Published online Feb 6, 2017. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i1.81

Peer-review started: July 12, 2016

First decision: September 12, 2016

Revised: September 27, 2016

Accepted: November 21, 2016

Article in press: November 22, 2016

Published online: February 6, 2017

Processing time: 198 Days and 12.8 Hours

To assess the development and implementation of the Integrated Rapid Assessment and Treatment (IRAT) pathway for the management of patients with fecal incontinence and measure its impact on patients’ care.

Patients referred to the colorectal unit in our hospital for the management of faecal incontinence were randomised to either the Standard Care pathway or the newly developed IRAT pathway in this feasibility study. The IRAT pathway is designed to provide a seamless multidisciplinary care to patients with faecal incontinence in a timely fashion. On the other hand, patients in the Standard Pathway were managed in the general colorectal clinic. Percentage improvements in St. Marks Incontinence Score, Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score and Rockwood Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale after completion of treatment in both groups were the primary outcome measures. Secondary endpoints were the time required to complete the management and patients’ satisfaction score. χ2, Mann-Whitney-U and Kendall tau-c correlation coefficient tests were used for comparison of outcomes of the two study groups. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Thirty-nine patients, 34 females, consented to participate. Thirty-one (79.5%) patients completed the final assessment and were included in the outcome analysis. There was no significant difference in the quality of life scales and incontinence scores. Patients in the IRAT pathway were more satisfied with the time required to complete management (P = 0.033) and had stronger agreement that all aspects of their problem were covered (P = 0.006).

Despite of the lack of significant difference in outcome measures, the new pathway has positively influenced patient’s mindset, which was reflected in a higher satisfaction score.

Core tip: Critical pathways and process mapping methodology was used in industry since the 1950s and in medical field since the 1980s. This randomised trial describes the implementation of the Integrated Rapid Assessment and Treatment pathway, that was designed to provide a seamless multidisciplinary care to patients with faecal incontinence in a timely fashion, and compares it to the current standard of care. Although, there was no significant difference in quality-of-life and incontinence scores after completion of management, the new pathway positively influenced patient’s mindset, as shown by the higher satisfaction scores. This is likely to reflect the structured support and thorough education patients in this group received.

- Citation: Hussain ZI, Lim M, Stojkovic S. Role of clinical pathway in improving the quality of care for patients with faecal incontinence: A randomised trial. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2017; 8(1): 81-89

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v8/i1/81.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i1.81

Critical pathways and process mapping methodology was used in industry, particularly in the field of engineering from as early as the 1950s. In the 1980s, clinicians in the United States began to develop the pathway tools and tried to re-define the delivery of care and attempted to identify measurable outcomes. Developed and used initially for the purpose of cost containment, in the United Kingdom in the late 1980s, the emphasis has been to use clinical pathways as a quality tool[1].

The initial focus was to reduce length of stay (LOS) with an emphasis on nursing care[2]. Originally, critical pathways began with admission and ended with discharge from the hospital. Today, they are usually interdisciplinary in focus, merging the medical and nursing plans of care with those of other disciplines, such as physical therapy, nutrition, or mental health. They provide opportunities for collaborative practice and team approaches that can maximize the expertise of multiple disciplines[1].

Goals of pathways include: (1) defining standards for expected LOS and for use of specific tests and treatments; (2) giving all team members a plan and specific roles; (3) decreasing nursing and physician documentation burdens; (4) providing a framework for collecting data; and (5) educating and involving patients and families in their care; and (6) provide better care through a mechanism that is able to coordinate clinical processes and to reduce unjustified variations and, ultimately, costs[2,3].

Clinical pathways have four main components[4], these are a timeline, categories of care or activities, intermediate and long term outcome criteria and variance record to allow deviations to be documented and analysed.

Here we describe the development and implementation of the Integrated Rapid Assessment and Treatment (IRAT) Pathway in the management of patients with faecal incontinence and report the outcome of a feasibility study.

A randomised controlled trial of patients in single centre.

Adult patients referred form primary care for management of faecal incontinence in York Teaching Hospital were prospectively recruited. Following patients’ initial referral, Invitation Letter and Patient Information Sheet were sent to all potential participants. Patients were then contacted by phone by the principal investigator to discuss any query they may have and obtain initial verbal consent prior to the written informed consent that was obtained on the first clinic visit.

Primary endpoints: Percentage improvement in Faecal Incontinence Scores and Rockwood Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scales Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale (FIQoLS).

Secondary endpoints: Time scale required to achieve full assessment and management of patients in each study group. Two periods of times were calculated; time from referral by primary care to first clinic appointment and time from initiation of management, i.e., first clinic appointment to competition of management; patient satisfaction.

Randomisation: Consenting patient who chose to participate in this study were randomised to either the IRAT pathway or the Standard Care pathway. Randomisation took place by mean of Sealed Envelope Randomisation Technique. Randomisation was performed by the Hull York Medical School Statistical Consultancy service in line with the York Hospital’s Standard Operating Procedure. Patients were informed about the results of randomisation by post together with the clinic appointment letter.

Sample size: This is a feasibility study. A sample size of forty patients was arbitrarily chosen conduct the study.

Ethical consideration: This study was approved by The North and East Yorkshire Alliance Research and Development Unit and the NRES Committee of the Yorkshire and the Humber Research Ethics Office. The REC reference number is 10/H1304/27.

The pelvic floor assessment pathway (PFAP) Form was developed, in cooperation with Clinical Effectiveness Team, in order to construct a data base for all participants in this study. It comprises two parts “one” and “two”, consisting of four (1.a, 1.b, 1.c and 1.d) and three (2.a, 2.b and 2.c) divisions respectively. Part 1 of the PFAP is concerned with documenting demographic data, medical and obstetric history, baseline St. Marks and Cleveland Faecal Incontinence Scores, baseline Rockwood FIQoLS, quality of life Visual Analogue Scale, in addition to questionnaires specific to assessment of faecal incontinence in line with NICE Guidelines recommendations. It also documents the results of anorectal laboratory studies (anorectal manometry, endoanal ultrasound, rectal compliance and anorectal mucosal electrosensitivity) in addition to any further investigation or assessment that might be required for managing individual patients. Part 2 of the PFAP documents patients’ management and monitors their progress and outcome. Patients’ outcome is assessed using similar assessment tools to those used in part 1, i.e., FIQoLS, St. marks incontinence score (SMIS) and cleveland clinic incontinence score (CCIS) in addition to patient satisfaction and feedback score. The later comprises 9 questions that cover patients’ perception of variance aspects of their management, including waiting time from referral to first clinic appointment, time required for completion of management, adequacy of time given to the patient, protection of patient’s privacy and the overall quality of care in addition to feedback about the PFAP form questionnaire itself. The patients were asked to rate these various aspects of care on a scale of 1 to 5, 1 being “strongly disagree” and 5 being “strongly agree”.

Developed in 1993, the CCIS[5] is probably still the most widely used FI severity scoring system. It gives a total score for the severity of the incontinence ranging between 0-20; where 0 represent full continence while 20 represent the worst possible incontinence. The CCIS comprises five questions accounting for incontinence to solid stool, liquid stool and flatus in addition to the use of protective pads and change in lifestyle. Each question is scored according to the frequency of occurrence of the symptom from 0 (never) - 4 (daily). This scoring system is simple and easy to understand and formed the base of almost all subsequent FI scoring systems that are currently used.

In addition to the five questions composing CCIS, St Mark’s Score[6] introduced an assessment of the ability to defer defecation, an additional score for the use of antidiarrhoeal medication and reduced the emphasis on the need to wear a pad. This scoring system comprises seven questions, each question is scored according to the frequency of occurrence of the symptom from 0 (never) - 4 (daily). The total score ranges between 0-24, where 0 indicates full continence while 24 represents the worst possible incontinence.

Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale[7] measures specific quality of life issues expected to affect patients with faecal incontinence. It is derived from a 29 item questionnaire comprising four domains; lifestyle, coping/behaviour, depression/self-perception and embarrassment. Each domain ranges from 1 to 4; with 1 indicating a lower functional status of quality of life.

IRAT Pathway is designed to provide a seamless multidisciplinary care to patients with faecal incontinence in a timely fashion. Patients referred from primary care are assessed and managed by a team of surgeons, pelvic floor physiotherapist, anorectal physiology nurse practitioner and an independent researcher. Each step in patient assessment and management “event” takes place according to a preconceived timetable.

To achieve the goals of the IRAT pathway, a specialised IRAT clinic was introduced where patients are seen and assessed jointly by a colorectal surgeon with special interest in the management of faecal incontinence, pelvic floor physiotherapist and a colorectal research fellow to assess and document patient progress. This clinic takes place once every 8 wk.

Events in the IRAT pathway: Participant randomised to IRAT pathway are asked to complete part 1.a. of the PFAP before attending the first IRAT clinic; week 1: Patients are seen in IRAT clinic by surgeons and physiotherapist, completing part 1.b of PFAP; week 3: Patients undergo assessment in the Anorectal Physiology Laboratory, Part 1.c of PFAP is completed by the patients and Part 1.d. of PFAP is completed by the nurse practitioner; between week 4-week 7: All patients undergo assessment by the pelvic floor physiotherapist for suitability of biofeedback; week 8: A second IRAT clinic visit takes place for reassessment and management plan based on anorectal physiology studies and clinical and biofeedback assessments, using part 2.a of PFAP; week 16: Follow-up after completion of management.

Events in the standard care pathway: Participant randomised to Standard Care Pathway are asked to complete part 1.a. of the PFAP before attending the first clinic; patients are seen in a colorectal clinic by colorectal surgeon, completing part 1.b of PFAP; patients are assessed and treated according to the surgeon’s clinical judgment. All management options available to patients in the IRAT pathway are also available to the Standard Clinic Pathway patients, including biofeedback, surgical intervention, etc. After completion of management, all patients, in both study arms, were asked to complete part 2.b. (final assessment) and 2.c. (patient satisfaction and feedback) of the PFAP for comparison of outcome. A reminder, by post, was sent to those who did not return the completed part 2.b. and 2.c. forms in a median of 2 mo.

Anorectal physiology laboratory assessment: Anal manometry study variables were obtained using an eight-channeled solid-state transducer catheter (Flexilog 3000, Oakfield Instruments Ltd, Evensham, Oxon, United Kingdom) using a continuous “pull through” technique. Manometric data were analysed using commercial software (Flexisoft III, Oakfield Instruments Ltd, Evensham, Oxon, United Kingdom). This included calculation of the maximum mean resting pressure, maximum mean squeeze pressure, resting (rVV), and squeeze (sVV), vector volumes, asymmetry index, and resting and squeeze vectorgrams. In addition data from endoanal ultrasound (EAUS), rectal compliance, measured by threshold rectal volume and maximum rectal volume, and rectal mucosal electrosensitivity studies were included. EAUS was performed using a standard 2D 10 mHz probe (BandK, Denmark). Colonic imaging was also performed where indicated.

Data were assessed using Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA, United States) and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables (sex, number of deliveries, perineal tear, long labour and episiotomy, EAUS findings). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, including demographic data, anorectal physiology studies, time periods and the Rockwood FIQoLS. Kendall tau-c rank correlation coefficient was used to compare SMIS, CCIS and patient satisfaction score. P values of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

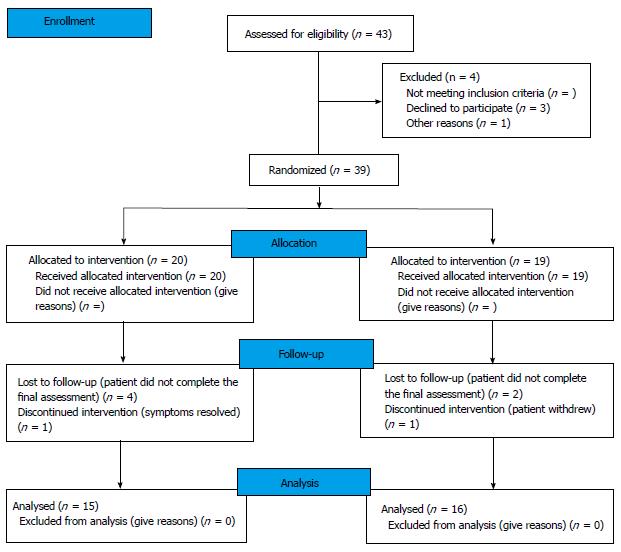

A total of 43 eligible patients invited to participate in this study over a period of 18 mo. Thirty-nine patients, 34 females, consented to participate. Median (IQR) age was 65 (55-75) years. Of those, 20 patients were randomised to the IRAT pathway and 19 patients were randomised to the Standard Care Pathway. Flow diagram of progress through the phases of the study is detailed in Figure 1. The median (IQR) time period from referral by primary care to first clinic appointment in our department was 5 (3-6) wk and 6 (4-8) wk for the Standard Care Pathway and the IRAT pathway respectively. The median (IQR) time period from initiation of management, i.e., first clinic appointment, to competition of management, i.e., discharge back to primary care was 4.5 (4-7) mo and 4 (2-6) mo for the Standard Care Pathway and the IRAT pathway respectively.

One patient withdrew from the IRAT pathway arm of this study because of resolution of her symptoms and declined further assessment. Another patient withdrew from the Standard Care Pathway without stating the reason. Of the initial 39 patients recruited in the study, 31 (79.5%) patients completed their final assessment (part 2.b) and patient satisfaction/feedback (part 2.c) components of the PFAP form. Only data from those 31 patients was included in our analysis (Figure 1).

Demographic data (age, sex, BMI) and medial and obstetric history (history of urinary incontinence, history or symptoms of pelvic floor weakness, history of vaginal delivery, difficult labour, perineal tear and forceps delivery) of those patients are detailed in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

| Pathway | No. of patients | BMI Median (IQR) | Age Median (IQR) | Sex | |

| Standard care pathway | 16 | 26.8 (23.0-31.9) | 70.5 (60.0-76.0) | Female | 14 |

| Male | 2 | ||||

| IRAT | 15 | 27.7 (22.8-35.8) | 66.0 (59.0-77.0) | Female | 12 |

| Male | 3 | ||||

| P value | 0.77 | 0.6 | 0.57 | ||

| Pathway | Vaginal delivery | Difficult labour | Perineal tear | Forceps delivery | Concurrent urinary incontinence | symptoms of global pelvic floor weakness |

| Standard care pathway | 14/14 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 13 | 9 |

| IRAT | 12/14 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 6 |

| P value | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

There was no significant difference in demographic data, obstetric history and anorectal laboratory test results (Table 3) between the two groups of this study.

| Anorectal physiology variables | IRAT pathway Median (IQR) | Standard care pathway Median (IQR) | P value |

| MMRP | 46.0 (36.0-80.0) | 55 (38.5-72) | 0.96 |

| MMSP | 74.0 (57.0-89.0) | 50.0 (37.0-72.0) | 0.88 |

| Resting victor volume | 33308.0 (16559.2-54994.0) | 51224.0 (29444.0-77663.0) | 0.17 |

| Squeeze victor volume | 61168.0 (44393.0-165403.0) | 81303 (51751.0-118808.5) | 0.79 |

| Squeeze asymmetry | 29.7 (11.7-27.1) | 14.4 (8.4-16.9) | 0.07 |

| Resting asymmetry | 20.9 (13.5-31.0) | 17.9 (11.2-27.1) | 0.41 |

| USS-IAS | 2 abnormal | 2 abnormal | 1.00 |

| USS-EAS | 2 abnormal | 1 abnormal | 0.59 |

| Resting vectrogram | 4 abnormal | 5 abnormal | 0.94 |

| Squeeze vectrogram | 3 abnormal | 5 abnormal | 0.43 |

| TRV | 85 (50-100) | 80 (50-95) | 0.85 |

| MRV | 140 (100-195) | 140 (100-195) | 0.94 |

| AME (high) | 6.5 ( 5.2-10.6) | 7.1 (5.5-11.3) | 0.93 |

| AME (mid) | 5.3 (3.6-7.5) | 5.9 (4.6-7.7) | 0.89 |

| AME (low) | 4.7 (2.8-6.6) | 5.1 (3.0-6.5) | 0.85 |

Similarly, there was no significant difference in baseline FIQoLS, SMIS and CCIS between the two study groups (Tables 4 and 5).

| Baseline | FIQoLS 1 Median (IQR) | FIQoLS 2 Median (IQR) | FIQoLS 3 Median (IQR) | FIQoLS 4 Median (IQR) |

| IRAT pathway | 3.6 (2.0.2-4) | 2.7 (1.4-3.4) | 3.7 (2.3-4.1) | 2.7 (1.3-3.8) |

| Standard care pathway | 3.5 (2.3-3.7) | 2.4 (1.6-3.0) | 3.1 (2.0-3.7) | 2.0 (1.3-2.7) |

| P value | 0.44 | 0.94 | 0.11 | 0.22 |

| Baseline | CCIS Median (IQR) | SMIS Median (IQR) |

| IRAT pathway | 8.0 (33.5-11.5) | 13.0 (5.5-13.0) |

| Standard care pathway | 9.5 (5.0-15.0) | 12.0 (7.0-16.0) |

| P value | 0.11 | 0.18 |

Three patients in Standard Care Pathway underwent perianal injection of bulking agent (Permacol®), one of them subsequently referred to SNS in a tertiary care centre due to persistence of symptoms. Another patient in the Standard Care Pathway was referred to the gynaecology team with severe uterine prolapse and subsequently underwent hysterectomy. One patient in the IRAT pathway was referred for SNS a tertiary care centre. The rest of the patients in both study groups were managed conservatively, mainly with pelvic floor exercise and biofeedback. One patient’s symptoms resolved after amending his cholesterol medication.

Final follow-up with FIQoLS, SMIS, CCIS and patient satisfaction score was carried out in a median (IQR) of 1 (1-3) mo after completion of management. This shows no significant difference in any of the four scales of FIQoLS, i.e., the lifestyle, coping, depression and embarrassment scales, between both study groups (Table 6). Similarly there was no difference in CCIS or SMIS at final follow-up (Table 7).

| After completion of management | FIQoLS 1 Median (IQR) | FIQoLS 2 Median (IQR) | FIQoLS 3 Median (IQR) | FIQoLS 4 Median (IQR) |

| IRAT pathway | 3.9 (2.2- 4.0) | 2.9 (1.8 3.8) | 3.9 (2.3-4.1) | 3.0 (1.8-3.8) |

| Standard care pathway | 3.6 (2.4-4.0) | 3.8 (1.7-4.0) | 3.5 (2.1-3.9) | 2.3 (1.6-3.7) |

| P value | 0.51 | 0.92 | 0.18 | 0.87 |

| After completion of management | CCIS Median (IQR) | SMIS Median (IQR) |

| IRAT pathway | 6.0 (1.5 -11.5) | 7.0 (30-15.5) |

| Standard care pathway | 7.5 (3.0-12.0) | 9.5 (4.0-11.0) |

| P value | 0.37 | 0.85 |

Patients’ satisfaction scores in 7 of the 9 item questionnaire were not significantly different (Table 8). However patients in the IRAT pathway were more satisfied with the time required for completion of treatment (form first clinic appointment to discharge) than those in the Standard Care Pathway (P = 0.033). There was also a stronger agreement among the IRAT Pathway group that the questionnaire in the FPAP covered all aspects of their problem (P = 0.006).

| Please rate your degree of satisfaction with each of the following aspect | Standard care pathway median (IQR) | IRAT pathway median (IQR) | P value |

| The waiting time from seeing your GP until been seen at York hospital was acceptable | 4 (3-4) | 4 (4-5) | 0.07 |

| The waiting time from being seen at York Hospital until completing your treatment was acceptable | 4 (3-4) | 4 (4-5) | 0.03 |

| The questions you were asked to complete were relevant to your problem? | 4 (4-4) | 4 (4-5) | 0.24 |

| The questions you were asked to complete were clear and easy to answer? | 4 (4-4) | 4 (4-5) | 0.28 |

| The questions you were asked to complete covered all aspect of your problem? | 4 (3-4) | 4 (4-5) | 0.01 |

| You were supported and given clear advices/instructions throughout management | 4 (4-4) | 4 (4-5) | 0.08 |

| You were given enough time to explain your problem/concerns | 4 (4-4) | 4 (4-5) | 0.08 |

| Your privacy and dignity were respected throughout management | 4 (4-5) | 4 (4-5) | 0.43 |

| The over all quality of care you received was high | 4.5 (4-5) | 4 (4-5) | 0.85 |

The median (IQR) time period from referral by primary care to first clinic appointment was similar at 5 (3-7) wk for the both Standard Care Pathway and the IRAT pathway (P = 0.889). The median (IQR) time period for completion of management was 4.5 (4-7) mo and 4 (2-5) mo for the Standard Care Pathway and the IRAT pathway respectively. This was not significantly different (P = 0.307).

This study shows no significant difference in outcome measures such as FIQoLS, SMIS and CCIS when patients were managed in the IRAT Pathway compared to the Standard Care Pathway. The IRAT Pathway was designed to expedite the management of patients with FI. The IRAT clinic takes place once every 8 wk. During the time periods between first and second and second and third clinic visits, the patient would have completed their assessments and treatment respectively. However, this study shows that there was no significant difference in the waiting time for the first clinic appointment and in the time required for completion of management between the two study groups. This could well be due to the inflexibility of the preconceived timetable in the IRAT Pathway. When patients have asked to postpone or change their clinic dates for various reasons, which occurred in the case of 4 patients in the IRAT Pathway, they had to wait for another 8 wk for the next clinic appointment. The Standard Care Pathway, on the other hand, was more flexible, and since colorectal clinics take place every week, they could accommodate for patients’ cancelations and appointment changes on weekly basis. By the same token, patient factors and preferences may have influenced these time scales. This is reflected in the patient satisfaction questionnaire, where patients in the IRAT pathway were more satisfied with the time required for completion of management, in spite of the lack of significant difference in the time scale itself.

Patients in the IRAT Pathway also had stronger agreement that all aspects of their problem were addressed. This could reflect the structured support and thorough education that patients in this group received along with interaction with pelvic floor and biofeedback therapists both in the clinic and in the laboratory.

Both study groups have rated the overall quality of care equally, which, in addition to a non-significantly different outcome measures (FIQoLS, CCIS and SMIS), means the introduction of the IRAT Pathway did not have a major impact on the quality of patient care.

In spite of the outcome measures of this study, patient satisfaction seemed to increase with the use of the IRAT pathway. This finding is compatible with outcomes of other similar studies. Lawson et al[8] report that patient and parent satisfaction increased because of the promptness of securing discharge prescriptions. Goode[9] discovered that patients who had a care map and a nurse case manager were more satisfied with their care.

There is evidence that pathways are more likely to be effective when applied to conditions and procedures with lower severity/complexity of illness, high volume and higher length of stay[10]. This does not apply to FI which is a multifactorial condition with complex aetiology. In addition the volume of patient referred our department for management of FI was relatively low. The risk of “contamination” of the control sample, i.e., communication between experimental and control professionals, was not considered in this study, especially that some of the Standard Care Clinic were run by the same colorectal consultant conducting the IRAT Clinics. Some or all of these factors could have contributed to the final outcome of this study.

Clinical pathways applied to patients with a cardiovascular disease showed a tendency towards a decreased treatment variation, improved guideline compliance and reduced costs. However, the evidence of the effectiveness of clinical pathways in cardiovascular medicine can not be generalized because of the insufficient number of controlled studies[11]. There was a strong decline in both the average length of stay and its variation after implementation of CP in inguinal hernia repair[3]. Similar finding were observed in knee and hip arthroplasty procedures[12]. However, no significant difference in patient outcomes was seen.

On the other hand, no benefit of using clinical pathway in stoke patients was detected over conventional multidisciplinary care[10,13,14]. Functional recovery was faster and quality of life outcomes better in patients receiving conventional multidisciplinary care. Some studies reported major failures in implementation of clinical pathways for stroke and their implementation was discontinued[3].

Some studies did suggest that the use of clinical pathways had no influence on patient-care outcomes, by the same token they also stated that there was no evidence at all that they had any negative effect[15]. However, no, few, or even negative results after implementing CP hardly ever get published[15].

How health care should respond to clinical pathways that have not been shown to improve care, such as some the pathways for strokes and renal failure[3] is not clear and further research is needed to answer this question[16]. The answer depends on the risks, costs, and opportunity costs of continuing to implement critical pathways or other strategies[16].

It has been assumed that critical pathways are not associated with risk, although there are relatively few studies to support or refute that belief. However, critical pathways might be costly to develop, update, and implement. There may also be opportunity costs of not pursuing other strategies that might more effectively improve quality, reduce costs, and enhance patient safety, since these other strategies must compete for organizational resources[16].

Despite widespread enthusiasm for critical pathways, rigorous evidence to support their benefits in health care is extremely limited. However, understanding what evidence-based information is, and translating this information into practice using reminder systems or other effective implementation strategies, can potentially improve care, reduce costs, and enhance safety[16-20].

Rigorous evaluation of CP and medical management approaches is essential in order to determine the effectiveness of CP in particular area of medical care. Pearson et al[21] reported significant reductions in lengths of stay after implementation of CP for surgical conditions. However, this reduction in LOS was similar to those at health care organizations at which there were no organized CP efforts in place. The CP program was responsible for very modest improvements in patient care, and was probably without a measurable “return on investment.” These results occurred in an organization where the investigators are extremely knowledgeable and experienced in the field of critical pathways[22]. Only after the authors observed declining lengths of stay in organizations without critical pathways did they believe that the reductions at their organization were more likely to be a result of secular trends rather than the critical pathways[16]. In this study we randomised patients between CP and standard care which has given us the advantage to overcome this confounding factor. The findings in this study are, however, consistent with those from Pearson et al[21] study.

Studies should also determine the clinical and financial return on investment of these efforts. Organizations should identify which components of their current clinical quality improvement efforts are effective, and which are not. For strategies that are without measurable benefit, consideration should be given to learning from those experiences and may be redirecting resources to more effective quality improvement strategies[16].

Finally, in spite of the lack of significant difference in outcome measures, the IRAT Pathway has positively influenced patient’s mindset, which was reflected in a higher satisfaction score. This has an important impact on the overall care for patients with problems such as faecal incontinence.

The management of faecal incontinence is widely varied, ranging from conservative management with dietary modification, medications and behavioral interventions to invasive therapy including complex surgery. No previous study has discussed the role of clinical pathway in the management of faecal incontinence.

There is evidence that clinical pathways applied to patients with certain conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, showed a tendency towards a decreased treatment variation, improved guideline compliance and reduced costs. However, this evidence cannot be generalized to other conditions, such as faecal incontinence, because of the insufficient number of controlled studies

This is the first randomized controlled study to evaluate the development and implementation of clinical pathway in the management of patients with faecal incontinence and measure its impact on patients’ care.

This pilot study’s design and findings could be used to determine sample size for a larger randamised controlled study aiming to test the impact of clinical pathway and structured patient support and thorough education on clinical outcome and satisfaction in patients with faecal incontinence.

Critical pathways and process mapping methodology was used in industry, particularly in the field of engineering from as early as the 1950s. In the 1980s, clinicians in the United States began to develop the pathway tools and tried to re-define the delivery of care and attempted to identify measurable outcomes. Developed and used initially for the purpose of cost containment, in the United Kingdom in the late 1980s, the emphasis has been to use clinical pathways as a quality tool.

The study is well designed, the manuscript is well written and new data have been provided.

| 1. | Nyatanga T, Holliman R. Integrated care pathways (ICPs) and infection control. Clinical Governance: An International Journal 2005; 106-117. |

| 2. | Goldszer RC, Rutherford A, Banks P, Zou KH, Curley M, Rossi PB, Kahlert T, Goulart D, Santos K, Gustafson M. Implementing clinical pathways for patients admitted to a medical service: lessons learned. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2004;3:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Panella M, Marchisio S, Di Stanislao F. Reducing clinical variations with clinical pathways: do pathways work? Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:509-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hill M. The development of care management systems to achieve clinical integration. Adv Pract Nurs Q. 1998;4:33-39. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2089] [Cited by in RCA: 2024] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 963] [Cited by in RCA: 1007] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantonis C, Thorson AG, Wexner SD, Bliss D, Lowry AC. Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:9-16; discussion 16-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 866] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lawson MJ, Lapinski BJ, Velasco EC. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy pathway plan of care for the pediatric patient in day surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 1997;12:387-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goode CJ. Impact of a CareMap and case management on patient satisfaction and staff satisfaction, collaboration, and autonomy. Nurs Econ. 1995;13:337-348, 361. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kwan J, Sandercock P. In-hospital care pathways for stroke: a Cochrane systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:587-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Panella M, Marchisio S, Demarchi ML, Manzoli L, Di Stanislao F. Reduced in-hospital mortality for heart failure with clinical pathways: the results of a cluster randomised controlled trial. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:369-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim S, Losina E, Solomon DH, Wright J, Katz JN. Effectiveness of clinical pathways for total knee and total hip arthroplasty: literature review. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:69-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sulch D, Perez I, Melbourn A, Kalra L. Randomized controlled trial of integrated (managed) care pathway for stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2000;31:1929-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kwan J, Sandercock P. In-hospital care pathways for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD002924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Renholm M, Leino-Kilpi H, Suominen T. Critical pathways. A systematic review. J Nurs Adm. 2002;32:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weingarten S. Critical pathways: what do you do when they do not seem to work? Am J Med. 2001;110:224-225. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Weingarten S, Ermann B, Bolus R, Riedinger MS, Rubin H, Green A, Karns K, Ellrodt AG. Early “step-down” transfer of low-risk patients with chest pain. A controlled interventional trial. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:283-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Weingarten S, Agocs L, Tankel N, Sheng A, Ellrodt AG. Reducing lengths of stay for patients hospitalized with chest pain using medical practice guidelines and opinion leaders. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:259-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mugford M, Banfield P, O’Hanlon M. Effects of feedback of information on clinical practice: a review. BMJ. 1991;303:398-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Petersen LA, Teich JM, Burdick E, Hickey M, Kleefield S, Shea B. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA. 1998;280:1311-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1315] [Cited by in RCA: 1210] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pearson SD, Kleefield SF, Soukop JR, Cook EF, Lee TH. Critical pathways intervention to reduce length of hospital stay. Am J Med. 2001;110:175-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pearson SD, Goulart-Fisher D, Lee TH. Critical pathways as a strategy for improving care: problems and potential. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:941-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): B

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Abdel-Salam OME, Duchalais E S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL