Published online Nov 6, 2016. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i4.564

Peer-review started: June 2, 2016

First decision: July 4, 2016

Revised: July 19, 2016

Accepted: September 13, 2016

Article in press: September 15, 2016

Published online: November 6, 2016

Processing time: 151 Days and 14.8 Hours

To evaluate how different levels of adherence to a mediterranean diet (MD) correlate with the onset of functional gastrointestinal disorders.

As many as 1134 subjects (598 M and 536 F; age range 17-83 years) were prospectively investigated in relation to their dietary habits and the presence of functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients with relevant chronic organic disease were excluded from the study. The Mediterranean Diet Quality index for children and adolescents (KIDMED) and the Short Mediterranean Diet Questionnaire were administered. All subjects were grouped into five categories according to their ages: 17-24 years; 25-34; 35-49; 50-64; above 64.

On the basis of the Rome III criteria, our population consisted of 719 (63.4%) individuals who did not meet the criteria for any functional disorder and were classified as controls (CNT), 172 (13.3%) patients meeting criteria for prevalent irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and 243 (23.3%) meeting criteria for prevalent functional dyspepsia (FD). A significantly lower adherence score in IBS (0.57 ± 0.23, P < 0.001) and FD (0.56 ± 0.24, P < 0.05) was found compared to CNT (0.62 ± 0.21). Females with FD and IBS exhibited significantly lower adherence scores (respectively 0.58 ± 0.24, P < 0.05 and 0.56 ± 0.22, P < 0.05) whereas males were significantly lower only for FD (0.53 ± 0.25, P < 0.05). Age cluster analyses showed a significantly lower score in the 17-24 years and 25-34 year categories for FD (17-24 years: 0.44 ± 0.21, P < 0.001; 25-34 years: 0.48 ± 0.22, P < 0.05) and IBS (17-24 years: 0.45 ± 0.20, P < 0.05; 24-34 years: 0.44 ± 0.21, P < 0.001) compared to CNT (17-24 years: 0.56 ± 0.21; 25-34 years: 0.69 ± 0.20).

Low adherence to MD may trigger functional gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly in younger subjects. Moreover, with increasing age, patients tend to adopt dietary regimens closer to MD.

Core tip: Diet seems to be one of the most important triggering factor for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID). In fact, patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia frequently report the onset of symptoms after a meal or the consumption of certain types of foods. The mediterranean (MD) diet is universally considered a health-promoting dietary regimen, since populations adopting this type of diet exhibit a lower rate of major cardiovascular, neoplastic, metabolic morbidity and mortality. Emerging evidence supports a beneficial effect of MD on the gastrointestinal tract, although the association between a high adherence to MD and FGID symptoms is still unclear.

- Citation: Zito FP, Polese B, Vozzella L, Gala A, Genovese D, Verlezza V, Medugno F, Santini A, Barrea L, Cargiolli M, Andreozzi P, Sarnelli G, Cuomo R. Good adherence to mediterranean diet can prevent gastrointestinal symptoms: A survey from Southern Italy. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7(4): 564-571

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v7/i4/564.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i4.564

The Mediterranean diet (MD) is considered as a complex set of eating habits adopted by peoples in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. It includes high consumption of olive oil, fiber-rich foods, milk or dairy products and low consumption of meat or meat-based products[1]. In the last few years, this dietary regimen has been universally proposed as a health-protective diet since populations who have adopted it show a remarkable reduction in all-cause mortality[2], especially from cardiovascular diseases and cancer, compared to the United States or Northern European countries[3]. The beneficial effects of MD may be attributed to the large consumption of antioxidants contained in raw fruit and vegetables or to a reduced consumption of saturated fats.

A healthy diet is also important to preserve gastrointestinal balance. Indeed, some alimentary regimens or even some meals are able to trigger symptoms in individuals with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), such as functional dyspepsia (FD) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). FGIDs are highly prevalent chronic disorders occurring in the absence of any organic etiology[4]. They are often associated with psychological co-morbidities, such as depression or anxiety, which negatively influence the quality of life and cause absence from work or school with a consequently relevant economic burden. The etiology of FGID is thought to be multifactorial, and includes altered brain-gut interactions, genetic predispositions, and/or environmental factors, such as diet[5,6]. Actually, food - especially some types of foods - seems to be the most important triggering factor. Up to 75% of adults with IBS report that diets high in carbohydrates, fatty foods, coffee, alcohol, and hot spices worsen their GI symptoms[7]. Dyspeptic patients usually report that meal size, eating patterns, caloric intake as well as nutrient composition-lipid content in particular-strongly influence the onset of dyspeptic symptoms. Several mechanisms have been hypothesized to account for the association between food and gastrointestinal symptoms, i.e., influence of food on microbiota composition; luminal distension related to gas production from bacterial fermentation; direct effects of some nutrients on GI sensitivity and motility[8,9].

Emerging evidence[4,10] supports the hypothesis that MD may be beneficial also for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Against this background, the aim of our study was to evaluate how different levels of adherence to MD correlate with the onset of functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia.

Our study was performed in Campania, a region of Southern Italy between May 2011 and April 2012. As many as 1134 subjects (598 M and 536 F; age range 17-83 years) without a prior abdominal surgery or relevant organic chronic disease, on the basis of an accurate history taking, were investigated in relation to their dietary habits; of these, 114 were outpatients of the “Federico II” University Hospital (Naples), 401 had been surveyed during an open event for health prevention held in the city of Caserta; 619 were evaluated during a health care program in a secondary school in Naples.

All subjects were administered the Rome III questionnaire to assess the presence of upper or lower gastrointestinal symptoms: 719 patients did not report any relevant gastrointestinal symptoms (controls), 172 met the criteria for prevalent irritable bowel syndrome and 243 for prevalent functional dyspepsia. Controls, IBS and FD patients were classified according to age: 17-24 years old, 25 to 34 years old, 35 to 49 years old, 50 to 64 years old and, finally, above 64 years of age.

In addition, all subjects completed a standardized food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) evaluating their adherence to the Mediterranean Diet model. In order to explore the adherence to MD in different age categories, we used two different questionnaire: The Mediterranean Diet Quality index for children and adolescents (KIDMED) was administered to participants whose ages ranged from 17 to 24 years, and the Short Mediterranean Diet Questionnaire to those older than 24 years. Both questionnaires were developed according to the principles behind Mediterranean dietary patterns.

The KIDMED index is based on a 16-question test with scores ranging from 0 to 12; questions denoting a negative connotation compared to the Mediterranean diet model were assigned a value of -1, those with positive aspects were assigned +1 (Table 1). The score obtained was classified into three levels of adherence to the Mediterranean dietary model: > 8 optimal; 4-7 intermediate, ≤ 3 very low adherence[11,12].

| Scoring | |

| +1 | Has one fruit or fruit juice every day |

| +1 | Has a second fruit every day |

| +1 | Has fresh or cooked vegetables regularly once a day |

| +1 | Has fresh or cooked vegetables more than once a day |

| +1 | Consumes fish regularly (at least 2-3 times per week) |

| -1 | Goes more than once a week to a fast-food (hamburger) restaurant |

| +1 | Likes pulses and eats them more than once a week |

| +1 | Consumes pasta or rice almost every day (5 or more times per week) |

| +1 | Has cereals or grains for breakfast |

| +1 | Consumes nuts regularly (at least 2-3 times per week) |

| +1 | Uses olive oil at home |

| -1 | Skips breakfast |

| +1 | Has a dairy product for breakfast (yoghurt, milk, etc.) |

| -1 | Has commercially baked goods or pastries for breakfast |

| +1 | Has two yoghurt and/or some cheese (40 g) daily |

| -1 | Has sweets and candy several times every day |

The Short Mediterranean Diet Questionnaire derives from a larger validated FFQ including 136 items; it is based on a 9-question test assessing the frequency of consumption for nine typical food categories. A specific frequency score was assigned to each food to attribute +1 only when food consumption satisfied the criteria (Table 2). The final composite score ranged from 0 to 9 and, as for the KIDMED index, it was classified into three levels of adherence to the Mediterranean diet: > 7 optimal; 4-6 intermediate, ≤ 3 very low adherence[13].

| Scoring | |

| +1 | Olive Oil (> 1 spoon/d) |

| +1 | Fruit (≥ 1 serving/d) |

| +1 | Vegetables or Salads (≥ 1 serving/d) |

| +1 | Fruit (≥ 1 serving/d) and vegetable (≥ 1 serving/d) |

| +1 | Legumes (≥ 2 serving/d) |

| +1 | Fish (≥ 3 serving/d) |

| +1 | Wine (≥ 1 glass/d) |

| +1 | Meat ( ≤ 1 serving/d) |

| +1 | White bread ( ≤ 1 serving/d) and rice ( ≤ 1 serving/wk) or whole-grain bread (> 5/wk) |

Since two different types of questionnaires were used, the final index ranged from 0 to 9 or from 0 to 12; for this reason, to equalize the score obtained for each patient, final scores were divided by the maximum result achievable depending on the questionnaire employed.

Data were evaluated using SPSS for Windows version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Results were analyzed using t-test and ANOVA. Differences were considered significant when the P value was below 0.05. A multinomial regression model was used to analyze whether the level of adherence to MD was associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders, age category, sex or BMI. Results are reported as adjusted odds ratio with 95%CI; P-values below 0.05 were considered as significant. The output of the multinomial logistic regression is presented as a set of two dichotomous logistic regressions that provide a pairwise comparison of the phenotypes, as follows: High vs low adherence to MD and high vs intermediate adherence to MD. The oldest group, controls, individuals presenting with third grade obesity, and females were used as reference category in the multinomial regression model.

Overall, 1134 subjects were investigated as to presence of both upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms and were thus classified into the following groups: Controls, functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome. Thereafter, they were all stratified by level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet (low, intermediate and high adherence) and age category (17-24; 25-34; 35-49; 50-65; > 65 years) (Table 3).

| Level of adherence to MD | ||||

| Age category (yr) | Low | Intermediate | High | |

| CNT | 17-24 | 61 (20.5) | 158 (53.0) | 79 (26.5) |

| 25-34 | 11 (11.8) | 55 (59.1) | 27 (29) | |

| 35-49 | 14 (9.9) | 91 (64.5) | 36 (25.5) | |

| 50-65 | 22 (16.4) | 89 (66.4) | 23 (17.2) | |

| > 65 | 3 (5.7) | 37 (69.8) | 13 (21.9) | |

| IBS | 17-24 | 10 (34.5) | 17 (56.8) | 2 (6.9) |

| 25-34 | 6 (25) | 18 (75) | 0 | |

| 35-49 | 13 (28.3) | 27 (58.7) | 6 (13) | |

| 50-65 | 4 (9.8) | 29 (70.7) | 8 (19.5) | |

| > 65 | 5 (15.6) | 20 (62.5) | 7 (21.9) | |

| FD | 17-24 | 38 (39.2) | 43 (44.3) | 16 (16.5) |

| 25-34 | 7 (20.6) | 25 (73.5) | 2 (5.9) | |

| 35-49 | 7 (14) | 34 (68) | 9 (18) | |

| 50-65 | 7 (15.2) | 25 (54.3) | 14 (30.4) | |

| > 65 | 4 (25) | 6 (37.5) | 6 (37.5) | |

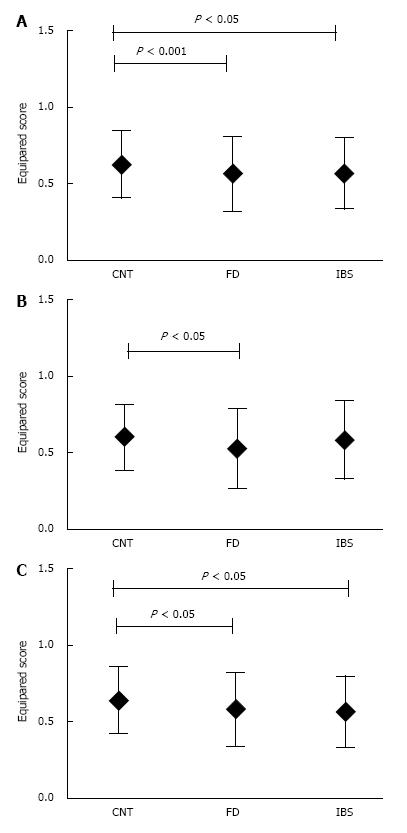

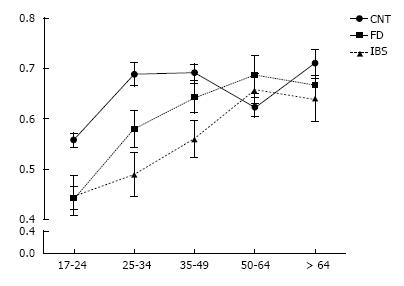

A significantly lower adherence score among FD (0.56 ± 0.24, P < 0.001) and IBS (0.57 ± 0.23, P < 0.05) was found compared to CNT (0.62 ± 0.21) (Figure 1A). When the data were stratified by gender, females with FD and IBS exhibited significantly lower adherence scores (respectively 0.58 ± 0.24, P < 0.05 and 0.56 ± 0.22, P < 0.05) as compared to CNT (0.64 ± 0.22), whereas in males they were significantly lower only for FD (0.53 ± 0.25, P < 0.05) compared to CNT (0.61 ± 0.21) (Figure 1B and C). Age cluster adherence scores were significantly lower in the 17-24 years and 25-34 years categories for FD (17-24 years: 0.44 ± 0.21, P < 0.001; 25-34 years 0.58 ± 0.22, P < 0.05) and IBS (17-24 years: 0.45 ± 0.20, P < 0.05; 25-34 years: 0.49 ± 0.21, P < 0.001) compared to CNT (17-24 years: 0.56 ± 0.21; 25-34 years: 0.69 ± 0.20). In the 35-49 year category, the adherence score was significantly lower only in the IBS group (0.56 ± 0.24, P < 0.001) compared to CNT (0.69 ± 0.19). No differences were observed between the other age clusters (Figure 2). However, when stratified by gender, in the 17-24 year category, a lower adherence score was confirmed for females with FD (0.48 ± 0.22, P < 0.05) and IBS (0.44 ± 0.17, P < 0.05) vs CNT (0.57 ± 0.22), whereas the male group presented a significantly lower adherence score only for FD (0.39 ± 0.19, P < 0.001) compared to CNT (0.55 ± 0.20). At the same time, stratifying the 25-34 year category by gender, only IBS males (0.46 ± 0.20, P < 0.05) and females (0.50 ± 0.21, P < 0.05) had a significantly lower mean adherence score compared to controls (0.70 ± 0.18 and 0.68 ± 0.21). Finally, stratifying other age categories by gender, only IBS females in the 35-49 year group (0.55 ± 0.24, P < 0.05) exhibited a significantly lower mean adherence score compared to controls (0.69 ± 0.19). No differences were observed for other gender groups (Table 4).

| Age range (yr) | Sex | CNT | FD | IBS |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| 17-24 | Tot | 0.56 ± 0.21 | 0.44b± 0.21 | 0.45a± 0.20 |

| M | 0.55 ± 0.20 | 0.39b± 0.19 | 0.46 ± 0.26 | |

| F | 0.57 ± 0.22 | 0.48a± 0.22 | 0.44a± 0.17 | |

| 25-34 | Tot | 0.69 ± 0.20 | 0.58a± 0.22 | 0.49b± 0.21 |

| M | 0.70 ± 0.18 | 0.60 ± 0.24 | 0.46a± 0.20 | |

| F | 0.68 ± 0.21 | 0.56 ± 0.17 | 0.50a± 0.21 | |

| 35-49 | Tot | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.64 ± 0.20 | 0.56 ± 0.24 |

| M | 0.70 ± 0.20 | 0.74 ± 0.15 | 0.65 ± 0.21 | |

| F | 0.69 ± 0.19 | 0.61 ± 0.21 | 0.55a± 0.24 | |

| 50-64 | Tot | 0.62 ± 0.20 | 0.69 ± 0.24 | 0.66 ± 0.18 |

| M | 0.60 ± 0.19 | 0.65 ± 0.21 | 0.75 ± 0.26 | |

| F | 0.63 ± 0.20 | 0.70 ± 0.25 | 0.64 ± 0.19 | |

| > 64 | Tot | 0.71 ± 0.18 | 0.67 ± 0.28 | 0.64 ± 0.24 |

| M | 0.74 ± 0.12 | 0.70 ± 0.32 | 0.69 ± 0.26 | |

| F | 0.69 ± 0.21 | 0.64 ± 0.25 | 0.62 ± 0.23 |

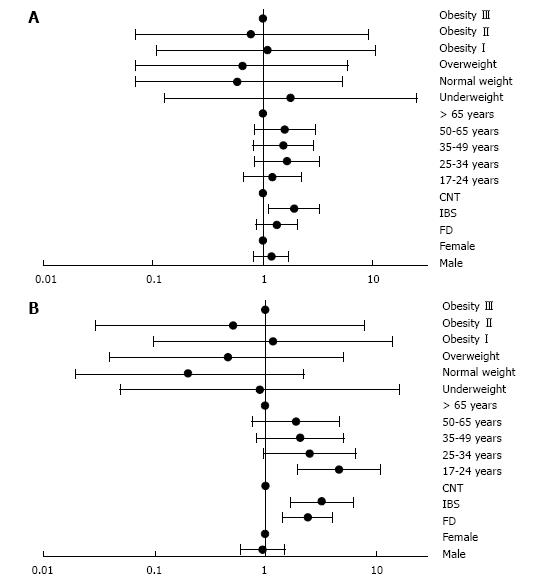

Both low (OR = 3.24, 95%CI: 1.73-6.08, P < 0.0001) and intermediate (OR = 1.91, 95%CI: 1.14-3.22, P < 0.05) levels of adherence to MD were independently associated with the presence of IBS. However only FD (OR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.47-3.99, P < 0.0001) and the youngest age category (OR = 4.65, 95%CI: 2.00-10.81, P < 0.0001) were associated with a low level of adherence to MD (Table 5, Figure 3A and B).

| Low adherence | Intermediate adherence | |||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| FD | 2.42 | 1.47-3.99 | < 0.0001 | 1.34 | 0.88-2.03 | NS |

| IBS | 3.24 | 1.73-6.08 | < 0.0001 | 1.91 | 1.13-3.22 | < 0.05 |

| 17-24 yr | 4.65 | 2.00-10.81 | < 0.0001 | 1.78 | 0.13-24.96 | NS |

The present study provides evidence that the MD adherence score is significantly lower in subjects with GI symptoms than in asymptomatic subjects, showing an inverse relationship between adherence to MD and prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms. Moreover, among FGID subjects, only younger age categories (17-24 and 25-34 years.) were associated with lower adherence to MD compared to controls, whereas for older people, no differences were observed between symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects.

Many factors, such as age, gender, nationality, socio-economic condition, may influence dietary adherence to MD[14]. Our results confirm the data from several studies exploring dietary habits in different European countries, widely demonstrating that young people exhibit the lowest level of adherence to MD[12,15,16]. In Italy, a lower adherence to MD has also been confirmed among young people, particularly for those coming from northern region. As shown by Noale et al[17] of the Italian adolescents examined in their study, only 14% exhibited a high adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and 47% a moderate adherence. In fact, not only did the mean daily caloric intake exceed the dietary requirements recommended by “Nutrient Intake Goal for the Italian population” or LARN tables, but they also observed an increase in the intake of saturated fats and proteins as compared to carbohydrates, fruit or vegetables. This may be a consequence of the frequent use of easy-to-prepare and ready-to-use products or fast foods, which are characterized by a lower nutritional quality due to the addition of sugar and saturated fats[18].

Unbalanced diets adopted by young people may contribute to the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients suffering from functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome[6,8]. Patients with FGID exhibit gastro-intestinal hypersensitivity and exaggerated reflex after ingestion of lipids. Moreover, fats influence gastric activity, by delaying gastric emptying and promoting relaxation of the fundus in healthy subjects as well as in dyspeptic patients[7,19,20]. However, fundus relaxation appears impaired in functional dyspepsia since, following lipid infusion, the discomfort threshold observed in FD patients appears to be lower than in controls[21]. In clinical practice, all these disturbances following lipid intake occur much more frequently in dyspeptic patients than in healthy individuals.

Similarly to FD, patients with IBS report abdominal bloating following the intake of foods rich in fatty acids. Fatty meals are also able to alter intestinal motility, increasing whole intestinal transit time and, in some cases, inducing a reflex stimulation of colonic motor activity (gastrocolonic reflex) which may explain the post-prandial defecation observed in IBS-D patients[7].

On the basis of such evidence, it has been hypothesized that since the Mediterranean diet is based only minimally on foods or eating habits able to trigger gastrointestinal symptoms, it represents a therapeutic dietary regimen for FGID patients. Indeed, MD is a restricted-calorie dietary model with fats providing less than 35% of total calories[2,22,23]. In addition, MD is characterized by small meals that may exert beneficial effects in both FD patients - by favoring easy gastric emptying, and in IBS-D patients - since it stimulates impaired gastro-colonic reflex only to a limited extent[4,7]. The use of olive oil, as main source of fatty acids, largely preferred to meat and meat-based foods, provides a high intake of mono-unsaturated and omega-3 fatty acids, which may alter gastric emptying less than saturated fats. At the same time, several studies have shown that these kinds of fatty acids may even reduce the microscopic inflammation of colonic mucosa occurring in IBS patients, providing long-term beneficial effects[24].

Noteworthy, our study has shown that subjects in older age categories show greater adherence to MD but nonetheless have persistent functional gastrointestinal symptoms; several factors have been taken into account to explain such evidence. Ageing is characterized by cellular senescence - with consequent reduction in cellular proliferation capability, enteric neuronal loss and low-grade systemic inflammation status called “inflammaging”. Consequently, ageing itself may strongly influence gastrointestinal motility, sensitivity, nutrient absorption or gut microbiota composition. Moreover, the presence of several co-morbidities, both mild or severe, is associated with an increased use of medications that deeply influence gastrointestinal activity and its environment (pH, temperature or motility), with secondary effects on bacterial colonization[25,26]. Several research studies have shown that, in the elderly, the stability and variety of microbiota tend to diminish[27]. In fact, there is evidence that Bacteroides and Bifidobacteria become less abundant, mylolytic activity and the availability of short chain fatty acid (SCFA) decrease, with a concomitant increase in the presence of facultative anaerobes, fusobacteria and clostridia[28]. For these reasons, differently from younger individuals, many factors other than diet predispose elderly people to the onset of gastrointestinal problems, which explains the persistence of GI symptoms despite a higher adherence to MD.

The use of questionnaire, both KIDMED and Short Mediterranean one, to evaluate the adherence to a specific diet needs caution because a short score focuses just to a few foods, representative for that alimentary behavior, instead of the whole diet. Moreover, it would be very useful to expand the dietary analysis considering even the amount of food intake in order to evaluate the calories consumed in association with the adherence to MD. This study was performed on subjects living in the same region, therefore, since MD is a dietary regimen which involves several populations, a multicenter prospective study would clarify better the beneficial effect of this diet on functional gastrointestinal symptoms.

In conclusion, the association between food intake and FGID seems to be very complex since each food item may exert a specific effect on the gastrointestinal tract. As several studies have reported that food intake is associated with the onset of symptoms in these disorders, dietary intervention is strongly recommended in the management of FGID. Nutritional therapeutic measures may include different aspects of food intake such as meal size, caloric intake as well as nutrient composition or even meal viscosity. A wide range of dietary regimens, including the Mediterranean Diet, have been proposed for FGID, however the efficacy of such “therapeutic diets” on gastrointestinal symptoms needs further evaluation.

The mediterranean diet (MD) is universally considered as a health protecting dietary regimen since people who adopt it exhibit a lower incidence of cardiovascular, metabolic and neoplastic disease. However, this dietary pattern may have beneficial effects even on gastrointestinal functional disorders, such as functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome.

As the beneficial effects of the MD are widely accepted, the author’s aim is to evaluate how different levels of adherence to this type of dietary regimen may influence the onset of functional gastrointestinal symptoms.

The data show that low adherence to MD may trigger functional gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly in younger subjects. Moreover, with increasing age, patients attribute greater importance to their diet and, for this reason, tend to adopt eating habits closer to MD.

Dietary interventions are fundamental for a correct therapeutic approach of functional gastro-intestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia. The data support the notion that the adoption of a diet very close to MD - instead of extremely restricted dietary regimens, should be proposed in individuals presenting these disorders.

The topic was interesting and this study was well conducted. The results could help to identify a new dietary habit to prevent gastrointestinal disorders.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Italy

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): C, C

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chiang TA, Sun XT, Tantau A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Trichopoulou A, Martínez-González MA, Tong TY, Forouhi NG, Khandelwal S, Prabhakaran D, Mozaffarian D, de Lorgeril M. Definitions and potential health benefits of the Mediterranean diet: views from experts around the world. BMC Med. 2014;12:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Castro-Quezada I, Román-Viñas B, Serra-Majem L. The Mediterranean diet and nutritional adequacy: a review. Nutrients. 2014;6:231-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lopez-Garcia E, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Li TY, Fung TT, Li S, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB. The Mediterranean-style dietary pattern and mortality among men and women with cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Azpiroz F, Hernandez C, Guyonnet D, Accarino A, Santos J, Malagelada JR, Guarner F. Effect of a low-flatulogenic diet in patients with flatulence and functional digestive symptoms. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:779-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vanuytsel T, Tack JF, Boeckxstaens GE. Treatment of abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1193-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tack J, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia--symptoms, definitions and validity of the Rome III criteria. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:134-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Food choice as a key management strategy for functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:657-666; quiz 667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Feinle-Bisset C, Azpiroz F. Dietary and lifestyle factors in functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:150-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lacy BE, Talley NJ, Locke GR, Bouras EP, DiBaise JK, El-Serag HB, Abraham BP, Howden CW, Moayyedi P, Prather C. Review article: current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67-75.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 810] [Cited by in RCA: 855] [Article Influence: 71.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Sahingoz SA, Sanlier N. Compliance with Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (KIDMED) and nutrition knowledge levels in adolescents. A case study from Turkey. Appetite. 2011;57:272-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Antonogeorgos G, Panagiotakos DB, Grigoropoulou D, Papadimitriou A, Anthracopoulos M, Nicolaidou P, Priftis KN. The mediating effect of parents’ educational status on the association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and childhood obesity: the PANACEA study. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Martínez-González MA, Fernández-Jarne E, Serrano-Martínez M, Wright M, Gomez-Gracia E. Development of a short dietary intake questionnaire for the quantitative estimation of adherence to a cardioprotective Mediterranean diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1550-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arriscado D, Muros JJ, Zabala M, Dalmau JM. Factors associated with low adherence to a Mediterranean diet in healthy children in northern Spain. Appetite. 2014;80:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tognon G, Moreno LA, Mouratidou T, Veidebaum T, Molnár D, Russo P, Siani A, Akhandaf Y, Krogh V, Tornaritis M. Adherence to a Mediterranean-like dietary pattern in children from eight European countries. The IDEFICS study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38 Suppl 2:S108-S114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Santomauro F, Lorini C, Tanini T, Indiani L, Lastrucci V, Comodo N, Bonaccorsi G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet in a sample of Tuscan adolescents. Nutrition. 2014;30:1379-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Noale M, Nardi M, Limongi F, Siviero P, Caregaro L, Crepaldi G, Maggi S. Adolescents in southern regions of Italy adhere to the Mediterranean diet more than those in the northern regions. Nutr Res. 2014;34:771-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Serra-Majem L, Ribas L, García A, Pérez-Rodrigo C, Aranceta J. Nutrient adequacy and Mediterranean Diet in Spanish school children and adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57 Suppl 1:S35-S39. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Tack J, Caenepeel P, Piessevaux H, Cuomo R, Janssens J. Assessment of meal induced gastric accommodation by a satiety drinking test in health and in severe functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2003;52:1271-1277. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Cuomo R, Vandaele P, Coulie B, Peeters T, Depoortere I, Janssens J, Tack J. Influence of motilin on gastric fundus tone and on meal-induced satiety in man: role of cholinergic pathways. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:804-811. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Feinle C, Meier O, Otto B, D’Amato M, Fried M. Role of duodenal lipid and cholecystokinin A receptors in the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2001;48:347-355. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sirtori CR, Tremoli E, Gatti E, Montanari G, Sirtori M, Colli S, Gianfranceschi G, Maderna P, Dentone CZ, Testolin G. Controlled evaluation of fat intake in the Mediterranean diet: comparative activities of olive oil and corn oil on plasma lipids and platelets in high-risk patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;44:635-642. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Shai I, Spence JD, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Parraga G, Rudich A, Fenster A, Mallett C, Liel-Cohen N, Tirosh A. Dietary intervention to reverse carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2010;121:1200-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Santoro A, Pini E, Scurti M, Palmas G, Berendsen A, Brzozowska A, Pietruszka B, Szczecinska A, Cano N, Meunier N. Combating inflammaging through a Mediterranean whole diet approach: the NU-AGE project’s conceptual framework and design. Mech Ageing Dev. 2014;136-137:3-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Biagi E, Nylund L, Candela M, Ostan R, Bucci L, Pini E, Nikkïla J, Monti D, Satokari R, Franceschi C. Through ageing, and beyond: gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 778] [Cited by in RCA: 978] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Saffrey MJ. Cellular changes in the enteric nervous system during ageing. Dev Biol. 2013;382:344-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O’Connor EM, Cusack S, Harris HM, Coakley M, Lakshminarayanan B, O’Sullivan O. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012;488:178-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1993] [Cited by in RCA: 2380] [Article Influence: 170.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Del Chierico F, Vernocchi P, Dallapiccola B, Putignani L. Mediterranean diet and health: food effects on gut microbiota and disease control. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:11678-11699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |