concluded that these parasites were likely to have a role in the pathogenesis of IBS. The paper is well-written and has interesting findings.

The Authors wish to thank the Deanship of Research, Jordan University of Science and Technology for funding the study. The Authors wish also to thank Dr. Yousef S Khader (Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Public Health, and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology) for his assistance in performing the biostatistical analysis.

| 1. | Boorom KF, Smith H, Nimri L, Viscogliosi E, Spanakos G, Parkar U, Li LH, Zhou XN, Ok UZ, Leelayoova S. Oh my aching gut: irritable bowel syndrome, Blastocystis, and asymptomatic infection. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712-721.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1456] [Article Influence: 104.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Borgaonkar MR, Ford DC, Marshall JK, Churchill E, Collins SM. The incidence of irritable bowel syndrome among community subjects with previous acute enteric infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1026-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shiotani A, Miyanishi T, Takahashi T. Sex differences in irritable bowel syndrome in Japanese university students. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:562-568. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3413] [Cited by in RCA: 3410] [Article Influence: 170.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | García Rodríguez LA, Ruigómez A, Panés J. Acute gastroenteritis is followed by an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1588-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Spiller R, Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1979-1988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Spiller RC. Distinctive clinical, psychological, and histological features of postinfective irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1578-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grover M. Role of gut pathogens in development of irritable bowel syndrome. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:11-18. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Neal KR, Hebden J, Spiller R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ. 1997;314:779-782. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fletcher SM, Stark D, Harkness J, Ellis J. Enteric protozoa in the developed world: a public health perspective. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:420-449. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Stark D, Barratt JL, van Hal S, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis JT. Clinical significance of enteric protozoa in the immunosuppressed human population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:634-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cekin AH, Cekin Y, Adakan Y, Tasdemir E, Koclar FG, Yolcular BO. Blastocystosis in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms: a case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stark D, van Hal S, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J. Irritable bowel syndrome: a review on the role of intestinal protozoa and the importance of their detection and diagnosis. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:80-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 709] [Cited by in RCA: 765] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leav BA, Mackay M, Ward HD. Cryptosporidium species: new insights and old challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:903-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Areeshi M, Dove W, Papaventsis D, Gatei W, Combe P, Grosjean P, Leatherbarrow H, Hart CA. Cryptosporidium species causing acute diarrhoea in children in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Engsbro AL, Stensvold CR, Vedel Nielsen H, Bytzer P. Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors of intestinal parasites in Danish primary care patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46:204-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hunter PR, Hughes S, Woodhouse S, Raj N, Syed Q, Chalmers RM, Verlander NQ, Goodacre J. Health sequelae of human cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:504-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Centers for Disase Control and Prevention. Laboratory identification of parasitic diseases of public health concern. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticProcedures/stool/specimenproc.html. |

| 21. | Roberts T, Barratt J, Harkness J, Ellis J, Stark D. Comparison of microscopy, culture, and conventional polymerase chain reaction for detection of blastocystis sp. in clinical stool samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:308-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jimenez-Gonzalez DE, Martinez-Flores WA, Reyes-Gordillo J, Ramirez-Miranda ME, Arroyo-Escalante S, Romero-Valdovinos M, Stark D, Souza-Saldivar V, Martinez-Hernandez F, Flisser A. Blastocystis infection is associated with irritable bowel syndrome in a Mexican patient population. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:1269-1275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Poirier P, Wawrzyniak I, Vivarès CP, Delbac F, El Alaoui H. New insights into Blastocystis spp.: a potential link with irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yakoob J, Jafri W, Beg MA, Abbas Z, Naz S, Islam M, Khan R. Blastocystis hominis and Dientamoeba fragilis in patients fulfilling irritable bowel syndrome criteria. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:679-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Fiorentini A, Fortuna M, Scalise G. Irritable bowel syndrome in patients with Blastocystis hominis infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:436-439. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Stensvold CR, Lewis HC, Hammerum AM, Porsbo LJ, Nielsen SS, Olsen KE, Arendrup MC, Nielsen HV, Mølbak K. Blastocystis: unravelling potential risk factors and clinical significance of a common but neglected parasite. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:1655-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Surangsrirat S, Thamrongwittawatpong L, Piyaniran W, Naaglor T, Khoprasert C, Taamasri P, Mungthin M, Leelayoova S. Assessment of the association between Blastocystis infection and irritable bowel syndrome. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93 Suppl 6:S119-S124. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Garavelli PL, Scaglione L, Bicocchi R, Libanore M. Pathogenicity of Blastocystis hominis. Infection. 1991;19:185. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Wawrzyniak I, Poirier P, Viscogliosi E, Dionigia M, Texier C, Delbac F, Alaoui HE. Blastocystis, an unrecognized parasite: an overview of pathogenesis and diagnosis. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2013;1:167-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Marion R, Baishanbo A, Gargala G, Francois A, Ducrotte P, Duclos C, Fioramonti J, Ballet JJ, Favennec L. Transient neonatal Cryptosporidium parvum infection triggers long-term jejunal hypersensitivity to distension in immunocompetent rats. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4387-4389. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Khaldi S, Gargala G, Le Goff L, Parey S, Francois A, Fioramonti J, Ballet JJ, Dupont JP, Ducrotté P, Favennec L. Cryptosporidium parvum isolate-dependent postinfectious jejunal hypersensitivity and mast cell accumulation in an immunocompetent rat model. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5163-5169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Guilarte M, Santos J, de Torres I, Alonso C, Vicario M, Ramos L, Martínez C, Casellas F, Saperas E, Malagelada JR. Diarrhoea-predominant IBS patients show mast cell activation and hyperplasia in the jejunum. Gut. 2007;56:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Mittal S, Sharma M, Chaudhary U, Yadav A. Comparison of ELISA and Microscopy for detection of Cryptosporidium in stool. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:DC07-DC08. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hanevik K, Dizdar V, Langeland N, Hausken T. Development of functional gastrointestinal disorders after Giardia lamblia infection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Jordan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Tosetti C, Watanabe T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ